Hello class,

This blog response is to module 2 question 2 “On Boxing and Music” in which I aim to discuss the historical context and key individuals from the early 1900s discussed in Michael Walsh’s Smithsonian article. Next I will discuss the contrast between prevailing issues in society as reflected in the popular music of the time as discussed in Mark Harris’ Vulture article. Each writer describes specific periods in history, both with a corresponding boxing match and example of popular music. From a significance standpoint in terms of societal impact, these bouts are polar opposites. Jack Johnson vs. Jim Jeffries in 1910 was dubbed the “fight of the century” as it took place against a backdrop of intense racial tensions between the white (Caucasian) and black (African) Americans. Whereas Conor McGregor vs. Floyd Mayweather in 2017 was a distracting spectacle and unabashed cash grab, perhaps a fitting analogy for the spectacle taking place on the US political landscape. Similar to sports, the popular music of the time can also reflect issues in society. In 1910, music composer and pianist Scott Joplin was desperately trying to legitimize his ragtime style of music against dismissive preconceptions, and evolve his music into higher art forms. In 2017, Taylor Swift is fighting back against critics and enemies, while attributing ownership of her behavior onto others. Both these musical examples likewise reflect different societal contexts, which will be discussed below.

In Pursuit of Racial Equality–two philosophies

On January 1st, 1864, President Lincoln declared that all black slaves in the US were free. However, historically entrenched racism persisted within society leading to racial segregation “Jim Crow” laws. Though free from slavery, the black population were not fully free to enjoy equal rights, liberties, and prosperity as the white population. The early 1900s would see two outspoken individuals, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, become leaders for black social uplift movements.

Booker T. Washington (1856-1915)

Image courtesy of biography.com(1)

Washington was born into slavery, and throughout his whole life he struggled to attain an education. As an adult he earned a scholarship to a vocational skills school, thus shaping his appreciation for industry (1). Likewise, Washington advocated for fellow black people to become educated in trades skills. In Washington’s famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech in 1895, he stated “[o]ur greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life” (2). In essence Washington asked that black people persevere through racial discrimination, all while proving their own usefulness by becoming more educated in their trades.

William Edward Burghardt (W.E.B.) Du Bois (1868-1963)

Image courtesy of biography.com(3)

Du Bois was born into freedom and able to freely attend schools where he frequently found enthusiastic and helpful teachers and mentors. Du Bois would later become the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard (3). Unlike Washington’s social compromise urgings, Du Bois pushed for blacks to push back against discrimination to gain racial equality. However, instead of Washington’s mass population approach, Du Bois believed a smaller group of highly educated individuals in broad liberal arts, whom he called “the Talented Tenth”, would act as leaders in black society to uplift the rest (4).

Joplin and Johnson–black icons during racial segregation

By the early 1900s, pianist and composer Scott Joplin, dubbed the “King of Ragtime”, had moved to New York in 1907 as he developed his compositional ability to both legitimize ragtime music and incorporate it into his own original opera. Jack Johnson meanwhile had just shocked the world in 1908 when he became the first African American heavyweight boxing champion of the world and was slated to soon fight the undefeated former champion Jim Jeffries. Joplin and Johnson had both reached unprecedented levels of success in their careers, but both had profoundly different effects on the black social uplift movement taking place.

Scott Joplin (1868-1917)

Image courtesy of biography.com(5)

By the age of 26, Joplin had moved to Missouri where he toured around with local bands to earn money to seriously study music and composition (5). Joplin would introduce a more classical interpretation of ragtime music, which was often denigrated as immoral and low class music, and he gradually gained popularity among the circuit of local clubs he worked at (6). In 1889 Joplin would sell his most famous composition, the Maple Leaf Rag, which went on to become the first instrumental to break one million sheet music sales by 1914 (6).

