Overview

Welcome to IS 201! This course interrogates the idea of global citizenship; the idea that, at a minimum, we have rights and obligations that extend past our national borders. Some take this argument even further, arguing that we are part of a global community with inherent rights and obligations owed to each other by the fact that we are human. The contemporary discourse of global citizenship is very much rooted in the discourse of globalization. The idea that the world is shrinking and increasingly interconnected economically, politically, and culturally.

Figure 1-1: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/continents-flags-silhouettes-mosna-1055960/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

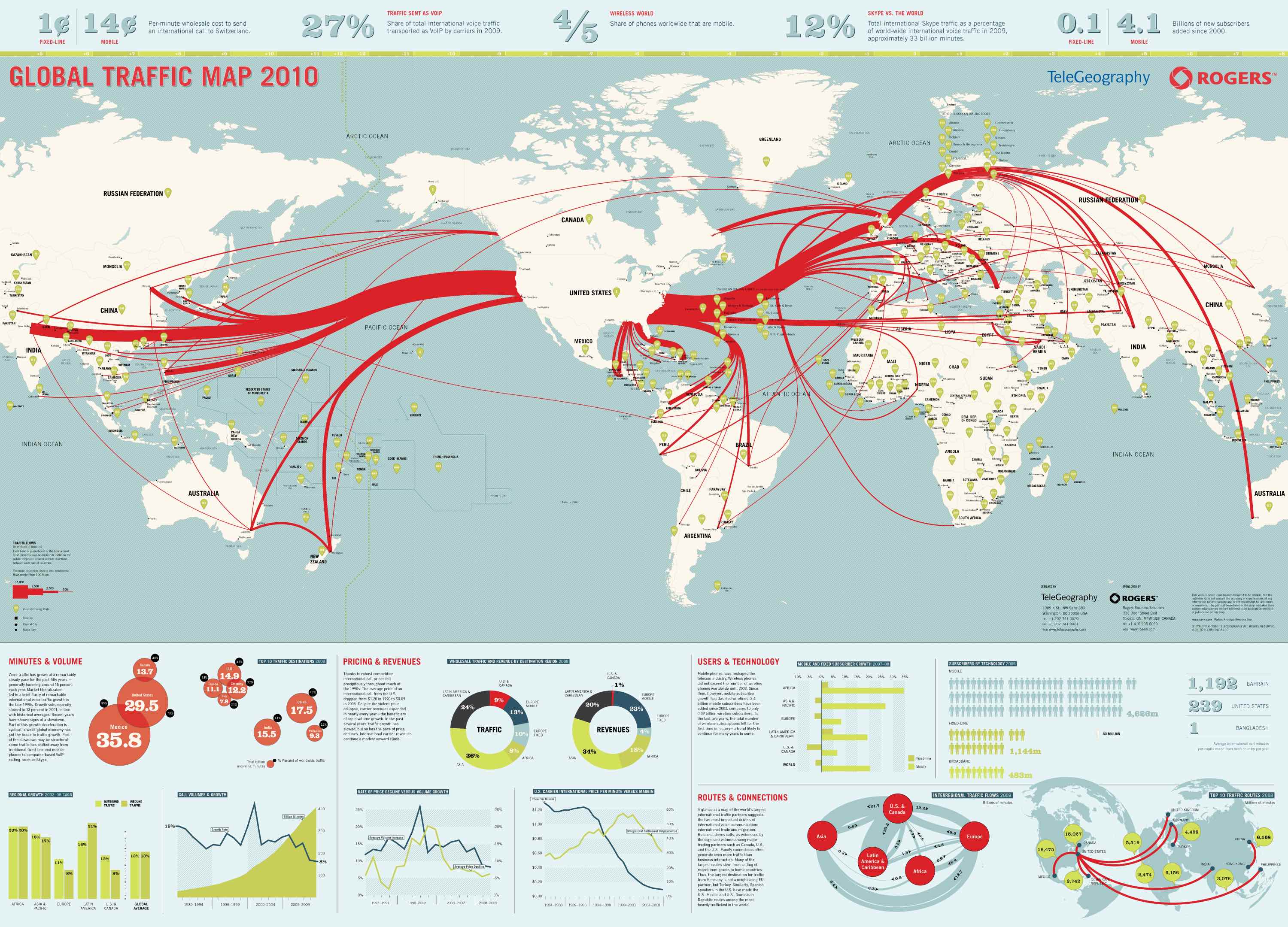

The positive narrative of globalization argues that international trade has made more goods available to more people at a sharply reduced cost; that international investment has lifted millions out of poverty; that international institutions have created frameworks to foster peace, promote international law, and support human rights; that communication and transportation technologies have shrunk the world into the proverbial global village – that any person any where is a second away by cell phone or email and hours away by airplane.

