Overview

Figure 2-1:

Source: https://pixabay.com/en/network-earth-block-chain-globe-3537401/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain

In the last module, we looked specifically at the idea of global citizenship. We first looked at the idea of citizenship, both legally and socially. We noted that it is defined by a concrete relationship between individuals and some institutional structure, most often the state. This relationship sets out the reciprocal rights and obligations between citizens and the state. In Canada, for example, citizens have constitutionally protected rights and freedoms while also having obligations to act lawfully and expectations of participating in democratic processes. Further, with the advent of the welfare state, there is a requirement to pay taxes, and in return, the state is expected to ensure some minimum standard of living for all citizens. Building on this discussion, we then ask what it means to be a ‘global’ citizen? Is there a similar institutional structure? With an explicit set of reciprocal rights and obligations? The answer is… well, not really. Yet, at the same time, it is noted that some people do identify as global citizens. It is noted that there are global issues that seem to require some degree of global solidarity. It is noted some argue that we require some form of global citizenship even if the concrete nature of the relationship lacks clear definition. In this module, we will give some theoretical structure to this debate. Two broad positions will be introduced that are at the heart of this debate: communitarianism and cosmopolitanism. Before doing so however, we will build on the argument introduced in our course reading ‘Debating Globalization: cosmopolitanism and communitarianism as political ideologies’ by Zürn and de Wilde. They posit four main issues that inform the debate between advocates for global citizenship and their critics: the permeability of borders, the appropriate locus of authority, the normative value of community, and their respective claims on justice. From this, we will have provided a more robust theoretical position to interrogate the coherence and practical effect of global citizenship as a concept.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

1. Outline the four issues at the core of globalization debates: the permeability of borders, the appropriate locus of authority, the normative value of community, and their respective claims on justice.

2. Apply the concept of cosmopolitanism to global politics

3. Apply the concept of communitarianism to global politics

1. Read Wilde, Pieter de and Zürn, Micheal. “Debating globalization: cosmopolitanism and communitarianism as political ideologies” Journal of Political Ideologies, 2016

2. Complete learning activity one

3. Take the Abacus Quiz http://abacusdata.ca/globalism_nationalist_quiz/

4. Watch the Ted Dialogue ‘Nationalism vs Globalism: the new political divide’ https://youtu.be/szt7f5NmE9E

5. Complete learning activity two

6. Watch the Talk to Aljazeera video “The case for cosmopolitanism” by Kwame Anthony Appiah https://youtu.be/-STy99EU-4I

7. Complete learning activity three

8. Read Fareed Zakaria’s article in Slate ‘The ABCs of Communitarianism’

9. Complete learning activity four

Anarchical

Authority

Categorical imperative

Civil society

Communitarianism

Cosmopolitanism

Cultural products

Community

Extreme poverty

Globalism

Hard borders

Inequality

International organizations

Justice

Moderate cosmopolitanism

Non-Governmental Organizations

Normative

Original position

Permeability of borders

Primordial

Sovereignty

Straw man argument

Strict cosmopolitanism

Supranational

The common good

The good life

Veil of ignorance

World state

1. Wilde, Pieter de and Zürn, Micheal. “Debating globalization: cosmopolitanism and communitarianism as political ideologies” Journal of Political Ideologies, 2016

2. Zakaria, Fareed. 1996. The ABCs of Communitarianism. July 26 . Accessed September 30, 2018. http://www.slate.com/articles/briefing/articles/1996/07/the_abcs_of_communitarianism.html.

Learning Material

Figure 2-2:

Source: https://flic.kr/p/DrnQ5Y Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Peg Hunter.

If we are going to have a meaningful discussion of the conceptual coherence and practical effect of ‘global citizenship’, we need to look more deeply into the theoretical debates upon which the concept rests. The debates for and against global citizenship are nothing new, as we noted in module one. In the fields of philosophy and politics, these debates have raged from the time of Greek city-states through to contemporary debates on globalization. Through all of this, similar questions are consistently asked: Are my rights and obligations restricted to my family? My city? My state? My fellow human beings? Connected to such interrogations are questions of community: to whom do I have fellowship? Who is the ‘other’? What demarcates the inside from outside? Is there a sharp division between the inside and outside or do I have a range of rights/responsibilities that extend from my immediate family to all of humanity? Who establishes the rights and obligations of the communities that I belong to? By what legitimate authority are such rights and obligations established?

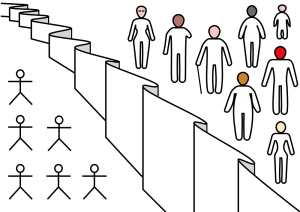

Figure 2-3:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Original_Position.svg#/media/File:Original_Position.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Courtesy of Philosophyink.

Many interesting thought experiments have emerged from such debates. Consider John Rawls’ idea of the ‘original position’ whereby the rights and obligations of society are arrived at behind the ‘veil of ignorance’. He argues that if we were to decide on the rules of society not knowing what position we would ultimately occupy in that society, we will tend towards more equality. We will make rules which mitigate the risk of being one of the most vulnerable members of that society. This resonates with Immanuel Kant’s ‘categorical imperative’ whereby moral principles are argued to be absolute and not dependent on ulterior motives.

