Overview

Figure 9-1:

Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/RUqoVelx59I Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Dustan Woodhouse on Unsplash (https://unsplash.com/license).

In this module, we move away from both the conceptual definitions of global citizenship and the broader conceptual structures they are embedded within. Instead, we are going to apply these concepts and structural propositions with concrete global issues. In module 10, we will examine the issue of human rights. In particular, we will look at the schism between the universal conception of human rights and the much less than universal application of such rights. In module 11, we will examine migration, which is, and will likely continue to be, the most contentious test of global citizenship. It is one thing to talk about global rights and obligations in the abstract but quite another to create and implement a real-world migration policy that accounts for such rights. However, in this module, we will begin with environmentalism, both one of the earliest recognized ‘global issues’ and one which has served as one of the most effective rallying cries for global citizenship.

Figure 9-2:

Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/ny1lrQy5C-0 Permission; Public Domain. Photo by Stephan Valentin on Unsplash (https://unsplash.com/license).

Environmental concerns are very often global in nature. The atmosphere, the oceans, and the demand for natural resources do not stop at human-created political borders. Similarly, the pollutants generated by human activity do not restrict their impact on the communities from which they originated. The earth is under siege, from nuclear powerplant meltdowns to garbage produced by pre-peeled oranges wrapped in plastic. The processes of globalization have played a large part in magnifying global environmental threats. Many argue we have internalized and glorified an unsustainable lifestyle from the industrial revolution to a global mass consumer culture. They argue that we have far surpassed the planet’s carrying capacity… and we are not slowing down. The planet can sustain 1.5 billion people if we use the American standard of living as a baseline – something advertised on every TV and computer screen in the world. To sustain all 7 billion-plus people on the planet living the American dream would require more than 4 planets.

The stress being placed on the global environment has led to climate change, deforestation, mass species extinction, air pollution, and a worrying decline in access to clean drinking water. It has been widely accepted that these problems are not localized. They are rooted in or have at least been greatly exacerbated by globalization's form and processes. It is also widely accepted that any meaningful response to environmental issues will, by necessity, be global. As such, debates on global environmentalism are often couched in the language of global citizenship. They speak of the global commons. They speak of preserving the environment for future generations. They speak of environmental rights and obligations – in other words, debates on global environmentalism are intricately tied up with debates of global citizenship. That is not to say such positions are uncontested as we will see. It is one thing to recognize the global scope of a problem and quite another to agree upon global solutions. Therefore, in this module, we will first introduce the rise of the global environmental movement. We will then look at the connection to ethics and human rights in environmental issues. Finally, we will assess the nexus between global environmentalism and global citizenship.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define and contextualize the concept of global environmentalism

- Debate the ethics of global environmentalism

- Debate the nexus between global environmentalism and global citizenship

- Take the Quiz https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/global-warming/global-warming-quiz/

- Complete Learning Activity #1

- Watch the BBC video ‘Why we’re heading for a climate catastrophe’ https://youtu.be/pJ1HRGA8g10

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Watch the Ted Talk ‘Why Climate Change is a Threat to Human Rights’ by Mary Robinson https://youtu.be/7JVTirBEfho

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Read The Conversation Article “Caring about Climate Change: Global Citizens and Moral Decision Making” https://theconversation.com/caring-about-climate-change-global-citizens-and-moral-decision-making-44771

- Complete Learning Activity #4

Air pollution

Brundtland Report

Chernobyl nuclear reactor meltdown

Climate change

Cuyahoga river fire

Deforestation

Developed economies

Developing economies

Environmental externalities.

Environmentalism

Free riders

Friends of the earth

Global commons

Greenpeace

Hole in the ozone layer

Industrial revolution

Intergenerational responsibility

Kyoto protocol

Mass consumer culture

Mass species extinction

Multilateral environmental agreements

Rawlsian approach

Silent spring

Sustainable development

The Montreal Protocol

The Paris Agreement

Tragedy of the commons

UN Environment Programme

UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Stephen M. Gardiner. 2004. “Ethics and Global Climate Change.” Ethics 114, 555-600. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/382247

The Conversation. 2015. “Caring about Climate Change: Global Citizens and Moral Decision Making.” The Conversation Canada. https://theconversation.com/caring-about-climate-change-global-citizens-and-moral-decision-making-44771.

Learning Material

Figure 9-3:

Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/pF_2lrjWiJE Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Gustavo Quepon on Unsplash (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 9-4:

Source: https://flic.kr/p/RndWL5 Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of ibmphoto24.

As we have discussed several times in this class, debates on global citizenship are deeply embedded in questions around the rights and obligations that transcend national borders. What duties do I as an individual and we as a collective owe those who live outside our sovereign borders? What rights do we have? How can such rights and obligations be enacted and enforced? And vice versa: what can we expect of others? These questions are closely mirrored in the debates on environmentalism. Do we have a right to clean air? Clean water? A global economy that sustains our needs but also our environment? Do we have an obligation to ensure our activities are not causing environmental harm to others both now and in the future? And if we do have environmental rights and obligations that transcend national boundaries, how are they defined? Who are they to be defined by, and with what authority? If such rights can be legitimately defined, how are they to be enacted and enforced? On the one side, global environmentalism would seem to be a natural starting point for discussions of global citizenship. Environmental issues tend to be regional or even global in nature. Air pollution in one state will often be an issue for neighbouring states, requiring at minimum bilateral cooperation to address. On the other hand, climate change will require a critical mass of the biggest states, in terms of both population and intensity of resource use, to address. Moreover, many contemporary environmental issues are a result of or are deeply compounded by globalization processes. Our globalized economy is resource-intensive. Everything from our smartphones to the food in our grocery stores is constituted by supply chains that reach worldwide: rare earth minerals from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to quinoa from Peru.

Figure 9-5:

Source: https://flic.kr/p/bn7JvF Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Hani Amir.