Figure 1-2: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/hands-world-map-global-earth-600497/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Pubic Domain. Courtesy of stokpic.

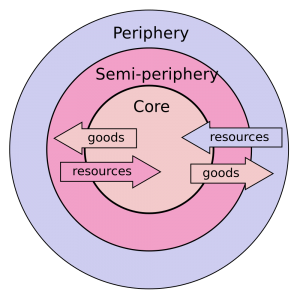

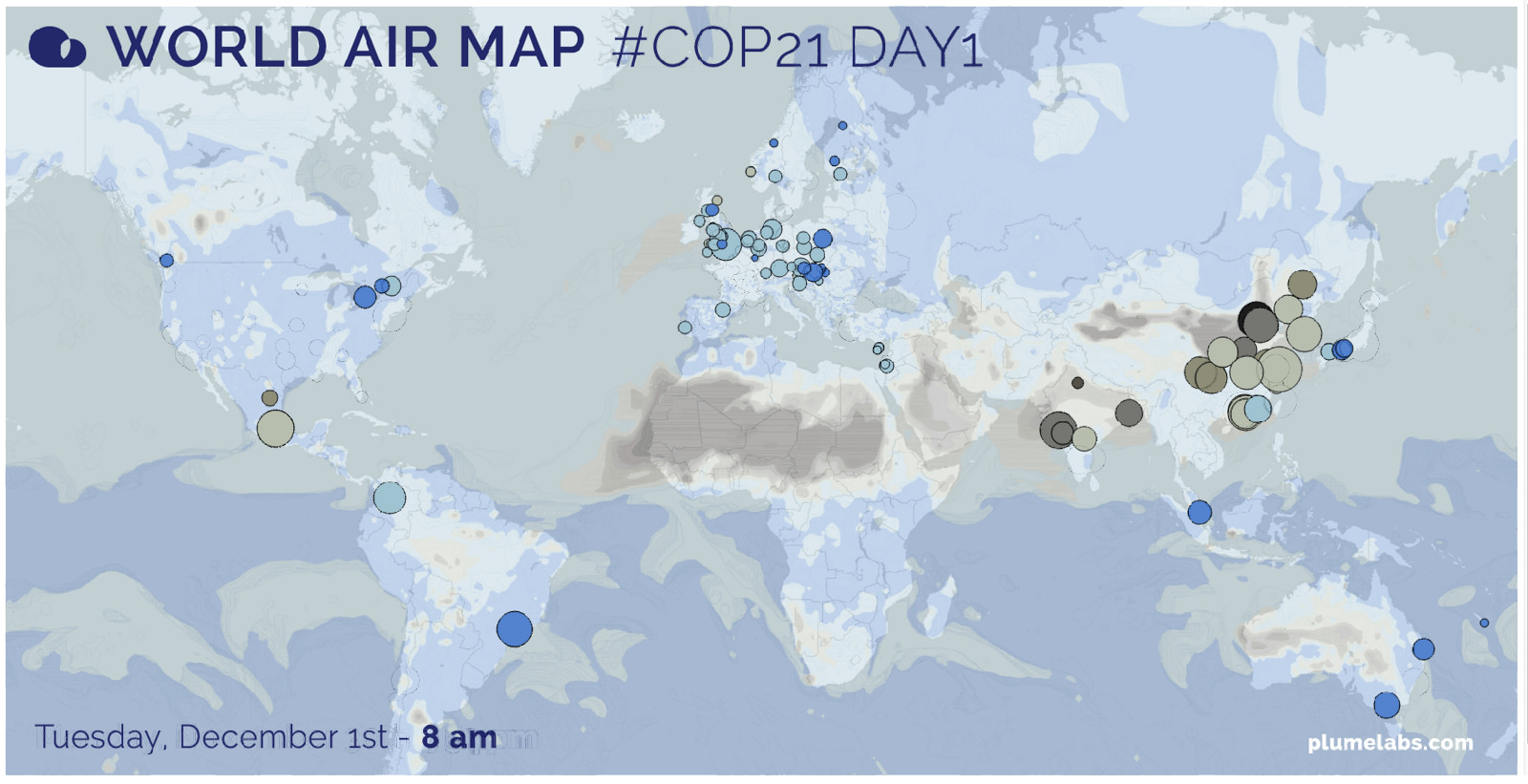

The negative narrative of globalization critiques this narrative, arguing that trade has reinforced imperial and colonial structures of dependency; that international investment allows multi-national corporations to exploit weaker regulatory frameworks to maximize profits to the detriment of labour; that international institutions establish norms and frameworks that claim universality put are in actuality constituted by particularistic European values; that the global village created by advances in transportation and communication technology has resulted in environmental degradation, international terrorism, and global crime syndicates.

