- Explain Global Politics as a function of problem-solving

- Explain the origins and tensions between Realism and Liberalism

- Apply the variants of Realism to global issues

- Apply the variants of Liberalism to global issues

- Compare and contrast the global prescriptions of Realism and Liberalism

Knight, W. A., & Keating, T. F., (2010) “Ch 1 Making Sense of International and Global Politics: Contesting Concepts, Theories, Approaches”, Global Politics: Emerging Networks, Trends and Challenges. Ontario, New York: Oxford University Press Canada.

Antunes, S., & Camisao, I., (2017). Ch 1 Realism. International Relations Theory. McGlinchey, Stephen, Rosie Walters, and Christian Scheinpflug, (Eds). E-International Relations Publishing.

Meiser, J.W., (2017). Ch 2 Liberalism. International Relations Theory. McGlinchey, Stephen, Rosie Walters, and Christian Scheinpflug, (Eds). E-International Relations Publishing

- Liberal Internationalism

- Democratic Peace Theory

- Neo-Liberal Institutionalism

- Classical Realism

- Structural Realism

- Neo-Classical Realism

- Offensive Realism

- Defensive Realism

- Security Dilemma

- System Polarity

Learning Material

In modules 2 and 3, we will set out two very different theoretical approaches to understanding global politics. In module two, we introduce the mainstream, or status quo, approaches to global politics, most notably Liberalism and Realism. These two approaches take the existing international system as a given. This includes an agreement on the existence and meaning of anarchy, the privileged position of the state in the global system, and the potential clash of interests between states. Within this broadly accepted framework, status quo theories seek to understand the global problems we face and how to address them. However, status quo approaches do so without questioning the structure itself.

Figure 2-2: The ministers of foreign affairs and other officials from the P5+1 countries, the European Union and Iran meeting for a Comprehensive agreement on the Iranian nuclear program. John Kerry of the United States, Philip Hammond of the United Kingdom, Sergey Lavrov of Russia, Frank-Walter Steinmeier of Germany, Laurent Fabius of France, Wang Yi of China, Federica Mogherini of the European Union and Javad Zarif of Iran in the “Salle forum” of the Beau-Rivage Palace (Lausanne, Switzerland) on 30 March 2015. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Negotiations_about_Iranian_Nuclear_Program_-_Foreign_Ministers_and_other_Officials_of_P5%2B1_Iran_and_EU_in_Lausanne.jpg#/media/File:Negotiations_about_Iranian_Nuclear_Program_-_Foreign_Ministers_and_other_Officials_of_P5+1_Iran_and_EU_in_Lausanne.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of United States Department of State.

On the other hand, in module three, we will look at the critical approaches to global politics. Critical approaches also identify the contemporary global problems we face, but rather than taking the system as a given, they look to the structure as part of the problem and perhaps part of the solution. Critical theorists question why status quo approaches take concepts like anarchy, state privilege, and conflict as given. In contrast, they unpack these concepts. They argue that in so doing, we may discover transformative or emancipatory means to address global problems in a more meaningful way.

Figure 2-3: Source: https://www.pexels.com/photo/think-outside-of-the-box-6375/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Kaboompics.com.

Back Story

The early work in the study of a truly global politics as a discrete discipline was deeply influenced by the institutional and non-governmental movements of the 19th century. Most formally, we see this in the Concert of Europe, where the Great Powers worked collectively to maintain order in Europe and, albeit less effectively, in their colonial holdings. The Concert of Europe established the idea that states could tame the international system through the strongest actors’ concerted effort. Less formally, we can see the influence of collective action, like the Hague Conferences (1899 and 1907) proposed by Russian Tsar Nicholas II, which sought a means of interstate dispute settlement and the establishment of laws on war and war crimes. There were also functional organizations created to deal with world health issues, international communications, and global labour standards. And there were peace activists, such as the Inter-parliamentary Union founded in 1889, to promote international arbitration and world peace. Together, these movements created momentum and a normative drive to achieve a better, more peaceful, and more equitable world. This momentum was fostered, in part, by NGOs’ which focused on anti-slavery, human rights, and world peace. The academic study of diplomatic history and international law also contributed to the pursuit of global governance.

Figure 2-4: Participants in a women’s peace parade down Fifth Avenue in New York City on August 29, 1914, shortly after the start of World War I. Chief marshal Portia Willis FitzGerald (ca. 1887-?) is on the right. Source: https://flic.kr/p/a61eGg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of The Library of Congress.

However, it was World War One that cemented the systematic study of global politics as a field of enquiry. At the turn of the 20th century, nationalist and ethnic tensions were coming to a boil in Europe. The Great Powers had formed a web of secret alliances that locked them into reciprocal obligations. These tensions and obligations came to a head with the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914. The pursuit of Slavic independence led to the assassination of the Archduke, and the assassination, in turn, put into play the secret alliances like a series of dominoes. That is not to say that the political leaders of Europe dampened the call to war. In fact, many leaders were eagerly anticipating the war to break the impasse created by the nationalist and ethnic tensions. Many still believed Clausewitz’s adage that ‘war is the continuation of politics by other means.’ They saw World War One as a strategic conflict, like those that had come before it. Political and military leaders believed the war would be over relatively quickly when they achieved their national interests. For example, in August of 1914, the German Emperor Wilhelm II blustered that his troops would be home ‘before the autumn leaves fell.’

