Hi, my name is Lauren Worobec and I am here to talk about Gertrude “Ma” Rainey and her impact on the music and blues era.

Ma Rainey was born Gertrude Pridgett on April 26th, 1886 in Columbus Georgia. She left home as soon as she was able to at the age of fourteen to become a vaudeville performer.(NYTimes n.d.)She was known as the “Mother of the Blues” and was recognized as the first great female blues vocalist. Gertrude married a comedian and songster named William Rainey at the age of eighteen. The two of them were then known as Ma and Pa Rainey. The couple traveled all around the south performing in tent shows and cabarets. She is also no stranger on the vaudeville stages. The couple sang, danced in their performances. The Rainey’s toured with Fat Chappelle’s Rabbit Foot Minstrels and eventually were “Assassinators of the Blues”

After separating with her husband, Pa Rainey in 1916 and then toured with her own band. She then released her first song “Moonshine Blues” with Lovie Austin and “Yonder Comes the Blues” with Louis Armstrong. Ma Rainey’s songs were different from other blue singers because of her experiences as a black woman from the south brought a new aspect to her songs. Her songs were about heartbreak, promiscuity, drinking binges, odyssey of travel, the workplace, prison road gang and magic and superstition.

Ma Rainey was known for wearing long beautiful gowns, covered with diamonds. Always wearing necklaces of gold and had gold in her teeth that would sparkle on stage. One memorial moment for Ma Rainey was when she stepped on stage with an ostrich feather in one hand and a gun in the other. (atlasobscura n.d.) Hre on stage was over powering and filled with confidence. After her mother and sister passed away, she retired and bought two entertainment venues. She carried out she years in Columbus until she passed away on December 22nd, 1939. (Biography n.d.)

Ma Rainey was one of the first black diva in history. She then took Bessie Smith under her wing and helped and coached her in her singing. Bessie toured with Ma, where Ma was a get influence in her songs and singing. They were both recorded by 1923. (NYTimes n.d.)Both of these young singers were openly bisexual.

Ma Rainey had a large influence on the American blues. She was also a role model in the African American womanhood. She helped establish the world of women in the blues industry. She was acknowledges her accomplishments when she was inducted into the Blues Foundation’s Blues hall of Fame, the Rock and Roll hall of Fame, the Georgia Music Hall of Fame, and Georgia Woman of Achievement.

Some challenges that Ma Rainey faced was, she was the first black woman to really sing the blues and have such an influence on the era. Ma Rainey has also expressed and stated that lesbian sexuality and this was very uncommon at this time. She overcame this obstacle by keeping he music the most important and not letting what other people say about her influence what she does.

Several artists have covered her songs including, Ray Charles, Elvis Presley and Cher. Her name is also mentioned by Bob Dylan in his song Tombstone Blues. (CBC n.d.)

Here is a singer Alana Bridgewater who sang a cover of one of Ma Rainey songs. She is still a role model today and has fans who love and admire who she was and what she did for music.

I am a dancer and I am trained in CDTA (Canadian Dance Teachers Association) in tap. In that training, the basic tap steps where invented and started on the stages in Vaudeville. There are steps like grapevine, time steps shim sham shimmy. It is nice to hear the music that would have been sung for the vaudeville dancers and how those tap steps would be danced to that music.

This song is about a love story and an unfaithful partner. It was very popular in 1925, and multiple artists recorded their own version years later. See See Rider was seen as a song about a easy woman, or “easy rider” about a woman who is experienced in sexual encounters, or a woman who has been married multiple times. In Ma’s interpretation is referring to the male in the love story. Experiencing that he is the unfaithful one in the relationship.

Moonshine Blues was one of her early written songs. It demonstrated the smooth, relaxed blues that she was commonly known for. It was seen that the song was about drinking and the effects that alcohol has on a man.

Don’t Fish in my Sea is either reflecting on a relationship with her father or an adulterous male. She uses powerful words to paint a detailed picture of the relationship and the story line.

Works Cited

n.d. Biography.https://www.biography.com/people/ma-rainey-9542413.

n.d. CBC.https://www.cbc.ca/radio/q/tuesday-may-15-2018-mary-steenburgen-james-bay-and-more-1.4662028/gateway-to-the-music-of-blues-singer-ma-rainey-1.4662156.

n.d. NYTimes.https://www.nytimes.com/1984/10/28/theater/the-real-ma-rainey-had-a-certain-way-with-the-blues.html.

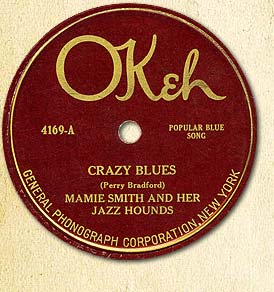

The song “Crazy Blues” was composed by Perry Bradford and later recorded by Okeh Studios on August 10, 1920 (Garner, 2018). This song sold one million copies within the first six months of its release, which quickly made Mamie Smith a household name. Although this song does not fully classify as a blues song, but rather a blues-influenced popular song, it is still widely considered to be the first blues recording in history (Campbell, 2013). The outstanding success of this song sparked a revolution in the music industry as other music producers began searching for female African American singers to capitalize on the newly-discovered “

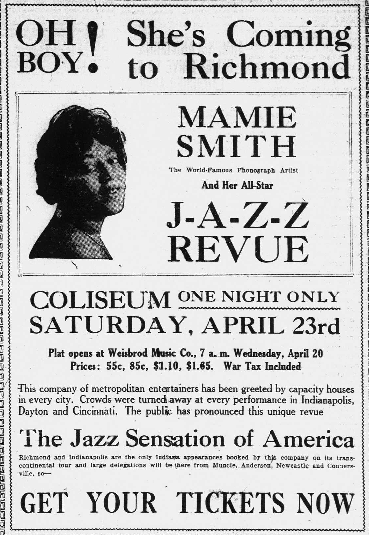

The song “Crazy Blues” was composed by Perry Bradford and later recorded by Okeh Studios on August 10, 1920 (Garner, 2018). This song sold one million copies within the first six months of its release, which quickly made Mamie Smith a household name. Although this song does not fully classify as a blues song, but rather a blues-influenced popular song, it is still widely considered to be the first blues recording in history (Campbell, 2013). The outstanding success of this song sparked a revolution in the music industry as other music producers began searching for female African American singers to capitalize on the newly-discovered “ Mamie was said to have been glamorous and display her wealth through her gorgeous clothing and jewelry (Garner, 2018). It could be assumed the white Americans were able to forget about their distasteful thoughts towards black Americans when it came to Mamie because she displayed a high-class persona that was associated with the dominant white culture.

Mamie was said to have been glamorous and display her wealth through her gorgeous clothing and jewelry (Garner, 2018). It could be assumed the white Americans were able to forget about their distasteful thoughts towards black Americans when it came to Mamie because she displayed a high-class persona that was associated with the dominant white culture.