- Explain the difference between status quo approaches and outside the box approaches to global politics

- Apply Constructivism to explain how global politics and issues are socially derived

- Explain linkage between particular critical approaches to global politics and their emancipatory prescriptions

- Apply the Post-Structural tools of narrative, deconstruction, and genealogy to global politics

Goldstein, J.S., Pevehouse, J.C., & Whitworth, S., (2008) . “Ch 4 Critical Approaches”, International Relations, 2ndEdition, (pp. 104-128). Toronto: Pearson Education, Inc.

Fierke, K.M., (2010). “Constructivism.” International Relations Theories: Discipline and Diversity, 2nd ed, (pp. 177-194). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ‘A logic of appropriateness’

- ‘A logic of consequences’

- Agency-structure debate

- Constructivism

- Critical approaches

- Deconstruction

- Dependency theory

- Discourse

- Emancipation

- Environmentalism

- Feminism

- Genealogy

- Global capitalism

- Green Theory

- Imperialism

- Import Substitution Theory

- Majority world

- Minority world

- Outside of the box

- Positivist

- Post-Colonial Theory

- Post-positivist

- Poststructuralism

- World Systems Analysis

Learning Material

In module 2, we introduced the status-quo or mainstream approaches to global politics, namely Liberalism and Realism. These two approaches have fundamentally different approaches to understanding and acting upon the world. Liberals see cooperative behaviour as the norm that is facilitated by human beings’ capacity to use rationality and reason to achieve progress to tame the potential for barbarity that we have seen in global politics. Realism, in contrast, argues the world is a much less cooperative place. They claim the potential for conflict is ever-present and that this potential necessitates prudence and security seeking behaviour. They do not argue peace is impossible. Rather they argue peace is only possible if we act on the world as it is, not as we want it to be. Both Liberalism and Realism are fundamentally problem-solving approaches in that they seek to solve issues of conflict and war in the system as it stands. This means Liberalism and Realism take the basic structure of global politics as a given: a world carved into sovereign and self-interested states, operating under the conditions of anarchy. It is this recognition of the system as it stands that differentiates the status quo theories of module 2 from the approaches in module 3. In module 3, we start looking at outside of the box approaches to global politics that question those very things that Liberalism and Realism take for granted. We are going to ask why global politics is constituted in the way that it is. We are going to deconstruct global politics to identify and understand the role that power, interests, and identity have worked to shape it. We are going to question the purposefulness of the system as it stands to reinforce existing privilege and hierarchy. We will start with a bridging theory, Constructivism. Constructivism does not take a position on whether we live in a cooperative or conflictual world. Instead, Constructivism argues we live in a socially constructed world, whose character is dependent on the meaning we generate through interaction, individually and collectively. After Constructivism, we will introduce Critical approaches to global politics. Critical Theories cover a lot of ground, but they tend to focus on two questions.

- One, how did the world/system/process come to take the form and function that it has?

- Two, to whom does the world/system/process serve?

Finally, we will close this module with Poststructuralism. Poststructuralism looks even deeper into the constitution of global politics. It examines the use of language, how that generates meaning, and how that shapes what is taken for granted and believed to be true. Cumulatively, these approaches constitute an approach to global politics that not only thinks outside the box, but the box itself is in question.

Figure 3-2: Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/thinking-outside-the-box-33399/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Clker-Free-Vector-Images.

In the late 1970s, and more forcefully in the 1980s and early 1990s, the dominant approaches of Liberalism and Realism faced new questions by outside the box approaches to understanding global politics. We introduced this tension in module one when discussing the fourth great debate in the field between rationalism and reflectivism. These approaches start by questioning the constitution of global politics. Is it the machinations of self-interested sovereign states pursuing their national interest in an anarchical system that necessitates self-help? That is the generally accepted narrative of Liberalism and Realism. But what is a state? Is the state a natural and given construct? Is it the most extensive form of collective human identity possible? What makes the state sovereign and beyond reproach in terms of its domestic conduct? Who or what determines that someone in Halifax and someone in Victoria are both ‘Canadian’? How can Canada, or any state, be a collective actor? How can the state as a collective actor have a singular national interest? Think about those who constitute the Canadian state. Does a Canadian working in the oil patch have the same interests as a Canadian working in Ontario’s manufacturing sector? What about Indigenous peoples in northern Saskatchewan and a farmer in the south of the province? If these people define their interests differently, how is a singular national interest to be determined? What about the particular and ideological positions that inform state policy? For example, was the Trump Administration working on behalf of American women when it signed the Geneva Consensus Declaration in 2020, joining 10 of the world’s worst offending states regarding women, to limit their reproductive rights?

Figure 3-3: Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo participates in a signing ceremony of the Geneva Consensus Declaration with Health and Human Services Secretary Alex M. Azar II, at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in Washington, D.C., on October 22, 2020. Source: https://www.thenewcivilrightsmovement.com/2020/10/18-months-in-the-making-trump-admin-launches-extremist-manifesto-with-coalition-of-anti-choice-anti-lgbtq-regimes/ Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

These are a lot of questions that cover a wider variety of topics and concerns. However, what all these questions share is a deep suspicion about the taken for granted aspects of global politics found in Liberalism and Realism. They argue that the form and function of global politics is not given – it is a product of particular historical circumstances, representing and reinforcing particular power structures. They argue that it is crucial to question the concepts that constitute the box within which Realism and Liberalism operate – the state, national interest, anarchy, et cetera. Constructivism, for example, starts by questioning the central point of tension between Liberalism and Realism: is the world essentially cooperative or conflictual? Constructivists argue that is the wrong question to ask. Instead, the right question to ask is why global politics is either cooperative or conflictual? A question popularized by Alexander Wendt when he posited ‘Anarchy is what states make of it.’ (1992) For Wendt, the condition of anarchy can be conflictual, or it can be cooperative – it is dependent on the socially derived meaning generated through interaction between states and other actors.

Figure 3-4: Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/social-media-connections-networking-3846597/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of GDJ.

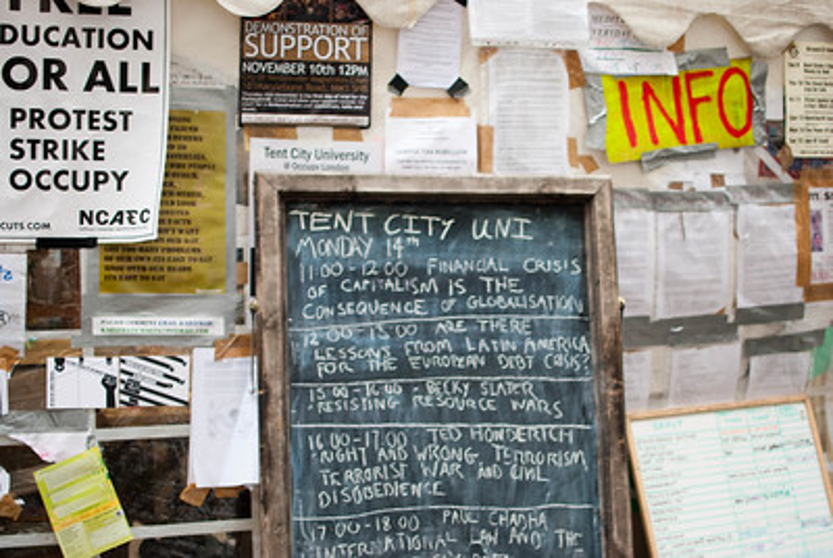

Critical theory takes a more systemic approach in questioning global politics and, more specifically, stands as a critique of status quo theories. Robert Cox sets out the logic here very succinctly when he argues status-quo or problem-solving theories can be very precise in addressing contemporary problems. However, they do not question the system and therefore reinforce the existing institutions and relations of power. Critical Theories, on the other hand, question these institutions and relations of power. By questioning these power dynamics, Critical Theories seek to discern possible futures that are more equitable. There is a wide range of critical theories, some of which have a very long-standing in political philosophy, including Marxism, Feminism, and Environmentalism, to name just a few of the more prominent strands. What unites these disparate approaches to global politics is that they question how the system is constituted, who benefits from the system as it stands, and the role of power in maintaining it.

