Developed by:

Colleen Anne Dell, PhD, Department of Sociology, University of Saskatchewan

Reviewers:

Maryellen Gibson, MPH, Department of Sociology, University of Saskatchewan

M. D. Daschuk, PhD, Department of Sociology, University of Saskatchewan

Therapy Dog Handler Reviewer:

Jane Smith, B.Trad., B.Ed, MStJ, St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Program

Introduction

Before we jump into the four learning modules that make up this course, there is a bit of background information you may find useful. Some of you know a lot of this already and can skim through it. Information like who is a therapy dog and where do they visit with a human handler, what is an Animal Assisted Activity, how are our visits with our dogs beneficial to the people we visit with, and what is the human-animal bond and is it a part of a therapy dog visit?

Regardless of your level of prior knowledge, there is one really important message to start off with – and that is why this course exists. For this understanding, let’s turn to St. John Ambulance therapy dog handler Jane Smith to give us a bit of background.

Figure 1-1: Jane with Murphy the Therapy Dog. Permission: Courtesy of Jane Smith, St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Program.

This course is the result of my desire to be a better therapy dog handler. Myself and my dog Murphy have been a St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Team since the Fall of 2014. I quickly learned from our very first visit that Murphy’s ability to generate feelings of comfort and support among the people we visit with can be enhanced or diminished by how well I guide the interaction. Over our many years together as a therapy dog team, we have visited a lot of different people in a lot of different places. This ranges from joyous occasions, such as at Camp Easter Seal for kids, through to deeply sad occasions, like a grieving family in a hospital.

I see myself as an “ordinary person” who simply wants to help others through my dog. I have no formal training in areas like diversity, trauma, self-care, and dog behavior. But I knew I wanted to learn more about these areas so I could avoid diminishing Murphy’s “magic” during our visits. To do this I knew I needed more knowledge.

A series of events resulted in me donating some of the proceeds of the sale of my book Murphy Mondays (which details my visits with therapy dog Murphy at the Royal University Hospital Emergency Department) to the University of Saskatchewan, Office of One Health and Wellness, to develop this course!

I am so incredibly excited about this course. I enjoyed reviewing the modules while at the same time learning from them. The course addresses everything I wanted to learn and want other handlers to know about. Dr. Dell and her team in the One Health & Wellness office and other University of Saskatchewan faculty and staff who supported us, the expert speakers, the handlers who volunteered their stories, and many others have all done an exceptional job on the course.

I am really happy to share too that you don’t need to be a therapy dog handler to benefit from the course. Any one can! If you want to learn more about inclusion and diversity, supporting people with anxiety or trauma in their background, about the importance of self-care, or about understanding your dog, this is the course for you.

ENJOY!Jane Smith

When you have finished this module, you should be able to:

- Define who therapy dogs are and who they visit.

- Identify the St. John Ambulance therapy dog program as an Animal Assisted Activity.

- Acknowledge One Health, and zooeyia specifically, as a framework to understand the benefits of therapy dog visiting.

- Describe the role of the human-animal bond, or connection, in therapy dog visiting.

- Therapy dogs

- Animal Assisted Activities

- Companion animal or pet

- One Health

- Zoonosis

- Zooeyia

- Human-Animal Bond

Essential Information for Therapy Dog Handlers

Click to expand each section.

Who are Therapy Dogs & Who Do They Visit?

If you are taking this course you likely already know who therapy dogs are, but in case you don’t, therapy dogs are commonly defined as “dogs who go with their owners to volunteer in settings such as schools, hospitals, and nursing homes” (American Kennel Club). In the One Health & Wellness office at the University of Saskatchewan we commonly refer to therapy dogs as really friendly family pets that love to visit with people and help brighten their day.

