When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the utility and limitations of applying the levels of analysis framework

- Understand when and how to apply the system-level of analysis to global politics

- Understand when and how to apply the state-level of analysis to global politics

- Understand when and how to apply the individual-level of analysis to global politics

Mingst, McKibben, and Arreguin-Toft. “Ch 4 Levels of Analysis”, Essentials of International Relations 8th ed. New York: W.W. Norton Co., 2019

- ‘Levels of Analysis’

- Systemic Level Analysis

- State-Level Analysis

- Individual-Level Analysis

- Polarity

- Unipolarity

- Bipolarity

- Multipolarity

- Balance of Power

- Internal balancing

- External balancing

- Bandwagonning

- Mutually Assured Destruction

- Multilateralism

- BlackBox

- Two-Level Game

- Complex interdependence

- Mutually Constitutive

- Securitization Theory

- Norm Entrepreneurs

Learning Material

In modules 1-3, we introduced global politics in broad strokes. We covered the four defining debates in the field, the status-quo theories that seek to explain contemporary global politics, and the outside the box approaches that challenge the mainstream theories. This module will use this broad introduction to begin analyzing global politics in a narrower and more nuanced way. One way to do this is to break down global politics by using the ‘levels of analysis’ approach.

As you might have already noted, global politics is complex, with a lot of different variables. Some issues are truly global in scale, like climate change or the COVID 19 Pandemic, with every person on the planet affected, albeit to different degrees. Some problems seem eternal, like the scourge of war and quest for world peace. Some issues are more local but with global implications, like the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor accident in 2001 or Cherynoble in 1986. Some are more regional, like the impact of Saudi Arabia Irian rivalry on the Yemeni civil war.

Figure 4-2: Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/question-mark-policy-problems-2546113/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

The ‘levels of analysis’ approach provides a means to begin parsing these issues by suggesting different types of questions to ask and highlighting different explanatory variables. For example, how can we explain the failure to achieve meaningful change in global climate change? We could look at systemic-level variables, such as the anarchical nature of global politics and the difficulty in ensuring sovereign states live up to their commitments, especially if they run counter to their national interest. We could look at national-level variables, such as the influence of corporations and/or sectoral interest groups that lobby their respective governments to oppose global environmental agreements. We could look at individual-level variables, such as the impact of particular state leaders on national policies regarding climate change, like US President Donald Trump or Chinese President Xi Jinping. This is by no means an exhaustive list of approaches to studying global climate change. Still, it does illustrate the three levels of analysis we are looking at: the systemic level, the state level, and the individual level. This module will introduce these levels of analysis and link them to the status-quo and outside the box approaches to global politics introduced in modules two and three.

In order to understand the systemic level approach to global politics, we need to understand the two meanings of systemic.

- The first use of systemic refers to the scope of analysis. In this sense, a systemic level of analysis examines all those explanatory variables that are operative everywhere, on all actors, including states, institutions, MNCs, and global civil society organizations. It is a top-down and structural approach that enables or constrains actors’ behaviour.

- The second use of systemic refers to the totality of something, constituted by many different parts and/or actors. Notably, this excludes looking at domestic or regional variables as they are parts of the whole.

An excellent example of a systemic level explanatory variable is anarchy. As a reminder, the definition of anarchy is the absence of any legitimate or supreme overarching authority. Since there is no legitimate authority above the sovereign state, global politics is anarchical. This holds true for every actor, even if anarchy constrains or enables respective actors, especially states, differently. For example, the US, China, Canada, Nepal, and Paraguay are all sovereign states. However, their respective differences in resources and power, as well as geographical and historical context, mean they have differing capabilities in dealing with the consequences of anarchy. Therefore, anarchy is ‘systemic’ in terms of scope. Anarchy is also systemic in the sense that it refers to a system constituted by many different parts. These include sovereign states, intergovernmental institutions, MNCs, NGOs, religious organizations, social movements, and other international actors. It also includes international law, agreements, norms, and practices. Therefore, their actions are constrained or enabled by the form and function of the anarchical system.

While briefly mentioned above, a systemic level analysis excludes the internal or domestic characteristics of states. It excludes the perceptions and actions of particular individuals. For a systemic level analysis to be consistent, it must meet the two criteria stated above: it must be truly global and refer to something’s totality. However, in practice, different approaches to global politics focus on different systemic-level variables. Therefore we will turn to how our mainstream theories and outside-the-box approaches operationalize the systemic level of analysis in global politics differently.

