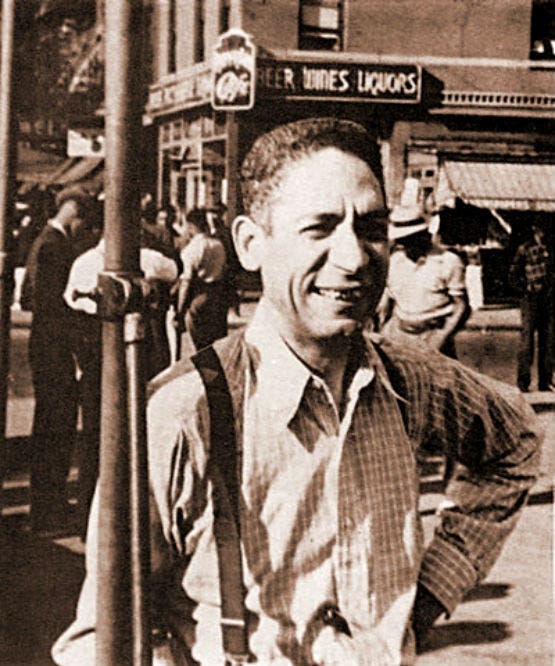

Around 100 years ago two boxers competed for the “heavyweight king of the world” in a wooden arena in Reno, Nevada. James Jackson Jeffries was referred to as the “Boilermaker”. After retiring from his undefeated career he started farming. Age 35, six foot one and a half inches, 227 pounds. John “Jack” Arthur Johnson was referred to as the “Galveston Giant”, a previous title winner. Age 32, five foot eleven inches, and lighter than Jeffries. Johnson had everything going for him, except that he was African-American. Going into the fight Jeffries stated: “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a Negro”. Johnson on the other hand had equal rights on the line and he would not back down (Walsh, 2010).

The only thing Scott Joplin had in common with Johnson is that he too was African-American. Joplin was born in 1867 in Texas on the “black side of town”. He studied piano and European musical culture and became famous in 1899 for his work “Maple Leaf Rag”. Joplin was in New York City around the time of the fight of the century completing his opera: Treem

onisha. Ragtime got a different spin put on it by Joplin; he added African syncopation and opera lyrics (Walsh, 2010).

Joplin wanted more than fame. As did Johnson.

Newspapers lit up the following day to rehash what occurred once the fight had ended. Most of the twenty six people dead and hundreds injured were black (Walsh, 2010).

Johnson went on to get married a number of times, lose more fights, and go to prison. In 1946 he crashed while racing and died at age 68 (Walsh, 2010).

Joplin couldn’t find publishers for his work, his health failed, his pia

no rags dwindled, and in 1917 he died at age 49. His work Treemonisha finally got its world depute in 1972 (Walsh, 2010).

Optimism for the African-American Community

Joplin was hopeful when President Roosevelt had Booker T. Washington at the White House for dinner in 1901. Joplin honoured this event in his work. However his optimism was not shared by othe

rs as racist newspapers spread the following day (Walsh, 2010). Joplin continued to compose music that referenced important events and ones that related to the harsh realities of African-American.

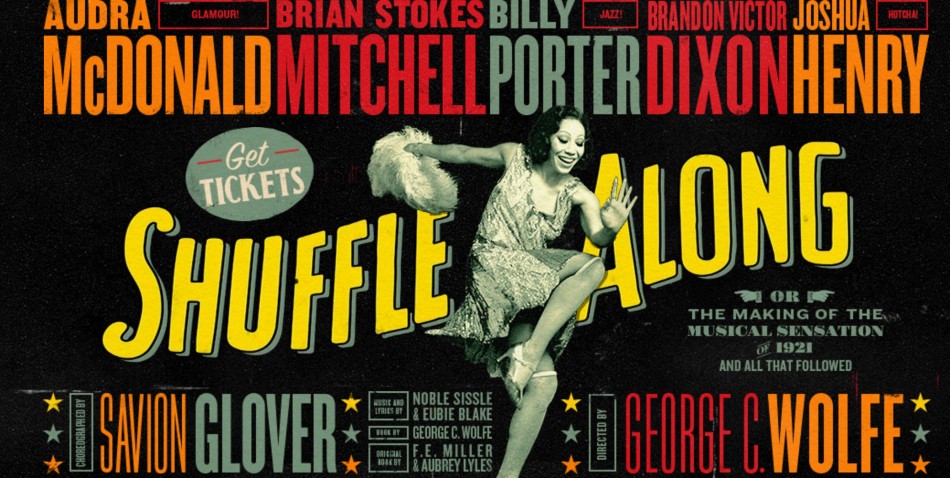

In 1910 black migrants began to learn of the opportunities that they had been kept from in the past: sports and entertainment. These outlets allowed immigrants to work towards “the American dream” (Walsh, 2010). All-black musicals on Broadway began to flourish; Clorindy, the Origin of th