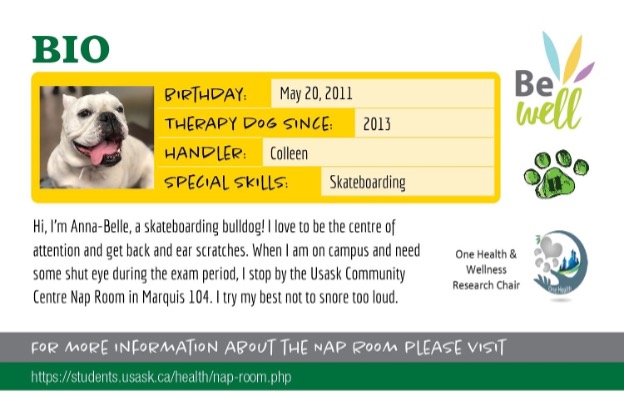

Therapy dogs can be any breed and size of dog. The president of the American Kennel Club has said that “[a]ll 200 AKC breeds can be a therapy dog depending on the temperament of the individual dog and matching the dog to the right setting” (American Kennel Club). In the One Health & Wellness office you also often hear us say that you cannot train a dog to be a therapy dog, it is just who they are. It is their personality. You can of course train a dog to be polite when out in public, and this can help them pass their therapy dog test. Therapy dog Anna-Belle, pictured here, loved to visit with people in the community, including on the University of Saskatchewan campus. It is just who she was. You can learn more about Anna-Belle in her obituary (2011-2021).

|

|

Figure 1-2: Source: Permission: Courtesy of One Health & Wellness Office.

If you are new to the therapy dog field, you can develop a greater understanding of therapy dog team visiting in these two videos. The first is an interview with St. John Ambulance therapy dog handler Jane Smith on the program You Rock about her work with therapy dog Murphy.

The second video features the work of therapy dog handler Wendi Stoeber and therapy dog Womble, and other St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Teams, visiting on the University of Saskatchewan campus in the PAWS Your Stress program.

Animal Assisted Interventions

There is some debate on the use of the term therapy dog for dogs that are volunteering their time in the community in what are commonly referred to as animal assisted activities (AAAs) (Howell, 2022). AAAs are formally defined by some as activities that “provide opportunities for motivational, educational, and/or recreational benefits to enhance [human] quality of life. [I]nformal in nature, these activities are delivered by a specially trained professional, paraprofessional, and/or volunteer, in partnership with an animal that meets specific criteria for suitability” (Pet Partners, 2022). While AAAs are not therapy per se, they can be therapeutic. This is why we use the term therapy dog in this course. Other common and emerging terms include wellness dog and comfort dog.

A variety of animals, not just dogs, can be involved in AAAs – from horses and cats through to reptiles and rabbits. With AAAs occurring in such a broad range of settings, like elementary schools and older adult residences, it is important to pay particular attention to who the participants are and what their needs are, as well as that of the handlers and therapy animals. For example, it is essential to consider diversity amongt therapy dog program participants and use inclusive language and visiting practices. Likewise, it is important to have basic mental health awareness and skills as a handler when visiting. At the same time, therapy dog handler self-care and peer support are important to recognize. So too is awareness and skills specific to therapy dog behavior and care

As shared, St. John Ambulance (2020) and other therapy dog organizations offer some information about visiting as a therapy dog team but there is a need for more. Once again, the aim of this course is to augment the information currently available with specialized therapy dog handler education. The need for this education is supported in a recent survey of therapy dog programs that identified the need for improving therapy dog visiting guidelines (Serpell, 2020). It is the handlers that put these guidelines into action. There is some excellent foundational work that can be built off of, including the 2014 International Association Human-Animal Interaction Organizations white paper on therapy dog visiting best practices, and the Therapy Dog Bill of Rights (Howie, 2015).

This 2020 survey of therapy dog programs also suggests the need for more research to be done (Serpell). This was also mentioned in the video introduction to the course by Dr. Colleen Dell, and specifically the need for high quality studies, and that more research is emerging on the effectiveness of therapy dog visiting on human health (Cole et al, 2007; Solomon 2010; Shen 2018; Carey 2021). She also mentioned that research attention is increasingly being given to the welfare of therapy dogs (Glenk and Foltin 2021; AAHA 2021). And with the COVID-19 pandemic, some therapy dog teams began visiting online and there has been research released on the effectiveness of this novel approach (Dell et al., 2021). It is an exciting time to be a therapy dog handler!

