Developed by:

M. D. Daschuk, PhD, Department of Sociology; University of Saskatchewan

Colleen A. Dell, PhD, Department of Sociology; University of Saskatchewan

Nancy Poole, PhD, BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health

Reviewers:

Maryellen Gibson, MPH, Department of Sociology; University of Saskatchewan

Aliya Khalid, MA, Interdisciplinary Program; University of Saskatchewan

Therapy Dog Handler Reviewer:

Jane Smith, B.Trad., B.Ed, MStJ, St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Program

Introduction

In this module you will have the opportunity to increase your skills in and become more aware of how to interact with therapy dog program participants in ways that are respectful of their diversity and provide them with an inclusive therapy dog experience. You will learn about how the variety of negative stereotypes and stigmatization can impact participants and how therapy dog handler assumptions specifically can impact participants' experiences of a beneficial therapy dog visit. We will also touch on how learning from our mis-steps when interacting with diverse individuals can help us broaden our awareness and interaction skills. The second half of the module focuses on strategies to ensure our visits with therapy dog program participants are based in principles of awareness, safety, humility, competence, and sensitivity/responsiveness. We will focus on examples for providing gender-informed and culturally safe interactions, and suggest strategies you can apply to help participants feel safe and empowered during your therapy dog visits.

Figure 2-1: Nancy Poole and Anna-Belle the Therapy Dog. Permission: Courtesy of Colleen Dell, Department of Sociology, University of Saskatchewan.

EXPERT SPEAKER: About Dr. Nancy Poole

Nancy lives and works in BC, the traditional territory of the Lekwungen peoples. She is the Director of the Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, a virtual research and knowledge exchange centre, where she collaborates with researchers, service providers, policy makers and community-based advocates across Canada and internationally. The Centre aims to “close the loop” between research and practice to bring about social change and health improvement for women. Nancy has co-edited 5 books with Dr. Lorraine Greaves, the most recent being Gender Unchained: Notes from the Equity Frontier.

Fun Fact: In the 80s, Nancy held the position of manager and sound engineer for a lesbian rock band.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to:

- Discuss the negative impact stereotypes and stigmatization as a process can have on therapy dog program participants.

- Explain what it means to provide participants with therapy dog visits based in awareness, safety, humility, competence, and sensitivity/responsiveness.

- Describe how we can improve our responses to two aspects of diversity – gender and culture.

- Identify strategies for engaging with program participants with safety and trustworthiness, choice and collaboration, and strength.

- Stereotypes

- Stigmatization

- Awareness

- Sensitivity

- Safety (Responsiveness)

- Humility

- Competence

- Colonization

- Decolonization

- Reconciliation

Essential Information for Therapy Dog Handlers

Click to expand each section.

Introduction

Being a therapy dog handler requires giving attention to the welfare of your canine PAWtner (partner) as well as to program participants during your visit. Your therapy dog will no doubt be the centre of attention in almost all of your interactions, and rightfully so! Dogs seem to be gifted in providing people with unconditional and non-judgmental comfort and support, and offering people exactly what they seem to need at the time. There are, however, important ways that you as a therapy dog handler can help ensure the people you meet during your visits will have the best possible therapy dog visit. You and your dog will interact with people with many different experiences and needs based on their personal characteristics, such as their sex, gender identity, ethnicity or cultural background, sexual orientation, social class, ability, religious or spiritual background, age, nationality, and more! Your ability to positively contribute to a participant’s therapy dog visiting experience will depend on how well you can connect with them and help them feel comfortable during the visit.

The first section of this module highlights the importance for handlers to avoid making assumptions about the people they are visiting with based on stereotypes, and in place trying to “consider the participants’ experiences” to inform your interactions. Considering others’ experiences should be based on knowledge as well as empathy and compassion, and as a therapy dog handler, we know you have a ton of these important personal qualities!

The Significance of Standpoint and Stereotypes

Suggesting that therapy dog handlers consider the experiences of the people they visit with does not mean a handler should – or could – ever experience what it is like to be from social groups other than their own. Considering the standpoint of another individual means being aware of how characteristics like our sex, gender, ethnicity, and social class can influence our life experiences. As a society, we are (thankfully) becoming more aware of how intolerant attitudes contribute to discriminatory treatment, and how racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia (just to name a few) can negatively influence a persons’ life experiences and opportunities. Not familiar with all of these terms? No worries, there are more definitions to come later in the module.