Figure 3-5: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/aslanmedia_official/6678347253/in/photolist-bb9gYa-UoyrJD-TJQBfd-fNWDsf-pXJk45-2j4R3nK-2hNMgaE-2huqPCd-2iXTpkc-2iRc3iK-2hHbRmL-2iw6Z2Y-2j7vs3w-2hhWrwh-2j7Bx5n-TJyiGQ-5TSMWB-2h1vCzF-6MfnYW-2jdsMHP-2hphbmR-wwS7V-2hjWwdF-Uf3gkk-2j7iWza-2j7CooN-oA3doe-2gcnQ6k-2jqKvSK-2jqqK7t-2j7CYmD-v2Xu5R-uK6akS-2jqAGAk-2j7E72s-2j7D8pY-oiPgyJ-2jcNjf7-2iuSdxi-248UXHj-axMDLB-2hAEMLR-2jammT7-21HusXL-8HgjW8-2hhWo83-2hMXEkC-2icDAVD-3dmd9h-2ipDebd Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Aslan Media.

Post-structuralism, as an approach to global politics, goes even deeper in questioning the contemporary international order. Post-structuralism questions the positivist bias in the mainstream approaches to global politics. A positivist bias in mainstream approaches assumes we can measure, explain, and draw causal conclusions about how and why things happen in global politics. Post-structuralism strongly counters this bias by taking a post-positivist position. A post-positivist approach means that we cannot draw cause-effect relationships because the political world is constituted by human action and human systems/structures. And humans can not be measured like in the study of physics or chemistry. Therefore, post-positivism suggests we cannot explain or predict global politics because we cannot posit causal arguments. As an extension of this argument, post-structuralism argues there is no singular truth to be found. Rather, a full account of global politics requires understanding the contested ‘truths’ at play, and in particular, the power structures that privilege one truth over another. This is accomplished by studying language and discourse as well as deconstructing power relationships. An important implication of a post-structuralist analysis is that it opens the study of global politics to new approaches from different perspectives. For example, the idea of security can be seen through a state-based discourse, a human-based discourse, a geopolitical discourse, a colonial discourse, and economic discourse, et cetera. Each would understand the concept of security differently and, in so doing, understand global politics differently.

Figure 3-6: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/huubzeeman/36732819411/ Permission: CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Huub Zeeman.

Constructivism emerged into the mainstream analysis of global politics in the 1980s, most notably with Alexander Wendt’s publication of “Anarchy Is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics.” (1992) However, Wendt is more responsible for popularizing Constructivism than developing the political philosophy behind it. Wendt drew together the work of symbolic interactionists and social theorists and used simple analogies to make Constructivism more approachable. For example, Wendt asks why policymakers in the United States view the handful of real or potential nuclear weapons in North Korea as more threatening than the five hundred under British control? If the Realists are right, the UK poses a much greater material threat by far than North Korea. However, the Americans, the British, and the North Koreans are acting on an ideational structure versus a material structure. The relationship between North Korea and the US is conflictual, and therefore the North Korean nuclear weapons represent a threat. The relationship between the UK and the US is cooperative, and therefore British nuclear weapons do not represent a threat. Therefore, Constructivists argue it is the socially derived meaning that is most operative, not the simple material reality. In terms of brute material fact, a nuclear weapon under British control is the same as a nuclear weapon under North Korean control. But it is not the brute material fact that makes one weapon more dangerous than another. It is the socially derived meaning attached to them that does so. However, it is useful to go one step further and note that the US and the UK were not always allies. During the American Revolution, the British were the enemy. This suggests that socially derived meaning is not static but rather changes over time and through differing circumstances.

The nuclear weapon analogy is a useful way to highlight the key insights of Constructivism as an approach to global politics. In particular, it suggests three key arguments at work.

First, behaviour is linked to interests and interests are linked to identity. Let us break that down in a bit more detail. Constructivists do not dispute the argument that we act on what we believe to be in our interests. But they argue that our interests are rooted in our socially constructed identities. Identity constructs represent an understanding of who we are, and this is true for both individuals and collective actors like states. Moreover, both individuals and collective actors hold multiple identities. Think of yourself. You are likely a child, sibling, student, and possibly a parent. You might be Canadian, a dual citizen, or maybe a citizen of another country. You might have been born and raised in Saskatoon, or not. You may identify with a particular religion, ethnic group, or even a geographical location like the west, the north, Saskatchewan, or Saskatoon. You may have travelled extensively or never left your hometown. These multiple identities shape your world view. They shape your expectations of yourself and of others. However, note an operative part of that sentence – of yourself and others. It is not simply what I think of myself or what I think of you. Rather, how one understands their identity is shaped through social interaction with others: with friends and enemies, with family and strangers, with those who have authority over us, and with those that we have authority over. Therefore, socially generated meaning happens in that space between actors, where iterated action creates perceptions of each other. If we are friendly and genuine to each other, trust and a relationship is built through iterated or repeated interaction. If we are unfriendly or duplicitous with each other, distrust takes hold, and we may see each other as enemies. This holds true for states as well as individuals – this is essentially Wendt’s argument when he states, ‘Anarchy is what states make of it.’ The US and the UK may have been enemies during the American Revolution, but, over time, their perceptions changed through social interaction, and they have come to see each other as friends and allies. These identities shape our interests. For example, following 9/11, it would have been in the US’s material interest to use its nuclear arsenal against Afghanistan and possibly Iraq or even Iran. No American lives would have been lost, and an enemy would have been defeated. However, such indiscriminate human rights violations would run counter to the American identity of being the defender of democracy and global leader. Instead, the US has embarked on a costly war in the region, both in terms of material resources but also in terms of American lives. Another example would be Germany and Japan’s deep reluctance to build a large standing army despite being advanced and influential states with the wherewithal to do so. The history of Germany and Japan in World War Two has shaped their identities, which in turn has shaped expectations of their behaviour both domestically and internationally.

Figure 3-7: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/prachatai/50472311796/ Permission: CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Prachatai.

Second, social norms are key to a Constructivist approach to global politics. This is directly linked to the point above: actors with firm identity constructs tend to conform to normative expectations. As March and Olsen argue, there are two potential logics that dictate behaviour: ‘a logic of appropriateness’ and ‘a logic of consequences’. (1998) A logic of consequences is closer to a Realist position: that we act on perceived threat or opportunity and that all actors in the same context would act in a similar way, regardless of identity. A logic of appropriateness is a Constructivist position: we act based on identity constructs that contain role expectations generated through social interaction. Again, think of your own life – do you always do what is in your material self-interest (a logic of consequences), or do you act on your role expectations as a friend, a child, or a student (a logic of appropriateness)? Constructivists argue that for most actors, most of the time, the logic of appropriateness is dominant – our behaviour, individually and collectively, tends to conform to expectations we hold of ourselves and others hold of us. Take Canada, for example. For much of the late 20th century, Canada’s foreign policy identity was deeply linked to the idea of being a Middle Power, a ‘good international citizen’, and a supporter of multilateralism. This influenced Canadian foreign policy behaviour. For example, Canada adopted a strong peacekeeping role in the 1960s through to the 1990s largely based on this Middle Power identity. Further, this identity is so entrenched that many Canadians still believe Canada is a strong peacekeeping country, despite drastic reductions to UN missions since the 1990s.

