Overview

In modules 5 and 6, we looked at institutional responses to the changing context of international politics and the significance of this for global citizenship. More specifically, we looked at institutional innovation globally, including the Concert of Europe, the League of Nations, and the United Nations in module 5. And in module 6, we looked at institutional innovation at the regional level, specifically the European Union and the African Union. These institutional responses are both using a top-down approach. They are crafted by those in positions of power to address issues they perceive as a threat or opportunity for their states and their citizens.

Figure 7-1: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schuman_Washington.jpg#/media/File:Schuman_Washington.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Europeana Collections.

Figure 7-2:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kwame_Nkrumah_(JFKWHP-AR6409-A).jpg#/media/File:Kwame_Nkrumah_(JFKWHP-AR6409-A).jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Abbie Rowe.

To be sure, historical statesmen like Robert Schuman of France or Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana were acting in what they thought to be the best interest of their people. But when you represent the state, your perception of what is best for the country will differ from the individuals and specific groups that constitute the body politic. For example, Prime Minister Trudeau’s perception of Canada's national interest is likely very different from that of someone working the oil patch in Alberta, someone working on an assembly line in an auto factory in Ontario, or someone working in fisheries off the Grand Banks. It is also likely very different from someone dedicated to environmental issues or Indigenous peoples' rights in Canada. The Prime Minister and the government, more generally, have to balance competing interests in the country along with their own political parties and even their own ideological and personal biases. From a grassroots level, individuals and groups try to influence government decision-makers, whether that be Idle No More fighting for Indigenous Rights, the Canadian Labour Congress fighting for workers' rights, or Greenpeace fighting for environmental issues.

Rather than seeking to contend with economic, political, and social issues from the top-down, these groups fight for the people on the ground using a bottom-up approach. In doing so, they are contending with the state and corporate interests that may see things differently. There is a similar dynamic at play at the global level, albeit under far less controlled circumstances given the anarchical nature of international politics. In the literature, three sectors constitute international society. States constitute the ‘first sector’ of international society. As we saw in the last module, the state holds a privileged position in international politics given its monopoly on the use of violence and recognized legal personality. The ‘second sector’ of international society is constituted by economic actors, especially Multi-National Corporations (MNCs). These MNCs have been increasingly dominant in defining economic globalization. The ‘third sector’ of international society is constituted by the global equivalent to domestic civil society. While historically rooted in the role of the free market in opposing authoritarian states, the contemporary concept of civil society is rooted in debates around democracy, citizenship, and human rights. However, within the anarchical environment of international politics, these tensions are less regulated. States are sovereign. Multinational Corporations are extremely powerful and wealthy. The institutions of global governance are relatively weak. In this permissive environment, states and corporations have largely dominated the form and function of international politics. However, much like in domestic politics, global civil society often stands in opposition to state and corporate interests. And much like the role played in domestic politics, global civil society is an important actor in promoting human rights, democracy, and nascent forms of global citizenship. It is to this role that we turn to in this module.

Figure 7-3: Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Idle_No_More_2013_Ottawa_1.jpg#/media/File:Idle_No_More_2013_Ottawa_1.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Moxy.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

1. Define and contextualize the relationship between the civil society, the state, and governance

2. Define the concept of global citizenship

3. Discuss the connection between global civil society and global citizenship

1. Read Michael Muetzelfeldt and Gary Smith. 2002. “Civil Society and Global Governance: The Possibilities for Global Citizenship”.

2. Take the Quiz http://impactjournalismday.com/event/3367/

3. Complete learning activity one.

4. Watch the TEDx Christchurch talk ‘The three essential ingredients for active citizenship’ https://youtu.be/Vr4qtTcU4n8

5. Complete learning activity two.

6. Watch the Tedtalk ‘How to expose the corrupt’ by Peter Eigen

7. Complete learning activity three.

8. Read ‘Global Civil Society in the Global Political Arena’ https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/globalstudies/assets/docs/publications/LisaJordan.pdf

9. Complete learning activity four.

Bottom-up approach

BRICS

Civil society

‘First sector’ of international society

Global civil society

imagined community

International Non-Governmental Organizations

Liberal democratic narrative of global civil society

Neoliberal narrative of global civil society

Second sector’ of international society

Sociological narrative of global civil society

Structural Adjustment Policies

Third sector’ of international society

Top-down approach

‘White saviour’ complex

1. Michael Muetzelfeldt and Gary Smith. 2002. “Civil Society and Global Governance: The Possibilities for Global Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 6 (1), 55-75.

