Overview

Figure 3-1: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/0742/4737235897/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0

Figure 3-2: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ponteminho4.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Dantadd.

In module 2, we introduced the concepts of cosmopolitanism and communitarianism as well as four important dividing lines between them: the permeability of borders, the appropriate locus of political authority, the normative value of community, and the questions of defining as well as achieving justice at the global level. These dividing lines, as well as the essentialized positions of cosmopolitanism and communitarianism, layout two starkly different views. On the one side, we see preferences for more permeable borders, a need for meaningful supranational political authority, a privileging of the universal community of all humanity, and global justice defined through the defence of individual rights in every place for every person. On the other side, we see preferences for harder borders, a deep skepticism of supranational political authority, a privileging of national or sub-national communities, and global justice defined through the defence of self-determination and cultural protection. After this discussion, it would be natural to assume one side is ‘right’ and the other ‘wrong’ – which is which depends on whether you are a person from somewhere or a person from anywhere.

Figure 3-3: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/nagy/4658629/Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Craig Nagy.

However, some will argue the world is much more nuanced than this. They will argue that the world is more complicated than the clear bifurcation between cosmopolitanism and communitarianism might suggest. The English School offers an alternate view of the tension between these two positions. They argue that the world is constituted by three different logics. An international system defined by power politics with interaction occurring at state boundaries and with little meaningful interaction between states. An international society defined by the institutionalization of at least a minimal degree of interests, values, and norms shared between sovereign states and with the goal of establishing international order. And finally, a world society defined by a privileging of the individual and of human rights with the goal of achieving individual justice as the ultimate purpose of global politics. Unlike many schools of international thought, the English School argues that all three of these logics are operating simultaneously in different places at times. Think of the logics at work in the European Union versus India-Pakistan, Israel-Iran, or North Korea-South Korea. The former has created a bloc of 28 members without any internal borders. The latter is characterized by hostility at times and even poses a potential threat of nuclear annihilation.

Moreover, the English School is not teleological – it does not argue we are necessarily moving from a world system towards an eventual world society. Rather, it argues that norms, values, interests, and identities between actors may thicken or weaken, move back and forth, over time. Finally, the international society is the dominant logic of the English school and comes in two distinct forms, a pluralist variant which adheres most closely with a state-based international order and a solidarist variant which adheres most closely with a cosmopolitan approach to international order. Some critique the English School for its lack of theoretical clarity and, despite claims to the contrary, it's privileging of cooperation over the predictions of realpolitik. However, we will suggest in this module, the English School offers a very useful framework for understanding the shifting dynamics of international politics and the concept of global citizenship by taking into account the tension between individuals/states, cooperation/conflict, and order/justice. After finishing this module, we will turn from the theoretical and begin to look at the practical aspect of global citizenship by examining the meaning and application of globalization.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

1. Outline the differences between an International System, International Society, and World Society

2. Distinguish between the pluralist and solidarist variants of the international society logic of the English School

3. Apply the English School’s multilayered approach to understanding global citizenship

1. Read Buranelli, Filippo Costa. “The State of the Art of the English School” System, Society and the World. E-International Relations. 2015

2. Read Murray, Robert. W. “Introduction” System, Society and the World. E-International Relations. 2015

3. Take the English School Quiz

4. Complete learning activity one

5. Read the IR and All That blog entry ‘International Theory: The Three Traditions’ http://irandallthat.blogspot.com/2011/07/international-theory-three-traditions.html

6. Complete learning activity two

7. Watch the Al Jazeera video “Humanitarian intervention or imperialism?” https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/headtohead/2014/11/humanitarian-intervention-imperialism-2014111093042592427.html

8. Complete learning activity three

9. Think for a moment about the three logics of the English School and the concept of global citizenship

10. Complete learning activity four

Absolute gains

Coexistence

Convergence

Customary international law

Grotian world

Hobbesian world

International society

International system

Kantian world

Natural law

Norm of non-interference

Pluralist

Positive international law

Zero-sum game

Responsibility to Protect

Social contract

Solidarist

Sovereign nation states

State of nature

The Anarchical Society

The English School

World society

Zero-sum game

Buranelli, Filippo Costa. “The State of the Art of the English School” System, Society and the World. E-International Relations. 2015.

Murray, Robert. W. “Introduction” System, Society and the World. E-International Relations. 2015

Learning Material

Figure 3-4: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/rodneydunning/36371278772/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Rodney Dunning.

