Overview

So far in this course, we have dealt with Canada’s domestic history and politics. In this last module, we turn to Canadian foreign policy and international politics. In module one, we defined the concept of politics as the allocation of scarce resources in a given political community. Or, put more simply, who gets what, when, and how. The competition over the allocation of such resources always carries with it the possibility of conflict because actors competing for such resources may have different or even mutually exclusive interests. This is true in both domestic politics and international politics. However, there is a key difference between the competition for resources at the domestic level and the international level. At the domestic level, the state is tasked with ensuring such competition for resources is kept relatively orderly. The international system on the other hand, is anarchic, meaning there is no over arching authority above the state to do so. This means that in global politics, Canada must compete to achieve its interests amongst other self-interested states in a world of relative insecurity. That is not to say that international politics is lawless or that disorder is the norm. For the most part, most of the time, international politics is orderly, guided by norms, regimes, and institutions that facilitate cooperation. However, in extreme cases, when the interests of states or important non-state actors are at odds, disorder may prevail. This disorder can take a variety of forms, from minor diplomatic disagreements and trade disputes to insurrection, terrorism, conflict, and even world war. It is in this uncertain international environment that states need to craft policy to meet to their interests which are defined by threat and opportunity. This is the realm of foreign policy. In this module, we will define international politics and foreign policy, look at the different models describing Canada’s role in the world, and then detail Canada’s most important international relations.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define foreign policy and international relations

- Differentiate between the three views of Canada in the World

- Describe Canada’s most important international relations

- Read Chapter 12: Canadian Foreign Policy

- Watch ‘The Importance of Developing Your Foreign Policy’ by Stéfanie von Hlatky: https://youtu.be/IG9adB6dne4

- Complete Learning Activity 12.1

- Watch ‘150 Years of Canadian Foreign Policy’: https://youtu.be/1Fsnq0ZUENI

- Complete Learning Activity 12.2

- Watch ‘Will a Biden presidency mean good news for Canada?’

- Complete Learning Activity 12.3

- Alaska Boundary dispute

- Anarchic

- Arctic sovereignty

- Canada-US Free Trade Agreement

- Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement

- Comprehensive Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership

- De facto

- De jure

- Diplomacy

- European Union

- Foreign direct investment

- Foreign Policy

- Imperial satellite

- Institutions

- International law

- International politics

- Legal personality

- Middle power

- Multilateralism

- Norms

- North American Free Trade Agreement

- Northwest Passage

- Oil shocks

- Principal power

- Regimes

- Treaty of Westminster

- UN Charter

- United Nations

- UN Security Council

- 1956 Suez Crisis

- Chapter 12: Canadian Foreign Policy

Learning Material

In domestic politics, actors compete to achieve their interests and can be at odds with each other. We have seen such competition between the provinces and the federal government, between political parties, and between different socio-economic groups. This domestic competition over differing interests is constrained by the constitution and regulated by law with the executive branch, which is tasked with maintaining order. Most disputes are resolved peacefully through the legislative, executive, or judicial branches of government. When serious disorder manifests, the police or even the military can be called in by the state, depending on who has the authority to respond. The Canadian government has patriated the Constitution and adopted the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, setting the broad legal and jurisdictional framework within which actors compete. The government, federally and provincially, draft policies on the economy, on taxation, on education, on health, on the electoral system, on marijuana, et cetera. These policies are drafted in response to perceived opportunities and threats to the state, society, and at times to the more narrowly defined interests of the party in power and their supporters. The government also develops strategies for perceived threats and opportunities at the global level through its foreign policy. The most important actor in determining Canadian foreign policy is the federal government and more specifically the Prime Minister, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and to a lesser degree the cabinet as a whole. However, individual provinces, corporations, and interest groups also have goals that can only be achieved at the global level. These actors not only pursue their own foreign policies but they exert pressure on the federal government to initiate policy or to shape existing policy. As we saw in module 10, Québec has a robust international network, seeking to advance their interests on the global level. Corporations such as Saskatchewan based Cameco, one of the world’s largest uranium producers, has an interest in shaping Canadian legislation and international agreements around the production, refinement, and sale of uranium. The same goes for interest groups and social movements. For example, the Idle No More movement not only tries to influence policy concerning the Indigenous peoples in Canada but is also connected to the global Indigenous movements. However, the focus of this module is Canada and therefore on the state as a foreign policy actor. Therefore, in order to understand Canada’s role in the world, we need to understand what foreign policy is, the narrative of Canada as a foreign policy actor, and Canada’s most important international relations.

Figure 12-2: Source: “Minister of Foreign Affairs Christie Freehand” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AChrystia_Freeland_at_OSCE_-_2017_(38910129611)_(cropped).jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Georges Schneider – Bundesministerium für Europa, Integration und Äußeres.

Figure 12-3: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ADonald_Trump_and_Justin_Trudeau_October_2017.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Joyce N. Boghosian.

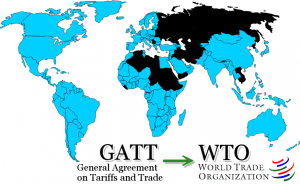

For some, like the authors of our Jackson textbook, foreign policy is the exclusive domain of the state or government. This is a defensible argument as states hold a privileged position in the international system. They act as the gate keeper between the domestic and the international. Domestically, states have a monopoly on the legitimate use of force and use this monopoly to instill a degree of political order. However, it should be noted that the degree of a state’s legitimacy depends on the degree of force required to maintain that order. If a state must use coercion to maintain order, they begin to lose legitimacy and increase the likelihood of insurrection and revolution. Internationally, states have legal personality and a monopoly on the right to bind states to international treaties and agreements. These treaties and agreements form the basis of the international order, as tenuous as that may at times be. Perhaps, the most significant treaty in the contemporary world is the UN Charter, which prohibits states from using force without a UNSC mandate and sets standards of appropriate behaviour at the international level. Other significant agreements include the General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade, which forms the basis of the trade in goods for the World Trade Organization. However, when 69 of the top 100 global economies in 2016 were companies, it is hard to imagine they do not have their own foreign policies. For example, while Canada had the 9th largest economy in 2016, Walmart had the 10th. Walmart certainly has preferences on trade rules and access to global markets. As do resource extraction companies, pharmaceutical companies, technology companies, and companies that offer financial services. Similarly, large non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as Green Peace or Oxfam, try to influence the foreign policies of states, sometimes by directly lobbying the government and at other times indirectly by appealing to the citizenry of state. In the case of Green Peace, they seek to enhance the environmental aspects of state and global agreements. For Oxfam, it is about doing the same to combat poverty and inequality.