This has been facilitated by globalized transportation and communication technology that rarely includes the cost of environmental externalities. Cultural globalization has served to market a Western consumer lifestyle that is unsustainable, as we noted earlier. Think of your family’s lifestyle: the food you consume, the clothes you wear, the devices you use, the number of cars your family drives… Now imagine that was the norm for the 7 billion-plus people on the planet. How could this conceivably be sustainable? These are questions and issues that need to be addressed at a global level. The right to clean air, water, and land should be unquestionable. It should not be contentious that we have an obligation to ensure our activities individually and collectively are not depriving others of these rights. However, it is not hard to find examples of how Canadians and the Canadian government are deeply infringing on people’s environmental rights outside of Canada. According to a Greenpeace article, Canada exported 100,618 tonnes of plastic a year to China for recycling before China banned the practice in 2015 due to environmental concerns. Since 2015, Canada has exported its plastic garbage to other countries like Taiwan, South Korea, Turkey, Pakistan, and Indonesia. However, most problematically, are Canadian exports of plastic to Malaysia, resulting in the rise of illegal, unregulated, and harmful practices like the open burning of plastics in or near residential areas. This is just one example of how Canada, like other developed economies, has maintained a high consumption lifestyle while exporting the harmful effects to other poorer parts of the world. At the same time, many governments are mandating restrictions on how much waste can be sent to their own landfills. As Malaysia’s Environment Minister Yeo Bee Yin argues, “no developing nation should be the dumping site for the developed world.” Such practices are deceptive and unsustainable. It is argued that by 2030, such pollution exports will have nowhere to go.

This suggests that there are two points of significance for our discussion of global citizenship. First, recognizing that everyone has rights and obligations, at least theoretically, pertains to the environment: clean air, water, and land. Second, that in practice, there are serious obstacles to defining, implementing, and defending such rights and obligations. This gap between global environmental theory and practice is meaningful to the concept of global citizenship. To this end, this module will first introduce the global environmental movement. We will then look at debates on the ethics and human rights of global environmental issues. Finally, we will look at the connection between the environmental movement and global citizenship.

- Before moving on, let us assess how much you know about global warming

- Take the Quiz https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/global-warming/global-warming-quiz/

- On the live poll app, record your score

Figure 9-6:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diane_aupr%C3%A8s_du_cadavre_d%27Orion.jpg#/media/File:Diane_aupr%C3%A8s_du_cadavre_d%27Orion.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Daniel Seiter – Louvre.

Figure 9-7:

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7e/Pieter_Brueghel_the_Elder_-_The_Dutch_Proverbs_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Environmentalism is not a new concern. Our earliest ancestors likely recognized the impact of environmental change as they had to adjust to the new migration patterns of the animals they hunted and the long-term shifts in the plants they gathered. Most traditional and ancient cultures have referred to the need for balance between humans and nature. In Mesopotamia, the Epic of Gilgamesh (2150-1400 BCE) refers to the anger and retribution of the gods for cutting down sacred trees. In Ancient Greek mythology, the hunter Orion was first attacked by Gaia and then slain by Artemis for threatening to kill all the animals as a demonstration of his hunting prowess.

The Greek philosopher Plato recognized the existence and impact of deforestation and soil erosion, as have ancient writings in China, India, and Peru. Hippocrates, of the Hippocratic oath, wrote the earliest European text on ecology around 400 BC. Many Indigenous peoples view the natural world as sacred and seek a balance between all living things. Some of the environmental problems we struggle with today, like air pollution, have been recognized as issues for hundreds of years – English King Edward I tried to limit coal burning to fight smog in 1306. In the 16th century, Dutch Artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder drew attention to raw sewage polluting the rivers by painting portraits of the desecration.

Figure 9-8:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caspar_David_Friedrich_-_Wanderer_above_the_sea_of_fog.jpg#/media/File:Caspar_David_Friedrich_-_Wanderer_above_the_sea_of_fog.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Caspar David Friedrich.

In the 18th century, the foundation of the modern environmental movement started to take shape in response to industrialization and urbanization. Benjamin Franklin fought for better waste management in Philadelphia to avoid disease outbreaks like yellow fever. At the same time, Thomas Malthus was writing on the dangers of overpopulation. Even the mechanics of global warming was recognized as far back as 1822 when Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier wrote how heat could be trapped in the atmosphere like a greenhouse. The early language of the environmental movement can be traced to the Romanticism movement of the 1800s, which challenged the obsession of viewing everything through an industrial and scientific lens. Instead, they highlighted the intrinsic role that nature played in human emotion and human spiritual wellness.

Much of this early activism arose in response to the unchecked pollution being generated by the industrial revolution, especially as it began to encroach on farmland, forests, and other natural settings. Like the Sierra Club, groups began to form to advocate for government-protected nature preserves and national parks – like Yellowstone National Park (1872) and Yosemite National Park (1890). In the early 20th century, environmental groups continued to grow, like the National Audubon Society in 1905. In the same year, the term ‘smog’ was coined by Henry Antoine Des Voeux. In the 1930s, the ‘dust bowl’ of the prairies was created by poor land management, deforestation, and soil erosion, exacerbated by drought. Many countries begin to legislate preservation acts. In 1948, the World Conservation Union was established in Switzerland. In 1949, Aldo Leopold published a popular book in the environmental community, A Sand Country Almanac, where he argues for a ‘land ethic’ – establishing a balanced relationship between the people and the land. In the 1950s, the UN created the World Meteorological Organization. The Soviets opened the first nuclear power plant, followed by others in the US and Europe, leading to more governmental regulatory bodies being created.

