Erin M.

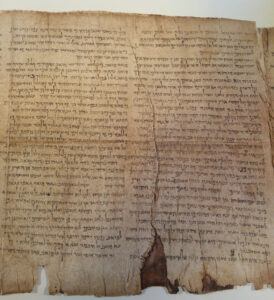

Image of the “Great Isaiah Scroll” a parchment document dated to approximately between 356-100 B.C.E. CC0 Jb344tul at English Wikipedia.

While preparing this article, I was dismayed to look around my study space and see bits of wasted loose-leaf strewn around. If my research on the topic of parchment has taught me anything, it is that writing materials have not always been so expendable. Before the widespread use of paper, parchment was a preferred material for the use of writing. In broad terms, parchment refers to a specially prepared animal skin which is used as a support for writing, printing and even painting. The earliest accounts of animal skin being utilized as a writing base date as far back as the Egyptian fourth dynasty (2550–2450 BC). Assyrian and Babylonian writing from the sixth century B.C.E. onward, as well as many early Islamic and Jewish texts, also used leather as a medium (Norman). While it is difficult to pinpoint when leather was first used as a writing material, the creation of processed parchment is often attributed to the Hellenistic period. One theory is that parchment was “developed under the patronage of Eumenes of Pergamum, as a substitute for papyrus, which was temporarily not being exported from Alexandria, its only source” (Norman). While it is doubtful that parchment was actually “invented” under Eumenes, he likely had a hand in introducing it to the Greek world (Johnson 118). The modern word “parchment” even derives from the Latin “pergamenum,” after the city in which Eumenes streamlined the process of making it.

Unlike my disposable and underappreciated loose-leaf, parchment is a precious commodity which requires time, patience and a skilled craftsperson to create. First, the “parchmenter” would need to select a suitable, preferably blemish-free pelt (Baranov). According to one article, “in the Middle Ages, calfskin and split sheepskin were the most common materials for making parchment in England and France, while goatskin was more common in Italy” (Norman). Pelts from small rodents, as well as larger animals like horses, were also utilized by parchment makers. However, as noted in Hagadorn’s article, by the eighteenth century most documents pertaining to the creation of parchment were “primarily concerned with the working of sheep skins” (170). Vellum, a particularly fine quality parchment, was made from calfskin or the skin of young goats. Even though in modern terminology vellum and parchment are often used interchangeably, historically the former refers to a specific type of parchment. In addition to selecting the species of animal, the parchmenter would also have to consider the animal’s colouring. For example, “white sheep or cows [tended] to produce white parchment” whereas “the shadowy brown patterns which are one of the aesthetically pleasing features of parchment may often be echoes of brindled cows or piebald goats” (Baranov).

Image of “A Skin of parchment stretched on a frame” courtesy of Michele Brown, Cornell University Library Conservation

Once the pelt has been selected, the hard work of transforming a rough animal skin into a clean, thin leaf of parchment begins. While methods may vary, the basic process of creating parchment generally remains the same. The typical steps include “flaying the skin from the carcass, probably preserving it until it can be delivered to the workshop and processing can begin; washing to remove blood and filth; removing components not necessary to processing; drying under tension; and preparing the skin as a surface for writing or other works of art” (Hagadorn 169). After being flayed and cleaned the hair is removed from the skin by soaking it in a special solution. Originally, the dehairing liquors were “made of rotted, or fermented, vegetable matter, like beer or other liquors, but by the Middle Ages an unhairing bath included lime” (Norman). After soaking for around three to ten days, the pelts are removed and scraped of excess hair with a special curved knife called a “lunellarium,” a tool known to have been used as early as the thirteenth century (Thompson 115). After dehairing, the hide is put through the process of tensioning. The skin is attached to a wooden frame and stretched across which “reorganizes the dermal fibre” and results in the pelt fluid drying “to a hard glue-like consistency” (Hagadorn 178). The skin is then shaved down with a sharp knife to create a thinner surface. Finally, the surface of the skin may be prepared for writing by being smoothed with pumice, dusted with chalk to reduce grease, and even powdered with lime or egg whites to improve colour and texture (Norman). Naturally, after reading about such a fascinating creation process, I was curious to see what parchment creation actually looked like. If you are interested in seeing the process, the following is a link to the BBC video titled “How Parchment is Made”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2-SpLPFaRd0

Considering the volume of work and resources that goes into creating parchment, I wanted to discover what benefits it has as a writing support. In its earliest form, parchment provided an advantage over papyrus as it was more durable and animals like cattle and sheep, unlike the papyrus plant, could survive in most regions (Bernhardt). In addition, in dry climates, parchment can be extraordinarily preserved, as demonstrated by “The Dead Sea Scrolls,” documents which can date back as early as 960 -586 B.C.E. While the use of parchment declined in the later Middle Ages with the advent of paper, it has not disappeared entirely. According to one article, “The heyday of parchment use was during the medieval period, but there has been a growing revival of its use among contemporary artists since the late 20th century” due to the skin’s tendency to raise slightly in response to paint media (Norman). In addition, “parchment is often the material of choice for important documents such as religious texts, public laws, indentures, and land records as it has always been considered a strong and stable material” (Differences).

Studying the long history of parchment and the amount of effort put into producing it has only added to my appreciation of historical texts. Documents made from parchment are not just fascinating for the text they contain, but also for the effort and craftmanship that went into creating the parchment itself.

Works Cited and Consulted

Baranov, Vladimir. “Materials and Techniques of Manuscript Production.” Medieval Manuscript Manual, Central European University, Budapest, http://web.ceu.hu/medstud/manual/MMM/about.html, Accessed 9 Oct. 2018.

Baxter, Stephen. “How parchment is made – Domesday – BBC Two.” YouTube, uploaded by BBC, 2 Aug. 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2-SpLPFaRd0

Bernhardt, Theodore. “Leather, Parchment and Vellum.” The Papyri Pages, 2001-2003, http://papyri.tripod.com/vellum/vellum.html

Brown, Michele, “A skin of parchment stretched on a frame.” Cornell University Library Conservation, April 3, 2015, https://blogs.cornell.edu/culconservation/2015/04/03/parchment-making/

“Differences between Parchment, Vellum and Paper.” U. S. National Archives, August 15, 2016, Accessed 9 Oct. 2018, https://www.archives.gov/preservation/formats/paper-vellum.html

Hagadorn, Alexis. “Parchment Making in Eighteenth-Century France: Historical Practices and the Written Record.” Journal of the Institute of Conservation, 35:2 ,2012, pp 165–188

Halevi, Shai. “Plate 981, Frag 2.” The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library, https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/explore-the-archive/image/B-314643

“Isaiah Scroll.” Wikipedia: The free Encyclopedia, September 14, 2018, Accessed 16 Oct. 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaiah_Scroll

Johnson, Richard R. “Ancient and Medieval Accounts of the “Invention” of Parchment.” California Studies in Classical Antiquity Vol. 3 (1970), pp. 115-122

Norman, Richard. “The History of Vellum and Parchment.” Eden Workshops: A Bookbinders Resource, July 12, 2017, https://www.abaa.org/blog/post/the-history-of-vellum-and-parchment

Thompson, Daniel V. “Medieval Parchment Making.” The Library, Vol. 4, 1935,pp 113-117