e Cakewalk, and In Dahomey. The Harlem renaissance began in the 1920s encompassing poets, painters, writers, and musicians. Joplin missed it by a few years (Walsh, 2010). The dramas, shows, songs, and art culture get-togethers aimed to make the relationship between the races less violent.

Sports too, especially boxing, allowed for the mingling of races though

white America viewed the heavyweight title as a symbol of white supremacy. The fight was viewed in theatres everywhere. Jeffries couldn’t keep up to Johnson’s quick movements. In the 15th round Jeffries finally got floored and lost for the first time. Johnson reflected the growing sense of optimism in a less humbling way than Joplin did but they for the same reasons. Equal rights. Johnson’s successes encouraged other African-American athletes to compete against white people in American stadium

s to demand equality. Johnson taking down Jeffries was a huge shock to the nation, an African-American boxer won the heavyweight title again in 1937 (Walsh, 2010).

Stereotypes

Johnson used his fame with an attitude of “anything you can do I can do better”. Throughout the fight he taunted Jeffries nonstop (Walsh, 2010). Johnson challenged racial stereotypes by fighting a well-known boxer and winning, becoming famous, attaining wealth, working his

butt off, and getting with the ladies. He bought fast cars, dated and married white women, and opened cafes and nightclubs to prove his point (Walsh, 2010).

Philosophy

“In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” – Booker T. Wa

shington

Joplin intentionally adhered to the philosophy of Booker T. Washington while Johnson unintentionally embraced the philosophy. Joplin’s Treemonisha reflected Washington’s lesson because the young female character lead her people, defeated obstacles, and advocated for education. Washington believed training and education were the keys to racial advancement and that one should demonstrate equality with patience

, industry, thrift, and usefulness. Johnson embraced the philosophy through his boxing training and overcame obstacles by winning the heavyweight championship (Walsh, 2010).

Vulture Tone

The tone of the article by Mark Harris suggests that everybody feels sorry for themselves and no one takes responsibility. Comparing it

to the article by Michael Walsh it is a lot more negative. Walsh’s article was hopeful regarding the future of sport and music for African-Americans, it encompassed the attitude of “it can only get better (Walsh, 2010). In contrast, Harris’s article expresses that hope for humanity

is lost because we are a materialistic society and instead of caring about natural disasters and poverty we are tuning in to watch two men make millions of dollars by beating each other half to death (Harris, 2017).

Eras of History

Harris’s article suggests that celebrities, and as a result, people in general, are constantly re-branding themselves in the era of Trump. Pop culture embodies a man who is self-selling, ignorant and cynical (Harris, 2017). We live by the retraction of personal responsibility, we clear ourselves from blame. Pop culture wouldn’t be popular if it weren’t for us. We share the fault. This statement highlights what the forefront issues are in our society “seeking fame, not love, because, after all, when you’re a star, they let you do anything” (Harris, 2017). Wealth and power are the be-all, end-all.

Walsh’s article suggests that people were held responsible for their actions. The era, for African-Americans, embodied Washington’s philosophy where each finger had to be contribute to the hand. One should be patient and useful whereas Harris’s article suggests the opposite (Walsh, 2010).

Influence on Popular Music

Reading the article makes me think twice about listening to popular music these days. I wasn’t thinking about Taylor Swift in that light at all. I own many of her cds but I have realized that she promotes being a victim and she has branded herself promiscuously so that I can no longer take her seriously. When you turn on the radio you should try to understand what the artist is getting at and what story they are trying to tell. I’m positive my interest in songs played on C95 will dwindle now that I have the Trump era mindset in my head.

#M2Q2

Harris, M. (2017). Taylor Swift’s ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ Is the First Pure Piece of Trump-Era Pop Art. Vulture. Retrieved from http://www.vulture.com/2017/08/taylor-swift-look-what-you-made-me-do-pure-trump-era-pop-art.html

Walsh, M. (2010). A Year of Hope for Joplin and Johnson. Smithsonian. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/a-year-of-hope-for-joplin-and-johnson-123024/

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/A-309976-1437588951-1632.jpeg.jpg)