With a steady stream of royalties income off of Maple Leaf Rag, Joplin was able to devote his time to teaching his ragtime style and to writing his operas. Despite ragtime gaining popularity, it was still associated with immoral and tawdry behavior associated with the disreputable venues ragtime was often played in (7). The opera was a European carryover considered to be entertainment for the upper class in society. Joplin relentlessly pushed for his opera to be realized, but it only went as far as a poorly received initial run through in 1915, where sadly Joplin could not afford costumes, sets, or an orchestra. With his opera rejected Joplin slipped into a depression, concurrent with his already deteriorating mental and motor ability as a result of syphilis, and he soon passed away in 1917 (6).

Only after Joplin’s death would his name gain wide acclaim as ragtime music experienced a renaissance. Several of Joplin’s rags were significant pieces of an Oscar winning soundtrack for the film Sting, which itself won the best picture award in 1974. A whole new generation of listeners were being exposed to Joplin’s music, but in higher art forms outside of the red light districts. Joplin’s opera Treemonisha was also produced, thus bringing his dream to fruition when it opened on Broadway in 1975. Joplin was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer prize for his contribution to American music in 1976 (6).

Jack Johnson (1878-1946)

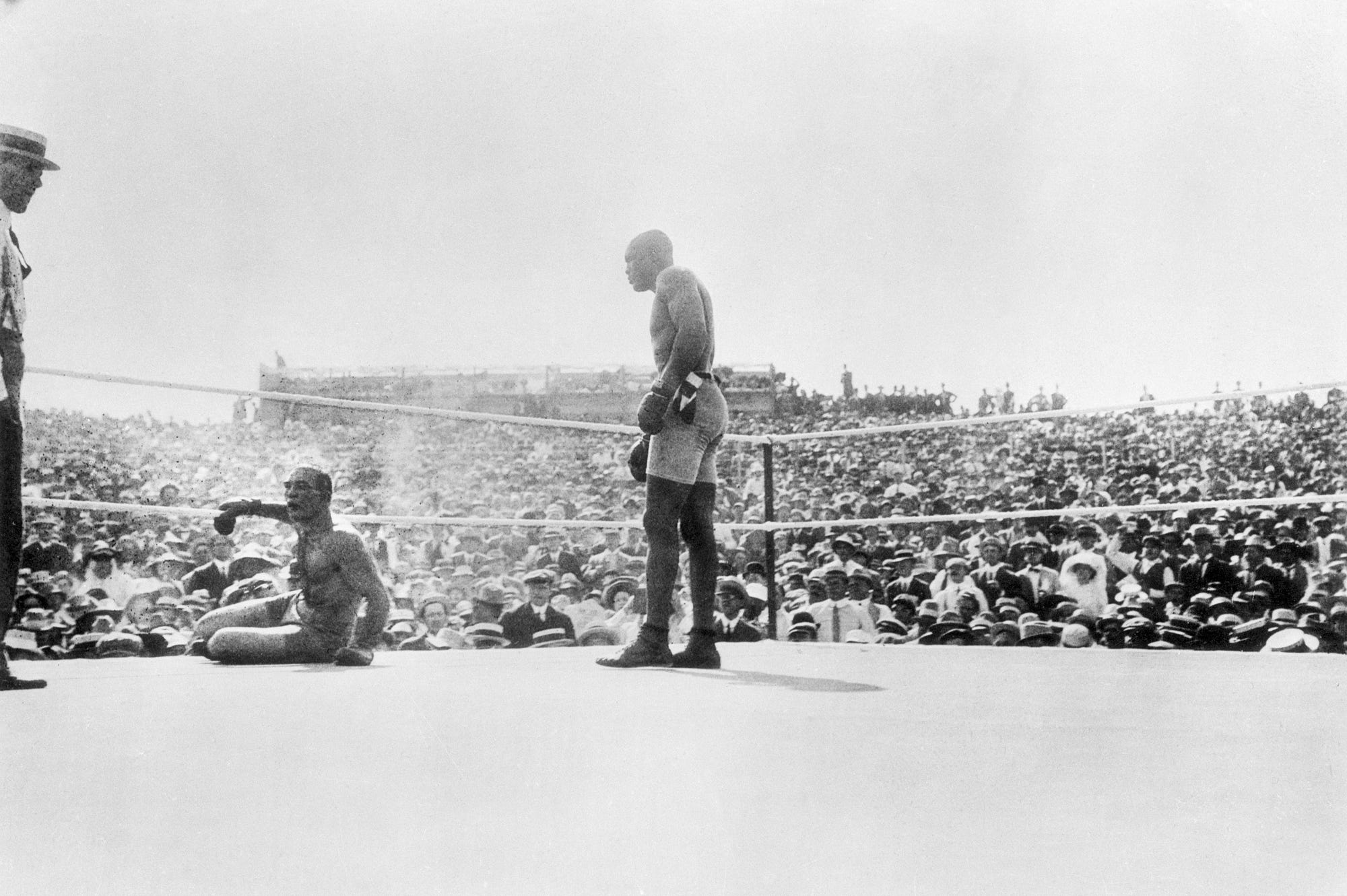

Johnson vs. Jeffries 1910 in Reno, Nevada. Image courtesy of Timeline.com (8)

In the boxing world, Johnson seemingly exploded onto the scene out of obscurity. As a black fighter, Johnson had only fought on the colored fighter circuit where he fought more than 50 bouts and was a dominant champion. When Johnson finally entered the ring with white boxers, he quickly rose the rank of contenders in just over a year before capturing the heavyweight title in 1908. Johnson’s victories and subsequent title defenses was a stark shock to all the preconceptions of white superiority over black athletes. On top of breaking trough the status quo, Johnson also earned public scorn from his extravagant lifestyle and romantic relationships. Johnson enjoyed the fruits of his labor by flaunting expensive clothing and vehicles, but even more unsettling to his predominantly white critics was he dated white women. Desperate for an answer to Johnson, the undefeated former champion Jim Jeffries was compelled back out of retirement.