These are intriguing ideas that force us to confront our own biases; to confront why we are willing to allow the lottery of life to decide who is privileged and who is disadvantaged; to confront why we justify the sacrifice of some for the greater good. However, these debates have for the most part remained the providence of philosophical discussions. Practical political debates, on the other hand, are much more likely to focus on questions of citizenship, the state, and the nexus between power, authority, and legitimacy. However, many argue the force of contemporary economic, political, and cultural globalization requires us to move beyond thought experiments and philosophical debates. It is argued that we need a more robust engagement with the practical and political implications of rights and obligations at the global level. And that is the objective of this module: to explore the theoretical foundations that underpin much of the debates on global citizenship. We will begin by looking at four contentious issues that frame much of the debates on globalization and, by extension, global citizenship: the permeability of borders, the appropriate locus of authority, the normative value of community, and their respective claims on justice. Next, we will look at the two positions that emerge from this: cosmopolitanism and communitarianism.

- Before moving on, let us assess whether you are a globalist or a nationalist

- Take the Cosmopolitanism versus Communitarianism Quiz

- On the live poll app, indicate whether you identify as a ‘Strong Cosmopolitan’, ‘Weak Cosmopolitan’, ‘Weak Communitarian’, ‘Strong Communitarian’, or ‘Ambivalent’.

Figure 2-4: The Rhodes Colossus Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Punch_Rhodes_Colossus.png#/media/File:Punch_Rhodes_Colossus.pngPermission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Edward Linley Sambourne.

Figure 2-5: Space Tourist Mark Shuttleworth. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mark_Shuttleworth_NASA.jpg#/media/File:Mark_Shuttleworth_NASA.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of NASA.

There is little debate that quantitatively globalization is a reality: the world is more interconnected and interdependent than ever before. In terms of communication and transportation technology, the world has become smaller. Places that seemed exotic and remote 30 or 40 years ago have now become routine destinations for backpackers and even family vacationers. Today’s wealthy explorers now speak of traveling to outer space as their predecessors spoke of traveling from Europe to Asia, Africa, or Latin America 200 years ago.

Migration has become less alienating with cheap flights to visit home and advances in telecommunication allowing families to stay connected through video chats and cell phone calls. In terms of economics, global supply chains and multinational corporations have brought new products at lower prices to more people than ever before. The percentage of those living in extreme poverty has been sharply reduced albeit with a commensurate increase in inequality both in and between states.

Goals Politically, we have seen the rise of an increasingly dense set of international organizations and networks that have sought to coordinate the implications of globalization. Some are universal, like the United Nations (UN) or the World Trade Organization (WTO). Others are regional, like the European Union (EU), Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), or Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Some represent specific interest areas, like the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Beyond state-based organizations, we have also seen the rise of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) like Oxfam or Greenpeace that seek to represent civil society groups. Culturally, we have seen the diffusion of ideas, meanings, and values around the globe. This can occur by personal contact

Figure 2-6: Millennium Development. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MDGs.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of United Nations.

through travel and migration or the explicit packaging, sale, and consumption of cultural products like books, tv, music, video games, and movies. Hollywood blockbusters can be seen in almost every country in the world while Bollywood and Anime are reversing the flow of cultural exports back to the West.

However, while it is generally agreed that globalization is a quantifiable fact, there is less agreement on whether this is a good thing, whether the benefits outweigh the costs. For proponents, globalization represents a positive narrative of economic opportunity, of the opportunity to realize universal human rights, and of the potential to transcend a world-history defined by environmental degradation, conflict, colonialism, and imperialism. For opponents, globalization represents a negative narrative of economic coercion, threats to the values of particular communities, and new forms of economic, political, and cultural imperialism.

In order to make sense of these two opposing positions, it is useful to look at four conflicts that define their differences: the permeability of borders, the appropriate locus of authority, the normative value of community, and their respective claims on justice.

( Figure 2-7: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/flag-geneva-un-3369978/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of konfernezadhs. Figure 2-8: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/adult-african-african-american-3641205/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of rawpixel. Figure 2-9: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/hollywood-sign-los-angeles-hollywood-1598473/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of 12019. Figure 2-10: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/bollywood-movie-cinema-india-1687410/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Tumisu. Figure 2-11: A world of individuals. Source: https://pixabay.com/en/social-media-faces-photo-album-550767/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt. Figure 2-12: A world of Borders (Korean DMZ). Source: https://flic.kr/p/7u7VhQ Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of james Cridland. )

Permeability of Borders

Figure 2-13: San Diego (Right) versus Tijuana (Left). Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Border_USA_Mexico.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of U.S. Military.

A key distinction between the proponents and opponents of globalization starts with the permeability of borders. Proponents of globalization note that hard borders both reduce international opportunities and hamper efforts to attenuate the growing list of problems that transcend national borders. Hard borders make the free movement of goods, capital, finance, and labour more difficult. They make national, regional, and global economies less efficient. They raise the cost and reduce the availability of basic goods for the poorest citizens in every state. They reduce the ability of states to meaningfully deal with dire threats, including the environmental degradation of our planet; the implications of global climate change; the financing and operation of global terrorist networks; the trafficking of humans and drugs by global crime syndicates; the integrity and security of our global communication and transportation technologies; and the ability to respond to both man-made and natural disasters, to name a few. Opponents to globalization argue that permeable borders may present opportunities for the 1% of the world’s economic, political, and cultural elite. However, for the mass majority of the people in the world, it is borders that offer protection. From this perspective, permeable borders are a threat to local labour conditions, democratic accountability, and the state’s ability to fend off much wealthier and potentially more powerful actors including other states and MNCs. However, perhaps most powerfully, opponents of globalization see borders as a protection of their history, culture, values, norms, and agency.

The Locus of Authority

Figure 2-14: UN Security Council. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Barack_Obama_chairs_a_United_Nations_Security_Council_meeting.jpg#/media/File:Barack_Obama_chairs_a_United_Nations_Security_Council_meeting.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Peter Souza.