Figure 3-8: Peacekeeping Monument, seen from southeast entrance, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, July 2005. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peacekeeping_monument.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Radagast.

Third, Constructivism combines the first two points to make a contribution to the debate on agency and structure in global politics. The core point of contention in the agency-structure debate is the degree to which actors are able to act independently of social structure. Think back to our discussion of Neo-Realism in module two, where it is argued:

State Behaviour = Non-Differentiated Units + Anarchy + Capabilities

State Behaviour = Non-Differentiated Units + Anarchy+ Capabilities

Therefore: State Behaviour = Capabilities defined in terms of the distribution of resources.

This is a structural approach to global politics with little room for agency. It is a state’s material capabilities that determine the appropriateness of policy decisions. Failure to choose the appropriate policy posed a potentially existential threat – as the Melians found out. However, just to be clear, structural approaches can look to material structures like the Realists, or social structures, like Marxists, who use class to explain political outcomes. (We will look at this briefly in the next section) Liberal approaches to global politics are much more agential. Remember the Liberal mantra that progress is possible through human reason and rationality – through human agency. Constructivism takes a different approach, arguing that structure and agency are mutually constitutive. This means that neither structure nor agency is reducible to each other. Take the example of slavery. A master cannot be a master without a slave, and a slave cannot be a slave without a master. In other words, one does not cause the other, but rather together, they mutually constitute the structure of slavery. This brings us back to the agency-structure debate, where structure is created through agency but once constituted, structure constrains agency. For Constructivists, this mutual constitution of structure and agency allows them to explain continuity and change. Structures resist change as they have inertia. Further, the more a structure is reproduced and reinforced through behaviour, the harder it is to change because such action hardens social norms and expectations of behaviour. Think of a trail horse – the longer it follows a particular path, the harder it is for that horse to deviate from the path, regardless of how hard one pulls on the reins. The path is the structure. However, if one can overcome that inertia and force the horse on to a new path, that is agency. For example, the establishment of the League of Nations created new structures of global politics, with new social norms, based on new expectations of behaviour, rooted in new identities, all of which shaped new interests. An important area of Constructivist research looks into how change and continuity happens. Finnemore and Sikkink make an important contribution here with their work on norm entrepreneurship and norm cascades. (1998)

Figure 3-9: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/scorpiotiger/11808238234/ Permission: CC-BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of C N.

Importance and Impact

Constructivism as an approach to global politics suggests a way forward from the impasse between Liberalism and Realism, and more specifically, whether global politics is essentially cooperative or conflictual. Moreover, it suggests that we operate more on the meaning generated by social reality than a brute material reality. Unpacking this further, Constructivism suggests this social understanding of global politics shapes identities, interests, and behaviour. This behaviour is a form of agency, and when repeated, it establishes social norms. Over time, these social norms can harden into informal and then formal structures. Finally, this mutual constitution of agency and structure lends insight into the possibility of change and continuity in global politics. However, critiques of Constructivism question its ability to be a theory as it is not prescriptive. Rather, they argue Constructivism is more akin to a methodology than a theory – but that is heavily disputed.

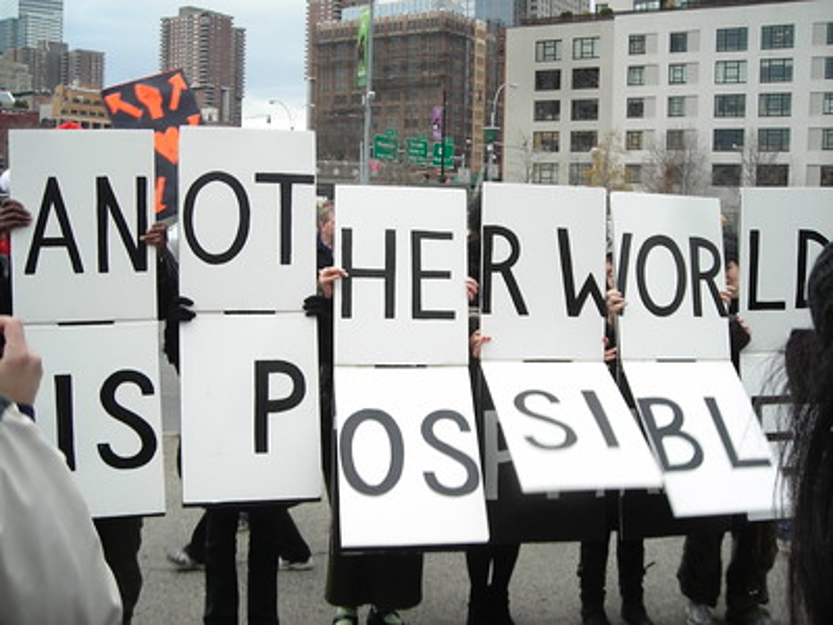

Critical approaches to global politics encompass a wide variety of theories that examine an even wider variety of issues. However, Chris Brown argues two points unite all Critical approaches to global politics. (2019) First, all Critical approaches question the idea that the academic study of global politics is a free-standing discipline that operates on its own logic. Rather, they argue that global politics must be understood as being situated in a broader context of social thought, situated contextually, historically, and within particular power relationships. Second, all Critical approaches seek in some way to rescue the enlightenment project, defined as the ability to overcome superstition, tyranny, and material want through the application of human reason. This may sound familiar as Liberal approaches to global politics also advocated for progress through reason and rationality. However, Critical approaches argue that Liberalism is too mired in status-quo thinking to achieve these emancipatory ideals. This particularly true for Neo-Liberal Institutionalism. This is where these approaches become ‘critical.’ They must challenge the status quo and the power structures that maintain it. They must unpack and explore how the systems of global politics are constituted. And, most importantly, they must seek to discover how ‘another world is possible,’ to borrow a phrase from the World Social Forum. In this section, we will introduce three Critical approaches: Marxism, Feminism, and Environmentalism. That is not to suggest that these three approaches exhaust the breadth of Critical theories because they do not. However, these three approaches provide a broad sample of Critical approaches, each questioning the given aspects of global politics and seeking to provide emancipatory prescriptions.

Figure 3-10: Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/clause-paragraph-book-right-jura-2546124/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

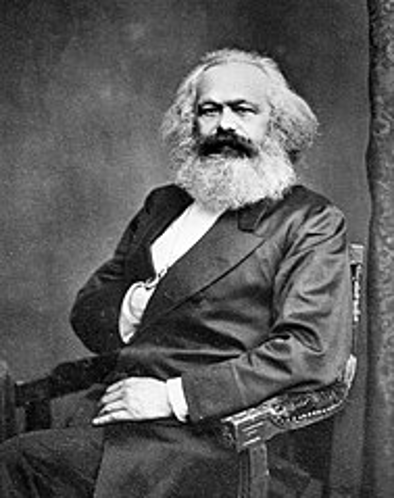

Marxism

The inclusion of Marxism is a bit of a controversial inclusion here as it is not primarily a theory of global politics. Some even question whether it is rightly a theory and suggest it is more a political philosophy that critiques capitalism. And to be fair, we have neither space nor time to explore Marxism’s full extent as a political philosophy. However, in many ways, Marxism is a foundational approach to Critical theories of global politics, especially with its clear focus on emancipation. Moreover, the insights of Marxism have been developed by theorists working specifically on global politics. In broad strokes, Marx focused on capitalism’s form and function and the inherent class conflict in capitalism. He juxtaposed two economic classes that capitalism pit against one another. The first is the bourgeoise constituted by private interests, which both own the means of economic production and control labour/market exchange. The second is the proletariat constituted by labour. Marx posits that the bourgeoisie exploits the proletariat by exacting the surplus-value of their labour and that this exploitation is systematically entrenched in the political and social systems that stem from capitalism. And this is why Marx is important as a Critical approach to global politics – he argues that emancipation is larger than reforming the political system. It is only possible through overcoming economic inequality and the systems that support it.