Participants you encounter in the therapy dog program may have direct experiences with intolerant attitudes and discriminatory behavior because of negative stereotypes. Stereotypes are widely recognized assumptions that are commonly made about people based on the groups they belong to. For example, stereotypes can be based around a person’s sex, ethnicity, or sexual orientation, as well as other characteristics like someone’s occupation, personal accomplishments, or level of education. While stereotypes can be positive – such as the stereotype of the kind, caring, and talented St. John Ambulance therapy dog handler – they can also be negative.

Negative stereotypes oftentimes lead to stigmatization. Stigmatization is a process where more powerful social groups use stereotypes about less powerful groups to discredit their humanity and blame them for the discriminatory treatment they experience (Fudge Schormans, 2014). For example, racial stereotypes characterizing non-European cultures as less intelligent and uncivilized were created to justify colonization and slavery and, to this day, remain in use to ‘explain’ the over-representation of Indigenous and Black populations in prison. There are common stereotypes today centered around individuals who do not conform with dominant (albeit unfair) norms and expectations in society, such as people who identify as transgender, people diagnosed with a substance use disorder, or people that do not have permanent employment or housing. Stigmatization can also be internalized by individuals and occur within a stigmatized group (Major and O’Brien, 2005).

As another example to think through stigmatization, stereotypes can lead to discriminatory treatment against some dogs. There are stereotypes suggesting that certain breeds of dogs are naturally prone to aggression, are unpredictable, and pose a risk to children. These stereotypes have inspired movements to outlaw the ownership of Pitbull, Doberman and Rottweiler dogs – even though there is an absence of evidence that these breeds pose a greater danger compared to any other dog breed. Remember from the introductory module that any breed and size of dog can be a potential therapy dog!

This three-step activity is a bit unique compared to the others you will come across in the course. It involves reflecting on some of your own experiences and using them to consider the experiences of another person who is being treated poorly based on stereotypes.

Use the following Self-Reflection Tool to complete this activity.

Harms

Negative stereotypes can cause people harm, including to their physical and mental health. Research evidence shows us that stigmatization contributes to some people being provided inferior healthcare services (Drabish and Theek, 2022, Kennedy et. al., 2017), others experiencing higher incidents of disease (Government of Canada, 2019; Stangl et. al., 2019), and can impede people who are fearful of being treated poorly to access health care when in need (Whitehead et. al., 2016, Merino et. al., 2018). Consider a recent review of the treatment of Indigenous peoples in British Columbia’s health care system; it concluded there is widespread systemic racism and discrimination (Provincial Government of BC, 2021). The report shares that “[t]his racism results in a range of negative impacts, harms, and even death”. (6). Consider another troubling example, a 2022 statement from the Mental Health Commission of Canada that shares: “People with lived experiences of mental health and addiction problems often report feeling devalued, dismissed and dehumanized by many of the healthcare professionals with whom they come into contact”. Negative stereotypes and stigmatization are an unfortunate reality in our society and can have disastrous consequences.

Given that the very purpose of a therapy dog program is to help participants feel valued, heard, and experience a connection with your dog, exposing them to biased treatment based in stereotypical assumptions is the very last thing we want to do. To prevent this from happening, we need to make sure as handlers we are as aware and educated as possible.

One unfortunate reality about making assumptions, is that we all do it on a daily basis. When we encounter people or groups we are not familiar with, the human mind automatically thinks about all the information we have collected throughout our lives – including stereotypes – to guide how we should act. As a really simple illustration, let’s say that you were bitten by a standard poodle breed dog when you were a young child, and if you were not educated about what happened in that scenario, to this day as an adult you may stereotype all poodles as vicious dogs and be fearful of them all.

As a therapy dog handler, it is important to be aware of the harms stereotypes can cause and be mindful of how our own assumptions can negatively influence our interaction with someone. This is where considering the standpoint of the people we visit with is important, and this includes discriminatory treatment they have encountered in their lives. That said, you should not be too hard on yourself when making oversights or mistakes – just as using assumptions to guide our conduct is innately human, so too is learning from our mis-steps and allowing them to inform our behavior moving forward. As the following story from St. John therapy dog handler Jane Smith shows us, reflecting on and learning from incorrect assumptions you make about therapy dog program participants can allow for greater personal awareness and improve relationships with those you will be visiting in the future!

Handler Story (Murphy and Jane Smith)

Please watch the following video.

Written content and video by Jane Smith

Who are you?

My name is Jane Smith and I’m a St. John Ambulance therapy dog handler. I’m retired from teaching and moved to Saskatoon from Halifax, Nova Scotia in 2014.

Who is your therapy dog?

This is Murphy. He is a 10 year- old English Springer Spaniel, and I say without the “spring” because springers are typically very hyper. Murphy has been very calm since we got him at 7 months of age. This makes him a great therapy dog. We have been a St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Team since 2014. Murphy loves his food and treats. Although this very quiet and calm dog will howl when it is his mealtime. Murphy really enjoys going for walks. A very definite favorite thing to do for him is snuggling with people he visits.

What are you going to share?

This story is about Murphy and my first placement as a St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Team in The Irene & Leslie Dubé Centre for Mental Health. We have visited there weekly for over 5 years. I have three stories for us to reflect on from the visits there.

One day Murphy and I walked into the adolescent unit of the mental health centre and doctors, nurses, and various staff were hurrying about around one young person. I asked if Murphy and I could help and they eagerly said yes. Murphy sat on a chair beside this individual and snuggled his head on their lap while the person petted him. This young person was in crisis and everyone was trying to support them. The young person looked like a girl to me, so I said “she”. The care team responded immediately. I am not sure what was said anymore but it became abundantly clear this young person may have looked like a girl to me but was identifying as a boy. I apologized and fortunately the care team helped to make sure there was minimum negative impact from my words. Also fortunately, after petting Murphy on their lap for about an hour, they were stable enough for us to leave. Murphy had his usual calming effect despite my language that was stigmatizing for this young person.

We visited a young adult weekly for years on the adult side of The Dubé Mental Health Centre. This individual had both mental health issues and cognitive challenges. He also had been violent in his past. I am quite certain that he loved Murphy and Murphy loved him. He would get so excited when he saw Murphy, talking fast and loud and sometimes jumping up and down. The nurses would often gather around their station to watch when we walked onto the unit to witness his joy and excitement. This young adult started calling me “Auntie” after a few visits, which I paid little attention to. I just thought his cognitive challenges were leading him to call me “Auntie”. We followed him to a group home for visits with Murphy and staff there were also excited when we arrived. In both the Dubé Centre and the group home, this individual’s behavior would be much calmer after a visit with Murphy. It was not until after I took a course in cultural humility that I realized the possibly he thought of me as family. I missed out on an even deeper relationship with him because I didn’t understand the Indigenous perspective on family. Murphy worked his magic but I could have increased that magic.

Another individual Murphy and I visited with weekly for years in The Dubé Mental Health Centre looked to me like he was homeless and hardly ever spoke to me. He too had been violent in his past. Murphy seemed to love to visit with this man. Murphy would seek him out when we arrived onto the unit and climb onto his chair and snuggle. I was not that impressed with the man. I didn’t pay any more attention than necessary to him. I didn’t think we were making that much of a difference. But I was wrong. The saying “Never judge a book by it’s cover” sure applied here. The nurses and doctor asked me to follow to do visits at a secure care home when they found a placement for him there. They told me that he normally swore at them but when Murphy had visited the man was much kinder. So, we did follow him to his new residence and he began to talk to me. I learned all about his family. Once I opened my heart just like Murphy, my heart filled with empathy. The nurses would often tell me of concerns with his behavior and Murphy and I continued to inspire calmer behavior. He would often hold onto the second leash on Murphy and walk around and outside the care home and introduce Murphy to people. I remember this man started out sharing very little with me. But as I opened myself, we started to develop a relationship. In fact, this individual and I wrote an article together about his relationship with Murphy and it was published in the book Sharing The Love. When he arrived in the emergency room one day at our local hospital, Murphy and I just happened to be there. Murphy snuggled him and rode on his bed beside him as they transported him to a ward. I made sure all the nurses and doctors knew how much this man meant to me. He died shortly thereafter and Murphy and I spoke at his funeral. Murphy whined and I read our article.

What do you wish you knew at the time?

Looking back, I wish I knew to be careful with the pronouns I used, especially in the mental health centre. I wish I knew what pronouns to use and what pitfalls to avoid. I wish I had better understood Indigenous culture so I could deepen Murphy’s magic. Knowing more about cultures other than my own would improve my facilitation of Murphy’s calming presence. Acknowledging I sometimes might have a socioeconomic bias or blinkers on would also have helped ensure I quickly developed a relationship that brought out the best in Murphy and in the person we visited. I need to pause and listen more. And I am.

Challenging Stereotypes with Compassion and Respect

Murphy and Jane’s recollections do not only demonstrate how a handler can broaden their horizons by humbly reflecting on their mis-steps, but also that the people we visit with and who have a great deal of experience with being stereotyped can experience profound benefits when treated with compassion and respect. As you heard, Jane and therapy dog Murphy had a profound positive impact on individual’s lives. Likewise, Anna-Belle the therapy dog and team member Colleen Dell witnessed this first-hand when they pilot-tested how therapy dog visits could assist clients in an Opioid Assisted Recovery Program. Anna-Belle developed a particularly strong bond with a therapy dog program participant identified as ‘Cora’ (not her real name). This article was written about their visits together, and according to Anna-Belle (as interpreted through Colleen):

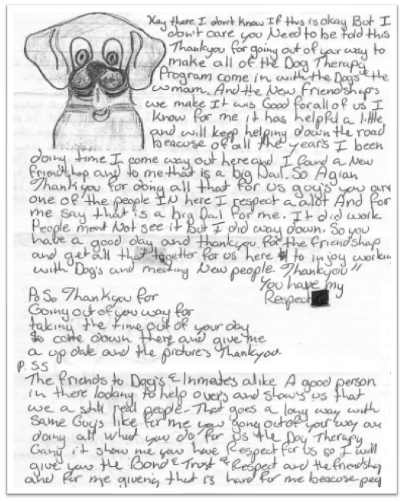

Anna-Belle and Colleen found that treating Cora with compassion and respect helped her in her recovery program, and that allowing Cora safe and sensitive interactions free of judgment motivated her to continue her recovery after her program was complete. Anna-Belle and Colleen, and other therapy dog teams, also visited maximum-security prisoners with similar results; they witnessed that treating prisoners as human beings deserving of compassion and providing non-judgmental interactions with therapy dog teams had profound positive effects. This is demonstrated in a letter that Anna-Belle and Colleen received from one of the therapy dog program participants:

Figure 2-2:Source: Dell, C.A., Chalmers, D., & Goodfellow, H. (2019). Animal Memories, page 19. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan.

Recognizing Diversity: Strategies for Meaningful Interactions

If we do our best to avoid letting assumptions based in stereotypes influence our interactions with therapy dog program participants, this can be a significant step toward allowing them to make meaningful connections with our dogs. There are additional considerations handlers visiting with diverse populations alongside their therapy dogs can keep in mind to assist with this, and include practicing awareness, sensitivity, safety (or responsiveness), humility, and competence.

Awareness is related to how much knowledge you have about the beliefs, experiences, and needs of the individuals you are visiting with. Consider, for example, that you and your therapy dog are visiting an organization that provides shelter to a recently arrived refugee population displaced by war. Ways you could improve your awareness include learning about where the individuals are from, the specific conflict they have been displaced by, and the cultural role of dogs in their home country.

Sensitivity is related to how well your interactions reflect an understanding and appreciation of the beliefs, values, and needs of a distinct population. Taking our example above further, given that you will likely be interacting with individuals who have recently experienced significant trauma (warfare and displacement), you could ensure sensitivity by holding back questions about the conflict that displaced them, such as what they witnessed and how they escaped. You may also choose not to ask questions about pets they may have had, in case they had to leave them behind.

Safety (or responsiveness) is related to how well your interactions align with the beliefs and practices that are significant to the group you are visiting with. Using the same example, if you observe that the shelter has a space dedicated for Salah (the five daily prayers of Islamic religious practice) it would coincide with safety and responsiveness to ensure your therapy dog stays away from this area. According to Islamic faith, dogs are forbidden from being in areas dedicated to religious practice and disrespecting this principle would severely undermine the effectiveness of your visit.

Humility is related to how well your interactions with therapy dog program participants reflect your awareness that your knowledge can always expand and your willingness to let individuals educate you. It would be consistent with humility to admit that you do not know a lot about Islamic perspectives on dogs and religious practices, and request to be enlightened. Empowering therapy dog program participants to take the role of educator can benefit their therapy dog experience, as well as improve your awareness about groups you may be less familiar with.

Finally, competence is related to how effective your interactions will be given the specific beliefs, values, and needs of the individuals you are visiting with. Given common Islamic religious perspectives that Muslims should not interact with dogs prior to and during religious engagements, it may be a good idea to ensure you and your therapy dog avoid visiting the organization during the times associated with Salah.

Program Participant Perspectives (Speaker – Nancy Poole)

The following presentation by Nancy Poole touches on ways to be mindful of diversity and interact with therapy dog program participants based on the principles of awareness, sensitivity, humility, competence, and safety or responsiveness. Nancy discusses strategies to help us make sure that our therapy dog visits are gender informed and culturally safe. Nancy elaborates on how perspectives on gender are evolving, including terms, and how to communicate with individuals in gender sensitive ways. She also discusses cultural safety, focusing on the importance of cultural awareness for Indigenous populations and how providing culturally sensitive interactions coincides with efforts at reconciliation and decolonization (check out the glossary for this module if you need a refresher on the meaning of some of these terms). Nancy’s presentation concludes with an activity to get you thinking about how you may want to interact with therapy dog program participants in ways that recognize and respect diversity.

In this first video, Nancy reviews some considerations that should be kept in mind as we reflect on the diversity of our therapy dog program participants. Please be aware that there are some infrequent issues with the video’s audio – our team has learned that, while dogs make fantastic therapy program partners, they are not great at media production. Our apologies!

Being Gender Inclusive

In the next video, Nancy discusses how these considerations related to diversity are relevant to providing gender-informed interactions with therapy dog program participants.

Nancy’s overview of terms commonly used to discuss gender and gender identity may be a touch intimidating if you are being introduced to these words for the first time. The following list of terms (Source: Women and Gender Equality Canada, 2022) will hopefully assist you to become more familiar with forms of gender identity, as well as assist you with the activity that follows. It is important to keep in mind too that some individuals prefer terms different than those provided here, but this chart should give you a good start on expanding your awareness of gender sensitive language!

- Gender Identity: Internal and deeply felt sense of being a man or woman, both, or neither. A person’s gender identity may or may not align with the gender typically associated with their sex. It may change over the course of someone’s lifetime.

- Gender Expression: The various ways in which people choose to express their gender identity. For example: clothes, voice, hair, make-up, etc. A person’s gender expression may not align with societal expectations of gender. It is therefore not a reliable indicator of a person’s gender identity.

- Non-Binary: Referring to a person whose gender identity does not align with a binary understanding of gender such as man or woman. It is a gender identity which may include man and woman, androgynous, fluid, multiple, no gender, or a different gender outside of the “woman—man” spectrum (e.g., Genderqueer).

- Gender Fluid: A person whose gender identity varies over time and may include male, female, and non-binary gender identities.

- LGBTQ2: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Two-Spirit. This is the acronym used by the Government of Canada to refer to the Canadian community.

- Transgender: A person whose gender identity differs from what is typically associated with the sex they were assigned at birth.

- Two-Spirit: An English term used to broadly capture concepts traditional to many Indigenous cultures. It is a culturally-specific identity used by some Indigenous people to indicate a person whose gender identity, spiritual identity, and/or sexual orientation comprises both male and female spirits.

- Cisgender: A person who identifies with the gender they were assigned at birth.

- Questioning: A person who is uncertain about their sexual orientation and/or gender identity; this can be a transitory or a lasting identity.

For this activity, you are provided with three scenarios involving a therapy dog handler who could be interacting with program participants in a more gender-informed way. Based on the information provided, please identify ways that the handler in the example is not being gender sensitive and explain how their conduct could improve to be better gender-informed. After taking some time to think about the situation, examine the suggested responses.

Promoting Cultural Safety

In the next video Nancy discusses the importance of considering the cultural backgrounds of the individuals that you and your therapy dog are visiting. Here, Nancy pays particular attention to the concepts of cultural humility and cultural safety.

Nancy’s discussion about the importance of providing culturally safe therapy dog visits is of particular significance when interacting with Indigenous populations, including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples. This is due to the horrific legacy that colonialism has had upon Indigenous cultures throughout North America and elsewhere across the globe, and the continuing negative impact of colonization upon Indigenous peoples’ health and welfare (as was introduced above in discussing stereotypes and stigmatization).

Colonialism is understood as one group of people taking control over another. Consider that “[b]y 1914, a large majority of the world’s nations had been colonized by Europeans at some point” (Blakemore, 2019). In Canada, key colonizing acts include the passage of the Indian Act and the residential school system, which were designed to force Indigenous populations to assimilate into the dominant settler culture. For example, the Indian Act prohibited Indigenous communities from participating in traditional cultural practices and forbid their involvement with political organization (Joseph, 2016), and Indigenous students in residential schools were physically abused for using their traditional languages (Judd, 2021). The attempted destruction of Indigenous peoples’ culture, values, language, and traditions is a horrendous part of Canada’s history.

The release of findings from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission investigation into Canada’s residential school system have led to overwhelming demands that Canada provide opportunities for decolonization and reconciliation with Indigenous populations. Let’s define these two terms:

- Decolonization “requires non-Indigenous Canadians to recognize and accept the reality of Canada’s colonial history, accept how that history paralyzed Indigenous Peoples, and how it continues to subjugate Indigenous Peoples. Decolonization requires non-Indigenous individuals, governments, institutions and organizations to create the space and support for Indigenous Peoples to reclaim all that was taken from them.” (Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., 2022).

- Reconciliation refers to a process through which Indigenous populations and Canadians “[engage] in dialogue that revitalizes the relationships between Indigenous people and all Canadians in order to build vibrant, resilient and sustainable communities” (Reconciliation Canada, 2022).

Both decolonization and reconciliation centre around empowering Indigenous peoples to revitalize the traditions and ways of understanding the world that colonialism sought to extinguish, and form relationships with Canada that are based around equality and mutual respect. One crucial element of both decolonization and reconciliation is greater public awareness and education. The emergence of the Every Child Matters movement and declaration of September 30th as Orange Shirt Day in Canada is one example of the intention to draw greater public awareness to the violence inflicted on Indigenous residential school students. For more information, you can visit the Every Child Matters Educational Package. Given Nancy’s presentation, it would be fair to say that providing interactions based in cultural humility and ensuring cultural safety coincide closely with the goals of decolonization and reconciliation.

Here, we provide a reflection on an Indigenous way of knowing the world, and specific to the significant role animals play in life, as prepared by traditional Indigenous knowledge advocate Larry J. Laliberte. (Click to move through the 4 pages of the PDF.)

Traditional Indigenous Knowledge - Animism

Source: Permission: Courtesy of Larry J. Laliberte, Traditional Indigenous Knowledge Advocate, as prepared for the One Health & Wellness Office.

Common Approaches & Strategies

Nancy’s final video discusses strategies you can use to help ensure your interactions with therapy dog program participants are gender-informed and align with cultural humility and safety.

Earlier, this module discussed the importance for handlers to try not to make assumptions about therapy dog program participants and provide them with non-judgmental interactions. Nancy shared in her video that therapy dog handlers can actively help individuals have meaningful experiences by providing comfort and empowerment during our interactions. To this end, let’s revisit the activity Nancy recommends to help you reflect on how you can interact with individuals in ways that are based in safety and trustworthiness, allow for choice and collaboration, and provide therapy dog program participants an opportunity to recognize their strengths.

Use the following Self-Reflection Tool to complete this activity.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

As a therapy dog handler, one of your more significant responsibilities will be to help provide program participants with the opportunity to make a meaningful connection with your therapy dog (and you too). This module opened by suggesting that a necessary first step is to recognize the negative treatment and dehumanizing experiences individuals may have faced due to stereotypes and stigmatization. The best way to ensure people feel safe in their therapy dog interactions with you is to do your best to avoid making assumptions or letting any judgements you may hold influence your interactions. For example, be sure to pay attention to the ways you speak with or refer to individuals, and use anti-stigmatizing language whenever possible. As therapy dog handler Jane’s recollections show, it is likely you will make some mistakes as you engage with diverse populations, and if you learn from these mis-steps it can help you make more meaningful connections and have a profound positive influence in the lives of others in the future.

Next, Nancy’s presentation identified how therapy dog handlers can base their visits around the principles of awareness, sensitivity, humility, competence, and safety (or responsiveness). This module also shared how handlers can be gender informed in part through their awareness of contemporary gender terminology. Finally, we discussed how practices based in cultural humility and cultural safety align with important movements toward reconciliation and decolonization for Indigenous populations.

Nancy’s notes on engaging with individuals in ways that provide safety and opportunities for empowerment bring us back to a significant point: the goal of the therapy dog program ultimately rests with your ability to provide people who may feel powerless and devalued opportunities to feel empowerment and validation. Providing conditions that best allow individuals an opportunity for meaningful engagement is a central goal for therapy dog handlers. Our next module shifts our focus to the equal importance of handlers providing trauma-informed therapy dog visits.

Discussion/Self-Reflection Questions

- Are you able to identify that diversity has many intersecting aspects and the implications of this for therapy dog handlers?

- Are you able to describe how we can improve our responses to two aspects of diversity – gender and culture?

- Are you able to identify how words matter in promoting safety, trustworthiness, and inclusion?

- Are you able to identify common strategies for attending to diversity, gender equity, cultural responsiveness, and inclusion?

Supplementary Resources

Stereotypes and Stigma

- Understanding Stigma (Mental Health Commission of Canada)

- Addressing Stigma: Towards a More Inclusive Health System (The Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2019)

- Building a Foundation for Change: Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy 2019–2022 (Government of Canada)

Resources for Gender-Informed Practice

- LGBTQI2S Terms and Concepts (Egale)

- TrueChild: Our Reports (TrueChild Website)

- Gender Unchained: Notes from the Equity Frontier (By Lorraine Greaves and Nancy Poole, Friesen Press)

Cultural Safety, Reconciliation and Decolonization

- Cultural Safety and Humility Resources (First Nations Health Authority)

- Reconciliation in Action: A National Engagement Strategy (Reconciliation Canada)

- Decolonization (British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner)

Glossary

Awareness: A principle for interacting with therapy dog program participants related to how much knowledge you have about the beliefs, experiences, and needs of the individuals you are engage with.

Colonization: A process where members of one cultural group displace and take domination over another cultural group.

Competence: A principle for interacting with therapy dog program participants related to how effective your interactions will be given the specific beliefs, values, and needs of the individuals you are visiting with.

Decolonization: Processes to allow groups that were colonized to revitalize their cultural beliefs and be empowered to determine ways of living that align with their own perspectives and interests.

Humility: A principle for interacting with therapy dog program participants related to how well your interactions with them reflect your awareness that your knowledge can always expand and a willingness to let individuals educate you.

Reconciliation: A process whereby Indigenous peoples and Canadians work together to recognize the negative impact of colonialism and develop relationships based around mutual recognition and respect.

Safety (Responsiveness): A principle for interacting with therapy dog program participants related to how well your interactions align with the beliefs and practices that are significant for the group you are engaging with.

Sensitivity: A principle for interacting with therapy dog program participants related to how well your interactions reflect an understanding and appreciation of the beliefs, values, and needs of a distinct population.

Stereotypes: The widely recognized and oftentimes negative beliefs and assumptions people have about members of certain social groups.

Stigmatization: A process where widely recognized stereotypes justify the mistreatment and social inequality of certain social groups.

References

Anna-Belle the Therapy Dog, G.S. Sewap, C. Dell, B. McAllister and J. Bachiu. 2018. “’She Makes Me Feel Comfortable’: Understanding the Impacts of Animal Assisted Therapy at a Methadone Clinic”.Journal of Indigenous HIV Research 9: 57-65 <https://www.ahacentre.ca/uploads/9/6/4/2/96422574/%E2%80%9Cshe_makes_me_feel_comfortable%E2%80%9D-_understanding_the_impacts_of_animal_assisted_therapy_ at_a_methadone_clinic.pdf>

Blakemore, E. 2019. “What is Colonialism?”. National Geographic Online <https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/colonialism>

Canada’s History. 2022. “Every Child Matters Educational Package”. Canada’s History Website < https://www.canadashistory.ca/education/classroom-resources/every-child-matters-en/every-child-matters-educational-package >

CBC News. 2004. “Sask. Town bans ‘dangerous’ dog breeds”. CBC News Online <https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sask-town-bans-dangerous-dog-breeds-1.489531https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sask-town-bans-dangerous-dog-breeds-1.489531>

Chilisa, B. 2019. Indigenous Research Methodologies. Los Angeles, Sage Publications

Dell, C. A., D. Chalmers and H. Goodfelow. 2019. Animal Memories. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan < https://www.flipsnack.com/harperg/animal-memories-fcfexaf97/full-view.html>

Drabish, K and L. Theeke. 2022. “Health Impact of Stigma, Discrimination, Prejudice, and Bias Experienced by Transgender People: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies”. Issues in Mental Health Nursung, 43(2): 111-118. DOI: 10.1080/01612840.2021.1961330

Government of Canada. 2020. “LGBTQ2 terminology – Glossary and common acronyms” Government of Canada Website <https://women-gender-equality.canada.ca/en/free-to-be-me/lgbtq2-glossary.html>

Government of Canada. 2019. Addressing Stigma: Towards a More Inclusive Health System The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2019. Government of Canada Website, <https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/addressing-stigma-toward-more-inclusive-health-system.html>

Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. 2017 “A Brief Definition of Decolonization and Indigenization”. ICT Website < https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/a-brief-definition-of-decolonization-and-indigenization>

Joseph, B. 2016. “21 things you may not know about the Indian Act” CBC News Online <https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/21-things-you-may-not-know-about-the-indian-act-1.3533613>

Judd, A. 2021. “Punished and hit for speaking her language, a B.C. residential school survivor is not staying silent. Global News Online <https://globalnews.ca/news/7981899/residential-school-survivor-speaking-out-conditions-trauma/>

Major B, O’Brien LT. 2005. “The Social Psychology of Stigma”. Annual Review of Psychology. 56:393-421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. PMID: 15709941.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. 2022. “Stigma and Discrimination”. Mental Health Commission of Canada Website <https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/what-we-do/stigma-and-discrimination/>

Merino, Y., L. Adams and W. Hall. 2018. “Implicit Bias and Mental Health Professionals: Priorities and Directions for Research. Psychiatric Services, 69: 723-737 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700294

Provincial Government of British Columbia. 2020. In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Healthcare. <https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Summary-Report.pdf>

Reconciliation Canada. 2022. “Reconciliation Canada: History and Background. Reconciliation Canada Website, <https://reconciliationcanada.ca/about/history-and-background/our-story/>

Regina Humane Society. 2022. “Breed Specific Legislation” Regina Humane Society Website <https://reginahumanesociety.ca/about-us/about-the-rhs/position-statements/breed-specific-legislation/>

Fudge Schorman, A. 2014. Stigmatization. In: Michalos, A. (eds) “Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2871

Stangl, A, V. Earnshaw et al. 2019. “The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development and policy on health-related stigmas”. BMC Medicine 17:31

Whitehead, J. J. Shaver and R. Stephenson. 2016. Outness, Stigma and Primary Health Care Utilization among Rural LGBT Populations PLoS ONE 11(1).