Figure 1-3:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dependency_theory.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Wykis.

Figure 1-4:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_citizen_badge.svg#/media/File:World_citizen_badge.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of DasRakel.

For some, the impact and processes of globalization have led them to identify as ‘global citizens’. This identification might be rooted in their participation in international economics or business, such as Multinational Corporations. Or it may be driven by empathy for the plight of those seen suffering on people's laptops and TV screens – those fleeing war, famine, and persecution. Others may identify as global citizens in response to the externalities of globalization – climate change, environmental degradation, or exploitation. Cumulatively, these self-identified global citizens believe that they have responsibilities that transcend national borders. The more committed global citizens go further and argue that all people everywhere have universal rights by virtue of being human and that collectively we need to ensure everyone has access to these rights. Ultimately, those that identify as global citizens believe that they form part of an in-group, however ill-defined, and share a sense of global belonging that is just as real and just as meaningful as national belonging, religious belonging, or any other form of group identification.

However, many contest the reality of global citizenship. For some, 'global citizenship' is merely the conceit of the wealthy and the globally mobile. They argue some may identify as global citizens but in so doing they are merely another interest group advocating for the interests and values of the elite. For others, global citizenship is an aspiration that may be laudable but fails to meet any meaningful definition of ‘citizenship’. Citizenship infers an institutional basis which delineates and enforces rights and obligations. Critics question whether this exists at the global level. In sum, this course will introduce the narrative of global citizenship, critique the theoretical and practical aspects of it, and ask you to consider the value and practical importance of the concept.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Outline the difference between citizenship and global citizenship

- Discuss the main arguments in favour of global citizenship

- Discuss the main criticisms of global citizenship

- Read Israel, Ronald. “Global Citizenship: What does it mean to be a global citizen?” Kosmsos Spring/Summer 2012.

- Read Bowden, Brett. “The Perils of Global Citizenship” Citizenship Studies.

- Complete learning activity one

- Take the Quiz: http://together.akfc.ca/exhibit/en/global-development/take-the-global-citizen-quiz

- Read Byers, Michael. “Are You a ‘Global Citizen’?” The Tyee 2005.

- Complete learning activity two

- Watch the Hugh Evans’ Ted Talk “What does it mean to be a citizen of the world?” https://youtu.be/ODLg_00f9BE

- Complete learning activity three

- Watch the Intelligence Squared video “If You Believe You Are a Citizen of the World, You are a Citizen of Nowhere” https://www.intelligencesquared.com/events/if-you-believe-you-are-a-citizen-of-the-world-you-are-a-citizen-of-nowhere/

- Complete learning activity four

- Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- Empathy

- Empire

- Externalities

- Global citizenship

- Globalization

- Human rights

- Inherent rights

- International institutions

- International law

- International trade

- Legal concept of citizenship

- Legitimacy

- Privilege

- National borders

- Social dimension of citizenship

- Stateless people

- Structures of dependency

- Israel, Ronald. “Global Citizenship: What does it mean to be a global citizen?” Kosmos Spring/Summer 2012

- Bowden, Brett. “The Perils of Global Citizenship” Citizenship Studies, 7(3), 2003.

- Byers, Michael. “Are You a ‘Global Citizen’?” The Tyee, October 5, 2005

Learning Material

- Before moving on, let us assess what kind of ‘global citizen’ you might be

- Take the Quiz http://together.akfc.ca/exhibit/en/global-development/take-the-global-citizen-quiz

- Report your results in the poll below, we will return to these results in the discussion for this module.

Figure 1-5: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_arms_of_Canada_rendition.svg#/media/File:Coat_of_arms_of_Canada_rendition.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Jorge Compassio.