Figure 4-3: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/background-data-network-web-3228704/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of sumanley.

Realism

While we started with Liberalism in module two, we begin here with Realism. This is because it was a Realist theorist, Kenneth Waltz, who popularized the ‘level of analysis problem’ in global politics in his foundational book, Theory of International Politics. (1979) Waltz sets out the basic argument of Neo-Realism:

State Behaviour = Non-Differentiated Units + Anarchy + Capabilities

State Behaviour = Non-Differentiated Units + Anarchy + Capabilities

Therefore: State Behaviour = Capabilities defined in terms of the distribution of resources

As a quick review, Waltz argues this is true because:

- Global politics is anarchical, and therefore there is no higher authority to police the system above sovereign states

- The anarchical nature of global politics means that sovereign states must rely on themselves, or in other words, self-help

- Self-help means that states must act prudently to ensure their security, and this often translates into power-seeking behaviour

An essential corollary to this argument is that we cannot explain outcomes in global politics by looking at the system’s parts. Waltz argues this is ‘reductionist’ and cannot account for global politics’ broad historical patterns. This position excludes looking at individual states/institutions or their internal characteristics. For example, if we look at the USSR and the US during the Cold War, each state behaved in remarkably similar ways, despite their vastly different national and individual constructs. Neo-Realism argues this is because both states were struggling under the systemic-level variable of anarchy. Therefore, their difference in their national political ideologies, economy, and leaders didn’t matter. Hence, for Waltz, the only appropriate level of analysis in global politics is the systemic level, and more specifically, capabilities defined as the distribution of resources within the system.

Figure 4-4: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reagan_and_Gorbachev_signing.jpg#/media/File:Reagan_and_Gorbachev_signing.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of White House Photographic Office.

Figure 4-5: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:US_and_USSR_nuclear_stockpiles.svg#/media/File:US_and_USSR_nuclear_stockpiles.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Fastfission.

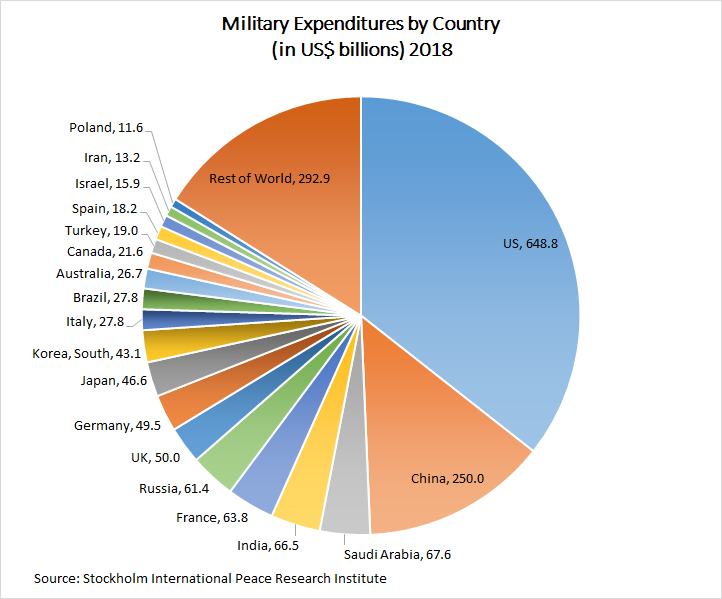

In general, realists privilege the systemic level of analysis and focus on questions of capability distribution and polarity. As noted above, the system’s distribution of resources determines a state’s capabilities and therefore defines appropriate state behaviour. Remember the adage, the strong do what they want, and the weak do what they must. When the distribution of resources is stable, there is order and predictability in the system. States are more secure in knowing what they can and cannot do. It is easier to predict the consequences of particular policy choices. However, when the distribution of power changes, the system is less stable, and there is less predictability. If one actor gains power, a Realist would argue other actors must seek to reestablish stability by finding a ‘balance of power’, either through internal or external balancing. Internal balancing means increasing hard power by increasing military capabilities, for example, with a larger army or new weapons. External balancing means forming alliances of convenience to counter the rise of another state. For example, a rising China or Russia might increase pressure for other states to increase their hard power or build/strengthen alliances. Suppose a state’s increase of power is precipitous or threatening to smaller states and that neither internal nor external balancing is possible. In that case, smaller states may choose to ‘bandwagon.’ Bandwaggonning is a policy whereby states seek security guarantees with stronger states or even the state they are threatened by, at the cost of compromising their sovereignty. In all three cases, a Realist would argue it is not the leader or national level variables that determine appropriate policy – it is the distribution of capabilities and potential instability at the systemic-level.

