- Define Global Politics

- Explain the role of theory in studying contemporary issues of global politics

- Explain the types of theories used in global politics

Brown, Chris, (2019). Chapter 1- “Defining International Relations,” In Understanding International Relations, 5th Edition.

- Anarchy

- Complex Interdependence

- First Great Debate

- Fourth Great Debate

- Global Politics

- National Interest

- Politics

- Second Great Debate

- Sovereignty

- Structuralism

- Theory

- Third Great Debate

Learning Material

Figure 1-2: Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/hand-world-ball-keep-child-earth-644145/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of artistlike.

Welcome to POLS 261! Through the twelve modules of this course, we will be exploring the history, structure, and contemporary issues that define the study and practice of global politics. Two core concerns shape this class. First, what are the global issues that dominate global politics: war/peace, economics, terrorism, crime, human rights, Indigenous rights, and the environment, to name just a few. However, the goal in this course is not to just identify these issues but to explain/understand them and, more importantly, to debate the different prescriptions that academics and practitioners suggest for confronting them. This means we are going to connect issues with different theories and contrast what emerges. Consider theories as a type of prism. Just like a physical prism breaks sunlight into a rainbow, allowing us to see the different colours that make up white light, an academic theory breaks an issue into its constituent parts, highlighting different aspects depending on the prism being used. As we will see, Realism will privilege the need for security and prudence in dealing with global issues. Liberal approaches on the other hand, will privilege the centrality and benefits of individual rights. While Critical theories will unpack an issue to privilege the role of power and narrowly defined self-interest. Like a prism, each theory reveals and privileges different things and therefore prescribes different responses. As a student of global politics, each of these theories is part of your academic toolbox. And, much like a tool in a toolbox, not all theories are appropriate for all issues or questions. It is up to you to know which tool to use and when, which provides the most persuasive analysis, which prescription is achievable and will attain the best outcome. In this module, we are going to set out the framework of our enquiry. In the first section, we will define our subject, global politics and the field of International Relations. In the second section, we will introduce the form and function of theory. Together, these two sections will establish the boundaries of our course. In subsequent modules, we will use this framework to explore the theories and practices of global politics. So, prepare to dig into our exploration of global politics!

What is global politics? What boundaries delineate the issues and practice of global politics? Politics, most broadly defined, is about power and authority in a given community: or as Harold Lasswell argued, “who gets what, when, and how.” For most people, most of the time, politics is associated with the government and the things being done in Ottawa, Regina, and Saskatoon. Some may think a bit deeper and consider the relationship between the government and its citizens, and the reciprocal set of rights and obligations between them. More concretely, people often link politics with their everyday life and issues like taxes, policing, healthcare, education, and pensions. When most people think about global politics, they often use the same cognitive framework. This is a narrative of a state-based world divided into distinct sovereign countries with thick and meaningful borders. Just think about the standard world map you might see on the wall, with black line neatly delineating Canada from the US, India from Pakistan, and France from Belgium. In this world, global politics is constituted by diplomats residing in embassies and state capitals, all pursuing the national interest in a contested global context. Traditionally, these diplomats are seeking to prevent, or win, wars. They are seeking to maximize the potential benefits of trade. And they are seeking to build alliances and institutions that will further both goals. In more recent times, diplomats have had to respond to new international threats like climate change or pandemics and increasingly sophisticated and international networks of organized crime and transnational terrorists. This has required developing new tools, skills, and institutional arrangements.