2. Jordan, Lisa. 2006. “Global Civil Society in the Global Political Arena.” University of Victoria. https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/globalstudies/assets/docs/publications/LisaJordan.pdf

Learning Material

Figure 7-4a: Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Msf_logo.svg#/media/File:Msf_logo.svg Permission: Fair Use. b: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hrw_logo.svg#/media/File:Hrw_logo.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Mononomic. c: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Oxfam_logo_vertical.svg#/media/File:Oxfam_logo_vertical.svg Permission: Fair Use.

These are International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs) advocating for solutions to international health crises, human rights abuses, and the rights of at-risk groups. While Doctors Without Borders, Human Rights Watch, and Oxfam Canada are all well known global INGOs, there are thousands of smaller organizations fighting for fair trade, combatting AIDS and the stigmatization that comes with it, promoting democracy and human rights, fighting poverty, disease, and inequality to name just a few issues. More publicly, we can see the face of global civil society in the streets protesting high-level international gatherings like the G7 summits, WTO negotiations, climate change conferences, or the general debate held at the beginning of each UN General Assembly session.

Figure 7-5: G20 Protests in Toronto 2010. Source: https://flic.kr/p/8dEy7J Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Commodore Gandalf Cunningham.

Figure 7-6: Henry Dunant at Solferino. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Battaglia_di_Solferino_(Henry_Dunant).jpg#/media/File:Battaglia_di_Solferino_(Henry_Dunant).jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Both these street protests and the more formal INGOs seek similar goals: to influence, resist, protest, and monitor the implementation of international law and policy. These are the voices of the people seeking to achieve their respective interests in shaping the form and function of our globalized world. This is global civil society, and it is not new. People have organized in reaction to perceived injustice since time immemorial. Early examples of more formalized action can be found in INGOs, like the Anti-Slavery Society, formed in 1839. Or even older, the Sovereign Military Order of Malta which was founded in 1048 and still exists today, carrying out social care and humanitarian aid in 120 states. More well known is the Red Cross, which Henri Dunant founded in the 1860s after witnessing the atrocities of the Battle of Solferino. He saw the way soldiers were treated as cannon fodder and sought to create rules and laws around warfare and, most specifically, the treatment of the wounded.

What is different today compared to the late 19th and early 20th centuries are the number of INGOs and the range of issues they are addressing. There are currently over 20,000 INGOs ranging from smaller niche organizations advocating for narrowly defined issues like net neutrality to large, well-funded organizations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which had an endowment of 43.5 billion US dollars in 2015 and seeks to address issues as broad as global poverty. However, it is important to note that global civil society is by far the least developed of the three sectors of international society, even with exceptions like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Unlike its domestic counterpart, global civil society must contend with states and MNCs in an anarchical environment. There is no overarching authority to ensure everyone is following the rules or even respecting basic rights. INGOs have no authoritative body to seek protection or compensation from when states or corporations act unethically, coercively, or even illegally. Those individuals protesting international summitry are subject to the laws of the state they are in. In politically corrupt or less developed states, such individuals face violent retribution or a lack of protection from official sources. Yet, there is a need for the people’s voices to be heard in our increasingly globalized world. And importantly for our course, global civil society possibly represents a nascent form of global citizenship. This module will first look at the relationship between civil society, the state, and governance. Next, we will turn to an explicit examination of the concept of global civil society. Finally, we will close with an examination of global civil society and global citizenship.

- Before moving on, let us assess your knowledge of the problems global civil society is engaged with.

- Take the Quiz http://impactjournalismday.com/event/3367/

- Share your results in the poll

Figure 7-7: Benito Mussolini (left) beside Adolph Hitler (right). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1969-065-24,_M%C3%BCnchener_Abkommen,_Ankunft_Mussolini.jpg#/media/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1969-065-24,_M%C3%BCnchener_Abkommen,_Ankunft_Mussolini.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Bild.

In our quest to understand or at least meaningfully conceptualize global citizenship, it is useful to consider its domestic counterpart and its relation to the state. As discussed in module one, citizenship both defines formal membership in a political community and the reciprocal rights and obligations that exist within that community. At the core of this relationship between the state and citizens are the concepts of power and authority. Is citizenship defined and implemented in a top-down fashion? Or is citizenship achieved from the bottom-up agitation by civil society against the state? Or is it something between? The result of a mutually constitutive relationship between the state and civil society? The first model that maps the relationship between the state, civil society, and governance suggests that the key variable in understating the form and function of citizenship is state power. A powerful state that is despotic or authoritarian often seeks to limit the emergence of civil society and undermine the rights of citizens. The emergence of the fascist regime in Italy under Mussolini is a good example of this. The goal was to establish a strong state where the individual is subsumed by the state, where human existence only has meaning through the state, and where an individual’s fulfillment is only possible by service to the state.