Figure 1-6: Kutupalong Refugee Camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. The camp is one of three, which house up to 300,000 Rohingya people fleeing inter-communal violence in Burma. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cox%27s_Bazaar_Refugee_Camp_(8539828824)_(cropped).jpg#/media/File:Cox%27s_Bazaar_Refugee_Camp_(8539828824)_(cropped).jpg Permission: Open Government Licence v1.0 Courtesy of Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

In order to meaningfully explore the concept of global citizenship, it is necessary to understand the constituent elements of the term. First, and most importantly, we need to examine the idea of citizenship. The legal concept of citizenship is employed in two primary ways. The first defines formal membership in a political community, most often within a state. This use of the term citizenship is roughly equivalent to nationality. For example, if you were born in Canada or have become naturalized here, you are a citizen of Canada or Canadian.

The opposite of a citizen is an alien. Aliens are either a citizen of another state, also known as a foreign national, or one of the 15 million stateless people in the world. Stateless people have no recognized citizenship in any state. People can become stateless for a variety of reasons, for example through conflict, gender bias, ethnic discrimination, or belonging to a non-state territory. The most recent example of a stateless people are the Rohingya, who are currently fleeing ethnic cleansing by the Myanmar government.

The second legal aspect of citizenship defines the rights and obligations between citizens and the state. In Canada, for example, citizens and permanent residents have protection under the law and constitutionally protected rights under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Charter protects democratic rights, language rights, equality rights, mobility rights, freedom of religion, freedom of expression, and freedom of assembly and association. However, it should be noted that permanent residents cannot vote, run for office, or gain employment in jobs that require a high-level security clearance. Citizenship also provides some protection and representation when citizens are traveling abroad through embassies and consular services. Conversely, citizenship also comes with obligations. In Canada, citizens are obligated to respect the law, the rights and freedoms of others, and there is an expectation citizen will participate in democratic processes. In other countries, there may be further obligations, such as military or community service. Some may even require declarations of loyalty to the state or traditional forms of authority like the monarchy. Therefore, from a legal perspective, citizenship is very much a concrete relationship between institutions and people, with clearly defined roles for each.

Figure 1-7:

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/95/Diagram_of_citizenship.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Cbowsie.

Figure 1-8: Source: https://flic.kr/p/qZgRz5 Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Rikki’s Refuge.

However, with the development and maturation of the welfare state, which emerged post-World War Two, a social dimension of citizenship has emerged that goes beyond the legal and political rights mentioned above. For some, citizenship stakes a claim on the right to a standard of living within the political community. In other words, the state has some obligation to ensure that citizens have access to things such as adequate housing, food, and education. Some make stronger claims that the state has an obligation to ensure an equitable distribution of resources between citizens. While the social dimension of global citizenship is more contested, it is still rooted in a concrete relationship between institutions and people.

So, what happens when we add the qualifier ‘global’ to the concept of citizenship? Well, let us apply the same legal and social perspectives introduced above. From a legal perspective, we introduced two aspects of global citizenship: membership in a particular community and the rights/obligation that are constitutive of that membership. There are two quite divergent views here: global citizenship is either defined as a universal membership of all people or a particularistic membership of people who live, work, and play at the global level. Consequently, the rights and obligations associated with global citizenship are also quite divergent. If global citizenship is defined as membership in a fellowship of all people, the rights and obligations of membership are connected, however loosely, to the narrative of universal rights. The idea that every person on the planet is owed certain inalienable rights from the simple fact of being born a human being. This also comes with an obligation, albeit less well defined, to ensure that others are able to benefit from the same universal rights.

Figure 1-9: Source: https://flic.kr/p/aSLahV Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of UN Geneva.

Figure 1-10: Source: https://flic.kr/p/62F8pE Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of sdobie.

If global citizenship is defined by membership in the limited group of people who work and/or live at the global level, it is less clear what rights and obligations are at play here beyond privilege: economic privilege which grants the means to be a global citizen and political privilege which allows access to decision-makers to support the interests of the global citizenry. From a social perspective, a similar division exists between those who see global citizenship as defined by membership in a global elite and those who define it as a universal fellowship of all people.

For those who define global citizenship through a universal membership, it is argued that all people in all countries have a right to their basic needs being met. In an almost teleological way, it is argued that the rights and obligations of citizens in the wealthiest states can and should be extended to everyone, everywhere. Further, it is argued that institutions, states, and even individuals have some obligation to ensure these needs are being met everywhere. When global citizenship is defined by membership in the global elite, the social aspect is a bit different. From this perspective, global citizenship is rooted in a deterritorialization of identity, norms, and values. It looks to universality, but a universality rooted in liberal internationalism and despite protestations to the contrary, is often accessible to only a privileged few.

