- Define International Governmental Organizations

- Explain the role of IGOs in global politics

- Define International Law

- Explain the role of International Law in Global Politics

- Describe how different theories and approaches to global politics make sense of IGOs and International Law

Traisbach, Knut. “International Law”, in International Relations. Bristol: E-International Relations, 2017.

- International Governmental Organizations

- Supranational Authority

- Intergovernmental Organization

- Collective Action Problem

- Epistemic Community

- International Law

- Law of Peace

- Law of War

- Treaties

- Customs

- General Principles of Law

- Legal Scholarship

- Pacta Sunt Servanda

- Odious Debt

Learning Material

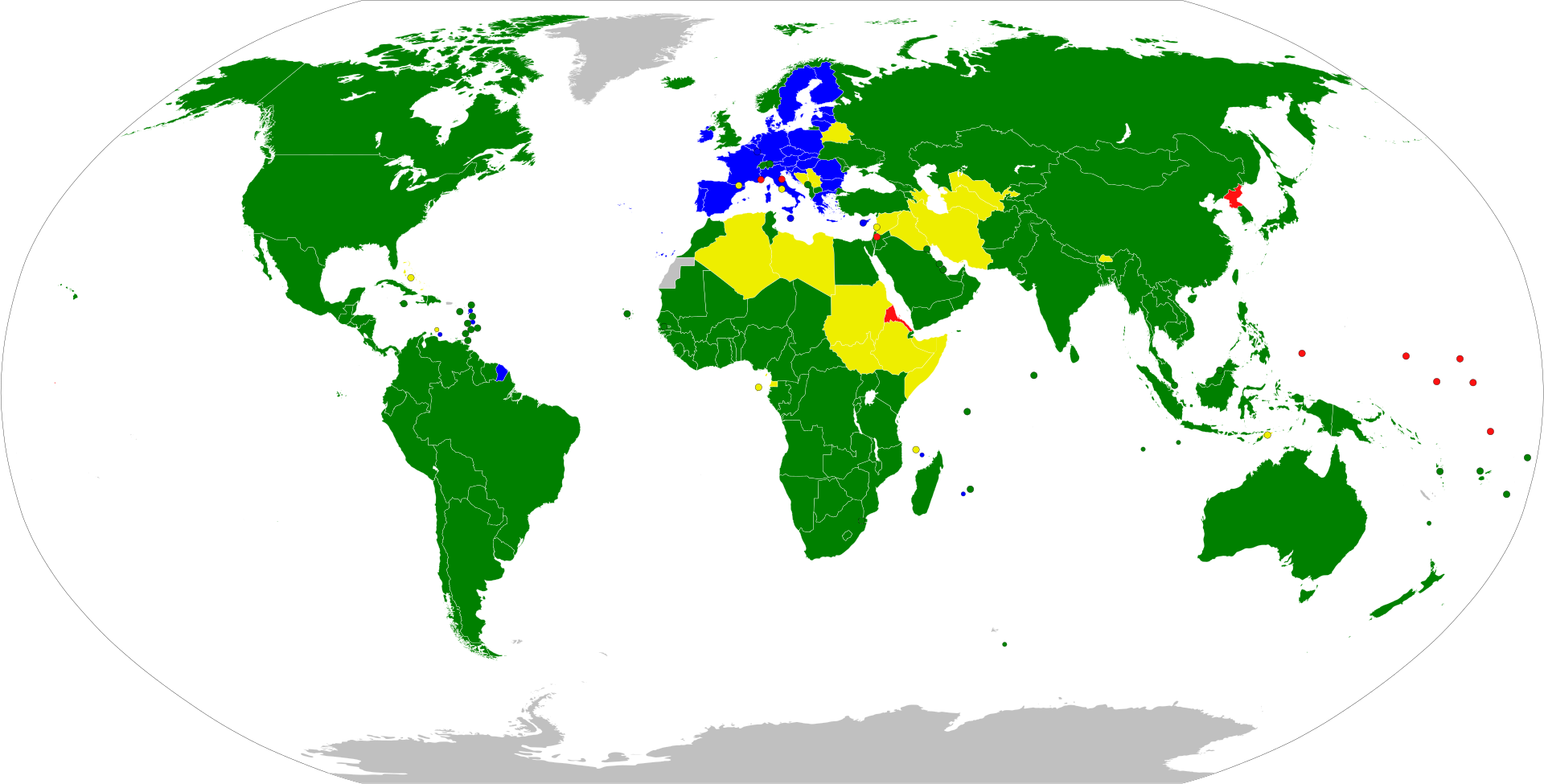

Figure 10-2: Map of World Trade Organization members and observers. (green) Members – (blue) Members, dually represented by the European Union (yellow) Observers (red) Non-members. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WTO_members_and_observers.svg#/media/File:WTO_members_and_observers.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Happenstance et al.

In order to understand IGOs in global politics, we need to define them and look at what they do. The most basic definition of an IGO is an organization created by three or more states with some form of permanency and that meets regularly. Depending on the definition, there are more than 5,000 IGOs today, which exponentially greater than in 1945. Some IGOs are quite small, like OPEC, a 14 state global energy cartel. Others are quite large, even near-universal, like the UN, with 193 member states. Often IGOs emerge out of less formal arrangements, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, which emerged out of a united opposition to the Soviet Union. Another example, which we introduced in the IPE module, is the WTO which emerged from the GATT agreement. The GATT was not an IGO in that it was an agreement with a small secretariat and lacked the agency to make political decisions. The WTO, on the other hand, is a large and formal institution with much more agency to expand trade in goods and services, monitor compliance with agreements, and settle disputes. Other IGOs are more novel, like