Michelle Kent

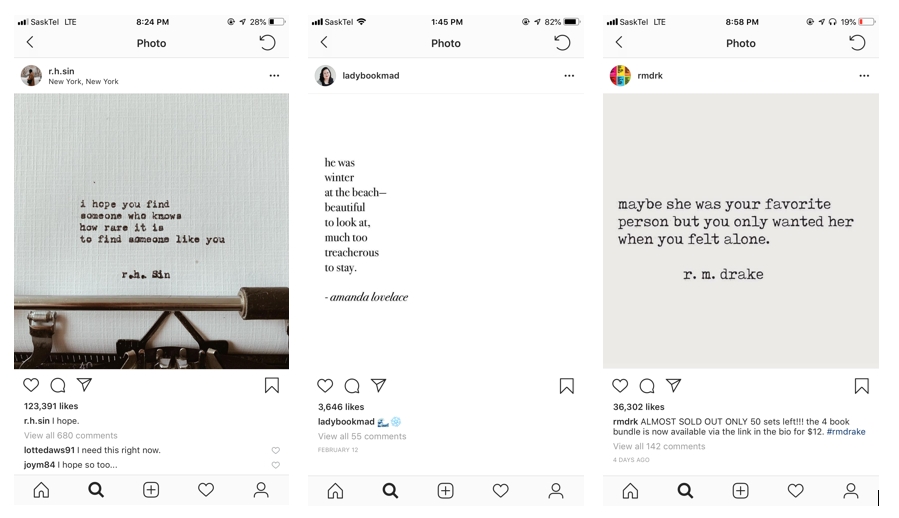

If you have a social media profile and are yourself a teen or twenty-something, chances are that in the past few years, you’ve seen poetry popping up on your screen as you scroll along on your laptop, smartphone, or smart refrigerator with a built-in screen. You have also probably noticed that no, this poetry isn’t the work of Chaucer or Shakespeare, Wordsworth or Whitman, Pound or Plath, or any other canonical poet that you most definitely read thoroughly (and did not use SparkNotes for at all) in English classes of the past. Upon taking a closer look, you might see names like Rupi Kaur, R. M. Drake, r.h. Sin, Nikita Gill, and Amanda Lovelace appear beneath these poems. Combined, these ultra-contemporary internet poets have well over 7 million followers on Instagram. In an interview with poet Rupi Kaur, arguably the most well-known of these poets with 3.6 million Instagram followers of her own, Jimmy Fallon offhandedly states that “poetry is the new pop, man” (“Rupi Kaur Reads” 0:08). So, who are these popular poets, and what do they want from us? Beyond that, if almost everyone rolled their eyes at poetry in grade school, why is it so trendy now? Are we all in the middle of a poetry renaissance in the digital age?

Before tackling these questions, some introductions are in order. If you haven’t yet been formally introduced, please let me do the honours. Blog post reader, meet Instapoetry.

Images: mobile phone screenshots from https://www.instagram.com/r.h.sin/, https://www.instagram.com/ladybookmad/, and https://www.instagram.com/rmdrk/

I use the term Instapoetry to describe this phenomenon as I will be focusing specifically on the poetry that gets posted to Instagram and, conveniently, because the term itself reflects the instantaneous nature of self-published poetry on the web. Notably, although Instapoetry can vary in content, the poems do share a) a general poetic form & style and b) a common platform. Both elements offer one avenue towards popularity that anthologies of poetry simply cannot compete with: approachability.

The Poetic Form and Style

As YouTuber divya g points out, when referring to poetry shared on social media, “some people call it modern poetry. Some people call it art. Some people call it tumblr-insta-poetry. And some people call it ‘My caps lock is broken and no longer works!’” (“basic wannabe” 1:15-1:35). Regardless of the name you give it, you are bound to recognize some common features in the poetry itself: lowercase letters, frequent line breaks and enjambment, simple diction, straightforward metaphors, plenty of surrounding white space, and at times corresponding minimalistic graphic design.

Image source: https://www.instagram.com/rupikaur_/

You could argue – and many do – that these stylistic and formal features make the poems appear less like poems and more like easily relatable one-sentence phrases, haphazardly broken up using the enter key. Poetic quality aside, however, these features are exactly what makes the poems so approachable. Readers can easily understand the poems without feeling intimidated by elevated diction or put off by complicated figurative language. Some poets even post excerpts of full poems, making for purposefully quick reads. As the poems are generally short and not designed to be puzzling, the reader can react by seeing themselves in those relatively vague statements or by being inspired by their simple messages.

These ultra-contemporary internet poets want us to feel, and like many writers, they want as many eyes on their work as possible. An easily-approachable form and style? Check. Next up? An easily-accessible platform.

The Platform

As a platform for publishing, websites like Instagram have really changed the game for poetry and its popularity. Simply put, social media has allowed writers the complete freedom to self-publish and make their writing available for anyone with an internet connection to see (Carolan and Evain 289). In turn, anyone with an internet connection can look for and come across that work.