Figure 7-8: Stephan Harper with Ban Ki Moon at Saving Every Woman Every Child: Within Arm’s Reach Summit. Source: https://flic.kr/p/yinzV6 Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of EasyPoli.

Alternatively, a strong state can also facilitate the conditions under which civil society may flourish. It does so by establishing a social, economic, and legal system that empowers civil society. This is a state that can withstand criticism and may actually even encourage it. This is a state built upon the concept of the rule of law whereby citizens trust the state to fulfill its obligations. At the very least, they believe there is something like an independent judiciary to enforce compliance. Canada is an example of this. Upon achieving independence, the Canadian state has slowly facilitated the emergence of civil society. While the state has certainly not been altruistic, and there are many examples of coercive force being exercised against civil society organizations, Canada, on the whole, has fostered a diverse and, at times, robust civil society. The government provides funding for civil society groups to represent various voices, some of them exercising strong dissent to government policy. For example, the Liberal Government funded the Voluntary Sector Initiative between 2000 and 2005 to build capacity within the voluntary sector and encourage citizens to engage in societal issues. The Conservative government of Stephen Harper, on the other hand, sought to partner with specific civil society groups to pursue government objectives like maternal health or First Nations education, for example.

There are pros and cons to each policy direction, but both recognize the importance of civil society in achieving national goals. Ultimately, whether the state actively impedes the formation of civil society or fosters it, both argue the state is the defining variable in understanding the rights and obligations of citizenship. Alternatively, a second model that maps the relationship between the state, civil society, and governance suggests that civil society defines the form and function of citizenship. From this perspective, it is not the permissiveness of the state that is determinative but rather the social and cultural histories of the people. There are two implications of this. First, as Robert Putnam notes in his exhaustive study of good governance in Italy, if there is a strong cultural predilection towards being civically engaged, there is a strong correlation with governmental success. But perhaps more importantly for our topic of global citizenship, this also raises the question of whether a strong civil society can take root in a state or at the global level if there isn’t a strong cultural/historical tradition of being civically engaged. This has two important implications. First, it suggests that many of the world’s emerging powers may not easily internalize a strong civil society tradition. If we look at the 2016 Gallup poll on Global Civic Engagement, we can see the BRICS, an important emerging bloc of regional powers, have relatively low global civic engagement scores: Brazil (34), Russia (22), India (29), China (11), and South Africa (37). Compare this to the US (61), Australia (60), and Canada (56). That is not to say that western developed states only pursue global civic engagement. For example, developing states with very high scores, such as Myanmar (70) and Sri Lanka (57). But China and India represent roughly 2.7 billion of the 7.7 billion people on the planet. The BRICS taken together represent states that will have a strong formative influence on the character of the international system.

Figure 7-9: BRICS Summit 2016. Source: http://www.wikiwand.com/en/China%E2%80%93India_relations Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0

This leads to the second important implication: it is one thing to have a system of global governance that reflects the values of the dominant liberal democracies in 1945 that do have cultural traditions of civic engagement. It is quite another to have a globalized world where many of the most important states do not have such traditions. Therefore, this second model suggests that achieving a meaningful global civil society and global citizenship may be quite difficult. However, a third model maps the relationship between the state, civil society, and governance that suggests the form and function of citizenship can be mutually emergent between the state and civil society. From this perspective, the state and civil society mutually constitute the shape that citizenship takes and the depth of attachment people have with it. This carves out greater theoretical space for understanding citizenship and effective governance. It allows us to explain the divergent outcomes of the former Soviet States in Eastern Europe in the 1980s and 1990s. Like Poland, some of these states actively facilitated a vigorous civil society, while other states did not. It also allows for Putnam’s thesis on the divergent outcomes in Italy. He noted that despite existing in the same state, a strong concept of citizenship that demanded much of government emerged in the north while it did not happen in the south. And it also allows for the ability to explain change over time as the state and civil society interact. There are important implications of the emergent approach, specifically, the ability to incubate civil society and seek to create virtuous cycles of active citizenship. This opens space for the possibility of an active global civil society where only a weak or disjointed one has existed to date. And this, in turn, allows for the possibility of establishing a meaningful form of global citizenship. We will return to this argument in section three after looking at what contemporary global civil society looks like.