Is the world black and white? Are we living in an increasingly open, cosmopolitan world? A world where borders mean less? Where rights are increasingly universal? Or are we seeing an increasingly closed, communitarian world? A world where communities make sharp distinctions between ‘us’ and ‘them’? If we look at our news and listen to our politics, it might seem like one side must be right and the other side must be wrong. There is little nuance, little middle ground… no grey, only black and white. The English School offers a stark contrast to this view, seeing a world full of grey. It attempts to make sense of a world of cooperation, think of the economic cooperation in the World Trade Organization. And a world of conflict, think of North Korea or Israel and their neighbours. It attempts to understand a world of eroding borders, think of the European Union. And a world where they are hardening, think of the US-Mexico border. It understands the world to be constituted by sovereign nation-states that occupy a privileged position in global politics. Yet it also takes into account increasingly important civil society actors like Greenpeace or Amnesty International as well as Multinational Corporations like Walmart, Toyota, or Royal Dutch Shell. It recognizes the principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of sovereign states. And, at the same time, it recognizes the power and legal force of the Responsibility to Protect which makes that sovereignty conditional on protecting its citizens from gross human rights abuses. The English School defines global justice both as orderly conduct between nation-states and as the articulation and defence of universal human rights.

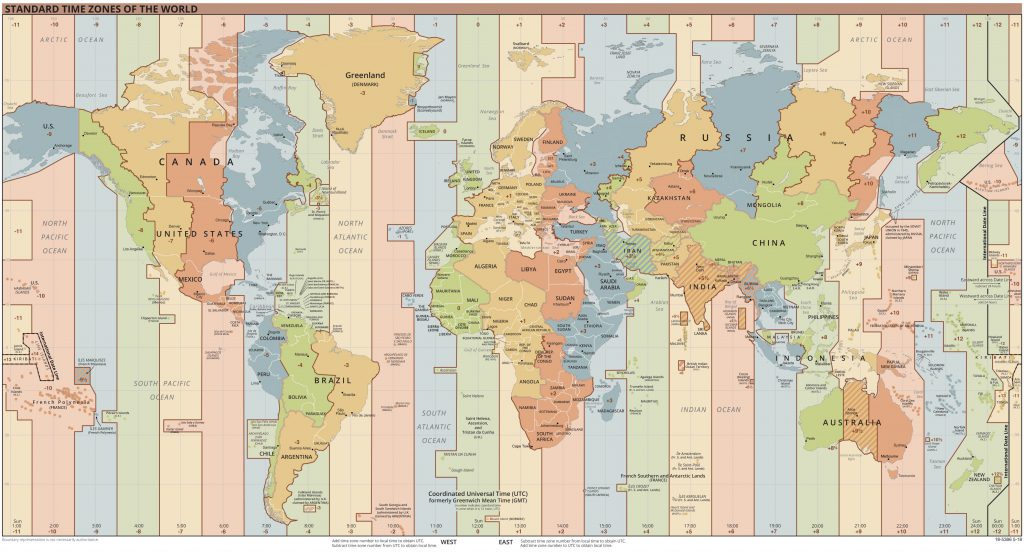

Figure 3-5: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Standard_World_Time_Zones.png#/media/File:Standard_World_Time_Zones.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Hellerick.

Figure 3-6: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/nutshell-security-insecurity-2122627/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of johnhain.

Putting this into the context of this course, the English School is able to account for both the communitarian and cosmopolitan positions. It does so by positing that our world is constituted by three distinct logics: an international system, an international society, and a world society. Together these three logics represent a continuum, with a Hobbesian world of conflict and distrust on one side and a deeply interconnected Kantian world built on individual rights on the other. Unlike most ideologically/theoretically rigid accounts of global politics, the English School is deeply immersed in history and uses this as a means to test the various claims made in its name. While most English School theorists suggest the international society is the dominant logic of contemporary global politics, they also recognize that the other two logics are operative in different places and at different times. Within the logic of the international society itself, English School theorists identify two distinct variants: pluralist and solidarist. The pluralist variant of an international society understands the world to be constituted by sovereign states which operate on a minimalist set of agreed-upon norms/rules. The goal from this perspective is to achieve an ordered international society. The solidarist variant of an international society understands the world to be converging around an increased number of important norms and values that have to do with individual rights. The goal from this perspective is to achieve a just international society. If we apply the insights generated by the English School to global politics and global citizenship, we may be able to gain a better appreciation of the tensions within these concepts. This will be useful when we turn to the processes of globalization in the next module.

Before moving on, let us where you fall on the spectrum of the English School. Take the quiz below and report your findings using the poll.

Figure 3-7: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/katerkate/517193121/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of katerkate.

Figure 3-8: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/mafue/5847613692/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Matt Boulton.