Figure 12-4: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/words-wordle-cloud-word-cloud-1752968/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Maialisa.

Regardless, we can define foreign policy as the totality of decisions made by, or on behalf of, an actor, regarding the attainment of goals that can only be achieved at the international level. For states, these goals are most often about economic prosperity or physical security but can also include political influence. Diplomacy is the primary means for states to pursue foreign policy that has been determined by the government: diplomacy between states either bilaterally or multilaterally; diplomacy through institutions like the United Nations and World Trade Organization; diplomacy to negotiate and implement treaties and agreements. However, unlike domestic policy which is structured by constitutions and law, foreign policy operates in an environment where power and interests are determinative.

Figure 12-5: “UN Security Council” Source: https://flic.kr/p/33jCni Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Zack Lee.

For example, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council have veto power, which in many ways puts them above international law. When the US illegally invaded Iraq in 2003, there was no direct consequences. Neither was Russia directly penalized for its annexation of Crimea in 2014. In both cases, when the governments of the US and Russia determined their national interests outweighed the benefits of following international law, they broke that law knowing they could veto any UN Security Council resolution. Yet, most states, most of the time, comply with both international law and the expectations of appropriate behaviour of states on the global stage. Part of this compliance is due to fears of retaliation by other, and often, more powerful states that could harm their political access, economic interests, or even physical security. Another part of this compliance is explained by the increased number and severity of issues which require multilateral responses; think of global warming or refugees. However, part of this compliance is also explained by the fact that political solutions to global problems, economic prosperity, and military security have been greatly enhanced by interstate cooperation. This cooperation has been facilitated by the plethora of international institutions which have created platforms for repeated interaction between states on given issues ranging from trade and security to human rights and the environment. These platforms establish norms, regimes, and even international law, which set out expected standards of behaviour for states and non-state actors. These institutions usually provide systems to monitor compliance with the obligations agreed to and therefore contribute to building trust between actors which in turn promotes further cooperation. When obligations are breached, institutions have varying degrees of enforcement mechanisms to try and coax, shame, or coerce states back into compliance. Therefore, if we take a step back, we can see that foreign policy has to navigate between an orderly world, composed of norms, regimes, and law on one side, and a disorderly world, constituted by power, interests, and the ever-present threat of conflict. It is in this space that Canada, like all other states, compete to achieve their global interests.

Figure 12-6: “Members of the UN” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AUnited_Nations_Members.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Lateiner.

Figure 12-7: “Members of the WTO” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WTO2005.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of By Immanuel Giel.

Figure 12-8: “Members of the OECD” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:OECDMitgliedsstaaten.png#file Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of E Pluribus Anthony.

Figure 12-9: “Regional Organizations” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Regional_Organizations_Map.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Aris Katsaris.

Watch ‘The Importance of Developing Your Foreign Policy’ by Stéfanie von Hlatky:

Use the following questions to guide a post into your Learning Activity Discussion Board.

- Why do we need to develop our own foreign policy?

- What is the perfect world?

- What is the hopeless world?

- Why is it useful to imagine these two worlds?

- How can we take ownership of Canadian foreign policy?

- Why should we take ownership of Canadian foreign policy?

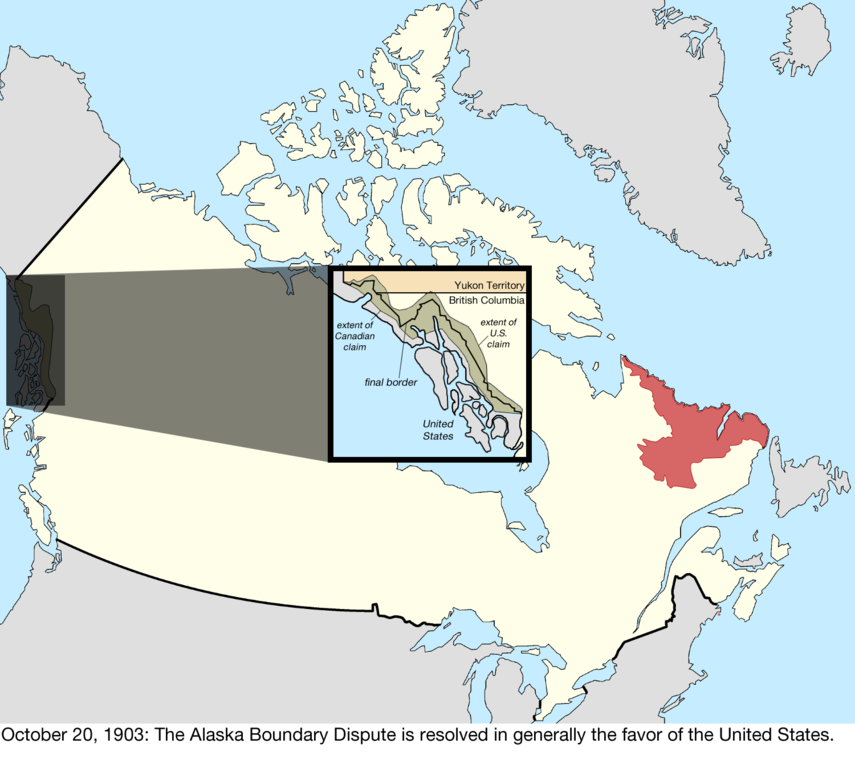

- What issue would you take a position on?

Canada as a foreign policy actor is relatively young. In terms of its internal affairs, Canada became de facto self-governing with Confederation in 1867. As discussed in earlier modules, even this wasn’t completely accurate considering the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council served as Canada’s final court of appeal until 1949. However, in terms of its external affairs, Canada was not de jure independent until the Treaty of Westminster in 1931 and many would argue not de facto independent until World War Two. Prior to 1931, Britain controlled Canada’s external affairs, albeit with input from the Canadian government and the Governor General. For example, John A Macdonald was included on the British negotiation team sent to resolve outstanding issues from the American Civil War, leading to the Treaty of Washington in 1871. However, if British interests and Canadian interests came into conflict, British interests prevailed, most notably seen in the Alaska Boundary dispute.

Figure 12-10: “Alaska Boundary Dispute” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACanada_dispute_change_1903-10-20.png Permission: CC BY 4.0 Courtesy of Golbez.