Figure 4-6: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Military_Expenditures_2018_SIPRI.png#/media/File:Military_Expenditures_2018_SIPRI.png Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Barnhorst.

Realists also focus on the polarity of the system. The international order can be unipolar, whereby one state, a hegemon, dominates global politics in terms of power. For example, there was a brief unipolar moment in 1989 when the USSR dissolved, leaving the US as the predominant power. The international order can be bi-polar. In a bi-polar system, two states or coalitions of states standing in opposition to each other hold a preponderance of power. For example, the Cold War was a bipolar construct, with the US and the USSR squared off against each other with their respective allies. This was most notable in the stand-off between the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Warsaw Pact. Finally, the international order can be multipolar, with the distribution of power spread across more than two states. For example, in the 19th-century Concert of Europe, Great Britain, Russia, Prussia, France, and Austro-Hungary worked together to balance power across the five states. It is also interesting to note that in the early 21st-century may be moving to a multipolar world.

Realists focus on polarity because they argue each configuration of power has significant consequences for system management and stability, translating into order or conflict. A unipolar world requires the hegemon to define, build, and maintain the international order at their own cost, but also to their benefit. And such a unipolar world can be orderly and prosperous since it is efficient and easy to understand. But they also tend to be unstable as new powers seek to challenge the hegemon, and the cost of maintaining hegemony can undermine the ability to do so. Unipolar constructs can also breed injustice and resentment, leading to instability, since the hegemon will privilege order and its national interests above equity and collective interests.

Some Realists argue a bi-polar world is the most stable and, therefore, the most conducive to order and peace. A bi-polar construct allows for power to be checked by the tension between the two states or coalitions. It will enable the system to balance more easily since each side can identify and counter gains by the other side. However, it can also concentrate power into two contentious blocs that see the other as existential enemies. The possible consequences of such an existential conflict could include global war, including thermonuclear war, by choice or by accident. It seems unlikely that two states would choose to unleash nuclear weapons because of the threat of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). However, there have been times where it came unnervingly close: the Cuban Missile Crisis, Israel in the Yom Kippur War, India-Pakistan conflicts, and the continual threat by North Korea to unleash its arsenal on the US and South Korea, for example. There are also frightening accounts of the US and the USSR almost starting a nuclear war by accident, through technical errors, or the failure of command and control mechanisms.

Figure 4-7: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NATO_vs._Warsaw_(1949-1990).png#/media/File:NATO_vs._Warsaw_(1949-1990).png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Chronus.

Figure 4-8: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BalanceOfPower_(cropped).jpg#/media/File:BalanceOfPower_(cropped).jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Finally, Realists argue a multipolar world is the most unstable system. This is because it includes more uncertainty and makes balancing more difficult. Balancing in a multipolar system requires a consensus amongst enough strong states to maintain the status quo, which requires a consensus on the system’s normative basis. For example, the Great Powers in the Concert of Europe maintained peace and order through a balance of power between 1814 and 1914. But in 1914, after the Concert broke down, the result was World War One. For Realists, in the end, polarity is a very consequential systemic variable of global politics.

Liberalism

While Liberal approaches to global politics do not privilege the systemic-level to the extent that Realists do, it is still a central concern. However, Liberalism’s understanding of global politics is more complex as they admit to more actors, address more issues, and recognize the interconnectedness of global politics. In terms of actors, Liberalism acknowledges the privileged role of the state. However, Liberals also recognizes the importance of international organizations, MNCs, NGOs, and global civil society more generally. In terms of issues, Liberals keep security as a core concern. However, they also privilege economic interests, social/identity concerns, and institutions’ capability to foster cooperation. In terms of global interconnectedness, Liberals argue the state is not monolithic but rather is constituted by a myriad of actors who may or may not agree with the national interest as defined by the government in power. They may even share more interests in common with foreign actors than their government. For example, a resource company in Canada and one in the US might share a positive view of a particular pipeline project, while the US or Canadian government might not. Out of the Liberal’s more complex view of global politics, three systemic-level insights emerge.

First, given the anarchic but interconnected nature of global politics and the breadth of issues and actors involved, Liberal approaches argue there is a strong need for multilateralism. Multilateralism is defined as three or more states working together on a specific issue. Multilateralism can be quite narrowly defined, for example, the many multilateral efforts to deal with specific issues like trade through NAFTA or the collection of states and NGOs that banded together to ban landmines. However, multilateralism can be a systemic-level effort, for example, the principle of collective security in the United Nations or efforts to address climate change through the Paris Climate Agreement.