Most approaches to understanding global politics tend to focus on a specific configuration of actors, power, and issues. For example, in the last module, we introduced cosmopolitan thought which posits a world that is less defined by sovereign states and more defined by deeply interconnected networks constituted by individuals. Communitarianism, on the other hand, posits a world constituted by discrete communities which protect and give meaning to members of society. Each school of thought can defend its position by isolating specific configurations of actors, power, and issues. Cosmopolitans privilege individuals, the need for supranational authority, and transnational issues like environmentalism, transnational crime, transnational terrorism, and human rights. Communitarians privilege the state or other ethnic/religious communities, national sovereignty, and issues like self-determination, democracy, and defining the common good. Each can support its claims through a selective reading of history and cherry-picking examples. Cosmopolitans point to the European Union, the International Criminal Court, and the World Trade Organization. Communitarians point to the contentious relations between Israel and its neighbours, the coercive influence of the super-powers in international institutions, and the prevalence of conflict throughout history. A primary point of contention between the two positions is the relevance and power of the state. Cosmopolitans either argue it is in decline or should be. Communitarians either argue it is as important as ever or should be.

Figure 3-9: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/mafue/5847613692/ Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0

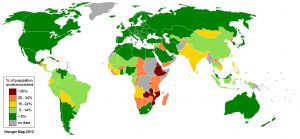

Figure 3-10: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Percentage_population_undernourished_world_map.PNG#/media/File:Percentage_population_undernourished_world_map.PNG Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Lobizón.

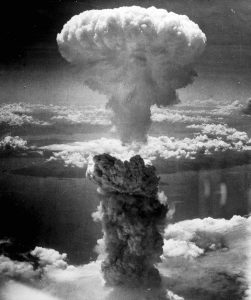

The English School, on the other hand, takes a very different approach, what some might call a ‘grand theory’ of international politics. It emerged in the post-World War II era out of a dissatisfaction of theories that privileged conflict or cooperation, states or individuals, universal values or particular values. Instead, English School academics started with a deeply historical approach to understanding global politics. They recognized the historical and contemporary centrality of the state in global politics but also the rise of influential international institutions, MNCs, and global civil society. They recognize the potential of supranational projects like the EU or the WTO which challenge the sovereignty of the state. But they also recognize the deeply insecure condition of global politics, the tension between North Korea and South Korea for example, the potential nuclear showdown between the US and the USSR during the Cold War, the potential trade war between the US and China, or failed states like Somalia.

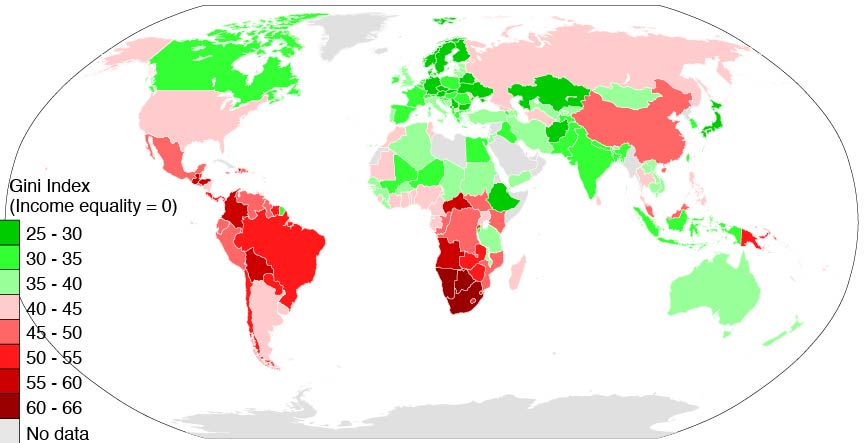

Figure 3-11: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2014_Gini_Index_World_Map,_income_inequality_distribution_by_country_per_World_Bank.svg#/media/File:2014_Gini_Index_World_Map,_income_inequality_distribution_by_country_per_World_Bank.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of M Tracy Hunter.

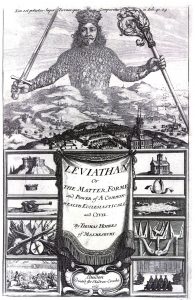

Figure 3-12: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leviathan_by_Thomas_Hobbes.jpg#/media/File:Leviathan_by_Thomas_Hobbes.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 3-13: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nagasakibomb.jpg#/media/File:Nagasakibomb.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Charles Levy – U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

The most important insight to come out of the English School is that the world is a complicated place and theory needs to take account of this. It is simultaneously constituted by differing levels of shared norms and values in different places. Some areas of the world are constituted by little to no shared norms and values. States are deeply distrustful of each other. Any cooperation is a function of necessity or grudgingly arrived at with deep unease. Other areas of the world are constituted by deeply shared norms and values. Here, the state is seen as less necessary in the defence of citizen security and individuals have come to expect and demand more freedom from state authority. Their interests and identities increasingly transcend and may actually challenge the sovereignty of states. To make sense of this diversity, the English School has identified three simultaneous logics to global politics: the international system, the international society, and the world society. An international system is often described as a Hobbesian world. Thomas Hobbes, in response to the brutality of the English Civil War (1642–1651), argued that without a centralized authority we live in a state of nature defined by anarchy. Life in this state of nature is characterized by “continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” This can be overcome domestically by empowering a centralized authority, or sovereign, to enforce the conditions of a social contract and bring order to society.

