Overview

As discussed in earlier modules, Canada is a multinational state. It was constituted by the English and French colonies, and built on the treaties made with the Indigenous peoples that were here before them. Canada has been a destination state for immigrants ever since. The earliest immigration policies encouraged Europeans to resettle in Canada and sought to reinforce colonial land claims as well as exploit Canada’s abundant natural resources for European investors. European settlers would remain the norm, including the loyalists fleeing the American Revolution, until the 1950s and 60s. Subsequently, European immigrants would be joined by the refugees generated by ethnic and ideological conflict around the world. Notable moments of immigrant influx include: the Ismaili Muslims fleeing Uganda in 1972-3, Iranians fleeing revolution in 1979, the 60,000 Vietnamese Boat People fleeing the Communist Vietnam in 1979-80, asylum seekers from around the world in the 1980s, the 5000 Kosovars fleeing war in 1999, the 3900 Karen from refugee camps in Thailand, the 23,000 Iraqi refugees in 2015, and the 40,000 Syrian refugees accepted between 2015-17. On average, 250,000 immigrants a year resettle in Canada and, according to the 2016 census, 21.9% of Canadians are now immigrants. However, Canadians are still locked into its founding debates; the debate between English and French Canada as well as the debate between the Canadian state and the Indigenous Peoples in Canada, as we covered in Module 10.

Figure 11-1: "Canada Without Quebec Flag Map" Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AFlag_Map_of_Canada_(with_Independent_Quebec).png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Kacnepcku-Cp6uja.

This module will focus on Québec and the English/French debate. Québec is the institutional representation of French Canada. It has fought for the rights of the French language and the province as a whole. Many in Québec subscribe to the compact theory of confederation, which argues that Canada was co-founded by the English and French. From this perspective, the English and French nations are equal and primary, subsuming all other debates within the Canadian multicultural construct. This English/French tension would subsequently be central to contemporary Canadian political debates, including the issue of language rights in the provinces to the 1995 Québec Referendum on sovereignty. In order to assess the role of Québec in Canada, this module will look at Québec’s history, the roots of Québec nationalism, and modern Québec nationalism.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Identify the roots of Québec nationalism

- Discuss the evolution of French nationalism from Confederation to the 1995 Referendum

- Discuss the impact of the patriation of the Constitution as well as the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords on contemporary Québec nationalism

- Read “Chapter 5 – Québec Nationalism”

- Complete Learning Activity 11.1

- Complete Learning Activity 11.2

- Complete Learning Activity 11.3

- Bilingualism

- Bloc Québécois

- Charlottetown Accord

- Charte de la langue française

- Clarity Act

- Compact theory of confederation

- Conscription

- Conscription Issue

- Disallowance

- Distinct society

- Francization

- Front de libération du Québec (FLQ)

- Lord Durham Report

- Lower Canada

- Meech Lake Accord

- National self-determination

- New France

- Official Languages Act

- Parti Québécois

- Province of Canada

- Québec Act of 1774

- Québec referendum of 1995

- Quiet revolution

- Red River Rebellion

- The Manitoba School Issue

- Upper Canada

- Union Act of 1841

- Union government

- 1980 Québec referendum

- Text Book Chapter 5 – Québec Nationalism

Learning Material

There have been several contemporary attempts to form an independent state from an established western liberal democracy in the past few years. Most recently, the Catalonians held a referendum on independence from Spain on October 1st, 2017. Scotland held a similar referendum on independence from the UK on Sept 18th, 2014. Belgium has recurring tension between its Flemish and Walloon communities with many arguing the indeterminant status of Brussels is all that has kept the country together.

Figure 11-2: “Catalan Independence” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AHolding_Hands_for_Catalan_Independence_NYC_2.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Liz Castro.

Figure 11-3: “Scottish Independence” Source: https://flic.kr/p/gc11FY Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Maria Navarro Sorolla.

Figure 11-4: “Canadian Forces deployed downtown Montreal during the October Crisis” Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Soldier-and-child-octcri.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

All of these attempts are rooted in nationalist exercises, whereby a common ethnicity which constitutes a minority group within a state, reacts against some common grievance, seeking territorial autonomy or sovereignty. In essence, a perceived ethnicity or nation within a larger state is seeking self-determination. The Québécois too have sought for national self-determination, almost taking the first step towards some form of sovereignty association via a referendum in 1995. As in some of the aforementioned cases, Québec has developed political parties, nationalist and cultural associations, and even a designated terrorist organization to pursue their self-determination. Provincially, the Parti Québécois (PQ) was established in 1968 to pursue a sovereigntist agenda. Federally, the Bloc Québécois was established in 1991 to both support the PQ in its sovereigntist agenda as well as to promote Québec’s interests at the national level. In terms of nationalist and cultural associations, the government of Québec has spent serious resources on establishing 23 diplomatic offices around the world with immigration and trade advisors and even quasi-ambassadors.

In the 1960s, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) was founded to fight Anglo-Saxon imperialism, overthrow the state, and replace it with a Marxist inspired workers’ society. It was subsequently declared a terrorist organization for its violent attacks, in particular the bombing of the Montreal Stock Exchange in 1969 and the October Crisis of 1970. In order to understand the establishment of the PQ and the BQ, the establishment of diplomatic offices, the FLQ’s fight against Anglo-Saxon imperialism, and the two sovereignty referendums, this module will briefly look at the history of Québec nationalism, early French-English conflict, and modern Québec nationalism.

