Nial Willems

Whether one was a precocious child, a naughty grown-up with a taste for the scandalous, or some other wretched creature trapped in between, one’s experience with literature during the 16th through 19th centuries in Britain was likely to be well informed by the popular formats known as broadsides and chapbooks. Thought by some to be derived from the word “cheap”, “chap”-books and the similar single-sided, single-page publications known as broadsides, from which chapbooks developed, were widely distributed and immensely popular forms of literary ephemera during the pre-industrialized printing era (“Broadsides and Chapbooks”). Largely comparable to modern-day newspapers, tabloids and billboards in function, the formats assumed by chapbooks and broadsides are similarly indicative of the time and cultural context in which they arose, being highly adaptable for the conveyance of both the informational and the entertaining.

As a collective format, broadsides and chapbooks are significant for the historical context they help to illuminate about their time of prominence (Morrison). Between detailing crime convictions, announcing public executions, soapboxing on the daftness of vaccination, and making accessible to lower-class citizenry renowned works of song and literature, this kind of cheap literature proved critical to the encoding and dissemination of then-contemporary British culture (Archer).

In one broadside titled “Are You Vaccinated” and originally published by H. Disley, smallpox vaccination—a relatively new medical practice for the day (“Jenner, Edward”)—is given the satirical treatment by a lengthy tongue-in-cheek ballad. Of the 76 lines in this work, 48 are dedicated to providing the reader a comprehensive insight about just who—and what—was at risk of vaccination; citing Napoleon, “the monument on Fish Street Hill”, and even “the devil himself”, the composer frames the fad as all-consuming and utterly inescapable. Furthermore, he comments that vaccination has “turned his wife’s brain” so that she behaves like a monkey and “brays just like a donkey”, playing on the common fear of vaccines as unproven and dangerous. Following this charitable characterization, the writer offers in jest a final challenge for the reader to seek vaccination. While it certainly makes for a fun read today, the flippant sense of humour present in this broadside is also emblematic of a popular style used in early print ephemera which made broadsheets and chapbooks suitable as commercial formats for both packaging cheap laughs and promulgating ideas.

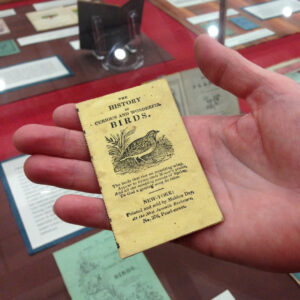

Scale of a typical chapbook compared to a human hand. Image source: http://news.library.mcgill.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/history-of-birds.jpg

Key to the success of this cheap literature was—no doubt—its cheapness, which made it accessible to a far broader cross-section of the British population than the standard full-size book (dschapman). Cost-effectiveness was achieved through the use of low-quality paper, simple but enticing (though not always relevant) woodcut images, a general absence of extraneous decoration, and cheap labour—provided primarily by women and children, or subcontracted to lower class-families for domestic production (Richardson). The simplicity afforded by only imposing onto a single page further economized mass-production. Moreover, early chapbooks were often sold directly to consumers as single, folded sheets, with the trimming and sewing tasks left to the purchaser, should it have been desired (dschapman). Once folded thrice, the typical octavo chapbook contained 16 pages and featured dimensions of approximately 6” x 4” (Richardson), while broadsides “ranged from approximately 13″ x 16″ (‘foolscap’size) to over 5 feet in length” (Gartrell). The minimal use of material and the resulting compact scale of both formats lent them well to the task of economically mass-publicizing individual events, decrees, short-form literature, and, especially, tales of scandal—whether invented, true or a combination of both (dschapman).

In “Murder of Maria Cluasen,” a broadside ballad originally published by W.S. Forntey, the report of Maria Cluasen’s murder is given in ballad form, elevating an already spicy news report to the level of a sensational piece of gruesome literature. According to the broadside, Maria was a servant girl to a certain Mr. Pooks of Greenwich, to whose son she was pledged. Tragically, the dream of their ultimate romance was ended one night when Maria’s betrothed ended her, allegedly on account of her being more handsome than he. Found the next morning a wretched and disfigured mess by the work of a plasterer’s hammer (“Chambers’s Journal”, 266), still clutching to her last breath, she only asked for the release of death. The archetypal image of innocence and purity, the victim of jealous love, poor Ms. Cluasen would not tell the name of her assailant, but died as a piece of poetic tragedy. The prevalent adaptation of stories like Maria Cluasen’s to the broadside ballad format is indicative of several trends in ephemeral literature: firstly, that shocking stories and headlines containing trigger words like “MURDER” tended to be (and still are) big sellers; secondly, that literary formats—like the ballad—were immensely popular for presenting all natures of information in early-modern Britain, even if it did involve some degree of embellishment to make the story fit the form. By contrast, if the story of Maria Cluasen’s murder were to be publicized today, it would almost certainly not be given the same poeticization.