Figure 12-11: “Premier of Ontario Ferguson, Prime Minister Mackenzie King, Premier of Québec Taschereau at the Dominion-Provincial Conference” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AMackenzie_King_with_Ferguson_and_Taschereau.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

This dispute concerned the establishment of the border between Alaska and British Columbia, an issue that had become pressing due to the Klondike gold rush. An international arbitration committee was formed by the Hay/Herbert Treaty to solve the problem in 1903, consisting of three Americans, two, Canadians, and one Briton. To the chagrin of the Canadian delegates, the British member of the arbitration committee, Lord Alverstone, sided with the Americans effectively undermining Canada’s interests. Britain was more concerned with access to US steel and maintaining American sympathies than with Canada’s claim to the Alaskan panhandle. Moreover, in issues of British colonial, imperial, and military policy, Canada followed the UK. For example, Canada followed the UK into the Boer War of 1899 and later when Britain entered World War One, Canada automatically did as well. Between 1919 and 1931, Canada did begin to seek greater autonomy and as previously mentioned this was formally achieved in 1931 at the Treaty of Westminster.

However, it was not until the end of World War Two that Canada began to formulate a cohesive and robust foreign policy. Since 1945, three main schools of thought have dominated the discussion of Canada’s place in the world. This is an important debate to consider since each school has very different foreign policy prescriptions. The first school of thought defines Canada as a Middle Power: a state that is neither counted amongst the ranks of the Great Powers, but neither is it counted amongst the many small states. Great Powers have global interests, playing a defining role in global politics, economics, and security issues. Small states have localized interests and have few resources to contribute to global concerns. Middle Powers do not play a defining role in global affairs, but they do play a significant role in them. Canada for example played a significant role in both World Wars as determined by resources and manpower. Nearly 61,000 Canadians died in World War One and 43,000 died in World War Two. While Canada’s contribution to World War One was mainly the provision of infantry, in World War Two Canada contributed over one million fulltime military personnel to campaigns on land, sea, and air.

Figure 12-12: “Canadians in a World War One Trench” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canadiens-tranch%C3%A9es.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 12-13: “Canadian Royal Airforce” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3A404_Sqn_RCAF_Beaufighters_Feb_1945.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Flt Lt B.J. Daventry, Royal Air Force official photographer.

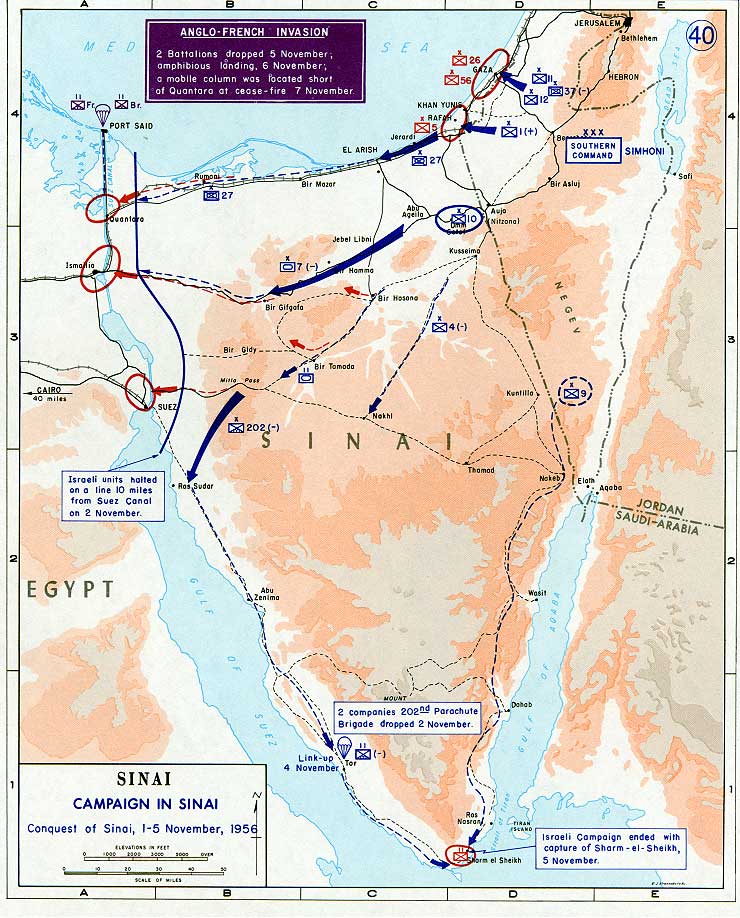

This is a significant number given Canada’s population was only eleven million at the time. However, that is not to say that Canada was a determining power of either conflict, that role would be filled by the Great Powers who were the main antagonists. However, given their significant contribution to World War Two, several Middle Power states like Canada and Australia became very active on the international stage, beginning with the negotiations on the Charter of the United Nations. Once donning the mantle of Middle Power, these states sought an internationalist approach to deterring conflict and encouraging multilateral cooperation. They took leadership roles in policy niches ranging from conflict mitigation to promoting human rights. For those who argue Canada is a Middle Power, they look to the important roles Canada has played in the post war world. The most important role being that of the peacekeeper, with Lester B. Pearson being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in creating the first peacekeeping force in response to the 1956 Suez Crisis.

Figure 12-14: “Map of the Suez Crisis” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1956_Suez_war_-_conquest_of_Sinai.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Canada’s contribution to multilateralism, especially through the UN, is another role that supports the Middle Power argument. In this regard, Canada has played an important role in the law of the sea, the North-South dialogue on international development, human rights promotion, anti-apartheid, environmental policy, chemical warfare, arms trafficking, and child soldiers. Most recently, Canada has led on the issue of maternal health, banning anti-personnel landmines, and perhaps most significantly in establishing the Responsibility to Protect. In all of these examples, Canada did not fundamentally determine the structure of global politics but rather pushed within the given structure to facilitate multilateral approaches to problem solving as well as the formation and adherence to international law.

Figure 12-15: “Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ALester_B._Pearson_1957.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Nobel Foundation, Associated Press.

The heyday of Canada’s Middle Power diplomacy was between 1945 and 1960, often referred to as the Pearsonian internatioanlism. Yet it remains a powerful part of the Canadian narrative and invoked in some shape or form by every government since. From the Middle Power perspective, Canada’s national interest and subsequently its foreign policy should seek to build a more orderly world based on the rule of law. It should seek to constrain the hubris of the powerful states and mitigate the causes of discontent amongst the small states.