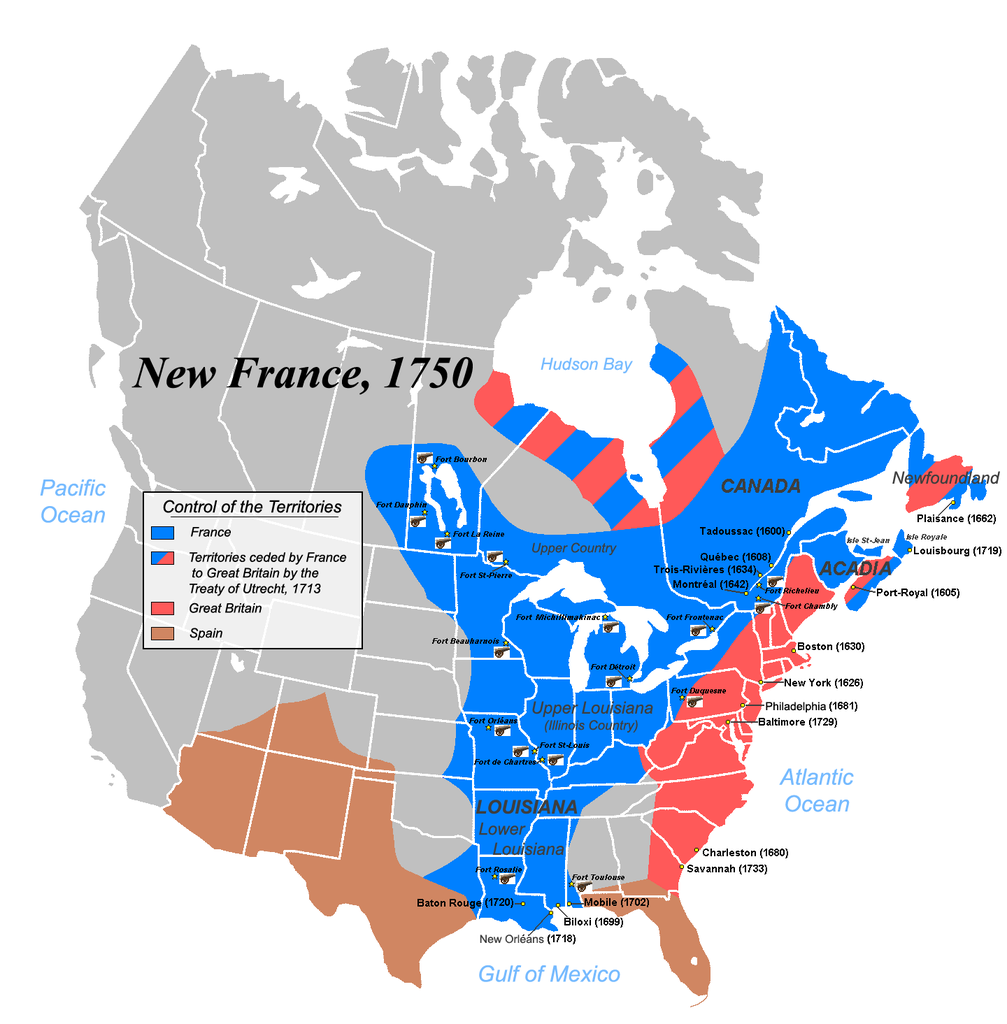

Québec has been the institutional defender of French rights in Canada since its inception. It was initially the colony of New France, with first contact being made by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and Samuel de Champlain making France’s territorial claim on what would become Québec in 1608. With the Treaty of Paris in 1763, New France ceased to exist, being ceded to Britain. Despite fears to the contrary, the French population was able to maintain their language, religion, and legal traditions. This was largely due to the tension between the British and the Thirteen Colonies. In an attempt to constrain the expansionist moves of the Thirteen Colonies as well as to punish them for protests such as the ‘Boston Tea Party’, the British legislated the Québec Act of 1774. Amongst other things, it sought to placate the French Catholics of former New France in case of further instability in the American colonies. In order to do so, the Québec Act removed any reference to the Protestant faith in the oath of allegiance, allowed religious freedom concerning the Catholic faith, and restored the use of French civil law. Importantly, this established the duality of British and French social, political, and economic structures that would set the stage for subsequent tensions between English and French Canada.

Figure 11-5: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New-France1750.png Permission: CC-BY-SA-3.0 Courtesy of JF Lepage.

Following the American Revolution, the borders of Lower Canada (Québec) and Upper Canada (Ontario) were established with the Constitutional Act of 1791. Between 1791 and 1867, tensions arose over the issue of self-government with rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada in 1837-38. It is during this time that French nationalism began to take shape, with demands for an autonomous state.

Figure 11-6: “Battle of Saint-Eustache” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint-Eustache-Patriotes.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

The Lord Durham Report of 1839, commissioned to investigate the rebellions, recommended joining Upper and Lower Canada and instituting responsible government which was achieved in the Union Act of 1841, forming the Province of Canada. Both the Lord Durham Report and the creation of the Province of Canada had the explicit aim of assimilating the French. This assimilationist aim would create a backlash in the French community, cementing the nationalist sentiment. This sentiment would take several forms. Its earliest form was strictly the objective of an autonomous state. While this objective of achieving a state has never fully subsided, subsequent forms would be defined more culturally, through language, religion, laws, and traditional practices. These two forms still co-exist. The one seeking a sovereign state. The other seeking to establish the French nation as a community protected constitutionally within the construct of Canada.

Confederation, or the British North American Act of 1867, was a defining moment for French speaking Canada. They saw it as an agreement between two founding nations and therefore gave both the English and the French a practical veto on the subsequent development of the Canadian state. A position which would be much tested, especially with the patriation of the Constitution in 1982. It also firmly put the English/French tension at the top of the hierarchy of Canadian issues. However, this was not a commonly held view in English speaking Canada which saw Confederation as creating a homogenous state composed of different provinces representing different regions/interests.

Figure 11-7: “The Fathers of Confederation” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AFathers_of_Confederation_LAC_c001855.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of James Ashfield.

Put together these three events would set the stage for French-English conflict in Canada. The Québec Act of 1774 recognized the rights of French Speaking Canada, particularly in the area of language rights, religious freedom, and the use of French civil law as the basis of private law. This would become the baseline expectation of French speaking Canada in all subsequent political negotiations. The explicit attempt to assimilate the French speaking community by creating the Province of Canada in 1841, facilitated the entrenchment and legitimation of French nationalism. For some French nationalists, the explicit attempt to assimilate French speakers in the majority English state necessitated the fight for an autonomous state. For others, this attempted assimilation required the legal and political protection of the French language, religion, laws, and traditional practices. These differing visions of French nationalism still play out in the contemporary debate on whether it can be achieved within the construct of Canada or whether it requires establishing a sovereign Québec. Finally, the entrenchment of the tension between French and English Canada in the process and outcome of Confederation itself, has privileged this divide over all others. Any discussion of the federal-provincial relationship, constitutional reform, or appointment of key public servants, is first seen through the prism of the French-English tension. It has obscured important issues such as the relationship between the Canadian state and Indigenous peoples since all other political issues in Canada are subsumed by this primary tension.

Watch ‘Confederation: the creation of Canada’ by The McCord Museum:

Use the following questions to guide a post to your Learning Activity Discussion Board.

- According to the video, what differing role has the narrative of Confederation played in Canadian histories?

- Particularly, how is Confederation seen in Québec?

- What were the catalysts towards creating a Canadian union?

- What are the pre-confederation grievances of French Canada against English Canada?

- What role do French Canadians see the Catholic Church and government playing?

- What are the essential terms of Canadian Confederation?