These are issues we will return to both later in this module and throughout the course. Now, having contrasted the concept of citizenship to that of global citizenship, we are going to introduce the explicit argument made by/for global citizens and subsequently explore the criticisms made against them.

- Read “Are You a ‘Global Citizen’? Really? What does that mean?” by Michael Byers https://thetyee.ca/Views/2005/10/05/globalcitizen/

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal:

- What are the differences between national citizenship and global citizenship?

- What are the divergent definitions of ‘global citizenship’ identified in the article?

- To what degree is the concept of global citizenship linked to global capitalism?

- To what degree is the concept of global citizenship linked to collective responsibility?

- To what degree has the concept of global citizenship been co-opted by a narrow sub-section of socially progressive-minded but deeply privileged citizens of the global north?

- How can we ‘take back global citizenship’ as Prof Byer suggests?

Figure 1-11: Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:The_universal_declaration_of_human_rights_10_December_1948.jpg#/media/File:The_universal_declaration_of_human_rights_10_December_1948.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of UN-United Nations Department of Pubic Information.

Figure 1-12: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:My_Lai_massacre.jpg#/media/File:My_Lai_massacre.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Roland L. Haeberle.

Despite the seemingly contemporary nature of debates on global citizenship, it is nothing new. The ancient Greeks and Romans self-identified as global citizens as far back as 2500 years ago. Since then, global citizenship has been a recurring theme in philosophical debates. These debates have focused on the degree to which individuals have reciprocal rights and obligations with others: from family through to all of humanity. One of the most important questions postulated is whether we as individuals are obligated to treat people we have never met and who live on the other side of the world the same as our kith and kin?

While these debates are again nothing new, they have been made more urgent and more personal by the contemporary forces of globalization. Information and communication technology has brought the plight of the ‘other’ into our daily lives. Conflict and war were one thing when valorized and mythologized by our elders and leaders. It was quite a different thing to see the pictures and film coming out of the Vietnam War or Iraq War: war stories are very different than witnessing the suffering and brutality being both experienced and inflicted in war.

Advances in transportation have facilitated an exponential growth in the movement of people. This includes both those in the developed world utilizing cheap flights to go on vacation and those in the developing world fleeing conflict and persecution as well as seeking greater economic opportunity. This movement of people has made the ‘other’ more familiar. These are no longer places we have never been nor people we have never met – they are increasingly the people who live beside us or the people we have met while traveling abroad.

Figure 1-13: Source: http://faculty.georgetown.edu/irvinem/CCTP748/Internet-Mediology.html Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 US Courtesy of Martin Irvine.

The interconnectedness of international trade and finance has created both economic opportunity and costs. Opportunities include new markets to sell goods, access to cheaper resources, as well as new sources of finance. Costs include downward pressure on wages and significant challenges to less competitive industries both in the developed and developing world. The processes and outcomes of globalization have generated new international threats which require global responses. These threats range from transnational terrorism, think of Al Qaeda or ISIS; international financial crises/contagion, think of the Latin American Debt Crisis in the 1980s, the 1997 Asian Currency Crisis, or the 2008 Global Financial Crisis; environmental pollution, think ocean pollution, air pollution, or even the nuclear contamination of Chernobyl or Fukushima; climate change, think of global warming with its changing patterns of droughts/floods and increasingly dangerous and common hurricanes/typhoons.

Figure 1-14: Source: https://flic.kr/p/BUqhwo Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Strom-Report.

For many people, all of this has generated greater empathy and awareness of our common humanity and common interests. In turn, such empathy and awareness have fostered a nascent community of globally-minded people. At the thickest end of this argument, are people whose commitment to the global community challenges or even eclipses all others. If we begin to identify with the global community, we begin to admit to responsibilities that extend past our national borders. We begin to build ties between like-minded people. We begin to think and act globally. This process has promoted the cultivation of shared values that have coalesced around human rights, environmental protection, gender rights, multiculturalism, poverty alleviation, conflict mitigation, eliminating weapons of mass destruction, democratic governance, and the protection/preservation of world culture to name but a few. These values have both created and in turn been supported by the emergence of international institutions and civil society networks. These institutions and networks have fostered norms, standards, and laws that further strengthen the sinews of globalization and global citizenship. In some ways, global citizens are seen as the necessary corollary to multinational corporations and international institutions in that they are the countervailing force to business and politics. However, even those who identify the strongest with the concept of global citizenship, recognize its fragility. They recognize that global citizenship is very much a project that requires leadership and activism. They recognize that the narrative of global citizenship is still under-defined, and the endpoint is still unknown. They recognize that the project of global citizenship is like a house of cards that could all come tumbling down even while at the same time they strongly believe it is a necessity in our globalized world.