Figure 3-11: Portrait of Karl Marx. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Karl_Marx_001.jpg#/media/File:Karl_Marx_001.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of John Jabez Edwin Mayal.

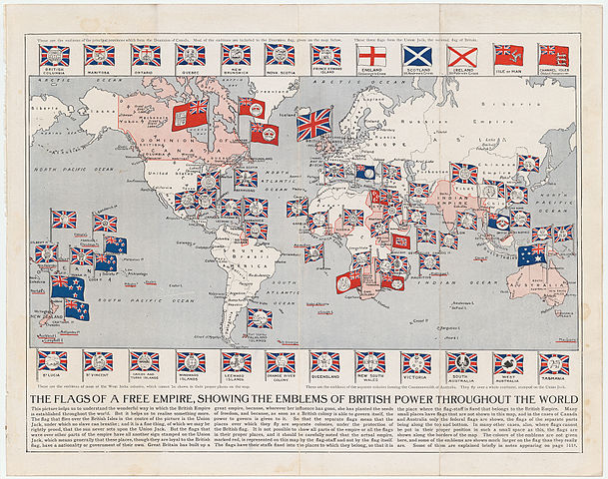

One of the earliest applications of Marxist thought to global politics is a critique of imperialism. One of Marx’s key insights into capitalism is not that it simply extracts surplus value from labour but that it requires continued growth in profit margins. This can be achieved by reducing production costs, raising prices, or developing new markets. Marx hypothesized that when markets are saturated, capitalists will cut costs and that this would lead to lower purchasing power. In order to maintain profits, capitalists will raise prices and therefore exacerbate the tension inherent to capitalism. This leads to a ‘crisis of overproduction’, where more goods are being produced than can possibly be purchased. Marx predicted this would lead to a revolution in the developed capitalist economies. However, later generations of Marxist theorists argue that instead of revolution, capitalist economies turned to imperialism and later neo-imperialism. Imperialism allows developed capitalist economies to exploit less developed states both directly through colonialism or indirectly through economic exploitation. In either case, colonialism and imperialism alleviate the tension within capitalism, at least partially, by providing new sources of cheap labour, cheaper access to natural resources, and new markets to sell their goods back to after extracting the surplus-value. It also puts pressure on labour in the developed economies by using the threat of off-shore production. If domestic labour is too ‘radical’, capitalists will look elsewhere for cheaper and more compliant labour markets. This global nexus of capitalism and imperialism/colonialism has been influential in the field of International Development, specifically in Dependency Theory and World Systems Analysis.

Figure 3-12: The Flags of a Free Empire, Showing the Emblems of British Empire Throughout the World. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arthur_Mees_Flags_of_A_Free_Empire_1910_Cornell_CUL_PJM_1167_01.jpg#/media/File:Arthur_Mees_Flags_of_A_Free_Empire_1910_Cornell_CUL_PJM_1167_01.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Arthur Mees.

Dependency theory extend Marxist thought to the global system, most specifically the international economic and political orders. They argue that global capitalism has created an asymmetric international order that fosters a structural dependency of economically developing states on economically advanced states. Moreover, institutions of international economic and political governance reinforce this dependence. Such institutions include the UN, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, and less formal institutions such as the Basel Group, stock markets, and trade blocks. This is a clear global analogy to the exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie in the domestic context, which is supported by the state’s political and social institutions. As a means of emancipation, Dependency theorists argue that economically less developed states use political instruments to insulate their markets from the global market and allow domestic firms to build capacity and resiliency. For example, Import Substitution Theory argues that the state should select and defend key ‘infant’ industries with tariffs and other non-tariff barriers to trade. The goal is to foster these industries, allowing them to mature and become competitive globally. This runs counter to dominant narratives of international trade that focus on free trade, comparative advantage, and most especially Neo-Liberalism. Neo-Liberalism forcefully argues for privatization, deregulation, globalization, and opening the markets of developing economies to unfettered foreign direct investment. Critiques of Dependency theory argue that while the logic of policies of import substitution may sound good, it is difficult to apply in practice. This is because state involvement in the economy privileges political decision making and is therefore prone to self-interested calculations at best and corruption at worst. For example, country X supports industry Y in order to facilitate its global competitiveness. However, when country X tries to withdraw that protection, those with an interest in industry Y will feel threatened. They then might push back against the party in power and threaten them politically, especially at election time. This creates a political disincentive to withdraw protection, and yet a failure to withdraw protection can lead to inefficiency and a lack of global competitiveness. Examples of Dependency theory prescriptions are often found in the history of development in Latin America, including both successful cases and the many debt crises.

Figure 3-13: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/verbingthenoun/6350209361/ Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Alexa S.

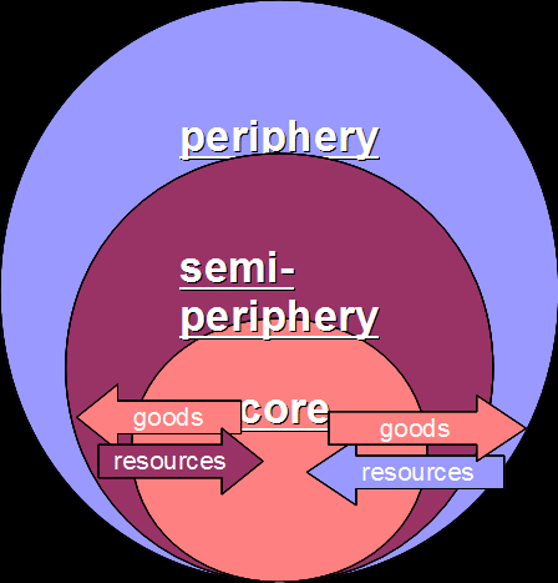

World Systems Analysis also argues that there is an intimate relationship between politics, both domestic and international, and global capitalism. Moreover, they both agree that class is an important analytical lens with which to understand inequality in the international order. World System Analysis differs from Dependency theory in that latter takes a bottom-up approach while World Systems Analysis takes a top-down approach. Dependency theory looks at how the state in the developing world can seek to overcome structural inequality. On the other hand, World System Analysis takes global capitalism as the main unit of analysis and looks at the world capitalist system’s historical development. In this approach, all states are constituted by an inner core of capitalists and political elites and a periphery of labour – much like Marx described. However, at the global level, these states fall into one of three categories: core states, semi-periphery states, and periphery states. This hierarchy of states constitutes global capitalism, with labour and resources flowing towards the core and goods with surplus-value flowing towards the periphery. A key insight of World Systems Analysis is that the states in the core, semi-periphery, and periphery are not a given. Rather it is argued that the hierarchy of states is a function of history and the context of economic/political practices. As a means of emancipation, World Systems Analysis seeks to provide an alternative narrative of international development from the dominant narrative of modernization theory. Modernization theory suggests that less economically developed states should follow the path set by the more economically developed western and European states. But such a suggestion ignores the historical and contextual nature of global capitalism. It ignores the privilege of the dominant states, which have an interest in keeping poorer states underdeveloped. World Systems Analysis suggests overcoming these systemic obstacles to development by understanding the system’s historical nature and the power structures that support it. As an example of World System Analysis, theorists often look to the semi-periphery states that have managed to overcome development hurdles, like the Asian Tigers – South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong. These states have transitioned from periphery states to semi-periphery, if not core states, often discounting dominant development narratives.