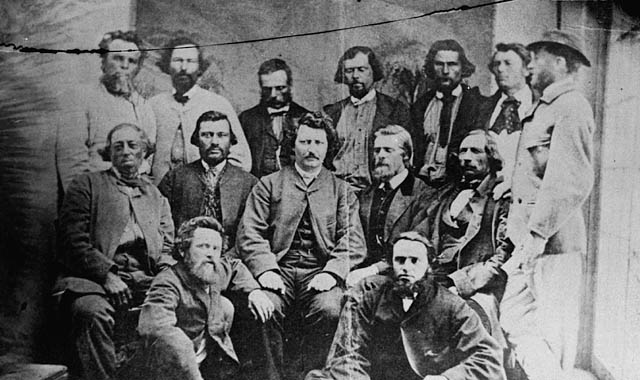

The three early issues that have framed contemporary debates around Québec nationalism were the ‘The Manitoba School Issue’, the ‘Conscription Issue’, and the issue of bilingualism. The Manitoba School Issue was the first serious test placed on the French-English tension after Confederation. It was a test of the right of Manitobans to receive an education in their mother tongue. In 1870 the province was created by the Manitoba Act. The Métis of the Red River Colony had been a key actor in agitating for the creation of the province in order to secure their cultural, religious, and language rights. This had led to the Red River Rebellion and the martyring of Louis Riel as a defender of French rights.

Figure 11-8: “Louis Riel and the Métis Provisional” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AProvisionalMetisGovernment.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

As a consequence, language rights were enshrined in section 23 of the Manitoba Act, whereby anglophones and francophones were guaranteed the use of their language in the legislature or courts. Section 22 established the system of French schools for Catholics and English schools for Protestants. This dual English and French education system was further reinforced through the ‘Act to establish a system of education in the province of Manitoba’ in 1871. However, changing demographics would shift the balance of power away from the French speaking Métis towards English speaking settlers. This was partly due to the migration of the Métis further west and partly due to the Federal immigration policies of European anglophones. In 1875, policies of bilingualism were undermined when ridings constituted by majority anglophones abolished the use of French. Further, in 1876, a key defender of minority rights, the Legislative Council of Manitoba, was abolished to cut expenses. In 1890, the Manitoban government legislated the abolishment of French as an official language. In the same year, two further bills were passed ‘An Act respecting the Department of Education’ and ‘An Act respecting Public Schools’. The first act eliminated the separate French and English sections of the Board of Education, amalgamating them into one Department of Education. The second act eliminated the religious denominated school districts. While it did not outright eliminate French schools, it did eliminate funding for Catholic schools which was the primary provider of French language education. Henceforth, if Catholics wanted to receive a religious education, their schools would have to be privately funded. Further, they would also be paying taxes for the public schools they would not be attending. The financial burden was increased in 1894 by prohibiting municipalities from assisting schools outside of the public system.

Figure 11-9: “Wood Lake School Manitoba 1896” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AWood_Lake_School-1896.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Kempthorne.

During this process, the British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council upheld the Manitoban legislation but also confirmed the power of the federal government to restore school privileges. This posed an important dilemma for French Québec. If they supported the federal government’s power to overturn provincial legislation, they would be protecting French language rights, but they would also be accepting the federal power of disallowance. This became a federal election issue in 1896. The Conservatives proposed remedial legislation for the provision of French education and were supported by Manitoban francophones and the Roman Catholic Church. Meanwhile, the Liberal were in favour of provincial autonomy and were supported by Québec francophones as well as anti-French and anti-Catholic voting blocks. The Liberals prevailed and the federal power of disallowance was not used, although compromises were made. Specifically, the ‘Terms of Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of Manitoba for the Settlement of the School Question’ was passed in 1896, allowing instruction in minority languages, including French. However, the 1916 ‘Thornton Act’ repealed these compromises and prohibited the use of any language other than English in public schools. Much like the impact of the explicit assimilation polices in the 1840s, the exclusion of French language education galvanized resistance and French nationalism.

The second important event contributing to the rise of French nationalism was the ‘conscription issue’ of 1917 created by the ‘Military Service Act’. The act allowed the conscription of all Canadian men between the ages of 20 and 45 for the First World War. Prime Minister Robert Borden believed that conscription was necessary to reinforce the Canadian Expeditionary Force which was being depleted by the attrition of trench warfare. However, the actual impact of the act was relatively minimal in that only 24,132 conscripted men made it to the battlefield versus the 400,000 Canadian men who volunteered. Borden sought to make Conscription a bipartisan effort by proposing a national unity government or coalition government to Liberal leader Sir Wilfred Laurier. Regardless of Laurier’s preferences, he was constrained by opposition from his Québec MPs. Borden then opted to cobble together a Union government with a cabinet composed of 12 Conservatives, 9 Liberals and Independents, and one Labour member. An election was called on the issue and, upon winning, Borden’s Union slate formed government. Importantly, the conscription issue created a serious schism between French and English speaking Canadians. For the most part, English speaking Canadians supported Borden and his conscription policy. Conversely, French speaking Canadians, and every French Speaking MP, opposed conscription. The consequences of Borden’s conscription policy had a lasting legacy on both Canadian politics and French nationalism. In terms of politics, the conscription issue would severely constrain Conservative electability in Québec which in turn greatly impeded their ability to form national government. The resistance to conscription by French speaking Canadians would reinforce Québec nationalism. For many French Canadians, Borden’s appeal to rescue the French in Europe while not defending French rights in Canada was hypocrisy. For some French leaders, like Henri Bourassa, conscription imposed against the express consent of French speakers and all French politicians, was a betrayal of the compact theory of Confederation. Others, like Lionel Groulx, took it further and used the conscription issue to support the narrative that French Canadians had been badly served by the French who had colonized New France, the British who took over from them, and now the Canadian government. From this perspective, French Canadians must seek independence to actualise their self-determination.

Figure 11-10: “Anti-conscription March in Montreal 1917” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AAnti-conscription_parade_at_Victoria_Square.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

