Despite the outright parody of black culture involved in almost any performance involving blacks in the late 18th century to the early 19th century, black performers embraced it. Shuffle Along, a musical which ran between 1921 and 1922, became integral to the success of black performers. It appealed to audiences in that it balanced the stereotypes enhanced by minstrel shows with respectable use of humour and drama, entertaining people in the full round. (1)

Tiger Woods once stated, “If you can’t laugh at yourself, who can you laugh at?” (2). The black performers in minstrel shows and other performances preceding and including Shuffle Along adhered to a similar ideal — they at first faced competition with whites who used blackface, but once the blacks themselves began to — rather redundantly — use blackface and perform their own minstrel shows, audiences were far more attracted to it, as they found it to be more authentic. (1) In the same way that many comedians today use embarrassing stories and perhaps overly honest anecdotes to make people laugh, blacks would use self-deprecation to relate to their audience while entertaining them, which proved to be a success.

Shuffle Along challenged what was acceptable in black performances and what was not. It explored new concepts previously considered unacceptable to whites, such as romance. It was a baby step for the world of coloured performers. Previously, romance was strictly for white performances only, but using the balance of humour and drama, the black actors were able to express themselves in a surprising, although slightly uncomfortable, way. As it had never been seen before, naturally white audiences were taken aback, unsure what to think of it. Though the response from whites was lukewarm, they were no longer cold, and today most can say that — at least in North America -people have thoroughly warmed up to it.

The music in Shuffle Along was difficult to follow — that is, to dance along with. Every beat was full of footwork, leaving only the most skilled of tap-dancers able to fit all the moves in. These rhythms were another shock to audiences as they stood out from other music at the time; they almost couldn’t believe that the music they were hearing could possibly exist, let alone anyone being able to dance along with it. (3)

Another feature of the influential musical was the use of a chorus line. The chorus line in Shuffle Along opened a door to talented coloured dancers looking for a bigger role, a true expression of themselves. Josephine Baker was among the 16 girls hired for the chorus line. She was actually initially hired on as a dresser, but upon one of the chorus girls getting sick, Josephine saw an opportunity and took her place, performing in the musical until the end of its tour in 1922. (4) Her energetic, humourous, and overall eye-catching dance moves were a display of unfiltered enjoyment and set off the beginning of her successful career. Some of her moves can be seen in the following video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H46uf5-Way0

“I’m Just Wild About Harry” has become rather well-known in popular music. It is a bouncy tune that has a steady beat with a flowing, syncopated sung melody. This, of course, may depend on song interpretation by the performer, but most versions of it involve an enthusiastic singer who doesn’t feel the need to adhere strictly to the beat of the rhythm section. It is a song I have passively heard before, but never really tuned into the lyrics or really tried to appreciate it before. Knowing now its origins, I can certainly appreciate the skill of the performers and what the performance in itself means to the history of popular music.

African-American slaves created a type of dance which is referred to as “patting juba”. It is usually done to an irregular beat, using 3/4 time signatures with complicated rhythms. Two men dance in the centre of a circle of other men, improvising their moves as they respond to the clapping beats provided by the participants in the circle. (5) Percussive sounds are a large part of juba dancing; often participants slap, clap, or smack various parts of their own bodies to quickly and energetically express their moves. This became the foundation for tap dancing. P.T. Barnum, a historic showman of the 19th century, had a juba dancer in his shows. Despite juba dancing’s heavy influence from black dancers, this Irish kid was white. However, he left Barnum’s show, leaving the showman to find a new juba dancer. This ended up being a blessing in disguise — a new dancer came along, who even came to be known as Juba due to his high level of skill for the dance. The only issue was that Juba was black, so white audiences were not as willing to accept him. Juba and the first juba dancer would complete against one another, though, and as Juba rarely lost, he gained a reputation. Barnum even attempted to paint the original juba dancer in blackface to mimic Juba’s appearance, but audiences still rejected him in favour of the more talented Juba.

Though Shuffle Along has been called one the first successful black productions, it is not necessarily the case. The gentlemen who produced the musical actually had other black productions before Shuffle Along that were just as, if not even more, successful. For example, their 1907 production Bandanna Land played at the Majestic Theatre, whereas Shuffle Along was played at the Sixty-Third Street Music Hall, a much less established production house.