However, the Middle Power school of thought has not gone unchallenged. For some, Canada’s internationalism is less a recognition of its occupying a Middle Power role and rather a recognition of its status as an imperial satellite. From this perspective, Canada was first a satellite of the British empire and then later of the American empire. It is argued that this shift from the imperial orbit of the UK to that of the US was not a reflection of changing global circumstances nor increased Canadian influence but rather a reflection of changing global leadership. The UK was one of the great colonial powers and the most dominant of the Canadian state’s three founding nations. It is natural that Canada’s foreign policy would be deeply embedded with that of the UK. However, the 20th century saw the decline of the UK’s global importance and the exponential growth of American influence.

Figure 12-16: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_British_Empire.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of The Red Hat of Pat Ferrick.

This developing relationship between the US and Canada is also natural. Canada and the US share the world’s longest undefended border. They have increasingly interdependent economies, especially since the establishment of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994. In 2014, Canada-US trade constituted a 1.4 trillion-dollar relationship. Canada and the US share in continental defence, especially through the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD) for example as well as broader security commitments though the North Atlantic Treaty Organizations (NATO).

Figure 12-17: “NORAD” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ANorth_American_Aerospace_Defense_Command_logo.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Antonu.

Figure 12-18: “Members of NATO” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:North_Atlantic_Treaty_Organization_(orthographic_projection).svg Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of Addicted04.

American culture has played a big role in Canada while Canada exports many of its top artists and professionals to the US. Even when Canada and the US seem to be at odds politically, for example during the Vietnam War or the 2003 Invasion of Iraq, critics argue that such a foreign policy runs counter to Canadian interests. On the other hand, the governments of Brian Mulroney and Stephen Harper are commonly argued to have been pro-American. It was argued that Canada’s economic prosperity and physical security was best served by aligning itself with America. Perhaps at times, Canada may play the foil to American imperialism; a good cop versus bad cop scenario. But from the perspective of Canada as an imperial dependency, Canada’s national interest and therefore its foreign policy should seek to firmly embed Canada in America’s imperial orbit. It should seek to deepen economic, political, and security arrangements and in so doing will make Canada more secure and prosperous.

The third school of thought, takes the opposite view of the satellite argument: Canada is neither a Middle Power nor an imperial satellite but rather a principal power. This position rests on two arguments. First, Canada has an abundance of natural resources that are increasingly in demand. Moreover, Canada is politically stable and ideologically linked to the core states of the global economy. The attractiveness of these traits was highlighted during the oil shocks of the 1970s. This OPEC manufactured crisis had demonstrated the dependency of developed western countries on states that were ideologically opposed to the US and to the West more generally. This crisis created economic hardship, threatened manufacturing and heavy industry, threatened military preparedness, and created a sense of vulnerability in the West both in government and the public alike.

Figure 12-19: Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/1/18/EthicalOil.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

The attractiveness of Canadian resources has been further accentuated by political instability in resource rich regions like the Middle East and ideological opposition in resource rich states like Venezuela, Iran, and Russia. Events like the Arab Spring have led to further instability in resource rich states like Libya and greater regional instability generated by the Syrian Civil War. Canada has tried to capitalize on its perceived stability in marketing its resources to the world with ‘ethical oil’ being at the forefront of this campaign. In 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper declared Canada to be an emerging energy superpower.

Second, it is argued that the relative decline of American influence in the world opens new spaces for entrepreneurial states like Canada. This is an argument that has recurred several times over the last thirty years. The stagnation of the US economy in the 1970s, its inglorious defeat in Vietnam, and the rise of antipathy to US leadership brought this argument forward. However, it waned in 1989 and the end of the Cold War when the US went from being a super power to a hyper power or even sole global hegemon. The narrative reappeared with the backlash against US leadership after the illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003, strengthened with the financial crisis of 2008, and has emerged again with the election of Donald trump in 2016. A pattern has emerged whereby the decline, or perceived decline, of American power and/or influence is correlated with opportunities for other states to exercise leadership in specific policy areas. In the 1970s, Canada exercised a more independent foreign policy, seeking to build bridges with Cuba, China, and the Soviets. Canada committed resources to multilateral institutions and worked to ameliorate global conflict and poverty. Canada broke with the US over the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and became more assertive in its role as a resource power and in defining its sovereignty in the arctic. However, between 2002 and 2011, Canadian politics was consumed by domestic concerns which deemphasized foreign policy concerns. Such domestic concerns included the Sponsorship Scandal, three minority governments, and the impact of the 2008 global financial crisis.

All three schools of thought can make persuasive arguments as to the merits of their respective understanding of Canadian foreign policy. And for most, if not all, post war governments, there is evidence supporting each school. For example, Middle Power internationalism is almost synonymous with Lester B. Pearson albeit more for his role as External Affairs Minister rather than his role as Prime Minister. However, all subsequent Prime Ministers enacted the Middle Power role with the exception of Stephen Harper. For example, Diefenbaker and Mulroney were highly involved in combatting South African Apartheid; Pierre Trudeau involved Canada in global affairs and sought to build bridges with revisionist states like China and Cuba as well as to foster better North-South dialogue; Chretien and Martin were highly involved in the Anti-Personnel Landmine Ban, the International Criminal Court, and the Responsibility to Protect. Yet, the same can be said of the other two schools of thought. The ‘Canada as a satellite school’ identifies foreign policy that recognizes the significance of the US relationship to Canada. For example, Pearson signed the 1965 Auto Pact; Diefenbaker approved plans that led to NORAD; Pierre Trudeau allowed the US to test cruise missiles in Canada and joined the G7 at the behest of the US President; Mulroney brought Canada into the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA); Chretien joined NATO and the US in the illegal Kosovar War and; Harper made extraordinary commitments to Afghanistan. The ‘Canada as a principal power school’ identifies examples of Canadian global leadership. For example, Pearson’s leadership on Peacekeeping; Diefenbaker’s leadership in the Commonwealth; Pierre Trudeau’s interference in the Cold War conflicts with Vietnam, China, and Cuba; Mulroney’s conflict with the US and the UK over South African apartheid; Chretien’s refusal to join the US in Iraq and; Harper’s rebuke to the US on Arctic sovereignty. So what to make of this? This apparent inconsistency in Canada’s foreign policy reflects the tension between foreign policy orientations of specific governments and the opportunities/threats that governments encounter while in power. There is an inherent tension between identity and interests. While Pearson, Pierre Trudeau, and Chretien might be characterized as having a Middle Power international orientation, they still had to respond to foreign policy issues that required deviation from that orientation or domestic constraints such as a financial crisis. The same goes for all governments. This means that while a government may have preferences and hold beliefs as to what the country’s foreign policy ‘should be’, they also have to respond to global events and craft policy to achieve the national interest in the global environment as ‘it actually is’. And that may require policy that runs counter to such orientations and beliefs.