- Watch the Hugh Evans’ Ted Talk “What does it mean to be a citizen of the world?”

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal:

- Who are Davinia and Sonny boy?

- Why are they significant to Evans?

- Why does Evans argue campaigns like ‘Make Poverty History’ are not the answer?

- What does he suggest is perhaps the answer?

- Evans describes the story of presenting his ideas to Australian Foreign Affairs Minister Alexander Downer. Downer suggests that no one really cares about foreign aid and that the only thing that matters is taking care of their own.

- Evans and Downer posit polar opposite positions on our responsibilities both individually and collectively at the global level.

- What are the relative strengths and weaknesses of each position?

- Which position do you agree with the most?

- Who are Davinia and Sonny boy?

Figure 1-15: Source: https://flic.kr/p/7DGB9C Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Duncan Rawlinson – Duncan.co – @thelastminute.

The narrative of global citizenship makes extraordinary claims. It argues that we as individuals have obligations beyond our families, our cities, our religious associations, our ethnicities, and our countries. These obligations are based on ethical claims of universal human rights. They are based on the necessity of dealing with the pressing externalities of our globalized world. The narrative of global citizenship and the obligations that come with it are demanding great transformation. They are all-encompassing. As such, they also raise numerous critiques. The first criticism argues the basis of global citizenship is often fundamentally flawed. Whether it is the Ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes or the contemporary political philosopher Martha Nussbaum, advocates of global citizenship privilege the global community over nationality. They both argue that the place of one’s birth is accidental and morally irrelevant and as such any obligations derived from national citizenship are arbitrary. Further, they argue that a much more ethically consistent claim can be made on our obligation to all humans. There is nothing arbitrary about being human. Critics of this position argue that both Diogenes and Nussbaum are missing the rich social and cultural histories that give meaning to particular societies. This meaning generates attachment to community and builds thick identities to which individuals are willing to make sacrifices in the name of. They argue that global citizenship is too broad, too theoretical, too antiseptic, to generate such loyalty and willingness to sacrifice.

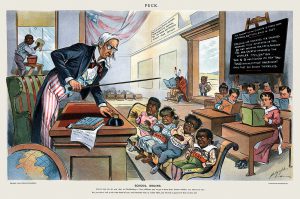

Figure 1-16: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:School_Begins_(Puck_Magazine_1-25-1899).jpg#/media/File:School_Begins_(Puck_Magazine_1-25-1899).jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Louis Dalrymple.

The second criticism of global citizenship questions the use of the word ‘global’. It is often assumed that the term global is used spatially, to define the geographical reach of citizenship. In his sense, ‘global’ is a value-neutral term. However, some question this neutrality. Whether it is the Ancient Greeks and Romans or contemporary liberal philosophers, the word ‘global’ refers to an order defined by the values of the dominant actor or culture. It refers to the expansion of an empire, whether that be literal in the sense of the Romans or a more figurative sense such as the contemporary liberal democratic capitalism. The rights and obligations of membership in the global community are neither neutral nor a product of negotiation between equals. They are imposed by the strong at the core of the system. From this perspective, becoming a global citizen is less about building or recognizing a world community than it is about being allowed to join a club whose rules are already established. If this argument that global citizenship is about membership in an empire, then it is not benign. The rights and obligations that are associated with global citizenship will privilege the core at the expense of the periphery.

Figure 1-17: Source: https://flic.kr/p/iqq9Le Permission: CC BY 2.0 courtesy of barbinviaggio.

The third criticism of global citizenship has a bit more of a hard edge to it: global citizenship is hypocrisy. They argue that most self-identified global citizens are keyboard warriors: they ‘like’ a post on their Facebook feed that details the suffering of people ‘over there’; they attend live aid concerts and say they went to bring attention to the plight of ‘those people’; they wear some fashionable wrist band in support of poverty alleviation or anti-corruption. They do not organize political movements to force their government to act on specific issues. They do not volunteer more than a token bit of their time and money to help others. They do not take the time to meet and know the lived experiences of those they are advocating on behalf of. And perhaps most telling, they will most likely be able to describe the plight of people across the world but would have little idea about the poverty in their own cities. Those who argue that global citizenship is largely hypocritical posit that it is easier to act in a token way on behalf of people you have never met, in places you will likely never go than it is to do the hard work necessary to solve similar problems right in front of us. In this way, global citizenship is more about privilege and making the privileged feel good about themselves than it is about fighting for the rights and obligations of humanity.