A second point of contention between the proponents and opponents of globalization focuses on the appropriate locus of political authority. Opponents to globalization rightfully assert that there is no legitimate political authority above the state. For any such authority to legitimately exist above the state would require some form of institutional arrangement based on the consent of those being governed. The strongest opponents to any form of supranational political authority suggest that attempts to form a meaningful global polity would be impossible. They argue that such a polity would be so large and so diverse that legitimacy based on participation would be meaningless – what is one person or one vote when counted amongst seven billion people. Further, given the preponderance of power in the make-up of current political institutions at the global level, it is highly unlikely that one vote would be given equal weight between the strong and the weak. Consider the current weighted voting of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. The Western Developed states hold 57% of the votes, with the US alone holding 17%, compared to the 29% held by the poorest 165 states. This weighted voting has also resulted in an informal gentleman’s agreement that the IMF would always be led by a European and the World Bank always be led by an American. Conversely, proponents of globalization argue that the increasingly integrated nature of the world necessitates empowerment of governance beyond the nation-state. It is argued that the world has in many ways outgrown the limits of national sovereignty and requires a global polity. They highlight the way MNCs shift labour, capital, and their national headquarters in order to maximize profits without any political authority to constrain them: Walmart, for example, constitutes the world’s 10th largest economy, just after Canada. Beyond MNCs, globalists argue that the state itself may be a source of threat. They point to the actions of the Myanmar government’s attempt to ethnically cleanse the Rohingya or the state’s role in the Rwandan genocide. While proponents of globalization agree that it is necessary to situate some form of political authority above the state, they don’t all agree on what form that should take: a world government or some form of multilateral decision-making structure bound by international law.

The Normative Value of Community

Figure 2-15: Source: https://flic.kr/p/pF6tHQ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Lawrence OP.

The third issue that divides the proponents and opponents of globalization is the normative value of community. For some opponents of globalization, the state is the highest possible form of community. They argue that any attempt to constitute community beyond the state is doomed to fail. Such a construct is simply too big and, more importantly, lacks enough shared sense of belonging to maintain itself. The current struggles of the European Union are often cited as an example of trying to establish political authority above the state. Rather, the opponents of globalization argue the state is the highest polity able to contain the history, values, and norms of a people. Ultimately, they argue, such community gives meaning to our lives individually and collectively. This position is refuted by the proponents of globalization. Instead, they argue the state and one’s belonging to the state is simply an accident of birth. We do not own our state’s past, we have not contributed to its glories nor are we responsible for its shame. The only community with more worth is the fellowship of all human beings – the universal community. Some may not go quite so far as this, instead of arguing our ‘community’ is constituted by concentric circles of belonging. We have the thickest bonds with our family, but we also have bonds that extend outwards to the universal community.

Justice

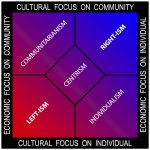

Figure 2-16:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Political-spectrum-multiaxis.png#/media/File:Political-spectrum-multiaxis.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Guðsþegn.

Finally, proponents and opponents of globalization disagree on the means of achieving or reinstating justice in our contemporary world. Proponents of globalization seek justice through the empowerment of individual rights; by removing restrictions on individual agency. They may disagree on what exactly to protect and exactly how to do it, but they agree progress is possible when individuals are able to act on their own self-interest with the necessary knowledge to inform such decision-making. Opponents of globalization argue that it is not possible to even define justice without reference to the values, beliefs, and norms of the community. This is not the freedom of the individual but rather the freedom of community self-determination; justice as the pursuit of the common good. By taking these four points of contention between the proponents and opponents of globalization together, two theoretical positions emerge: cosmopolitanism and communitarianism. We will detail these two positions in the proceeding two sections of this module.

- Watch the Ted Dialogue ‘Nationalism vs Globalism: the new political divide’

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What is the role that ‘story’ plays in making sense of our world?

- What has happened to the 20th-century story?

- Why have we seen a return of nationalism as part of our story?

- Why does Harari argue the story of nationalism will not work in our 21st-century globalized world?

- Why does he argue global issues like climate change requires additional loyalties and commitments beyond the nation?

- Why may technological innovation require a common global response?

- Harari argues that global forms of governance may not be democratic. He argues the future may not look like Denmark but rather Ancient China and that is ok. Do you agree that the need for global governance to solve global issues outweighs the need for it to be democratic?

- When Harari is asked by Adi-Dako from Ghana about the Western bias in global governance, Harari responds that it has been unjust. But that those who suffered in the past are most likely to suffer from contemporary global issues now and in the future and therefore should support global governance out of self-interest. Do you agree or disagree with this position?

- Harari closes with the idea that change and progress is historically connected to disruption, conflict, or even catastrophe. Given the tension between nationalism and globalism, what do you think the future looks like?

- What is the role that ‘story’ plays in making sense of our world?