The last issue, language rights, bridges both early and contemporary nationalism in Québec. As seen, in the Manitoban school issue, language rights were a major factor in dividing French and English Canadians as it continues to be today. Language rights in Canada were a key element of the Confederation negotiations, subsequently enshrined in the British North America Act. The BNA specifies that Parliament and the Québec National Assembly were to function in both French and English. However, this does not extend to provincial legislatures nor to provincial government services. Language rights were extended under the 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms to all matters pertaining to Parliament as well as enshrining minority language rights. Under section 23 of the Charter, citizens of Canada whose first language is a minority in the province they reside and who received their education in that language, are entitled to have their children educated in the same language, wherever numbers warrant it. This section of the Charter thereby addresses the tensions created by the Manitoban school issue and similar examples in other provinces. This has resulted in several supreme court challenges, asking the court to mandate the provinces to fulfill their constitutional obligations. In 1963, the Liberal government made all federal institutions bilingual. This was legislated in 1969 with the Official Languages Act and updated in 1988. The Official Languages Act applies to governmental institutions and those external institutions that they regulate such as airlines and banks. This allows federal employees to work in their preferred language and for citizens to access government services in their preferred language where significant demand exists. It also created a national framework to promote both official languages. The provinces too have the right to pass legislation regarding language rights, but most often this legislation is restrictive versus empowering. The Manitoban school issue is a case in point as is the Office Québécois de la langue française passed in 1977, which enforces the Charte de la langue française. The Charter requires all provincial legislation to be in French, as well as all administration, business transactions, and education. This legislation was challenged on constitutional grounds by the federal government with the case being heard by the Supreme Court of Canada. The Court struck down Sections 7 through 13 as well as obliging the amendment of Chapter VII. The former declared French the language of the Courts and legislation and the later dealt with the language of teaching. The Language Charter also restricted the educational rights of immigrants, by requiring them to study in French absent a reciprocal provincial agreement. The Courts decisions required the Québec National Assembly to pass remedial legislation to bring their language laws into constitutional alignment. On the other hand, New Brunswick passed legislation in 1969 making the province officially bilingual.

Figure 11-11: “Bilingual Street Sign in Ottawa” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ABilingualstopsign.jpgPermission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Ibagli.

On the whole, language policy in Canada is much contested and much misunderstood. Many assume the Official Language Act means that Canadians ‘should’ speak both languages. In actuality, it is intended to ensure the legal equality of French and English, to protect the language rights of English and French speaking minorities, and to provide a minimum level of government services in both official languages. It should also be noted that while 43% of Québécois are bilingual, the emphasis has shifted in the province from supporting bilingualism to making Québec a French only province. On the other hand, while parts of English Canada have historically adopted anti-French legislation, like in the Manitoba school issue, 72% of Canadians now support official bilingualism.

The three issues discussed above set the context for contemporary debates in Québec nationalism. The Manitoban school issue and the conscription issue both galvanized and legitimated this nationalism. Both issues were seen as examples of an anti-French bias in the country. They were seen as evidence that the interests of English speaking Canadians came first and foremost. They were seen as requiring a nationalist movement to pursue the interests of French speakers and, for some, to pursue a sovereign state. Several factors are at the crux of Québec nationalism. There is both a fear of being overwhelmed by English Canada with French culture increasingly marginalized. There is also a pride in that culture, a need to have its value recognized. The most poignant trigger of Québec nationalism surrounds language rights; the legal equality of French to English, the right to access government services in French as well as English, and the protection of French minority groups to be educated in their mother tongue. For Québec nationalists, language was an important metric of recognition of Canada as a bilingual state and ultimately a metric of respect.

Watch ‘Bilingualism in Canada’:

Watch ‘Speakers Corner: Talking bilingualism in Canada’:

Use the following questions to guide a post to your Learning Activity Discussion Board.

- What is bilingualism?

- The first video takes a legal and academic stand on bilingualism, while the second video takes a more popular understanding of bilingualism

- How do they understand bilingualism differently?

- Are these differences important?

- What bearing, if any, do they have on the issue of Québec nationalism?

Figure 10-12: “Premier Lesage” Source: https://schoolworkhelper.net/quebecs-quiet-revolution-summary-significance/ Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

Modern Québec nationalism emerged during the ‘quiet revolution’, a time of profound social, political, and economic change starting in the 1960s. It was during this time that a disconnect manifested between Québec society and its politics. Society was increasingly industrialized, urban, and progressive. But politically, Québec was more parochial and socially conservative, defined by the Union Nationale party which had managed to maintain power for 16 years and supported by the Catholic Church. The Liberal government of Jean Lesage broke the hold of the Union Nationale party on Québec in 1960. The Lesage Government pushed back against political patronage, adjusted the electoral map to take into account the new urban reality, reformed campaign finance laws, and attempted to balance the budget. There was an explicit policy of francization of education, health services, and the government bureaucracy. The private electricity companies were nationalized, creating one of the largest Crown Corporations in North America, Hydro-Québec. The government also sought to expand it’s role in providing social services. In so doing, the government challenged and ultimately reduced the role of the Catholic Church, leading to a more secularized Québec. The province also began to make international connections, opening foreign missions and butting heads with the federal government over who ‘spoke’ for Canada.

Québec was becoming more assertive in defining and defending its interests and values, at home and abroad. Cumulatively, out of this process, emerged Québec nationalism albeit in two variants. The one variant was represented by the likes of Pierre Elliot Trudeau, who sought a strong federal government that was more inclusive of French speakers as a means to reduce federal-provincial tension. He pushed for the Official Languages Act, the repatriation of the Constitution, and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Trudeau believed these institutional responses would create a bilingual and bicultural state. The other variant embodied separatist political organizations, led by the likes of René Lévesque who was the first leader of the Parti Québécois.

Figure 11-13: “Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau” Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Pierre_Trudeau Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Rob Mieremet / Anefo.

Figure 11-14: “René Lévesque” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ARen%C3%A9_L%C3%A9vesque_BAnQ_P243S1D865.jpgPermission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Harvey Majo.

These separatist movements have sought political emancipation and have brought Québec to the brink of leaving Canada twice. Three major events have defined contemporary Québec nationalism including the 1980 Québec referendum, the problem of Constitutional Patriation, and the Québec referendum of 1995.

The principal actor behind the 1980 Québec Referendum was the Parti Québécois. The PQ was formed by a merger of the Mouvement souveraineté-association and the Ralliement national in 1968. They won the provincial election of 1976 on a political platform that included a promise to hold a referendum on sovereignty association. When the federal Liberals lost power in 1979 to the Progressive Conservatives under Joe Clark, a window opened to hold the referendum. The PCs were not influential in Québec and having only attained a minority government, they were not in a strong position to obstruct the PQs. On December 20th, 1980, the following question was posed to the citizens of Québec:

The Government of Quebec has made public its proposal to negotiate a new agreement with the rest of Canada, based on the equality of nations; this agreement would enable Quebec to acquire the exclusive power to make its laws, levy its taxes and establish relations abroad — in other words, sovereignty — and at the same time to maintain with Canada an economic association including a common currency; any change in political status resulting from these negotiations will only be implemented with popular approval through another referendum; on these terms, do you give the Government of Quebec the mandate to negotiate the proposed agreement between Quebec and Canada?

Unfortunately for the PQs, Clark’s Government fell after 9 months, returning Trudeau and the Liberal’s to power with a majority government and promises of both renewed and more inclusive federalism. The Liberals took 74 out of 75 federal ridings in Québec, giving them a strong platform and mandate to obstruct the PQs separatist intentions. The results of the referendum were a blow to the separatist movement in Québec. There was high turnout for the referendum, nearly 86%, with nearly 60% voting against it. This was a particularly strong rejection given the relatively weak question being asked; it did not ask if Québec should separate from Canada but rather it asked if it should be sovereign but remain in an economic union with Canada and promised any political change would be put to another referendum. However, while the referendum was rejected, this would only be a setback to the separatist movement and the question would be revisited in 1995.