One Health and Zooeyia

Why is there all this interest in therapy dogs all of sudden? A One Health framework is gaining recognition, and it acknowledges that the health of humans, animals, and our shared environment are interconnected. According to the One Health Commission, One Health is “an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals and ecosystems. It recognizes the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and interdependent” (One Health Commission).

Watch a one minute video about how Dr. Colleen Dell draws on a One Health framework in her research with therapy dogs.

The Challenges

The majority of attention within the One Health field to date has focused on diseases that can spread from animals to humans, such as West Nile, rabies, lyme, and Salmonella. These are called zoonoses. As an example, Dr. Joe Rubin and Bev Morrison from the University of Saskatchewan assessed the presence of zoonotic bacteria that could potentially pass from dogs to humans, including Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli, with a sample of visiting St. John Ambulance therapy dogs at a Saskatoon hospital. They determined that some of the dogs carried some of the bacteria, which would be common for household pets too, but none carried the difficult to treat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) which hospitals are challenged with (Reubin et al, 2019).

Figure 1-3: Saving lives by taking a One Health approach. Source: Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

There can also be challenges associated with pets in our lives beyond zoonotic disease transmission, such as burden on financial resources, impact on the environment, and stress associated with their illness. We see this with the COVID-19 pandemic, including dogs and other pets being returned to animal shelters for various reasons (e.g., owner return to work, too costly to maintain). These challenges also need to be considered in a One Health framework.

The Benefits

Since 2011, there has been emerging attention to the PAWSitive (positive) inverse of zoonosis in a One Health framework, and that is zooeyia. Zooeyia is recognition of the health benefits of animals in humans’ lives, and specifically companion animals (Hodgson and Darling, 2011). The originators of the zooeyia term suggest that pets benefit human health in four key ways: as builders of social capital (e.g., develop networks), as agents of harm reduction (e.g., decrease tobacco exposure around pets), as motivators for healthy behavior change (e.g., regular eating schedule), and as potential participants in treatment plans” (2015:526). Can you identify how therapy dogs might be able to assist in each of these areas?

Complementary Frameworks

There are many complementary lenses through which we can consider the benefits of therapy dog visiting, each with its own important contribution. In applying a One Health framework to therapy dog visiting, it has been suggested that there is a need to consider “under which circumstances no tradeoff of human benefits against animal health and well-being ensue and under which circumstances animals could benefit from such interactions” (Glenk and Folten 2021,1). A One Welfare expands upon a One Health framework, specifically concentrating on the interconnections between animal welfare, human wellbeing, and environment conservation (Mellor et al, 2020).

Team members Chalmers and Dell (2015) have written about the application of One Health to the study of therapy dogs, noting it is “not the first attempt to account for the animal–human–environment interface. Some synergy is also found with non-Western understandings, including Indigenous worldviews”. McGinnis et al. (2019) take this observation further, outlining the destructive role of colonization on Indigenous peoples’ relationship with their more-than-human counterparts. They state that “[t]raditionally Indigenous peoples positioned animals as equitable partners in interconnected human and more-than human networks” (1).

Human-Animal Bond or Connection

The term human-animal bond was first applied in the late 1970s, when it was recognized that “healthy relationships with pets and their owners involve a complex psychological and physiological interaction that appears to have a profound influence on both human and animal health and behavior” (Fine, 2019, 6). The benefits of the human-animal bond can positively influence such things as human health (e.g., exercise, depression), social interactions, support, and therapeutic interventions (Serpell et al., 2017). Our team researcher, Dr. Holly McKenzie found that St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog handlers felt supported by their therapy dogs and other companion animals they live with during the COVID-19 pandemic during 2020 and early 2021. This support took various forms, including: prompting handlers to maintain or build new routines that include getting outside and going for walks, bringing moments of levity and joy, and providing companionship and friendship during this stressful and isolating time.