Figure 3-14: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_system_sphere.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Piotrus.

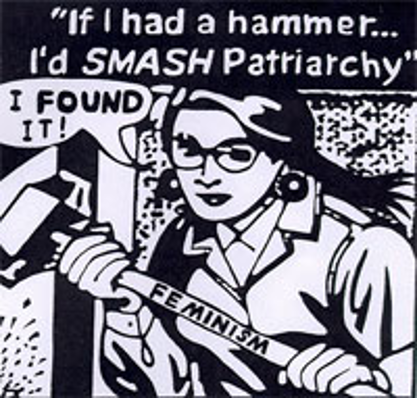

Feminism

Feminist approaches to global politics are firmly rooted in the critical tradition, as described above. First, Feminist approaches are deeply skeptical of the claim that global politics is a free-standing discipline. Rather, they see the privileging of patriarchy and masculinity in the theorization and practice of global politics as another example of women’s systemic subordination and coercion. Patriarchy defines systems where men hold positions of power and decision making, which tend to privilege male interests and concerns. Second, Feminist approaches to global politics seek to emancipate women from systemic inequality, injustice, and exploitation. Feminist approaches try to accomplish this by identifying and explicitly recognizing women’s lived experiences, their contributions to society, and rewriting history to give substance to these findings. In essence, Feminist approaches to global politics start from asking these questions: where are the women in political, economic, and social leadership positions? Where are the women in the history books? Where are women’s interests and concerns? More recently, these questions have evolved to ask not only ‘where are the women?’ but, more specifically, which women and where? This iteration of the question recognizes intersectionality. Intersectionality posits overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination and/or disadvantage. Women are not a monolithic category but rather one characteristic of many, including race, ethnicity, class, and sexual orientation, for example. In the end, most feminist approaches seek to create space for women’s authentic voices in global politics. However, beyond these unifying elements, Feminist approaches to global politics vary quite significantly.

Figure 3-15: Sarah Brown leads the Women for Women International ‘Join Me On the Bridge’ campaign march to the Millennium Bridge. With her are Cherie Lunghie and Annie Lennox, 8 March 2010. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/downingstreet/4417088070 Permission: CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Downing Street.

Critical Feminist approaches to global politics emerged out of Liberal roots. Liberal Feminist approaches to global politics are an extension out of the domestic fight for equal political and civil rights. The focus is on changing institutions’ formal rules, for example, voting rights, and increasing representation of women in these institutions. These feminist movements are well known in domestic politics – think of Emmeline Pankhurst in the UK, Susan B. Anthony in the US, or The Famous Five in Canada. If you are unfamiliar with The Famous Five, they fought for women’s legal recognition as ‘persons’ under the British North America Act of 1867. In 1928, the Supreme Court ruled women were not ‘persons’ and therefore could not be appointed to the Senate. The Famous Five pursued the case to the Judicial Committee of the British Privy Council, the highest court of appeal for the British Empire, and in 1929 it was decided that the women were, in fact, ‘persons’ according to the BNA. This Liberal Feminist approach is still quite active in global politics, as NGOs support women’s political and civil rights in many economically developing and decolonized states. There are also significant efforts to achieve institutional equality in international courts, tribunals, and UN bodies. As Kinsella notes, many working in the Liberal tradition draw a connection between gender inequality and economic underdevelopment, corruption, and war. (2020) The WomanStats Project at Brigham University supports this claim by drawing correlations between gender inequality, measured by social, political, and economic indicators, and the propensity to use coercion and violence to pursue state interests. This includes the use of force domestically and internationally.

Critical Feminist approaches to global politics challenge the Liberal ‘just add women’ prescription to pursuing women’s rights. Instead, critical Feminist approaches argue that more fundamental change is required at the political, economic, and, most notably, the social level. They argue that simply changing the rules or seeking greater representation of women are token changes – they do not touch the underlying norms, institutions, and structures that built and maintain patriarchy’s dominance. They argue that patriarchy starts with gendered expectations in society. For example, who does what kind of work? Who is expected to work inside the home vs outside the home? Who deserves to get paid for their labour? Who deserves an education? Who is allowed to control family assets? For critical Feminist approaches, these answers almost always privilege males over females due to the prevalence and force of patriarchy. These dominant gendered expectations shape national and international structures despite nominative increases in women’s representation. Therefore even when women achieve the highest positions in global politics, whether that be the head of state or in international bodies, they are constrained by a culture that privileges patriarchy. Moreover, when ‘women’ are front and center in global politics, it is most often in the role of a victim needing to be saved by developed states – in other words, white men coming to the rescue of generic women threatened by local despots and terrorists. In reality, such rhetoric facilitates and legitimates the use of violence that often leaves real women in a more precarious position than before the arrival of the white saviour. For example, US military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan often use women to legitimate their actions. For critical Feminist approaches to global politics, emancipation is only possible through substantive and transformative change. It is only possible by recognizing the corrosive history of patriarchy. It is only possible by recognizing women’s contributions to the political, economic, and social orders. It is only possible by creating space for authentic women’s voices. Women have much to contribute but need to make the case personally and not through males speaking on their behalf. For the most radical Feminist critique of global politics, the goal goes beyond creating authentic space to create change. It requires recognizing the patriarchal basis of global politics as the perpetuation of structural violence against women. Emancipation, therefore, requires a fundamental transformation of the global political, economic, and social order.

Figure 3-16: Source https://www.flickr.com/photos/thefuturistics/3474392802/ Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of thefuturistics.

Environmentalism

As an approach to global politics, Environmentalism is arguably the most critical of the system as currently constituted and most demanding in terms of emancipation or change. Environmental movements entered into the mainstream discourse in the 1960s, as activists began to highlight the increasingly detrimental impact of our industrial societies on the natural world and, by extension, human health. Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring in 1970, which traced the impact of mass pesticide use on the environment, the food chain, and our well-being. The Cuyahoga River fire in 1969 literally lit a river on fire due to industrial pollution. There are just examples that galvanized domestic and international actors to respond by creating NGOs, establishing environmental protection agencies, constructing global bodies for environmental research, and signing both bilateral and multilateral agreements on environmental protection. Environmental approaches to global politics are currently deeply concerned over the world’s carrying capacity – the maximum population size the planet can sustain in terms of food, habitat, and the necessary resources of life. With over seven billion people on the planet living an increasingly industrial, urban, and mass consumer lifestyle, many argue we have surpassed, or will soon surpass, the planet’s carrying capacity. Environmentalists support their argument with evidence of climate change and increasingly frequent and more adverse climate events. They point to the deep impact of human activity on the land, the sky, and the oceans. They paint an apocryphal picture of existential crisis where the question is not if we can change how we organize politically, economically, and socially but rather the consequences of not doing so. In the end, Environmentalism forcefully argues that we must contest the current form and function of global politics in order to emancipate the world from destructive practices and, in so doing, emancipate us all from an existential threat.