the League of Nations and the United Nations. But even then, the UN was created from the foundations of the League of Nations. And the League of Nations was created from the normative influence of 19th-century peace societies. However, a defining characteristic of all IGOs: states and only states are members. They may offer informal membership or observer status to other actors, but only states are full members, which often comes with voting rights and leadership roles.

Figure 10-3: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/america-earth-flags-flag-global-1313553/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

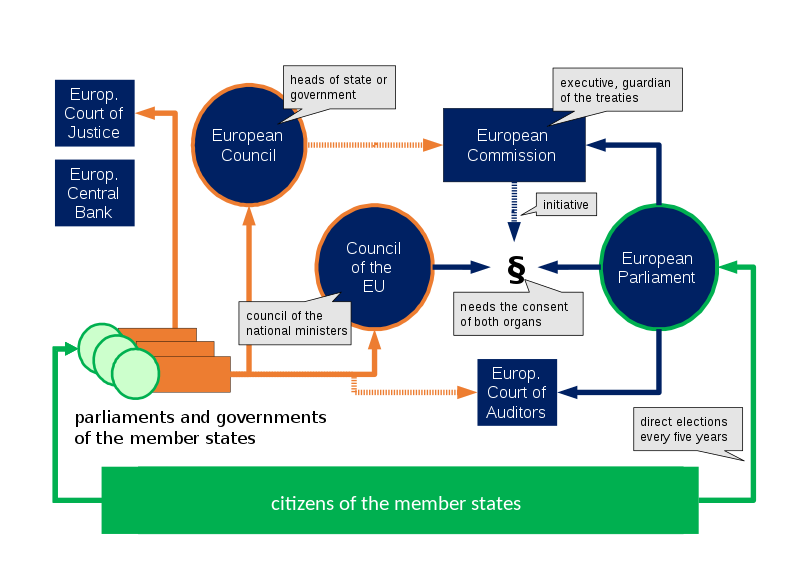

IGOs perform a variety of roles in global politics. Some IGOs have a very expansive role, such as the European Union. The EU is a regional organization that mixes supranational and intergovernmental properties. In areas where the EU has the ability to act without consulting member states, it has supranational authority. While it is true that this authority was delegated to the EU institutions by the member states, it now has state-like powers that supersede national authority. Examples of where the EU has supranational authority include trade policy, competition policy, and Euro states’ monetary policy. In areas where the EU does not have exclusive competency, they either have shared competencies with member states or have a supporting role for member state competencies. Shared competencies mean that member states can enact legislation as long as the EU has not already put regulations in place. Examples of shared competencies include social policy, environmental policy, and energy policy. Supporting competencies mean that member states have exclusive jurisdiction, but the EU institutions play a role in coordinating policies between member states. Examples of supporting competencies include health policy, education policy, and civil protection. The EU is an interesting case for the study of IGOs and global politics in that it is a novel form of political organization. It challenges the privileged position of the sovereign state by providing EU institutions supranational authority. And it brings a technical approach to solving problems like climate change and trade policy.