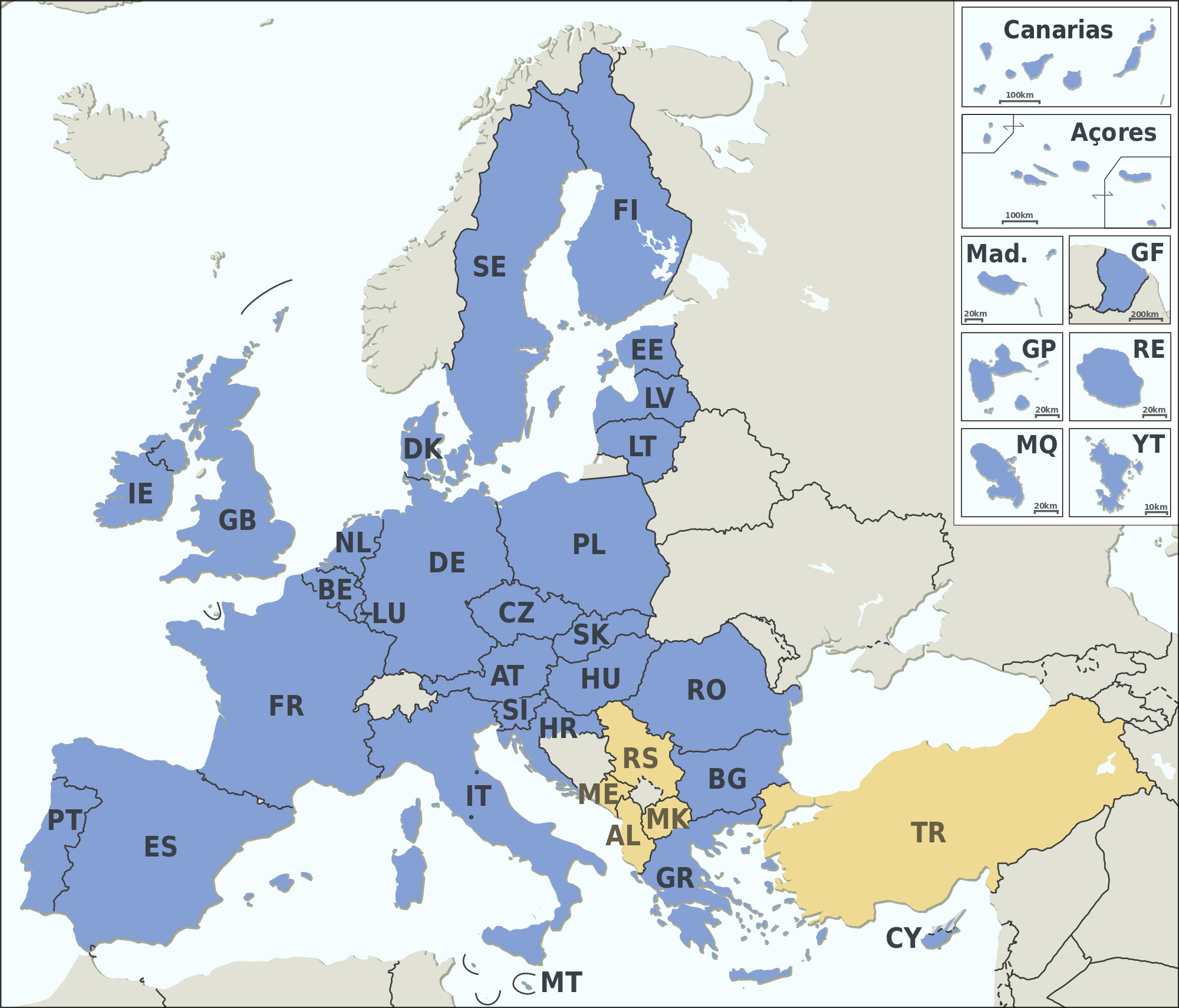

Figure 2-17: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EU_Member_states_and_Candidate_countries_map.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Alexrk2.

It may seem odd that we are starting with cosmopolitanism instead of communitarianism. Communitarianism is older, rooted in narratives of history and community, even to primordial claims on the importance of blood and soil. But in many ways, cosmopolitanism, or at least the rhetoric of cosmopolitanism, has become the norm. The idea of progress is equated with universal rights and the weakening of borders to allow the free movement of goods, finance, and people. In its most utopian form, cosmopolitanism is a story of overcoming conflict, overcoming inequality, and of empowering all peoples to achieve a meaningful life. But as we heard in the Ted Dialogue, there is a growing disconnect with globalism. It is argued that the story of globalism is bereft of particular meaning; that in trying to be everything to everybody, globalism lacks the deep attachment that motivates people to sacrifice for the general good. We will touch on this more extensively in the next section. But it important to note here, that this means that we are seeing a resurgence of communitarian ideas. To make sense of this new chronology, we are starting with cosmopolitanism rather than communitarianism.

To begin, it is important to note that contemporary cosmopolitanism as an ideological position is not homogenous. There are a number of distinct variants. For example, strict cosmopolitanism requires decisions to be made according to need and to strip away any preference or privilege associated with community. In other words, if your 10$ could help your child buy a pair of shoes without holes in the toe or feed 50 children in a conflict zone, the choice is clear: help the 50 children and thereby do the most good for the greatest number with the resources at your disposal. However, this is a pretty harsh metric and many would argue sets an unreasonable standard. Others advocate for a more moderate cosmopolitanism which argues we do have a duty to provide aid to those in need regardless of who they are or where they are from. But this moderate position also recognizes we have special duties and obligations to those closest to us. But we can use the four dividing lines introduced in the last section to find some commonalities that hold true for most variants of cosmopolitan thought. On the issue of border permeability, all variants of cosmopolitanism seek more openness regarding the movement of goods, finance, culture, and most importantly people. Stricter versions of cosmopolitanism reject borders at all. From this perspective, states and borders are without moral value as they simply reinforce the privilege of the elite. More moderate versions of cosmopolitanism accept the necessity of borders but advocate for more permeability. From this perspective, borders should only be as thick as is absolutely necessary. Think about the European Union, where the internal borders of the 28 member states have been removed but they can, and have been, put back in place when necessary.