Figure 11-15: “Neighbours Opposing Positions on the 1980 Referendum” Source: https://flic.kr/p/dNd95n Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Caribb.

Before turning to the second referendum in 1995, it is important to look at the patriation of the Constitution in 1982 and its aftermath. The negotiations on the patriation of the Constitution followed closely on the heels of the 1980 referendum. We dealt with the patriation of the Constitution in some detail in module three, so we will restrict the discussion here to the impact on Québec nationalism. The patriation of the Constitution with the inclusion of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was an important part of the Liberal’s response to the 1980 referendum and the rise of Québec nationalism more generally. As mentioned earlier, it was meant to be one of the means to address the concerns of Québec nationalists by building a truly bilingual and bicultural state. Following the referendum, intense federal-provincial negotiations on patriating the constitution took place, but the federal government was initially unable to get the provinces to sign off on their proposal. After both the threat of patriation without the provinces and the subsequent Supreme Court Decision on the legality of such a course of action, the federal government brought the provinces together for one final conference. In the end, all the provinces with the exception of Québec agreed on a deal to move forward with patriation. This exclusion of Québec in the deal to patriate the constitution and the subsequent perception that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was imposed on Québec after patriation, reinvigorated the separatist movement. Two subsequent attempts were made to obtain Québec’s consent to the Constitution and remove this irritant in federal-provincial relations, namely the Meech Lake Accord in 1987 and the Charlottetown Accord in 1992. The Meech Lake Accord was an attempt to amend the Constitution and included two aspects relevant to Québec. First, if passed, it would recognize Québec as a ‘distinct society’. Second, the provinces, including that of Québec, would be given more powers and influence in things like nominating senators or Supreme Court justices and the means by which federally funded social programs are run.

Figure 11-16: “Lucian Bouchard” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bouchardimg229us-signed.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Markbellis.

However, the Meech Lake Accord failed to pass when it was unable to garner the necessary support from the provinces. Importantly, anger in Québec over this failure resulted in Lucien Bouchard, the then Progressive Conservative Minister for the Environment, to lead a mix of both PC and Liberal MPs from Québec to form the Bloc Québécois.

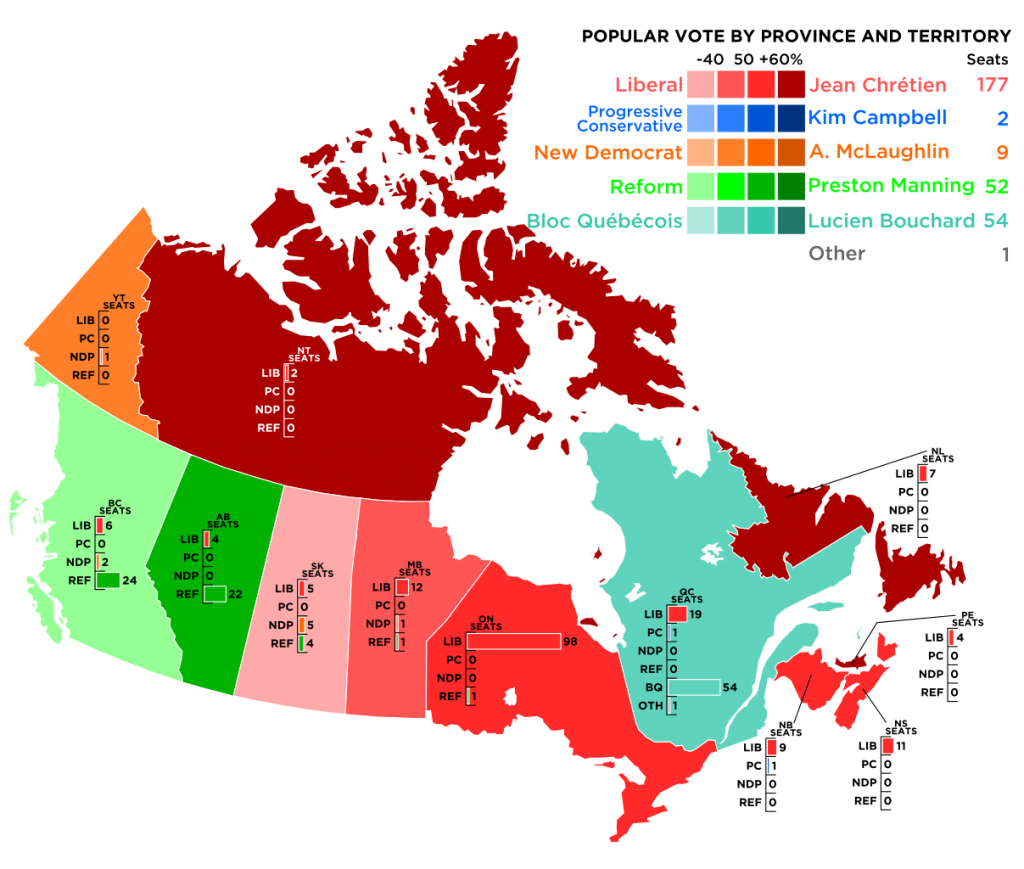

The Charlottetown Accord was a second amend attempt to gain Québec’s consent to the Constitution. In reaction to criticism that the Meech Lake Accord was too opaque, the process of the Charlottetown Accord was built to be transparent with a robust national dialogue. Important to the question of Québec nationalism, the accord would again recognize Québec as a distinct society within Canada. It would delegate more exclusive jurisdiction to the provinces in a number of areas including cultural affairs. It would shift the division of federal-provincial jurisdictional authority and spending power towards the provinces. While the Charlottetown Accord did have the support of the federal government and all the provincial governments, it failed to pass a national referendum. This national referendum was not legally required but was a choice made by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney to make the process more transparent. The failure of both the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords combined with the lack of any further appetite for constitutional reform empowered Québec nationalism. It gained further momentum in the 1993 federal election whereby the Bloc Québécois won 54 seats to become the official opposition and in 1994 when the PQ formed government in Québec.

Figure 11-17: “Canada 1993 Federal Election” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACanada_1993_Federal_Election.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.5 Courtesy of Lokal_Profil.

While English speaking Canada had a case of constitutional fatigue, this was not the case in Québec. The combination of the BQ as official opposition and the PQ forming government in Québec, coupled with both anger and uncertainty over constitutional status, opened the window to another sovereignty referendum in 1995. Again, rather than an outright declaration of independence, the referendum question was intentionally ambiguous to avoid alienating those on the fence over the question of separating from Canada. It read as follows:

Do you agree that Québec should become sovereign, after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new economic and political partnership, within the scope of the Bill respecting the future of Québec and of the agreement signed on 12 June 1995?