However, others see a more complicated world where states are not so sovereign, and borders are not so thick nor so meaningful. They see a world increasingly interconnected through advances in transportation and communication technology, which has thinned these borders. As a result, what happens in one place can have a significant impact on distant places if not everywhere. Think about how environmental disasters like the Fukushima nuclear power meltdown sent plumes of radiation through the air and ocean or how CO2 emissions are linked to climate change which recognizes no borders. Think about how international finance never sleeps, moving from one financial capital to another in a never-ending cycle. While acknowledging the historical prominence and continuing significance of the state, they recognize the increasing importance of other actors that challenge the privileged position of the state. They see the power of Multinational Corporations that in many cases exceed that of small and/or developing states. For example, Walmart has an economy just slightly smaller than that of the Canadian government. They see how interests and civil society groups transcend borders, building networks of people pursuing shared interests, values, and/or beliefs. These can be a religious group, like the Christian evangelical NGO World Vision, the environmental NGO Greenpeace, or Oxfam, an NGO seeking to fight global poverty and inequality. These two opposing narratives of global politics set the boundaries of what we are studying in this class. On the one side, global politics is the study of a state-based world and on the other it is a world of individuals, groups, corporations, states, and institutions in a relationship defined by complex interdependence.

Figure 1-3: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/news-newspaper-globe-read-paper-1074604/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Importance and Impact

As you might have noted in Chapter One of Understanding International Relations, several core concepts define the debate over what constitutes Global Politics, or, as Chris Brown argues, International Relations. These are concepts that will reappear in subsequent modules but whose meaning may be contested or even contradicted. Therefore, before moving forward, it is important to clear some of this conceptual clutter. In particular, we will look at the concepts of sovereignty, anarchy, complex interdependence, and structuralism.

Figure 1-4: https://pixabay.com/photos/europe-map-1923-country-breakdown-63026/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of WikiImages.

Sovereignty is the assertion that someone or something is the supreme authority within a clearly delineated territory. The concept emerged and evolved in tandem with the modern state system in Europe. These early states were led by monarchies, where sovereignty was invested in the person, or sovereign, through the divine right to rule. The territorial aspect of modern states is rooted in the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), where the idea of non-interference in the domestic affairs of other states began to take shape – the signatories agreed to recognize each other’s authority within their respective states. As the European monarchies were undermined by revolution and democratic movements in the 17thand 18th centuries, sovereignty shifted from the individual to the territory; for example, from Louis the XVI to France. Now France, or Canada for that matter, are considered sovereign states that do not recognize any higher authority in their domestic affairs. However, it is important to note that this does not mean sovereign states can act freely. In order to achieve their goals, they compete with other sovereign states that may have conflicting goals. They must contend with domestic and international advocacy groups as well as MNCs. They must take into account their international agreements and obligations. One final note, the concept of the sovereign state is once again being challenged. Just as sovereignty shifted from the person to the state, doctrines such as the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) are arguing that sovereignty should shift from the state to citizens. R2P argues that if a state is unwilling or unable to protect its citizens from a gross abuse of human rights, the international community not only has a right but an obligation to intervene. This suggests that ‘sovereignty’ is not an unconditional right of the state, but rather, it is conditional on protecting a minimalist set of human rights. Sovereignty is an important concept in global politics. If we accept the state as unconditionally sovereign, then global politics is defined by thick borders, ambassadors, and embassies. If states are only conditionally sovereign, then global politics is more complicated with a more diverse set of actors.

Figure 1-5: https://pixabay.com/photos/industry-industry-4-web-network-2630319/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

The flip side of state sovereignty is anarchy. Anarchy is defined by the lack of an overarching authority. Since sovereign states do not recognize any higher authority, the international system is anarchic and is constituted by non-differentiated actors with equal legal standing. In other words, no state has any higher legal standing than any other state: Canada, China, and Costa Rica all hold equal legal standing in the world. The easiest way to conceptualize the anarchical nature of the international system is to contrast it with possible alternatives: world government or global empire. A world government means that there is one overarching political structure that has the authority to maintain global order, just like the government does domestically. A global empire means there is one actor that imposes order on the rest of the world. Think of the British who imposed order over an empire upon which the sun never set. While some argue embryonic forms of a world government or world empire exist, the UN as an example of the former and global capitalism or American cultural imperialism of the latter, both positions are far from challenging the dominant logic of international anarchy. Another way to conceptualize the anarchical system is to contrast it with a hierarchal system. The best example of a hierarchical system is the state where authority is nested within a political structure and actors are differentiated. In Canada, for example, the constitution sets out the authority of the three branches of government as well as the jurisdiction of the provinces and the federal government. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms establishes the rights and obligations of the state and citizens to each other. Cumulatively, they establish a particular form of order where everyone is under the rule of law. The definition and meaning of anarchy are important to the study of global politics. For some, anarchy, or more specifically, the lack of overarching authority, means global politics is a dangerous place and demands prudence from state leaders. For others, the meaning of anarchy is not a given – an anarchical system can be conflictual or it can be cooperative, depending on the meaning generated between actors.

