Why did black people don blackface in early American theatre? Explain the power dynamics of blackface worn by black performers.

African –American people were not accepted to perform on stage for most of the 19th The site of them was not tolerable to white audiences so in order for the white audience to feel more comfortable, they had to put on blackface as if they were Caucasian playing the role of a black person [2].

The interesting power dynamic of black face by black performers allowed the surrendering of the black performer’s power. Blackface was worn as a way to mock the African-American race.

How did ‘Shuffle Along’ reinforce or challenge:

The use of blackface in theater: The use of black face in reinforced or challenged “Shuffle Along” because of the way it was used. Black performers had to use blackface when performing to appear as a Caucasian performing as a black person. This showed that they surrendered their power because it mocked their own race.

The taboo of black sexuality: The observation of the white reaction to the song ‘Love Will Find a Way’ by Roger Matthews and Lottie Gee, the prima donna, was not what Les Walton, a journalist expected as they expressed more discomfort as opposed to rage or revolt [2]. White audiences did not want colored people to show too much affection from black individuals on stage. The audience would applaud if a coloured man serenades a girl at the window, but once he begins to resemble a Romeo, then he has crossed a line due to the fact black sexuality was dangerous to them [2].

Typical rhythms in musical theater: “Shuffle Along” challenged typical rhythms in musical theater because the “changes were often seemed as less rhythmical than mathematical” [2]. This made the pattern and rhythm much more difficult for dancers to follow.

Chorus lines: The chorus lines for “Shuffle Along” were mainly dance jazz, which was performed by stereotypical chorus girls. Josephine Baker was one of the performers on the chorus line.

Which song remains the most well-known from Shuffle Along? Had you heard this song before?

The song that remains most well-known from Shuffle along is “I’m Just Wild About Harry”. It is a song that most people can hum to and it was used as the theme song for Harry S. Truman’s presidential campaign in 1948 [2]. The song was written by African-Americans and was not used again till Barack Obama’s candidacy.

Explain what «patting Juba» meant, and who was Juba (the second Juba). Why is this story included, and how does it tie to our main story?

In the 1840s, P.T Barnum had a white kid in one of his shows named Diamond, the second Juba, who performed Juba or Juber dancing. “Patting Juba” is African dancing, plantation dancing. Juba was the inspiration behind the blacks and Irish-Americans creating tap. Juba was performed by you drumming on your body, slapping your chest and knees and the soles of your feet. Diamond would dance in blackface and Juba was seen as a black thing. Diamond ended up running away in 1841 due to him supposedly being dishonest with financial dealings before Barnum found out. Barnum was without his Juba dancer. He found the best in the world, a young boy that would come and perform for him in replacement of the second Juba. The first Juba was black and had to don the blackface [2]. This ties into our main story with how coloured individuals achieved small victories by donning the blackface.

Here is a video of the Juba Dance for you to have a better understanding what the Juba dance is:

Which claims about the historical significance of Shuffle Along are not exactly true? Who or what should actually claim this title?

Most of the claims that are made for “Shuffle Along” say that it is the first black Broadway show or the first successful one. Which isn’t exactly true because William’s and Walker’s show “Bandanna Land” of 1907-1909 was a black show performed over a decade before “Shuffle Along”. “Bandanna Land” should claim the first black successful Broadway show [2].

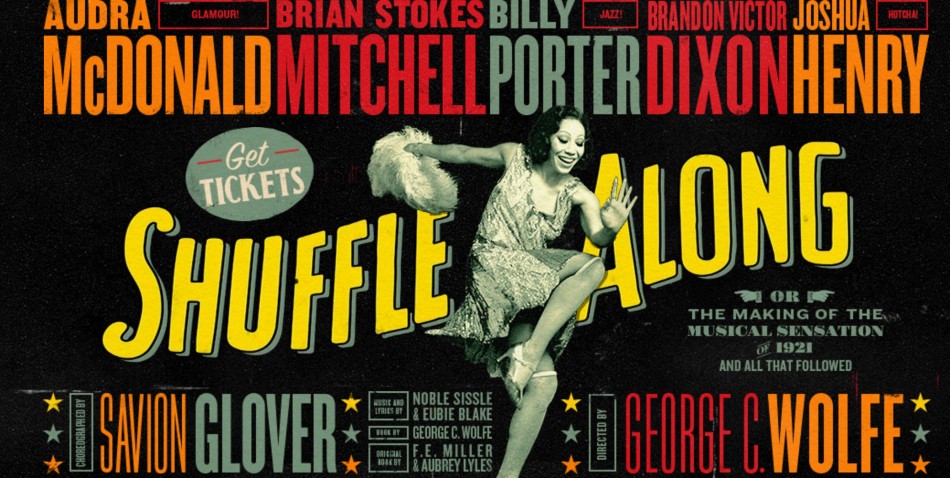

Explain the concept of the 2016 show and how it celebrated Shuffle Along. How does it approach the material?

There had been previous attempts in reviving “Shuffle Along” in 1932 and 1952 but both of them failed. George Wolfe, who started the recent revival portrayed it as not a revival, but a transformation. The new title for the show would be “Shuffle Along, or the Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed”. He would not redo the show but instead “he would tell the story of the original creators and cast and how they pulled it off” [2]. This approach would give a voice to various white outsiders during the original show. This was approached through things such as syncopation, dancing and singing which were preserved.

Here is a sample of the performance of “Shuffle Along” when it was performed in 2017:

What new information came to light for you when reading this article, and does it change your perspective on the conditions and challenges faced by early African American performers?

What I learned from reading this article was the challenges African Americans went through in order to do things that they loved. Black performers were treated unfairly and went through many difficulties such as performing through blackface and the discomfort that was expressed upon them when too much affection was shown within their performance.

Look back to the section entitled ‘Minstrelsy and American Popular Music’ in your textbook (page 28), specifically the paragraph that begins “Minstrelsy would give blacks…” – in light of the article, do you feel this paragraph (or the textbook in general) offers a fair perspective on blackface in America? Why or why not?

After reading his section in the textbook, I feel like the textbook does not portray blackface and minstrels in light to what has occurred. It portrays Minstrels as more of a positive thing that contributed to four important firsts that influenced the coming generations of popular music:

“1. It was entertainment for the masses.

2. It used vernacular speech for music.

3. It created a new genre of music by synthesizing middle-class urban song and folk music.

4. It was the first instance of a phenomenon in American popular music that has continued to the present day: that of invigorating and transforming the dominant popular style through the infusion of energetic, often danceable music [1]”.

From the wording of the textbook and how it explains Minstrels, it gives them a positive outlook and that Minstrels were important. It portrays blackface as a positive occurrence. In my opinion, blackface was not a positive portrayal and offers up an unfair perspective of how it is viewed in America.

Works Cited:

[1] Campbell, Michael. 2012. Popular Music In America: The Beat Goes On. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Schirmer.

[2] Sullivan, John. 2016. “‘Shuffle Along’ And The Lost History Of Black Performance In America”. Nytimes.Com. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/27/magazine/shuffle-along-and-the-painful-history-of-black-performance-in-america.html?mcubz=1

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/A-309976-1437588951-1632.jpeg.jpg)