In global politics, Hobbes is often invoked since there is no higher authority than the sovereign state. States, therefore, live in an anarchical state of nature, where conflict is not only possible but expected. The international system is therefore defined by distrust and privileges prudence with outcomes achieved through the exercise of power. Decisions between states are seen as a zero-sum game, if I win, you lose, and vice versa. Cooperation is very difficult to achieve since relative gains are the most important decision point, not absolute gains. In other words, it doesn’t matter if both parties benefit, absolute gains, but rather who gains more, relative gains. This is crucial in an international system since if one party gains more than another, that party increases its power and is potentially a greater threat. It is a greater threat because under the condition of anarchy there is no check on one state using its power to force another state to do what it wants. There are clear contemporary examples of the international system at play albeit it less than in the past. The relations between Israel and Iran, for example, are representative of this logic. Both parties are deeply antagonistic towards each other and seek to undermine their respective power. Any gain by either party is seen as an existential threat to the other, especially if those are nuclear gains.

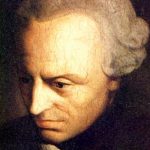

Figure 3-14: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Immanuel_Kant_(painted_portrait).jpg#/media/File:Immanuel_Kant_(painted_portrait).jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 3-15: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Preparing_to_enter_Ebola_treatment_unit_(2).jpg#/media/File:Preparing_to_enter_Ebola_treatment_unit_(2).jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of CDC Global – Preparing to enter Ebola treatment unit.

On the other end of the spectrum is the logic of the world society which is often described as a Kantian world. Immanuel Kant was an 18th-century philosopher struggling with establishing a moral code of conduct to fill a void being created by the undermining of religion’s foundational role in society.

In essence, Kant was seeking a secular definition of what gives an act moral worth. He argued that to find a secular definition of what is good or bad, what is right or wrong, requires an understanding that human beings are free, rational agents. As free, rational agents, all human beings, have inherent worth and dignity. This inherent worth and dignity require us to not simply treat ourselves nor others as means. We must treat ourselves and others as ends in and of themselves. Importantly, this is universal and not particular. We must treat ‘ours’ the same as we treat ‘others’. As applied to global politics, this means focusing on the individual as the basic unit of analysis. It means actively seeking to transcend the state-based system to achieve a deeply interconnected world of universal human rights and universal law. To seek a world where progress, justice, and opportunity are not a function of where and to whom you were born but rather is available to every person, everywhere. There are few clear examples of a world society at work. In some ways, the European Union demonstrates a shift towards a world society albeit at the regional level. This can be seen in the removal of internal borders and the ability of the EU institutions to exercise supranational authority. But we can also see embryonic forms of world society in transnational identities and movements, like Greenpeace, Amnesty International, or Doctor’s Without Borders.

Between the logic of the international system and the logic of the world society, resides the logic of the international society which is often described as a Grotian world. Hugo Grotius, born at the end of the 16th century, is considered to be the father of international law.

Figure 3-16: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Michiel_Jansz_van_Mierevelt_-_Hugo_Grotius.jpg#/media/File:Michiel_Jansz_van_Mierevelt_-_Hugo_Grotius.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Michiel van Mierevelt.

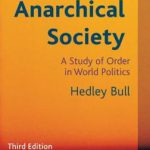

In direct contrast to the Hobbesian worldview, Grotius argued: “states are not engaged in a simple struggle, like gladiators in the arena, but are limited in their conflicts by common rules and institutions.” He does not deny the significant and privileged role of states in global politics but neither does he argue they exist in a Hobbesian state of nature where power is the ultimate determinant of foreign policy decision making. Rather, he argues global politics is constituted by a state system structured by at least a minimalist set of shared norms and values. These norms and values seek to establish predictability and order in global politics through the establishment of institutions and the guidance of international law. Hedley Bull perhaps puts this most succinctly in the title of his 1977 book The Anarchical Society.

Figure 3-17: Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_Anarchical_Society_third_edition_cover.jpg#/media/File:The_Anarchical_Society_third_edition_cover.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

This title captures the central logic of international society. Yes, global politics operates in an anarchical environment as there is no higher legitimate authority than the sovereign state. Yet, within this condition of anarchy, a society of states has formed through diplomacy, international treaties, and international law. At the most basic level, this international society seeks to maintain the state-based order as a primary form of justice. The international society does not preclude higher forms of justice, but neither does it argue it is a natural outcome of the state-based order. We will leave this distinction alone for the moment as it will be the subject of discussion in the next section. The logic of the international society is the one we can see most at work in today’s global politics and therefore has been the most readily adopted aspect of English School theorizing. For example, we can see the state-based order at work in the UN or the WTO but also the role of great power politics in the UN Security Council and the negotiated rounds of tariff reductions in the WTO. We can see the demands for justice after the attack on the Twin Towers on 9/11 but we can also see it in the failure to act on the ethnic cleansing in Myanmar. In other words, we live in a state-based international society that rises above a brutal Hobbesian world of anarchy but falls short of a world defined by universal rights.