Jeffries was older than Johnson by seven years, and he had been retired for six years as a farmer before they fought in 1910. To the shock of the 20,000 spectators Johnson dominated, from start to finish, the elder retiree Jeffries. What ensued were race riots across America with hundreds injured and 26 killed within the day, all predominantly black (8). That bout would serve as the peak of Johnson’s career, which then proceeded to tailspin as he was targeted for arrest pertaining to some of his past romantic dalliances. Whether if those charges were racially-motivated or not, Johnson’s flaws as a serial abuser and philanderer with women made it difficult to defend his character. As such, Johnson’s impact on black social progress was not through the manner he carried himself, but through the unprecedented novelty of his achievement that everyone was conditioned to believe was impossible.

Joplin and Johnson in perspective

Joplin best adopted Washington’s philosophy of perseverance against discrimination, while working towards translating his style of music into a higher art form that would hold societal value. Washington’s message is strongly conveyed in Joplin’s opera’s title character, Treemonisha, a young black woman who uplifts her village from oppressive lies and superstitions through education and enlightenment. Treemonisha exudes a quiet patience as she convinces her fellow villagers against seeking revenge against their oppressor, but instead to continue “marching onward” and to “walk slowly, talk lowly” as the opera closes (9). This final message conveys Washington’s idea of black society’s acceptance of oppression being intertwined with their progress as they strive to earn trust and equality through patience and education.

Johnson meanwhile embodied Du Bois’ philosophy of becoming one of the elites within his population. Although not in the classical sense of being highly educated, Johnson honed an elite fighting ability that would provide him the same platform as white fighters. Johnson’s fights were shows of defiance as he constantly challenged oppressive forces whether they be from tens of thousands of angry fans, or even the government charging him with illegal acts. Johnson’s accomplishments were the first stepping stones for future black athletes that now saw the myth of white superiority debunked. One of the greatest boxers in history, Muhammad Ali, who was influenced by Johnson aptly summarized him as being a “bad, bad black man”, which Johnson was ultimately portrayed as for going against the norm.