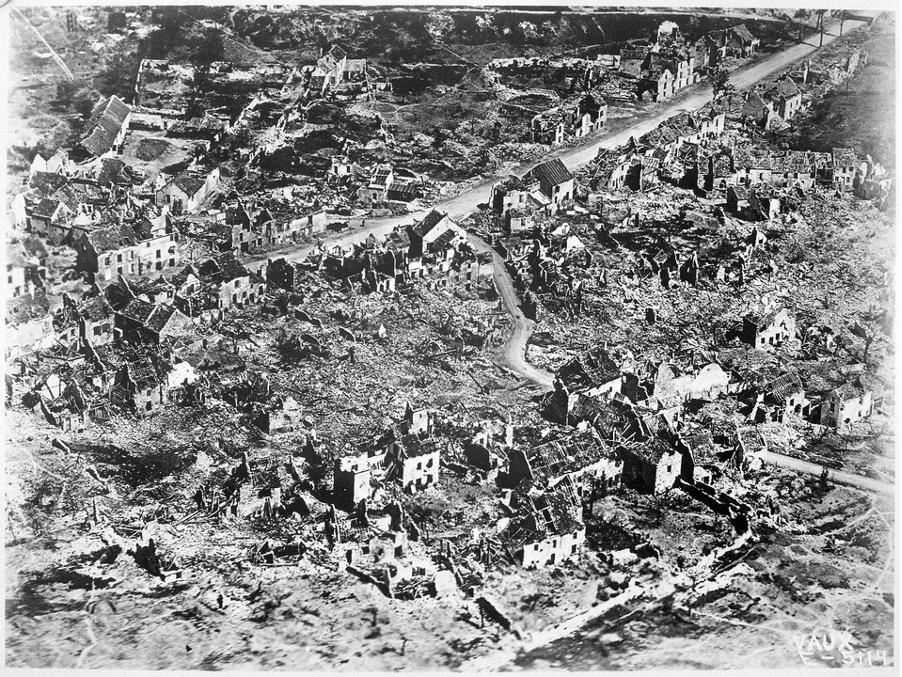

However, by 1919, this was no longer the case. The sheer brutality of mechanized and total war made the cost of state conflict unimaginably high. The machine guns, tanks, aerial combat, chemical weapons, and disease left between 10 and 50 million soldiers and civilians dead and another 20 plus million wounded. This was the catalyst that opened a window of opportunity for statesmen such as Jan C. Smuts of South Africa and Woodrow Wilson of the US to build on the momentum of the 19th-century movements for world peace and global governance. The most formal manifestation of this movement came to fruition during the negotiations for the first international institution of global governance, the League of Nations. This moment in 1919 set up the tension between the two mainstream approaches to global politics, Realism and Liberalism. Though each approach has several variants, they share a set of basic premises. Liberalism argues we can use reason and rationality to achieve a more peaceful and prosperous world. Realism argues this to be idealistic because we live in an anarchical world constituted by self-interested and divergent actors. Therefore, Realists argue we must be prudent, take full consideration of the influence of power, and that perhaps the best we can achieve is global order. These two approaches constitute the dominant approaches to global politics over the last century.

Figure 2-5a: Aerial view of ruins of Vaux, France, 1918, ca. 03/1918 – ca. 11/1918 Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aerial_view_of_ruins_of_Vaux,_France,_1918,_ca._03-1918_-_ca._11-1918_-_NARA_-_512862.tif#/media/File:Aerial_view_of_ruins_of_Vaux,_France,_1918,_ca._03-1918_-_ca._11-1918_-_NARA_-_512862.tif Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Edward Steichen – U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Figure 2-5b: A German trench occupied by British Soldiers near the Albert–Bapaume road at Ovillers-la-Boisselle, July 1916 during the Battle of the Somme. The men are from A Company, 11th Battalion, The Cheshire Regiment. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cheshire_Regiment_trench_Somme_1916.jpg#/media/File:Cheshire_Regiment_trench_Somme_1916.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of John Warwick Brooke.

Of all the approaches to global politics, Liberalism is, in many ways, the biggest political tent. On the one hand, it is closely associated with the movements, organizations, and institutions of the late 19th century and early 20th century that sought to tame global politics. This included the creation of the League of Nations and the functional institutions that sought to promote global health, global trade, and universal human rights. These efforts to transform global politics, and most specifically, the League of Nations, were condemned by many as foolhardy and idealistic. People like E.H. Carr and Hans Morgenthau argued such projects were normative, treating the world as they wanted it to be versus the way the world actually is. The failure of the League of nations to prevent World War Two is used as confirmation of these critiques. The association between these reforms and Liberalism has led some to brand Liberalism more generally as idealistic. But this is unfair, as many variants of Liberalism are far less ‘idealistic.’ They focus on the benefits of commerce, democratic institutions, and individual rights without seeking to transform global politics fundamentally – thus Liberalism is a status quo mainstream theory. With that caveat aside, this module will introduce three variants of Liberalism in global politics: Liberal Internationalism, Democratic Peace Theory, and Neo-Liberal Institutionalism. However, before introducing these variants, we will establish their shared ideological and historical foundations.

Figure 2-6: Reproduction of a painting in the style of Romanticism; Depicted is a theater of war during the French July Revolution (July 28, 1830), in the center the goddess of freedom with the French tricolor in the raised right hand. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/The_Most_Famous_Paintings_of_the_World#/media/File:Eug%C3%A8ne_Delacroix_-_La_libert%C3%A9_guidant_le_peuple.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Eugène Delacroix.

The Enlightenment Ideal: Humans can Improve their Lot

At the broadest level, the global variants of Liberalism share two core assumptions. The first assumption is rooted in an enlightenment ideal, which argues that humans can improve their lot. This is possible because we are born with reason and rationality. We have cured diseases through reason and rationality, created democratic governments, and gone to the moon. Therefore, Liberalism is a narrative of progress as both a possibility and an eventuality. And, from a liberal perspective, there is a lot of room for progress in global politics. Political philosophers, like Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), had long argued that progress was possible, even needed, in global politics. This need for change was highlighted for each of them by the juxtaposition with domestic politics. During the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a powerful momentum towards republicanism, constitutional checks on power, and the privileging of individual rights in Europe’s domestic politics. However, global politics remained, as Kant argued, a “lawless state of savagery.” For Liberal approaches to global politics, this need became a necessity with World War One. The horrors of a sustained, mechanized, and dehumanizing conflict on a global scale left deep material and psychological scars in the body politic. Hence, there was a rise in the prominence of international efforts to pacify global politics, most notably the League of Nations.

Privileging the Individual over Governments and other Power Actors

The second broad assumption is a result of the juxtaposition between domestic and international politics. Progress had been made in domestic politics by privileging individual rights over authoritarian governments’ privileges, like absolute monarchies and dictatorships. In domestic politics, this took the form of securing civil and civic rights, creating normative expectations that legitimate government requires the people’s consent, and enshrining equality before the law. Liberal approaches to global politics also privilege the individual over other power actors. They challenge the state-based world of thick borders and instead recognizes a broader array of actors, including individuals, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), Multinational Corporations (MNCs), and Intergovernmental Organizations (IGOs). They argue borders are more porous, with individuals, groups, companies, and institutions form complex networks that transcend borders. However, the different variants of Liberalism are less consistent in their prescriptions to challenge the state’s privilege and privilege the individual. This is because international politics is very different from domestic politics, creating an ill-fit with the prescriptions that have achieved varying degrees of success in the social-democratic states. International politics is anarchical and composed of sovereign states. So who is the ‘individual’ that liberal approaches are trying to privilege? Is it the state who represents the people? Or is it the individual within the state? If it is the latter, by what legitimate means can we interfere in sovereign states’ domestic affairs? In the absence of an over-arching authority, how can power be checked? How can order and justice be defined, legitimated, implemented, and maintained? These are questions that plague Liberal approaches to global politics. But from a Liberal perspective, this is neither surprising nor problematic. This is a search for progress, and while the goal is known, the means are not.