Figure 10-4: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Organs_of_the_European_Union.svg#/media/File:Organs_of_the_European_Union.svg] Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Ziko van Dijk.

Other IGOs are very narrowly focused and clearly intergovernmental organizations. For example, the International Telegraph Union was founded in 1865 and evolved into the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in 1947 as a UN specialized agency. The ITU is not in any way supranational but rather looks to solve concrete problems and coordinate policy between member states to avoid problems. More specifically, the ITU works in four sectors. First, in Radio Communication, the ITU seeks to coordinate the radio-frequency spectrum and satellite orbits. Second, the ITU works to set and coordinate standards on global telecommunications. Third, the ITU undertakes development projects to provide more equitable access to Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). Finally, the ITU regularly brings the ICT community together to disseminate knowledge and best practices. The ITU is an example of a very narrowly defined IGO.

In between the EU and the ITU are a wide variety of IGOs, but they are all created by states, and they all touch on one or more of the following themes. First, and most circumscribed, IGOs can promote the interests of their member states. For example, the BRICS organization was established by its founding members, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, to provide a counterweight to the IFIs dominated by the US and European states. OPEC is another such example. These IGOs are vehicles for states to enact agency in global politics.

Figure 10-5: Monument to the International Telegraph Union in Bern Switzerland. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ITU_monument,_Bern.jpg#/media/File:ITU_monument,_Bern.jpg Permission; CC BY-SA 3.0

Second, many IGOs seek to find or facilitate solutions to common problems. Such IGOs often address the collective action problem in global politics. A collective action problem is when all actors would be better off cooperating together, but individual members are better off by defecting and pursuing their own narrowly defined self-interest. The classic example is the ‘tragedy of the commons’. In this case, a collective resource like pasture land is available to all the surrounding farms. There is a collective interest in maintaining the health of this shared resource. But there is an individual interest in over-using the shared resource to save their own resources. This brings the collective interest into tension with the individual interest. IGOs can seek to bridge this divide. They bring stakeholders together, facilitate an agreement to achieve the collective good, monitor compliance, and possibly sanction breaches to the agreement. For example, the UN Environment Programme works to support the Montreal Protocol (1987), perhaps the most successful environmental program to date. The Montreal Protocol is a multilateral framework to address Ozone depletion. It has evolved over time, starting with a ban on Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) to now include over 100 man-made ozone-depleting substances (ODS). It has also evolved from the twenty original state parties to now include all 193 UN member states. It is a collective action problem in that protecting the environmental commons is in everyone’s interest. However, individual states have an incentive to continue using ODS for economic reasons. The Montreal Protocol solves the collective action problem by negotiating binding agreements to ban ODS, controlling the trade in ODS, monitoring compliance with the agreement, providing funds to economically developing states, and putting in place procedures to facilitate compliance. However, not all IGO initiatives have been as successful. For example, IGOs, like the UN, have repeatedly failed to secure universal human rights and to ban the scourge of war. The list of failures is legion, including recent failures in the Syrian Civil War, Myanmar’s treatment of the Rohingya and the recent military coup, and the Chinese persecution of the Uighurs. Yet, there is some room for optimism. We will discuss this at the end of this section.

Figure 10-6: Source: https://flic.kr/p/d81hd3 Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Christiaan Triebert.

Third, IGOs provide a platform to bring together experts on a topic to facilitate the production and dissemination of knowledge, particularly on global issues. A pool of experts and practitioners in a particular field is called an epistemic community. IGOs create epistemic communities on a very wide variety of issues, including trade, development, the environment, technology, refugees, health, and nuclear energy, to name just a few. These epistemic communities work together to bring together research, best practices, and possible policy recommendations for actors to consider. For example, the World Health Programme (WHO) has played an important role in pooling knowledge and sharing best practices in the COVID 19 pandemic. The WTO provides members access to granular information on global trade patterns and trajectories in economic conditions. A variety of IGOs provide statistics and data to both members and the general public, including the UN Statistics Division, the IMF, the World Bank, and the OECD. All of these bodies and their associated epistemic communities provide platforms for actors to address global issues.