There are many Environmental approaches rooted in a status quo mentality. These approaches look for technological solutions to save us from ecological disaster. Or they look to capitalism and private ownership to price negative environmental externalities and responsibly cultivate natural resources. These status quo Environmental approaches are trying to solve problems within the constraints of the system as constituted. However, critical Environmental approaches use ecological impact as a means to assess what must be done regardless of the current political, economic, and social order. One of the most robust critical Environmental approaches is Green Theory. Green Theory starts with a critique of global politics itself. Status quo theories of global politics privilege the sovereign state and capitalism, which, in turn, stress economic competition and disincentives to political cooperation on environmental issues. Therefore, from a Green Theory perspective, status quo theories cannot solve our global ecological dilemma – they have neither a vocabulary nor a will to do so. Green Theory starts with two suppositions. First, collective human action is driving climate change. In other words, climate change is anthropogenic. Second, climate change poses an existential threat that not only suggests a need but rather a demand for radical change to avoid the next extinction-level event. In other words, we should not be protecting state sovereignty, but we should be protecting the earth for current and future inhabitants. This suggests a need for an ecocentric approach to global order instead of an anthropogenic approach that prioritizes short-term political interest. Green Theory does not allow for compromise nor trade-offs: not for international development, not for maintaining western lifestyles, and not for corporate profit. Instead, Green Theory argues we need to work with cities, regions, civil society groups, and individuals who are committed to an ecological approach out of necessity. (Goodin, 1992)

Figure 3-17: Global Warming (Effetto Serra) Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/rizzato/2671575856/ Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Roberto Rizzato.

Importance and Impact

While there is a significant variety in Critical approaches to global politics, they all share two keen insights. First, critical approaches break out of the box constituted by status quo approaches to global politics, which take for granted the sovereign state, global capitalism, and mainstream norms of ‘how things work’. Instead, they argue that we need to understand the global political, economic, and social order as historically contingent and embedded in particular power structures. Second, all critical approaches are rooted in the enlightenment ideal of emancipation, which seeks to better the human condition by speaking truth to power. If we understand how existing structures privilege some at the expense of others, it possible to build more equitable and just systems. In other words, Critical approaches seek progress and greater equity in global politics and do not take anything as given in that pursuit.

Post-structural Approaches are even more deeply ambivalent to established narratives of global politics than critical theories. Post-Structuralism is deeply skeptical of the possibility of grand unifying theories (GUT) or the possibility of a singular truth. GUTs and singular truth are entrenched in a positivist world view. Positivists argue that the social world can be studied in the same way that we study the natural world – we can explain what happened through causal laws/generalizations that are derived from observation and measurement. We can then explain what happened to predict what will happen based on these discovered casual laws/generalizations. For example, the Realist argument that power determines actions. Post-positivists contest this argument. They argue the social world cannot be studied in the same way as the social world because people are not chemical reactions. Rather, post-positivists argue the world is constituted by ideational structures that can only be understood through interpretation – we can only understand social phenomena by diving deep into the historical and contextual construction of what is, and this does not allow predicting what will be. A simple way to juxtapose these two positions is to think of the idea of observation. Positivists argue we can be akin to the scientists in the lab coat, observing global politics from the outside. We are not part of the experiment, rather we stand apart. Post-positivists argue it is impossible to be a neutral observer on the outside of a social phenomenon. This is because the observer is a product of their own worldview, bringing their own understanding of that which they are studying. The ‘observer’ is part of the experiment, not external to it. This is the tension between explaining and understanding global politics that is an intimate part of the fourth debate discussed in module one.

Figure 3-18: Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/Ctaj_HCqW84 Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Susan Yin on Unsplash

As an approach to global politics, Post-Structuralism denaturalizes important concepts like the state, sovereignty, democracy, or global capitalism. In so doing, space is created for other global approaches to politics that give voice to the marginalized or those who do not benefit from the existing system. Post-Structuralism asks us to think about how global politics has been purposefully constructed for the benefit of some and to the detriment of others. It uses three key concepts to do so: discourse, deconstruction, and genealogy. Discourse is a linguistic system that provides meaning and structure to our social world. Importantly, this meaning is not value-neutral but instead works to support systems of privilege and power. For example, the discourse of ‘democracy’ privileges western norms of competitive party politics. Any other form of electoral system is deemed ‘undemocratic’, and therefore less legitimate. In Canada or other western states, this discourse of democracy gives legitimacy and confers great power to the existing political parties and the people and groups that back them. It also privileges western democratic states over those with other electoral systems, even if such systems have a history and function better suited to their polity. The narrative of democracy has been so internalized, so reified that it is almost unquestioned. Post-Structuralists call discourses that have become ‘truth’ dominant narratives. However, think of the US or Canada. They are both ‘democratic states’, but their electoral systems are very different and support undemocratic practices in many ways. Yet, changes to the electoral system or the assessment of other electoral systems are quickly delegitimized as less democratic or undemocratic. Alternatives to the dominant narrative are called subjugated discourses – and that term, ‘subjugated’ speaks to the coercion involved in privileging one set of ideas over another through this linguistic system. And all of this supports the privilege and power of elites that constitute the system.

In order to make sense of narratives and the tension between dominant and subjugated discourses, we need to look at deconstruction. If discourse is a linguistic system, then the language that constitutes it needs to be understood in relation to other concepts, often opposites. We know what democracy means by juxtaposing it with its opposites, undemocratic, authoritarian, and autocratic, for example. If language is unpacked or deconstructed, we find a hierarchy between good, right, and true versus bad, wrong, or false.

Think of the term developed versus developing states in the field of international development. Developed means successful, wealthy, established, and resilient. In other words, it conveys a meaning of good, right, and true. By implication, developing means less than, incomplete, weak, and vulnerable. In other words, it conveys a sense of bad, wrong, and false. This hierarchy is not natural but purposefully created through discourse to privilege elite interests. Post-Structuralists deconstruct narratives to understand how they have come to be reified or treated as a singular truth. They ask who benefits from this process and who is harmed. These dominant narratives define what Foucault called genealogy or the ‘history of the present’. (Koopman, 2013) Post-Structuralists use genealogy to unpack ‘history’ to reveal what discourses were privileged and which were suppressed. This process of contestation is highly political, privileging power. Think of the adage, ‘the winner writes history’. The process of genealogy takes an operative concept, like democracy, and asks two questions. First, what political practices have attached particular meaning to the contemporary discourse of democracy? Second, what alternative discourses have been marginalized and subjugated? Besides identifying the purposeful privileging of one discourse by and for the elites, genealogy identifies alternative narratives, making space for alternative theories and practices.

Figure 3-19: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/patrick_colgan/270725189/ Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Patrick Colgan.