Figure 1-18: Source: https://flic.kr/p/zDqZzG Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Mike Gifford.

The last criticism is much more forgiving. It argues that while people may be genuinely globally minded and that such global awareness is increasingly necessary, it is wrong to use the term citizenship. Citizenship denotes an institutional arrangement with established and reciprocal rights and obligations. If I am Canadian, I have established and reciprocal rights and obligations with the Canadian government. Most are written down and defined in the Constitution and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The rest are conventions that have evolved through practice but are still generally recognized by myself and fellow citizens. But what institutional arrangement exists globally? There is no world government or authority to whom I have defined and reciprocal rights and obligations. So, what does it mean to be a global ‘citizen’? Does the concept of citizenship have any meaning in this context? Another variant of this critique may concede the necessity of acting globally to attenuate global problems. It may recognize the benefit of empathizing with the plight of others. But national citizenship has one major advantage over global citizenship, legitimacy. The rights and obligations that are created in the national context are legitimated by the authority of the state. In Canada, the authority of the state is legitimated by its democratic processes. This, in turn, legitimates the rights and obligations that constitute Canadian citizenship.

But by what means are the ill-defined rights and obligations of global citizenship defined? What actor has the power, authority, and legitimacy to draft, implement, and enforce such rights and obligations? However, with that being said, most will concede that there is something to the idea of global citizenship. Many might even concede that those who identify as global citizens are making a difference in addressing global issues. But for the critics of global citizenship, these are important questions that need to be addressed before the concept can have much practical effect.

- Watch the Intelligence Squared video “If You Believe You Are a Citizen of the World, You are a Citizen of Nowhere”

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal:

- A distinction is made between two types of people:

- The people from somewhere – people whose sense of identity is rooted to a place and a group and therefore more closely associated with national citizenship

- The people from anywhere – people whose sense of identity is tied to achievement, position, and life experience and therefore more closely associated with global citizenship

- Is this a useful distinction?

- Why or why not?

- Is global citizenship a privilege of the elite?

- Do you agree with David Goodhart’s argument when he says the liberal elite have won most of the arguments in the past 30 years?

- Does this explain, at least in part, the current rise of populism?

- Can global citizenship be as real to individuals as national citizenship?

- Do you think we can have multiple identities?

- Think of the analogy that Elif Shafak introduced: that we are like a compass with one leg firmly rooted in the particular and the other leg tracing a wide circle in a number of other communities.

- Do you agree with Simon Schama’s argument that the rights and obligations are derived from the identity of global citizenship rather than concrete institutions? Link this back to the distinction between people from anywhere vs people from somewhere.

- Was there a particular quote or comment that resonated with you? Why?

- A distinction is made between two types of people:

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Charter of Rights and Freedoms: is an important document in providing all citizens with constitutionally protected rights. The Charter protects democratic rights, language rights, equality rights, mobility rights, freedom of religion, freedom of expression, and freedom of assembly and association.

Empathy: is the ability to understand what others are going through and share those feelings.

Empire: is a group of countries or territories that are ruled by a single sovereign authority and constitute a major political unit. Such political organizations concentrate political, economic, and social power in the metropole to rule over the periphery. The term can also used in a figurative sense to describe a dominant ideology or political/economic system that mimics a traditional empire.

Externalities: are the positive or negative consequences of economic activity that are experienced by unconnected third parties.

Global citizenship: is the idea that the rights and obligations of human beings extend beyond national borders. It is further argued that we are part of a global community with inherent rights and obligations owed to each other by the fact that we are human.

Globalization: is the idea that the world is increasingly interconnected economically, politically, and culturally. An important result of globalization is that the actions/policies in one part of the world have direct consequences for actors around the world.

Human rights: are the basic rights and freedoms that every human being possesses from birth until death and apply irrespective of where one is from, what they believe or how they choose to live their lives.

Inherent rights: are fundamental rights that are guaranteed to everyone by virtue of being born human.

International institutions: are organizations that facilitate cooperation by drawing members from at least 3 states which are bound by a formal agreement. They function through organizational structures and are set up to achieve specific purposes and mandates.

International law: is the system of legal rules that govern the interaction of sovereign states. It also includes the laws governing the interactions of the citizens and businesses of sovereign states to their counterparts in other sovereign states and the rights and duties.

