When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the concept of global civil society

- Explain the concept of an International Non-Governmental Organization

- Explain the concept of transnational social movement

- Describe how global civil society impacts global politics

- Describe how different theories and approaches to global politics make sense of global civil society, INGOs, and transnational social movements

Davies, Thomas. “NGOs and Transnational Non-State Politics.” E-IR, October 2, 2020. https://www.e-ir.info/2020/10/02/ngos-and-transnational-non-state-politics.

Meyer, David and Daisy Reyes. “Social Movements and Contentious Politics” in Handbook of Politics: State and Society in Global Perspective. Ed. Leicht, K and J.C. Jenkins. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 2010.

Kenny, Michael and Randall Germain. “The Idea(l) of Global Civil Society”, in The Idea of Global Civil Society: politics and ethics in a globalizing era. New York, NY: Routledge, 2005.

- Global Civil Society

- Transnational Social Movements

- International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs)

- International Campaign to Ban Landmines

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Greenpeace

- World Social Forum

- National Democratic Institute

- International Republican Institute

- Transparency International

- Amnesty International

Learning Material

In the previous two modules, we introduced and explored the impact of IPE and IGOs on global politics. These modules suggest that global politics has been dominated by MNCs, states and international governmental organizations. To a large extent, this is true. However, this excludes ‘the people’ from our examination of global politics. Yet, there have always been individuals and groups advocating on particular international issues. For example, the ancient Greeks touched on questions of human rights when discussing natural law. As another example and noted in the Just War Theory module, St Augustine discussed the morality of war in the 4th century. However, the roots of contemporary global civil society are found in the 19th century as a multitude of groups began to advocate on issues of war, suffrage, and slavery. In the 20th century, and most notably after world war two, global civil society has grown exponentially in size and diversity. Within the structure of global civil society, the two most important groups are International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs) and transnational social movements. INGOs are more formal groups that undertake programming and/or advocacy on international issues, like global poverty or environmental protection. Transnational social movements are broader phenomena that engage in direct action, often with INGOs’ support, like the women’s rights movement or the environmental movement. In some ways, global civil society represents ‘the people’ in that INGOs and transnational social movements are primarily constituted by individuals who dedicate their time and energy to particular causes. However, as global civil society has received more scrutiny, issues of concern have arisen, largely around representation, accountability, and transparency. However, for those who wish to get involved in global politics, global civil society is perhaps the most effective way to enact agency.

The concept of global civil society is an offshoot of the literature on domestic civil society. In the domestic sphere, civil society is constituted by non-profit groups or organizations that seek to influence government decision-makers in particular areas. For example, in Canada, there is ‘The Council of Canadians’ that seeks to “challenge corporate power and advocate for people, the planet, and our democracy”. The ‘Congress of Aboriginal Peoples’ is another civil society group working in Canada to represent the interests of off-reserve status and non-status Indians, Métis, and Southern Inuit Aboriginal Peoples. Different groups seek to address a wide range of issues, including the environment, corruption, cultural issues, human rights, and workers’ rights. The defining characteristic of civil society groups is that they stand apart from both the state and corporations, as well as those bodies that lobby/advocate on behalf of the government and corporate interests. Global civil society groups operate similarly, but at the international level. They are constituted by citizen groups, social movements, NGOs, and transnational advocacy groups. They engage in “dialogue, debate, confrontation, and negotiation with each other, with governments, international and regional governmental organizations and with multinational corporations”. (Castelos, Montserrat, and Anheier 2001) Some national civil society groups are chapters of global civil society organizations. For example, Transparency International was established in 1993 to advocate, campaign, and research the impact of corruption. There are now 26 national chapters of Transparency International, including one in Canada. Some global civil society groups start as national groups and spread internationally. Greenpeace, for example, began as a Canadian protest against nuclear weapon testing in Amchitka, Alaska in 1971. Greenpeace is now headquartered in Amsterdam, has 26 regional offices, and operates in 55 countries. In its most idealized form, global civil society advocates on behalf of ‘the people’ in global politics, competing with states and multinational corporations. However, as we will subsequently discuss, not all global civil society groups live up to this ideal.

