Mason Kelliher

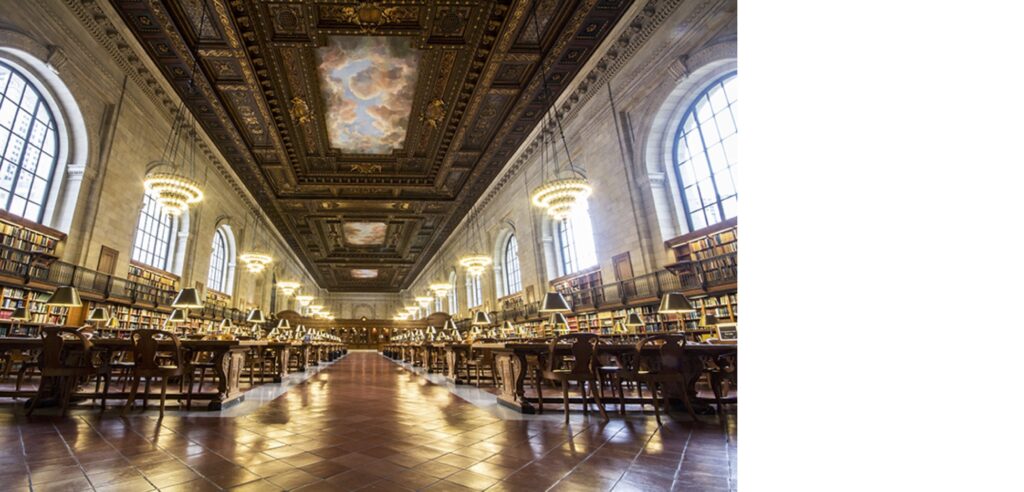

There have been many renovation plans for the New York Public Libraries over the years. In my blog post I went over the past and current plans for the Stephen A. Schwarzman building and how they were going to exile millions of books to a storage unit so that they could remove the historical stacks and make the library more modern. Ultimately, they decided to scratch this idea and relocate some of the money to the Mid-Manhattan location and Bryant Park. This way any books added to the Schwarzman library can be easily accessible as Bryant Park is right across the street. In this article I will be furthering the discussion of the NYPL past and future renovations, but more so on the changes in structure and goal for providing people with the opportunity to learning centres for all ages, access to free Wi-Fi, business building centres for entrepreneurs, and many more other resources that go far past the idea of providing books for people.

Figure 1: Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/locations/divisions/general-research-division

There are many small things that the everyday person takes for granted, such as power, clean water, education, a roof over their head, internet and many other things that the average person from Saskatoon assumes is nearly assured all over. I read a couple articles about the NYPL initiative to provide for everyone, especially the ones that may not be able to financially be able to pay for such resources. Tony Marx, the CEO of The New York Public Libraries, when discussing the vision of their libraries told a few stories on what makes the need for them to provide more than just the regular library “One early morning before the library opened, a man was spotted settled in outside over behind the dumpsters—the dumpsters!—working on his laptop. He had found a strong library Wi-Fi signal right there and was getting some work done while the library was still closed” (Fallows, par. 9). Later in this article Deborah Fallows notes that over 3 million people in just New York can’t afford internet (par. 7). This led me to look into the poverty rates of New York which in 2018 was reported that a staggering 14.1% of people were in poverty, which meant that a household was making less than $24,860 annually (TalkPoverty.org). Talk Poverty reported the population in 2018 of New York was 19,337,685 and 14.1% of that is 2,722,257, which means that there were still families that essentially couldn’t afford to live, but still had to allocate money towards internet. The NYPL provides over 10,000 internet modems for free for people to use, which not only helps the people who may be able to afford internet, but for the people who are in poverty that monthly savings help immensely (Fallows, par. 4).