Figure 2-19: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/hand-united-together-people-unity-1917895/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of truthseeker08.

Figure 2-18: UN General Assembly. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:UN_General_Assembly_hall.jpg#/media/File:UN_General_Assembly_hall.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Patrick Gruban.

On the issue of where political authority should reside, cosmopolitans argue that there must be some form of global polity based on their claims of universal community. Again, there is variance in the cosmopolitan school. Some advocate for a world government, that has the political authority to tackle issues that are transnational in nature – global environmental degradation, global crime syndicates, transnational terrorism, economic interdependence, et cetera. Other cosmopolitans are skeptical of such a world government because they believe it has great potential for tyranny. They instead advocate for a more robust state-based organization, for example, a United Nations with teeth. What both positions require is locating meaningful political authority at the global level.

On the issue of community, cosmopolitans advocate for the fellowship of all humankind as being the only one with moral intrinsic worth. Such membership is universal – you belong because you are human. Any other membership, from the family you are born into through to religious association and national citizenship, are for the most part an accident of birth. Cosmopolitans argue that if you agree that most of the benefits that define your quality of life are a result of winning the genetic lottery, how can you morally justify the current set of economic and political structures that maintain your privilege? On the issue of justice, advocates of cosmopolitanism argue that individual rights are intrinsic to being human. That the state is often the primary perpetrator of these rights being violated. That some form of a global polity, with defined and enforced rights/responsibilities, is necessary to give substance to questions of justice.

- Watch the Talk to Aljazeera video “The case for cosmopolitanism” by Kwame Anthony Appiah

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal:

- How does Appiah define cosmopolitanism?

- Has the definition changed over time?

- Is cosmopolitanism reconcilable with ethnic differences?

- Can it resist the hierarchies of power?

- Does it threaten the local?

- Why does Appiah argue cosmopolitanism should be a conversation versus a lecture or diplomatic speech?

- Consider the human chain Appiah argues exists in the conversation between the hypothetical ‘neo-Nazi’ and the immigrant.

- How do such human chains empower a cosmopolitan conversation?

- Why Appiah argues we should be highly skeptical when political leaders use the language of ‘us’ versus ‘them’?

- When are people most susceptible to such language?

- In regard to the Middle East, what do you think about Appiah’s argument that ‘pride’ of self may facilitate a cosmopolitan conversation?

- As a cosmopolitanism, how does Appiah try to balance universal human rights and issues of sovereignty and self-determination?

- What about the role of external intervention?

- Contrast his examples of Egypt and China

- What about the role of external intervention?

- What do you see as the strengths and weaknesses of cosmopolitanism?

- How does Appiah define cosmopolitanism?