Three Variants of Liberalism in Global Politics

There are a wide variety of Liberal variants in global politics. We are going to focus on three dominant variants, each with their own implications for global politics: Liberal Internationalism, Democratic Peace Theory, and Neo-Liberal Institutionalism.

Liberal Internationalism

Liberal Internationalism, as an approach to global politics, has waxed and waned over time. It is rooted in the political philosophy of the 18th and 19th centuries. It is most closely associated with the idealism that emerged at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century. Liberal Internationalism believes there is a natural harmony of interests between all people: that we all want lives of security, prosperity, and meaning; that we all want our children to be better off than we are. This harmony of interests is thwarted and perverted by a system that pits one group against another to the benefit of elites. For example, while the political and economic elites may benefit from war, does the same hold true for the people dying on the front lines? For the families who have to do without in order to feed the war machine? From the perspective of Liberal Internationalism, this is as true today as it was in 1914 or 1939. In 2019, the US military budget was 732 billion dollars. At the same time, the US has a very weak social welfare system and a deficit that has exceeded a trillion dollars in 2020. Moreover, the US, which has few direct threats on its borders, has only been at peace for 17 of its 245-year existence. How do we explain this? A Liberal Internationalist might argue that the US military complex is supported by political and economic elites who directly benefit from this spending or indirectly benefit from political patronage systems. They might argue that the system is maintained by a discourse that justifies American exceptionalism and its role as the defender of democracy. But that narrative is created and maintained by the elites to the detriment of the people.

Figure 2-7: “War 2” by Carlos Latuff Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:War2.png#/media/File:War2.png Permission: Free Use. Courtesy of Carlos Latuff.

So what is the solution? Early Liberal Internationalism prescribed two mechanisms to facilitate the natural harmony of interests between all people: commerce and law. It is argued that commerce and law, working in tandem, can tame the ‘lawless state of savagery.’

In terms of commerce, free trade is important for two reasons. First, free trade increases interdependence between states. This, in turn, lessens the benefit and increases the cost of war. Second, free trade thins borders between states, facilitating relationships between people and lessening the distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them,’ which in turn makes it harder to identify ‘them’ as an enemy. Taken together, Liberal Internationalism suggests that the more we trade, the more we come to depend on each other, the more we come to know each other, the less likely we are to support going to war with each other.

In terms of the law, Liberal Internationalism argues for the importance of soft international law. They recognize there is no sovereign to enforce international law. But they do argue that norms, regimes, and legal agreements have force. These legal instruments provide a means to negotiate agreements, regulate international conduct, and set standards of behaviour. Moreover, these legal instruments work best when embedded in formal institutions that regularize contact between states, formalize dispute settlement, and create an expectation that conflict should be resolved peacefully. An important example of this is the League of Nations, which created a universal body to solve global problems, most notably war. War was to be abolished through the idea of collective security, an agreement whereby all member states both renounce the use of war as a legitimate tool of statecraft and agree to collectively defend any member against the aggressive action of any other member.

Figure 2-8: Salle de la Reformation. The official opening of the League of Nations, 1920. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:No-nb_bldsa_5c006.jpg#/media/File:No-nb_bldsa_5c006.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of A. Frankl.

While early Liberal Internationalism was associated with and tarnished by the early 20th century’s idealism, it came back into vogue after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. As the Cold War rivalry between the US and the USSR came to an end, tensions within and between states erupted with horrendous consequences. For example, in 1994, the Rwanda Genocide was responsible for over 800,00 people killed in 100 days, or the Srebrenica massacre in 1995, where Serbian forces executed 7,000 Bosniak men and boys. In light of these trajedies, and in the absence of Cold War constraints, there was a renewed call for progressive change in global politics. This, in turn, renewed interest in Liberal Internationalism and led to the adoption of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). R2P was adopted in 2005 by UN member states and stipulated that if a state was unwilling or unable to protect its citizens from gross human rights abuses, then the international community not only has a right but an obligation to intervene. R2P is potentially transformative, in that states are no longer absolutely sovereign but rather conditionally sovereign. However, with the events of 9/11 and the subsequent Global War on Terror, Liberal Internationalism has once again waned. Yet, it has not disappeared. Liberal Internationalism is a powerful idea. It argues we can exert agency, identify solutions to problems, and achieve progress in global politics.

Figure 2-9: The Nyamata Memorial Site, Rwanda. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nyamata_Memorial_Site_13.jpg#/media/File:Nyamata_Memorial_Site_13.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of I. Inisheer.

Importance and Impact

Liberal internationalism typically sees a surge of interest following global tragedies such as large scale wars or genocide. These events galvanize a belief in, and efforts towards, ensuring such tragedies never happen again. Liberal Internationalism provides a means to do this by recognizing aa natural harmony of interests between people. By focusing on this harmony of interests and using our inherent reason and rationality, peace and prosperity is possible. However, achieving such peace and prosperity requires checking the privilege of the state and instead privileging individuals. Liberal Internationalism suggests this is possible through the free trade, international institutions, and international law.

World War One and the Rwandan Genocide are both examples of immense tragedies that were so unsettling that they provided support and momentum for the prescriptions of Liberal Internationalism.

Democratic Peace Theory

The Democratic Peace Theory (DPT) argues that democratic states do not go to war with each other. It is an offshoot of Kant’s 1795 Project for a Perpetual Peace. Kant argued that a zone of peace was possible if constituted by republican governments. It is important to note that a ‘republican government’ is very distinct from the Republican Party in the United States – rather Kant was referring to constitutionally derived representative democracies. Kant’s proposition was popularized in contemporary International Relations Theory by Michael Doyle in the 1980s. Doyle argued that Kant’s zone of peace was already a reality. The most important ‘zone of peace’ is the European Union, which transformed from the horror of two world wars to a political, economic, and social union of 27 member states. In the study of global politics, DPT is as close as we come to a scientific law. However, the explanation as to why this is true is less clear. One argument is that the political institutions in democracies make war more difficult. The political leadership of democratic states must navigate a system of checks and balances that can slow the rush to war. Further, the institutional obstacles to war allow both sides of a conflict to find other, more peaceful solutions. Another argument is that in a democracy, the government will have to defend its decision to go to war and the costs involved, both materially and the human cost to soldiers and their families. Finally, some argue that DPT holds true because of normative expectations. They note that democracies share cultural norms on the importance of solving conflicts peacefully and through institutional arrangements. Citizens of each state hold their political leadership to these normative expectations. In practice, DPT has played an important role in many states’ contemporary foreign policies. Many social democratic states and international organizations provide considerable resources for fledgling democracies in Africa, South East Asia, and more historically, in Latin America. This can be direct bi-lateral funding to states or indirect funding through NGO and IGO democracy promotion projects. Perhaps most notably, DPT was used by the US following 9/11to legitimate its invasion of Iraq and its broader engagement in the Middle East. That doesn’t mean that supporting democracies is altruistic. These policies are undertaken because advanced capitalistic economies believe that democratic states create regional stability.