Watch ‘150 Years of Canadian Foreign Policy’:

Use the following questions to guide a post to your Learning Activity Discussion Board.

- How did World War One foster Canadian nationalism?

- How did World War Two change Canada’s sense of place in the world?

- What is the ‘golden age’ of Canada on the World Stage?

- What have been some of the highlights of Canadian foreign policy?

- What school of thought best captures Canadian foreign policy?

- What role do you think Canada should play in world? Why?

Finally, this module will look at Canada’s most important foreign relations, including states and institutions. By far, Canada’s most important foreign relationship is with the United States, despite some pretty historic enmity between the respective leaders of the two states. For example, the acrimonious relationship between John Diefenbaker and John F Kennedy which began from Kennedy’s inauguration and further devolved over issues of nuclear weapons and Canada joining the Organization of American States. Chretien and George W Bush also had a rocky relationship. On the other hand, Mulroney and Reagan had a very good relationship, as did Justin Trudeau and Obama. Regardless, as John F Kennedy argued, “geography made us neighbours, history made us friends and economics made us partners”. Canada and the US share common security commitments through NATO and NORAD as well as having the world’s longest undefended border. However, probably the most important aspect of the Canada-US relationship is their highly integrated economic relationship, which was worth 1.4 trillion dollars in 2014. The US is Canada’s largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI), worth 386 billion dollars in 2014. Moreover, during this time, Canada played a reciprocal role, providing 311 billion dollars of FDI to the United States.

Figure 12-20: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ATLC_map.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of TheMexicanGentleman.

This economic integration has been most facilitated by the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and its successor NAFTA. The negotiations of the 1988-89 FTA was highly divisive in Canada. The draft of the agreement was agreed to by the Progressive Conservative Government of Brian Mulroney in 1988. The Liberal opposition leader John Turner asked the Liberal controlled Senate to block it. Subsequently, the 1988 election was dominated by debates on the FTA. With the PCs victory, the FTA was signed and came into force Jan 1st, 1989. Opposition to the FTA remained in Canada, specifically around secure access to the American market, as well as claims that Canada had given away too much in the areas of investment, financial services, agriculture, energy, and the service sector. The FTA was subsequently expanded to include Mexico and was renamed NAFTA. There are critics of NAFTA in all three countries and the Trump administration has initiated a renegotiation of NAFTA making its future highly uncertain. While critics in all three countries have aspects of NAFTA they would like to change, a wholesale abandonment of free trade would be highly detrimental to all three economies.

While the Canadian and American economies are highly integrated, they are not equally dependent on one another. As Pierre Trudeau famously said while addressing the Press Club in Washington,

Figure 12-21: “Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3APierre_Trudeau_(1975).jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Rob Mieremet / Anefo.

“Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast, if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt.”

Canada’s population is 10% of the US’ population. The US’ cultural products, like television, music, and movies, have the potential to swamp those produced in Canada. Its policies, both domestic and foreign, impact Canada deeply. What is most irksome to Canadians about this relationship is that the Americans are most often either oblivious to the impact of the US on Canada or simply take Canadian interests for granted. To flip Trudeau’s quote, while the mouse feels every twitch of the elephant, the elephant is often unaware of the mouse even being there. An example of this tension can be seen in the issue of Artic Sovereignty. The declining ice fields in the Arctic have opened the possibility of connecting the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans via the Northwest passage, a passage that Canada claims. This claim is contested by many states but most significantly the US. Canada claims it is an internal waterway while the US claims it is an international waterway. Until 1988, the relationship between Canada and the US regarding the Northwest passage followed a similar pattern: an American ship would traverse the passage without asking for permission from Canada and Canada would hastily put an escort in front of it. In 1988, they agreed to allow US icebreakers access to Arctic waters on a case by case basis. However, the sovereignty issue remains unsettled and the Americans still consider the Northwest passage an international waterway.

Figure 12-22: “Northwest Passage” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Northwest_passage.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

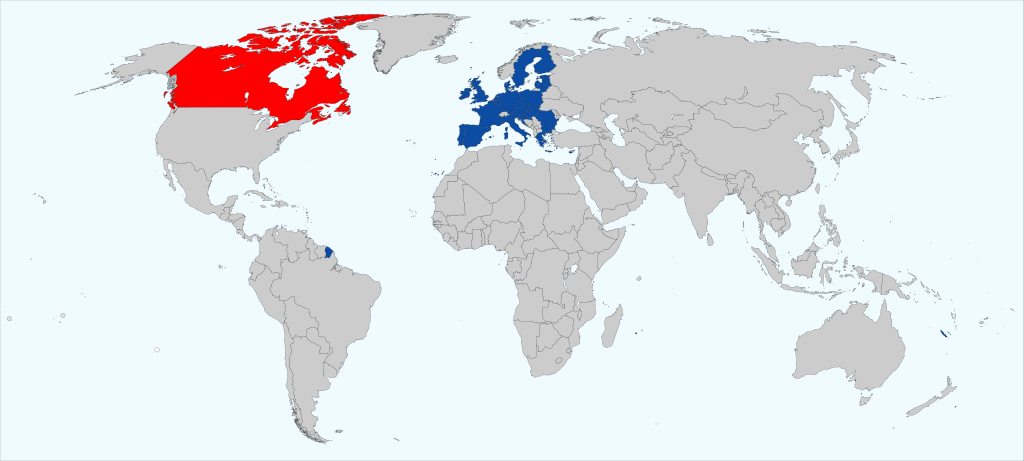

Other important trade relationships include Europe and the Pacific, both of which offer opportunities for Canada to diversify away from its trade reliance on the US. The European Union is an attractive trade partner for any state, and especially for Canada given its historical relationship with the UK and France. The EU, Brexit notwithstanding, constitutes 28 member states which together represent the World’s largest trade area. It has a population of over 500 million people and in 2017 a GDP of almost 27 trillion Canadian dollars, accounting for nearly 30% of nominal global GDP. The EU is Canada’s second largest trade partner, with a particular focus on agricultural and forest products as well as fish. The EU is also Canada’s 2nd largest source of FDI. Canada and the EU have negotiated the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) in 2014 and is awaiting ratification by the EU Member states as well as a decision by the European Court of Justice as to whether CETA’s dispute settlement mechanism is compatible with EU law. If passed, CETA is expected to significantly increase trade in goods and services between Canada and the EU.