Figure 10-7: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/unitednationsdevelopmentprogramme/35060320606/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of United Nations Development Programme.

However, despite the proliferation of IGOs, there is still the question of efficacy. The rise of IGOs following World War Two created some hope that they would overcome hegemonic stability problems. Hegemonic stability theory suggests that there needs to be some actor or group of actors powerful enough and willing to use that power to create and maintain global order in an anarchical world. Some argue that IGOs can provide that connective tissue to maintain global order even when the hegemonic force erodes. IGOs have had significant achievements, and the Montreal Protocol is an example of a solid win. However, IGOs have also encountered significant obstacles, especially recently. These obstacles include a lack of consensus on the rules and objectives of the international economic, political, and normative orders. New regional powers and the rise of China as an economic Great Power are challenging the Western-dominated IFIs. They are challenging the norms of good governance, sustainable development, and liberal economic practices that are often attached to development aid by Western states and the IFIs. The international political order is eroding under both a retreat of the US and the rise of revisionist powers like China, Russia, and regional powers. This has been clearly demonstrated by the UN Security Council’s failure to fulfill its mandate to maintain international peace and security, despite having the legal means to do so. However, most importantly, the normative basis of the international order is unravelling. The post-war international order is a Western creation. It is based on Western norms. This order and these norms are being challenged by new powers, revisionist powers, revanchist powers, post-colonial states, as well as MNCs and NGOs. Cumulatively, this has led to a perception that IGOs are ineffective.

However, the biggest obstacle to IGO effectiveness is the growing gap between rhetoric and practice. The IFIs say they are trying to achieve meaningful and sustainable development, but their SAPs have led to massive dislocation in emerging and post-colonial economies. The UN Security Council is tasked with maintaining international peace and security, but it has been manifestly unable to deal with tragedies in Rwanda, Syria, Myanmar, and China. Even the EU declares it is keeping universal human rights at the core of its policymaking, but the 2015 Syrian refugee crisis has fractured EU member state unity and led to numerous human rights violations. But there is some hope. If we think of IGOs less as government and more as functional and norm-building bodies, our expectations will be more realistic, and the successes will be more evident. IGOs have had tremendous success in functional objectives, for example, repairing the ozone layer, coordinating flight paths, radio frequencies, and the internet. IGOs have been instrumental in dealing with humanitarian tragedies, from the World Food Programme to coordinating disaster relief. And finally, IGOs have played a crucial role in establishing normative standards, even if they are not always honoured. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights may not be binding, but it is used to shame states that violate it. The Universal Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples may be considered aspirational by many governments, but it has shaped practices, as we have seen in Canada. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women or the Convention on the Rights of the Child may be routinely violated. That is not to say these agreements are fully honoured, but they provide a normative standard by which groups can challenge state practices, and some have successfully done so. This may seem like a shallow or even phyric victory, but it is possible to see the long shadow of progress when put into historical context. These normative standards do affect global politics, albeit often too late for far too many.

Figure 10-8: Source: https://flic.kr/p/k382X4 Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of UNAMID.

International law and IGOs are deeply connected. International law is a product of diplomacy, treaties, and agreements that seeks to address functional problems and build on established norms that set expectations of conduct in global affairs. At a practical level, IGOs have increasingly provided the platforms through which international law is introduced, negotiated, and monitored. At a more theoretical level, both IGOs and international law seek to bring a degree of stability and order to an anarchical global system. Currently, international law is at play in almost everything you do, even if you are unaware that you are doing so. When you use your cell phone, take a flight, shop online, listen to the radio, log on to the internet, or buy any good that is part of the global supply, you have engaged with the myriad of agreements, treaties, and norms that constitute international law. At a more visible level, international law plays out in international economics, like the WTO agreements and dispute settlement, and in humanitarian crises, like the Rwandan genocide and the subsequent adoption of R2P. In order to understand the connection between international law and its impact on global politics, we need to define it and trace its evolution. More specifically, we will be looking at public international law versus private international law. Private international law is mostly concerned with disputes between individuals and businesses where more than one legal system may be applicable. Public international law is concerned with the relationship between states and the rules that are binding on all states in the international community.