The ability of printers to package and commercialize desirable tidbits of racy content at a tempting price point was just as contributive to the success of early print ephemera as its capacity to connect rural and lower-class communities to a culture and body of literature previously accessible only by the elites. The travelling merchants of chapbooks, known as chapmen, were instrumental in this capacity, fueling the widespread popularity of ephemeral literature all across Britain (Richardson). In addition to chapbooks, chapmen also sold to smaller communities practical, highly sought-after goods—like needles—as well as luxury items principally sold in urban centres (Richardson).

In order to appeal to more affluent audiences, some chapbooks were sold with vibrant paper covers and coloured illustrations; even so, the format was widely regarded by book collectors as amateurish and disposable (Richardson). Still, one can’t help but wonder for how many self-professed book connoisseurs chapbooks of a certain content were a guilty pleasure; for it has not often been the case throughout history that an abundance of wealth has helped to curb the indulgence of vice.

Designed not for love but for money, chapbooks and broadsides might be viewed cynically as the precursors to modern-day mass media that are intended to shock, glorify and reap a mighty profit. Although the impact of print ephemera has contributed toward many noble outcomes, such as helping to increase exposure to literature among the poor, its popularity has also shown how easily people can be taken by showy appearances and stories of devastation. Whether one chooses to moralize the issue or not, however, it seems evident that the commercial success of chapbooks, broadsides and their successors is derived from the ability to entice and tempt; as publishers in the 16th century discovered, cheap thrills can be a lucrative business model.

Works Cited:

“A Brief History of Broadsides.” Tavistock Books, 29 May 2013, http://blog.tavbooks.com/?p=212. Accessed 2 January 2019.

Archer, Caroline. “Chapbooks.” Printweek, 7 August 2013.

“Broadsides and Chapbooks.” The Scottish Archive Network, 2000, http://www.scan.org.uk/knowledgebase/topics/broadsides_topic.htm. Accessed 1 January 2019.

“Chambers’s Journal.” Chambers’s Journal of Popular Literature, Science and Art, 25 April 1885.

Disley, H. “Are You Vaccinated” Michael Sadleir Collection of Ephemera, http://www.londonlowlife.amdigital.co.uk/Contents/ImageViewerPage.aspx?imageid=65487&pi=1&prevpos=16260&vpath=contents. Accessed 2 January 2019. Broadside ballad.

dschapman. “A Brief History of Chapbooks.” Antique Book Collecting, 7 April 2013, https://bookcollecting.wordpress.com/2013/04/07/a-brief-history-of-chapbooks/. Accessed 2 January 2019.

Fortney, W.S. “Murder. Maria Cluasen sic.” Michael Sadleir Collection of Ephemera. http://www.londonlowlife.amdigital.co.uk/Search/DocumentDetailsSearch.aspx?documentid=18455&prevPos=18455&dt=01180744329153918&previous=3&vpath=SearchResults&pi=1. Accessed 4 January 2019. Broadside ballad.

Gartrell, Ellen. “More About Broadsides and the Broadsides Collection.” Duke University Libraries Digital Collections, n.d., https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/eaa/guide/broadsides/. Accessed 9 January 2019.

“Jenner, Edward.” Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, n.d., https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/heritage/art/jenner-edward-1749-1823. Accessed 15 January 2019.

Morrison, Brooke. “What Are Broadsides?” Biblio.com, https://www.biblio.com/book-collecting/what-to-collect/poetry/what-are-broadsides/. Accessed 2 January 2019.

Ramundo, Merika. “history-of-birds.” 2014, http://news.library.mcgill.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/history-of-birds.jpg. JPG file.

Richardson, Ruth. “Chapbooks.” British Library, 15 May 2014, https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/chapbooks. Accessed 1 January, 2019.