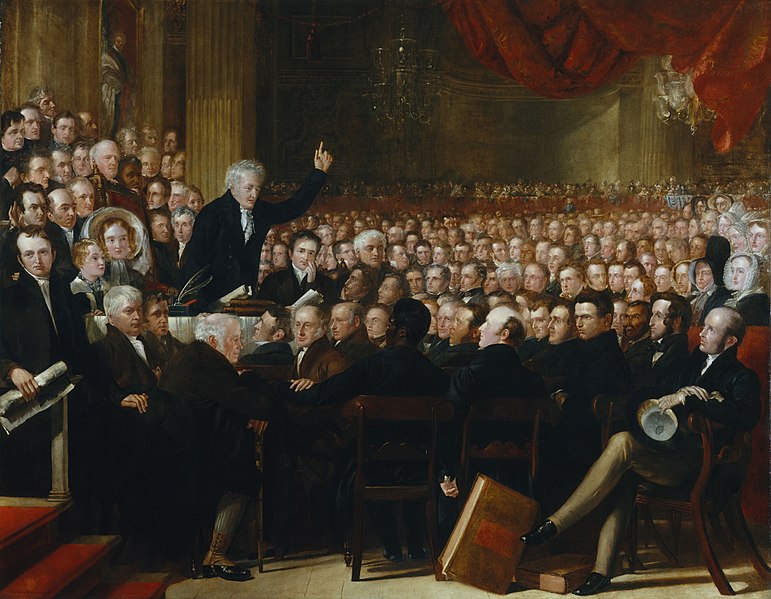

Individuals and groups, separate from official state bodies, advocating on behalf of particular issues is not new. Such advocacy has existed as long as organized politics have existed. However, the contemporary form of global civil society is closely tied to the emergence of citizenship in Europe and the Americas. As subjects became citizens, debates emerged on the rights and obligations associated with citizenship. For example, Alexis de Tocqueville, the 19th-century French philosopher, wrote about the instrumental role that civil society associations played in early American democracy, deeply contributing to the political discourse. Early global civil society movements included efforts for women’s rights, universal suffrage, rights for the poor, labour rights, and anti-war advocacy. One of the earliest and most influential global civil society efforts was the abolitionist movement which sought to ban slavery. The abolitionist movement included slaves and former slaves as well as members of the dominant class in various societies. They were all united by a belief that people could not ethically be treated as objects, as things. The Quakers set up the first British abolitionist organization in 1783. In 1787, Thomas Clarkson and Granville established the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. In 1807 the slave trade was outlawed in Britain, and in 1833 the institution of slavery was abolished, with a few exceptions, in the British Empire. In France, anti-slavery campaigners worked with their British counterparts, briefly abolishing slavery between 1794 and 1802 and finally accomplishing the goal in 1848. In the US, there were abolitionist advocates even from colonial times, for example, the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery. However, it wasn’t until the 1830s that the abolitionist movement became a political force in the US. However, while a growing number of Americans disapproved of slavery, there was no consensus on how to end it, especially given the economic impact of slavery in the American south. In 1864, the US passed the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery. At the international level, the World Anti-Slavery Convention was held in 1840, gathering the various anti-slavery advocacy groups together. The national abolitionist movements and the World Anti-Slavery Convention are examples of early global civil society seeking to challenge and change existing international normative structures.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f9/The_Anti-Slavery_Society_Convention%2C_1840_by_Benjamin_Robert_Haydon.jpg/771px-The_Anti-Slavery_Society_Convention%2C_1840_by_Benjamin_Robert_Haydon.jpg