The positive benefits of visiting with therapy dogs are often understood as the result of the human-animal bond, or connection. According to the authors who coined the term (Hodgson and Darling, 2011), zooeyia “is the evidence base for the philosophical construct of the human-animal bond”. The human-animal bond is defined as “a mutually beneficial and dynamic relationship between people and animals that is influenced by behaviors essential to the health and wellbeing of both. This includes, among other things, emotional, psychological, and physical interactions of people, animals, and the environment” (American Veterinary Medical Association). Key here is that the beneficial relationship between humans and animals is mutual.

There has been increasing attention to the benefits of the human-animal bond, or connection, with visiting therapy dogs. For example, the work of Horowitz (2011) summarizes supportive research findings in a variety of health care settings. More specific, members of our team identified the human-animal bond between prisoners and therapy dogs as an important relational connection that benefited their mental health (Dell 2019). Other team members even found this to be the case for prisoners who visited with St. John Ambulance therapy dogs virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic (Scheck et al, 2022).

The human-animal bond has been increasingly recognized in modern times, but there is emerging evidence that it was present historically. This was mainly with canines who have the longest history of domestication. The work of Dr. Robert Losey, an anthropologist at the University of Alberta, has documented this. Watch this 3-minute video – The Ancient Relationship Between Human and Dog – to learn more. Or, watch a full length 60-minute webinar Dr. Losey recorded for our team.

Figure 1-4: Poster advertising webinar “A Deep History of the Human-Dog Bond.” Permission: Courtesy of One Health & Wellness Office.

Looking Forward

In this module, you were provided with an overview of the course. You were introduced to how this course came to be and the four key topics to be covered. You were introduced to One Health, and zooeyia, as a paws-ible (possible) framework in which to understand the benefits of therapy dog visiting. Alongside this, the role of the human-animal bond, or connection, in therapy dog visiting was shared. The St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Program was also described as an Animal Assisted Activity. Hopefully you are excited at this point to move onto the remainder of the course!

Each module is set up to introduce you to an expert speaker in the four areas to increase your awareness and skills. The first two speakers, Nancy Poole and Erin Beckwell, will speak to the participant experience in the therapy dog visit; Nancy will address the need for handlers to consider participant diversity and inclusion and Erin will discuss participant mental health needs that handlers should be aware of. Janelle Jakiw will then switch gears in module four and examine therapy dog handler self-care and peer support. And finally, Anne Howie will address understanding therapy dog behavior and care in module five.

In each of their presentations, the speaker cover:

- What handlers need to know about the topic area and/or misperceptions they may have about it;

- How these misperceptions are likely to impact their work as a therapy dog handler, and

- What strategies or solutions therapy dog handlers should consider during their visits with community members.

Before each video presentation, a therapy dog handler, alongside their therapy dog, will share an experience or two that they had in the four topic areas. They will highlight what they wish they would have had more understanding about at the time. These honest stories are shared with the hope that they can help course participants in real-life scenarios and highlight the importance of ongoing therapy dog handler education.

Glossary

Animal Assisted Activities: “Animal-assisted activities provide opportunities for motivational, educational, and/or recreational benefits to enhance quality of life. While more informal in nature, these activities are delivered by a specially trained professional, paraprofessional, and/or volunteer, in partnership with an animal that meets specific criteria for suitability” (Pet Partners, 2022).

Companion animal or pet: “[C]ompanion animals should be domesticated or domestic-bred animals whose physical, emotional, behavioral and social needs can be readily met as companions in the home, or in close daily relationship with humans” (American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). The term companion animal is preferred by some over pet because it indicates a mutual interaction rather than ownership.