The NYPL allows the homeless to come and stay, use the resources, and even help them with filling out applications for jobs. Fallows goes on to tell a story she heard from Columbus, Ohio, “Education efforts in Columbus libraries are a continuum from the kids on through “life skills” for adults. This means adult literacy programs, career and technology literacy, and financial literacy. Here is a true story that gives a sense of the realities: A young man comes into the library seeking help with a job search and filing his application for work. A librarian helps him load the application onto the screen. They agree he’ll fill it out and she’ll return to look it over. The librarian returns to discover the man has completed the application, not by keying in the responses, but with a marking pen on the screen” (par. 11). Obviously, this is an extreme case of someone who wasn’t able to be educated with computers in his upbringing, but it does show that there is a further need for such resources to be provided. If these resources had been available even 10 years earlier it would have potentially allowed children coming from a family in poverty, homeless, or even elderly people the ability to do applications or learn basic things that could potentially help them get a higher paying job or in some cases a job in general. Speaking of elderly, the number of senior citizens working is increasing every day, and mostly it’s not by choice. Richard Dever, 74, did an interview with The Washington Post, where he said I’m going to work until I die, if I can, because I need the money. I drove 1,400 miles to this Maine campground from home in Indiana to take a temporary job that pays $10 an hour. (Jordan and Sullivan, par. 2). Dever obviously has work experience in his 74 years on earth, but why is he having to work for 10$ an hour and 1400 miles away? In my opinion it’s because it’s a new world out there. Things get thought out more thoroughly and efficiently these days. Such a high number of things these days are done with a computer or because a program on the computer told us it’s the way it should me. How does this relate to the elderly? The fact that computers didn’t become a key part of society until they were nearly set to retire for the first time, or when they anticipated to being able to retire. Jordan and Sullivan write “People are living longer, more expensive lives, often without much of a safety net. As a result, record numbers of Americans older than 65 are working — now nearly 1 in 5. That proportion has risen steadily over the past decade, and at a far faster rate than any other age group. Today, 9 million senior citizens work, compared with 4 million in 2000” (par. 4). Now it’s too late for the NYPL to go back and make the decision to provide people with these resources, but the fact that they have done it now is extremely important. By helping elderly people come to the library and learn how to navigate through a computer free of charge or take classes there will help them get job opportunities that could be easier for an older individual. In relation to kids that are unable to have internet at home or don’t live in the best area, they are able to go to their closest library and get the education they need. This will allow them to not fall behind the people who are much more fortunate.

In my opinion what the New York Public Library is doing on their own is extremely important, but this biggest positive of this is the influence it has had and will have on future libraries and organizations. Coming a little closer to home, the Toronto Public Library had an article by the star Columnist Bob Hepburn, who said “When we think of places where homeless people hang out during the day, our thoughts likely turn to park benches and downtown sidewalks. But the reality is that our public libraries, especially those in hard-pressed neighbourhoods in Toronto, have become the place to go for growing numbers of homeless men and women seeking refugee from the heat, cold, snow and rain — or the hard life on the streets” (par. 1). This is a perfect example of using what you have and getting the most of it. Hepburn notes that they have hired a social worker to help with the homeless or people in need and that they are welcome as long as they wish as long as they’re not disturbing anyone (par. 5). Such moves may upset non-homeless patrons who are disturbed when they see the homeless lingering in their local branch. But the Toronto library is taking the right step in trying to deal with the issues facing the vulnerable people who pass through their doors every day. More library systems should follow in Toronto’s footsteps and look at ways to help their homeless patrons, such as offering special programs and raising employee awareness of how to take an empathetic approach to homeless people in their branches (Hepburn, par. 11). It’s their priority to help everyone that steps in through their doors, but it’s very encouraging that that they do acknowledge that the homeless people in this situation take priority as they truly are in need. The way the article is written it makes it seem like they are almost taking credit for the steps taken and are the main influencer, but the Toronto based article is from 2018, while the NYPL article is from 2015. The first to promote helping people in need and giving resources to help truly doesn’t matter. What matters is that others are taking notice and making a change all across North America.