Figure 11-18: “‘No’ Sign in the 1995 Québec Referendum” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Non_au_r%C3%A9f%C3%A9rendum_1995.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Zorion.

This question is highly problematic. It is unclear whether voters are being asked to consent to Québec sovereignty or whether they are being asked to approve a normative stance on the relationship between Québec and Canada. It seems to suggest that declaring Québec sovereign was a last resort only to be acted on if Canada didn’t negotiate a new economic and political partnership. Further, the nature of the proposed partnership is left undefined. Finally, the question makes reference to an agreement made between the PQ and another separatist faction, the Action démocratique du Québec, which was later ratified by these two parties and the BQ. This agreement included a declaration of sovereignty which was not expressly evident in the question.

The vote on the referendum was insanely close. People across Canada were glued to their televisions watching the dramatic results of the vote in real time. In the end, 93% of eligible voters participated in the referendum. It was narrowly defeated by 50.6 percent against and 49.4 percent for.

Figure 11-19: “Quebec referendum, 1995 – Results By Riding” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Quebec_referendum,_1995_-_Results_By_Riding.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of DrRandomFactor.

The defeat was blamed by Premier Parizeau on “money and ethnic votes”. And there is some truth to this claim. At the time of the referendum, English speakers and others for whom French was not their native language made up 19% of the population. These groups predominantly lived in large urban centers, like Montreal, and for rural communities these urban centers represented economic and political power. While the referendum was defeated, it neither quelled Québec nationalism nor the threat of another sovereignty attempt. The federal government responded to both the referendum and the threat of future referendums in two ways. First, it sought reconciliation with Québec by: increasing the visibility of French speakers in the government; constitutional proposals to recognize Québec as a distinct society; a statutory veto on any further constitutional reform granted to Québec, Ontario, the West, and Atlantic Canada; devolution of some federal jurisdiction and powers in line with those proposed in the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords; and a public relations campaign set up under the Canadian Unity Information Office which would ultimately lead to its own issues in the Sponsorship Scandal. Second, the government sought clarification on the legality of secession and, if legal, under what conditions. The Supreme Court ruled a unilateral secession was illegal as such change would require changing the constitution. However, it also stated that the federal government and other provinces would be obliged to negotiate with Québec if a clear majority supported independence. In response, the federal government passed the Clarity Act which requires three things before any secession negotiations with a province can take place, namely: a clear referendum question, a clear expression of will within the province, and a clear majority in favour of such negotiations.

Since 1995, threats of another referendum have receded, especially with the ascendency of the Liberals between 2003 and 2012. When Pauline Marois led the PQs back to power in 2012, new speculation on another referendum surfaced. However, the PQs had a minority government and Marois waited until she believed she could win a majority government and therefore have a mandate to call another referendum. In 2014, Marois thought the time was right and called an election. Despite early indications of leading in the polls, the PQ failed to win a majority or even a minority government. Instead, the Liberals under Philippe Couillard won a majority government, and secessionist talks have subsided, for now.

Figure 11-20: “Premiere Pauline Marois” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3APhotographie_officielle_de_Pauline_Marois.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Benoît Levac.

Figure 11-21: “Premier Philippe Couillard” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3APhilippe_Couillard_2014-11-11_E.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Asclepias.

However, the problem of Québec withholding its consent to the Constitution is still there. The perceived slights both by French and English Canada over the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords still exist. The PQ and the BQ still agitate for greater Québécois independence and recognition of the differences between Québec and the rest of Canada. Québec nationalism is alive and support for sovereignty has remained fairly constant. While there are no new referendums foreseen in the near future, it remains an issue that is still very much alive.

Read the Huffington Post Article: The Desire for an Independent Quebec Has Passed Its Peak” huffingtonpost.ca/alain-miville-de-chane/quebec-independence-referendum_b_7576452.html

Use the following questions to guide a post to your Learning Activity Discussion Board.

- What do all successful secessionist movements have in common?

- What is the argument against a 50% +1 vote?

- Why does the article argue Québec’s independence movement is an ethnic project?

- Why does the article argue that independence might have been plausible in the past but is unlikely now or in the future?

- Do you agree or disagree with this assessment?

Québec nationalism is rooted in a debate that has existed since Confederation. At one level, it is a debate about rights and politics and power. At another level, it is about identity, language, and culture. Since Confederation it has manifested in questions of assimilation, education, and political jurisdiction. Early causes of Québec nationalism can be found in the Manitoban School Issue and the issue of conscription during World War One. The hotly contested issue of bilingualism and language rights have been a recurrent theme throughout Canadian history. The Quiet Revolution reshaped Québec’s political, economic, and social structures, emerging more secular and assertive at home and abroad. The call for outright separation from Canada gained ground leading to the referendums in 1980 and 1995. The failure to gain Québec’s consent for the patriation of the Constitution and the two failed attempts at Meech Lake and Charlottetown to subsequently address this have only further stoked nationalist fires in Québec. In many ways, the schism between French and English Canada is the original tension of Confederation. A tension that to this day has not been resolved. However, it should also be noted that this privileging of the issues between French and English Canada has masked other debates. Debates around Canada’s multiculturalism. Debates that address the rights of other minority and marginalized groups in Canada. And perhaps most important, it has masked until very recently the tension between Canada and the Indigenous Peoples who share this land, the topic of our next module.

Review Questions and Answers

The patriation of the Constitution with the inclusion of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was an important part of the Liberal’s response to the 1980 referendum and the rise of Québec nationalism more generally. It was meant to be one of the means to address the concerns of Québec nationalists by building a truly bilingual and bicultural state. Following the referendum, intense federal-provincial negotiations on patriating the constitution took place, but the federal government was initially unable to get the provinces to sign off on their proposal. After both the threat of patriation without the provinces and the subsequent Supreme Court Decision on the legality of such a course of action, the federal government brought the provinces together for one final conference. In the end, all the provinces with the exception of Québec agreed on a deal to move forward with patriation. This exclusion of Québec in the deal to patriate the constitution, the subsequent perception that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was imposed on Québec after patriation, and the failure of both attempts at Constitutional amendments, the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords, reinvigorated the separatist movement in Québec.

Glossary

Bilingualism: Official bilingualism is the term used in Canada to collectively describe the policies, constitutional provisions, and laws that ensure legal equality of English and French in the Parliament and courts of Canada, protect the linguistic rights of English and French-speaking minorities in different provinces, and ensure a level of government services in both languages across Canada.