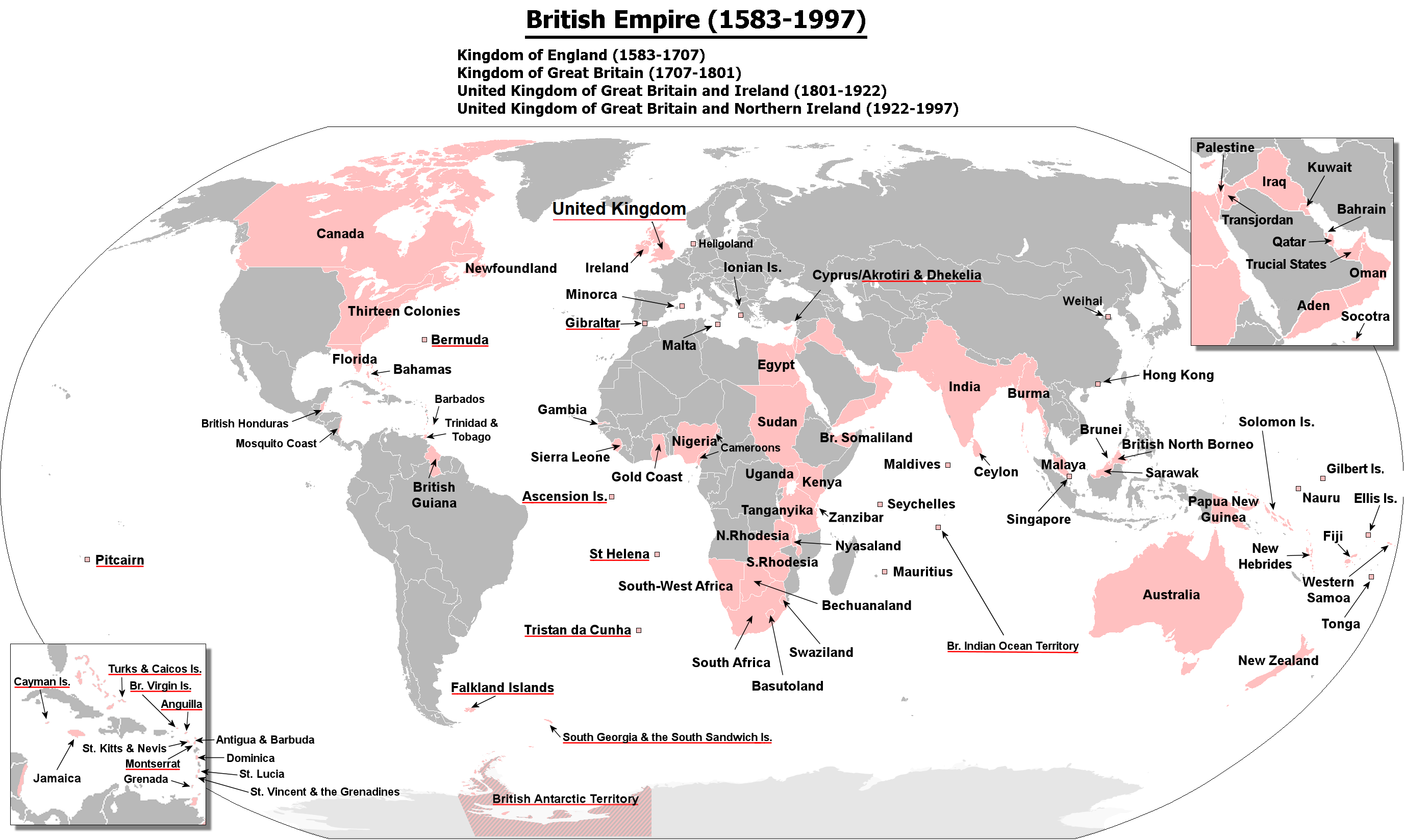

Figure 2-20: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_British_Empire.png#/media/File:The_British_Empire.png) Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of The Red Hat of Pat Ferrick.

As noted in the previous section, varying forms of cosmopolitanism have held the high ground in academia and in the progressive narrative of how we can achieve a more peaceful and equitable world. However, much like the critiques of global citizenship, we saw in module one, many people have been very skeptical of this narrative. The three most robust criticisms of cosmopolitanism center on three broad critiques: equating cosmopolitan ambitions with a world state, questioning the possibility of realizing the cosmopolitan ideal, and questioning whether that ideal is even desirable. The first critique is the least robust and some may even consider it a bit too much of a straw man argument. As we discussed in the previous section, there are some who do believe a world state is necessary to achieve cosmopolitan ideals, but the majority believe that is not only unnecessary but could even be detrimental. A world state is difficult to imagine in practice given the diversity of the world’s population and the seeming ineffectiveness of the global institutions that do exist. However, a world government is a convenient target for anti-cosmopolitan thinkers. It invokes memories of tyranny, imperialism, and of domination; think of British Imperialism or the Nazi’s Third Reich.

Figure 2-21: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WWII,_Europe,_Germany,_%22Nazi_Hierarchy,_Hitler,_Goering,_Goebbels,_Hess%22,_The_Desperate_Years_p143_-_NARA_-_196509.jpg#/media/File:WWII,_Europe,_Germany,_%22Nazi_Hierarchy,_Hitler,_Goering,_Goebbels,_Hess%22,_The_Desperate_Years_p143_-_NARA_-_196509.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Figure 2-22: Source: https://www.pexels.com/photo/white-framed-rectangular-mirror-159935/ Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Abel Tan Jun Yang.

Yet many if not most cosmopolitan thinkers do not advocate for world government. Rather they seek some form of global polity that would likely work through multilateral or multilevel governance. The second critique is more robust: the difficulty in achieving cosmopolitan ideals. This critique comes in two forms. Some argue that we lack the institutional structure necessary for fostering and maintaining identification with community above the state. What institution could reasonably have the legitimate authority to establish and maintain a global polity? The second variation of this critique reasonably points out that in the anarchical world we live in, it is highly unlikely that states will cede the degree of sovereignty necessary to create institutions of global governance with teeth. And without teeth, what is the purpose of such institutions? The third critique focuses on the power inequalities inherent in global politics and argues that even if possible, cosmopolitan ideals would be undesirable. Far from the narrative of progress, of peace, of prosperity, these critics assert that cosmopolitanism would entrench the current inequalities. The western developed world will continue to reap the lopsided benefits of economic globalization. It will use cultural globalization to reinforce the narrative of western exceptionalism. It will use political globalization to provide legitimation for this exercise in coercion. All the while, we will experience increased environmental degradation, increased inequality, and increased push back by those who see the costs outweighing the benefits – including transnational terrorism, global crime syndicates, and an increasing resistance to keep the system going. As should be apparent by now, the criticisms of cosmopolitanism are also heterogeneous. However, most of them can be reconciled within the communitarian rebuttal to cosmopolitanism.

Figure 2-23: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Donald_Trump_and_Prime_Minister_Justin_Trudeau_Joint_Press_Conference,_February_13,_2017.jpg#/media/File:President_Donald_Trump_and_Prime_Minister_Justin_Trudeau_Joint_Press_Conference,_February_13,_2017.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of The White House.

Most communitarianism thought begins from the critique of the universality that defines cosmopolitan ideals. They argue that these universal ideals alienate the deeply human need to belong to a community. Communitarians argue that we cannot know who we are, what we want, nor even how to make such judgments without community. Community is the embodiment of shared history, it is the source of identity, and it deeply informs practices by normatively defining what is right/wrong and good/bad. And again, while there are differences between communitarian thinkers, we can use the four dividing lines introduced in the first section to find some commonalities that hold true for most variants of communitarian thought. On the issue of the permeability of borders, all communitarian thinkers seek to defend or reassert national borders. These sovereign borders not only provide protection for citizens by keeping bad things out, but they also create space for communities to develop and nurture their own values. They create space for the particular nuance of each community.