The concept of complex interdependence challenges the simple view of a global politics constituted by unitary actors pursuing their national interest; a world where Canada, the US, and China are competing to achieve self-interested goals. Complex interdependence argues the global politics is constituted by a wide variety of actors, including sub-state agencies, corporations, civil society groups, and international institutions who work to form international regimes. These regimes regulate policies on a wide range of issues, including trade, security, development, pandemics, terrorism, the environment, and Indigenous rights. Importantly, complex interdependence suggests that these regimes, once constituted, may operate independently of the actors that created them. This view is significant in that it suggests we need to look beyond the state, MNCs, and civil society to include the role that institutions and regimes play in shaping global politics.

Figure 1-6: https://www.flickr.com/photos/thomashawk/26307220853 Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Thomas Hawk.

Finally, the concept of structuralism also contests the traditional state-centric view of global politics. Structuralism argues that global politics is not about states competing with each other to achieve the national interest. Instead, structuralists offer a critical perspective on global politics, arguing structures of wealth and privilege define it. There are a few different variants here. The neo-Marxist variant argues global politics is defined by class conflict with states simply being the pawns of the rich and the powerful. This globally dominant class uses the economic, political, and military machinery of the state to pursue their interests. Other variants suggest that patriarchal structures and ethnic structures define the form and function of global politics. Importantly, these structuralist approaches suggest that global politics is shaped by the interests of the privileged and the wealthy and that states, regimes, and institutions are a simply means for them to do so. In subsequent modules, we will unpack the tensions introduced in this section to build our toolbox for explaining and understanding global politics.

- How is the study of global politics contested?

- What are the two basic positions on global politics outlined in the text and this module?

- How do the concepts of sovereignty, anarchy, complex interdependence, and structuralism contribute to these two positions?

- Which position do you find most persuasive and why?

Figure 1-7: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/idea-world-pen-eraser-paper-1880978/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of qimono.

For many students, ‘theory’ is a dirty word. Why would we want to study the writing of people long dead? What could Thucydides or Hobbes or Marx possibly know about the world we live in today? If you were to hand a smartphone to any of these men, they would likely think you were the devil himself. However, this a misunderstanding of theory. The most basic definition of theory is to think deeply, to reflect on problems, to understand why something is happening or how something is happening, and perhaps even what to do about it. By this definition, most students are using theory all the time even if they do not know it.

Theories are important because they allow us to answer questions that cannot be easily answered. They provide some guidance as to what is important in a given situation. They suggest some means to respond to the problems we face. The most interesting questions that theories seek to answer are those that are counter-intuitive – those things that do not make sense or cannot be answered by common sense. For example, to borrow from our reading, we don’t ask why someone runs out of a burning building. That is common sense. But why would someone run into a burning building? There isn’t a commonsense answer here. In global politics, an example of a counter-intuitive question might be why people volunteer to fight in wars that are not in defence of their own country? More specifically, in social science there three basic types of questions that theories try to answer. They try to answer explanatory questions that seek to explain why something happens. For example, what are the causes of war? They try to answer normative questions that argue what should happen. For example, should Canada undertake peacekeeping missions? They try to answer interpretative questions that seek to understand events or processes. For example, why did Al Qaeda fly two airplanes into the Twin Towers on September 11th, 2001?

Figure 1-8: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:No-nb_bldsa_5c006.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of A. Frank.