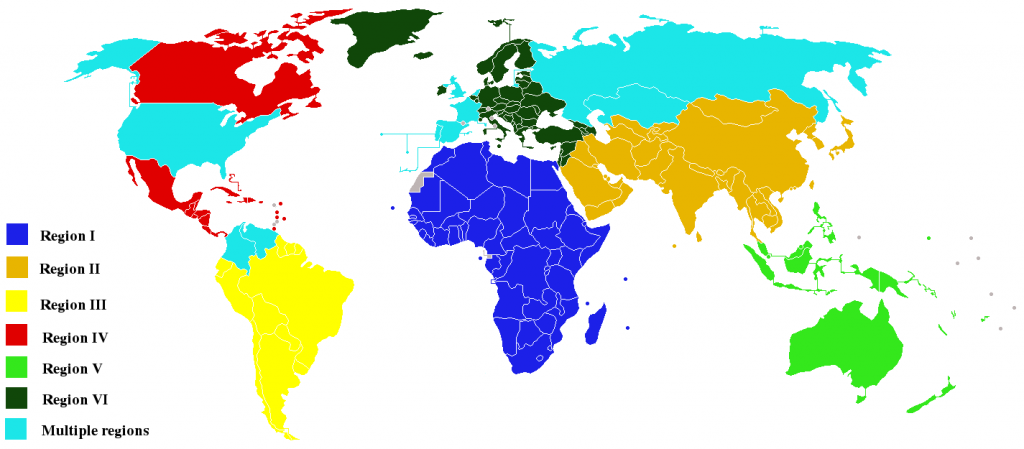

Figure 9-9:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WMO_Regions.PNG#/media/File:WMO_Regions.PNG Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Mátyás.

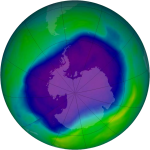

Figure 9-11:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NASA_and_NOAA_Announce_Ozone_Hole_is_a_Double_Record_Breaker.png#/media/File:NASA_and_NOAA_Announce_Ozone_Hole_is_a_Double_Record_Breaker.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of NASA.

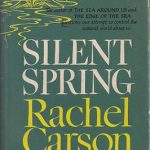

Figure 9-10:

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SilentSpring.jpg#/media/File:SilentSpring.jpg Permission: Fair Use.

However, it is the 1960s where the contemporary environmental movement is considered to have gone mainstream. In 1962, Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring – a damning critique of the pesticides poisoning the environment, our food supply, and, by extension, us. She details how human activity was, and still is, poisoning our food chain – essentially, she is arguing we are killing ourselves. Unlike earlier books that circulated primarily within the environmentalist clique, like A Sand Country Almanac, Carson’s book went mainstream. A debate began in the general public on regulating our interaction with the environment to protect the general welfare.

This spark in the mainstream imagination was further flamed by spectacles like the Cuyahoga River fire in 1969, where a river literally caught fire due to pollution. In response to the Cuyahoga River Fire and other environmental disasters, the Federal Environmental Protection Agency was created in 1970, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency in 1972, and the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972. The 1970s also saw increased international environmental organization. On the civil society front, Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace were founded. Friends of the Earth was established as an international anti-nuclear movement but quickly evolved to cover global issues from desertification and the melting of the polar ice caps to economic justice issues and critiquing neoliberal economics. Greenpeace started in Canada as an anti-nuclear group, specifically against testing nuclear weapons on the Alaskan island of Amchitka. It has evolved into one of the most preeminent international environmental groups, now based in the Netherlands with offices in 40 countries and almost three million members.

Institutionally, the first UN Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm in 1972, led by Canadian under-secretary Maurice Strong. This would be the first of what would later be called ‘Earth Summits’ – conferences held every 10 years to discuss and seek the means to further the idea of sustainable development. The inaugural Earth Summit in 1972 produced the first ‘state of the environment’ report and led to the establishment of the UN Environment Programme. In the 1980s, domestic and international environmental organizations became more institutionalized, researching light pollution, water pollution, ocean pollution, air pollution, and even noise pollution. Within these areas, global epistemic communities began to become more formalized, sharing research and insight. In the 1980s, two important events pushed the environmental movement into the mainstream consciousness. The first was the widespread recognition of the hole in the ozone layer and its connection to skin cancer. The damage to the ozone layer was caused by Chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, and was strongly linked to the increase of UV-B radiation. Much like Carson’s argument in Silent Spring, the hole in the ozone layer and the spread of skin cancer was argued to be self-inflicted – through our use of CFCs in air conditioners and in aerosols, we were once again pursuing self-harming behaviour, and we required regulation but at the global level. The result was the total ban on CFCs via the Montreal Protocol in 1987 and the subsequent healing of the ozone layer. The second important event in the 1980s that stimulated a strong global environmental reaction was the Chernobyl nuclear reactor meltdown in 1986. This led to a large release of radioactive material into the atmosphere, which could be detected from Finland and Iceland to Portugal, Greece, and Turkey. This stimulated domestic opposition to nuclear energy programs at home and international activism against nuclear power around the globe.

Figure 9-13:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chernobyl_radiation_map_1996.svg#/media/File:Chernobyl_radiation_map_1996.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.5

Figure 9-12: Angra dos Reis, Rio de Janeiro. 07/04/2009. Ativistas do Greenpeace instalam balsa flutuante com quatro turbinas eólicas simbólicas em frente às usinas nucleares de Angra dos Reis (RJ) para protestar contra os investimentos do governo brasileiro na construção de Angra 3 enquanto o potencial eólico do país é desprezado. Esta foi a última atividade da expedição “Salvar o Planeta. É Agora ou Agora” que, desde janeiro, percorreu sete cidades brasileiras para debater com a sociedade, indústria e governo soluções reais para combater o aquecimento global.

Source: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Angra_3-Greenpeace_(7345547512).jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Alex Carvalho.