Bloc Québécois: is a federal political party that was established in 1991 to both support the provincial political party, the Parti Québécois in its sovereigntist agenda as well as to promote Québec’s interests at the national level.

Charlottetown Accord: (1992) was a second amend attempt to gain Québec’s consent to the Constitution. In reaction to criticism that the Meech Lake Accord was too opaque, the process of the Charlottetown Accord was built to be transparent with a robust national dialogue. Important to the question of Québec nationalism, the accord would again recognize Québec as a distinct society within Canada. It would delegate more exclusive jurisdiction to the provinces in a number of areas including cultural affairs. It would shift the division of federal-provincial jurisdictional authority and spending power towards the provinces. While the Charlottetown Accord did have the support of the federal government and all the provincial governments, it failed to pass a national referendum.

Charte de la langue français: was introduced as Bill 101 in 1977 and is the main legislative framework for language policy in Québec. It requires all provincial legislation to be in French, as well as all administration, business transactions, and education. It has been amended six times and each of those times has generated controversy over issues from English based education to the use of English on the websites of Québec based companies.

Clarity Act: was a piece of legislation in 1999 that set out the rules by which the government and Parliament of Canada would react to any future separatist referendum. It concludes that the government will not enter into any negotiations over separation with a province unless the House of Commons determine that (1) the referendum question is “clear” and (2) a “clear” expression of will has been obtained by a “clear” majority of the population.”

Compact theory of confederation: many individuals in Québec subscribe to the compact theory of confederation, which argues that Canada was co-founded by the English and French.

Conscription: or draft, is the compulsory enlistment of people in a national service, most often a military service.

Conscription Issue: an important event that contributed to the rise of French nationalism was the ‘conscription issue’ of 1917 created by the ‘Military Service Act’. The act allowed the conscription of all Canadian men between the ages of 20 and 45 for the First World War.

Disallowance: is a constitutional power over provincial and federal legislation introduced by the British North America Act in 1867 and remains in the patriated Constitution. It was initially a means to ensure legislative compliance with the Constitution. Federally, it allows the Queen in Council to disallow or reserve Federal legislation. It became an issue for Québec in the Manitoba School issue. Québec had to choose to support disallowance of the Manitoba legislation against French Catholic schools but to do so would also recognize more Federal power over the provinces.

Distinct society: a term which has been a focal point of contention between Québec and the rest of the country. It was coined by Lesage in the 1960s but has become a focal point of contention since the 1980 referendum and more importantly the patriation of the Constitution. The term was used in both the failed Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords as a means to recognize Québec’s contribution to Canadian history and culture and thereby facilitate their consenting to the Constitution.

Francization: is the adoption of policies specifically intended to establish the French language as the primary or only language of government, business, and commerce, as well as to discourage the adoption of anglicisms. An important element of francization is barring the requirement of any other language than French as a condition of employment. If a company has more than 50 employees, it is necessary to either acquire a francization certificate from the Québec Office of the French Language or to adopt a francization program in order to eligible for one. Francization policies also include free language courses for immigrants.

Front de libération du Québec (FLQ): In the 1960s, the FLQ was founded to fight Anglo-Saxon imperialism, overthrow the state, and replace it with a Marxist inspired workers’ society. It was subsequently declared a terrorist organization for its violent attacks, in particular the bombing of the Montreal Stock Exchange in 1969 and the October Crisis of 1970.

Lord Durham Report: Between 1791 and 1867, tensions arose over the issue of self-government with rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada in 1837-38. It is during this time that French nationalism began to take shape, with demands for an autonomous state. The Lord Durham Report of 1839, commissioned to investigate the rebellions, recommended joining Upper and Lower Canada and instituting responsible government

Lower Canada: Following the American Revolution, the borders of Lower Canada (Québec) and Upper Canada (Ontario) were established with the Constitutional Act of 1791.

Meech Lake Accord: (1987) was an attempt to amend the Constitution and included two aspects relevant to Québec. First, if passed, it would recognize Québec as a ‘distinct society’. Second, the provinces, including that of Québec, would be given more powers and influence in things like nominating senators or Supreme Court justices and the means by which federally funded social programs are run. However, the Meech Lake Accord failed to pass when it was unable to garner the necessary support from the provinces.

National self-determination: is the right of a people to freely choose their sovereignty and political structures. It is a right recognized by the United Nations and therefore international law. While being recognized under international law, it is notoriously difficult to clearly define its application in practice. Questions arise as to defining the ‘people’ and by what criteria they are able to claim national self-determination.

New France: was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spain in 1763.

Official Languages Act: regulates governmental institutions and those they regulate such as airlines and banks. It also created a national framework to promote both official languages. This allows federal employees to work in their preferred language and for citizens to access government services in their preferred language where significant demand exists.

Parti Québécois: The Parti Québécois is a sovereigntist provincial political party in Quebec.

Province of Canada: was a British colony in North America from 1841-1867. The formation of the Province of Canada was a result of the Lord Durham Report.

Québec Act of 1774: amongst other things, the Quebec Act sought to placate the French Catholics of former New France in case of further instability in the American colonies. In order to do so, the Québec Act removed any reference to the Protestant faith in the oath of allegiance, allowed religious freedom concerning the Catholic faith, and restored the use of French civil law. Importantly, this established the duality of British and French social, political, and economic structures that would set the stage for subsequent tensions between English and French Canada.

Québec referendum of 1995: was the second referendum to ask voters in the Canadian French-speaking province of Quebec whether Quebec should proclaim national sovereignty and become an independent country, with the condition precedent of offering a political and economic agreement to Canada.

Quiet revolution: was a time of profound social, political, and economic change that started in the 1960s. It was during this time that modern Québec nationalism emerged.

Red River Rebellion: was the sequence of events that led up to the 1869 establishment of a provisional government by the Métis leader Louis Riel and his followers at the Red River Colony, in what is now the province of Manitoba. The Métis of the Red River Colony had been a key actor in agitating for the creation of the province in order to secure their cultural, religious, and language rights.

The Manitoba School Issue: was the first serious test placed on the French-English tension after Confederation. It was a test of the right of Manitobans to receive an education in their mother tongue.

Upper Canada: Following the American Revolution, the borders of Lower Canada (Québec) and Upper Canada (Ontario) were established with the Constitutional Act of 1791.

Union Act of 1841: the Act of Union was passed by the British Parliament in July 1840 and proclaimed 10 February 1841. It united the colonies of Upper Canada and Lower Canada under one government, creating the Province of Canada.

Union government: in May 1917, Conservative Prime Minister Borden proposed the formation of a national unity government or coalition government to Liberal leader Sir Wilfrid Laurier in order to enact conscription, and to govern for the remainder of the war.