In order to build our theoretical toolbox for the study of global politics, we need to understand the history of the discipline. Until the early twentieth century, the study of global politics was deeply entwined with the study of philosophy, history, economics, and diplomacy. It was not treated as an independent discipline. For example, the study of war was a matter of history. For example, why did the Napoleonic Wars happen? Or it was a matter of diplomacy/strategy, for example, Clausewitz’s dictum that “war is merely the continuation of politics by other means.” However, World War One changed everything. The ‘War to End All Wars’ was like no other that had preceded it. It was a total war that rallied all the state’s resources, including bringing women out of the house and into the factories and hospitals. It shifted the balance of power from Europe to the US and was witness to the Russian Revolution and the emergence of Communism. There was new technology like the use of airplanes and the first aerial bombings, U-boat submarines, tanks, poison gas, and machine-gun protected tranches. However, most importantly, 9 million soldiers and 12 million civilians died. Over 21 million military men were left wounded, with missing legs and arms. Countless others were left psychologically damaged by witnessing the atrocities of modern war. For those studying global politics, it was no longer possible to condone Clausewitz’s dictum. It was no longer possible to just understand the history of why a particular war happened. An answer to the carnage was demanded. In response, new institutions were created, like the League of Nations. And the discipline of International Relations was founded in Aberystwyth, Wales, with the creation of the Woodrow Wilson Chair in International Relations. Its mission was to search for “the foundation of a lasting security, a lasting prosperity, and a lasting peace.” It was to use rationality and reason to banish the scourge of war.

Figure 1-9: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jannes_shootings/31711948134/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Janne Räkköläinen.

From the foundation of the discipline in 1919, International Relations has undergone a series of four Great Debates. Although, it should be noted these ‘Great Debates’ are better understood as a heuristic to understand the discipline of IR than actual historical debates. They represent the main points of contention in the field. The First Great Debate was between Realism and Idealism in the 1930s and 40s. The Idealists sought to transform global politics through the application of rationality and reason. They sought to construct new institutions like the League of Nations, which enshrined ideas like collective security. The Realist was critical of such attempts. They argued the Idealists were viewing the world the way they wanted it to be and not how the world actually was. Moreover, Realists argued ignoring the way the world really works was dangerous since it left the world unprepared to deal with states that didn’t find the new rules to be in their interests.

Figure 1-10: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/lab-science-scientific-chemistry-512503/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of holdentrils.

The Second Great Debate was in response to the behavioural turn in the social sciences in the 1950s and 60s. It is sometimes referred to as a debate between traditionalism and behaviouralism. The early IR scholars were predominantly classicists or traditionalists that looked to history and interpretation to understand global politics. By understanding global politics, they argued it was possible to have a holistic view of the world and be able to adapt to the ever-shifting context of global issues. Moreover, they argued the sheer openness and unpredictability of global politics made anything more a fool’s errand. The behaviouralists argued that the study of global politics had to be more scientific, adopting the methods of the natural sciences. This meant that the behaviouralists were positivists and believed that the study of global politics should be based on observation, hypotheses building, and identifying causality through empirical testing.

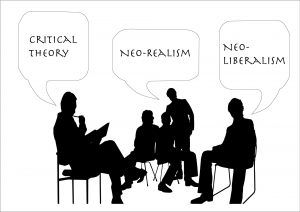

Figure 1-11: Permission: Courtesy of the Distance Education Unit (DEU), University of Saskatchewan, based on https://pixabay.com/illustrations/exchange-of-ideas-debate-discussion-222788/

The Third Great Debate was the inter-paradigm in the 1980s and 90s. For some, this was a debate between the Neo-Realists and the Neo-Liberals and is therefore also called the neo-neo debate. For others, the debate also included more critical and predominantly Marxist approaches to IR. We will be discussing the specifics of these theories in subsequent modules and won’t be covering it here. However, the inter-paradigm debate is important in understanding the development of the study of global politics. The Neo-Realism of Kenneth Waltz was the dominant theory at the time. It privileged the state, anarchy, the role of power, and high politics in explaining global politics – essentially the state-based view of global politics introduced earlier in the module. Neo-liberalism conceded some of these points by arguing that the state was a privileged actor and that anarchy was the logic of the international system. But Neo-Liberalism argued that despite this, global politics was a lot more complicated than the Neo-Realists view. There were more actors, more structures, and more potential for cooperation. The critical perspectives also pushed back against the Neo-Realists, suggesting there were more deeply embedded structures that played a causal role, such as class and gender.