Figure 4-9: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/presidenciamx/23430273715/ Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Presidencia de la República Mexicana.

Second, Liberal approaches to global politics see the international order as having a particular set of ordering principles. The Concert of Europe was an international order that centred on the idea of European stewardship. The ordering principles included a conscious and institutionalized effort to balance the system through Great Power stewardship as well as privileging the position of these powerful states in the world. It was supported by the burgeoning diplomatic system that sought to negotiate solutions to conflicts between these powerful states and institutionalize their interaction through regular meetings. The post-world-war two international order is characterized by liberal ordering principles that focus on institutions’ role in global politics, universal membership ideals, the building of economic interdependence, and support for individual rights. These ordering principles are not arbitrary, nor a result of anarchy, but the result of policymakers’ conscious and deliberate effort. For Liberal theorists, these ordering principles define systemic-level principles of global politics.

Figure 4-10: Membership in the World Bank Group. Source:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_Bank_Group.png#/media/File:World_Bank_Group.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Alinor.

Third, neoliberal institutionalists see institutions as a systemic-level prescription to the potential for conflict in an anarchic system. Neo-liberal institutionalists recognize the anarchic nature of global politics. They also recognize the potential for short term conflicts of interest that can lead to disorder and war. However, they differ from Realists in that they believe that the anarchic system isn’t necessarily conflictual and that there are more gains to be had from cooperation than conflict. The problem is finding a way to bring actors together, negotiate collective solutions to problems, monitor compliance, and apply penalties for breaching agreements. For Liberals, institutions can provide solutions to these problems and facilitate a shift at the systemic level from being predominantly or potentially conflictual to mostly or potentially cooperative. Further, they argue that overtime, this institutionalization of cooperation leads to interdependencies that make defection more costly and leads to the normalization of cooperation.

Figure 4-11: UN General Assembly. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:UN_General_Assembly_hall.jpg#/media/File:UN_General_Assembly_hall.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Patrick Gruban.

Outside the Box Approaches

Constructivism, Critical Theories, and Post-structuralism do adopt some systemic-level analysis. However, the roots and focus of these approaches often start at the state or individual levels of analysis. This contradicts Waltz’s proscription against reductionist approaches. Yet, it is worth applying outside-the-box insights at the systemic-level.

Constructivists argue the systemic level of global politics, like all other political arrangements, is defined and given meaning through social interaction and historical context. As such, Constructivism challenges the naturalized assumptions of global politics made by Realism and Liberalism. The state, sovereignty, anarchy are not natural. They don’t exist independent of human thought. Instead, they are ideational and are given meaning through social interaction. More specifically, these are European constructs that emerged out of the 15th Century Religious Wars, the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), the Congress of Vienna (1815), the Treaty of Versailles (1919), the League of Nations (1919-1946), and the post-war liberal international order (1945-?), to name a few big moments. As a socially constructed system, we derive much of the meaning we attach to global politics through social or ideational structures. Thus, they posit that the vast majority of our decision making occurs through a logic of appropriateness – adhering to expectations held of ourselves and held by others, based on the socially constructed roles that we occupy. This is true for institutions, regimes, states, MNCs, NGOs, and even individuals. Therefore, from a constructivist perspective, the systemic-level of analysis has deeply embedded role expectations that structure the form and function of global politics.

Figure 4-12: Globe Slide Come Closer. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/globe-slide-come-closer-approaching-3335589/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Critical Theories include a variety of approaches, but many take note of systemic level processes and structures. Critical Theories seek to contextualize global politics, understand how power frames its form and function, and privileges emancipation. In module three, we introduced three strands of Critical Theory: Marxism, Feminism, and Environmentalism. Each of these strands, to a greater or lesser degree, suggests systemic processes at work. Marxism, when applied globally, notes the impact of class through imperialism. The anarchic structure of global politics allows the rich and powerful to dominate and exploit the poor and weak. The capitalist basis of the global economy further encourages this exploitation. Even the Marxist solution to this exploitation is global: ‘workers of the world unite!’. Dependency Theory and World Systems Theory further develops the systemic-level impact of global capitalism through the Marxist lens of class. Feminist theories identify the role patriarchy plays in global politics, the global economy, and global social norms. They seek emancipation by creating space at the global level for the authentic voices of women. Similarly, Environmentalism identifies the anthropocentric role of human beings in dominating the global environment. They further identify how this domination occurs through capitalism and state sovereignty and its facilitation by capitalism and individualism. Environmental approaches to global politics seek emancipation through ecologically based policymaking. All of these Critical Theories identify systemic-level processes and constructs which privilege some to the detriment of others.