Within the broad category of public international law, there are distinct subfields, including the law of peace and the law of war. The law of peace deals with how states interact with each other, including treaties, diplomacy, state responsibility, international economics, the law of the sea, the environment, and space. We touched on the law of war when discussing Just War Theory. Most contemporary debates on the law of war fall into the area of international humanitarian law. International humanitarian law seeks to regulate the conduct of war, protect categories of people, and prohibit particular weapons deemed inhumane or indiscriminate, such as chemical and biological weapons or landmines. More recently, international human rights law and international criminal law have bridged the separation between the laws of peace and the laws of war. This has been most notable in the International War Crime Tribunals and the establishment of the International Criminal Court in the Hague.

Figure 10-9: Arms Control Statue Outside of the UN. Source: https://flic.kr/p/FnxtY Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Jim Bowen.

However, one of the main problems with defining international ‘law’ is the word law. When most people hear the word ‘law’, they think of domestic law. Domestic law is a body of rules that govern society, enforced by a centralized authority. These rules derive from the legislative branch of government. They are applied and enforced by the executive branch of government. And the judicial branch sanctions non-compliance with financial penalties or incarceration. International law is a pale comparison of domestic law. There is no world government that has the legitimate authority to legislate, apply, and enforce international law. Instead, public international law seeks to order relations between states. It does so by establishing a body of rules that govern the relations between states and the general conduct expected of states.

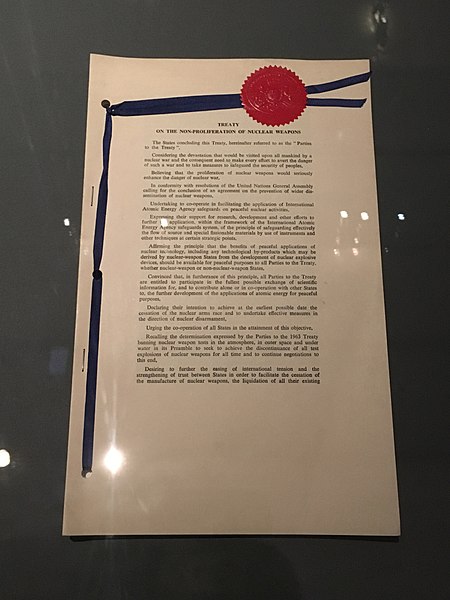

The body of rules in public international law is derived from treaties, customs, general principles of law, and legal scholarship. Treaties are written conventions between states that establish rules or set limits on behaviour in a particular issue area. For example, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT, 1970) bans non-nuclear-weapon states from pursuing a nuclear weapons program and prohibits the five recognized nuclear power states from assisting any other state in doing so. Further, it requires all existing nuclear weapon signatories to commit to disarmament. Importantly, based on pacta sunt servanda, treaties remain intact even when the government changes. For example, the USSR signed the NPT, but Russia is still expected to fulfill the treaty’s obligations. If a state breaches its treaty obligations, it may be sanctioned. These sanctions start with naming-and-shaming, move to economic sanctions, and ultimately may result in military force. However, the form and function of sanctions ultimately depend on the text of the treaty, the power of the states involved, the degree of opposition to the breach, and someone’s willingness to do something about it. This is because there is no legitimate overarching authority to apply and enforce international law. We will return to the issues of compliance and enforcement at the end of this section.

Figure 10-10: Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1968_TNP_NPT.jpg#/media/File:1968_TNP_NPT.jpgPermission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Marc Baronnet.

Custom is a traditional source of public international law that treaties often draw upon. Custom is defined as generally accepted practices. If enough people do something regularly enough and long enough, it takes on the status of law. Historically, custom was the most important source of international. However, it is now generally accepted that the treaty shall take precedence if treaty law and customs clash. Importantly, if custom is accepted as international law, it is generally binding on all states. For example, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) deals with issues of defining territorial waters, fishing rights, navigation, marine pollution, and other environmental issues. It is largely a codification of customary international law. Therefore, while the US is not a signatory to UNCLOS, it recognizes most of the provisions as reflective of customary international law.