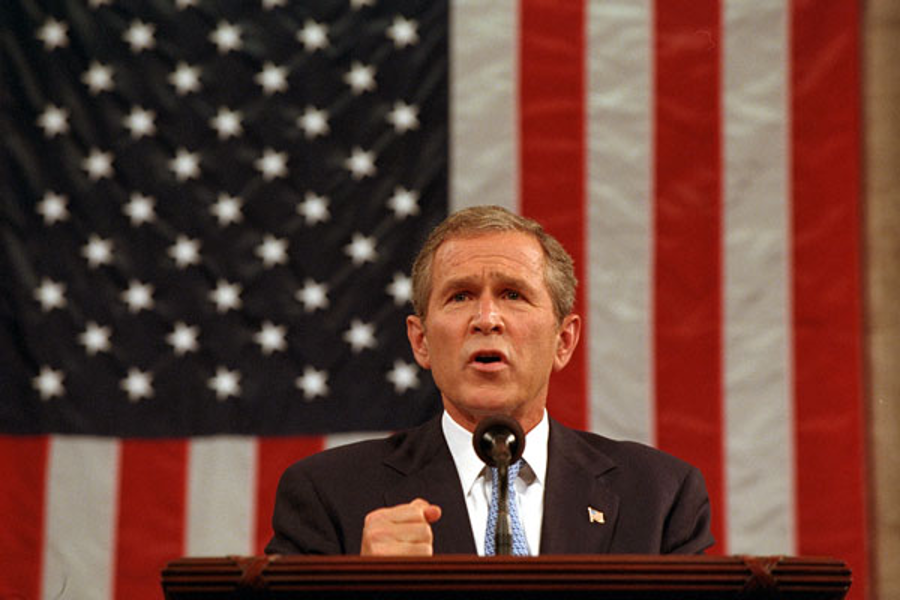

For an example of how this works, think of elites’ role in framing the concept of terrorism and terrorists following the events of 9/11, 2001. In his State of the Union address following 9/11, President G.W. Bush labelled states perceived to be supporting terrorism, or at least anti-American sentiment, as the ‘axis of evil’. Al Qaeda was described as an extremist organization that launched an unprovoked attack against an unprepared and guiltless America. The goal of Al Qaeda was evil and senseless destruction. They attacked the US because they hated America’s freedom. The argument was made that the attacks of 9/11 were quantitively different from what has come before – it was transnational terrorism perpetuated by extremist Islam against the west. This justified a Global War on Terror. He concluded with the argument that you are either with us or you are with the terrorists. A Post-Structuralist analysis would identify the dominant and subjugated discourses at play. It would look to the meanings being applied to concepts, especially through opposite dyads. For example, the enemy is the axis of evil, and that implies we are the alliance of good. They are extremists, filled with hate, envy, and irrational violence. We are good and peaceful, living in a land of freedom. They pose a global existential threat, and we will stand up to do what is right and fight this global war. This juxtaposition privileges a narrative of American virtue, freedom, power, and hegemony while denigrating any alternative discourse on American foreign policy in the Gulf. These alternative discourses might highlight support for dictatorial regimes like Saudi Arabia or putting American interests in oil over human security concerns. These other explanations of 9/11 are subjugated discourses that seek to challenge the dominant discourse above, a dominant discourse that, according to a Brown University report, has legitimated over 20 years of war and has cost an estimated 6.4 Trillion dollars and nearly 800,000 lives. (2019) Understanding these competing discourses requires deconstructing the power relationships that constitute them. It requires exploring its genealogy and recognizing the political practices that form accepted history and subjugate alternative understandings.

Figure 3-20: During a speech to a joint session of Congress, President George W. Bush pledges “to defend freedom against terrorism”, September 20, 2001. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/September_11_attacks#/media/File:President_George_W._Bush_address_to_the_nation_and_joint_session_of_Congress_Sept._20.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Eric Draper.

Post-Colonial Theory

Post-Colonialism and Post-Structuralism are not co-terminus. But Post-Colonial theory is deeply influenced by the intent and tools of Post-Structuralism. Post-Colonial approaches to global politics start from a simple observation. A very small minority of the world’s population dominates the theory and practice of global politics, while the lived reality of the vast majority of the world’s population is absent. An interesting way to conceptualize this relationship is to use the terms minority world vs majority world. These terms replace other dyads like Global North/Global South or developed economies/developing economies. The minority world is constituted by economically advanced economies. These states, and their interests, are well represented in the global economic, political, and social orders. Citizens of these states hold key positions in international institutions, academia, and NGOs. Many of these states have a history of colonialism and imperialism, through which they have exported their economic, political, legal, and social structures. The minority world includes European powers like France, the UK, Germany, and former European colonies like the US, Canada, and Australia. While only representing a fraction of the world population and world geography, they dominate global politics. The majority world is where most people in the world reside in conditions that are far from the ideals of the minority world. The vast majority of these states were either created by the colonial/imperial policies of the minority world or were subjugated by them. The conceptual utility of the minority world/majority dyad is that it is more accurate than other descriptors, and it resonates with the idea of legitimate representation. If the global institutions are not representative of the majority world and yet are acting on majority world issues, how legitimate can they be? For example, two of the most important institutions for international development, and therefore the majority world, are the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. The World Bank and the IMF, by a gentlemen’s agreement, are always headed by an American and a European. The distribution of voting quotas ensures that the US and European states can maintain this agreement.

Figure 3-21: IMF World Bank 2010 _ 01. Source: https://flic.kr/p/8Hah3Y Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of International Monetary Fund.

In other words, Post-Colonial theory deconstructs how global politics privileges the minority world through dominant discourses of development, democracy, and a patriarchal sense of good governance. It is supported by a genealogy that privileges colonial and imperial powers while simultaneously erasing the impact of colonialism and imperialism on the majority world. By deconstructing the dominant narratives that explain why the minority world believes it has the right to dominate the theory and practice of global politics, the coercive role of instrumental power and structural violence is recognized. This recognition opens a space for alternative theories that legitimate the plurality of voices in the majority world. It legitimates alternative language like majority world and minority world. It legitimates a criticism of minority world privilege as well as a history and the contemporary practice of minority world coercion. It empowers the plurality in the majority world to define for themselves what constitutes equitable and just political, economic, and social systems.

Importance and Impact

Post-structural approaches to global politics focus on how power is used to privilege particular narratives that stake truth claims. They note how some dominant narratives become so accepted, so internalized, they become unquestionable. Post-Structural approaches use discourse, deconstruction, and genealogy to unpack these dominant narratives to see what voices have been privileged, what voices have been silenced, and to what effect. This approach’s advantage is the ability to open space for new voices and new theories, often from the majority world, to understand global politics differently.

Over the duration of this course there are questions to consider about the topics we engage with. Copy the following questions into a journal you are keeping, such as a Word Document, and respond to the questions. Over the term you will be asked to submit portions of this journal as part of the evaluation framework. Summary In module three, we have questioned the narrative laid out in module two, most specifically the problem solving approaches of Liberalism and Realism. Problem solving approaches take for granted the structure of global politics: a world carved into sovereign and self-interested states, operating under the conditions of anarchy. These approaches ask questions of how to solve problems within systemic constraints. Outside the box approaches to global politics are deeply sceptical of this position. They ask different questions. They ask why the system is constituted in the way it is. They interrogate the purposefulness of the system and the history of its construction. The ask questions of power and privilege as well as coercion and structural violence. With that being said, the approaches here do differ significantly. Constructivism is the most ambivalent inclusion here. It does seek to understand how the structures of global politics are socially derived, but it does not offer prescriptions like the other approaches. However, it does open the door to other possibilities for global politics by highlighting the role that ideas and social interaction plays in defining identities, interests, behaviour, and ultimately the character of global politics. Critical approaches go further. They argue global politics is not an isolated discipline but is instead a part of a larger picture of social processes. They argue that by understanding this allows a rescue of the enlightenment project, where we can emancipate ourselves through reason. But their emancipatory prescriptions go beyond those of Liberalism by seeking to confront structures of power. Finally, we closed with Post-Structuralism, which uses narrative, deconstruction, and genealogy to understand how global politics is represents historical processes that privilege dominant narratives that reflect elite interests. By understanding global politics as a historical process, we can find the narratives that were subjugated, the voices that were silences, and open space for new possibilities. Figure 3-22: box 3 another world is possible. Source: https://flic.kr/p/aWVbbi Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Pamela Drew.