-

- Watch the TEDx Christchurch talk ‘The three essential ingredients for active citizenship’ https://youtu.be/Vr4qtTcU4n8

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- Why does Mr. Liu argue we are currently ‘at the moment of creation’?

- How does he define power?

- Why/how does he argue power is an essential ingredient for active citizenship?

- How can power be claimed?

- How does he define imagination?

- Why/how does he argue imagination is an essential ingredient for active citizenship?

- What are the consequences of a failure of imagination both vis-à-vis global issues and in terms of empathy?

- How does he define civic character?

- Why/how does he argue civic character is an essential ingredient for active citizenship?

- Try to combine the text from section one with Eric Liu’s TEDx talk:

- Is active citizenship a function of state facilitation?

- Is active citizenship a function of a predisposition towards an active civil society?

- Or is active citizenship a mutually emergent function of the state and civil society?

- Using your answers above, consider whether you think it possible to foster active global citizenship?

Figure 7-11: The Fall of the Berlin Wall 1989. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BerlinWall-BrandenburgGate.jpg#/media/File:BerlinWall-BrandenburgGate.jpg Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of Sue Ream.

To understand global civil society, it is useful first to strip the prefix ‘global.’ So what is civil society? We can trace the conceptual roots of the term civil society to the 18th and 19th century Scottish Enlightenment and classic liberalism. This put a strong emphasis on the role of the market in curbing authoritarian impulses and promoting civility in society. However, the contemporary usage of ‘civil society’ refers to the social space outside of the government, the market, and the family. It is in these spaces that individuals and groups recognize and begin to agitate for commonly identified interests. In the post-Cold War world of the 1990s, this literature took on a new significance when theorizing and explaining the trajectory of the democratic transitions happening in the former Soviet States. In seeking to facilitate these transitions, western states sought to enhance civil society in Eastern Europe.

Figure 7-10:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SDG-pyramid.jpg#/media/File:SDG-pyramid.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of United in Diversity.

In contemporary usage, civil society has become equated with any group that is neither state-supported nor profit-motivated. These are groups that operate in the public sphere and putatively in the name of the public good. They seek to raise awareness of issues, advocate for particular solutions, influence decision makers’ choices, monitor policy implementation and represent those adversely affected. They work on global trade issues, international development, extreme poverty, global inequality, democratic governance, human rights, global health, and international peace.

Civil society organizations are largely autonomous actors, constituted by volunteers willing to commit themselves to advance those interests, values, and identities that they believe to be important. As mentioned in the introduction, many argue these groups constitute a necessary third sector of international society that mirrors trends in liberal democratic states. That the interests of states and corporations need to be balanced by advocates acting on the people’s interests. However, there is less agreement on how and why global civil society acts. From the literature, it is possible to identify three broad narratives of global civil society. The first is the liberal democratic narrative of global civil society. Global civil society actors that conform to this narrative seek to defend western liberal democratic norms at home and foster them abroad. These norms include responsible government, the importance of an independent judiciary, institutionalizing human rights, and the advantages of a free and unbiased media. They seek to give meaning to the idea of accountability to both domestic and global citizens. They facilitate those actors seeking to establish good governance to support that accountability. They seek to empower a judiciary that can defend that accountability through the rule of law. From this tradition of liberal democratic theory, global civil society is a potentially powerful means to keep international institutions, coercive states, and covetous corporations in check. It should also be noted that global civil society actors in this tradition are most commonly found in the Global North. A good example of a global civil society actor in this tradition is Transparency International (TI). Transparency International’s core mission is to combat corruption. It was established in 1993 and is headquartered in Berlin. The majority of the work is done through the national chapters located in over 100 countries. TI chapters provide access to information and educational programming to combat corruption and work with organizations and institutions to investigate and expose specific corruption cases. They put a specific emphasis on promoting transparency in elections, government administrations, and government procurement. The national office publishes reports on corruption, with the most well-known being the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). The CPI ranks countries on their perceived levels of corruption and aggregates perception of corruption in international trade. The Canadian Chapter of TI, for example, has recently produced a report on ‘snow washing,’ which demonstrates the ease by which corrupt officials and organized crime can launder dirty international money through Canadian shell companies. TI is an example of a global civil society actor seeking to support liberal democratic norms at home and abroad.

Figure 7-12:

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Transparency_International_Logo.png#/media/File:Transparency_International_Logo.png Permission: Fair Use.