Figure 4-13: Source: https://flic.kr/p/6CzR7N Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Juriaan Persym.

Figure 4-14: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_Economic_Forum_logo.svg#/media/File:World_Economic_Forum_logo.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of World Economic Forum.

Post-structuralism posits that the taken for granted nature of important systemic concepts like anarchy, the state, sovereignty, or capitalism is a means by which the powerful have legitimated a system rigged to privilege their interests. The key for a post-structural analysis of these systemic-level concepts would be to deconstruct the processes that have led to their naturalization. This naturalization occurs through the privileging of particular truths and the gate-keeping of ‘legitimate knowledge’ by elites. Examples of this process are legion. Think of the World Economic Forum, held every January in Davos, Switzerland. At these annual summits, the elites of the minority world gather to discuss best practices in global capitalism and how best to solve issues like global poverty and global inequality. However, these conversations rarely include voices or perspectives from the majority world and outside some blue-sky thinking that has no chance of being adopted, rarely challenges global economic orthodoxy. Instead, these summits reinforce who is an expert, what constitutes legitimate knowledge, and establishes economic ‘truth.’ Post-structuralists would seek to deconstruct these processes and concepts, challenge orthodoxy, and denaturalize that which is taken as given. In so doing, new spaces may open, new voices could be heard, and subjugated discourses/alternate truths challenge the status quo.

The systemic-level of analysis focuses on those aspects that are truly global. Things like anarchy, which defines the global level. Or things like global capitalism, which is different than capitalism embedded in particular states. For Structural Realists, the systemic-level of analysis is the only appropriate level. As Waltz argued, anything else would be reductionist. For other approaches, the systemic-level of analysis is important but not paramount. Liberal approaches focus on the need for multilateral policymaking, for recognizing the particularities of different international orders, and the role of institutions in seeking to pacify the potential for conflict in an anarchical system. The outside-the-box approaches to global politics also recognize the importance of systemic-level processes and structures. Constructivism looks to the social construction of concepts and the meaning attached to them, like anarchy. Critical theories identify particular systemic processes, for example, imperialism, global capitalism, patriarchy, or anthropocentrism. And Post-Structuralism deconstructs the taken-for-granted aspect of many systemic concepts and processes, seeking to open the discussion to other subjugated discourses. In the end, the systemic-level suggests that some questions can be best answered, or more contentiously only answered, at the global level.

The state constitutes the second level of analysis. Most people would say they know what a state is, but many may have difficulty defining it. A state is a political entity with a defined territory, a given population, and a centralized government recognized by other states. Moreover, the state is a privileged actor in the current international system in that it has a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. It can use violence to enforce compliance with domestic laws. It has the right to use violence to defend its borders. The state also has legal personality in international law. Representatives of the state can enter into negotiations with other states, join international organizations, and sign treaties or otherwise commit their state to particular agreements. Unlike the anarchical system, the state is a hierarchical structure. It has an overarching authority and differentiated roles within the state, often specified in constitutions. State leaders, or the government in power, must play a two-level game. One level is domestic, where the government must negotiate with domestic actors to support their policies. Surprisingly for some, this holds true for both democracies and non-democracies. Democracies need public support to maintain power in the next election. Non-democracies must often maintain the support of other actors, such as oligarchs or competitors that may challenge the government’s rule. The other level is international. Governments must seek to achieve their foreign policy goals amongst other self-interested states seeking to achieve their own, often incompatible, foreign policy goals.

Take Canada, for example. The Canadian state is a constitutional monarchy, with the separation of powers and jurisdiction stipulated in the Constitution. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms establishes the respective set of rights and obligations between the Canadian state and Canadian citizens. The Canadian state needs to negotiate competing broad domestic interests, such as economic policy and environmental policy, but also regional cleavages, like the resource sector in the west and the manufacturing sector in the east. However, the Canadian state also needs to compete with other states to achieve the national interest as defined by the government. This includes dealing with the US, Canada’s largest trade partner and most important security ally. It includes negotiating access to important markets like the EU and China. And it includes, most generally, efforts to secure Canadian influence in the world.

Figure 4-15: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Political_map_of_Canada.svg#/media/File:Political_map_of_Canada.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Hogweard.