The 2016 rendition of Shuffle Along, that is, Shuffle Along in no way attempts to perfectly recreate the original. Instead, it is a revival of its memory, demonstrating the significance of the original production including its black cast members and creative minds. It is a show of appreciation and a reminder of what black performers went through to open the doors to talents of all colours today.

As a white person myself, I haven’t ever really considered how black performers made their way into popular culture. I’ve been given imagery of black men from the slavery days playing some form of blues on old banjos, like you see in literature such as Huckleberry Finn, but I had never really considered how the transition from the ‘lonely, unliberated blues-black’ to the hearty black jacks-of-all trades who dominate many genres of popular music came to be. Having read this article, I am more aware of the difficult process black performers had to break through to become fully accepted in pop culture.

Reading what the Campbell textbook has to say about black performance and minstrelsy, I would say that blacks are well credited for their contributions to popular music and culture as we know it. Without them, we wouldn’t have blues, jazz, R&B, or even rock and roll as we know it — popular music itself would have taken an entirely different path, which if we were to hear it, would be totally unrecognizable.

Sources Cited

- “Stage 1920s III: Black Musicals.” Cabaret History I, www.musicals101.com/1920bway3.htm.

- “A Quote by Tiger Woods.” Goodreads, Goodreads, www.goodreads.com/quotes/56461-if-you-can-t-laugh-at-yourself-who-can-you-laugh.

- Reside, Doug. “Musical of the Month: Shuffle Along.” The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library, 27 Oct. 2015, www.nypl.org/blog/2012/02/10/musical-month-shuffle-along.

- League, The Broadway. “IBDB.com.” IBDB: Internet Broadway Database, www.ibdb.com/broadway-production/shuffle-along-1921-9073.

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Juba.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædiaa Britannica, Inc., 27 Nov. 2014, www.britannica.com/art/juba-dance.

- Gardner, Elysa. “Broadway Gets Another Exuberant History Lesson in ‘Shuffle Along’.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 29 Apr. 2016, www.usatoday.com/story/life/theater/2016/04/28/broadway-gets-another-exuberant-history-lesson-shuffle-along/83593084/.

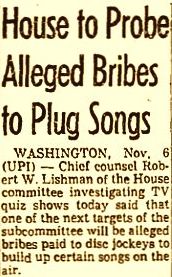

‘Payola – The paying of cash or gifts in exchange for airplay’. [2] This is the broad definition of the term ’Payola’ but what this definition lacks is the substance that makes the word so memorable to so many within the music industry. The Payola scandal is one of the most significant events in the introduction of popular music into the mainstream the influence it had on future music and the music that was deemed popular at the time was all influenced by this particular event and it may have very well changed the course of music history. “Payola” is a contraction of the words “pay” and “Victrola” (LP record player). [2] This basically means hat whoever was in changed could be bribed into playing songs that were not on the set list which gave more exposure to the artists that were in need of radio play to kick off their careers.

‘Payola – The paying of cash or gifts in exchange for airplay’. [2] This is the broad definition of the term ’Payola’ but what this definition lacks is the substance that makes the word so memorable to so many within the music industry. The Payola scandal is one of the most significant events in the introduction of popular music into the mainstream the influence it had on future music and the music that was deemed popular at the time was all influenced by this particular event and it may have very well changed the course of music history. “Payola” is a contraction of the words “pay” and “Victrola” (LP record player). [2] This basically means hat whoever was in changed could be bribed into playing songs that were not on the set list which gave more exposure to the artists that were in need of radio play to kick off their careers. “In 1959, Alan Freed, the most popular disc jockey in the country, was fired from his job at WABC after refusing to sign a statement that he’d never received payola to play a record on the air. For most of America, the word payola was a new one. But for anybody in the music business, it was as old as a vaudevillian’s musty tuxedo” [1]. Although not new to many within the industry payola became an important part of the late 50’s and into the early 60’s with Alan Freed standing trial along with another popular DJ at the time Dick Clark both decreed their innocence in receiving payments to play certain songs. “It was Freed who ended up taking the fall for DJs everywhere” [1]. The question is why did Alan Freed take the brunt of these accusations when Dick Clark among many other DJ’s at the time were guilty of the same thing? Alan Freed had a reputation of being more outspoken “Freed was abrasive. He consorted with black R & B musicians. He jive talked, smoked constantly and looked like an insomniac” [1].