The second approach is the sociological narrative of global civil society. In this tradition, global civil society is posited to be a source of popular resistance to authoritarian states, political/economic elites, and MNCs that they both work with or sometimes work for. There are some similarities between this sociological narrative and the liberal narrative of global civil society. They both perceive global civil society as providing a bulwark against the power of states and companies. For example, the mission of TI would seem to support both the liberal and sociological narratives of global civil society – checking corruption. But there are also significant differences. The liberal narrative acts in support of the status quo in terms of the global international order. The global international order was constructed by the victors of World War Two, primarily the US and UK. In its most benign form, this order seeks to balance the sovereign prerogatives of states and the protection of fundamental individual rights. At its best, this order seeks to use the market economy to increase prosperity and reduce poverty. But the system is also prone to abuse by states and companies who seek to maximize their interests, often at the cost of the most vulnerable communities in the world. For example, the impact of resource exploration on Indigenous communities or the impact of opening economies in the global south to some of the largest MNCs in the world, both leaving local communities insecure and impoverished. On the other hand, the sociological perspective challenges the economic and political structures that reinforce the contemporary international order. These global civil society actors provide a locus of resistance to the status quo, openly challenging institutions and mechanisms that perpetuate poverty and inequality both domestically and internationally. These actors often build on the prescriptions offered by important theoretical schools in the sociological narrative, including Marxist critiques, dependency theorists, and post-colonial analysis. There have been damning critiques of important international institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which privilege the actors, norms, and structures of the Global North. The differences between the World Economic Forum (WEF) and the World Social Forum (WSF) provide a good contrast between global civil society’s liberal and sociological narratives. The WEF, established in 1971, is an annual meeting of about 3,000 of the world’s economic, political, and cultural elite. Think of PM Justin Trudeau hobnobbing with Bono, the Secretary-General of the UN António Guterres, and Joe Kaeser, the German MNC Siemens CEO. They meet to discuss the economic and political threats and opportunities faced by the contemporary institutions of our globalized world. Perhaps more importantly, they meet to try and set the agenda for globalization, especially economic globalization, going forward. But they do not fundamentally nor critically address the norms and key institutional arrangements of the global economic and political order.

Figure 7-13:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_Economic_Forum_logo.svg#/media/File:World_Economic_Forum_logo.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of World Economic Forum.

Figure 7-14:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World-Social-Forum.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of merlin.

Compare the WEF to the WSF. The WSF was established in 2001 with the tagline ‘another world is possible.’ The WSF seeks to provide a space for a wide variety of actors that want to challenge the contemporary form of political and economic globalization. In 2018, over 20,000 delegates from over 700 organizations with several times that number of people in attendance. Many see the WSF as the preeminent manifestation of global civil society. It seeks to foster counter-hegemonic networks and facilitate resistance to structures that reinforce global poverty and inequality. It is by definition a locus of popular resistance. In this comparison, we can see the difference between global civil society’s liberal and sociological narratives.

The third approach is the neoliberal narrative of global civil society. Rather than seeing global civil society as representing a third sector standing in opposition to the interests of states and MNCs, this narrative argues global civil society acts in support of the contemporary neoliberal global order in two important ways. First, it is argued that global civil society actors have filled a void in developing states created by the retreat of social welfare provisions. In the 1970s, many developing economies became highly indebted, leading to the Third World Debt Crisis. Many developing states had few options to overcome these difficulties and had to take loans from the IMF and the World Bank. These loans included Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs), which required borrowers to drastically cut back on expenditures and open their economies to global competition. When the government was subsequently unable to fund healthcare or education, global civil society moved in to be the providers of last resort. This alleviated societal pressure and undermined both revolutionary and reform movements while also legitimating the liberal economic norms of the global north. Second, it is argued that global civil society actors can reinforce the dominant norms of the global north.

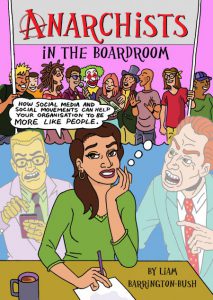

Figure 7-15:

Source: http://jamienotter.com/2013/03/anarchists-in-the-boardroom/ Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

It is argued that many of these actors have a ‘white saviour’ complex, sending secular missionaries to countries in the global south to show the less developed people how to organize their politics, their economies, and even their culture. However, these actors are often funded by the states and MNCs of the global north. While they may provide essential services in developing states or represent marginalized groups, they are often inextricably linked to the interests of the very actors creating the problems they are addressing.

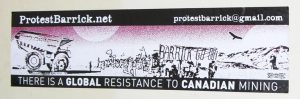

Figure 7-16:

Source: https://flic.kr/p/6M7RqK Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Toban B.