Figure 4-16: Flags Russia USA. Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/flags-russia-usa-germany-china-1722052/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of sinisamaric1.

A state-level analysis starts from the premise that the system cannot explain everything in global politics. For example, systemic-level analysis struggles to explain why similarly constituted states often react in divergent ways to similar conditions. For example, why would Costa Rica choose to abolish its military while neighbouring states, such as Nicaragua, Honduras or El Salvador, choose to spend a significant percentage of GDP on military spending? Why do Canada and the US have the world’s longest undefended border while the Pakistan-India border is considered the most dangerous border in the world? A state-level analysis would consider each state’s type of government. Were they democracies? Authoritarian states? It would look at the degree and kind of economic activity in each state. Is one state richer or poorer than the other? To what degree are their economies integrated? It would look at the cultural markers in each state. Do they share similar values? Do they have similar histories? Do they have a history of positive or negative interaction with each other? To make sense of a state-level analysis, it is useful again to turn to the mainstream theories and outside-the-box approaches to global politics.

Realism

The state-level of analysis in Realism is both simple and complex. At a basic level, Realism is a state-centric approach to global politics. In an anarchical world constituted by self-interested and sovereign states pursuing potentially conflictual interests, the state can only count on itself – in other words, the state must rely on self-help. As sovereign states, they have absolute authority over their domestic affairs – their people, economy, culture, and values. However, the different variants of Realism account for the state differently. Structural or Neo-Realism is the most dominant variant, and it is, like all variants, a state-centric theory. However, Structural Realism has a very thin account of the state since the system’s distribution of resources determines appropriate state behaviour. This essentially makes everything inside the state irrelevant – all states with the same capabilities, facing the same threat or opportunity, should act the same. To do anything else would be to court existential disaster – remember the Melians. Hence, Structural Realism puts the state in a BlackBox, where no one knows or needs to know what is happening domestically. All that matters is systemic signals. If relative state capabilities and systemic signalling determine the correct policy choice, then the person making that choice, the form of government, and historical context are all unimportant. It is this parsimony that Realists consider a strength. It makes global politics predictable. However, what happens when Realism fails to predict significant events in global politics? Like the end of the Cold War?

The end of the Cold War was a massive shock to Structural Realist. Their analysis tended to look at the systemic level of analysis – to the balance of power between two superpowers. However, a state-level of analysis might have revealed the degree to which the USSR’s economy struggled to provide the means to compete with the US. It might have noted how the ideological element of the struggle between the US and the USSR perverted policy decision-making, encouraging each state to make riskier policy choices. In response, Neo-Classical Realism emerged. Neo-Classical Realism accepts the broad argument that the system determines appropriate state action, but it also recognizes intervening state-level variables that influence specific policy decisions. These state-level variables include the perception of state leaders, restrictions posed by state structures, the compliance of state elites, and societal factors that enable or restrict the mobilization of potential power into actual power. The differences between Structural Realism and Neo-Classical Realism demonstrate the uneasiness that Realists have with system-level analysis but also the struggle that Structural Realism has in explaining specific foreign policy decisions.

Figure 4-17: Fall of the Berlin Wall. Source: https://flic.kr/p/9eMG2 Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Gavin Stewart.

Liberalism

As we previously mentioned, Liberal approaches to global politics admit more complexity into their analysis. They address more global issues than just security. They recognize more actors than just the state. They see a deeper level of interdependence between actors. And, in the end, Liberals argue that global politics is not entirely structurally determined and that progress is possible through agency. At the most generic level, Liberals see the importance of state-level analysis through the idea of pluralism. In politics, pluralism is the idea that power is, or should be, dispersed amongst competing actors. These could be economic actors, social actors, cultural actors, et cetera. These actors compete for influence with the government, and Liberals argue this is normatively good as it avoids the concentration of power. To quote Lord Acton, “power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” This dispersal of power checks government overreach and provides individuals and groups with the potential to organize and advocate for their policy preferences. This argument suggests that the state should be a neutral arbiter of domestic policy preferences. When applying domestic pluralism to foreign policy, Liberals argue that the state is playing that two-level game introduced above. On one level, domestic debates between competing actors pressure the state to pursue specific foreign policies. On a second level, the anarchic nature of global politics means that states must pursue these policies in a competitive environment, with other self-interested states pursuing their own and perhaps incompatible policies. Therefore Liberals apply a system-level analysis to see how this tension between domestic pluralism and international anarchy influences foreign policy and the politics of global issues. For example, many states openly admit that climate change is perhaps the most existential threat we face today. So how do we explain the inability to address the problem effectively? Liberals would argue it can be explained, at least in part, by the influence of MNCs and other actors that see such policy as a threat to economic development. Therefore the failure to adopt meaningful global solutions to climate change, at least in part, can be explained through state-level analysis.

