Developed by:

M. D. Daschuk, PhD, Department of Sociology; University of Saskatchewan

Colleen A. Dell, PhD, Department of Sociology; University of Saskatchewan

Erin Beckwell, MSW, RSW (SK), Faculty of Social Work, University of Regina

Reviewers:

Maryellen Gibson, MPH, Department of Sociology; University of Saskatchewan

Therapy Dog Handler Reviewer:

Jane Smith, B.Trad., B.Ed, MStJ; St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Program

Introduction

In this module you will have the opportunity to increase your awareness and skills about mental health among the people that you and your therapy dog are visiting with. Particular attention is paid to stress and trauma and how they can impact a program participant’s thinking and behavior. You will also have the opportunity to review how to effectively respond to an individual with mental health needs. The expertise of Erin Beckwell is featured in this module, guiding you through mental health basics, so you can be the most effective therapy dog visiting team possible.

Figure 3-1: Erin and Reilly. Permission: Courtesy of Erin Beckwell, Faculty of Social Work, University of Regina.

EXPERT SPEAKER: About Erin Beckwell

Erin is a queer social worker living and working on Treaty 6 territory and the homeland of the Métis in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Erin has spent her career promoting and working alongside diverse communities, offering anti-racism education, advocating for harm reduction, and supporting trauma-informed care. Currently, Erin is a Clinical Instructor with the Faculty of Social Work at the University of Regina and a consultant focusing on trauma education. Fun fact: Erin and her wife Lisa were the first gay couple to be legally married in Saskatchewan in 2004.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to:

- Define mental health, stress, and trauma.

- Describe how stress and trauma can impact thoughts, perceptions, and actions.

- Identify stigmatizing language surrounding mental health and alternate terms to use.

- Apply strategies for working with therapy dog program participants in trauma-informed and destigmatizing ways.

- Mental health

- Stress

- Anxiety

- Crisis

- Trauma

- Trauma-informed

Essential Information for Therapy Dog Handlers

Click to expand each section.

Key Terminology for Therapy Dog Handlers

As a therapy dog handler, you are already well aware that you, other handlers, and your canine ‘compawtriots’ (compatriots) visit a range of places, including prisons, children’s hospitals, university campuses, and older adult retirement communities. The people you meet in these spaces can have varying mental health needs. This can range from university students experiencing stress when writing their final exams, through to individuals and even communities dealing with the aftermath of a tragedy. A therapy dog handler can best offer comfort and support to the people they are visiting with by being aware of the signs and symptoms associated with human mental health needs.

Everyday conversations surrounding the situations you find yourself in with your dog often include terms we use broadly in everyday conversations, but these terms have very specific meanings among health care professionals and therapeutic service providers. It is useful, therefore, to consider how common terms – like mental health, stress, anxiety, crisis, and trauma – are defined by professionals.

Mental Health

The Canadian Mental Health Association defines mental health as “a state of well-being [based in] our emotions, feelings of connections to others [and ability] to manage life’s highs and lows” as influenced by environmental factors, including “safe and affordable housing, meaningful education and employment, leisure activities, the support of a community, access to land and nature, freedom from violence, and good access to health care and mental health services” (2021). Our mental health is strongest when we have reassurances about our safety and security, can keep a positive attitude, and the connections we have with those we care about continue, including our companion animals.

It follows that our mental health is negatively influenced when these factors are absent or threatened. This could include, for example, if our employment and standard of living suddenly become unstable, or we lost a person or animal who is important to us. We also need to recognize that many individuals do not have a lot of positive experiences and social supports that help them maintain a positive attitude, feel safe, or connected with others. Consequent feelings of insecurity and isolation can contribute to the development of a set of problematic behaviors to cope, such as using substances in an unhealthy way and can have a further negative influence on their mental health.

Stress and Anxiety

We have all experienced stress and anxiety; two closely related and what seem to be increasingly common feelings that can have a negative impact on our mental health. From a mental health perspective, stress can be defined as “the body’s response to a real or perceived threat [meant] to get people ready for some kind of action to get them out of danger” (CMHA, 2016). To distinguish between stress and anxiety, think about the differences between our patterns of thinking and the physical sensations we experience as a result. Whereas stress is related to our thinking, anxiety is more closely related to the physical responses we experience in our body because of stress. It is stress that keeps us up at night thinking about the challenges of the day ahead, and it is anxiety that causes us to have dizzy spells or shortness of breath as we encounter stress in the moment.