Figure 3-18: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:UN_Security_Council.jpg#/media/File:UN_Security_Council.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Thomas Park.

- Read the IR and All That blog entry ‘International Theory: The Three Traditions’ http://irandallthat.blogspot.com/2011/07/international-theory-three-traditions.html

- If you want to read the full article this blog is based on, you can find it here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20096764?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the three English School logics: international system, international society, world society

- Why does the English School suggest all three logics are operating simultaneously?

- Do you agree or disagree? Please explain your position.

Figure 3-19: Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/hzp_aT02R48 Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Louis Reed on Unsplash

Figure 3-20: Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/hzp_aT02R48 Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of I, Inisheer.

For many proponents of the English School, the most important insight is generated by the logic of international society. That is not to say the logic of the international system and the logic of the world society are not operative, but for many, they are not the dominant logic. The international system logic makes sense of conflict-prone regions and states with weak internal structures, but this logic seems to reflect the past, it is something to be overcome. The world society, on the other hand, has appeal but it is less defined and seems to represent a possible, albeit very difficult, goal to achieve. The international society, on the other hand, seems to capture the contemporary dynamics of global politics. Since the 18th century, we have seen a growth of international institutions, international civil society, international law, and international governance. The trend has been towards an increasingly interconnected world in terms of economics, politics, and culture. There seems to be an increasingly solid set of norms, values, and identities that unite more than they divide. And this trend seems to be growing exponentially versus linearly.

That is not to say there have not been setbacks, just ask, if you could, an infantryman in the trenches of World War One, a survivor of the Holocaust, or more recently a survivor of the Rwandan Genocide, the Srebrenica massacre, the Syrian civil war, or the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya in Myanmar.

But unlike past crimes against humanity, these are events that the international community condemns, seeks to resolve, or at least contain, and hopefully learn from – albeit often doing too little too late. The international society logic of the English School captures the essence of these processes and dilemmas. As introduced in the last section, the international society logic argues that global politics is constituted by sovereign states that have, over time, developed a degree of shared norms and values between them. These norms and values are derived from normalized and routinized interaction between states. They thicken over time from interests and treaties to expected modes of conduct and on to international law. They have evolved in different geographic and interest areas at different speeds and to different degrees of enforceability.

Figure 3-21: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/un_photo/3311542781/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of United Nations Photo.

Figure 3-22: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EleanorRooseveltHumanRights.png#/media/File:EleanorRooseveltHumanRights.png Permission: Public Domain.

For example, the laws around trade and finance are far more developed and enforceable than norms of human security. Moreover, these norms and laws have thickened and thinned over time depending on changes in global circumstances. But cumulatively, they have formed an anarchical society of states. However, within the international society logic itself, there are two distinct variants that try to make sense of some of these discrepancies: the pluralists and the solidarists. The pluralists are more pessimistic than the solidarists. They believe that the sovereign state is the highest form of practical political unit possible and that the most we can hope for is to achieve global justice as defined by order. From this perspective, order is achieved through the recognition of sovereignty, the norm of non-interference, and the drafting and enforcement of positive international law. Let us look at each of these points in turn. Pluralists argue that if we look at the world as a whole, there are simply too many economic, political, and cultural configurations within states and regions. The sheer number of such configurations would preclude the formation of shared norms and values beyond a minimalist agreement on the need for order. Any attempt to enforce a set of shared norms and values beyond order would most likely reflect the interests of dominant actors. This would lead to an unstable global order due to the festering discontent of those whose identities and interests were not accounted for. Therefore, for pluralists, sovereignty is an important means to achieve global order. People have the right to determine their own political, economic, and cultural structures based on their own norms and values. Sovereignty therefore cleanly divides the domestic and international spheres of politics. An important corollary to the idea of sovereignty is the norm of non-interference. This means that as long as a state’s actions do not spill over into global politics, no other state or institution has the right to interfere in their domestic affairs. States must be held to international treaties and agreements, but domestic politics is off the table. This leads to the third pluralist proposition, the importance of positive international law. Positive international law is based on negotiation and adhered to because of contractual obligations. Positive law is the most clear-cut category of international law. If a state signs an agreement and is found in breach of that agreement, it has broken international law. The penalties for doing so may vary according to the original agreement and the relative weight of the parties involved, but a clear case can be made that the law was in fact broken. This stands in contrast to natural law or customary international law. Natural law is a system of justice or rights that are universally applicable and is derived from nature or god. Customary international law derives from the norms which are constituted by the repeated practices of states and other international actors. In other words, if a particular practice is repeated enough times by enough states, it becomes considered normal practice and therefore a source of customary international law. Pluralists do not completely discount these later two legal forms but they do put particular emphasis on positive international law. Positive international law builds on the concept of sovereignty and the norm of non-interference. States are sovereign. Their domestic affairs are protected by the norm of non-interference. Positive international law means they are most beholden to those agreements they have contractually entered into. States are privileged, equal, shielded from external meddling, and together they contractually establish an international society that promotes global order.