In 1983, the World Commission on Environment and Development was held as a 10-year follow-up to the 1972 Earth Summit. Former Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Brundtland chaired it. It produced the Brundtland Report, which established the idea of sustainable development – an idea at the heart of the current UN development project, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainable development seeks to reconcile the environmental and economic aspects of development. In the 1990s, two important themes emerged in the global environmental discourse: global warming and the north/south divide. Both themes were identified at the third Earth Summit held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. In terms of global warming, the summit led to the Kyoto Protocol: an ultimately failed attempt to cut CO2 emissions to curb global warming. The second theme, the north/south divide, emerged as an important obstacle to the Kyoto Protocol and other substantive measures to address comprehensive environmental issues. The more developed economies of the global north have been highly resistant to binding targets on reductions to CO2 emissions, even if that might not be evident in their rhetoric. They are especially resistant when developing economies are given exemptions to binding targets. On the other hand, the countries of the global south face challenging developmental obstacles and point to the hypocrisy of the global north asking them to put environmental concerns over fighting poverty. They claim environmental regulations did not constrain the countries of the global north as they matured their economies and that many of the environmental problems being faced today are of their making. This fissure between the developed and developing economies remains an issue today. In the 2000s, environmental issues have become fully integrated into the mainstream political narrative. Around the world, environmental issues have been identified, environmental groups have been formed, environmental political parties have fought elections, and environmental policies have been debated, passed, and enacted. Environmental issues are widely recognized, from species protection and combatting pollution to sustainability and climate change. Important victories have been achieved, like healing the ozone layer, but many issues seem intractable. Clean drinking water is increasingly scarce. The global commons is increasingly polluted. The climate is changing.

Figure 9-14:

Source: https://flic.kr/p/4Kf1c3 Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Chuck Taylor.

And since the financial crisis of 2008, economic decision-making has again often trumped environmental protection. The successes are usually localized to specific actors who have a stake in dealing with it or have identifiable solutions that are not overly cost-prohibitive. The failures are often global and comprehensive, requiring a broad commitment from a large number of actors to solutions that are less concrete and entail high economic costs. The biggest risk in global and comprehensive solutions to environmental issues are free riders – actors who benefit from a collective agreement while contributing little to no resources towards its goals. This brings us to the Paris Agreement, the most current global environmental action plan. It was reached in 2015 and was intended to be a significant contribution to mitigating climate change. Climate change has been identified by many as perhaps the most significant environmental threat we face today. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that current trends in CO2 emissions will result in a global temperature increase ranging between 1.6 and 5.8 degrees Celsius by the year 2100. The consequences of this temperature increase are debated but are potentially devastating, including rising sea levels, more extreme weather patterns, and a flood of environmental refugees. For example, the UN predicts the Maldives will be entirely submerged if current trends of CO2 emissions do not change. While the success of the Montreal Protocol had suggested it is possible to negotiate and achieve significant gains in global environmental governance, global warming and climate change have proven more vexing.

Figure 9-15:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Intergovernmental_Panel_on_Climate_Change_Logo.svg#/media/File:Intergovernmental_Panel_on_Climate_Change_Logo.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change.

The Kyoto Protocol attempted to address global warming through the implementation of a global carbon trading system. However, disagreements over things like exemptions granted to developing economies and the associated implementation costs led to defections, most notably the US in 2001. Canada also abandoned its commitment in 2011. In 2015, the Paris Agreement represented a renewed effort in addressing climate change. It included both developing and developed economies and has been signed by 195 states. It takes effect in 2020 and requires various measures to keep the total global temperature increase below 2 degrees pre-industrial levels by the year 2100. The agreement was well received and represents a significant improvement over the Kyoto Protocol in terms of the diversity of tools available to states, recognizing the need for adaptation provisions, and agreeing to mechanisms for monitoring the agreement’s implementation. However, there are also significant criticisms of the Paris Agreement. It is argued that the targets agreed to do will not be enough to avoid the consequences of climate change. Further, it is argued that the reason the agreement was not ambitious enough is rooted in politics and economics, trumping science and environmental realities. The agreement is also criticized for its lack of specificity on how each state will achieve their commitments and the consequences of not achieving them. But the greatest threat to the Paris Agreement comes from the receding will for global action. Many countries are becoming more inward-focused and fighting for their own more narrowly defined national interest. They are less concerned with absolute threats in the long term than they are with relative threats in the short term. In other words, when President Trump signalled his intention to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement at the first opportunity, which is 2020, he is saying that the US is more concerned with the rising economic challenge of China and India than he is with the potentially catastrophic consequences of unchecked global warming and climate change.

Signatories to the Paris Agreement Parties Signatories Parties covered by the EU) So where are we now? Well, the 2018 special report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is not optimistic. They argue that we are nearing a tipping point, where it is no longer a case of mitigating climate change and more a case of adapting to the potentially catastrophic consequences.

Figure 9-16:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ParisAgreement.svg#/media/File:ParisAgreement.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of L.tak.

- Watch the BBC video ‘Why we’re heading for a climate catastrophe’

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What are the potential consequences of not mitigating climate change?

- What is required to achieve a net carbon emission of zero by 2050?

- Why is this a political question/problem?

- How does the current debate on climate change in the US represent both the political nature of climate change policy and the problem of achieving meaningful policy to address it?

- Why is it significant that climate change is anthropogenic?

- What would you like the Canadian government to do vis-à-vis climate change?

- What do you think the future of climate change will look like?

Figure 9-17:

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b5/Countries_by_carbon_dioxide_emissions_world_map.PNG Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0

So far, we have introduced the development of environmentalism and, in particular global environmentalism. We noted the move from local environmental problems, like the smog of London, to bilateral or regional problems like cross-border waterways and international environmental problems like global warming and climate change. We have seen that addressing contemporary environmental threats like climate change will require a robust global response. We have also noted the difficulty entailed in agreeing to an effective global response due to the complexity of the required solutions, the cost involved in implementing complex solutions, and the incentives to defect from agreements or become free riders. On the other side of the argument, we have also stated that it is not contentious, at least in theory, to say people should have a right to clean air, clean water, and habitable land. If we combine this statement with the fact that political borders do not contain environmental problems, we can argue that we individually and collectively have environmental rights and obligations that extend beyond our national borders. This suggests that environmental issues contain questions of ethics and human rights. This section will touch on three ethics/human rights issues associated with global environmentalism: deciding on the responsibility for the past, the problematic nature of a global commons, and intergenerational responsibility.