For example, Canadian mining companies have a strong economic interest in Latin America, especially in Mexico, Chile, Peru, Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, and Nicaragua. Both the Canadian government and large mining companies, sometimes acting in concert, have used NGOs in the region to mitigate economic dislocation, build local capacity, and undermine resistance to MNCs. Yet, there is demonstrable evidence of corruption, coercion, and even violence against groups, often indigenous, that oppose these operations. Whether the NGOs’ intentions are honourable or not, they have played a role in maintaining the status quo and legitimating the global economic order. In the next section, we will connect global civil society in its different forms to the idea of global citizenship.

- Watch the Tedtalk ‘How to expose the corrupt’ by Peter Eigen

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal:

- Why does Eigen argue corruption illustrates the failure of governance?

- According to Eigen, why are good projects denied and bad projects approved?

- How are suppliers in the Global North implicated in this corruption?

- How did Transparency International use soft power to try and address grand corruption?

- How can this process be extended to other areas of governance by civil society actors?

- Use the video above and the website https://www.transparency.org/

- Apply the three narratives of global civil society to Transparency International

Figure 7-17:

Source: https://flic.kr/p/cdANYb Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Cambodia4kids.org Beth Kanter.

The last question we need to address in this module is whether global civil society is facilitating, or has the potential to facilitate, the emergence of a more meaningful global citizenship. The first point to consider is the system itself. We have noted in past modules that the world is becoming quantitatively more globalized economically, politically, and culturally. These structures and processes of globalization have quantifiable benefits: access to more goods at a lower price than ever before, reducing global extreme poverty, and rising indicators measuring the quality of life. However, we have also identified some of the quantifiable costs of globalization: environmental degradation, colonial/imperial relationships, sharply increased inequality. In this milieu, it is important to note who is advocating for what and why. The interests of states and the institutions they have created are well represented. The interests of MNCs are also well represented. But what about the people? What about the interests of the individuals and sub-national groups that may or may not favour how our globalized world is unfolding? Global civil society has to a degree, defended these interests but less effectively than states and MNCs have defended theirs. Yes, INGOs have created transnational networks that have sought to address both regional and global problems like corruption, human rights abuses, environmental degradation, nuclear proliferation, global poverty and inequality… the list goes on.

Figure 7-18:

Source: https://www.pexels.com/photo/adult-african-african-american-afro-1559111/Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Pexels.

However, as discussed in the previous section, some of these INGOs advocate for the systemic norms of liberal western democracies in addressing problems. Others are more subversive, questioning the nature of the system itself and in whose interests it operates. Still, others are either knowingly or unwittingly being used by states and MNCs to maintain their privileged position in the system. This highlights an important limitation of global civil society in representing a global polity: its lack of robust legitimacy. INGOs have some democratic legitimacy in that they operate on the capital, both human and financial, of individuals who support their cause – membership and funding represent their public support. But some question this legitimacy in an age where institutions, states, and MNCs provide significant funding to support INGO programming. For global civil society to more fully represent the ‘third sector,’ to be the people’s voice in international society, there is a need to move closer to the concept of global citizenship. But is this possible?

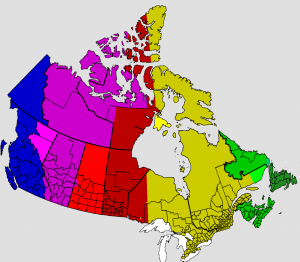

Figure 7-19:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:UTC_hue4map_CAN.png#/media/File:UTC_hue4map_CAN.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Phoenix B 1of3.

If we think back to the first section of this module, we examined three models that map the relationship between the state, civil society, and governance. The third model of mutual emergence may provide a way forward. If citizenship and effective governance are a function of the interplay between the state and civil society, it is possible to see a path towards global citizenship. It would require both states and global civil society, although not all of them, to seek means to reform and strengthen the institutions of global governance. Much as we saw in the regional experiments of governance in the EU and the AU, more powerful and democratically accountable institutions would be able to constrain rogue interests. This would facilitate increased buy-in from the citizens who had or would have suffered without such institutional constraints. This, in turn, would further increase civil society mobilization. And through both increased mobilization and interaction between global civil society actors, it is possible to imagine a nascent identification with global citizenship. While this may seem a difficult and perhaps even doomed enterprise, two arguments are supporting it. First, it is arguably not so different from other forms of group identification. Yes, it may be difficult to imagine that we here in Saskatchewan would feel a kinship with someone living halfway around the world. Yet, someone in Tofino, on the west coast of British Columbia, can feel a national kinship with someone six time zones away in Cape Spear on the east coast of Newfoundland. Moreover, given the multicultural density in Canada, there is no guarantee that these two individuals on the opposite side of the county share any other cultural, political, ethnic, or religious markers. Yet, they both identify as Canadian. And this means they have, to some degree, mutual rights and responsibilities to each other as citizens. Even if they have never met, they are both part of what Benedict Anderson calls an imagined community. Is it so different to imagine we are part of a global community with some degree of reciprocal rights and obligations to one another? Perhaps a better question is: what will our globalized world look like in the future without some form of global citizenship? This brings us to the second argument supporting the conscious facilitation of global citizenship – it is arguably necessary. As the world becomes more globalized, it is becoming increasingly important for the third sector to represent the voices of the people. Without such representation, the system will continue to reflect the interests of states and MNCs. This may lead to a perception that the international system lacks legitimacy, which may increase discontent, calls for reform, and ultimately lead to systemic protest and violence both within and between states. However, if history is any judge, it may just take such a tragic event to push humanity towards a more democratic and representative form of global governance that consciously seeks to foster meaningful global governance.