Figure 3-23: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/alisdare/32343915050/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Alisdare Hickson.

The solidarists position, on the other hand, is much less pessimistic than the pluralist definition of international society. They do share a belief that the state is a privileged actor in global politics but they disagree on ‘order’ being the highest form of realizable justice. Instead, solidarists believe that international society can evolve to include a much wider range of shared norms and values that integrate states at a much deeper level. Early solidarist approaches included a liberal focus on the individual, both in animating state behaviour and being the ultimate source of state legitimation. This allowed and perhaps even encouraged a focus on universal human rights, human security, and a thin form of universalism or cosmopolitanism.

This early solidarism has evolved in the face of globalization. Advancements in communication and transportation technology have brought us closer together in time and space. International economics, politics, and culture have integrated how we work and how we live. Through these structures and processes of globalization, solidarists argue the norms and values of international society have by necessity broadened and deepened beyond the pluralist conception. From this perspective, international society has reached beyond merely facilitating coexistence. It has reached beyond a focus on relative gains. Instead, it argues that these processes are facilitating a convergence of norms, values, interests, and identities.

Figure 3-24: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Libyan_war_final.svg#/media/File:Libyan_war_final.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Rafy.

The most important distinction between the pluralist and solidarists conceptions of international society rests on a differing view of sovereignty. They both agree that sovereign states are a privileged actor in global politics but they disagree on the basis of that sovereignty. The pluralist account of the international society takes sovereignty as near absolute or at least errs on the side of sovereign rights. If a state has a defined territory, population, central government, and optimally is recognized by other states, it is likely sovereign. The goal of international society, from the pluralist perspective, is to create and maintain order, to maintain co-existence. For the solidarists, sovereignty is part of a social contract both with its citizens and with other states. This means sovereignty is not absolute but rather is conditional on upholding particular norms and values. For example, in the doctrine of the Responsibility to Protect, if a state is unwilling or unable to protect its citizens from gross abuses of human rights, the international community not only has the right but has an obligation to intervene in that state’s domestic affairs.

The R2P is a very dense area of international law and the following is not a fulsome discussion. However, one of its foundational principles is that a state’s sovereignty is dependent on upholding the rights of its citizens. If a state fails to do so, the international community can disregard the norm of non-interference and thereby nullify its sovereignty. Sovereignty is no longer near absolute and instead becomes conditional. Therefore, from a solidarists position, international society has moved beyond co-existence towards convergence even on the most central of norms and values such as sovereignty. However, it is important to note that this does not mean the solidarists variant of international society is the same as a world society approach. The solidarist variant of international society still privileges the state and does not ascribe rights to individuals apart from nor above the state whereas the world society approach does.

- Watch the Al Jazeera video “Humanitarian intervention or imperialism?”

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal:

- Recall that the R2P doctrine not only gives the international society of states not only the right but the obligation to intervene in the domestic affairs of another state if that state is unwilling or unable to protect its citizens from gross abuses of human rights.

- From a solidarists position, this is an example of the international community having adopted, and more deeply internalized, a broader set of norms and values.

- From a pluralist position, this is deeply suspect since the norms of R2P are based on a European set of norms and values. At best, R2P reflects the good intentions of the ‘West’. At worst, R2P represents a form of Western imperialism. Either way, for the pluralists, the imposition of such norms creates discontent among many states. This will lead to a destabilized global order.

- What is the position of former French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner?

- What is the position of Lindsey German?

- What if the position of Barak Seener?

- What is the position of Hamza Hamouchene?

- What do the examples of Libya, Kosovo, and Rwanda tell us about humanitarian intervention?

- How does this discussion inform the tension between the pluralist and solidarist variants of international society?

- Do you agree more with the argument put forward by the pluralist or the solidarist variant of international society? Why?

- Recall that the R2P doctrine not only gives the international society of states not only the right but the obligation to intervene in the domestic affairs of another state if that state is unwilling or unable to protect its citizens from gross abuses of human rights.

Figure 3-25: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/personal-collective-group-knowledge-3285990/Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

- Think for a moment about the three logics of the English School and the concept of global citizenship

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What are contemporary examples of:

- The international system?