Figure 12-23: “CETA-EU Canada” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACETA_-_EU_Canada.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Furfur.

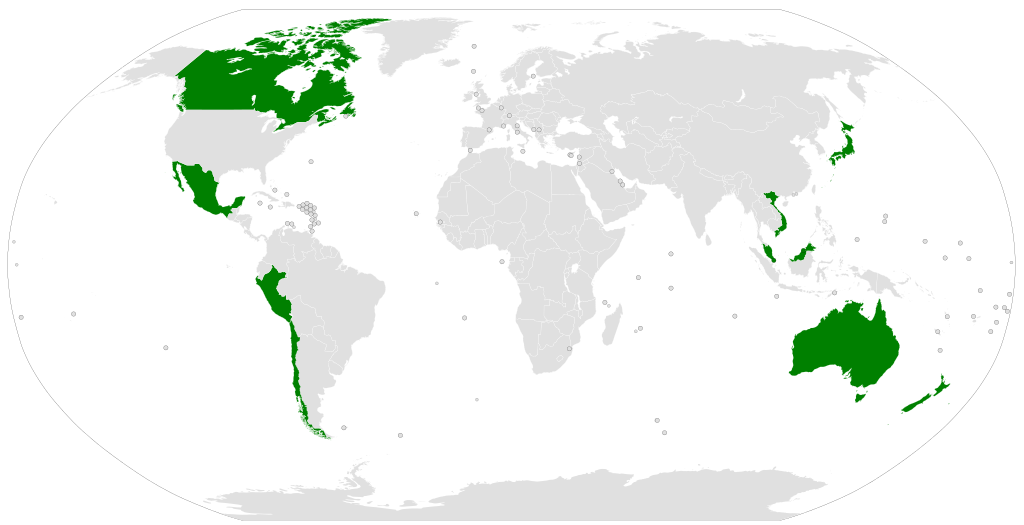

Trade relations with the Pacific Rim is another important growth area. Canada is pursuing two trade relationships in the Pacific Rim. First, is Canada’s trade relationship with China. If you exclude the EU as a whole, China is Canada’s second largest trade partner. Further, Japan and China are Canada’s two fastest growing export markets. Canada and China have begun tentative steps towards a free trade deal which could possibly greatly increase the significance of this economic relationship. While it was expected there would be movement on a trade deal during Trudeau’s visit to China in December 2017, it did not materialize due to the Canadian insistence of the inclusion of ‘progressive values’. These values included separate chapters on the environment, labour standards, and gender equality. The second relationship is the reborn Comprehensive Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP is the successor to the TPP minus the United States and includes Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. Cumulatively, these states represent 1/6th of global trade. If ratified, the CPTPP would create a massive free trade area but important issues remain. Most notably for Canada, there are issues with Canada’s supply management system in dairy and poultry. If forced to abandon these systems, the CPTPP may become as divisive an issue as the FTA and NAFTA. Taken together, the EU and the Pacific Rim offer a potentially significant means to diversify Canada’s economic dependence on the US.

Figure 12-24: “TPP States” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ATPP_members.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of JayCoop.

Canada’s most important institutional relationship has historically been with the United Nations. The UN is the successor organization to the League of Nations (LoN). The LoN was established in the wake of World War One and the UN in the wake of World War Two. The UN was established to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations between states, and to facilitate cooperative solutions to economic, social, and humanitarian problems at the global level. An important means to achieve international peace was the creation of the UN Security Council, composed of five permanent members and 10 rotating non-permanent members. The UNSC is the only body with the authority to issue binding resolutions and to authorize the use of force in maintaining world peace. Canada was one of the original 50 signatory members of the UN. It was highly involved in the negotiation of the institution and worked with other Middle Powers to try and constrain the privilege of the Great Powers. This was a marked change in Canada’s foreign policy orientation, moving from isolationism or at best continentalism, to active internationalism. This shift is best summed up by Pearson who made the following argument while still Minister of External Affairs: “Everything I learned during the war confirmed and strengthened my view as a Canadian that our foreign policy must not be timid or fearful of commitments but activist in accepting international responsibility”. Canada contributed 26,000 troops to the Korean Conflict (1950-1953). Lester B. Pearson served as the president of the UN General Assembly in 1952. In 1956, he and Dag Hammarskjold developed the first peacekeeping force in response to the Suez Crisis, for which Pearson received the 1957 Nobel Peace Prize. As mentioned earlier in the module, Canada was involved in negotiating the terms for new memberships in the UN, has taken leadership roles in a myriad of issues from peacekeeping to the Responsibility to Protect and has been one of the non-permanent members of the security council 6 times. However, under the government of Stephen Harper, Canada failed to win its 7th bid for a non-permanent seat on the UNSC. Many argued this reflected Canada’s reduced commitment to the UN and multilateralism more generally. The election of Justin Trudeau in 2015 has resulted in rhetoric on renewed commitments to the UN, including peacekeeping, but only nominal action so far. The Canadian Delegation to the UN 1945: Pictured from Left to Right C.S. Ritchie, P.E. Renaud, Elizabeth MacCallum, Lucien Moraud, Escott Reid, W.F. Chipman, Lester Pearson, J.H. King, Louis St. Laurent, Rt. Hon. W.L. Mackenzie King, Gordon Graydon, M.J. Coldwell, Cora Casselman, Jean Desy, Hume Wrong, Louis Rasminsky, L.D. Wilgress, M.A. Pope, R. Chaput.

Figure 12-25: “Canadian UN Delegation” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Public_Domain_Image_of_Canadian_UN_delegation.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Nicholas Morant / National Film Board of Canada.

Watch ‘Has the nature of Canada-US relations changed?’:

Use the following questions to guide a post to your Learning Activity Discussion board.

- What is the historical relationship between Canada and the US?

- How did that relationship change under the Trump administration?

- What does the Biden administration appear to mean for that relationship?

- Is Canadian interest in the US more involved than US interest in Canada, and why?