- Read ‘Global Civil Society in the Global Political Arena’ https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/globalstudies/assets/docs/publications/LisaJordan.pdf

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- How can global civil society enhance the effectiveness of global governance?

- What areas have global civil society actors neglected, and why is this a problem?

- Why and how should global civil society address problems that states and markets often ignore?

- How can global civil society contribute to global norm creation? Why is this significant?

- What problems are global civil society facing, and how might an emphasis on global citizenship be helpful?

- Why are elitism and democratic accountability within civil society organizations a problem?

- Do you think that global civil society is a means to achieve global citizenship?

- If yes, how?

- If no, why not?

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Bottom-up approach: is a grassroots method of local organization and mobilization in the interest of ordinary citizens, individuals, or stakeholders which experience an issue firsthand

BRICS: is an abbreviation for Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. They are large emerging economies in similar stages of newly advanced economic development and are regionally dominant.

Civil society: are non-state organizations or groups with the power to influence the actions and decisions of elected policy-makers and businesses.

‘First sector’ of international society: consists of states in a privileged position in international politics through their monopoly on the use of violence and recognized legal personality.

Global civil society: are groups that operate across borders and nominally independent from both the government and corporate entities.

imagined community: is a socially constructed polity by those who imagine themselves to be members of that group. Those who identify as members of an imagined community feel a connection or kinship with others of that community.

International Non-Governmental Organizations: are non-profit cooperative associations that serve specific political or social purposes and operate independently from governments. They are not established by international treaties or inter-state agreements.

Liberal democratic narrative of global civil society: views global civil society as a means to defend western liberal democratic norms at home and foster them abroad.

Neoliberal narrative of global civil society: argues that global civil society acts in support of the contemporary neoliberal global order by filling the void in developing states created by the retreat of social welfare provisions and by reinforcing the dominant norms of the global north

‘Second sector’ of international society: consists of economic actors, particularly Multinational Corporations, who have been increasingly dominant in defining economic globalization.

Sociological narrative of global civil society: posits global civil society as a source of popular resistance to authoritarian states, political/economic elites, and to the MNCs that they both work with or sometimes work for.

Structural Adjustment Policies: were conditions put on loans given by the IMF and World Bank to highly indebted developing economies which required borrowers to drastically cut back on expenditures and to open their economies to global competition.

‘Third sector’ of international society: consists of the global equivalent of civil society who play an important role in promoting human rights, democracy, and burgeoning global citizenship. They are often in opposition to state and corporate interests.

Top-down approach: are crafted by those in positions of power to address issues that they perceive to be a threat or opportunity for their states and their citizens.

‘White saviour’ complex: is the idea that the white person is the hero that can help non-white people and solve their problems.

References

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London. New York: Verso

Alemanno, Alberto. 2018. What does Davos do to improve the state of the world? January 29. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/01/what-does-davos-do-to-improve-the-state-of-the-world.

Anti-Slavery International. n.d. Our history. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.antislavery.org/about-us/history/.

Augustine, Jean. 2002. Parliament and Civil Society. Accessed December 11, 2018. http://revparl.ca/english/issue.asp?param=82&art=242.

Barry-Shaw, Nikolas, Yves Engler, and Dru Oja Jay. 2012. Paved with good intentions: Canada's development NGOs from idealism to imperialism. Black Point, Nova Scotia: Fernwood.

Berlinger, Joshua, and Rebecca Wright. 2016. Myanmar military burned Rohingya villages, Human Rights Watch says. December 13. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2016/12/13/asia/myanmar-rakhine-state-villages/index.html.