Figure 4-18: Source: https://flic.kr/p/br9u74 Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Kyle Pearce.

Another consequence of a pluralist view of domestic politics is that there will be differing definitions of the national interest. For example, people in the resource extraction, manufacturing, and financial services sectors may fundamentally disagree about Canadian foreign policy choices. Environmental groups may differ with international development groups on Canadian foreign policy spending or Canadian adoption of particular international agreements. One important consequence of this is that these groups may build transnational connections to pursue their policy preferences. Resource extraction advocates in Canada and the US, or in Australia for that matter, will likely have more in common than they would with many environmental groups in their own states. These groups may create formal or informal networks that lobby their own governments, their coalition members’ governments, and advocate through the various international institutions and other fora, like the WEF, for example. These transnational networks suggest that the idea of the state as a black box is misguided. Rather, the state is just one, albeit a privileged, actor in global politics. From a Liberal perspective, a better image is of complex interdependence, an idea first proposed by Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye in their 1973 article “Power and Interdependence.” They argue that the world is not constituted by a world of states with sharply delineated borders that mark sovereign territories. Instead, they see the world as being constituted by multiple channels of communication between numerous actors. They argue that security is but one of many goals that actors are pursuing and that the prioritization of issues is contextually specific. They conclude with an argument that hard power is becoming relatively less important, while economic power and soft power are becoming relatively more important. Therefore, complex interdependence suggests that state-level analysis is an essential lens to understanding and/or explaining global politics.

Finally, the state-level of analysis is central to the Liberal Democratic Peace Theory. We covered this in module 2, but as a brief reminder, the DPT argues that democratic states do not go to war with each other. While there are some exceptions that prove the rule, this maxim has generally held true. This does not mean democracies are pacifist; they are not. Nor does it prove that non-democracies are more aggressive, though they may be. But it does demonstrate that the state-level variable of government type has explanatory power in global politics.

Figure 4-19: Source: https://flic.kr/p/tdaFC Permission: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Sara.

Outside the Box Approaches

Constructivism, Critical Theories, and Post-structuralism all contain system-level analysis. For Constructivism, the relationship between the state and the system is mutually constitutive. Mutual constitution means that A does not cause B, nor does B cause A, rather A and B cause each other. Think of the master and slave relationship. (Please note, this is no way condones the practice, historical or otherwise, of slavery) You cannot be a slave without a master, and you cannot be a master with a slave. The two roles are mutually constitutive in that both need to be present for each role to exist. Therefore Constructivism posits state-level variables and systemic-level variables frame each other. The practices of states create particular international systems. In turn, the international system recognizes and legitimates the privileged role of states. This holds true for other global concepts like anarchy, sovereignty, and global capitalism. The meaning attached to these concepts is derived through actors’ social interaction, the most important being states.

Finally, Constructivism looks to state-level variables to understand and explain how meaning is generated. For example, a Constructivist explanation of the Cold War might look at the construction of animosity between the US and USSR. Each state believed they were involved in a righteous battle against an evil empire. Therefore the Cold War was deeply influenced by the meaning each party attached to themselves and the other: democratic capitalism vs socialist communism. These characteristics are state-level variables.

Figure 4-20: Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cold_War_TV_Series_CNN.jpg#/media/File:Cold_War_TV_Series_CNN.jpg Permission: Fair Use.

Critical Theories also adopt a state-level analysis of global politics. As a quick reminder, Critical Theories seek to contextualize the historical development of structures, critically assess the power behind these structures, and suggest practical means of emancipation for those who are marginalized or discriminated against. Marxism, Dependency Theory, and World Systems Theory, all adopt some form of class analysis that argues the capitalist economy of core states exploit peripheral states, often by co-opting elites in the periphery. Feminist approaches to global politics posit the intersection of patriarchy and capitalism institutionalizes discrimination against women. Environmental theories look to the exportation of anthropocentrism through western political, economic, and social norms. Each of these Critical Theories looks to state-level variables to explain global phenomena.