The Fourth Great Debate was between rationalism and reflectivism. This is the most inward focused debate, contesting the epistemology of IR – or how we know what we know about global politics. On the one side of the debate is rationalism, which argues the study of global politics must be rational, empirical, and positivist. We must observe the world the way it is, measure it, explain it, and with that knowledge, make effective policy. The rationalist camp includes the mainstream theories of global politics that seek to problem solve without changing or challenging the system as it is. On the other side of the debate is reflectivism, which seeks to challenge the structure of global politics itself. The reflectivist camp includes the alternative theories such as post-structuralism, feminism, thick constructivism, and critical theory. These theories will be introduced in detail in subsequent modules. But they all oppose the mainstream or problem-solving theories. The main point of contention comes back to that epistemological debate. Rationalists argue we can only know what we can observe and measure. Reflectivists argue it is the underlying ideas that shape both the practice and, perhaps more importantly, the theory of global politics. These four Great Debates frame the main points of contention in the study of global politics.

Importance and Impact

As we begin to approach the different theories and tools that explain/understand global politics, it is important to keep the above discussion in mind. First, through the evolution of IR as a discipline and the four Great Debates, no theories have been falsified. They may wax and wane in terms of importance in the discipline, but they all still have their advocates. So, where does that leave us? It brings us back to the point introduced earlier – we need to build a toolbox of different theories to apply to different questions and issues. This is pluralism, the argument that there are not one consistent means to discover ‘truth’ in global politics but rather many. As students of global politics, we need to know which tool to apply to which problem and when.

Second, it is important to recognize two basic types of theory. The first type includes the mainstream theories or status-quo theories. These theories tend towards positivism, empiricism, and rationality. They take the world as it is and do not question the essential nature of the system. With the nature of the world taken as a given, these theories seek to solve problems without challenging hierarchies, history, or the status quo. The second type includes revisionist theories. They tend to think outside the box, or even to question the box itself. They ask questions about why the system is the way it is. They ask questions of power and how it shapes the system. In so doing, they are seeking to change the system to achieve progress by making it more equitable and/or more just. The status quo theories argue the revisionist camp is both foolish and dangerous. They argue we can not make the world the way we might want it to be. The revisionists argue that the status quo camp is at best lacking the imagination to make the world better or, at worst, they represent and are acting in the name of the powerful that benefit from it as it stands.

- What is theory?

- What defines the theories of global politics?

- What are the four Great Debates?

- What is the value of these debates in understanding global politics?

- Do you find the status quo or revisionist camp more persuasive?

The primary purpose of this module was to establish a basic framework for the rest of the course to build on. We began by seeking some conceptual clarity. First, what defines global politics? We noted two contested definitions. On the one side, global politics is the study of a state-based world composed of thick borders and the national interest. On the other side, global politics is more complicated. It is a world where borders are not so thick nor so meaningful. The number of actors involved is much greater, and the issues more diverse. To understand the debate between these two positions, we introduced some of the contested concepts with the discipline. We introduced the concept of sovereignty, defined as someone or something that has supreme authority in a clearly delineated territory. We traced the evolution of sovereignty from being invested in the person, in the state, and more controversially in the citizenry. We introduced the flipside of state sovereignty as the condition of anarchy. Anarchy is defined as a system with no overarching authority. We introduced the concept of complex interdependence that challenges the state-based model of global politics to suggest the world is a more complicated and contested place and that this complexity is being managed through international regimes and institutions. We introduced the concept of structuralism which applies a more critical eye to global politics. It suggests that there are underlying structures of privilege and power that explain the logic of global politics.