Figure 2-24: The Korean War – the first UN sanctioned war. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Centurion_tanks_and_infantry_of_the_Gloucestershire_Regiment_advancing_to_attack_Hill_327_in_Korea,_March_1951._BF454.jpg#/media/File:Centurion_tanks_and_infantry_of_the_Gloucestershire_Regiment_advancing_to_attack_Hill_327_in_Korea,_March_1951._BF454.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Think of some of the differences between Canada and the US, health care for instance. In general, Canadians have a deep affinity with their single-payer, universal health care system. Americans on the other hand, have a deep affinity with individual choice absent government influence. Which of these health care systems is right? It is easier to answer questions of efficiency or of cost. But right? What is the metric by which we make such decisions? The same holds true for discussions of gun control or of the relative benefits of a presidential versus a parliamentarian form of government. Communitarians argue such determinations can only be made through the collective lens of community.

On the issue of where political authority should reside, communitarians are deeply suspicious of any attempt to establish a polity above the state. They are deeply skeptical of the idea that enough universal values exist to establish an equitable and just political order, especially anything approximating a world government. Absent such universal values, any global polity would by necessity mean the imposition of one group’s values and norms over another.

On the issue of community, communitarians both assert the primacy of existing national and subnational communities while being deeply suspicious of assertions that a global community exists. In terms of national and subnational communities, communitarians argue that these are not neutral placeholders of atomistic individuals. These are the constitutive communities that both shape us and in turn, are shaped by us. In so doing, communities are placeholders of meaning, values, and identity. They are instrumental to our sense of being. In terms of the purported global community, communitarians argue this is a hollow heuristic. Beyond a philosophical argument of belonging to a common fellowship, what does cosmopolitanism offer in terms of creating a sense of shared belonging? Who is willing to sacrifice in the name of cosmopolitan ideals? Perhaps more importantly, who is being asked to sacrifice in the name of cosmopolitan ideals? Finally, on the issue of justice, advocates of communitarianism argue that it is defined by the freedom of self-determination. Communities require fairly impermeable borders in order to create the space for particular societies to seek their definition of the common good, of the good life. Conversely, any attempt to impose external or supposedly universal values is deeply unjust.

- Read Zakaria, Fareed. 1996. The ABCs of Communitarianism. July 26 . Accessed September 30, 2018. http://www.slate.com/articles/briefing/articles/1996/07/the_abcs_of_communitarianism.html.

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- Why does Aristotle argue that ‘man is by nature a political animal’?

- How does the relate to the concern that humans are increasingly being left feeling ‘hollow at the core’?

- Why does Zakaria seem to argue this is a problematic position for left-wing communitarians?

- Why did Putnam juxtapose the decline in team bowling with the rise of individual bowling?

- How does this support a communitarian argument?

- What role does civil society play in communitarian thought?

- If you compare this article with Appiah’s defence of cosmopolitanism, which argument is more compelling? Why?

- Why does Aristotle argue that ‘man is by nature a political animal’?

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Anarchical: is the idea that we live in a world system in which there is no overarching authority above the state and therefore each state is equally sovereign.

Authority: is the power or right to rule or govern. It is the ability to control, including giving orders, making decisions and can even mean demanding obedience.

Categorical imperative: is the moral obligation that applies unconditionally to all actors and does not depend on any ulterior motive or end. For Kant, there was a categorical imperative to treat all human beings as ends in themselves and not as means to a greater good simply because they are human.

Civil society: are non-state organizations or groups with the power to influence the actions and decisions of elected policy-makers and businesses.

Communitarianism: is the philosophy that the individual is connected to the community, the interest of the community takes precedence over that of the individual and one cannot separate their aims and attachments from their political experience. The good of the community is paramount and justice is what the community defines it as. It privileges collective responsibility which argues people do bear the responsibility and of their family and political community.

Cosmopolitanism: is the idea that individuals have equal moral worth and therefore have reciprocal rights and obligations to each other regardless of citizenship, nationality, religious affiliation, economic class, or place of birth.

Cultural products: are goods and services that are created by a particular culture and reflect the perspectives of that culture. These cultural products can be, and often are, packaged and sold, such as Hollywood/Bollywood movies, Motown, or Anime.

Community: is a social group of people who live in a particular place and share some form of common cultural and/or history. Community can include ethnic, religious, national, geographic, or even digital spaces.

Extreme poverty: is a situation where people experience severe deprivation to the point that they live a day to day existence. Often extreme poverty was traditionally measured by those living on less than a dollar a day. With inflation, that means extreme poverty is measures as 1.90$ per day.

Globalism: is the idea that important economic, political, and cultural processes are operating at the global level and may even be more influential than at the national level. It is a dedication to free trade and free markets based on the belief that people, goods and information should be able to cross national borders without hindrance.

Hard borders: are strongly controlled borders that make the free movement of goods, capital, finance, and labour more difficult.

Inequality: is a disparity in the economic and social status of people. It is the unequal distribution and access to resources and opportunity. It can be measured between people with in the state, between regions or states, and between domestic or international classes.

International organizations: are bodies, most often state based, that aid in organizing the complex international system. They can be political like the UN, economic like the WTO, or work in discrete issue areas such as health (the WHO), transportation (ICAO), or even organizing the internet (ICAAN)

Justice: is fairness in the way people are treated. This includes fairness in the protection of rights and the punishment of wrongdoings.

Moderate cosmopolitanism: is the variant of cosmopolitanism that agrees that we do have a duty to provide aid to those in need regardless of who they are or where they are from but also admits that we have privileged relationships to which we give greater priority.

Non-Governmental Organizations: are non-profit cooperative associations that serve specific political or social purposes and operate independently from governments.

Normative: are the values and ideals that are concerned with what ought to be.