One of the largest supporters of Toronto’s public libraries and other supports for the homeless is Emilio Estevez. At a shared release of The Public, a film by Emilio Estevez that covers a two-day period when homeless patrons occupy the main Cincinnati library during a severe winter cold snap (Hepburn, par. 9). Having a big public figure openly talking, let alone producing films about the situation, will surely help promote and influence others to join the cause.

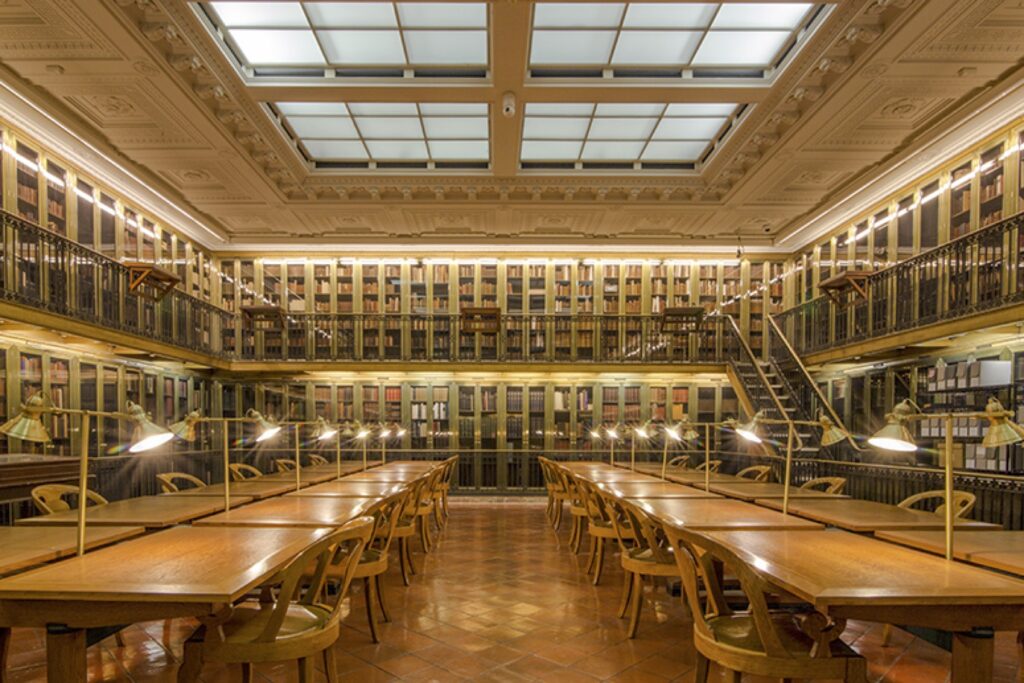

Figure 2: Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/locations/divisions/rare-books-division

When you look at the changes the NYPL has made over the last couple years, you can’t but think that they have nailed their choices. Whether that be scrapping the renovation plans of the Stephen A. Schwartzman building and making millions of histories important pieces readily available to the public or recognizing the way society is these days with the need to help education and provide for those in need. Emilio Estevez goes to say “We’ve got to do something. We’ve got to try” (Hepburn, par 18), which can’t be more straight forward. If the NYPL, Toronto libraries, you, or me keep trying to make a difference for the better, it will only improve the life of the homeless, poverty, children, elderly and everyone involved.

Works Cited

“Back to Poverty – New York.” Talk Poverty, 19 April. 2019, www.talkpoverty.org/state-year-report/new-york-2018-report/

Fallows, Deborah. “The New New York Public Library.” The Atlantic, www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2015/06/the-new-new-york-public-library/397322/. Accessed 19 April 2019.

Hepburn, Bob. “How Our Libraries Can Help the Homeless” The Star, /www.thestar.com/opinion/star-columnists/2018/09/19/how-our-libraries-can-help-the-homeless.html. Accessed 19 April 2019.

Jordan, Marry. Sullivan, Kevin. “The New Reality of Old Age in America.” The Washington Post, www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2017/national/seniors-financial-insecurity/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.369e39580ce0. Accessed 19 April 2019.