Societal reflections: music of the past and today

McGregor vs. Mayweather in 2017 was in essence an on-demand novelty act. In an era where the biggest action movies were collaborations of the most popular names and characters, it only seemed fitting that the most outspoken names in combat sports were paired together. Besides the crossover appeal, this bout holds no significant social impact. While on the popular music front, Taylor Swift’s “Look what you made me do” is a montage of her many brand and persona changes, as well as being an overall diss track to various celebrities and critics that have feuded with Swift. Harris’ Vulture article opines that Swift’s song encapsulates the modern era in which society expresses apathy towards substantive character, but is instead obsessed with superficial public image and one’s celebrity. Furthermore, Harris points out a contributing problem towards this apathy as being a cavalier attitude towards constantly changing one’s own narrative to placate others. For music artists, reinventing oneself is not new, but it seems today there is almost an annual retooling of one’s style to fit the current mainstream sound.

As a reflection of eras, Joplin’s ragtime songs were an example of the struggle of black integration into white society as we hear ragged off time African-inspired syncopation among the regular marching beats. Today’s music reflects how easily distracted we are with the sheer bombardment of media content, news, phone apps, etc., but it also shows the power of mass, anonymous opinions that are openly shared across the internet to the point that content producers have a direct vein to what consumers like or dislike. Music of the early 1900s reflected struggle to stand out, while today’s is reverse consumerism of demand and supply where producers will give you what you want to hear. Thus, the manner in which we digest music and perceive artists today is in constant flux depending on what the mainstream demand is at the time. As a result, artists now put out wide ranging albums with songs encompassing multiple styles and genres to appease a diverse demographic. In summary, the musical reflection of society today is everything on demand.

Endnotes

- A&E Television Networks. “Booker T. Washington Biography” The Biography.com website, March 1, 2018., Accessed July 16, 2018. https://www.biography.com/people/booker-t-washington-9524663

- “Booker T. Washington Delivers the 1895 Atlanta Compromise Speech.” HISTORY MATTERS – The U.S. Survey Course on the Web. Accessed July 17, 2018. http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/39

- A&E Television Networks. “W.E.B. Du Bois Biography” The Biography.com website, January 19, 2018., Accessed July 16, 2018. https://www.biography.com/people/web-du-bois-9279924

- “W.E.B. Du Bois and the Rise of Black Education.” AUC Woodruff Library Digital Exhibits. Accessed July 27, 2018. http://digitalexhibits.auctr.edu/exhibits/show/seekingtotell/education

- A&E Television Networks. “Scott Joplin Biography” The Biography.com website, January 19, 2018., Accessed July 17, 2018, https://www.biography.com/people/scott-joplin-9357953

- “Scott Joplin (c. 1868 – 1917).” Moses Austin – Historic Missourians – The State Historical Society of Missouri. Accessed July 27, 2018. https://shsmo.org/historicmissourians/name/j/joplin/

- Michael Campbell, Popular Music in America The Beat Goes On Fourth Edition, Boston MA, USA, Clark Baxter, 2013, p. 59-60

- Reimann, Matt. “When a Black Fighter Won ‘the Fight of the Century,’ Race Riots Erupted across America.” Timeline. March 24, 2017. Accessed July 27, 2018. https://timeline.com/when-a-black-fighter-won-the-fight-of-the-century-race-riots-erupted-across-america-3730b8bf9c98

- Rachel Lumsden. “Uplift, Gender, and Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha.” Black Music Research Journal 35, no. 1 (2015): 41-69. https://muse.jhu.edu/ (accessed July 19, 2018).

1. Campbell, Michael. Popular Music in America: The Beat Goes on. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Schirmer Cengage Learning, 2013, 18.

1. Campbell, Michael. Popular Music in America: The Beat Goes on. 4th ed. Boston, MA: Schirmer Cengage Learning, 2013, 18.