Figure 9-18:

Source: https://flic.kr/p/jW5vry Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

The first issue we will look at is the ‘responsibility for the past.’ This is perhaps the issue at the crux of the schism between the developed and developing economies when dealing with issues like climate change. Climate change did not randomly appear. Rather, it is a result of the historical processes of economic, political, and cultural globalization. The world’s developed economies have spent 200+ years industrializing, urbanizing, and spreading their economic, political, and cultural norms. They have been able to mature their economies without serious regard for global environmental policy. They may have adjusted policy to mitigate economic externalities being felt by domestic constituents: air and water pollution, for example. But they were not asked to agree to multilateral environmental agreements that would have limited their economic development. Now, these states are transitioning into less environmentally damaging economic activity and are now asking countries in the developing world to do just that – limit their economic development for environmental sustainability. And these developed economies are doing so while being largely responsible for the problem of global warming. At the same time, it is not the people in developed countries suffering from the worst effects of climate change. Rather, it is often the most marginalized and vulnerable people in developing countries that are paying the price of climate change and may face even more dire consequences in the future – the US, Canada, and the EU will not disappear with rising sea levels… Kiribati likely will.

Figure 9-19:

Source: https://flic.kr/p/o7WMAY Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Adam Cohn.

In turn, developing states are asking the developed economies to clean up their own mess and not download the cost to them. The world’s developed countries may argue that they cannot be held responsible for global warming and climate change because they were unaware of the dire consequences until relatively recently. However, this argument is weak since many of the consequences of globalization have been recognized for some time: King Edward I recognized air pollution as a problem in 1306, and global warming has been recognized since the 18th century. Beyond apportioning blame for historical practices, developing states have a stronger ethical claim: the world’s poor and marginalized are, and will increasingly be, adversely impacted by global climate change. The world’s developed economies have the means to mitigate if not address climate change, and they have those means because they created the problem in the first place. How can they ethically argue they do not have some responsibility to act if not lead to climate change mitigation? How is it not a human rights issue when climate change creates hurricanes, floods, droughts, and famines? How is it not a global crisis when such externalities will increasingly generate environmental crises, even environmental refugees?

The second ethics issue we will cover is the problematic nature of the global commons and the related issue of allocating emissions. The global commons refers to those spaces and resources owned by no one but accessible to all; think of the high seas, the atmosphere, or outer space. These are spaces that are not under the jurisdiction of a particular sovereign state and therefore are absent any legitimate authority to police it. This, in turn, incentivizes the overutilization and/or a lack of due diligence in maintaining it. Such resources are at risk of being rapidly depleted and/or polluted – this is called the ‘tragedy of the commons’. The simplest analogy to understand the tragedy of the commons is to think of pasture land owned by no one but accessible by all the nearby ranchers. The dominant logic would be to use the common pasture before using your own and to do so before others can deplete or pollute it. Further, there is little incentive to pay the cost of upkeep since everybody is using it. It is possible to govern the global commons, but it is difficult, expensive, and requires robust multilateral agreements. The Montreal Protocol is an example of such a successful agreement. It was possible to ban CFCs since it was relatively simple and alternatives existed. The Kyoto Protocol was a failed example, and it is not looking great for the Paris Agreement. Why? These are attempts to deal more broadly with global warming and climate change which is complex, expensive, and without concrete solutions. Part of the problem is that the atmosphere is part of the global commons. To mitigate climate change, there must be a general agreement that we must restrict CO2 emissions into the atmosphere. However, currently, it is impractical to stop all emissions immediately, which leaves the question of devising a system to allocate future emissions. Some argue we should scientifically determine the total allowable emissions levels and then divide those on a per capita basis. However, to do so would radically shift the economies and living standards of people around the world. Resource intensive societies like the US, Europe, Japan, and Canada would significantly restrict their emissions. At the same time, China and India could counterintuitively increase their per capita emissions. Further, an equal distribution of emissions per capita does not account for the difference between emissions associated with the necessities of life and those that are more of a luxury. Others argue that everyone should be entitled to the emissions necessary for life and that these may vary by climate and region. Anything above this minimum threshold should then be distributed equally on a per capita basis. Both proposals have ethical appeal, but they are equally vulnerable to the politics of international relations. Beyond a humanitarian appeal, how can the leaders of the US or EU be convinced to forego their standard of living and pay the economic costs of such a proposal? This is even more unlikely given the technological advantages held by MNCs in the developed world and the desire of developing states to access it.

Figure 9-20:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IMF_Developing_Countries_Map_2014.png#/media/File:IMF_Developing_Countries_Map_2014.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Bernardo Te.

Figure 9-21:

Source: https://flic.kr/p/qeEqhA Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Bernd Thaller.

Another approach would utilize a Rawlsian approach of helping the least well off. Those countries with the least developed economies and lowest living standards are given a greater relative share of emissions to foster development. While this again has ethical appeal, it still has the political hurdle of convincing the wealthiest and most powerful states to suffer for such distributive justice. A potential means to mitigate this tension would be to allocate emissions not by states but by MNCs and/or economic activity – to think of this as a problem for the global economy instead of pitting national economies against each other. Developing economies according to the IMF Developing economies out of scope of the IMF Graduated to developed economy Newly industrialized countries) However, such a globalist position would definitely encounter resistance from the growing number of populist and nationalist movements currently emerging worldwide. Contemporary global environmental policy recognizes: that the least developed economies will require exemptions from emission restrictions; that the most developed economies are going to by necessity help them develop through technology transfers and/or carry an environmental burden that is relatively higher than the least developed states. This may be rhetorically controversial, but most parties generally accept it. However, the biggest tension here is between the developed economies and the important emerging economies like China and India. From the perspective of countries like the US, granting concessions to countries like China and India is granting concessions to their economic rivals. The one key advancement of the Paris Agreement over the Kyoto protocol is bringing important states like India and China in. Yet, in the end, such advances may be for naught if the US defects in 2020. In the end, while it is generally recognized people have some claim to basic environmental rights, there is less agreement on what those rights entail, how they are to be protected, and who will pay the cost of ensuring them.

Figure 9-22:

Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/B32qg6Ua34Y Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Liane Metzler on Unsplash (https://unsplash.com/license).