General principles of law are also an important source of public international law. Something is considered a general principle of law if it is recognized in most legal systems. For example, most legal systems recognize reparation for caused damage, rules for interpretation, or the general means for conflict resolution. General principles of law are generally used to fill gaps in international law. For example, when discussing the NPT above, Russia was still expected to uphold the provisions of the treaty even though it was negotiated and ratified by the USSR. This is because of pacta sunt servanda, which means ‘agreements must be kept’, and is a principle is derived from a general principle of law.

Finally, and subsidiary to the first three sources of international law is legal scholarship. Legal scholarship encompasses the written arguments of the most prestigious and respected legal scholars.

This discussion of public international law gives a perception of a solid jurisprudence and of a world increasingly brought under the rule of law. However, this comes back to an issue highlighted earlier – the application and enforcement of public international law. The issue of enforcement is a perennial issue in international law, but it is a problem that seems to be getting more pronounced. A brief look at the 21st century highlights serious breaches of international law that went unchecked: American invasion of Iraq (2001), the Darfur conflict in Sudan (2003), the Syrian Civil War (2011+), Yemeni Civil War (2011+), Russian annexation of Crimea (2014), the Rohingya Crisis in Myanmar (2017+), the Uighur Crisis in China (2017+), the Myanmar Coup (2021). All of these events have significant breaches of public international law and, more specifically, international human rights law. As the world watches, nothing is done beyond rhetorical condemnation, leading to a growing perception that international law is ineffective despite past declarations of ‘never again’, most notably after the Holocaust and the Rwandan Genocide. Yet, at the same time, it is important to note that most states at most times adhere to international norms, rules, and laws. How do we bridge this paradox between egregious breaches of international law and the propensity of most states at most times to adhere to it? One way to reconcile this paradox is to disabuse ourselves of the notion that international law is, in fact, ‘law’. If, instead, we understand international law as fundamentally a political exercise intended to generate a stable and predictable international order based on shared norms, things make more sense. This approach explains periods of relative stability based on a general acceptance of global norms. During such periods, states are able to coordinate on functional issues that arise, and may even be able to address more normative issues. It also explains volatile periods when norms break down and states, especially Great Powers, disregard international law with increasing impunity. Fundamentally, this approach views international law as an exercise in norm building, collapse, and rebuilding. While there is a degree of pessimism in this view, there is also a note of optimism. The degree to which most states at most times adhere to international law speaks to its perceived value: it is in the interest of states to build an orderly world. This brings us back to IGOs, the most notable means to build shared norms, negotiate treaties, and codify international law.

Figure 10-11:

The International Criminal Court Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:International_Criminal_Court_building_(2019)_in_The_Hague_01.jpg#/media/File:International_Criminal_Court_building_(2019)_in_The_Hague_01.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of OSeveno.

Figure 10-12: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_Seal_Team_is_coming_out_of_water.jpg#/media/File:A_Seal_Team_is_coming_out_of_water.jpgPermission: Public Domain.

In stark contrast to Realism, IGOs and international law are very much at home with Liberalism. Liberalism argues that we can overcome the threats posed by an anarchical system. We can do so by privileging individual rights, enhancing economic prosperity through trade, and building institutions to address common threats. More specifically, Liberals highly approve of IGOs. In fact, the first universal body dedicated to global governance, the League of Nations, was a Liberal project. The Bretton Woods System was a Liberal project. At the end of the Cold War, Liberal Internationalists pursued an aggressive human rights regime, including institutions like the International Criminal Court, policies like the Responsibility to Protect, and conventions like the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Liberals see IGOs as a means to coordinate solutions to functional issues and a means to cooperate on political issues. They see IGOs as a means to lower the costs of cooperation and raise the cost of conflict, whether this is economic, like the Bretton Woods System, or political, like the ICC and the UNSC. In a similar vein, Liberals argue international law is an important tool in achieving progress in global politics. They recognize that international law is ‘soft’ since there is no world government to legislate, apply, and enforce it. However, Liberals do argue that international norms, regimes, treaties, and law have force. They shape how actors behave. They shape actors’ interests. International law is an essentially political process by which states can negotiate agreements, regulate international conduct, and set standards of appropriate behaviour. Moreover, Liberals see an intimate connection between international law and IGOs. They argue IGOs facilitate a process of building norms, regimes, and eventually international law. For example, the League of Nations and the United Nations have been instrumental in pursuing human rights norms, regimes, and international law. One important result has been the International Criminal Court, an IGO which prosecutes individuals who perpetrate the international crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression.