In a CTV news interview with Your Morning, poet Nikita Gill noted that “poetry, for a long time, has been very much academic,” and went on to note that “it’s interesting to try and make it accessible and try and bring it to such a big audience. And it’s wonderful to see so many people connect with it over a platform like Instagram” (“After being rejected” 0:49-1:09). Having been rejected by traditional book publishers more than one hundred times, Gill built a supportive audience online and ended up getting the book deal she wanted. And she’s not the only one. Many successful poets end up publishing their work in physical forms. Physical books, however, are not the end goal. Rupi Kaur, for example, has written and profits from two physical collections of poetry, and even though she could publish her poetry strictly in this traditional format, she continues to upload multiple poems to her Instagram page each week. In doing so, she keeps her followers engaged and allows those who may not be able to get their hands on her published books the opportunity to keep up with her work.

Why I Care and Why Any of This Even Matters

My first encounter with poetry posted on social media actually occurred back in 2013 on Tumblr, during what I might now consider the height of my angsty teen years — truly, the perfect time and place to absorb some nice and short, easily-digestible, and emotionally-saturated creative writing. A quick nostalgic (and in many ways cringe-inducing) trip to the archives of my old blog shows how much I lived for “reblogging” poetry found under the hashtags #poetry, #writers on tumblr, and #spilled ink. This is all to say that self-published poetry has existed for quite some time on social media, surely before I encountered it, and that Today’s Youth™ (and young adults) seem to be great target audiences for the genre. Since my years on Tumblr, I’ve even seen the likes of these poems reposted on social media platforms from Facebook to Pinterest, and I can’t imagine seeing the influx of on-screen-poetry slowing any time soon.

Instapoetry matters because for many people, it’s the only form of poetry that they will give the time of day, and could this really be a bad thing if it means exposure to and interest in poetry is increasing? It also matters in that it reflects how we read on social media, as the likelihood that we’ll stop scrolling long enough to read hundreds or thousands of words is slim, which makes short, simple poems like these all the more appealing. Instapoetry’s popularity perhaps even indicates millennial and Gen Z’s subcultural movement towards being a little bit more vulnerable online (or at times towards creating the image of vulnerability).

In the spirit of the topic at hand and drawing from my experience reading it, I’ve quickly written a (spoof?) Instapoem of my own:

i was the one free essay

extension

and you were

the desperate student

you used me

once

the first chance you got

i won’t let you use me again

Okay, so I was hoping to end on a comic note and accidentally ended up getting a little real … but then, getting real online seems to be part of the goal with Instapoetry, so maybe it’s fitting after all. Whether Instapoetry for you serves as a gateway for other types of poetry or leaves you satiated with what it provides alone, I think it’s great that poetry, as a concept, is getting out there. And although there is no unanimous consensus about the quality of these poems and their status as poetry – that is very much a blog post topic in and of itself for another time – it can’t be denied that the form, style, and platform of Instapoetry has made both publishing poetry and reading poetry approachable in ways that it really couldn’t have been prior to the digital age.

Works Cited and Consulted

“After being rejected by 137 publishers this poet made it big on Instagram | Your Morning.” YouTube, uploaded by Your Morning, 7 June 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=RHEfAPRuS_o

“basic wannabe instagram girl reviews basic instagram poetry.” YouTube, uploaded by itsdivya, 23 September 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=7TYPfuaqpAQ

Byager, Laura. “Roll your eyes all you like, but Instagram poets are redefining the genre for millennials.” Mashable, 19 October 2019, https://mashable.com/article/instagram-poetry-democratise-genre/#b0RPP5z8bsqM

Carolan, Simon, and Christine Evain. “Self-Publishing: Opportunities and Threats in a New Age of Mass Culture.” Publishing Research Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 4, 2013, pp. 285-300. doi: 10.1007/s12109-013-9326-3

Hill, Faith, and Karen Yuan. “How Instagram Saved Poetry: Social media is turning an art form into an industry.” The Atlantic, 15 October 2018, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/10/rupi-kaur-instagram-poet-entrepreneur/572746/

Johnson, Miriam. “The Rise of the Citizen Author: Writing Within Social Media.” Publishing Research Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 2, , 2017, pp.131-146. doi: 10.1007/s12109-017-9505-8

Khaira-Hanks, Priya. “Rupi Kaur: the inevitable backlash against Instagram’s favourite poet.” The Guardian, 4 October 2017, www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2017/oct/04/rupi-kaur-instapoets-the-sun-and-her-flowers

“Rupi Kaur Reads Timeless from Her Poetry Collection The Sun and Her Flowers.” YouTube, uploaded by The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, 26 June 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=EHkFFA5iGlc

“Why Rupi Kaur and r.H.Sin are Popular.” Reddit, discussion thread posted by paradoxicalme, 18 January 2019, www.reddit.com/r/books/comments/ah9mxx/why_rupi_kaur_and_rhsin_are_popular/?st=JR2J20D7&sh=ac7d3615