Importance and Impact

While there is some debate over the validity of DPT claims, especially on the definition of ‘democracy’ and the causal mechanisms behind them, the DPT is a close as we come to a ‘golden rule’ in global politics. Yet, the Iraq war highlights an important but less discussed aspect of DPT. While it is exceedingly rare that a democratic state goes to war with another democratic state, it is not uncommon for a democratic state to go to war with a non-democratic state. As noted earlier, the US, which has self-proclaimed itself as the defender of democracy, has only known 17 years of peace. This suggests that while Kant’s zone of peace is possible, it would require a very bloody path to get there.

Figure 2-10: Photo of a billboard in Times Square from 2004 that was part of projectbillboard. Source: https://flic.kr/p/2FKq Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Camille King.

Neo-Liberal Institutionalism

With the League of Nations’ failure to stop World War Two, Liberalism was put on the defensive, and it remained there until the 1970s. From 1939 to the 1970s, Realism was the dominant theory of global politics, something we will discuss in the next section. But in order to understand Neo-Liberal Institutionalism, it is essential to understand the context in which it emerged. World War Two had validated a much less optimistic view of global politics – and how could it not? The world had just witnessed the brutality of total and mechanized war, along with the atrocities of the Holocaust and the use of atomic weapons. Then there was the Cold War, where the US and the USSR, two states armed with enough nuclear weapons to destroy the world many times over, squared off around the globe. People perceived the world as a dangerous place, with dangerous actors. However, despite this bleak view of the world, many noticed a trend – that in most places at most times, cooperation was the dominant logic of global politics. Keohane and Nye suggested in 1973 this is due to complex interdependence. Complex interdependence suggests that the world is a more complicated place than most people realize. States are not monolithic, but instead, a variety of actors are involved: different political parties, different government ministries, different social movements, different regional identities. Beyond government, NGOs, MNCs, IGOs, all influenced the form and function of global politics. They did so by creating formal and informal networks that transcend national borders. Moreover, the prevalence of cooperation due to complex interdependence suggests that states are interested in more than just physical security. Rather both state and non-state actors have wider interests that include prosperity, justice, and dealing with global issues. As research into Neo-Liberal Institutionalism developed, they noted that cooperation is facilitated by engaged and continuous interaction, especially through formal institutions. That as actors interact, the distinction between ‘self’ and ‘other’ is lessened, trust is built, and actors begin to focus on absolute versus relative gains. This last argument is important. Suppose, as Realists argue, security is the dominant concern in an anarchical system. In that case, cooperation is difficult as actors worry about relative gains: if an actor gains more than you, they become more powerful than you and become a greater threat. However, if security is but one of many concerns, actors can choose when to focus on security and when to focus on other shared interests. If security is the main concern, then relative gains will be privileged. If other interests are the focus, then actors may choose absolute gains. For example, if the trade partner is not seen as a threat in a trade deal, and both actors will benefit in absolute terms, relative gains are not important. The strength of Neo-Liberal Institutionalism is that it accepts the Realist view of global politics – the state as a privileged and self-interested actor operating in an anarchical system. Yet it still demonstrates that cooperation is not only possible but more prevalent than a Realist would predict. Further, Neo-Liberal Institutionalism demonstrates the potential benefits of formal and informal institutions in facilitating cooperation.

Figure 2-11: United Nations General Assembly hall in New York City. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:UN_General_Assembly_hall.jpg#/media/File:UN_General_Assembly_hall.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Patrick Gruban.

There are three main variants of Realism in global politics: Classical Realism, Structural Realism, and Neo-Classical Realism. However, before introducing these variants, we are going to establish the shared foundation that they rest upon. At the broadest level, Realism shares four core assumptions.

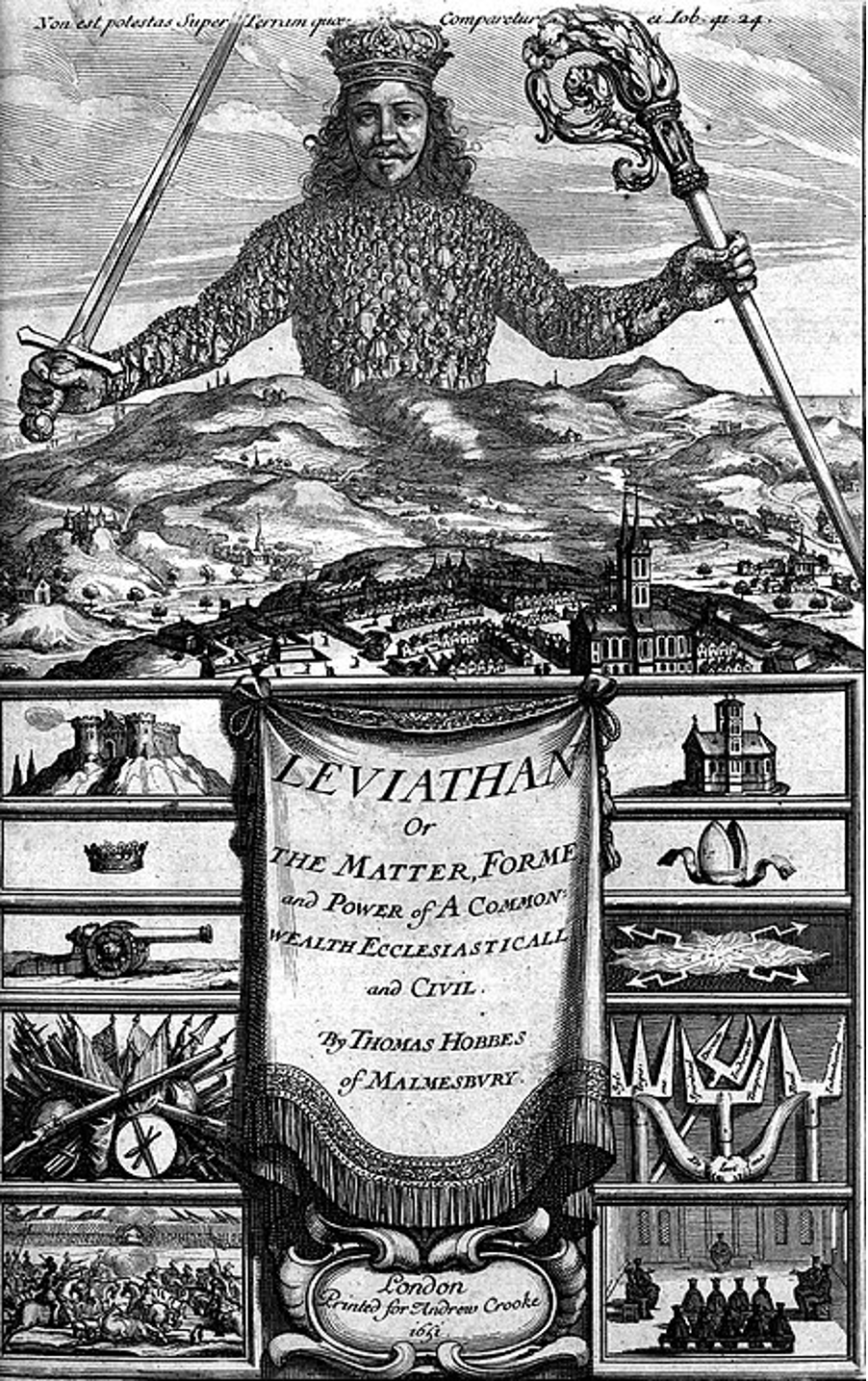

Privileging the Collective or State over the Individual

First, humans organize in groups to attain security and prosperity. Without the group, humans would not be able to rise above basic subsistence. Since the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, the dominant group, or collective actor, is the state. The state is a privileged actor in global politics in that it has a monopoly over the use of violence against domestic and international threats. Domestically, the state may use violence to create and maintain order within its borders. Internationally, citizens expect the state to protect those borders from external threats. Before 1919, war was a legitimate tool of statecraft. However, in 1919, the League of Nations outlawed the use of force as a legitimate foreign policy tool except in the case of self-defence. In 1945, the Charter of the United Nations reaffirmed this law. However, a brief look at modern history would suggest this law has not been honoured in practice.

Figure 2-12: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leviathan_by_Thomas_Hobbes.jpg#/media/File:Leviathan_by_Thomas_Hobbes.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

People and Groups act out of Self-Interest

Second, human behaviour is driven by egoism both as individuals and when acting in groups. That does not mean altruism is impossible, nor even that it is unlikely. Realists recognize that altruism is a possibility – every day, there are stories of people sacrificing their own interests for others. But these are the exceptions that prove the rule. Realists recognize that we cannot depend on altruism since ‘inhumanity is just humanity under pressure.’ Therefore, as individuals, we need to be prepared for the likelihood that people will act on self-interest. For example, if we are bargaining in a business transaction or trying to make rational choices in our lives, the default position is egoism. Acting on behalf of the group raises the stakes, as a mistake will potentially harm the decision maker and those in whose name the decision-maker is acting. Therefore, for Realists, the practice of global politics must be driven by an ethics of prudence.

Figure 2-13: Source: https://flic.kr/p/7Lgg7z Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Michelle Souliere.

Resources and Power Determine Political Outcomes

Third, power is the ultimate determinant of political outcomes. Once humans advanced past the simple hunter-gatherer and subsistence level, society is defined by inequality in resources and power. These inequalities create tensions between groups. Those people/groups who have less caste a covetous eye on those who have more. Those people/groups who have more are wary of those who have less because of those covetous glances. The consequence of this inequality is the need to protect what you have against others. For individuals, this might mean house alarms, private security, or some kind of self-defence. For a state, this means security forces and a strong military – in other words, hard power.

Figure 2-14: Mushroom cloud of ‘Gadget’ over Trinity, seconds after detonation. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trinity_Detonation_T%26B.jpg#/media/File:Trinity_Detonation_T&B.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of United States Department of Energy.

There is no Overarching Authority

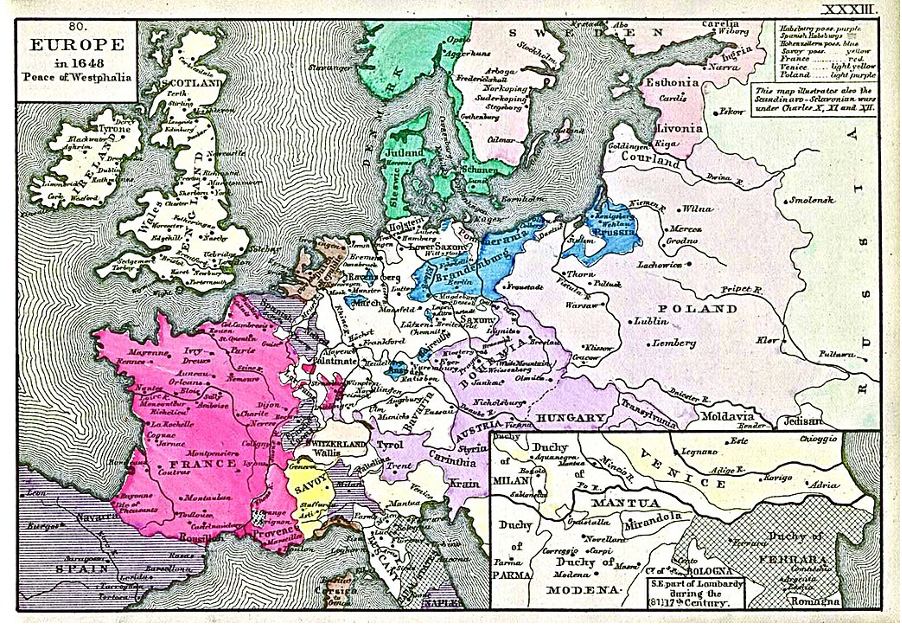

Fourth, the contemporary international system is anarchical. Given the historical context of the 15th-century religious wars and the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, the sovereign state has emerged as the largest functional form of group organization. Since these states are sovereign, the international system is anarchical in that overarching authority is absent. Realists do not argue the international system has to be anarchical – we could have a world empire or a world government. A world empire or government would constitute an overarching authority above states. But this is not the system we have.

Figure 2-15: Europe in 1648 (the Peace of Westphalia after the Thirty Years’ War). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Europe_in_1648_(Peace_of_Westphalia).jpg#/media/File:Europe_in_1648_(Peace_of_Westphalia).jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Robert H. Labberton – University of Texas Library.

Key Takeaways

Realists combine these four elements into their world view. They see sovereign and egoistic states interacting under the condition of anarchy. This necessitates the privileging of self-help, which requires power maximization. Further, they argue that this is not a doctrine of war or coercion. Instead, they argue this is a doctrine of prudence. Realists believe that peace and justice are possible. But the primary form of justice is order. Any higher form of justice is impossible without order. Peace is also possible, but only if states recognize that differentials in power define their interests. Or, as Thucydides argues, ‘the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.’ If all states act according to their place in the system, peace is scientifically predictable and, by extension, achievable.

Three Variants of Realism in Global Politics

There are three main variants of Realism, each with their own implications for global politics: Classical Realism, Structural Realism, and Neo-Classical Realism.

Classical Realism

Classical Realism dominated the study of Global Politics until the 1970s. It is grounded in the work of E.H. Carr and, more specifically, Hans J Morgenthau and his book Politics Among Nations. These authors fought against what they saw as the ‘utopian thinking’ they saw taking root following World War One, or what we discussed as idealism in the last section. They believed that such idealism was not only wrong but that it was dangerous. They argued the utopians or idealists seek to make the world how they wanted it to be: a world constituted by generally good people, seeking cooperative means to achieve a peaceful world. But they argued that this misunderstands the world as it is: a world constituted by egoistic actors, with conflicting interests, that have no compunction against using force to achieve these interests. By mistaking the former for the latter, Classical Realists argue that idealism will lead to conflict and great harm. A view they believe validated by World War Two, the Holocaust, and the existential threat of nuclear annihilation in the Cold War. The correct course of action, according to Classical Realists, is to understand the world through history and diplomacy. They draw on Thucydides, Hobbes, Machiavelli, and Clausewitz, to establish their bona fides. These establish that egoism and self-interest, under the condition of anarchy, make the world a dangerous place. You cannot trust allies or institutions to protect your interests, and you certainly cannot trust the goodness of human nature. You must rely on self-help. From Thucydides’ ‘Melian Debate’ to Clausewitz’s adage that ‘war is the continuation of politics by other means,’ Classical Realists establish a timelessness to their world view. With this world view in mind, Classical Realists argue state leaders must not act on morality, ideology, or parochial ideas of nationalism. To do so will only lead to pointless conflict that does not help them achieve the national interest. Rather, all state leaders can understand and act upon global politics by realizing a simple truth – in global politics, the national interest is defined in terms of power. By defining the national interest in terms of power, all states, in all places, at all times, will act in the same way. To do anything less, in a dangerous world, poses an existential threat – a lesson derived from Thucydides’ Melian Debate, set in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC). This is the story of the island of Melos, strategically situated between the powerful and warring Greek city-states of Athens and Sparta. The Athenians insisted the Melians submit to Athens because of the geostrategic importance of Melos or face destruction. The Melians pled their case, arguing they posed no threat to Athens and insisted on their right to remain independent. The Athenians followed through on their threat: they killed the men of military age, enslaved the women and children, and occupied Melos. From this comes the paraphrased quote: the strong do what they want, and the weak do what they must. This is a crucial argument for Classical Realism, that power determines what states should or should not do – not morality, ethics, or ideology. Every state in Athens’ position should do what Athens did – to do anything less would be to put themselves at risk for the sake of morality. Every state in Melos’s position should realize they must submit to the more substantial power or risk destruction. On a more positive note, Classical Realism posits peace is possible. If we understand the national interest as defined in terms of power, global politics becomes predictable, even scientific. Moreover, Classical Realism argues that peace is therefore also scientific. Peace is established through order. And order is established through a balance of power. Essentially, since all states are possible threats, the rise of one state should be checked by other states. They can do so through internal balancing by increasing their own hard power – military forces, weapons, and lesser degree economic resources. However, this is usually difficult in the short term, and external balancing is necessary – creating coalitions of states to oppose the rise of threats or hegemons.

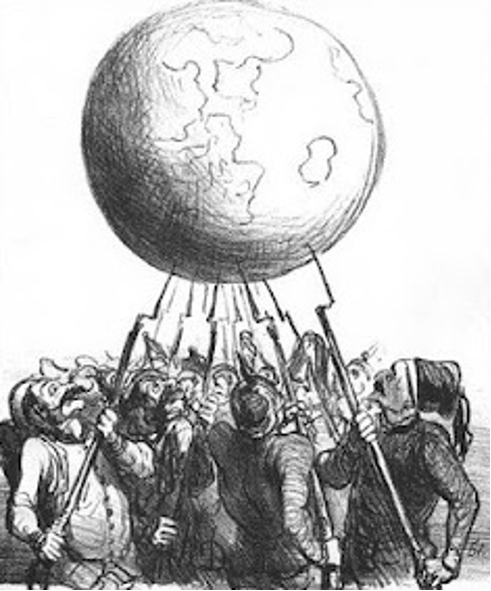

Figure 2-16: 1866 cartoon by Daumier, L’Equilibre Européen, representing the balance of power as soldiers of different nations teeter the earth on bayonets Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BalanceOfPower_(cropped).jpg#/media/File:BalanceOfPower_(cropped).jpg Permission: Public Domain.