“In 1959, Alan Freed, the most popular disc jockey in the country, was fired from his job at WABC after refusing to sign a statement that he’d never received payola to play a record on the air. For most of America, the word payola was a new one. But for anybody in the music business, it was as old as a vaudevillian’s musty tuxedo” [1]. Although not new to many within the industry payola became an important part of the late 50’s and into the early 60’s with Alan Freed standing trial along with another popular DJ at the time Dick Clark both decreed their innocence in receiving payments to play certain songs. “It was Freed who ended up taking the fall for DJs everywhere” [1]. The question is why did Alan Freed take the brunt of these accusations when Dick Clark among many other DJ’s at the time were guilty of the same thing? Alan Freed had a reputation of being more outspoken “Freed was abrasive. He consorted with black R & B musicians. He jive talked, smoked constantly and looked like an insomniac” [1].  Whereas Dick Clark had a different persona which was reflected by his peers, “Clark was squeaky clean, Brylcreemed handsome and polite” [1]. The fate of these two major players in the payola scandal took two different paths “Freed’s friends and allies in broadcasting quickly deserted him. He refused to sign an affidavit saying that he’d never accepted payola. WABC canned him, and he was charged with twenty-six counts of commercial bribery. Freed escaped with fines and a suspended jail sentence. But he died five years later, broke and virtually forgotten” [1]. Dick Clark’s fate was much different which leads people to believe that Alan Freed took the fall for other DJ’s including Clark, “Dick Clark had wisely divested himself of all incriminating connections (he had part ownership in seven indie labels, six publishers, three record distributors and two talent agencies). He got a slap on the wrist by the Committee chairman, who called him “a fine young man”. [1]Dick Clark was clearly the largest proprietor of the payola scandal having for a DJ to be that heavily involved as an owner in those businesses he had to have been doing well financially and subsequently had a major influence on those artist’s who were looking to make it big. This marked the first time that music within the African American community got some national attention during the payola scandal Alan Freed “first played Rhythm & Blues (R & B, or “race music”) in 1951. Until that time, the music remained largely in the black community”. [4] Until this point the music that was primarily known in the African American communities had some exposure on some mainstream radio stations because of guys like Alan Freed, however the principle of exploiting these musicians and using the advantage of their position to gain some financial power at the expense of the lack of acceptance of African American’s can be considered a little disingenuous because of the situation even though these musicians had major talent which led into the birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

Whereas Dick Clark had a different persona which was reflected by his peers, “Clark was squeaky clean, Brylcreemed handsome and polite” [1]. The fate of these two major players in the payola scandal took two different paths “Freed’s friends and allies in broadcasting quickly deserted him. He refused to sign an affidavit saying that he’d never accepted payola. WABC canned him, and he was charged with twenty-six counts of commercial bribery. Freed escaped with fines and a suspended jail sentence. But he died five years later, broke and virtually forgotten” [1]. Dick Clark’s fate was much different which leads people to believe that Alan Freed took the fall for other DJ’s including Clark, “Dick Clark had wisely divested himself of all incriminating connections (he had part ownership in seven indie labels, six publishers, three record distributors and two talent agencies). He got a slap on the wrist by the Committee chairman, who called him “a fine young man”. [1]Dick Clark was clearly the largest proprietor of the payola scandal having for a DJ to be that heavily involved as an owner in those businesses he had to have been doing well financially and subsequently had a major influence on those artist’s who were looking to make it big. This marked the first time that music within the African American community got some national attention during the payola scandal Alan Freed “first played Rhythm & Blues (R & B, or “race music”) in 1951. Until that time, the music remained largely in the black community”. [4] Until this point the music that was primarily known in the African American communities had some exposure on some mainstream radio stations because of guys like Alan Freed, however the principle of exploiting these musicians and using the advantage of their position to gain some financial power at the expense of the lack of acceptance of African American’s can be considered a little disingenuous because of the situation even though these musicians had major talent which led into the birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll.