When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the roots and purposes of Just War Theory

- Explain the differences between traditional and modern Just War Theory

- Explain war as an institution

- Explain Jus Ad Bellum, Jus In Bello, and Jus Post Bellum

- Critically apply Just War Theory to contemporary global politics

Walzer, Michael. “Ch 3 The Rules of War” Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations. New York: Perseus, 1977.

Renegger, Nicholas. “The Ethics of War: the Just War Tradition”, in Bell, Duncan. Ethics and World Politics. 2010.

- Institution

- Just War Theory

- Jus Ad Bellum

- Jus In Bello

- Just Cause

- Right Authority

- Right Intent

- Proportionality

- Last Resort

- Reasonable Chance of Success

- The Aim of Peace

- Proportionality of Means

- Non-combatant Immunity

- Raison d’état

- Just Post Bellum

Learning Material

In module 5, we introduced and discussed the concepts of anarchy and security in global politics. While our theories and approaches of global politics might understand the form and function of anarchy differently, they all recognize the current system is anarchical. Further, they all acknowledge that the condition of anarchy has security implications.

Figure 6-2: Source: https://flic.kr/p/4a3WcT Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of The U.S. Army.

The most critical security implication is war. A declaration of war is often the final tool in the state’s policy toolkit. As Carl von Clausewitz, the 19th-century Prussian general and military theorist, argued, “War is nothing but the continuation of politics with the admixture of other means.” (2007) This quote suggests that a declaration of war is on a continuum of policy options for states pursuing their respective national interests. In common parlance, war is the state of armed conflict between two or more sovereign states, between two or more groups within one state, or between two or more states and non-state actors. In the social sciences, sociology or politics, for example, war is seen as an institution. Institutions are defined as the formal/written rules, informal norms, or shared understandings that constrain or prescribe human interaction. Therefore, when we say war is an institution, we are saying that there are norms, rules, and/or understandings on the meaning and prosecution of war. ‘Just War Theory’, the focus of this module, is the most explicit attempt to make sense of war’s institutional aspects in the discipline of global politics. Just War Theory emerged in the Middle ages, building on Christian theology, Roman norms of war, and the political/military practices of the times. Just War Theory has evolved in tandem with changing norms/practices, rules/laws, and norm entrepreneurs’ advocacy. Despite the evolution of Just War Theory, it still addresses the same two questions: when war is justified and what actions are permissible during war. In many ways, this seems counter-intuitive. How can states, under the condition of anarchy, be stopped from using war as a policy instrument? And even more puzzling, why should some weapons and tactics be banned in the time of war? This module will tackle these questions: the intent and evolution of Just War Theory, the implications of Just War Theory, and where Just War Theory sits in our theories and approaches to global politics.

While the use of coercive force is a near-constant in the study and practice of politics, it also poses a near-eternal dilemma: when is coercive force legitimate and who has the legitimate authority to use coercive force? These dilemmas are not unique to global politics. For example, there are many questions regarding the legitimate use of coercive force by the state against its own citizens and foreigners on its territory. These are questions around the right to detain people, the right to use lethal force, the right to incarcerate people, et cetera. These are not black and white questions but rather questions with evolving and contextual answers. The dilemmas on the coercive use of force in domestic politics are amplified in global politics due to the condition of anarchy and the lack of deeply shared political, cultural, and legal norms. However, in both domestic and global politics, these debates on the legitimate use of coercive force are about issues of order, ethics, and accountability. Just War Theory is the most comprehensive attempt to codify the legitimate use of coercive force in global politics. However, to understand the contemporary form of Just War Theory, we need to start with its historical roots.

From the outset, it is important to note that Just War Theory is Eurocentric. It emerged out of Medieval debates on the ethics of war, both in terms of initiating war and the conduct of war. It has evolved through the establishment of the Westphalian State System and the institutionalization of this system through bodies like the Hague Conferences, the Geneva Conventions, the League of Nations, the United Nations, and the Responsibility to Protect. However, that is not to say other non-western polities do not have similar debates on war ethics. A significant body of work on the ethics of war emerged in China’s Warring States era in the 3rd century BC. There are both Hindu and Sikh texts that struggle with the concept of ‘just’ war. Islam also has a robust treatment of the rules and conduct of war. However, while Just War Theory may be very much in the Western tradition, the interconnectedness of globalization and the relative increase of non-western powers has created some space for a more inclusive debate on Just War Theory.

The roots of contemporary Just War Theory can be traced to the writing of St. Augustine (3rd and 4th century) and in the Arabic era of ‘intellectual flourishing’ (9th to 12th centuries). But it really took shape with St. Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century and the publication of Summa Theologicae. He argues that war is legitimate under three conditions:

- War must be waged by a legitimate public authority

- There must be a just cause

- There must be a rightful intention

Figure 6-3: St. Thomas Aquinas. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St-thomas-aquinas.jpg#/media/File:St-thomas-aquinas.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Carlo Crivelli.

Francisco de Vitoria (16th century) refined Aquinas’ work to try and solve the dilemma of perceived justness. In war, both parties often believe themselves on the side of righteousness. However, using Aquinas’ three conditions, that is not possible – both sides cannot have just cause and rightful intention. Further, in the prosecution of war, both sides may act unjustly by committing various atrocities. In his work, he separates out two defining aspects of Just War Theory: Jus Ad Bellum and Jus In Bello.

Jus Ad Bellum refers to the justice of war itself – in other words, when is it just to go to war. There are seven principles used to judge whether a particular war is just:

- Just Cause – the declaration of war must be in response to a genuine wrong being committed against the declarer

- Right Authority – the declaration of war must be made by an actor with the legitimate right to do so, for example, the state

- Right Intent – this applies to both the reason for declaring war and the means employed in the prosecution of war

- Proportionality – the goals of declaring war must be in proportion to the harm committed to the opposing state

- Last Resort – for war to be just, all other means of redress should be exhausted

- Reasonable Chance of Success – if it all but impossible to achieve the proportional goals of war, it cannot be just

- The Aim of Peace – war can only be a last resort effort in re-establishing a peaceful order

Each of these principles raise interesting questions. For example, what threshold constitutes ‘just cause’? For example, did Russia have ‘just cause’ when invading and annexing Crimea in defence of ethnic Russian separatists? In the case of ‘right authority’, can revolutionaries, like the Irish Republican Army or the Kurds, justly engage in conflict? Who is to determine the ‘right intent’? How do we measure proportionality, whether the use of force was a last resort, and whether there is a reasonable chance of success? For example, did the American invasion of Afghanistan following 9/11 have the right intent? Was the use of force the last resort? Was it proportional? Was there a reasonable chance of success? All of these questions highlight the subjective nature of assessing Jus Ad Bellum and perhaps suggests that the victor may, to a significant degree, define the ‘justness’ of a conflict.

Figure 6-4: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2014_%D0%9A%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%BC.PNG Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Роман Днепр.

Jus In Bello refers to justice in the prosecution of war – in other words, what is permissible in warfare. There are two conditions used to judge if the conduct of war is just:

- Proportionality of Means – the means of war must be in kind to the means employed against you

- Non-combatant Immunity – non-combatants include civilians, prisoners of war, and anyone not actively engaged in conflict against you.

While Jus In Bello seems much more straightforward than Jus Ad Bellum, there are still significant questions that are difficult to answer. For example, in an age of total war, is it justifiable to bomb a munitions factory? How about carpet bombing entire cities that are the industrial hub of a war-making effort? The allied powers used 722 heavy bombers in 1945 to drop 3,900 tons of high explosives and incendiary bombs on Dresden. The result was roughly 25,000 casualties and the flattening of 6.5 square km of the city center. The stated, albeit disputed, objective was to destroy factories, transportation hubs, and communications networks. Was this proportional? Can the 25,000 deaths all be combatants? To take things up a notch, can the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and/or Nagasaki be just? How about the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction? These examples illustrate the complexity of apply classical Just War Theory to the modern world, a topic we turn to in the next section. However, before doing so, it is important to close with one last point. If we separate Just War Theory into considerations of Jus Ad Bellum and Jus In Bello, we can address different questions. When assessing Jus Ad Bellum, we evaluate if the political leadership is ‘just’ in declaring war. When assessing Jus In Bello, we evaluate if the orders, tactics, and weapons employed in the conduct of war are ‘just’. Therefore, it is possible to have a war ‘justly’ declared but conducted in an ‘unjust’ way. Or vice-versa, a war declared ‘unjustly’ could be ‘just’ in its conduct.

Figure 6-5: Source: Dresden 1945 – 90% of the city was destroyed. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-Z0309-310,_Zerst%C3%B6rtes_Dresden.jpg#/media/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-Z0309-310,_Zerstörtes_Dresden.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 de Courtesy of Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-Z0309-310

St. Thomas Aquinas and Francisco de Vitoria’s work established the general framework of Just War Theory that is applied today. First, they established an argument that war was an institution and therefore had norms, rules, and laws attached to it. While they recognized, and to a degree bemoaned, the perennial nature of war, they argued that it should not be indiscriminate. For example, if a neighbouring state engaged in a border skirmish or raid, it was not acceptable to apply the full military might of your state in response, perhaps conquering and burning your neighbour’s capital to the ground. To give a contemporary illustration, it would have been unacceptable for the United States to launch a nuclear attack against Kabul in response to the al Qaeda attack on the twin towers on 9/11. Second, they laid out two broad categories with which to judge war – Jus Ad Bellum and Jus In Bello. These two categories allow us to parse conflict and establish responsibility for a breach of norms, rules, and laws. If a state were to declare a war unjustly, the responsibility falls to the state or perhaps to its political leadership. If a military officer were to issue illegal orders or a soldier were to undertake illegal action, the responsibility falls on the particular individual.

The general framework of Just War Theory remains influential to this day – especially the concepts of Jus Ad Bellum and Jus In Bello. In other words, when is it just to declare war and what tactics/weapons can be justly used in war. However, modern Just War Theory is also markedly different from the traditional ideas of people like Aquinas and Vitoria. The classical ideas of Just War Theory are deeply rooted in the fluidity and Christian ethic of Medieval Europe. This Eurocentric basis of Just War Theory meant that combatants shared religious, cultural, and moral norms and values. They recognized the enemy as having those shared attributes. The military was largely professional, and even when facing an enemy, they shared a sense of role and appropriate behaviour in war. They saw themselves in the enemy. This recognition limited what they were willing to do to their peers on the battlefield. Perhaps most importantly, early theorizing on war emerged from generalizing on the practices of war which were based on these shared norms and values.

Beyond the framework of Jus Ad Bellum and Jus In Bello, the modern versus traditional variants of Just War Theory differ significantly. Modern Just War Theory is secular and universal versus Christian and Eurocentric. The secular element derives from the context of contemporary global politics, which privileges the state. The rise of the state came with the expectation that the state has the right to use force to protect and promote its political interests. These political interests were increasingly divorced from religious judgement, and raison d’état, or reason of state, took precedence. Raison d’état argues the national interest of the state overrides conventional legal or moral considerations. The rise of the state sharply divided domestic and foreign spheres. Domestically, the state has a monopoly on the use of force. In terms of foreign affairs, the state is responsible for protecting its borders, and it has a privileged position in international diplomacy and law. We have discussed this process before. But it also comes with several accompanying changes that deeply transformed Just War Theory. Medieval subjects transformed into citizens. Small professional armies transformed into mass mobilization. Set battles transformed into total war. The Westphalian State System became the ordering principle of global politics through imperialism and colonialism. Finally, war has become larger, more deadly, and, with WMDs, existential. With the combination of the globalized state system and the increased threat war poses, Just War Theory has become universal. While traditional Just War Theory emerged out of the political, diplomatic, and warfare practices of Medieval Europe, modern Just War Theory has been globalized. It applies to all states. Importantly, Just War Theory is no longer a bottom-up approach that reflects generalized practices. Instead, it is now primarily, although not exclusively, a top-down approach based on political philosophy and imposed through international institutions and international law.

Figure 6-6: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:East_timor_independence_un2.jpg#/media/File:East_timor_independence_un2.jpg Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of Geoggrey C. Gunn.

So what does modern Just War Theory look like? The basic framework is the same. It seeks to assess when it is justified to go to war, Jus as Bellum, and what weapons and tactics are permissible in the conduct of war, Jus In Bello. At the broadest level, both variants of Just War Theory seek to limit the most tragic aspects of war: protecting and establishing the rights of non-combatants, medical units, and prisoners of war, for example. However, the world today is very different than that of Medieval knights. The two world wars, the development of WMDs, the concept of international humanitarian law, and the fear of transnational terrorism create a new environment. In response, states have created institutions of global governance, namely the League of Nations and the United Nations, which have outlawed aggression. International agreements on human rights have been established, from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) to agreements that deal with civil, political, racial, economic rights. There are international covenants that deal with the rights of women, children, people with disabilities, refugees, and migrants. There are prohibitions against torture and the use of weapons such as WMDs, most notably nuclear weapons, and other indiscriminate weapons like chemical and biological agents as well as landmines and cluster munitions. The agreement with the most potential to transform global politics, albeit not yet in practice, is the Responsibility to Protect. R2P makes state sovereignty conditional on protecting citizens from gross human rights abuses. All of this transforms when it is justified to go to war as well as what weapons and tactics are permitted in the prosecution of war. For example, what now constitutes ‘just cause’? In modern Just War Theory, just cause is limited to self-defence and retaliation for armed conflict. For instance, in terms of ‘just cause’, the US invasion of Afghanistan post 9/11 is potentially ‘just’, while the invasion of Iraq would not be. However, R2P suggests the defence of civilians in other states constitutes ‘just cause.’ Yet, this raises another question, who is the ‘right authority’? To act on R2P or to use any force outside of self-defence requires UN Security Council authorization. This makes the UNSC the ‘right authority,’ not the state, but this is in tension with our state-based world – the UN does not have a standing army but rather requires states to contribute troops. The issues of ‘right intent’ and ‘proportionality’ are also problematic. In applying R2P in Libya, the coalition forces were authorized to protect civilians, for example, by creating a no-fly zone. But that mission quickly transformed into regime change. Did this have the right intent? Was it proportional? How about the War on Terror? Was it proportional, and did it have the right intent? Even more importantly, was there a reasonable chance of success? What would that even look like? Finally, given the destructiveness of contemporary conflict and the recognition that this destruction can foment new conflict, some have introduced a third category to the Just War Theory framework, Jus Post Bellum. Just Post Bellum argues that post-war destruction also needs to be addressed for a war to be just. This would include post-war reconstruction, humanitarian assistance, and support for state-building.

Figure 6-7: Source: https://flic.kr/p/4yRwTC Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of The U.S. Army.

All of this suggests a few take-away points. First, the destructiveness of modern war and the increased accessibility of WMDs has fostered a renewed interest in a secular and universal Just War Theory. However, such a modern Just War Theory also exposes the indeterminacy of global politics. It highlights the tension between a state-based world and the institutions of global governance. It highlights the hypocrisy between the rights of small to medium states with that of the Great Powers and, most specifically, the UNSC P5 members. Modern Just War Theory also raises important criticisms. Some argue that Just War Theory enables rather than prevents the use of war by stipulating when it is permissible to use war. Others argue that the application of Just War Theory will always result in law trying unsuccessfully to catch up with technological innovation.

More importantly, Just War Theory critics point to the trump card of expediency and the Eurocentric nature of Just War Theory. In terms of expediency, critics argue that military, and potentially political, necessity will always trump moral restraint when push comes to shove. For example, while the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki can not be considered ‘just’, they served the US’s military and political interests. Militarily, the atomic bombs shortened the war, prevented the meat grinder of island hopping towards Japan, and saved American lives, albeit at great cost to Japanese lives. Politically, Truman would have faced intense criticism if he did not use the new weapons on Japan. According to Just War Theory, these bombings were unjust. They were not proportional. They were not the last resort. And with evidence suggesting they were as much a warning to the USSR as they were an attack on Japan, the bombings were of questionable intent. Finally, critics point to the Eurocentric legacy of Just War Theory. While modern Just War Theory is intended to be secular and universal, it is still clearly built on a Christian foundation. This criticism reveals a critical dilemma in many issues of global governance. How can Just War Theory, or any agreement emerging from a system built on western norms, be just? Is this another example of the minority world imposing its values on the majority world? Or can it be argued that although Just War Theory is built on a Christian foundation, the modern variant’s secularity renders it universal? Or is it a matter of practicality? Do we need to recognize the Eurocentric nature of global politics and act on it as it is versus some impossible ideal of a truly universally derived code of conduct? These are questions with implications far beyond Just War Theory. But they are questions that need an answer, even if they will be extremely challenging to address.

Figure 6-8: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atomic_bombing_of_Japan.jpg#/media/File:Atomic_bombing_of_Japan.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of George R. Caron – Nagasakibomb.jpg Atomic_cloud_over_Hiroshima.jpg

Modern Just War Theory attempts to build a contemporary and relevant framework to adjudicate when the use and practices of war are just. It aims to be secular and thus relevant to our state-based world. It aims to be universal, applying to all states, in all places, and at all times. For some, it is a necessity given the increasingly destructive tools of modern war and the potential for total war. For others, Just War Theory is another example of the domination of global governance through the imposition of western culture and norms. Critics point to the issues of effectiveness, feasibility, and hypocrisy in modern Just War Theory. Yet, given contemporary examples of violence both between and within states, Just War Theory provides a means to critically assess the use and prosecution of war.

It is useful to look at Just War Theory through the lenses of our theories and approaches to global politics. Realism and Liberalism are most compatible with modern Just War Theory. Realism poses an interesting case. On the one hand, Realism would refute any limitations placed on the state in striving to achieve its national interest. Realism is still very much embedded in the raison d’état tradition. Given the assumptions of groupism, anarchy, and self-help, Realism argues that the national interest is first and foremost about survival. Further, any application of common morality to state action is not only misguided, it is potentially an existential threat. Therefore, Realists may lament the need to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But that would not stop them from recommending Truman to do so. In so doing, he prevented American deaths and sent a warning to the USSR, a soon-to-be Cold War rival. Truman’s duty is to his citizens and to protecting the American national interest. However, there are two ways in which Realism is compatible with Just War Theory, albeit uneasily and more comfortably with the traditional variant. First, Realism would align with Just War Theory’s traditional privileging of the state as the ‘right authority’. Realism does not recognize the legitimacy of decision-making bodies above the states. As a corollary to this, Realism also aligns with the idea that a just war pursues state interests, not ideological goals nor universal ambitions. Second, while many Realists argue foreign policy should be amoral, it does contain an implied ethic of prudence. Given the potential for conflict at any time, Realists argue the state must always err on the side of caution, for to do anything less would put the state at risk. In terms of Just War Theory, this aligns with the concept of proportionality and only engaging in conflicts that have a reasonable chance of success. However, while Realism does align with some aspects of Jus Ad Bellum, it would align less with Jus In Bello. Realism does not recognize international norms, rules, or laws to restrict how a state may protect itself – for Realism expediency will always trump moral restraint. However, some Realists recognize the role of proportionality in Jus In Bello, since the threat or application of overwhelming force could both prolong a conflict and generate deep antipathy post-conflict, creating more insecurity.

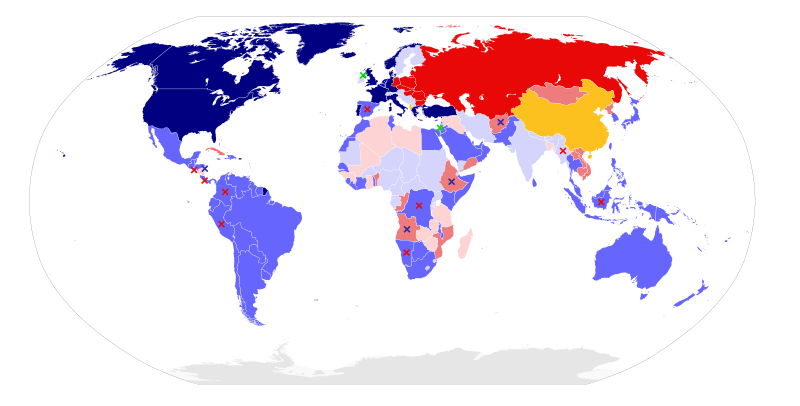

Figure 6-9: Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/Cold_War_Map_1980.svg/800px-Cold_War_Map_1980.svg.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of MinnesotanConfederacy.

Figure 6-10: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emblem_of_the_United_Nations.svg#/media/File:Emblem_of_the_United_Nations.svgPermission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Spiff~enwiki.

Liberalism is perhaps the most aligned with modern Just War Theory. Modern Just War Theory sits comfortably with Liberalism’s status quo effort to overcome the problems generated by anarchy and to overcome the scourge of war. Liberalism seeks to use reason and rationality to achieve progress in global politics. To do so, Liberals employ institutions, pursue interdependency, and seek to establish legal regimes. Modern Just War Theory fits nicely here. It seeks to establish a secular and universal framework to judge the use of force in global politics. It recognizes the role of institutions like the UNSC and the International Criminal Court. It seeks to build a body of law that bans the use of some weapons and to restrict when/how states can legitimately use war as a tool of statecraft. This includes things like needing UNSC approval to use force and banning weapons like WMDs and landmines. However, perhaps most notable is R2P, which Liberals argue forces states to be accountable to their citizens’ fundamental rights or risk losing their sovereignty. However, the two possibly most closely align in that they are both status quo approaches to global politics. They are both seeking to limit the worst excesses of the system without fundamentally changing it. Yet, Liberalism and modern Just War Theory also share a weakness that expediency often overcomes ideology and moral arguments in the heat of battle.

Figure 6-11: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crécy_-_Grandes_Chroniques_de_France.jpg#/media/File:Crécy_-_Grandes_Chroniques_de_France.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Constructivism, as usual, sits between the status quo theories and outside-the-box approaches to global politics. Constructivism would be most interested in four questions relating to Just War Theory. First, how and why has Just War Theory evolved from Aquinas’s writing to the writing of Walzer? In other words, how have the shared understandings of what constitutes a just war evolved? Of particular interest is the transformation of a tradition rooted in Medieval European Christian morals into a secular and universal theory of war. Second, and related to the first point, who were the norm entrepreneurs championing Just War Theory? To what degree were they successful in challenging existing norms of war? Third, Constructivists would be interested in the degree to which modern Just War Theory is accepted and internalized in global politics. Does the theory constrain what states and non-state actors do in practice? Finally, Constructivism would be interested in how Just War Theory influences the intersubjective and socially derived meaning attached to the institution of war. Does the very discussion of whether war can be ‘just’ influence how we understand the form and function of warfare.

Figure 6-12: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Air_Force_Basic_Training_Field.jpg#/media/File:Air_Force_Basic_Training_Field.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Master Sergeant Cecilio Ricardo – US Air Force Public Affairs.

Critical and Post-structural approaches to global politics would be highly suspicious of Just War Theory. First, Just War Theory maintains the status quo privileging of the state in global politics. Just War theory focuses on when war is permissible and what weapons and tactics may be used in its prosecution. It is not about who benefits from war, who fights the war, and who suffers the most from the consequences of war. At the broadest level, both approaches would have some sympathy for the ideals of R2P and the inclusion of Jus Post Bellum. However, they would be very critical of the application of both. Critical theorists and Post-structuralists have highlighted the many ways that R2P is most often used by the powerful for the interests of the powerful. For example, R2P was arguably employed in Libya because it was a security threat to Europe. It had no great power patronage to protect it in the UNSC. And it was a means of extending western and predominantly European influence in North Africa. However, there was no R2P mission in Syria, nor in support of the Rohingya in Myanmar, nor the Uighurs in China. This suggests that R2P is another tool in the arsenal of the powerful to reaffirm their structural power rather than promoting human security. Similarly, they would argue that Jus Post Bellum, or the need to address post-war reconstruction, is at best window dressing to reaffirm western benevolence and, at worst, another concept most often ignored in the name of expediency.

More specifically, Securitization Theory and Post-Colonialism offer a cutting critique of Just War Theory. When assessing Just War Theory, Securitization theory asks who or what is being securitized, by whom, and for what purpose. For example, Walzer suggests a Supreme Emergency justifies war, an idea used by proponents to justify the War on Terror. However, Securitization Theory would question this proposition. Instead, it argues that events like 9/11 and the attacks in Madrid (2004), London (2005), Paris (2015), and Brussels (2016) were used by the powerful to justify the seizing of extraordinary powers by western states. In so doing, these states created a perennial existential threat that justified their limiting of citizens’ freedom and embarking on foreign wars. Post-Colonial Theory argues that much of the cosmopolitan thread in Just War Theory, and human security, is used by the strong against the weak. In so doing, the structural privilege of the powerful is reaffirmed and strengthened. There are clear discursive practices at work in the language. It is ‘just’ war theory. It is ‘human’ security. But in practice, it is strong states using both Just War Theory and Human Security as a means to justify their structural dominance. Even the institutions at work privilege the strong over the weak. For example, the International Criminal Court prosecutes international crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes of aggression. However, the ICC did not prosecute the US for its use of torture at Abu Ghraib in Iraq. It did not prosecute the Chinese for genocide against Uighurs. It did not prosecute western powers’ use of drone strikes or targeted assassinations. However, the ICC has consistently prosecuted African states, and to a lesser degree, states in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and South America. Post-Colonial theorists argue this demonstrates how both Just War Theory and Human Security privilege the minority world as good, right, and just while the majority world is corrupt, lawless, and unjust.

Figure 6-13: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ICC_investigations.png#/media/File:ICC_investigations.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of ICCmemberstatesworldmap102007.png.

By applying our theories and approaches of global politics to Just War Theory, we are able to unpack some of its implications in practice. On principle, Realism opposes Just War Theory’s intent as it seeks to limit what a state may or may not legitimately do. However, it is interesting to note those areas that they do agree on, particularly the focus on states as the ‘right authority’ and the need to be judicious or prudent in the use of force. Just War Theory fits most comfortably in Liberal tradition as it tries to establish laws to control war while not challenging the system as it stands. Constructivism is agnostic on the utility or ethics of Just War Theory. However, it is very interested in the normative elements and how they have been agreed on or not. Both Critical and Post-structural approaches mount a robust critique of Just War Theory, arguing it is another means by which the strong legitimate their privilege in the system.

War is a constant of human relations as far back as recorded history exists. Traditionally, war was simply another policy tool for leaders to exercise in the pursuit of their interests. Given the perennial nature of war, political philosophers began to think about the ethics of conflict. In Medieval Europe, Just War Theory emerged out of Christian morality and the practices of combatants. Militaries at this time were small, professional, and used to in a fluid context of shifting political boundaries. Combatants may face each other on the field of battle, but, for the most part, they still saw themselves in the ‘other’. This meant they shared a moral identity that fostered implicit and explicit codes of conduct. This code of conduct was synthesized by thinkers such as St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Francisco de Vitoria to create Just War Theory. Just War Theory establishes when war is ‘just’ (Jus Ad Bellum) and what weapons and tactics are ‘just’ in the conduct of war (Jus In Bello). Just War Theory adapted to societal, military, and normative changes. Modern Just War Theory still deals with Jus Ad Bellum and Jus In Bello but it is now secular and universal. Rather than emerging from the practices of war between culturally similar combatants, it is now more normative in detailing what should be acceptable grounds for declaring war and what weapons and tactics should be acceptable in the conduct of war. It has to account for the history of two world wars, the new global governance institutions, and globalization’s interdependencies. Important considerations of modern Just War Theory are unsettled. Who is the right authority? What constitutes just cause? Without shared cultural norms and in the context of anarchy, how are the norms, rules, and laws of war to be enforced? These debates, especially in light of humanitarian intervention, have generated a call to expand Just War Theory to include Jus Post Bellum – the need for dealing with consequences of war post-conflict. Critics point out the issues of effectiveness, feasibility, and hypocrisy of Just War Theory. However, with all that being said, the sheer destructiveness of modern war almost necessitates a set of rules, norms, and laws on Jus Ad Bellum, Jus In Bello, and, perhaps, Jus Post Bellum.

Review Questions and Answers

Just War Theory emerged out of Medieval debates on the ethics of war, both in terms of initiating war and the conduct of war. The roots of Just War Theory come from the writing of St. Augustine (3rd and 4th century BC) and in the Arabic era of ‘intellectual flourishing’ (9th to 12th centuries). But it really took shape with St. Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century and the publication of Summa Theologicae. He argues that war is legitimate under three conditions: war must be waged by a legitimate public authority; there must be a just cause; there must be a rightful intention. Francisco de Vitoria (16th century) refined Aquinas’ work to try and solve the dilemma of perceived justness. In war, both parties often believe themselves on the side of righteousness. However, using Aquinas’ three conditions, that is not possible – both sides cannot have just cause and rightful intention. Further, in the prosecution of war, both sides may act unjustly by committing various atrocities. In his work, he separates out two defining aspects of Just War Theory, when it is just to go to war (Jus Ad Bellum) and what tactics and weapons are just in the conduct of war (Jus In Bello).

Modern Just War Theory is secular and universal versus Christian and Eurocentric. The secular element derives from the context of contemporary global politics, which privileges the state. The rise of the state came with the expectation that the state has the right to use force to protect and promote its political interests. These political interests were increasingly divorced from religious judgement, and raison d’état, or reason of state, took precedence. Raison d’état argues the national interest of the state overrides conventional legal or moral considerations. The rise of the state sharply divided domestic and foreign spheres. Domestically, the state has a monopoly on the use of force. In terms of foreign affairs, the state is responsible for protecting its borders, and it has a privileged position in international diplomacy and law. We have discussed this process before. But it also comes with several accompanying changes that deeply transformed Just War Theory. Medieval subjects transformed into citizens. Small professional armies transformed into mass mobilization. Set battles transformed into total war. The Westphalian State System became the ordering principle of global politics through imperialism and colonialism. Finally, war has become larger, more deadly, and, with WMDs, existential. With the combination of the globalized state system and the increased threat war poses, Just War Theory has become universal. While traditional Just War Theory emerged out of the political, diplomatic, and warfare practices of Medieval Europe, modern Just War Theory has been globalized. It applies to all states. Importantly, Just War Theory is no longer a bottom-up approach that reflects generalized practices. Instead, it is now primarily, although not exclusively, a top-down approach based on political philosophy and imposed through international institutions and international law.

Jus Ad Bellum refers to the justice of war itself – in other words, when is it just to go to war. There are seven principles used to judge whether a particular war is just:

- Just Cause – the declaration of war must be in response to a genuine wrong being committed against the declarer

- Right Authority – the declaration of war must be made by an actor with the legitimate right to do so, for example, the state

- Right Intent – this applies to both the reason for declaring war and the means employed in the prosecution of war

- Proportionality – the goals of declaring war must be in proportion to the harm committed to the opposing state

- Last Resort – for war to be just, all other means of redress should be exhausted

- Reasonable Chance of Success – if it all but impossible to achieve the proportional goals of war, it cannot be just

- The Aim of Peace – war can only be a last resort effort in re-establishing a peaceful order

Jus In Bello refers to justice in the prosecution of war – in other words, what is permissible in warfare. There are two conditions used to judge if the conduct of war is just:

- Proportionality of Means – the means of war must be in kind to the means employed against you

- Non-combatant Immunity – non-combatants include civilians, prisoners of war, and anyone not actively engaged in conflict against you

Given the destructiveness of contemporary conflict and the recognition that this destruction can foment new conflict, some have introduced a third category to the Just War Theory framework, Jus Post Bellum. Just Post Bellum argues that post-war destruction also needs to be addressed for a war to be just. This would include post-war reconstruction, humanitarian assistance, and support for state-building

Glossary

Institution: complex social forms constituted by relatively stable sets of roles, norms, and values that organize human activity

Jus Ad Bellum: refers to the justice of going to war itself and uses seven principles to assess whether a particular declaration of war is ‘just’

Jus In Bello: refers to what is permissible in warfare and uses two principles to assess whether the conduct of war is ‘just’

Just Cause: the declaration of war must be in response to a genuine wrong being committed against the declarer

Just Post Bellum: argues that post-war destruction also needs to be addressed for a war to be just.

Just War Theory: seeks to establish when it is ‘just’ to go to war and what is ‘just’ in the conduct of war

Last Resort: for war to be just, all other means of redress should be exhausted

Non-combatant Immunity: non-combatants include civilians, prisoners of war, and anyone not actively engaged in conflict against you

Proportionality of Means: the means of war must be in kind to the means employed against you

Proportionality: the goals of declaring war must be in proportion to the harm committed to the opposing state

Raison d'état: argues the national interest of the state overrides conventional legal or moral considerations

Reasonable Chance of Success: if it all but impossible to achieve the proportional goals of war, it cannot be just

Right Authority: the declaration of war must be made by an actor with the legitimate right to do so, for example, the state

Right Intent: this applies to both the reason for declaring war and the means employed in the prosecution of war

The Aim of Peace: war can only be a last resort effort in re-establishing a peaceful order

References

Bellamy, Alex J., Luis Cordeiro-Rodrigues, and Danny Singh. Comparative Just War Theory. An Introduction to International Perspectives. Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

Farrell, Michael. Modern Just War Theory: A Guide to Research. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2013.

Clausewitz, Carl Von. On War. Project Gutenberg, 2007.

Bruder, Beca. “The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki & Just War Theory.” Medium. December 6, 2017.

Banta, Benjamin R. "Just War Theory and the 2003 Iraq War Forced Displacement." Journal of Refugee Studies 21, no. 3 (2008): 261-84.

Morkevicius, Valerie. "Power and Order: The Shared Logics of Realism and Just War Theory." International Studies Quarterly 59, no. 1 (2015): 11-22.

Williams, Andrew J., Author, Williams, Andrew J., and Taylor & Francis. Liberalism and War: The Victors and the Vanquished. New International Relations. London; New York: Routledge, 2006.

Floyd, Rita. “Can Securitization Theory Be Used in Normative Analysis? Towards a Just Securitization Theory.” Security Dialogue 42, no. 4-5 (2011): 427-39.

Supplementary Resources

- Fisher, David. "Can a Medieval Just War Theory Address 21 St Century Concerns?" Expository Times, no. 4 (2012): 157-65.

- Lee, Steven. Intervention, Terrorism, and Torture: Contemporary Challenges to Just War Theory. Springer, 2007.

- Fotion, Nick. "Is Just War Theory Obsolete?" Religious Inquiries, no. 3 (2013): 47-62.