Global civil society is quite an expansive concept. As suggested above, it encompasses citizen groups, transnational social movements, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), and transnational advocacy groups. However, INGOs are the most prolific and influential part of global civil society. Much like IGOs, the number and type of INGOs have expanded exponentially in the post-war world. According to the Union of International Associations, there were 176 INGOs in 1909, 832 in 1951, and over 60,000 in 2016. INGOs are those organizations that are explicitly global in scope. The most common areas for INGO activities include poverty alleviation, economic development, conflict resolution, human rights, the environment, health care, good governance, and humanitarian assistance. Most broadly, INGOs undertake two types of activity, either exclusively or in tandem. First, INGOs can focus on advocacy. Advocacy seeks to shift policy or behaviour by shaping debates, informing the public, and influencing decision-makers. Research is often an essential part of this process to better inform advocacy. Amnesty International (AI) is an example of an advocacy INGO since it literally advocates on behalf of political prisoners. Second, INGOs can be operational. To be operational means to provide a service or implement a program. Medecins Sans Frontier, or Doctors Without Borders, is an example of an operational INGO. They provide health care in conflict zones, natural disasters, humanitarian crises, and epidemics. Some INGOs are both operational and undertake advocacy work. For example, OXFAM both advocates on issues of poverty/injustice and implements programs to allow people, often women and girls, to escape poverty and gain a voice in their communities. One consideration for all NGOs is funding, an issue we will touch on in the section that critiques INGOs.

The International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) is an interesting case of how INGOs can make a significant difference in global politics, even when facing considerable opposition from some large and influential states. Antipersonnel landmines (APLs) are indiscriminate weapons that injure and kill civilians as well as military personnel. In many cases, civilians are disproportionately affected, especially when people return to their homes post-conflict. It renders large sections of land unusable for agriculture and habitation, creating long-term economic costs. In 1997, before APLs were banned, more than 25,000 people were injured every year. Nearly half of these people were killed, and survivors were often maimed for life, many requiring amputations. By 2013, the number of casualties had been reduced to 3,500. However, numbers have been climbing, largely due to renewed conflicts in previously mined areas and because some non-signatory states are likely still manufacturing APLS, notably India, Myanmar, Pakistan, and South Korea. Even more worrisome, given the 2020 coup and military attacks against ethnic minorities, Myanmar has been actively laying APLs.

The ICBL is an umbrella group representing a range of INGOs advocating for an APLs ban and landmine clearing. In the 1990s, some states were advocating to ban APLs, most notably Sweden. As activism mounted in the 1980s and 90s, there was an effort to review the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW, 1980), an agreement to limit or ban weapons that cause unnecessary suffering to soldiers or civilians. The CCW controls APLs, but only for inter-state conflicts and without monitoring or compliance mechanisms. Efforts to amend the CCW ran into the opposition of countries like India, China, Cuba, and the UNSC P5 states. The UN disarmament process, including amending the CCW, requires consensus. Therefore, significant amendments to the CCW failed. The ICBL took a different approach. They created relationships with civil society groups, like-minded states, and sympathetic IGOs. They created a pincer-like strategy, with like-minded states bringing pressure in IGOs and other state fora, NGOs applying pressure domestically, and INGOs putting pressure on both. Much of the NGO/INGO advocacy was emotional and focused on the immorality of APLs. For example, NGO Mines Action Canada would create piles of empty shoes of landmine victims on the steps of parliament. With the support of the Canadian government, NGOs were allowed into the 1996 CCW review meeting. There were low expectations of the meeting, given the need for consensus in the UN disarmament process. However, the passion of the NGO representatives had created a moral imperative to act. The like-minded states had applied diplomatic pressure to act. And when Canadian Minister for Foreign Affairs Lloyd Axworthy gave the closing remarks, and after consulting with the PMs Office as well as the Secretary-General of the UN, he challenged the 50 governments and the 24 observers present to bring about a comprehensive APL ban by the end of 1997. The result was the 1997 Ottawa Treaty, signed by 122 states and coming into force in 1999. There are now 164 state parties and others, like the US, who agree to abide by the treaty with a few exceptions but have not become a state party. The US, for example, reserves the right to use APLs on the Korean peninsula as they are still technically at war with North Korea.