The last ethical issue we will introduce is intergenerational responsibility. Currently, the consensus amongst the scientific community is that we are on an environmental trajectory with potentially disastrous outcomes for humanity. Let us take Canada, for example. If nothing changes and we have a business-as-usual attitude towards environmental policy, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has some dire predictions. They predict Toronto will increasingly see higher summer temperatures, over 51 days a year over 30 degrees. This poses significant problems, as we found out in the summer of 2018 with the 70 deaths in Quebec attributed to the heatwave. It is predicted there will be a 50-60% increase in costly weather events, from ice storms to wind storms. The Prairies and the west will have longer and more intense fire seasons as well as flooding. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, these trends are already here as Canada experienced more floods between 2010-2013 than the entire decade of the 1980s. The Maritimes will see more extreme storms and weather events. The arctic will rapidly warm, ending the Inuit way of life. As sea levels rise, communities on the coast will experience receding landmass. While the cost of weather-based events to insurers has traditionally been around 400 million dollars a year for decades, that average is now up to 1.8 billion dollars a year. Between 2010 and 2015, the Federal Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements program paid out more money than the previous 39 years combined. It is predicted that the cost of climate change could grow to 43 billion dollars a year by 2050, with a 5% chance this number could reach 93 billion dollars a year. What is clear is the cost of inaction will be dramatic both in terms of the economy and in terms of our quality of life. Through inaction, we are mortgaging, if not outright decimating, the welfare of future generations. Even more problematic is the idea of climate lag – the delay that can occur between action and impact. For example, the full effects of CO2 emissions are not felt immediately. Rather there is a delay between releasing emissions and the impact on the environment/climate, which means that we are not experiencing the impact of our actions today but rather our collective actions from the past. So even if we stopped all greenhouse gas emissions today, climate change would proceed, just slower.

This is deeply problematic from the perspective of intergenerational responsibility. Intergenerational responsibility adds a new facet to the ethics of environmental policy. It argues that we should not only be concerned about the impact of our policies on our own people and others outside our borders but also the descendants of each. It states that collectively, every generation does not inherit the earth but rather holds it in trust for the next generation. This is the core principle of sustainable development: the idea of meeting the needs of humanity today while protecting the needs of future generations. This raises questions of to whom we are or should be responsible towards? Do the demands for economic growth outweigh the future harm being generated? Is a consumption lifestyle ethical? Do we need a new smartphone every two years? What right do we have to mortgage today’s marginalized people’s quality of life and future generations for our conveniences?

- Watch the Ted Talk ‘Why Climate Change is a Threat to Human Rights’ by Mary Robinson

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- Why does Robinson argue climate change is a question of human rights?

- Why has President Tong of Kiribati had to buy land in Fiji?

- What does he mean by migration with dignity?

- What did Robinson discover when she explored why the people she met in Africa were saying ‘but things are so much worse now, things are so much worse”?

- Why did she feel this is unfair? (use the comparison of US/Philippines/Malawi GHG emissions)

- What is climate justice? Why is it a human rights issue?

- Do you believe Climate Change is, or perhaps should be, a human right?

Figure 9-23:

Source: https://pixabay.com/en/earth-world-globe-universe-space-683436/Permission: cc0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of photoshopper24.

As we have discussed in this module, there is an intimate relationship between global environmental issues and global citizenship. Environmental concerns have moved from the local to the global: from smog in major cities like London to global warming and climate change. The policies and actions of individuals and states are increasingly impacting people far outside their borders: the carbon-intensive nature of the most developed economies are connected to droughts in developing countries and even the possible extinction of low-lying island nations like the Maldives. Moreover, any meaningful attempt to address or mitigate issues like climate change will require a multilateral and/or global response. From a purely theoretical perspective, it is not problematic to argue that people have a right to habitable living space: to clean air, clean water, and non-polluted land… to be above water. Such rights extend beyond the direst cases as people should have a right to live without the fear of wildfires, drought, floods, and extreme storms if they are avoidable. Or at least people should expect the world’s leadership to reduce the likelihood of such damaging events from happening if at all possible. However, the sources of climate change are not restricted to particular states, which means that our rights to a clean environment are linked to obligations of others beyond our borders and vice versa. This suggests that environmental rights and obligations are by necessity a global versus a national issue. The problem arises with operationalizing these environmental rights obligations, given the lack of a defined polity greater than the state with authority to act. This brings us to the questions at the core of our course: what rights and obligations do we have to others beyond our borders? If they do exist, how are they defined? And by whom? Once defined, who is to enforce them and by what authority? While these questions are more theoretical when speaking of global citizenship, they become all too real when discussing global environmental problems and global warming and climate change. As suggested above, these are not theoretical questions but questions of the long-term sustainability of our way of life and for many, quite literally, questions of life and death.

Some academics and practitioners argue that global environmentalism may play an integral role in the discussion of global citizenship. As the argument put forward by the epistemic community on the issues of global warming and climate change begins to reach a critical mass in the general public, we may reach a tipping point with a consensus emerging that we are all in this together. That climate change must be addressed for practical and ethical reasons. That addressing climate change requires a supranational response. That a successful supranational response may spill over into other global concerns: poverty, inequality, and human security. This is much like the EU model of supranational governance: spillover from economic, to political, to social policy. If this were to happen, it is possible to see a viable route to global citizenship: from solving practical and functional problems to forming common identities and leading towards authoritative supranational political structures. However, this is a very tenuous chain of events that may well collapse in on the fragility of its own logic. There are many obstacles to be overcome: the resurgence of nationalism, the exploitation of class divisions, and/or the greed of the wealthiest and most powerful, which may seek to circumvent any global solutions to environmental problems. In the end, of all the global issues being faced today, the environmental questions of global warming and climate change offer the most immediate need for a meaningful conception of global citizenship. Yet, it is not clear whether even such an existential threat will overcome the inertia of the contemporary economic, political, and cultural systems operating at the global level.