Canada as a state has both an inward and outward face. In both cases, the government needs to react to perceived threats and opportunities through the creation and enactment of policy. Domestically, these policies often take the form of legislation which the state enacts and enforces unless stopped by the judicial branch or deterred by political opposition. In terms of international politics, the government also reacts to perceived threats and opportunities. However, unlike domestic politics, the government must seek to address these threats and opportunities in an anarchic environment amongst other states seeking to do the same. Moreover, this anarchic environment by definition has no overarching authority and therefore is characterized by insecurity and the ever-present threat of conflict. That is not to say international politics is constantly conflictual – it is not. Most states at most times cooperate to achieve their interests. This cooperation is facilitated by norms, regimes, and institutions. However, the threat of conflict means Canada, like all states, must act in an uncertain international environment. There are different views as to how Canada should act on the international stage. Some see Canada as a satellite of first the UK and the later the US. From this perspective, Canadian interests are in alignment with their most influential partner and its foreign policy should reflect this. Others argue that Canada is more akin to a principal power due to it being a stable, ideologically friendly, resource power. From this perspective, Canada has more independence in its foreign policy and can occupy policy spaces created when the Great Powers are in decline. The most common characterization of Canadian foreign policy is that of a Middle Power: a state that is neither counted amongst the ranks of the Great Powers, but neither is it counted amongst the many small states. Middle Powers do not play a defining role in global affairs, but they do play a significant role in them. From this perspective, Canada should adopt an internationalist foreign policy that seeks to constrain the hubris of the Great Powers and mitigate the worst grievances of the small states. All three narratives are supportable and the debate between them is important since they prescribe different foreign policies. However, what is not debatable are Canada’s most important international relations: economically the US, the EU, and the Pacific Rim are Canada’s most important partners. Institutionally, the UN has historically been Canada’s most significant relationship, but one put under significant strain under the Harper government. There has been some rhetoric of renewed internationalism by the current government of Trudeau but so far little action.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Alaska Boundary dispute: The dispute concerned the establishment of the border between Alaska and British Columbia, an issue that had become pressing due to the Klondike gold rush. An international arbitration committee was formed by the Hay/Herbert Treaty to solve the problem in 1903, consisting of three Americans, two, Canadians, and one Briton. To the chagrin of the Canadian delegates, the British member of the arbitration committee, Lord Alverstone, sided with the Americans effectively undermining Canada’s interests.

Anarchic: A system in which there is no central authority.

Arctic sovereignty: Is a key part of Canada’s history and future ¾ 40 percent of the country’s landmass is in its three northern territories, and the country has 162,000 kilometers of Arctic coastline. Sovereignty over the area has become a national priority for Canadians in the 21st century, thanks to growing international interest in the Arctic due to resource development, climate change, control of the Northwest Passage and access to transportation routes.

Canada-US Free Trade Agreement: Was a trade agreement reached by negotiators for Canada and the United States on October 4, 1987 and signed by the leaders of both countries on January 2, 1988. The agreement phased out a wide range of trade restrictions in stages over a ten-year period, and resulted in a great increase in cross-border trade. With the addition of Mexico in 1994, the FTA was superseded by the North America Free Trade Agreement.

Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement: Is a free trade agreement between Canada, the European Union and its Member States. If it enters into force, the treaty will eliminate 98% of the tariffs between Canada and the EU.

Comprehensive Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership: The CPTPP is the successor to the TPP minus the United States and includes Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. Cumulatively, these states represent 1/6th of global trade. If ratified, the CPTPP would create a massive free trade area but important issues remain. Most notably for Canada, there are issues with Canada’s supply management system in dairy and poultry. If forced to abandon these systems, the CPTPP may become as divisive an issue as the FTA and NAFTA.

De facto: Latin for ‘in fact’, describes practices that exist in reality, even if not legally recognized by official laws.

De jure: Latin for ‘in law’, describes practices that are legally recognized whether or not the practices exist in reality.

Diplomacy: Is the primary means for states to pursue foreign policy that has been determined by the government: diplomacy between states either bilaterally or multilaterally; diplomacy through institutions like the United Nations and World Trade Organization; diplomacy to negotiate and implement treaties and agreements.

European Union: Is a political and economic union of 28 European countries. Originally confined to western Europe, the EU undertook a robust expansion into central and eastern Europe in the early 21st century.

Foreign direct investment: Investment made across national borders that has a physical presence or corporate form (such as a branch or plant) and, therefore, a degree of control over how the investment is put to use, as differentiated from indirect investment, also known as portfolio capital or foreign portfolio investment.

Foreign policy: the totality of decisions made by, or on behalf of, an actor, regarding the attainment of goals that can only be achieved at the international level. For states, these goals are most often about economic prosperity or physical security but can also include political influence.

Imperial satellite: a term used to describe a state which is firmly embedded in the orbit of another larger imperial state. It has implications for the foreign policy of the satellite state as they will align their foreign policies with the imperial power as they define their interests as being best served through or in compliance with the larger imperial state.

Institutions: in international politics, an ‘institution’ is sometimes used interchangeably with the term ‘regime’. Within this context, institution can refer to rules, norms, and procedures that are developed by states and international organizations out of their common concerns and are used to organize common activities. Examples of these informal institutions include the Human Rights regime or neo-liberal economics. It can also refer to formal organizations with an established headquarters, staff, and mandate such as the UN or the WTO.

International law: Laws governing the relations among states and other actors active in the international system. International law can be said to originate from norms, rules, customs, and formalized legal principles derived from international organizations/conventions.

International politics: The broad network of relations among states, including the activities of citizens and non-state institutions.

Legal personality: any human being, firm, or government agency that is recognized as having legal rights and obligations, such as having the ability to enter into contracts. In this regard, states have legal personality and a monopoly on the right to bind states to international treaties and agreements.

Middle power: A state that is neither counted amongst the ranks of the Great Powers, but neither is it counted amongst the many small states. Middle Powers do not play a defining role in global affairs, but they do play a significant role in them.

Multilateralism: in international politics, agreement or cooperation between three or more states on any given issue.

Norms: Widely accepted rules that invoke a sense of ‘ought’, which in turn influence how an actor should behave. In international politics, norms refer to a standard of appropriate behaviour for actors with a given identity and can seem to have the force of soft law.

North American Free Trade Agreement: Came into effect, creating one of the world's largest free trade zones and laying the foundations for strong economic growth and rising prosperity for Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

Northwest passage: Is a sea corridor through Canada’s Arctic Archipelago and along the northern coast of North America. European explorers searched in vain for the passage for 300 years, intent on finding a commercially viable western sea route between Europe and Asia.