- The pluralist variant of the international society?

- The solidarist variant of the international society?

- The world system?

- In what direction do you think contemporary global politics is moving?

- Towards a world society?

- Towards an international system?

- The entrenchment of the international society?

- Support your answer with examples.

- What are contemporary examples of:

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the English School approach to understanding global politics. Rather than taking a narrow view of global politics and arguing for or against a particular logic at work, the English School suggests a more nuanced, historical, and comprehensive view. By surveying global politics in its entirety, the English School has identified three logics operating simultaneously across time and space. The first logic is the Hobbesian world of an international system where states hold a privileged position and operate in a state of nature. In an international system, there are minimal if any shared norms and values between states, with conflict being an ever-present possibility due to the condition of anarchy. Security is more important than freedom. We can see this logic at work between states sitting on the precipice of conflict: Israel-Iran, India-Pakistan, North Korea-South Korea, et cetera. The opposite logic is the Kantian world society. In a world society, the individual is the basis of a system that has transcended the state by enacting a deeply interconnected world of universal human rights and law. It is a system where progress, justice, and opportunity are not a function of where and to whom you were born. It is a system where justice is the same for everyone, everywhere. In between these two logics is the Grotian world of an international society. This is by far the most dominant logic of the three English school approaches. In an international society, the state is a privileged actor much like in the international system. But the state is not operating in a state of nature characterized by a constant war of all against all. Rather, the international society argues that states agree upon a degree of shared norms and values between them. These shared norms and values constitute an anarchical society, created through diplomacy, treaties, and international law. However, within the international society approach, there is disagreement on the degree to which states are able to share meaningful norms and values. From the perspective of the pluralist variant of international society, the sheer scope of different economic, political, and cultural processes at the global level acts as an almost insurmountable obstacle to achieving anything more than coexistence. Rather pluralists argue the goal here should be to foster and maintain a minimal level of shared norms and values to achieve order in global politics. These include privileging sovereignty, the principle of non-interference, and positive international law. The solidarists disagree. They note the increasing range of shared norms and values occurring at the global level, especially in the context of globalization. Rather than coexistence, solidarists look to the convergence of norms, values, interests, and identities, especially around individual rights. Importantly, pluralists and solidarists disagree on the norm of sovereignty. While the pluralists privilege sovereignty and err on the side of state rights, the solidarists argue sovereignty is conditional on the state adhering to shared norms around individual rights. However, both variants of an international society agree that the state is a privileged actor in global politics and that individual rights are not independent of nor do they supersede the state. The importance of the English School approach for our study is that it provides a means to understand how the concept of global citizenship can strengthen or weaken in time and space. As globally shared norms and values thicken, the concept of global citizenship may strengthen. As globally shared norms and values thin, the concept of global citizenship may weaken. The English School approach provides the language and framework to explain how this may happen.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Absolute gains: is the logic that states will likely cooperate with other states as long as all parties gain an advantage from the transaction.

Coexistence: more generally refers to the ability to exist along side other actors in a given system. In reference to the English School, it refers specifically to establishing an ordered existence within an international society.

Convergence: means to merge and move uniformly towards shared norms and values in an international society.

Customary international law: derives from the norms which are constituted by the repeated practices of states and other international actors. Thus, customary international law is sourced from repeated practices that have become a normality.

Grotian world: is derived from Hugo Grotius’ argument that there are common rules and institutions which limit the actions of states in conflict, and global politics is conducted in a system structured by at least a minimalist set of shared norms and values. It is a world where predictability and order in global politics are established through norms and values set forth by institutions and the guidance of international law.

Hobbesian world: is derived from Thomas Hobbes argument that without a centralized authority, we live in a state of nature defined by anarchy. In global politics this refers to the fact that there is no higher authority than the sovereign state that exist in an anarchical state of nature, where conflict is not only possible but expected.

International society: consists of sovereign states that have, over time, developed a degree of shared norms and values between them. It is defined by the institutionalization of at least a minimal degree of interests, values, and norms shared between sovereign states and with the goal of establishing international order.

International system: is the organization of states void of a central authority and defined by anarchy. It lacks any meaningful shared norms and values between states and is therefore characterized the ever present threat of conflict.

Kantian world: is one where the individual is the basic unit of analysis. The explicit goal of such a system is to transcend the state-based system and achieve a deeply interconnected world of universal human rights and universal law.

Natural law: is a system of justice or rights that are universally applicable and is derived from nature or god.

Norm of non-interference: is the idea that as long as a state’s actions do not spill over into global politics, no other state or institution has the right to interfere in their domestic affairs.