1980 Québec referendum: was the first referendum in Quebec on the place of Quebec within Canada and whether Quebec should pursue a path toward sovereignty. The referendum was called by Quebec's Parti Québécois (PQ) government, which advocated secession from Canada.

References

“A Fragile Unity ‘Oui’ or ‘Non’.” CBC Learning. 2001. Accessed December 12, 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/history/EPISCONTENTSE1EP17CH1PA1LE.html

Baluja, Tamara and James Bradshaw. “I bilingualism still relevant in Canada?” The Globe and Mail. Updated March 26, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2017. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/is-bilingualism-still-relevant-in-canada/article4365620/

Bélanger, Claude. “Chronology of Quebec Nationalism 1960-1991.” Quebec History. Revised August 23 2000. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/QuebecHistory/chronos/national.htm

Bélanger, Claude. “Jean Lesage and the Quiet Revolution (1960-1966).” Quebec History. Revised August 23, 2000. Accessed December 12, 2017. http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/QuebecHistory/readings/lesage.htm

Bélanger, Claude. “Province of Quebec.” Quebec History. June 5, 2005. Accessed December 12, 2017. http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/encyclopedia/QuebecProvinceof.htm

Bélanger, Claude. “The Language Laws of Quebec.” Quebec History. Revised August 23, 2000. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/readings/langlaws.htm

Bélanger, Claude. “The Quiet Revolution.” Quebec History. Revised August 23, 2000. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/quebechistory/events/quiet.htm

Bélanger, Claude. “1980 Referendum on Soverignty-Association.” Quebec History. August 23, 2000. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/QuebecHistory/stats/1980.htm

“Birth of Manitoba.” Manitobia Digital Resources on Manitoba History. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://manitobia.ca/content/en/themes/bom/4

“Canada: A History of Refuge.” Government of Canada. Modified May 5, 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/canada-role/timeline.html

“Canada to let 300,000 immigrants enter country in 2017.” The Guardian. October 31, 2017. December 12, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/31/canada-immigration-quota-2017

“Catalonia’s bid for independence from Spain explained.” BBC News. December 4, 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-29478415

“chapter C-11. Charter of the French Language” Publications Québec. Updated September 1, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cs/C-11

City News Toronto. “Speakers Corner: Talking bilingualism in Canada.” Youtube. June 28, 2017. Accessed December 13, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AjzOJWThIjo

Colorín Colorado. “Bilingualism in Canada.” Youtube. January 9, 2013. Accessed December 13, 2017.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8QSj0lplDyo

Duboyce, Tim. “Quebec sovereignty talk masks an inconvenient truth.” CBC News. Updated March 15, 2014. Accessed December 12, 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-votes-2014/quebec-sovereignty-talk-masks-an-inconvenient-truth-1.2572933

Flanagan, Tom. “Clarifying the Clarity Act.” The Globe and Mail. Updated July 11, 2011. Accessed December 13, 2017. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/clarifying-the-clarity-act/article586395/

Grenier, Éric. “21.9% of Canadian are immigrants, the highest share in 85 years: StatsCan.” CBC News. Last updated October 27, 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/census-2016-immigration-1.4368970

Johnson, William. “One referendum, three decades of misrepresentation.” The Globe and Mail. Updated August 23, 2012. Accessed December 13, 2017. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/one-referendum-three-decades-of-misrepresentation/article4319787/

Kelly, Amanda. “Fact file: What is Bill 101?” Global News. March 28, 2014. Accessed December 13, 2017. https://globalnews.ca/news/1237519/fact-file-what-is-bill-101/

Leblanc, Daniel. “A brief history of the Bloc Québécois” The Globe and Mail. Updated March 27, 2017. Accessed December 12, 2017. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/a-brief-history-of-the-bloc-quebecois/article4324611/

“Life at Home During the War – Recruitment and Conscription.” Canadian War Museum. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/life-at-home-during-the-war/recruitment-and-conscription/conscription-1917/

McCord Museum. “Confederation: The Creation of Canada.” Youtube. April 23, 2008. Accessed December 13, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hph52hbhYZQ

“Meech Lake Accord.” The Dictionary of Canadian Politics. 2017. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://www.parli.ca/meech-lake-accord/

“Meech Lake.” Heritage Newfoundland & Labrador. 2017. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/politics/wells-government-meech.php

Miville de Chêne, Alain. “The Desire for an Independent Quebec Has Passed Its Peak.” The Huffington Post. June 6, 2015. Accessed December 13, 2017. www.huffingtonpost.ca/alain-miville-de-chane/quebec-independence-referendum_b_7576452.html

“New France: Historical Background in Brief.” Perrault and Mosier… climbing the family tree.” 2014. Accessed December 13, 2017/ http://www.lookbackward.com/perrault/perr1/newfrance/

“Official Languages Act – Annotated version.” Accessed December 13, 2017. https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pubs_pol/hrpubs/tb_a3/olaannot-eng.pdf

Scott, Marian. “Quebec’s conscription crisis divided French and English Canada.” The Great War 1914-1918. July 25, 2014. Accessed December 12, 2017. http://ww1.canada.com/home-front/quebecs-conscription-crisis-divided-french-and-english-canada

“The Manitoba School Questions: 1890 to 1897.” Manitobia Digital Resources on Manitoba History. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://manitobia.ca/content/en/themes/msq

“The Quiet Revolution – The provincial government spearheads revolution in Quebec.” CBC Learning. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/history/EPISCONTENTSE1EP16CH1PA1LE.html

“Towards Confederation.” Library and Archives Canada. May 2, 2005. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/confederation/023001-2500-e.html

“Trivia Quiz – History of Quebec.” Fun Trivia. Accessed December 13, 2017. http://www.funtrivia.com/trivia-quiz/History/History-of-Quebec-I-240232.html

Woods, Allan. “Quebec’s Marois eyeing another sovereignty referendum.” Toronto Star. September 3, 2013. Accessed December 12, 2017. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2013/09/03/quebecs_marois_eyeing_another_sovereignty_referendum.html

Woods, Allan. “Quebec spending millions on diplomatic offices around the world.” Toronto Star. August 3, 2014. Accessed December 12, 2017. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2014/08/03/quebec_spending_millions_on_diplomatic_offices_around_the_world.html

Supplementary Resources

- Jacobs, Jane. The Question of Separatism: Quebec and the Struggle over Sovereignty. 2011 Ed.]. ed. Montréal: Baraka Books, 2011.

- Parizeau, Jacques. An Independent Québec: The Past, the Present and the Future. Montréal: Baraka Books, 2010.

- "Quebec Nationalism and the Struggle for Sovereignty in French Canada." In The National Question: Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Self-Determination in the Twentieth Century, 199. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009