We concluded the module with the argument that these contested concepts are the building blocks of our theories of global politics. These theories of global politics have evolved since the inception of the academic discipline in 1919 through Four Great debates: idealism/realism, traditionalism/behaviouralism, the inter-paradigm debate, and rationalism/reflectivism. These debates reflect the key debates in the field. Do we treat the world as it is or as it should be? Do we interpret the world or do we measure it? Do we seek to solve problems within the structure of global politics as it is or do we question the structure itself? All of these questions have important implications for understanding/explaining global politics. All of these questions have important implications for how we act in the world. We will use the framework introduced in this module as well as the questions it raises to explore the content for the rest of this course.

Review Questions

Glossary

Anarchy: Lack of an overarching authority in a given system

Complex Interdependence: Argues international relatiosn is constituted by a wide variety of actors who work to form international regimes ti coordinate and cooperate on global issues

First Great Debate: A Great Debate within International Relations in the 1930s and 40s, between Realism and Idealism. The Idealists sought to overcome global issues through transforming global politics. The Realists argued this was naïve at best and that for peace and prosperity, it was imperative to treat the world as it was not as we wanted it to be

Fourth Great Debate: A Great Debate within international relations, between rationalism and reflectivism began in 1988. Rationalism adopts a positivist view of global politics, arguing for a scientific approach. Reflectivists argued for a post-postitivist approach to global politics, adopting a critical approach.

Global Politics: The sum total of the economic, political, diplomatic, military, and social relationsat work above, between states.

National Interest: The interests, goals, and objectives of the state as articulated and pursued by the political leadership.

Politics: Social relations regarding power and authority in a particular community – or who gets what, when, and how

Second Great Debate: A Great Debate within international relations, between traditionalism and behaviouralism, took place over the 1950s and 1960s. Traditionalists argued for a holisitic and historical approach to the study of global politics, arguing the system was too open for scientific rigidity. Behviouralism argued for a more empirical and scientific approach to global politics in order to generate falsifiable causal arguments and prescriptions

Sovereignty: the assertion that someone or something is the supreme authority within a clearly delineated territory

Structuralism: suggests that underlying structures of privilege and power explain the logic of global politics.Examples of strutcures include economic class, ethnicity, and gender.

Theory: A set of ideas, applied to make sense of events, processes, or outcomes. At the most basic level, theory allows us to think deeply, to reflect on problems, to understand why something is happening or how something is happening, and perhaps even what to do about it

Third Great Debate: A Great Debate within international relations, known as the interparadigm debate or the Neo-Neo debate, that took place over the 1980s and 1990s. The Neo-Neo Debate was between Neo-Realism and Neo-Libealism – both agreed on the basic points of a state based, anarchical world, constituted by sovereign states. The Neo-Realists argued this resulted in a competitive world dominated by power and security seeking behaviour. The Neo-Liberals conceded the nature of global politics but argued the world was more cooperative.

References

Clausewitz, Carl Von, and Rapoport, Anatol. On War. Penguin Classics. Harmondsworth, Eng. ; New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books, 1982.

“History - Department Of International Politics". Aberystwyth University, 2020. https://www.aber.ac.uk/en/interpol/about/history/.

Lasswell, Harold D., and Abraham Kaplan. 1950. Power and society: a framework for political inquiry. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Myers, Joe. "How Do The World's Biggest Companies Compare To The Biggest Economies?". World Economic Forum, 2016. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/10/corporations-not-countries-dominate-the-list-of-the-world-s-biggest-economic-entities/.

“National Interest - Oxford Reference". Oxford Reference, 2020. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100224268

“Politics - Oxford Reference". Oxford Reference, 2020. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.2011080310033458

“The Human Toll Of The War 'To End All Wars'". National Public Radio, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2011/08/11/138823855/the-human-toll-of-the-war-to-end-all-wars

Supplementary Resources

- Carlsnaes, Walter., Risse, Thomas, and Simmons, Beth A. Handbook of International Relations. 2nd ed. London: SAGE, 2013.

- Griffiths, Martin. Rethinking International Relations Theory. Rethinking World Politics. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

- Marks, Michael P. Metaphors in International Relations Theory. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.