The ICBL is an instructive and innovative example of how INGOs can make a difference in global politics. The umbrella organization coordinated efforts between NGOs and INGOs, between different countries, and in applying pressure on IGOs. The ICBL combined advocacy with the public, like-minded countries, and IGO officials. Moreover, they maintained attention on the issue and monitor compliance with the Ottawa Treaty. The ICBL received the Noble Peace Prize for their work in 1997.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/International_Campaign_to_Ban_Landmines_Logo.svg/400px-International_Campaign_to_Ban_Landmines_Logo.svg.png

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f2/Friedensnobelpreisverleihung_Internationale_Kampagne_f%C3%BCr_das_Verbot_von_Landminen_1997.JPG/1024px-Friedensnobelpreisverleihung_Internationale_Kampagne_f%C3%BCr_das_Verbot_von_Landminen_1997.JPG

Global civil society, and most notably INGOs, are increasingly active in global politics. People are often motivated to get involved in global civil society action to make a difference. They feel something is wrong or perceive there is an opportunity to change ‘what is’ into ‘what could be’ or ‘what should be’. Most INGOs seek to improve the human condition and must engage with states, IGOs and MNCs to do so. INGOs have to work with states to implement programs within their borders. States are often willing to accept INGO programming because they fill a gap in social welfare provision. This is particularly true in states that had to adhere to the IFIs’ SAPs. IGOs often welcome working with INGOs as this relationship helps IGOs overcome a perceived legitimacy deficit. It is argued that INGOs bring the ‘voice of the people’ into the processes of global politics. INGOs can also provide the labour and expertise to address systemic issues. Think, for example, of humanitarian INGOs, which can quickly mobilize personnel to help in crises. MNCs often work with INGOs to fulfill their commitments to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). CSR responsibilities are increasingly a requirement for MNCs to operate in particular states. It requires MNCs to consider and take responsibility for their operations on local communities, social welfare provision, and environmental impact. INGOs can enhance MNCs’ CSR policies by providing a more positive image as well as resources and know-how.

However, as INGOs have become increasingly visible in global politics, so have the criticism of INGOs, often because of their relationship to states, IGOs, and MNCs. Maintaining these relationships can require INGOs to adapt their policies and programming, which can undermine their legitimacy. More specifically, global civil society, including INGOs, are critiqued for lack of representation, accountability, and transparency. In terms of representation, many have questioned the idea that global civil society represents ‘the voice of the people’. Who are these ‘people’ that global civil society represents? INGOs, in particular, are formal organizations, many with large budgets and often receiving funding from governments and IGOs. They are increasingly led by a small professional class of managers and bureaucrats. They are often based in Western states. Each INGO has its own charter and governance structures. But who chose these INGOs and this cadre of INGO professionals to represent the ‘people’? Most INGOs may believe they are acting in the people’s interests, but many are blinded by their own bias and positionality. Still, others are knowingly acting in their donors’ interests, whether states, IGOs, or MNCs. The issue of representation links to the issue of accountability. To whom are INGOs accountable? There are questions of consultation. Are INGOs working on a particular issue, whether protecting marginalized groups or the environment, accountable to the ‘people’ their programming impacts? More often, INGOs are accountable to their donors, often states, IGOs, and MNCs – the very actors that global civil society is meant to check. Finally, this leads to questions of transparency. Global civil society and INGOs are private actors. Beyond their own charters, there is no obligation to publically reveal donors, decision-making processes, projects, or the efficacy of programming. There is no obligation to reveal the pay for INGO executives. Yet, global civil society actors have an image, albeit somewhat tarnished, for being that ‘voice of the people’ since there are no other current alternatives. For example, Greenpeace is one of the largest and most influential environmental INGOs in the world today. As mentioned earlier, Greenpeace has grown from the house of two Canadian anti-nuclear advocates in 1971 to its current headquarters in Amsterdam, coordinating offices in 26 regional offices operating in 55 countries with annual revenues of around 360 million US$. However, critics argue Greenpeace has no meaningful input from nor accountability to its membership. Instead, a few leaders make the decisions on funding, policy and programming. This raises many questions about who Greenpeace represents and how they do so. However, the takeaway is that the people who support and fund global civil society groups and initiatives should take the time to examine their representation, accountability, and transparency.