Crisis and Trauma

As with stress and anxiety, the concepts of crisis and trauma are closely related but also distinct. The term crisis is commonly used to refer to the onset of difficult situations that can negatively influence our mental health. A crisis is a situation that is happening at the moment, and is impacting an individual emotionally, physically, mentally, and/or spiritually. A crisis can emerge in a variety of forms, such as with the onset of an event or situation that threatens our personal safety and security or that endangers significant people and relationships in our lives.The duration of a crisis can range from short-term (such as an accident) to long-term (such as being subject to longstanding patterns of abuse in a home environment).

Trauma refers to the lasting influence that experiencing a crisis – or significant stress for a prolonged period – can have on an individual’s physical, mental, emotional, and/or spirtual health as they continue on with their daily lives. Defined by the Canadian Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, “trauma is the lasting emotional response that often results from living through a distressing event. Experiencing a traumatic event can harm a person’s sense of safety, sense of self, and ability to regulate emotions and navigate relationships. Long after the traumatic event occurs, people with trauma can often feel shame, helplessness, powerlessness and intense fear” (CAMH, 2022).

Later in this module we will elaborate on the types of trauma that people you visit with may be experiencing and the ways it may be informing their thoughts and actions. For now, let’s begin by reviewing some examples of how you and your therapy dog ‘pawtner’ (partner) will be able to assist and support therapy dog program participants, should they be in crisis, experiencing trauma, or encountering stress and feelings of anxiety.

Trauma-Informed Strategies for Therapy Dog Handlers

The following two examples – one at a federal correctional facility and the other at a vaccination clinic – demonstrate the therapeutic benefits and positive outcomes associated with therapy dogs involved in an animal assisted activity, These examples also highlight the important role that handlers play in providing environments that help participants feel safe, empowered, and accepted.

Example 1: Six Strategies

As a therapy dog handler, you no doubt frequently meet individuals that can benefit profoundly from an opportunity to make meaningful connections with you and your canine partner. Let’s take the time to review one example. St. John Ambulance therapy dog Kisbey and her handler visited a federal correctional institution in Saskatchewan to spend time with clients with a wide range of unique needs. They interacted with participants described as having “complex mental health needs including self-harm, childhood trauma, mental illness, substance abuse, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)” (Dell and Poole, 2015, p. 2). The team sought to recognize and respect the unique conditions and needs of the participants by engaging with six trauma-informed strategies in their interactions: establishing relationships built around safety, promoting trustworthiness, providing peer support, allowing for collaboration and mutuality, providing safe spaces for empowerment, voice and choice, and respectfully recognizing cultural, historical, and gender issues. In a subsequent study of their visits, participants expressed how making connections with Kisbey – in the respectful, non-judgmental environment – had a positive influence on their mental health. They also acknowledged how Kisbey as a therapy dog uniquely contributed to that supportive environment in ways that only a dog can.

Review the following trauma-informed strategies for interaction, as adapted from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) Trauma Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services: A Treatment Improvement Protocol.

1. Safety: Ensure that clients and all participants involved in the interaction feel safe and secure.

2. Trustworthiness: Clients and all participants should build trust by being honest and open about the organization and intent of all aspects of the interaction.

3. Peer Support: Clients should be granted support in the manner they identify.

4. Collaboration and Mutuality: Clients should feel free to contribute to the organization of the interaction as equal partners.

5. Empowerment, Voice, and Choice: Clients should be granted opportunities for self-empowerment and a celebration of their strengths and resiliency.

6. Recognizing Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues: Clients should be treated to interactions that are sensitive to their beliefs and identities.