- Read The Conversation Article “Caring about Climate Change: Global Citizens and Moral Decision Making” https://theconversation.com/caring-about-climate-change-global-citizens-and-moral-decision-making-44771

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- Why does Clive Hamilton argue that the greatest crime of our times is human influence on the environment?

- Why are cost and power important variables in addressing climate change?

- Why does the article suggest the climate policy driven by national actors will likely be weak and ineffectual?

- How might the narrative of Global Citizenship result in a different outcome?

- Why is the role of the media an important means to pivot the narrative towards a global frame?

- Why do the likes of Naomi Klein and NGOs like Oxfam think action on climate change may be a means to foster a more substantial conception of global citizenship?

- What do you think of this argument?

In this module, we have moved from the conceptual and theoretical to the functional and practical. Global environmentalism, and more specifically issues like global warming and climate change, are not only debates of political philosophy. They are not only debates about what rights and obligations we have with others outside our borders. They are questions of sustaining our way of life and questions of existential threat to many people around the world. They are practical problems that require functional solutions. In the first section of this module, we traced the rise of environmental consciousness. We noted that recognizing the negative impact human activity has had on the environment is not new. Almost every traditional society has noted the importance of the relationship between humans and nature, of achieving balance. We also noted how globalization’s economic, political, and cultural processes have made environmental questions increasingly global questions: from pollution, to nuclear power, to climate change. In section two, we noted how contemporary global environmental issues are increasingly becoming questions of mediating the global commons. In particular, climate change is connected to issues of emissions both historically and in the future. In trying to address such issues, we can see that these are not just technical questions but also questions of ethics and human rights. Who bears the greatest responsibility for the predicament we are in? How can we mitigate the problem while not creating more harm for the most vulnerable and marginalized? How do we create the political will to answer these questions? Finally, in the last section, we discussed how some see global environmentalism and, more particularly, the question of climate change as a possible route to meaningful global citizenship. The logic chain between the two starts with recognizing that meaningful solutions to climate change will be, by necessity, global. Such global action will foster greater global identification, which may lead to a spillover effect from functional solutions for practical problems to political action on a wide range of issues, including poverty, inequality, and human security. In so doing, global citizenship, as defined by a universal set of enforceable rights and obligations, will be furthered. However, as we noted in closing, this route to global citizenship faces many obstacles, and there is every chance it will not succeed. In the next module, we will turn to an even firmer theoretical claim to universality and even a more troubled history of application: human rights.

To contextualize the degree to which contemporary climate change is so abnormal in a historical context (I mean REALLY historical, even pre-historic), check out the timeline below… Give yourself a bit of time… It is long and detailed!

Figure 9-24:

Source: https://xkcd.com/1732/ Permission: CC BY-NC 2.5

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Air pollution: the introduction into the atmosphere of substance which may be harmful or poisonous. As related to issues like global warming and climate change, the introduction of greenhouses gales such as CO2 or CFCs are particularly problematic

Chernobyl nuclear reactor meltdown: a catastrophic nuclear accident that occurred in Chernobyl, 1986. Chernobyl is a Ukrainian city that was part of the Soviet Union at the time. The meltdown of the nuclear reactor sent radioactive plumes into the atmosphere for nine days that could be detected as far away as Finland, Iceland, Greece, and Turkey. The disaster created a strong backlash against nuclear energy and the creation of global anti-nuclear movements like Friends of the Earth.

Climate change: a change in global or regional climate patterns, in particular a change apparent from the mid to late 20th century onwards and attributed largely to the increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide produced by the use of fossil fuels

Cuyahoga river fire: captured global attention in 1969 when it was published in Times magazine. The river, stretching from Akron to Cleveland, has been one of the most polluted rivers in the US and has caught fire at least 13 times. The times article generated significant public debate and led to the creation of the Clean Water Act, the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

Deforestation: the act of cutting or destroying trees without replacing them, Deforestation often occurs for to accommodate agriculture, industrial, or urban use. It can put adverse pressure on species, leading to possible extinction of vulnerable groups, and can exacerbate environmental degradation through soil erosion and decreased CO2 absorption.

Developed economies: a sovereign state with a mature and stable economy, including an advanced technological infrastructure. There are various means to identify which states are considered developed: Gross Domestic Product (GDP), GDP per capita, and the Human Development Index.

Developing economies: a sovereign state with a less mature and potentially unstable economy with a lower ranking GDP, GDP per capita, and HDI. There will often be clear signs of economic dependence, poverty, and/or weak democratic credentials.

Environmental externalities: a by-product of an action or policy that is borne by the collective or someone other than the agent which undertook the action or policy. For example, a factory may produce CO2 emissions in to the atmosphere, generating air pollution that effects everybody, not just the producer

Environmentalism: can be a philosophy, ideology, or social movement which evaluates policies and actions through an environmental lens.

Free riders: those individuals and collectives which benefit from an action or policy while not either actively defecting from the framework and/or contributing to its realization

Friends of the earth: an international network of environmental organizations in 74 countries, formed to campaign for a better awareness of and response to environmental problems

Global commons: the earth's unowned natural resources, such as the oceans, the atmosphere, and space

Greenpeace: An organization devoted to environmental activism, founded in the United States and Canada in 1971. The NGO has employed passive resistance in opposition to commercial whaling, the dumping of toxic waste into the sea, and nuclear testing

Hole in the ozone layer: was identified over the Antarctic in 1984. The main culprit leading to the depletion of the earth’s ozone was identified as CFCs. The 1987 Montreal Protocol successfully reduced CFC emissions and has led to the whole in the ozone layer being repaired.

Industrial revolution: was a period of rapid industrialization during the 1700s and 1800s. It began in Great Britain, spread to Europe, and then globally. Key advances were made in mechanization, manufacturing, transportation, and communication technology. It has been a key driver of economic globalization.

Intergenerational responsibility: is defined by the obligation of the current generation to hold in trust the sustainability of the planet for future generations.

Kyoto protocol: is an international treaty agreed to at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, signed in 1997. It sought to create a carbon trading regime in order to address the problem of greenhouse gas emissions. It ultimately failed due to the defection of important actors like the US.