At a broader level, global civil society is associated with transnational social movements. Transnational social movements are political formations that seek to affect change, often through direct action such as protests, civil disobedience, and intentional law-breaking. Transnational social movements are much less cohesive than INGOs, often containing a broad range of actors with an equally broad range of tactics and goals. However, they can also be more permanent, facilitating coordination between actors on a particular issue. Historical examples include the abolitionist movement, the suffragette movement, the civil rights movement, and the labour movement. More recent examples include the LGBTQ movement, Occupy Wallstreet, Idle No More, and the World Social Forum. Transnational social are sources of political and social change as well as markers of broad normative shifts. Importantly, they are an opportunity for people to enact agency in both domestic and global politics. Social movements can take a variety of forms, often in response to the context within which they are operating. In more authoritarian states, social movements are more clandestine, whereas, in more democratic states, they are visible and routine. However, the key point is that transnational social movements represent shifting societal mores. They are often akin to the iceberg analogy – what we see is merely the iceberg’s tip above the water. Below the water is a much larger body of discontent that is moving inexorably towards new normative standards. However, it is rare for social movements to achieve their objectives fully. Instead, transnational social movements clash with existing normative standards and most often result in a blend of the two. For example, the women’s rights movement has many victories in terms of removing legal forms of discrimination based on gender, challenging social norms, and sexual reproductive rights. However, women still disproportionately suffer from poverty, lack of health care provision, violence, and employment opportunity.

The World Social Forum (WSF) is an interesting example of a transnational social movement that seeks to challenge global politics at a fundamental level. The most visible part of the WSF is the annual event organized simultaneously with the World Economic Forum held in Davos, Switzerland. The first WSF was held in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 2001, and again in 2002, 2003, 2005, and 2012. In the other years, the WSF was held in a variety of majority world cities with the exception of 2016, which was held in Montreal, and 2008 and 2010, which were decentralized in several different locations. As a movement, the WSF is a vehicle to bring together global civil society groups that oppose neoliberalism, global capitalism, and cultural/economic imperialism and promote alternative political, economic, and social organizations. The WSF brings all these goals together in its motto: “Another World is Possible”. In many ways, the WSF represents the degree of discontent with the current international economic, political, and social orders. In 2002, the second WSF had 12,000 official delegates and over 60,000 attendees. The WSF is a decentralized movement and has suffered from a lack of direction and coordination. This raises questions about whether the WSF will continue. However, what is most noticeable about this debate is not whether the WSF is needed but rather if the WSF needs to be replaced with something more political and more assertive.

When we apply our theories and approaches of global politics to the concept of global civil society, we see a very fractured picture. In many ways, the idea of global civil society distills very different visions of global politics. Realism provides the least room for global civil society in its analysis. As we have repeatedly noted, Realism privileges a world view constituted by states pursuing their national interest in an anarchical system. In this world view, borders are thick, and there is a sharp distinction between the domestic and international realms. Realists largely discount the possibility of global civil society playing a prominent role in global politics since all such actors are geographically located somewhere and therefore beholden to states’ sovereign control. They do recognize the existence of INGOs but believe they are rarely altruistic. Or if they start altruistically, they are quickly co-opted by states and MNCs. Realists argue INGOs work to satisfy the interests of their donors, knowingly or not. The unwitting are useful dupes that are constrained by the need to secure stable funding. Many others are created or exclusively funded by states or MNCs to advance their interests. For example, in 2012, the Egyptian Government cracked down on INGOs supporting pro-democracy movements, including the National Democratic Institute and the International Republican Institute. Both INGOs are almost exclusively funded by the US Government and the two main American political parties. In an interesting twist, the Egyptian Government reversed its decision when the US threatened to revoke its 1.3 billion dollar aid package. These INGOs were important enough to the US Government to apply the threat of economic sanctions and not important enough to the Egyptian Government to pay that price. Save the Children is another example of an INGO acting in the interests of its donors. Save the Children, one of the UK’s largest and oldest charities dropped advocacy campaigns in order to avoid upsetting its sponsors, including energy companies and pharmaceutical companies. For Realists, these are just two examples of INGOs either working directly at the behest of states or being co-opted in order to secure funding.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/e/ee/Save_the_Children_logo_%282016%29.svg/1024px-Save_the_Children_logo_%282016%29.svg.png