Human-Animal Bond: “The human-animal bond is a mutually beneficial and dynamic relationship between people and animals that is influenced by behaviors essential to the health and wellbeing of both. This includes, among other things, emotional, psychological, and physical interactions of people, animals, and the environment” (American Veterinary Medical Association).

One Health: “One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimise the health of people, animals and ecosystems. It recognizes the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and interdependent” (One Health Commission).

Therapy Dogs: “Therapy dogs are dogs who go with their owners to volunteer in settings such as schools, hospitals, and nursing homes” (American Kennel Club).

Zooeyia: “The positive benefits to human health from interacting with animals, focussing on the companion animal” (Hodgson and Darling, 2011).

Zoonosis: “A zoonosis is an infectious disease that has jumped from a non-human animal to humans. Zoonotic pathogens may be bacterial, viral or parasitic, or may involve unconventional agents and can spread to humans through direct contact or through food, water or the environment. They represent a major public health problem around the world due to our close relationship with animals in agriculture, as companions and in the natural environment” (World Health Organization).

References

American Animal Hospital Association. 2021. “2021 AAHA Working Assistance, and Therapy Dog Guidelines”. AAHA Online <https://www.aaha.org/globalassets/02-guidelines/working-assistance-and-therapy-dog/resourcepdfs/2021-aaha-working-assistance-and-therapy-dog-guidelines.pdf>

American Kennel Club. 2022. “What Is A Therapy Dog?”. American Kennel Club Website, <https://www.akc.org/sports/title-recognition-program/therapy-dog-program/what-is-a-therapy-dog/>

American Veterinary Medical Association. 2022. “Human-Animal Bond”. AVMA Website, <https://www.avma.org/one-health/human-animal-bond#:~:text=The%20human%2Danimal%20bond%20is,%2C%20animals%2C%20and%20the%20environment>

American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty Against Animals (ASPCA). 2022. “Definition of Companion Animal” ASPCA Online, <https://www.aspca.org/about-us/aspca-policy-and-position-statements/definition-companion-animal>

Carey B, Dell CA, Stempien J, Tupper S, Rohr B, Carr E, et al. (2022) Outcomes of a controlled trial with visiting therapy dog teams on pain in adults in an emergency department. PLoS ONE 17(3): e0262599. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262599

Chalmers, A. and C. Dell. 2015. “Applying One Health to the Study of Animal-Assisted Interventions”. Ecohealth 12 (4) doi: 10.1007/s10393-015-1042-3

Cole, K., A. Gawlinski, N. Steels, J. Kotlerman. 2007. “Animal-Asisted Therapy in Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure”. American Journal of Critical Care. 16(6): 575-585. https://aacnjournals.org/ajcconline/article-abstract/16/6/575/622/Animal-Assisted-Therapy-in-Patients-Hospitalized?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Dell, C. L. Williamson., H. Mackenzie, B. Carey, M. Cruz, M. Gibson and A. Pavelich. 2021. “A Commentary about Lessons Learned: Transitioning a Therapy Dog Program Online during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Animals 11(3); 914 https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030914

Dell, C., D. Chalmers, D. Cole, J. Dixon. 2019. “Accessing Relational Connections in Prison: An Evaluation of the St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Program at Stony Mountain Institution”. The Annual Review of Interdisciplinary Justice Research. 8: 13-68. https://www.cijs.ca/_files/ugd/3ac972_064de47f9cc54950bad9c7be4d6bc155.pdf

Fine, A. 2019. “The Human Animal Bond over the Lifespan: A primer for Mental Health Professionals”. In L. Kogan and C. Blazina (Eds.). A Clinician’s Guide to Treating Companion Animal Issues. London: Academic Press, (pp. 2-19).