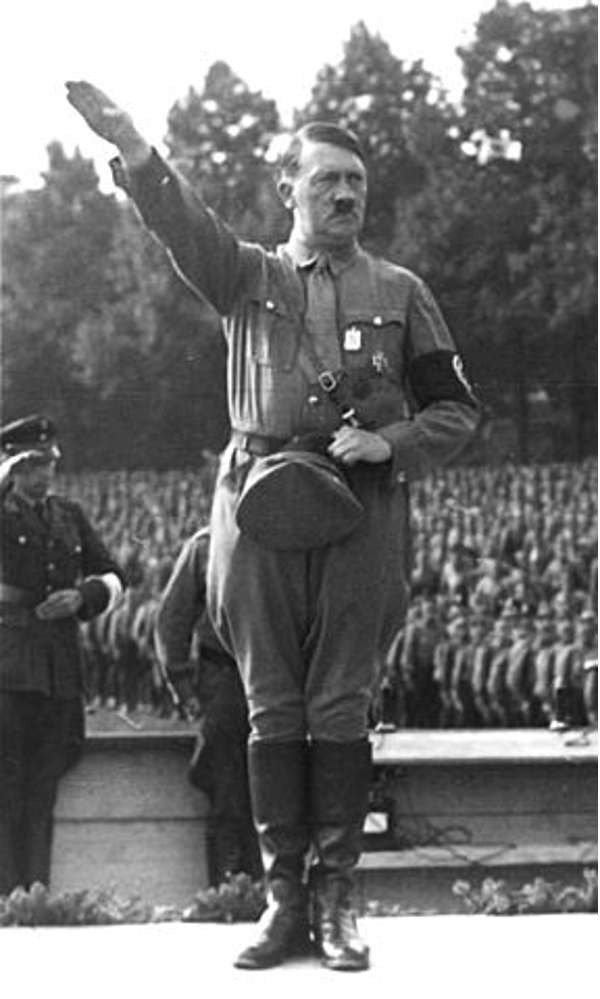

In essence, Classical Realism is a foundational theory of global politics. It lays out the argument that we live in an anarchical world, constituted by egoistic states that rationally and predictably pursue power because of the self-help imperative. This means global politics is predictable and, therefore, scientific. However, critics argue that Classical Realism rests on a very non-scientific foundation – the assumption that human nature is egotistic and conflictual, or as Morgenthau argued, the universal ‘desire of man to attain maximum power.’

Figure 2-17: Nürnberg.- Reichsparteitag der NSDAP, “Reichsparteitag des Sieges”, Adolf Hitler und Ernst Röhm in SA-Uniform, 30. August – 3. September 1933 Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=reichsparteitag+hitler&title=Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Nürnberg_Reichsparteitag_Hitler_retouched.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 de Courtesy of Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1982-159-22A.

Neo-Realism/Structural Realism

Structural Realism does not deviate from the prescriptions of Classical Realism. They still adhere to the four basic premises established by Classical Realism. First, humans seek protection and prosperity through groups. In the Westphalian System, the state is the highest form of human collective. Second, states, like humans, are rational and egoistic actors. This means we can predict what they are going to do. Third, due to inequality between actors, there will be tension and competition between actors as their interests collide. Fourth, given the anarchical nature of the global system, all states will rationally pursue self-help. Where Structural Realists deviate from Classical Realists is the basis of their world view. Classical Realism, in the end, roots its world view and subsequent policy prescriptions in human nature. It is rooted in a Judeo-Christian ethos of the fall from grace. This is a difficult position to maintain when you are seeking to establish a scientific basis for the study of global politics. In response to this criticism, Kenneth Waltz published the Theory of International Politics in 1979, which sought to establish a truly objective basis of the Realist canon. He accomplished this by looking to the systemic, or structural, aspect of global politics, anarchy. He notes that all states are functionally similar as they are sovereign states acting under the condition of anarchy. In other words, they are non-differentiated units. As a corollary to this, unit-level variables, like the type of government or particular leaders, are not important. China will do, what the US will do, what Canada will do, because they are all sovereign states operating under the condition of anarchy – they will seek to promote their interests as defined by power. So what determines state action? Why do states, who are non-differentiated and have the same purpose, act differently? According to Waltz, it comes down to capabilities defined as the distribution of resources. His argument boils down to this equation:

State Behaviour = Non-Differentiated Units + Anarchy + Capabilities

State Behaviour = Non-Differentiated Units + Anarchy + Capabilities

Therefore: State Behaviour = Capabilities defined in terms of the distribution of resources.

Or, the strong will do what they want, and the weak will do what they must.

However, Structural Realism is not a cohesive body of theory. Others have built on and critiqued Waltz’s scientific approach to the study and practice of global politics. The main critique of Waltz’s Neo-Realism is that it is overly deterministic – but this is a critique we will touch base on when discussing Neo-Classical Realism.

Building off of Waltz’s work, a number of discrete, and at times contradictory, approaches to Structural Realism have sought to find objective means to explain global politics and prescribe policy behaviour. Some have focused on the polarity of the system. Is a Unipolar, Bipolar, or Multipolar world more peaceful and stable? For Structural Realists, this explains the different policy dynamics at play between the multipolar Concert of Europe (1815-1914), the bipolar Cold War (1947-1991), and America’s brief unipolar moment (1989-1990s?). Most Realists argue that a multipolar world is most unstable, as it is more difficult to achieve a balance of power. A unipolar world sounds stable, but it also invites discontent by other powers that resent their privileged position in the system. A bipolar world sounds contentious, and the Cold War did do a lot of harm, but it is simple and provides predictability. Another debate in Structural Realism is the tension between ‘defensive realists’ and ‘offensive realists.’ Defensive Realism suggests states should seek security through moderate policies that achieve the national interest without being too aggressive and provoking retaliation and backlash. Offensive Realism, on the other hand, argues for power maximization and, if possible, domination and hegemony. For example, the security dilemma suggests that when one state becomes more powerful, they become a threat to other states. These ‘other’ states seek to balance against this threat and are, in turn, perceived to be a security threat. This creates a cycle of insecurity – much as we saw during the US/USSR arms race, and we see with actors pursuing Weapons of Mass Destruction to counter regional or great power influence.

The strength of Structural Realism is two-fold. First, it provides a more scientific basis for Realist analysis and policy prescriptions. Second, and related to the first, the scientific study of global politics has facilitated the identification of testable variables, like system polarity, Offensive vs Defensive Realism, and security dilemmas. The weakness in Structural Realism is its overly deterministic character: if capabilities determine behaviour, how do we explain variance in state policy choices? Moreover, if global politics is scientific and, therefore, predictable, why did Realists fail to predict major global changes, like the end of the Cold War?

Figure 2-18: The Fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989. The photo shows a part of a public photo documentation wall at the Brandenburg Gate, Berlin. The photo documentation is permanently placed in the public. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:West_and_East_Germans_at_the_Brandenburg_Gate_in_1989.jpg#/media/File:West_and_East_Germans_at_the_Brandenburg_Gate_in_1989.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Lear 21.

Neo-Classical Realism

Neo-Classical Realism is a relatively new theoretical stream. It seeks to balance the insights of Classical Realism and Structural Realism. It posits that the structural condition of anarchy and the relative distribution of power sets the parameters of global politics – just as Structural Realism suggests. In other words, capabilities define what is possible in a anarchical system constituted by competing self-interested actors. But it is also posits that individual and state-level variables matter, something Classical Realism suggests in its focus on diplomatic and military history. At the individual level, the quality of political leadership matters. At the state level, the form of government, the influence of elites, and identity constructs matter. The essential argument of Neo-Classical Realism is that there is an imperfect transmission belt between systemic prompts and policy responses. This suggests there is a range of policy responses to any given situation. This, in turn, relaxes the determinism of Structural Realism and, by extension, allows for agency in state policymaking. Neo-Classical Realism has been most developed in the field of foreign policy analysis.