Review Questions and Answers

Marxism is a foundational approach to Critical theories of global politics, especially with its clear focus on emancipation. Marx focused on capitalism’s form and function and the inherent class conflict in capitalism. He juxtaposed two economic classes that capitalism pit against one another. The first is the bourgeoise constituted by private interests, which both own the means of economic production and control labour/market exchange. The second is the proletariat constituted by labour. Marx posits that the bourgeoisie exploits the proletariat by exacting the surplus-value of their labour and that this exploitation is systematically entrenched in the political and social systems that stem from capitalism. Dependency theorists extend Marxist thought to the global system, most specifically the international economic and political orders. They argue that global capitalism has created an asymmetric international order that fosters a structural dependency of economically developing states on economically advanced states. Moreover, institutions of international economic and political governance reinforce this dependence. Such institutions include the UN, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, and less formal institutions such as the Basel Group, stock markets, and trade blocks. This is a clear global analogy to the exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie in the domestic context, which is supported by the state’s political and social institutions. As a means of emancipation, Dependency theorists argue that economically less developed states use political instruments to insulate their markets from the global market and allow domestic firms to build capacity and resiliency. World Systems Analysis also argues that there is an intimate relationship between politics, both domestic and international, and global capitalism. World System Analysis takes global capitalism as the main unit of analysis and looks at the world capitalist system’s historical development. In this approach, all states are constituted by an inner core of capitalists and political elites and a periphery of labour – much like Marx described. However, at the global level, these states fall into one of three categories: core states, semi-periphery states, and periphery states. This hierarchy of states constitutes global capitalism, with labour and resources flowing towards the core and goods with surplus-value flowing towards the periphery. A key insight of World Systems Analysis is that the states in the core, semi-periphery, and periphery are not a given. Rather it is argued that the hierarchy of states is a function of history and the context of economic/political practices. As a means of emancipation, World Systems Analysis seeks to provide an alternative narrative of international development from the dominant narrative of modernization theory.

Both Feminism and Environmentalism adopt the critical positions that global politics cannot be understood as a free-standing discipline and that emancipation from superstition, tyranny, and material want is possible through the application of human reason. Further, they both provide prescriptions to achieve such emancipation.

Feminist approaches are deeply skeptical of the claim that global politics is a free-standing discipline. Rather, they see the privileging of patriarchy and masculinity in the theorization and practice of global politics as another example of women’s systemic subordination and coercion. Feminist approaches to global politics, therefore, seek to emancipate women from systemic inequality, injustice, and exploitation. They seek to accomplish this by identifying and explicitly recognizing women’s lived experiences, contributions to society, and rewriting history to contribute to these findings. They go beyond Liberal Feminist prescriptions of simply changing the rules or seeking greater representation of women because these are token changes – they do not touch the underlying norms, institutions, and structures that built and maintain patriarchy’s dominance. They argue that patriarchy starts with gendered expectations in society. These dominant gendered expectations shape national and international structures despite nominative increases in women’s representation. For Feminist approaches to global politics, emancipation requires, at a minimum, recognizing women’s role in society and giving space for authentic women’s voices. For some, emancipation demands more, up to and including a fundamental transformation of the global political, economic, and social order. Environmentalism is arguably the most critical of the system as currently constituted and most demanding in terms of emancipation or change. For example, Green Theory starts with two suppositions. First, climate change is anthropogenic. Second, climate change poses an existential threat. This suggests a need for an ecocentric approach to global politics instead of an anthropogenic approach that prioritizes short-term political interest. Green Theory argues we need to work with cities, regions, civil society groups, and individuals who are committed to an ecological approach out of necessity.

Glossary

'A logic of appropriateness': is situational decision making based on normative expectations of social norms

'A logic of consequences': is narrowly defined self-interested decision making based on calculated cost-benefit analysis

Agency-structure debate: describes the tension between independent action and social or other material limits to independent action.

Constructivism: is an approach that argues social facts and the social construction of meaning explain the form and function of global politics

Critical approaches: all argue that global politics must be seen as situated in a broader context of social thought and that through human reason we are able to emancipate those who are marginalized in global politics

Deconstruction: is an approach to understanding the internal structure of narrative and the power relationships within them

Dependency theory: argues that global capitalism has created an asymmetric international order that fosters a structural dependency of economically developing states on economically advanced states

Discourse: a linguistic system that provides meaning and structure to our social world

Emancipation: is the process of alleviating marginalized people from superstition, tyranny, and material want through the application of human reason

Environmentalism: uses ecological impact as a focus of studying processes, structures, or outcomes

Feminism: assesses and looks to further the equality of women

Genealogy: defines the history of the present and is used to unpack the tension between dominant and subjugated discourses

Global capitalism: an asymmetric international order that fosters a structural dependency of economically developing states on economically advanced states

Green Theory: an ecological lens by which to understand and prescribe policies in global politics

Imperialism: is the coercive imposition of one country over another often through the use of military force and often for economic benefit.

Import Substitution Theory: is a policy to protect infant industries in economically developing states until they mature and become global competitive through tariffs and non-tariff barriers

Majority world: is where most people in the world reside in conditions that are far from the ideals of the minority world. The vast majority of these states were either created by the colonial/imperial policies of the minority world or were subjugated by them

Minority world: is constituted by the small number of economically advanced economies

Outside of the box: refers to approaches that question the taken for granted aspects of mainstream thought

Positivist: is the position that the social world can be studied in the same way that we study the natural world – we can explain what happened through causal laws/generalizations that are derived from observation and measurement

Post-Colonial Theory: embeds contemporary global politics in a history of imperial and colonial policies, where economically

Post-positivist: is the position that the social world cannot be studied in the same way as the social world because people are not chemical reactions

Poststructuralism: deconstructs how global politics privileges the minority world and seeks to empower the plurality in the majority world to define for themselves what constitutes equitable and just political, economic, and social systems

World Systems Analysis: takes global capitalism as the main unit of analysis and looks at the world capitalist system's historical development.

References

Brown, Chris. Understanding International Relations. Fifth ed. 2019.

Cole, James. “On Post-Structuralism's Critique of IR.” E-IR, May 14, 2013. https://www.e-ir.info/2013/05/13/on-post-structuralisms-critique-of-ir/.

Cox, J. Robert. “Memory, Critical Theory, and the Argument from History.” Argumentation and Advocacy 27.1 (1990): 1-13

Crawford, Neta C. “United States Budgetary Costs and Obligations of Post-9/11 Wars through FY2020: $6.4 Trillion”, Nov 13, 2019. The Watson Institute. Boston University.

Embury-Dennis, Tom. “US, Saudi Arabia and Uganda Join Forces to Declare Women Have No Intrinsic Right to Abortion.” The Independent, October 24, 2020.

Finnemore, Martha, and Sikkink, Kathryn. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change.” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 887-917.

Goodin, Robert E. Green Political Theory / Robert E. Goodin. Cambridge, Uk: Polity Press, 1992.

Keating, Joshua E. “Why Is the IMF Chief Always a European?” Foreign Policy. Foreign Policy, May 18, 2011.

Kinsella, Helen M. “Feminism” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations. edited by Baylis, Owens, and Smith. Eighth ed. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Koopman, Colin, 2013, Genealogy as Critique: Foucault and the Problems of Modernity, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

March, James G., and Johan P. Olsen. “The Institutional Dynamics of International Political Orders.” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 943-69.

Schouten, Peer. Theory Talk #37: Robert Cox, March 0, 2010. http://www.theory-talks.org/2010/03/theory-talk-37.html.

Thelwell, Kim. “Majority World.” The Borgen Project. January 26, 2020. https://borgenproject.org/tag/majority-world/.

Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice. The Modern World-system. Studies in Social Discontinuity. New York: Academic Press, 1974.

Wendt, Alexander. “Anarchy Is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics.” International Organization 46.2 (1992): 391-425.

Wendt, Alexander. "Constructing International Politics", International Security 20, no. 1 (1995): 71-81.

Supplementary Resources

Aydin-Düzgit, Senem. "Post-Structural Approaches and Basic Concepts of International Relations." Uluslararasi Iliskiler = International Relations 12, no. 46 (2015): 153-158.

Hopf, Ted. "The Promise of Constructivism in International Relations Theory." International Security 23, no. 1 (1998): 171-200.

Silva, Marco Antonio De Meneses. "Critical Theory in International Relations." Contexto Internacional 27, no. 2 (2005): 249-82.