Liberals, especially Classical Liberals, see great value in global civil society, INGOs, and social movements. One of the founding principles of Liberalism is that there is a natural harmony of interests between people. We all want to be secure and to prosper. We all want to feel part of the society around us and to participate meaningfully within it. In domestic politics, Liberals fought for the individual’s civil and civic rights against monarchies and dictatorships. In so doing, they enhanced peace and cooperation while mitigating conflict and war. For Liberals, global civil society fulfills this role at least partially. In a world dominated by states and MNCs, global civil society can represent the people’s interests. States may believe conflict and war are in the national interest, but it is unlikely to be the sons and daughters of decision-makers who are killed on the front lines. War may be good for the military-industrial complex but not for the average citizen. The SAPs of the IFIs may be good for the banks and sovereign lenders but not so much for the heavily indebted states in the majority world, nor for their citizens. For Liberals, the more we can amplify the voices of the people, the better we can check the forces that benefit from disorder. Liberals also see value in how global civil society builds networks that transcend borders, facilitate multiple identities, and dilute the artificial distinction between ‘us’ and ‘them’. Transparency International exemplifies this logic. Transparency International works in over 100 countries to expose corruption and promote transparency, accountability, and integrity. For example, they assess to what degree the political process is free of vested interests. They uncover the systems, processes, and actors that facilitate the laundering of dirty money. They research and disseminate their findings on corruption and ways to enhance anti-corruption agencies. And they work on projects that focus on particular areas of concern, for example, land corruption in sub-Saharan Africa or corruption in the resource extraction sector. All of these projects and prescriptions are deeply Liberal in nature. They empower people to make decisions based on fuller information. They seek to expose the corruption that may create tension between people within and between countries. They seek to highlight the natural harmony of interest for all people in good governance and fair electoral processes.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/0/08/Transparency_International_Logo.png

Constructivists are keenly aware of the role that global civil society plays in shaping identities, which influences interests and ultimately practices. Global civil society fosters transnational identities. When people are working on women’s rights, poverty reduction, or environmental protection, they often do so with people far beyond their own borders. Through social interaction, they begin to build shared identities that operate at the global level. INGOs and transnational social movements work to reframe or draw attention to particular issues and apply pressure on decision-makers to behave in particular and sometimes new ways. This process challenges and potentially replaces existing norms in global politics. This is a near literal description of a constructivist argument. Amnesty International is an interesting example from a constructivist perspective. Amnesty International is an INGO that seeks to bring attention to political persecution, the use of torture, the death penalty, and state violence against civilian populations. The Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Amnesty International in 1977. Amnesty International advocacy seeks to challenge norms of state impunity due to sovereignty. It attempts to reframe norms on human rights. It builds a community of human rights campaigners that challenge state violence and privilege. In so doing, Amnesty International has shaped the norms of global politics

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/e/ee/Amnesty_International_logo.svg/1024px-Amnesty_International_logo.svg.png