International trade: is the exchange of goods and services between countries and which contributes to the world economy. The prices are determined by supply and demand which in turn are influenced by global events.

Legitimacy: is the perception by the citizens that their leaders and institutions have the authority and right to govern over them and are acting in their best interest.

Privilege: is a special right, advantage, or immunity granted or available only to a particular person or group of people. In the narrative of global citizenship, this often refers to the privilege available to the global elite.

National borders: are physical demarcations and boundaries that separate the territories of sovereign states.

Stateless people: are those who have no recognized citizenship in any state. This can occur for a variety of reasons, including conflict, gender bias, ethnic discrimination, or belonging to a non-state territory.

Structures of dependency: are ways in which the world economy is shaped to favor some states, businesses or individuals to the detriment of others. It is the advancement of an economy that is conditioned on the limiting the development possibilities of the subordinated economy.

Legal concept of citizenship: is the legal status of one enjoying the benefits of belonging to a political community and the reciprocal duties and obligations owed between citizens and the state.

References

Armstrong, Chris. "Global Civil Society and the Question of Global Citizenship." Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 17, no. 4 (2006): 348-56.

Briddle, James. “The Rise of Virtual Citizenship”. The Atlantic. Last modified February 21, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/02/virtual- citizenship-for-sale/553733/

Business Dictionary. International Law. Accessed September 15, 2018. http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/international-law.html

Byers, Michael. “Are You a ‘Global Citizen’?”. The Tyee. Last modified October 5, 2005. https://thetyee.ca/Views/2005/10/05/globalcitizen/

Calhoun, Craig. Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Cane, Peter and Conaghan, Joanne. The New Oxford Companion to Law. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Dobbs, Leo and Morel, Haude. “Q&A: The World’s 15 Million Stateless People Need Help”. The UN Refugee Agency. Last modified May 18, 2007. http://www.unhcr.org/news/latest/2007/5/464dca3c4/qa-worlds-15-million- stateless-people-need-help.html

Duhaime’s Law Dictionary. Citizenship. Accessed September 15, 2018. http://www.duhaime.org/LegalDictionary/C/Citizenship.aspx

Duyvendak, Jan Willem, Geschiere, Peter, Editor, and Tonkens, Evelina Hendrika, Editor. The Culturalization of Citizenship : Belonging and Polarization in a Globalizing World. 2016.

Equality and Human Rights Commission. 2018. Human Rights. May 24. Accessed September 15, 2018. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/human-rights/what-are-human-rights

Ferraro, Vincent. 2008. "Dependency Theory: An Introduction." In The Development Economics Reader, by Giorgio Secondi, 58-64. London: Routledge

Frost, Michael. “People from Somewhere vs People from Anywhere”. Mike Frost. Last modified July 29, 2017. https://mikefrost.net/people-somewhere-vs-people- anywhere/

Goodhart, David. The Road to Somewhere : The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics. 2017.

Government of Canada. “Understand Permanent Resident Status”. Government of Canada. Last modified December 13, 2017. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/new- immigrants/pr-card/understand-pr-status.html

Hallowell, Gerald. The Oxford Companion to Canadian History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Ian Hurd. 2007. Legitimacy. Accessed September 15, 2018. https://pesd.princeton.edu/?q=node/255

Karen Mingst. 2018. International Organizations. Accessed September 15, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/topic/international-organization

Ream Heakal. 2018. What is International Trade? January 12. Accessed September 15, 2018. https://www.investopedia.com/insights/what-is-international-trade/

Scott, John. A Dictionary of Sociology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Shiblak, Abbas. “Stateless Palestinians”. Forced Migration Review. Last modified August, 2006. http://www.fmreview.org/palestine/shiblak%20

Smith, Nicola and Krol, Charlotte. “Who are the Rohingya Muslims? The Stateless Minority Fleeing Violence in Burma. The Telegraph. Last modified September 19, 2017. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/0/rohingya-muslims/

Taylor, Paul. “How Britain Made Me a Citizen of Nowhere”. Politico. Last modified May 16, 2018. https://www.politico.eu/article/how-britain-made-me-a-citizen-of- nowhere/

The Law Dictionary. 2016. Inherent Rights. Accessed September 15, 2018. https://dictionary.thelaw.com/inherent-right/

“The Benefits and Obligations of Being a Permanent Resident of Canada”. Immigration.ca. Last modified 2018. https://www.immigration.ca/benefits- obligations-permanent-resident-canada/