Brianna Kaminecki

I read Frankenstein, also known as The Modern Prometheus, by Mary Shelley for the first time in my second year of high school. I learned quickly that Frankenstein was actually the doctor who had created the big, green monster kids associate with Halloween rather than the monster himself. While I did not initially enjoy its length at the time, I did come to appreciate its story because it genuinely scared me to think that some scientist could take corpse’s body parts and create new life from the combination of them by sewing them together like a mix-and-match ragdoll and bringing this new body back to life. He was not a cute, green, animated Halloween figure, but the unfortunate experiment of a scientist. I had a lot of questions after finishing the novel, most of which stemmed from paranoia. What if the story was real? Can scientists do such things? What if I had walked by such a specimen in the street and just had not noticed? All are unlikely, but the story produced this kind of thinking in my mind. While the plot of Frankenstein is purely fiction, I was missing out on a true story just beneath the novel’s surface: the story of its printing.

Its writing began in 1816 in Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Mary Wollstonecraft, a teenager, was staying with her future husband Percy Shelley, who was married at the time, Claire Clairmont, John Polidori and Lord Byron who suggested they each write a ghost story to pass some time (British Library). Doing so, she wrote hers about a scientist, Victor Frankenstein, and the monster he created, Adam. Initially, it was a short story that she wrote because of Lord Byron’s spontaneous scary story idea, but Percy Shelley urged her to expand it (Queralt). She did so and drew inspiration from his support, as well as the scientific advances that occurred during the Enlightenment. A significant experiment was done by Luigi Galvani in 1786, where he electrically stimulated frog nerves causing the frog’s body to twitch (Dibner). While it may not have been a direct influence, it demonstrated the progress science was making in the eighteenth century and Mary Shelley’s view of the dangers of science going too far in an age where science and religion were conflicted (Queralt).

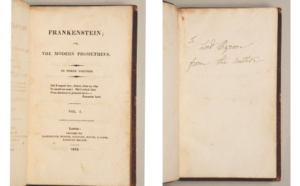

Frankenstein was first published on January 1st, 1818 in three volumes. By this time, Mary Wollstonecraft had married Percy Shelley and had been married to him for almost two years. This first edition was not published under her name but anonymously with a preface by her now husband. Shelley was in collaboration with her husband, and he edited her work but was not the author. The manuscripts Bodleian MS Abinger c.56, Bodleian MS Abinger c.57, and Bodleian MS Abinger c.58, are her drafts for the novel and the first edition of the novel respectively, all of which survive and feature her handwriting as well as her husband’s editing. Each manuscript can be found in the Shelley-Godwin Archive (linked below). There is disagreement as to who really wrote the novel, but these manuscripts show that Mary Shelley’s hand is more present than her husbands and argue for her authorship (The Shelley-Godwin Archive).

The first edition of Frankenstein given to Lord Byron from the author, Mary Shelly.

(Image courtesy of Peter Harrington)

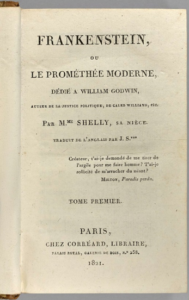

An 1821 French translation of the novel was the first time Mary Shelley was given credit as the author of Frankenstein. It was published by Corréard in Paris and listed the author to be “M.me Shelly” while the title remained the same, but was translated by Jules Saladin to Frankenstein, ou le Prométhée modern (Wikipedia).

The 1821 translation of Frankenstein crediting Mary Shelley as the author.

(Image courtesy of Gérard Oberlé)

A second English edition was published in 1823, about a year after her husband’s death, in two volumes and was the first English edition in which she was known as the author and is featured on its title page. This featuring of her on the title page was surely something she was proud of despite her husband not living to see it.

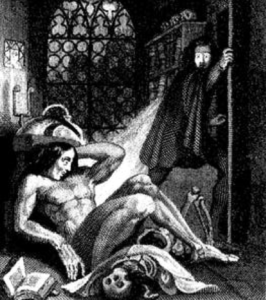

Finally, in 1831 it was published again in one volume with thorough revisions. This third edition is the most well-known version of the novel in the twenty-first century (Queralt). It features an engraving which depicts the “monster” of Shelley’s novel for the first time. He looks very different from how we have seen him presented in our childhood Halloween movies.

The third edition’s engraving of the creature, Adam.

(Image courtesy of D.J. Tice of the Star Tribune)

It is extraordinary to see how this novel has survived not only physically but also within the minds of people two hundred years later. It poses serious questions about science, religion and the human race. It is a novel to be appreciated because it is more than just a daily reading assignment but a real experience which readers can enjoy for both its story and meaning. It is interesting to me personally to see how it progressed being published and printed three different times because it seems as though it only improved. I fear that prior to this blogpost I saw this novel as nothing more than someone writing a book and publishing it, when there was a story of a young, female author to be explored. Novels are more than just their plots; they are also the stories of how they came to be published and printed.

Works Cited and Consulted

British Library. All Discovering Literature: Romantics and Victorians works. n.d. 11 January 2019. <https://www.bl.uk/works/frankenstein>.

Dibner, Bern. Luigi Galvani. 30 November 2018. 13 January 2019. <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Luigi-Galvani>.

Harrington, Peter. The novel – Frankenstein in pictures. n.d. 13 January 2019. <https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/culturepicturegalleries/10273161/Frankenstein-in-pictures.html?frame=2353491&page=-5>.

Oberlé, Gérard. n.d. 15 January 2019. <http://www.bibliorare.com/products/shelley-mary-frankenstein-ou-le-promethee-moderne-paris-correard-1821/>.

Queralt, Maria Pilar. How A Teenage Girl Became the Mother of Horror. 26 October 2017. 12 January 2019. <https://www.nationalgeographic.com/archaeology-and-history/magazine/2017/07-08/birth_of_Frankenstein_Mary_Shelley/>.

The Shelley-Godwin Archive. Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. n.d. 11 January 2019. <http://shelleygodwinarchive.org/contents/frankenstein/>.

Tice, D.J. Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein”: a creation for the ages. 10 June 2016. http://www.startribune.com/mary-shelley-s-frankenstein-an-creation-for-the-ages/382541661/. 13 January 2019.

Wikipedia. Frankenstein authorship question. 13 January 2019. 15 January 2019. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankenstein_authorship_question>.