Critical and Post-structural approaches to global civil society see more nuance in the concept of global civil society, and more specifically, INGOs. They are both highly critical of many INGOs, especially those headquartered in the minority world. These INGOs are often promoting Western ideals of economic development, political institutions, and social organization. For example, the National Democratic Institute and the International Republican Institute are clearly working in the American government’s interest. Even Transparency International is operating in the context of Western values. However, some INGOs, especially grassroots organizations in the majority world, can be a formidable source of resistance to minority world states, IFIs, and MNCs. Critical approaches see great value in such INGOs as they are a means to speak truth to power and achieve their emancipatory goals, whether that be challenging global class structures, promoting women’s rights, or protecting the environment. For Post-Structural approaches, minority world INGOs and global civil society as a whole have played an even more destructive role in global politics. They have been a powerful means to establish and reproduce discourses that privilege global capitalism, the minority world institutions of governance, and the privileged position of minority world states. For example, when the IFIs imposed SAPs in majority world states experiencing economic crises, these states were forced to drastically cut social welfare spending. In response, many ‘white saviour’ INGOs filled the void by providing health care, education, and other social services. However, in so doing, they were creating two problems. First, the need for white saviours reinforced discourses of minority world superiority. It was akin to saying that the majority world could not take care of itself and needed to be saved by the minority world. Second, it created a dependency in the majority world on the minority world that only deepened over time. This reinforced the discourse of minority world superiority. On the flip side, this process of reinforcing the discourse of minority world superiority subjugated discourses that posited imperialism, colonialism, and the global economy’s function as the source of crises in the majority world. Put more bluntly, the volunteers, INGOs, and minority world aid packages that bring food, medicine, and doctors to the majority world cover systems of oppression and coercion that benefit the powerful and rich in the minority world.

https://images.pexels.com/photos/6646864/pexels-photo-6646864.jpeg?auto=compress&cs=tinysrgb&h=750&w=1260

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Amnesty International: is an INGO that seeks to bring attention to political persecution, the use of torture, the death penalty, and state violence against civilian populations

Corporate Social Responsibility: requires MNCs to consider and take responsibility for their operations on local communities, social welfare provision, and environmental impact

Global Civil Society: is constituted by transnational non-profit groups or organizations that seek to influence government decision-makers in particular areas

Greenpeace: is one of the largest and most influential environmental INGOs

International Campaign to Ban Landmines: is an umbrella group representing a range of INGOs advocating for a ban on Anti-Personnel Landmines (APLs) and landmine clearing

International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs): organizations that undertake advocacy and/or operations in global politics, independent from state or MNC control

International Republican Institute: is an INGO that provides training and assistance to political parties abroad and is largely funded by the American government and the Republican Party

National Democratic Institute: is an INGO working to support and strengthen democratic institutions worldwide and is largely funded by the American government and the Democratic Party

Transnational Social Movements: are political formations that seek to affect change, often through direct action such as protests, civil disobedience, and intentional law-breaking

Transparency International: is an INGO that works in over 100 countries to expose corruption and promote transparency, accountability, and integrity

World Social Forum: is a transnational social movement that seeks to challenge global politics at a fundamental level and an annual event that meets simultaneously with the World Economic Forum held in Davos, Switzerland

References

Castelos, Montserrat, and Anheier, Helmut. “Global Civil Society 2001. ”European Journal of International Law 14, no. 5 (2003): 1047-051.

Burton, Orville Vernon. “Debates Over Slavery and Abolition: An Interpretative and Historiographical Essay.” Slavery and Anti-Slavery: A Transnational Archive. Cengage Learning, 2009.

Axworthy, Lloyd. “Canada and Antipersonnel Landmines” in Foreign Policy: Theories, Actors, Cases. Ed. Smith, Hadfield, and Dunne. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Hudson, Kate. “World Social Forum”, The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Mingst, Karen A, Stiles, Kendall W, and Karns, Margaret P. International Organizations: The Politics and Processes of Global Governance. Third ed. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2015.

Quinn, Andrew. “US Embassy Shelters Americans amid Egypt NGO Crackdown.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters, January 30, 2012.

Milmo, Cahal. “The Price of Charity: Save the Children Exposed after Seeking Approval.” The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media, December 10, 2013.

Supplementary Resources

- Givan, Rebecca Kolins, Roberts, Kenneth M., and Soule, Sarah Anne. The Diffusion of Social Movements: Actors, Mechanisms, and Political Effects. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Keane, John. Global Civil Society? Contemporary Political Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Yanacopulos, Helen. NGO Activism, Engagement and Advocacy. Non-governmental Public Action Series. 2015.