The strength of Neo-Classical Realism is that it provides a more dynamic view of global politics. Therefore, it provides more insight into specific policy choices, by specific states, in specific contexts than Classical and Structural Realism. However, it is also less parsimonious and generalizable than the other two variants of Realism – the things that many Realists believe distinguish their theory from other approaches.

Figure 2-19: Tehran Conference. The “Big Three”: From left to right: Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill on the portico of the Russian Embassy during the Tehran Conference to discuss the European Theatre in 1943. Churchill is shown in the uniform of a Royal Air Force air commodore. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tehran_Conference,_1943.jpg#/media/File:Tehran_Conference,_1943.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Over the duration of this course there are questions to consider about the topics we engage with. Copy the following questions into a journal you are keeping, such as a Word Document, and respond to the questions. Over the term you will be asked to submit portions of this journal as part of the evaluation framework.

- Why are Liberalism and Realism considered status-quo or mainstream theories of global politics?

- What role do reason and rationality play in Liberal approaches to global politics?

- What distinguishes the different variants of Liberal approaches to global politics?

- Why are realist approaches to global politics dismissive of utopian approaches to global politics?

- What distinguishes the different variants of Liberal approaches to global politics?

- Why are both Liberalism and Realism considered problem-solving theories?

In module two, we have set out the mainstream approaches to global politics, namely Liberalism and Realism. These two approaches have dominated the study of global politics for much of the 20th century. These two approaches are considered mainstream or status quo theories in that they do not fundamentally question the system as it is currently constituted. Realist approaches are the most dogmatic in that they focus exclusively on the self-interested states operating under the condition of anarchy. Liberal approaches are a bit less dogmatic. They recognize the importance of other actors, including individuals, MNCs, and institutions. But they still admit the state is a self-interested actor operating under the constraints of anarchy. Both Liberalism and Realism are problem-solving approaches to global politics, even if they disagree on how to solve them. Liberal approaches to global politics are rooted in the belief that it is possible to use reason and rationality to overcome the problems we face. It is rooted in a desire to overcome the horrors witnessed in the trenches of World War One. For Liberal approaches, the solution to the inhumanity and carnage that has defined global politics can be found in supporting democratic movements, international institutions, international law, and economic interdependence. Realist approaches take a very different view. They believe the attempt to tame global politics is utopian, foolhardy, and dangerous. Rather, Realist approaches suggest we need to recognize that global politics is a distinct field of study that cannot be held to the moral or ethical standards of individuals and societies. Rather states must do whatever is necessary to protect their interests, defined in terms of power. Realists don’t think we can overcome the system unless we adopt a world government or a global empire – two options they think to be highly unlikely. That does not mean that Realists believe we cannot achieve peace. Peace is possible by acting on the world as it is and not as we want it to be. That if we recognize how each state’s relative capabilities dictate what they should do, peace, or at least order, is possible. In the end, from a Realist perspective, perhaps that is the best that can be expected – peace defined as global order, whether that order is just or not. However, in module three, we will question those assumptions that Liberalism and Realism take for granted – anarchy, states, and power.

Figure 2-20: Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/7Z-Uayu13ps Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Benigno Hoyuela on Unsplash

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Liberal Internationalism: the idea that progress is possible in global politics by recognizing the natural harmony of interests between all people

Democratic Peace Theory: the argument that democratic states do not go to war with each other

Neo-Liberal Institutionalism: explains the possibility and prevalence of cooperation in global politics by recognizing the formal and informal networks and institutions that create increased interdependence.

Classical Realism: a reaction to the utopian arguments following World War One, which sought to establish a scientific study of global politics, defined by self-interested states pursuing their national interest in an anarchical system.

Structural Realism: sought to establish a scientific basis for the Realist world view, identifying anarchy as the defining characteristic. Structural Realists argue that state behaviour = non-differentiated units + anarchy + capabilities.

Neo-Classical Realism: combines Classical Realism and Structural Realism's insights to better account for the imperfect transmission belt between systemic imperatives and policy choices.

Offensive Realism: the position that states should take every opportunity to maximize state power and, if possible achieve dominance or hegemony

Defensive Realism: the position that states should seek security and not power as too much power might provoke retaliation by other states

Security Dilemma: the circular logic whereby the increase in state A's power or capabilities provokes other states to balance against that state internally. State A perceives their increased power not as balancing but as a threat, setting off another round of power or capabilities increase.

System Polarity: the international system can be unipolar (1 hegemonic state), bipolarity (2 Great Powers), multipolarity (more than 2 Great Powers)

References

Bain, William. "Continuity and Change in International Relations 1919–2019." International Relations 33, no. 2 (2019): 132-41.

D'Agostino, Anthony. "Global Origins of World War One. Part Two: A Chain of Revolutionary Events Across the World Island." Historia Actual On-line, no. 13 (2009): 61-77.

Henig, Ruth. "A League of Its Own: The League of Nations Has Been Much Derided as a Historical Irrelevance, but It Laid the Foundations for an International Court and Established Bodies That the United Nations Maintains Today.(History Matters)." History Today 60, no. 2 (2010): 3.

Keohane, Robert O, and Joseph S Nye. "Power and Interdependence." Survival (London) 15, no. 4 (1973): 158-65.

Noesselt, Nele. "Is There a "Chinese School" of IR?" IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEc, 2012, IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEc, 2012.

McCarthy, Niall. “The Biggest Military Budgets as a Share of GDB in 2019.” Forbes, April 27, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2020/04/27/the-biggest-military-budgets-as-a-share-of-gdp-in-2019-infographic/#73e1a98337f1

Oord, Christian. “Believe it or Not: Since Its Birth The USA Has Only Had 17 Years of Peace.” War History Online, Mar 19, 2019. https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/usa-only-17-years-of-peace.html#:~:text=Believe%20it%20or%20Not%3A%20Since%20Its%20Birth%20The,American%20War%20of%20Independence%20from%201775%20to%201783

Wohlforth, William. “Realism and Security Studies” in Routledge Handbook of Security Studies. Second ed. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2017.

Supplementary Resources

Baylis, John, Owens, Patricia, and Smith, Steve. The Globalization of World Politics : An Introduction to International Relations. Seventh ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Jönsson, Christer, Weiss, Thomas G., and Wilkinson, Rorden. "Classical Liberal Internationalism." 105-17. 2013.

Więcławski, Jacek. Understanding Realism in Contemporary International Relations : Beyond the Structural Realist Perspective. 1st ed. Baden-Baden, Germany: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 2019.