Example 2: The CARD System

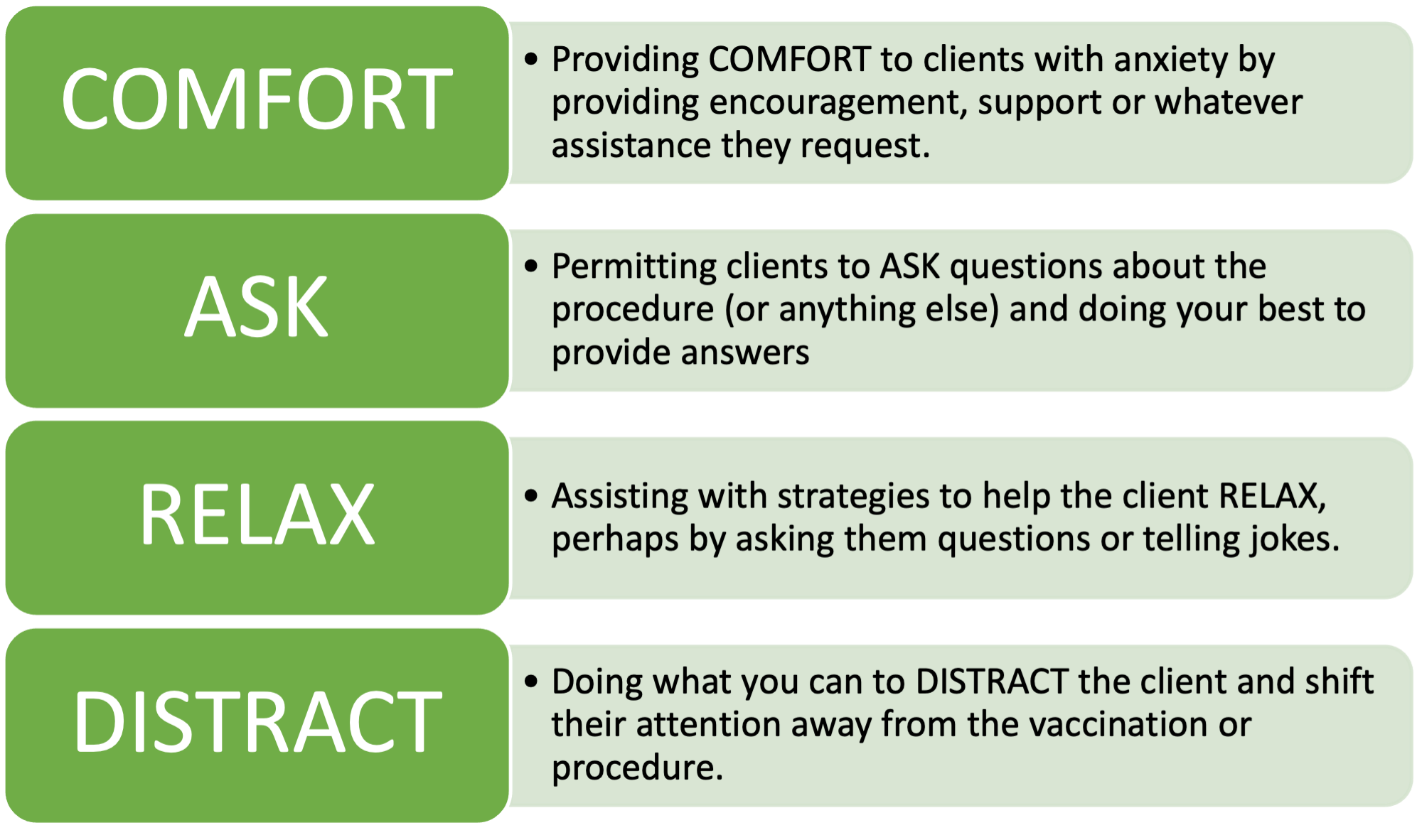

On other occasions, as a second example, you and your therapy dog may have an opportunity to assist people by alleviating anxieties associated with stressful situations. In 2021, St. John Ambulance dispatched a number of therapy dog teams to COVID-19 immunization clinics throughout Saskatoon and Regina to help alleviate fears for vaccine resistant patients and the stress of clinic healthcare providers. These dogs and handlers endorsed best-practices associated with the CARD system: therapy dogs provide comfort, relaxation and distraction while handlers ask vaccine recipients if they wish for canine companionship and respond to questions about the dogs.

Figure 3-1: The CARD System. Permission: Courtesy of Colleen Dell, Department of Sociology, University of Saskatchewan, based on About Sick Kids (2022) – The Card System Learning Hub at https://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/card/

In many cases, your therapy dog partner provides comfort, relaxation and serves as a distraction, but it likely depends on you to consider and respond to any questions the vaccination clients may ask about being a therapy dog team! You can review the article How therapy dogs are helping to reduce needle fear at a COVID-19 vaccination clinic (Canadian Nurse) for some more specific examples from members of our team.

Handler Story (Womble and Wendi Stoeber)

Before we move on to discuss trauma-informed practice in more detail, consider this first-person account of the impact therapy dogs and their handlers can have for people experiencing a crisis. Pay particular attention to what therapy dog handler Wendi Stoeber learned from her experiences visiting with Womble during a Saskatchewan crisis.

Please watch the following video.

Written content and video by Wendi Stoeber

Who are you?

My name is Wendi Stoeber & I am a St. John Ambulance therapy dog handler. I have been retired for a while now from a long career in health care.

Who is your therapy dog?

This is Womble. He and I have been a therapy dog team since 2018. He is an 11 year old Standard Poodle. In addition to visiting with people as a therapy dog, he really enjoys participating in the dog sport agility where he gets to jump over and run through obstacles!

What are you going to share?

I would like to share a few stories about important things that I experienced in one particular community visit with Womble. These stories illustrate how Womble provides a particular type of comfort and support to people he visits with, as well as the need for therapy dog handlers to have a basic understanding of mental health, coping and its various presentations in the people they visit with.

Several years ago there was a horrific collision between a semi trailer/truck and a bus carrying a Canadian Junior ‘A’ ice hockey team. 16 were killed & 13 injured, many very seriously and the tragedy made world news. The team was based in and represented a small city and its surrounding rural area. Hockey is a BIG deal there. Two days following the collision the town held a memorial service at its large hockey arena. St. John Ambulance Therapy Dog Teams were asked by the mayor to provide support to those attending. Womble and I had only recently certified as a team. I had experience working with people in stress and confidence in my dog’s abilities and our strength as a team, but this would be a challenge considering the circumstances.

Driving to the event with 2 other experienced handlers and their dogs helped us feel part of a larger team and the discussions we had on the road helped me to understand & clarify what would be expected of us. I was grateful for that opportunity since it smoothed the way considerably.

But there was little that could prepare us for the emotion in that arena. Womble had plenty of crowd experience, but not at that level, and certainly never had been in a large, concrete arena, let alone one packed with grieving people. Even his size made it difficult for him to maneuver some areas comfortably, so there was a bit of trial and error as we learned what would work for us. He was new to the job and I was amazed to watch him figure out what was needed from him and to see him approach people that he sensed needed his calming presence.

I watched him lay on the floor while a young child patted and cuddled with him for close to half an hour during the actual service. At first it felt like we were babysitting – not a problem since it allowed parents to immerse themselves in the service. However, while this little girl patted Womble, along with the general kid chit chat, she volunteered how sad her mom was about everything that had happened and we were able to quietly talk a bit about that & how it was OK to be sad. I realized that Womble was being more than a useful distraction. She had some worries & through the physical interaction with him she felt free to talk about them. He was providing comfort & support for her as well as being a useful distraction. After a while she skipped off to go give her mom a hug.

In another instance I observed Womble quietly enter a tight circle of intense young men talking and just calmly stand there until slowly they started reaching down & patting him without even realizing what they were doing. I just let him do his thing; I’m not sure they even knew I was there.

Later on a mental health care worker who had been working throughout the weekend came by & joked about needing to take a break for some dog therapy herself. I assured her that the dogs were there for everyone. She put her arms around Womble & hugged him for a while. Soon the tears began to roll down her cheeks as the emotion of the whole situation and the work she had been doing overwhelmed her. She took the time that she needed while Womble quietly oozed empathy and care. I had known what he was capable of but he surpassed my expectations. My heart filled with love and admiration at his skill.

It was a challenging day for both of us, but we looked out for each other. He provided support, comfort and inspiration for me as we navigated it together. The long drive home with the others allowed us to decompress & debrief; telling our stories, and just winding down with the feeling that our dogs had done something to help ease the grief for many people.

What do you wish you knew at the time?

In retrospect, I think something that would have been helpful for me to know at the time was the impact that this sort of group grief can have and how people can allow themselves to feel vulnerable & reach out for the comfort of a therapy dog when they might not typically do that. Although I had experience, in this situation it was my partner, Womble who was providing the comfort and support and I needed different strategies to enable and guide the interaction with him.

Program Participant Perspectives (Speaker – Erin Beckwell)

Next, Erin Beckwell’s presentation provides a thorough overview of different forms of stress and trauma and how they can influence behavior in people, including people you meet as a therapy dog handler. She also looks at how different forms of stress and trauma might be shaping your own behavior, revisits the importance of using destigmatizing language, and highlights strategies to help you and your therapy dog provide trauma-informed comfort and support to the people you visit with.

Introduction, Definitions, and Overview of Trauma

Please watch the following video.

Erin has made some important points about the different ways stress and trauma can be experienced. Here is a summary of terms and definitions she presented to refer to as you continue through the activities in this module:

- Eustress Response: A reaction to stress that (usually) has a positive influence on people. A eustress response produces excitement and provides motivation.

- Distress Response: A reaction to stress that (usually) has a negative influence on people. A distress response produces anxiety and provides apprehension.

- Trauma Response: A reaction to overwhelmingly distressing experiences that negatively influence a person’s ability to cope. A trauma response produces feelings of insecurity and threatens mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual well-being.

- Immediate Trauma Response: Trauma responses inspired by a disturbing event or set of circumstances that a person has recently experienced.

- Delayed Trauma Response: Trauma responses inspired by a disturbing event or set of circumstances that a person has experienced in the past.

- Persistent Trauma Response: Trauma responses inspired by a disturbing event, series of events, or circumstances that effect a person repeatedly throughout the remainder of their lives.

Erin also addresses Intergenerational Trauma and Historical Trauma in her video. The 2015 reports from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s investigation into Canada’s residential school system has informed a wider understanding of how the horrific legacy of colonialism directly influences forms of trauma that impact First Nations, Inuit, and Métis populations today. As we noted in the last module, therapy dog handlers in Saskatchewan and other parts of Canada interact with therapy dog program participants who are experiencing ongoing trauma related to colonialism.

Intergenerational trauma occurs when the effects of trauma by those who have experienced it passes down generationally. This can occur by witnessing patterns of conduct that align with trauma-exposed behavior, being subject to abusive behavior by individuals who have been trauma-exposed, and/or through changes at the cellular levels with trauma-exposed family members (DNA – deoxyribonucleic acid).

Historical trauma is the process through which a history of inequitable, and oftentimes dehumanizing, relations between a powerful group of people and a disempowered group of people has a cumulative, multigenerational traumatic impact on the less powerful group.

To learn more about these forms of cultural trauma and their connection to Canada’s commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, a variety of reports and resources can be accessed through the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

How Trauma Can Impact Thoughts, Perceptions, and Actions

Now that we have a clearer understanding of trauma and the different ways in which trauma can be experienced, let’s move on to Erin’s overview of the types of trauma-influenced responses people often have.

Please watch the following video.

To this point, we have:

- defined mental health, stress and trauma,

- identified three ways people experience trauma (Eustress Response, Distress Response, Trauma Response),

- classified the timing of individuals’ responses to trauma (Immediate Trauma Response, Delayed Trauma Response, Persistent Trauma Response), and

- considered how people respond to trauma in line with four ‘patterns of protection’, including fight, flight, freeze, and fawn.

Let’s do an activity now to practice how you as a therapy dog handler can identify the mental health needs and behaviors of the individuals you visit with.

Destigmatizing or Reframing Language

You likely noticed that Erin’s discussion of the four Fs touched on the topic of stigma. Earlier in module two, we discussed destigmatizing language related to personal attributes like sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, culture, religious perspective, ability, and age. In this next video, Erin touches on destigmatizing language related more specifically to mental health and substance use disorders.

Please watch the following video.

This table presents some alternatives to stigmatizing terms commonly used with mental health and substance use disorders.

Table: Destigmatizing Language 2: Destigmatize Harder

| Stigmatizing Language | Destigmatizing Alternatives |

| Addict | Person with substance use disorder |

| Alcoholic | Person with alcohol use disorder |

| Committed suicide | Died by suicide |

| Drug problem, Drug habit | Substance use disorder |

| Drug abuse | Drug misuse, Harmful use |

| Failed/Unsuccessful suicide attempt | Attempted suicide |

| Former/Reformed addict, Alcoholic | Person in recovery |

| Mentally ill, Insane person | Person living with a mental health problem or illness |

| Suffers from/with depression | Lives with/Is experiencing depression |

Source: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2014; Mental Health Commission of Canada (2020).

Remaining Strategies for Trauma-Informed Practice

The final section of Erin’s video continues on to highlight the importance of providing feel safety, choice, and control.

Please watch the following video.

Now that you are familiar with strategies related to trauma-informed practice, we can return to the hypothetical scenarios considered earlier. Using a piece of paper, please reflect on how you could best provide trauma-informed services to the individuals you were introduced to in the previous five scenarios. When you are ready, you can click to reveal a suggested response for each scenario.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

On one hand, trauma is a complex force that can impact people in unique ways and inspire different responses. On the other hand, people experiencing trauma commonly face feelings of disempowerment, lack control, and can have a hard time coping. Overall, trauma is experienced and expressed in a variety of ways, but a trustworthy first step toward meaningful interactions with the people we visit with who have experienced trauma is to be trauma-informed.

Erin’s talk on how to provide trauma-informed assistance coincides closely with the stories shared in this module. Kisbey and her handler tried to ensure participants felt safe and empowered when visiting a correctional facility. Therapy dog Womble and his handler provided support to a community in crisis that aligned with universal precautions based around being present without being intrusive. In each of these cases, and many others therapy dogs team across the country experience each and every day, responses based in principles of safety, choice, and control can assist people who are experiencing complex mental health needs.

Erin’s presentation also touched on the important topic of ensuring your own mental health is maintained as you and your therapy dog ‘emBARK’ (embark) on your visiting adventures. Module four discusses various ways of thinking about your own health and wellbeing as a therapy dog handler, explains what vicarious trauma is, and ‘debRUFF’ (debrief) you on some strategies to maintain self-care.

Discussion/Self-Reflection Questions

- Are you able to define mental health, stress and trauma?

- Are you able to describe how stress and trauma can impact thoughts, perceptions and actions – those of people you’re supporting/working with, and your own?

- Are you able to identify stigmatizing language surrounding mental health and alternate terms to use?

- Are you able to apply strategies for working with therapy program participants in trauma-informed and destigmatizing ways?

Supplementary Resources

Trauma-Informed Practice

- Trauma-Informed Practice Guide (BCCEWH)

- Manitoba Trauma Information & Education Centre – home of the Trauma-Informed Toolkit

- Trauma-Informed Practice Principles: Self-Reflective Questions (BCCEWH)

- Trauma-Informed Self-Assessment Tool (Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence)

Intergenerational Trauma, Historical Trauma and Reconciliation

- TRC Website (University of Manitoba/National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

- Reconciliation Canada Website

- Intergenerational Trauma: An Animated Short (The Healing Foundation; Hosted on Youtube.com)

Destigmatizing Language

- Language Matters (Canadian Public Health Association)

- Overcoming Stigma Through Language: A Primer (Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction)

- Safer Language Reference Guide (Mental Health Commission of Canada)

Glossary

Anxiety: Physical symptoms associated with feelings of stress.

Crisis: The onset of a threatening, traumatic situation.

Mental health: Personal well-being based on a positive outlook, satisfaction with life, and connection with others.

Stress: Mental, emotional, and physical responses to perceived threats and difficult situations.

Trauma: The lasting impact a negative experience, series of experiences, or set of circumstances can have on mental health, and the ability to cope.

Trauma-informed: Ways of providing services that recognize and respect the influence trauma can have on people’s lives and behaviors.

References

About Sick Kids. 2022. “The Card System Learning Hub”. About Sick Kids Website, https://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/card/.

Bombay, A., K Matheson and H. Anisman. 2009. “Intergenerational Trauma: Convergence of Multiple Processes among First Nations peoples in Canada”. Journal of Aboriginal Health 5(03): 6 – 47.

Canadian Center for Addictions and Mental Health. 2022. “Trauma”. CAMH Website, https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-illness-and-addiction-index/conditions-and-disorders/trauma.

Canadian Mental Health Association. 2021. “Facts About Mental Health and Mental Illness”. Canadian Mental Health Association Website, https://cmha.ca/brochure/fast-facts-about-mental-illness/.

Canadian Mental Health Association. 2016. “Stress”. Canadian Mental Health Association Website, https://cmha.ca/brochure/stress/.

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2017). Changing the language of addiction (fact sheet). https://www.ccsa.ca/changing-language-addiction-fact-sheet

Dell, C. A, M. Gibson, B Carey, H Mackenzie, S. Peachey, L. Williamson and D. Chambers. 2022. “How therapy dogs are helping to reduce needle fear at a Covid-19 vaccination clinic”. Canadian Nurse, https://www.canadian-nurse.com/blogs/cn-content/2022/03/28/how-therapy-dogs-are-helping-to-reduce-needle-fear.

Dell, C. A. and N. Poole. 2015. “Taking a PAWS to Reflect on How the Work of a Therapy Dog Supports a Trauma-Informed Approach to Prisoner Health”. Journal of Forensic Nursing, DOI: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000074

Mental Health Commission of Canada. 2020. “Combat Mental Health Stigma with a Shift Towards People-First Language”. Mental Health Commission of Canada Website, https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/blog-posts/21408-combat-mental-health-stigma-with-a-shift-towards-people-first-language/.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2014. “TIP 57 Trauma Informed Care in Behavioral Services: A Treatment Improvement Protocol”, SAMHSA Website, https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4816.pdf.