Figure 10-13: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Omar_al-Bashir,_12th_AU_Summit,_090131-N-0506A-347.jpg#/media/File:Omar_al-Bashir,_12th_AU_Summit,_090131-N-0506A-347.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jesse B. Anwalt.

Constructivists posit a very different view of IGOs and international law. Realists argue they do not constrain state sovereignty but rather represent the interests of powerful states. Liberals see them as a via medium for states to address global issues and foster greater interdependence between states. In contrast, Constructivists see IGOs and international law as shaping global politics by transforming identities and framing expectations of behaviour. States may create IGOs, but once constituted, they develop their own identity. They develop their own vision of the world. It may not be radically different from that of its founding states, but over time, as they work on specific issues, IGOs can stray from their member states’ original mission. For example, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees was established in 1950 to help Europeans dislocated from World War Two get home. It was expected to operate for three years. However, the UNHCR argued that refugees are a persistent and global problem. The UNHCR evolved into the UN Refugee Agency. It has defined the legal meaning of a refugee, fought for refugee rights, and been on the front lines of refugee crises around the world. Significantly, for Constructivists, the UNHCR has developed its own identity and framed its own interests. The UNHCR has engaged in social discourse with states and institutions to frame the definition of a ‘refugee’. As a result, actors’ identities have changed, interests redefined, and practices shifted. Similarly, Constructivists see international law as a deeply political process that connects identity, interests, and practices. Therefore, international law is a social construction that evolves through communication to establish intersubjective meaning. The UNHCR is again a useful example. The UNHCR established a dialogue on what it means to be a refugee and on the responsibility of the international community to refugees. This dialogue shaped identities, interests, and practices, leading to international law: the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, the 1954 Convention on Stateless Persons, and the 1967 Protocols.