Mass consumer culture: is defined as a culture which privileges social status and activities which are based on the consumption of goods and services. It is often referred to as a ‘disposable culture’ where are goods have a built-in obsolescence.

Mass species extinction: the extinction of a large number of species within a short period of geological time.

Multilateral environmental agreements: an international environmental agreement singed by three or more state parties. However, it most often refers to agreements signed by the largest and most important stakeholders on a particular issue: the Montreal Protocol, the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement.

Rawlsian approach: is the adaptation or application of Rawls’ difference principle where by an action or policy is justified if it works to the advantage of the worst off

Silent spring: was written by Rachel Carson in 1962, this environmental science book documents the adverse effects on the environment of the indiscriminate use of pesticides

Sustainable development: economic development that is conducted without depletion of natural resources

The Montreal Protocol: is a 1987 international treaty designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of numerous substances that are responsible for ozone depletion

The Paris Agreement: is an agreement within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) dealing with greenhouse gas emissions mitigation, adaptation and finance starting in the year 2020

Tragedy of the commons: an economic problem in which every individual tries to reap the greatest benefit from a given resource. As the demand for the resource overwhelms the supply, every individual who consumes an additional unit directly harms others who can no longer enjoy the benefits.

UN Environment Programme: is the leading global environmental authority that sets the global environmental agenda, promotes the coherent implementation of the environmental dimension of sustainable development within the United Nations system, and serves as an authoritative advocate for the global environment

UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: was established as an epistemic community to provide scientific insight into climate change as well as its political and economic impact. It was established in 1988 and produces periodical assessment reports and special reports on climate change. The latest special report was released in 2018, with dire warnings if global warming reaches more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

References

BAN. 2018. “GPS Trackers Reveal More Canadian E-Waste Exported to Developing Countries — Basel Action Network.” BAN Champions of Environmental Health & Justice. http://www.ban.org/news/2018/10/10/gps-trackers-reveal-more-canadian-e-waste-exported-to-developing-countries.

Brown, Edith Weiss. 2013. “Intergenerational Equity.” In Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/e1421.

Demerse, Clare. 2016. “The Real Cost of Climate Change in Canada.” Policy Options Politiques. http://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/november-2016/the-real-cost-of-climate-change-in-canada/.

G, Matt. 2015. “A Brief History On Environmentalism — The Green Medium.” The Green Medium. http://www.thegreenmedium.com/blog/2015/9/2/a-brief-history-on-environmentalism.

Graber, Megan. 2016. “Would You Buy a Pre-Peeled Orange?: Whole Foods’s Pre-Peeled Oranges - The Atlantic.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/03/would-you-buy-a-pre-peeled-orange/472329/.

GreenFacts. 2017. “Scientific Facts on the Chernobyl Nuclear Accident.” GreenFacts: Facts on Healt and the Environment. https://www.greenfacts.org/en/chernobyl/index.htm.

Kaper, Hans. 2013. “The Discovery of Global Warming.” Mathematics of Planet Earth. http://mpe.dimacs.rutgers.edu/2013/01/19/the-discovery-of-global-warming/.

Leahy, Stephen. 2018. “Climate Change Impacts Worse than Expected, Global Report Warns.” National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/10/ipcc-report-climate-change-impacts-forests-emissions/.

Mackay, Caroline. 2017. “Engineering Failures: Chernobyl Disaster.” Engineering Institute of Technology. https://www.eit.edu.au/cms/news/industry/engineering-failure-chernobyl-disaster.

Montrouge, Philippa Duchastel De. 2019. “Media Briefing: Canada’s Plastic Waste Export Trends Following China’s Import Ban - Greenpeace Canada.” Greenpeace Canada. https://www.greenpeace.org/canada/en/qa/6971/media-briefing-canadas-plastic-waste-export-trends-following-chinas-import-ban/.

Mortillaro, Nicole. 2018a. “111 Million Tonnes of Plastic Waste Will Have Nowhere to Go by 2030 Due to Chinese Import Ban: Study.” CBC NEWS. https://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/china-plastics-import-ban-1.4712764.

———. 2018b. “Here’s What Climate Change Could Look like in Canada.” CBC News . https://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/climate-change-canada-1.4878263.

Parker, Laura. 2018. “China’s Ban on Trash Imports Shifts Waste Crisis to Southeast Asia.” National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/2018/11/china-ban-plastic-trash-imports-shifts-waste-crisis-southeast-asia-malaysia/.

The Canadian Press. 2018. “Quebec Says up to 70 People May Have Died in Connection with Heat Wave.” CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/heat-wave-death-toll-1.4740031.

The Climate Reality Project. 2018. “How Is Climate Change Affecting Canada?” Climate Reality. https://www.climaterealityproject.org/blog/how-climate-change-affecting-canada.

The Conversation. 2015. “Caring about Climate Change: Global Citizens and Moral Decision Making.” The Conversation Canada. https://theconversation.com/caring-about-climate-change-global-citizens-and-moral-decision-making-44771.

The Economist. 2018. “Exit the Dragon: A Chinese Ban on Rubbish Imports Is Shaking up the Global Junk Trade - Exit the Dragon.” The Economist 428 (9111). https://www.economist.com/special-report/2018/09/29/a-chinese-ban-on-rubbish-imports-is-shaking-up-the-global-junk-trade.

Weart, Spencer. 2012. “The Discovery of Global Warming [Excerpt].” Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/discovery-of-global-warming/.

Weyler, Rex. 2018. “A Brief History of Environmentalism - Greenpeace International.” Greenpeace International. https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/11658/a-brief-history-of-environmentalism/.

Supplementary Resources

- Arnold, Denis Gordon. The Ethics of Global Climate Change. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Gray, N.F. Facing Up to Global Warming: What Is Going on and How You Can Make a Difference? 1st Ed. 2015 ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015.

- Harris, Paul G. "Climate Change and Global Citizenship." Law & Policy30, no. 4 (2008): 481-501.