Pluralist International Society: is the variant of the international society that believes that the sovereign state is the highest practical political unit possible and that the most that can be hoped for is to achieve global justice as defined by order. Pluralists argue that sovereignty, non-interference, and positive international law are important means of achieving global order.

Positive international law: is an important concept in the pluralist variant of an international socirty. It is based on negotiation and adhered to because of contractual obligation. They are man-made laws that expressly set out agreements between states.

Responsibility to Protect: is the concept that sovereignty of states is conditional on protecting its citizens from gross human rights abuses. If a state is unwilling or unable to protect its citizens from gross abuses of human rights, the international community not only has the right but an obligation to intervene in that state’s domestic affairs.

Social contract: is a reciprocal agreement between the state and its people over the rights, duties and responsibilities owed to one another.

Solidarist International Society: is a variant of the international society which adheres most closely with a cosmopolitan approach to international order with the understanding that the world is converging around an increased number of important norms and values that have to do with individual rights. However, it falls short of a true cosmopolitan order in that it does not argue individual rights are separate nor higher than state rights.

Sovereign nation states: are states with the supreme authority and power to govern its own territory and the people within that territory.

State of nature: is a hypothetical place and time before we had government or even kings where people lived freely without formal rules or laws.

The Anarchical Society: is the influential 1977 book by Hedley Bull which posits that within the condition of an anarchical environment, a society of states has formed through diplomacy, international treaties, and international law that seeks to maintain the state-based order as a primary form of justice.

The English School: is the theory that posits that global politics is simultaneously constituted by three logics: an international system, an international society, and a world society. These three logics create a spectrum of global politics that stretch from a Hobbesian world of potential international conflict to a Kantian world of universal human rights.

World society: is defined by privileging of the individual and of human rights with the goal of achieving individual justice as the ultimate purpose of global politics.

Zero-sum game: is the idea that the benefit of one can only be achieved at the detriment of the other. Thus, for one to gain, the other has to lose.

References

Bellamy, Alex J. 2014. The Responsibility to Protect: A Defense. Oxford : Oxford Scholarship Online.

Blom, Andrew. n.d. Hugo Grotius (1583—1645). Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.iep.utm.edu/grotius/.

Buzan, Barry, and George Lawson. 2017. The English School: History and Primary Institutions as Empirical IR Theory? . May. Accessed October 15, 2018. http://politics.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-298.

Copeland, Dale. 2003. "A Realist critique of the English School ." Review of International Studies 29 (3): 427-441.

CTV News. 2018. The tension between Iran and Israel explained. May 11. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.ctvnews.ca/world/the-tension-between-iran-and-israel-explained-1.3926186.

Dews, Fred. 2013. What Is the “Responsibility to Protect”? July 24. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brookings-now/2013/07/24/what-is-the-responsibility-to-protect/.

Duncan, Stewart. 2017. Thomas Hobbes. January 27. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hobbes/.

Hendrickson, David C. 2011. International Theory: The Three Traditions. July 5. Accessed October 15, 2018. http://irandallthat.blogspot.com/2011/07/international-theory-three-traditions.html.

Hobson, John M. 2000. The State and International Relations . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

Marcus, Jonathan. 2018. Your questions answered on Iran and Israel relations. May 10. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-44069932.

Miller, Jon. 2011. Hugo Grotius. July 28. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/grotius/.

Murray, Robert. W. 2016. An Introduction to the English School of International Relations. January 5. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.e-ir.info/2016/01/05/an-introduction-to-the-english-school-of-international-relations/.

Rauscher, Frederick. 2016. Kant's Social and Political Philosophy. September 1. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-social-political/.

Suganami, Hidemi. 2010. "The English School in a Nutshell." Ritsumeikan Annual Review of International Studies 9: 15-28.

The Foundation for Constitutional Government Inc. n.d. An Introduction to the Work of Kant. Accessed October 15, 2018. https://thegreatthinkers.org/kant/introduction/.

Westacott, Emrys. 2018 . Kantian Ethics in a Nutshell: The Moral Philosophy of Immanuel Kant. January 17. Accessed October 15, 2018 . https://www.thoughtco.com/kantian-ethics-moral-philosophy-immanuel-kant-4045398.

Supplementary Resources

Bellamy, Alex J. International Society and Its Critics. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Buzan, Barry. International to World Society? : English School Theory and the Social Structure of Globalisation. Cambridge Studies in International Relations ; 95. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Navari, Cornelia, and Wiley Online Library. Guide to the English School in International Studies. Guides to International Studies. 2014.

Suganami, Hidemi, Carr, Madeline, Editor, and Oxford Scholarship Online. The Anarchical Society at 40 : Contemporary Challenges and Prospects. First ed. 2017.

Williams, John. "Structure, Norms and Normative Theory in a Re-defined English School: Accepting Buzan's Challenge." Review of International Studies 37, no. 3 (2011): 1235-253.