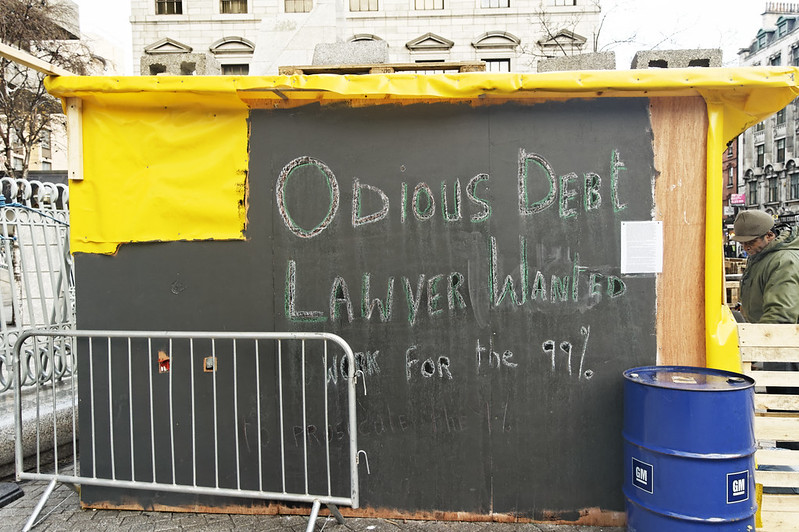

Critical and Post-Structural approaches to global politics see IGOs and international law as structures that work in the interest of the powerful and to the detriment of the weak. Critical approaches share a distrust of IGOs. Marxists view IGOs as furthering global capitalism, economically through the IFIs and politically through the UN organs and specialized agencies. For example, the IFIs attached market-based SAPs to loans in the 1970s and 80s to the benefit of the international economic system and Western lenders but to the detriment of borrowers in the majority world. Politically, UN agencies like the UNCTAD have framed unfettered global capitalism as the only path to development, contrary to the results. Critical Feminism and Environmentalism see IGOs as maintaining systems of patriarchy and environmental exploitation, respectively. Post-structural approaches to IGOs highlight their role in justifying and reifying existing economic, political, and ideational discourses. In purporting to foster development, the IFIs have ‘helped’ post-colonial and emerging economies. But in reality, this ‘help’ has reinforced existing discourses of Western superiority and undermined subjugated discourses that may be more appropriate or more effective in achieving goals defined by states in the majority world. Critical approaches and Post-Structural approaches come together, to a degree, in critical legal studies. Critical legal studies unpack international law and expose incoherency in its liberal bias. They argue that international law is built upon two theoretical streams, liberal ideology and public international legal argument. Liberal ideology legitimates and reifies the sovereign state system, limiting more emancipatory discourses to the detriment of the majority world. Public international legal argument is situated in a Eurocentric tradition that excludes the majority world’s history and lived experiences. Finally, critical legal studies questions the self-proclaimed objectivity of international law, which stipulates that law has a single meaning and application. They instead argue that international law can have different meanings in different contexts, all of which must be unpacked and explored. In so doing, alternative and subjugated discourses can be identified and applied to achieve more equitable outcomes. For example, critical legal scholars have advocated on the issue of odious debt. As introduced earlier, the principle of pacta sunt servanda argues that states must fulfill their obligations even if the government changes. However, consider an authoritarian state that borrowed large sums of money to persecute their own people and embezzle money for personal gain. If that government is overthrown, should the new government have to pay back that debt used to persecute them? Critical legal scholars suggest this is an odious debt and should not be expected to be repaid. It is even more odious when the lenders knew the borrower’s authoritarian nature and the history of coercion against their citizens. Critical legal scholars argue that such lenders are also culpable and should take responsibility for this odious debt.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Collective Action Problem: a situation where all actors would be better off cooperating together, but individual members are better off by defecting and pursuing their own narrowly defined self-interest

Customs: are generally accepted practices

Epistemic Community: a pool of experts and practitioners in a particular field

General Principles of Law: is something that is recognized in most legal systems

Intergovernmental Organization: is an organization constituted by sovereign states that work together on a particular problem

International Governmental Organizations: is an organization created by three or more states with some form of permanency and that meets regularly

International Law: is a product of diplomacy, treaties, and agreements that seeks to address functional problems and build on established norms that set expectations of conduct in global affairs.

Law of Peace: deals with how states interact with each other, including treaties, diplomacy, state responsibility, international economics, the law of the sea, the environment, and space

Law of War: seeks to regulate the conduct of war, protect categories of people, and prohibit particular weapons deemed inhumane or indiscriminate, such as chemical and biological weapons or landmines

Legal Scholarship: encompasses the written arguments of the most prestigious and respected legal scholars

Odious Debt: is when a country’s government changes and is held responsible for the previous government’s debt which had been used for misdeeds or personal enrichment

Pacta Sunt Servanda: is latin for ‘agreements must be kept’

Supranational Authority: are powers or competencies that are enforced by an institution on states that limits state sovereignty

Treaties: are written conventions between states that establish rules or set limits on behaviour in a particular issue area

References

McBride, James. “How Does the European Union Work?” Council on Foreign Relations. Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed March 22, 2021. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/how-does-european-union-work.

“What We Do.” UN Environment Programme. Accessed March 22, 2021. https://www.unep.org/ozonaction/what-we-do.

Roach, J. Ashley. “Today’s Customary International Law of the Sea.” Ocean Development and International Law 45, no. 3 (2014): 239-59.

Pineschi, Laura., SpringerLink, and Springer, Vendor. General Principles of Law - The Role of the Judiciary. Ius Gentium: Comparative Perspectives on Law and Justice, 46. 2015.

Barnett, Michael, and Martha Finnemore. Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics. Cornell University Press, 2004.

Christodoulidis, Emilios A., Dukes and Goldoni editors. Research Handbook on Critical Legal Theory. Research Handbooks in Legal Theory. 2019.

Supplementary Resources

- Barnett, Michael, and Martha Finnemore. Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics. Cornell University Press, 2004.

- Boas, Gideon. Public International Law: Contemporary Principles and Perspectives. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2012.

- Christodoulidis, Emilios A., Dukes and Goldoni editors. Research Handbook on Critical Legal Theory. Research Handbooks in Legal Theory. 2019.