Marie C.

Who Needs Catalogues?

To me, libraries are the stuff of dreams. Room after room filled with shelf upon shelf upon shelf of books, journals, newspapers, and other publications on every topic imaginable. All of them there at my fingertips, completely accessible and just waiting to be read. A library like the British Library has a collection of over 150 million items, which cover over 625 km of shelves (About Us). This is a staggering wealth of information, and I’m almost drooling just thinking about it! But such amazing, massive collections of books and other materials can also become the stuff of nightmares… What if you can’t find a book? Or worse, what if you have so many books that you no longer have any concept of what you have and where you’ve stored it?

This is why library catalogues are crucial. Cataloguing systems in their various iterations have been around for as long as libraries, in forms that were often “strictly inventories of property” (Rouse & Rouse 236) rather than their more modern form, which “had a principal function to enable one to locate a book” (236), and which now also contain other useful bibliographic information which allows readers to identify and locate books and other resources based on the subjects that they contain. For this post, I am going to limit my discussion to what OCLC cites as “the most widely used classification system in the world”: the Dewey Decimal system.

Melvil Dewey

Public domain – Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Life and Legacy of Melvil Dewey

Born Melville Louis Kossuth Dewey, the man we now know as Melvil Dewey was a man obsessed with the metric system, captivated by the decimal, and an ardent supporter of a simplified spelling reform, having changed his own name from Melville to Melvil and briefly going by Dui rather than Dewey (How One Library Pioneer). He helped found the first permanent organization of librarians in 1876: the American Library Association (Lerner 173). At this point in time, multiple different classification systems were in use in libraries around the world, but classification and the role of the librarian had not yet developed the scientific approach with which we are now familiar. At the same time as the American Library Association was founded, Melvil also founded two other organizations: the American Metric Bureau and the Spelling Reform Association (Lerner 173). Evidently, his Metric Bureau did not have the desired effect on the American measurement system, however he did manage to impose his spelling simplification system on the Lake Placid Club, a “cooperative resort in the Adirondacks that he established in 1895” (Kendall 52). Dewey’s Wikipedia page provides some amusing results of his “simplr spelin”, citing the menu at the “Adirondak Loj”, which offers entrées featuring “Hadok … Masht potato, Butr, Steamd rys, Letis”, with “Ys cream” for dessert.

Dewey developed his classification system while attending Amherst College, and it was part of the discussion at the first meeting of the Library Association in 1876 (Lerner 174). He subsequently was appointed chief librarian of New York City’s Columbia College and began teaching classes on librarianship in 1887, part of a rising trend in providing specific education for librarians (Lerner 175). He was a prominent member of the library community throughout his career, acting as director of New York State Library from 1889 to 1906, founding a company called Library Bureau which stocked supplies for libraries, and also co-founding and editing Library Journal (How One library Pioneer).

Melvil Dewey is now considered the “Father of Modern Librarianship” (How One Library Pioneer), however, he was also a controversial figure. Assumed to have had Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder, he struggled to get along with others and “was a master at launching and beefing up organizations, but … often had difficulty running them” (Kendall 53). Although Dewey “came up with numerous innovations… he also managed to alienate many colleagues with his unpredictable and demanding behavior” (54). In 1905, he was forced to resign as New York State Librarian after a petition signed by a number of prominent individuals was circulated, a petition criticizing the explicit anti-Semitism evident in circulars issued by Dewey’s Lake Placid Club and its exclusion of Jewish people from its membership (Wiegand 361). He was also known to be a womanizer and worse. Although few women made formal complaints over the years, finally “four prominent librarians” (Kendall 54) made his unwelcome attention known to Association officials. This resulted in his exclusion from the Association and his withdrawal from the library world.

How Does Dewey’s System Work?

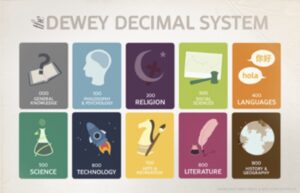

The Dewey Decimal Classification system, abbreviated hereafter as the ‘DDC’, uses arabic decimal numerals and organizes materials based on “ten main classes” which represent fields of study and disciplines intended to “cover the entire world of knowledge” (DDC Summaries). Each of these classes is subdivided into ten divisions, each of which contain ten sections. In this classification, each item in a collection is assigned a three-digit number in which the first digit represents the main class, the second represents the subdivision, and the third represents the section within the division. The three-digit number is followed by a decimal point, after which there are continued degrees of classification, still organized in divisions by ten. Specific subjects may fall under more than one division category, depending on contexts and uses. Thus far, the DDC has been edited 23 times as more topics are assigned numbers and added to the system, and it now also exists as an online resource (DDC Summaries).

Courtesy of Maggie Appleton

Currently, Melvil Dewey’s classification system is used primarily for many smaller collections and public libraries throughout the world, while larger and more academic collections often make use of Herbert Putnam’s Library of Congress classification, which was influenced by Dewey’s work. Despite the definite dark side to the man credited with such innovation, there is no doubt that the library we know and love would not be the same without his contributions.

Works Cited

“About Us.” The British Library. n.d. British Library. Web. 30 Oct. 2018.

“Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) Summaries.” Dewey Services. OCLC. 2018. Web. 2 Nov. 2018.

“History.” American Library Association. ALA. June 9, 2008. Web. 4 Nov. 2018.

“How One Library Pioneer Profoundly Influenced Modern Librarianship.” Dewey Services. OCLC. 2018. Web. 2 Nov. 2018.

Kendall, Joshua. “Melvil Dewey, Compulsive Innovator: The Decimal Obsessions of an Information Organizer.” American Libraries 45.3-4 (2014): 52-54. JSTOR. Web. 1 Nov. 2018.

Lerner, Frederick Andrew. The Story of Libraries: From the Invention of Writing to the Computer Age. 2nd ed. New York: Continuum, 2009. Print.

“Melvil Dewey.” Wikipedia. The Wikimedia Foundation. 28 Oct. 2018. Web. 1 Nov. 2018.

Rouse, Mary A. and Richard H. Rouse. “The Development of Research Tools in the Thirteenth Century.” Authentic Witnesses. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991, 221-255. Print.

Wiegand, Wayne A. “‘Jew Attack’: The Story behind Melvil Dewey’s Resignation as New York State Librarian in 1905.” American Jewish History, vol. 83, no. 3. (1995): 359 379. JSTOR. 1 Nov. 2018.