Oil shocks: The 1973 oil crisis began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries proclaimed an oil embargo. The embargo was targeted at nations perceived as supporting Israel during the Yom Kippur War. By the end of the embargo in March 1974, the price of oil had risen substantially. The embargo caused an oil crisis, or ‘shock’ with many short-term and long-term effects on global politics and the global economy. It was later called the ‘first oil shock’, followed by the 1979 oil crisis, termed the ‘second oil shock’.

Principal power: a state that plays a leadership or dominant role in a specific field. While not a great power with universal interests, principal powers play a defining role in these specific areas. For example, some have argued that Canada is a principal power due to its role in the resource sector.

Regimes: The rules, norms, and procedures that are developed by states and international organizations out of their common concerns and are used to organize common activities.

Treaty of Westminster (1931): Was a British law clarifying the powers of Canada's Parliament and those of the other Commonwealth Dominions. It granted these former colonies full legal freedom except in those areas where they chose to remain subordinate to Britain

UN Charter: Was signed on 26 June 1945, in San Francisco, at the conclusion of the United Nations Conference on International Organization, and came into force on 24 October 1945. The Statute of the International Court of Justice is an integral part of the Charter. The overall purpose of the UN Charter is to: maintain worldwide peace and security; develop relations among nations and; to foster cooperation between nations in order to solve economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian international problems.

United Nations: Founded in 1945 to replace the League of Nations and aimed at facilitating co-operation in international law, international peace and security, and economic and social development, as well as in human rights issues and humanitarian affairs. The UN is currently composed of 193 recognized independent states, and its headquarters is located in New York City on international territory,

UN Security Council: One of the major organs of the United Nations charged with the responsibility for peace and security issues; includes five permanent members with veto power and ten non-permanent members chosen from the General Assembly.

1956 Suez Crisis: Was a military and political confrontation in Egypt that threatened to divide the United States and Great Britain, potentially harming the Western military alliance that had won the Second World War. Lester B. Pearson, who later became prime minister of Canada, won a Nobel Peace Prize for using the world’s first, large-scale United Nations peacekeeping force to de-escalate the situation.

References

Chase, Steven and Nathan Vanderklippe. “Canada-China free-trade talks uncertain, but exploratory discussion continue.” The Globe and Mail. December 4, 2017. Accessed December 17, 2017. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/canada-china-free-trade-talks-uncertain-after-trudeau-li-meeting/article37175979/

Green, Duncan. “The World’s top 100 economies: 31 countries; 69 corporations.” The World Bank. September 20, 2016. Accessed December 17, 2017. https://blogs.worldbank.org/publicsphere/world-s-top-100-economies-31-countries-69-corporations

Ivison, John. “John Ivison: Trudeau can’t seem to export ‘progressive’ trade values. Why keep insiting on it?” National Post. December 7, 2017. Accessed December 17, 2017. http://nationalpost.com/news/politics/john-ivison-trudeau-cant-seem-to-export-progressive-trade-values-why-keep-insisting-on-it

McCarthy, Shawn. “’Ethical oil’ ad sparks war of words between Ottawa, Saudis.” The Globe and Mail. Updated March 26, 2017. Accessed December 17, 2017. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/ethical-oil-ad-sparks-war-of-words-between-ottawa-saudis/article4256682/

Munton, Don. “Canadians and the United Nations at 60+.” United Nations Association in Canada. 1-10. Accessed December 17, 2017. http://unac.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Canadians-and-the-United-Nations-at-60+.pdf

Open Canada. “150 Years of Canadian Foreign Policy.” Youtube. May 15, 2017. Accessed December 19, 2017. https://youtu.be/1Fsnq0ZUENI

Rothwell, Donald. “The Canadian-U.S. Northwest Passage Dispute: A Reassessment.” Cornell International Law Journal. Vol. 26 No. 2. 331-372. 1993. Accessed December 17, 2017. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1309&context=cilj

Skinner, Katie. “Canada’s International Presence – Are we still peacekeepers?” NATO Association of Canada. September 12, 2013. Accessed December 17, 2017. http://natoassociation.ca/canadas-international-presence-are-we-still-peacekeepers/

Smith, Hadfield, and Dunne. Foreign Policy: Theories, Actors, Cases. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Smith, Marie-Danielle. “What you need to know about CETA, Canada’s trade deal with Europe that takes effect today.” National Post. September 21, 2017. Accessed December 17, 2017. http://nationalpost.com/news/politics/canadas-trade-deal-with-europe-takes-effect-today-heres-what-you-need-to-know

Stevenson, Alexandra and Motoko Rich. “Trans-Pacific Trade Partners Are Moving On, Without the U.S.” The New York Times. November 11, 2017. Accessed December 17, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/11/business/trump-tpp-trade.html

Struck, Doug. “Dispute Over NW Passage Revived.” Washington Post. November 6, 2006. Accessed December 17, 2017. www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/11/05/AR2006110500286.html

TEDx Talks. “The Importance of Developing Your Foreign Policy – Stéfanie von Hlatky – TEDxQueensU.” Youtube. March 7, 2017. Accessed December 19, 2017. https://youtu.be/IG9adB6dne4

The National. “Has the nature of Canada-U.S. relations changed?” Youtube. July 3, 2017. Accessed December 19, 2017. https://youtu.be/TcEcE_rtTRU

“U.S. – Canada Economic Relations.” The Embassy of the United States of America, Ottawa, Canada. Accessed December 17, 2017. https://photos.state.gov/libraries/canada/303578/pdfs/us-canada-economic-relations-factsheet.pdf

Walkom, Thomas. “Why Justin Trudea will eventually join the new Trans-Pacific Partnership.” The Star. November 27, 2017. Accessed December 17, 2017. https://www.thestar.com/opinion/star-columnists/2017/11/27/why-justin-trudeau-will-eventually-join-the-new-trans-pacific-partnership.html

Supplementary Resources

- Sjolander, Claire Turenne, and Smith, Heather A. Canada in the World : Internationalism in Canadian Foreign Policy. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Munton, Don. "Whither Internationalism?" International Journal 58, no. 1 (2002): 155-80.

- Bothwell, Robert., Daudelin, Jean. 100 Years of Canadian Foreign Policy. Canada among Nations. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2009.

- Hudson, Valerie M. Foreign Policy Analysis : Classic and Contemporary Theory. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007.

- Nossal, Roussel, and Paquin. International Policy and Politics in Canada. Toronto: Pearson Canada, 2011.