Glenk, L. M. and S Foltin. 2021. “Therapy Dog Welfare Revisited: A Review of the Literature”. Veterinary Sciences, 8(10):226 doi: 10.3390/vetsci8100226

Hodgson, K. and M. Darling. 2011. “Zooeyia: An essential Component of ‘One Health’. Canadian Veterinary Journal, 52 (2) 189-191. <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3022463/>

Hodgson, K., Barton, L., Darling, M., Antao, V., Kim, F., Monavvari, A. 2015. “Pets’ Impact on Your Patients’ Health: Leveraging Benefits and Mitigating Risk”. JABFM, 28 (4):526-534.

Horowitz, S. 2011. “Animal-Assisted Therapy for Inpatients: Tapping the Unique Healing Power of the Human-Animal Bond”. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 16 (6) https://doi.org/10.1089/act.2010.16603

Howell TJ, Nieforth L, Thomas-Pino C, et al. 2022. “Defining Terms Used for Animals Working in Support Roles for People with Support Needs”. Animals. (15):1975. DOI: 10.3390/ani12151975. PMID: 35953965; PMCID: PMC9367407.

Howie A. 2015. Teaming With Your Therapy Dog. West Lafayette, Purdue University Press.

International Association of Human-Animal Interaction Organizations. 2018. “The IAHAIO White Paper”. IAHAIO Website, <[1] https://iahaio.org/best-practice/white-paper-on-animal-assisted-interventions/>

McGinnis, A., A. Tesarek Kincaid, M. J. Barrett and C. Ham. 2019. “Strengthening Animal-Human Relationships as a Doorway to Indigenous Holistic Wellness. Ecopsychology, 11 (3) 162 – 173 doi: 10.1089/eco.2019.0003

One Health Commission. 2022. “What Is One Health?”. One Health Commission Website, <[1] https://www.onehealthcommission.org/en/why_one_health/what_is_one_health/>

Pet Partners. 2022. “Terminology”. Pet Partners Website, <https://petpartners.org/learn/terminology/>

Reubin, J. and B. Morrison (2019). Conference of the Canadian Association of Clinical Microbiologists and Infectious Diseases.

Scheck, H., Williamson, L., Dell, C. 2022. “Understanding Psychiatric Patients’ Experience of Virtual Animal-assisted Therapy Sessions during the COVID-19 Pandemic”. People and Animals: The International Journal of Research and Practice. 5 (1), Article 6. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/paij/vol5/iss1/6

Serpell, J. K. Kruger, L. Freeman, J Griffin and Z Y. Ng. 2020. “Current Standards and Practices Within the Therapy Dog Industry: Results of a Representative Survey of United States Therapy Dog Organizations”. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00035

Serpell,J., S. McCune, N. Gee and J. Griffith. 2017. “Current challenges to research on animal-assisted interventions. Applied Developmental Science, 21 (3) 1-11 DOI:10.1080/10888691.2016.1262775

Shaw Community Link. 2019. “You Rock: Jane Smith and Murphy”. Youtube.com, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkTq-86cxY8>

Solomon, O. 2010. “What a Dog Can Do: Children with Autism and Therapy Dogs in Social Interaction”. Journal of the Society for Psychological Anthropology. 38(1), 143-166. https://www.uclahealth.org/pac/Workfiles/PAC/ChildrenW.AutismAndTherapyDogs_Solomon.pdf

Shen, R., P. Xiong, U. Chou and B. Hall. 2018. “’We need them as much as they need us’: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence for possible mechanisms of effectiveness of animal-assisted intervention (AAI)”. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 41: 203-207 doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.10.001

St John Ambulance. 2020. “St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Program Evaluation Guidelines”. Eastern Health Online <[1] https://ltc.easternhealth.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2020/04/TD-Self-Evaluation.pdf>

University of Alberta. N.d. “The ancient relationship between human and dog”. Youtube.com, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s2z6eCCNtOk>

University of Saskatchewan, 2019. “PAWS Your Stress”. Youtube.com, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BlDP5FkuudY>

Vimeo. Nd. “One Health: Colleen Dell”. Vimeo <https://vimeo.com/179386330/1ee0934324>

World Health Organization. 2020. “Zoonoses”. WHO Website, <https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/zoonoses>