Blanc, Paul Le, and Stephanie Luce. 2003. The World Social Forum and Global Justice. March-April. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://solidarity-us.org/atc/103/p1070/.

Canadian International Development Platform . n.d. Canadian Mining in Latin America. Accessed December 11, 2018. http://cidpnsi.ca/canadian-mining-investments-in-latin-america/.

Cane, Peter, and Joanne Conaghan. 2009. The New Oxford Companion to Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carothers, Thomas. 1999. Western Civil-Society Aid to Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. September 1. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://carnegieendowment.org/1999/09/01/western-civil-society-aid-to-eastern-europe-and-former-soviet-union-pub-145.

Fink, Sheri, Adam Nossiter, and James Kanter. 2014. Doctors Without Borders Evolves as It Forms the Vanguard in Ebola Fight. October 10. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/11/world/africa/doctors-without-borders-evolves-as-it-forms-the-vanguard-in-ebola-fight-.html.

Gallup. 2016. 2016 Global Civic Engagement. Report, Washington DC: Gallup Inc. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.shqiperiajone.org/sites/default/files/pdf/2016%20Global%20Civic%20Engagement%20Report.pdf.

Gordon, Todd, and Jeffery R Webber. 2008. "Imperialism and Resistance: Canadian mining companies in Latin America." Third World Quarterly 29 (1): 63-87. http://blogs.ubc.ca/geog328/files/2015/09/gordon-webber-imperialism-and-resistance.pdf.

n.d. Is Transparency International's measure of corruption still valid? Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2013/dec/03/transparency-international-measure-corruption-valid.

Jordan, Lisa. 2006. "Global Civil Society in the Global Political Arena." University of Victoria. July. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/globalstudies/assets/docs/publications/LisaJordan.pdf.

Keane, John. 2003. Global Civil Society? November/December. Accessed December 12, 2018. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/2003-11-01/global-civil-society.

Marchetti, Raffaele. 2016. Global Civil Society. December 28. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.e-ir.info/2016/12/28/global-civil-society/.

Mathiesen, Karl. 2015. What is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation? March 16. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/mar/16/what-is-the-bill-and-melinda-gates-foundation.

Muetzelfeldt, Michael, and Gary Smith. 2002. "Civil Society and Global Governance: The Possibilities for Global Citizenship." Citizenship Studies 6 (1): 55-75.

n.d. Order of Malta. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.orderofmalta.int/ .

Speer, Sean. 2016. A Conservative Plan To Revive Canadian Civil Society. January 11. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/sean-speer/revive-canadian-civil-society_b_8956944.html.

Transparency International Canada. 2018. Media Release: Budget 2018 – Canada Needs to be More Courageous in Fighting Snow Washing. February 28. Accessed December 11, 2018. http://www.transparencycanada.ca/news/media-release-budget-2018-canada-needs-courageous-fighting-snow-washing/.

n.d. Transparency International Canada Home. Accessed December 11, 2018. http://www.transparencycanada.ca/?

UNDP. n.d. "NGOs and CSOs: A Note on Terminology." United Nations Development Programme. Accessed December 11, 2018. http://www.cn.undp.org/content/dam/china/docs/Publications/UNDP-CH03%20Annexes.pdf.

Walker, James W. St.G., and Andrew S.Thompson. 2008. Critical Mass: The Emergence of Global Civil Society. Centre for International Governance Innovation; Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/walker_thompson.pdf.

Welch, Michael. 2016. "“The Non-Profit Industrial Complex”, and the Co-opting of the NGO Environmental Movement." Global Research: The Centre for Research on Globalization. April 4. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.globalresearch.ca/the-non-profit-industrial-complex-and-the-co-opting-of-the-ngo-environmental-movement/5521526.

Wright, Teresa. 2018. Canada should do more to help women refugees worldwide: Oxfam Canada. October 16. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/canada-should-do-more-to-help-women-refugees-worldwide-oxfam-canada-1.4135725

Supplementary Resources

- Anderson, Benedict R. Imagined Communities Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev. ed. London; New York: Verso, 2006.

- Chandler, David., Baker, Gideon. Global Civil Society: Contested Futures. London; New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Munck, Ronaldo, and Rupert Taylor. "Global Civil Society." In Third Sector Research, 317-26. New York, NY: Springer New York, 2010.

- Walker, James W. St. G., Thompson, Andrew S., and Global Civil Society Conference. Critical Mass : The Emergence of Global Civil Society. Studies in International Governance. Waterloo, Ont.]: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2008.