Original position: is the condition in Rawls’ thought experiment where people have no knowledge of themselves nor their circumstances due to the ‘Veil of Ignorance’. This is intended to have people confront their own biases in thinking about the rules that govern society.

Permeability of borders: is the degree of openness of borders that facilitate or hinder movement.

Primordial: means the existence or persistence of something from the beginning. It is the first, initial, or earliest form of something. In reference to nationalism, primordialism means that we are members of particular societies based on our genetic lineage. This has softened over time to mean we are members of a particular society based on our shared histories, culture, and values.

Sovereignty: is the supreme power to impose law in a given polity. In our global system, the state is the highest authority. It is able to rule its territory and people domestically and represent its territory externally.

Straw man argument: is a rhetoric argument whereby the argument of the opponent is distorted in order to make it easier to attack. It involves pretending to refute the argument of the opponent, but in reality, it refutes a different argument that does not represent the opponent’s stance.

Strict cosmopolitanism: is the variant of cosmopolitanism that requires decisions to be made according to need and to strip away any preference or privilege associated with nationality, ethnicity, religious affiliation, or other identity groups.

Supranational: is the status of having power, authority or influence that transcends national boundaries or governments.

The common good: refers to the shared goals of a particular community and is usually linked to id

The good life: is the possession of the things that are good for the human over the course of a lifetime. The good life corresponds to the natural needs of humans, therefore, what is good for one is good for another.

Veil of ignorance: is a thought experiment whereby people are stripped of their history, interests, and identity, and do not know their ethnicity, religion, age, nor what talents they may have when deciding upon the rules of society in the ‘original position’. This allows us to rationally arrive at universal moral principles as the basis of a just society.

World state: is the idea of a global government acting as a common political authority over all states and people.

References

Abate, Mizanie, and Alemayehu Tilahun. 2012. Meaning and scope of international organizations. April 8. Accessed October 1, 2018. http://www.abyssinialaw.com/about-us/item/474-meaning-and-scope-of-international-organizations.

Bell, Daniel. 2016. Communitarianism. March 21. Accessed October 1 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/communitarianism/ .

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopedia. n.d. Categorical imperative. Accessed September 30, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/topic/categorical-imperative.

Business Dictionary. n.d. Justice. Accessed October 1, 2018. Ferguson, Niall. 2010. The Shock of the Global: The 1970s in Perspective. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Carleton University Center for European Studies. n.d. Extension: What are International Organizations? Accessed October 1, 2018. https://carleton.ca/ces/eulearning/introduction/what-is-the-eu/extension-what-are-international-organizations/.

Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition. n.d. Cultural Practices, Products, and Perspectives. Accessed October 1, 2018. http://carla.umn.edu/cobaltt/modules/curriculum/textanalysis/Practices_Products_Perspectives_Examples.pdf.

Effectiviology. 2018. Straw Man Arguments: What They Are and How to Counter Them. https://effectiviology.com/straw-man-arguments-recognize-counter-use/.

Folger, Jean. 2018. What is an NGO (Non-Governmental Organization)? January 8. Accessed October 1, 2018. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/13/what-is-non-government-organization.asp.

Geography.name. n.d. The Permeability of Borders. Accessed October 1, 2018. http://geography.name/the-permeability-of-borders/.

Inman, Phillip. 2016. Study: big corporations dominate list of world's top economic entities. September 12. Accessed October 1, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/sep/12/global-justice-now-study-multinational-businesses-walmart-apple-shell .

Jezard, Adam. 2018. Civil Society. April 23. Accessed October 1, 2018. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/04/what-is-civil-society/.

Keating, Joshua E. 2011. Why Is the IMF Chief Always a European? May 18. Accessed October 1, 2018. https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/05/18/why-is-the-imf-chief-always-a-european/.

Kleingeld, Pauline, and Eric Brown. 2013. Cosmopolitanism. July 1. Accessed October 1, 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cosmopolitanism/.

Messerly, John G. 2013. Aristotle on the good life. 19 December. Accessed September 30, 2018. https://reasonandmeaning.com/2013/12/19/aristotle-on-the-good-and-meaningful- life/#.

Myers, Joe. 2016. How do the world's biggest companies compare to the biggest economies? October 19. Accessed October 1, 2018. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/10/corporations-not-countries-dominate-the-list-of-the-world-s-biggest-economic-entities .

Nuru International. n.d. Extreme Poverty. Accessed October 1, 2018. http://www.nuruinternational.org/why/extreme-poverty/.

Rapkin, David P., and Jonathan R. Strand. 2006. "Reforming the IMF's Weighted Voting System." The World Economy 29 (3): 305-324.

Zakaria, Fareed. 1996. The ABCs of Communitarianism. July 26. Accessed October 1, 2018. http://www.slate.com/articles/briefing/articles/1996/07/the_abcs_of_communitarianism.html.

Supplementary Resources

- Bertrand, Anand. Cosmopolitanism in Modernity: Human Dignity in a Global Age. Logos (Rowman and Littlefield, Inc.). Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2012.

- Brown, Chris. "Cosmopolitan Confusions: A Reply to Hoffman." Paradigms 2, no. 2 (1988): 102-11.

- Etzioni, Amitai. "Communitarianism Revisited." Journal of Political Ideologies 19, no. 3 (2014): 241-60.

- Etzioni, Amitai. The Essential Communitarian Reader. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1998.

- Kleingeld, Pauline. Kant and Cosmopolitanism: The Philosophical Ideal of World Citizenship. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Taraborrelli, Angela, and McGilvray, Ian, Translator. Contemporary Cosmopolitanism. Bloomsbury Political Philosophy. 2015.