One Critical Theory that is more specific to the state-level analysis is Securitization Theory. Securitization Theory emerged out of the Copenhagen School of security studies and the work of Ole Weaver and Barry Buzan. Securitization Theory highlights how actors, most often the state, designate something as an existential threat and, if successful, are granted exceptional powers. Essentially, securitization allows states to do things not permitted by convention or law by identifying a threat to the state’s very existence, the national culture, or some critical aspect of the nation. Securitization theorists are highly critical of how states use ‘threat’, often quite strategically, to expand their reach. The Global War on Terror (GWOT) is an excellent example of securitization. Many states, but most specifically the US, have used the threat of transnational terrorism to infringe on civil liberties, allow more aggressive use of force internationally, and label opponents as existential enemies. However, Securitization Theorists would question the degree to which the GWOT poses an existential threat. Even more importantly, they would suggest that the GWOT is the perfect foil for securitization. How can a war against terror be won? Who is the enemy? Much like the War on Drugs that preceded it, the GWOT is an undefined enemy that allows perpetual threat and, therefore, an endless extension of emergency or exceptional powers. This is a state-level analysis since securitization will enable governments to expand their powers both domestically and internationally.

Figure 4-21: Source: https://flic.kr/p/kmyavc Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of @LIQUIDBONEZ.

Post-structural use of state-level analysis focuses on the concept of the state and the discourse involved in a particular state’s foreign policy. Post-structuralists often deconstruct and denaturalize the three Realist assumptions of the state: groupism, objective national interest, and the concept of power. First, Realists argue that the state is a natural extension of human survival instinct – that we organize in culturally defined polities to protect what is ours and extend our influence. In other words, groupism is about power. Post-structuralists agree that groupism, or the state, is about power but disagree that it is natural. Instead, they argue that the state is a construct sustained through historical practices that reifies western norms and privilege. By delineating a sharp inside-outside distinction, groupism is a discourse that legitimates state power and reaffirms the need to support the state for fear of others. Second, Realists argue that the national interest can be defined objectively by the distribution of the capabilities in the system – stronger states do what they want, weaker states do what they must. Post-structuralists posit that the national interest is anything but objective. Instead, they argue the national interest is a discourse that naturalizes elites’ interests – that when the government claims this foreign policy is vital for the national interest of Canada or the US, they are actually legitimating the interests of elites within Canada or the US. Third, Realists suggest that the study of global politics is the study of power defined by material capability, military capacity, for example. Post-structuralists also recognize the centrality of power, but they define it as discourse. They argue that power as discourse is a more pervasive form of power. For example, which is more powerful, being forced to do something by threat or being convinced that doing something is right and in your own interest?

Figure 4-22: Silhouette of Four Person With Flag of United States Background. Source: https://www.pexels.com/photo/silhouette-of-four-person-with-flag-of-united-states-background-1046398/ Free to Use. Courtesy of Brett Sayles.

Post-structuralism applies state-level analysis when deconstructing the narrative of particular foreign policy choices. As discussed in module three, Post-structural analysis leans extensively on the role of language and how language constructs meaning through discourse. When states adopt particular foreign policy choices, they must defend why this choice is legitimate. A legitimate foreign policy will identify a problem or opportunity, an appropriate policy response, and explain why this is the best policy to adopt. These explanations are embedded in particular discourses, like making the world safe for democracy, a discourse used by Woodrow Wilson to legitimate entry into World War One, and George Bush to legitimate the GWOT. A Post-structural analysis would deconstruct the discourse of making the world safe for democracy. What states are democracies, and what states are not? How would war make the world safe for those states deemed democracies? Are there specific interest groups within those democracies that will benefit from war? Are there subjugated discourses that are being silenced? If so, why? What are those subjugated discourses? Whose interests are served by those subjugated discourses? How do those subjugated discourses challenge the dominant discourses? In the end, what does this tension between dominant and subjugated discourses tell us about the role of power and interests in the state?

The state-level of analysis examines how differences in state form and state action have a significant impact on global politics. Questions on state form include its political, economic, and social organization. For example, does it matter if a state is democratic or communist? Does it matter if two states have significant trade relations? How can we explain why similar states, facing similar circumstances, make different policy choices in terms of action? Or how can we explain states who fail to act predictably to systemic signals? In many ways, the state-level of analysis fills gaps that emerge in systemic-level analysis. For example, Structural Realism’s failure to predict the end of the Cold War led to Neo-Classical Realism, which included the systemic and state levels of analysis. Liberalism takes state-level analysis much more seriously. Liberalism explores the impact of pluralism and the requirements of playing a two-level game on global politics. It questions the BlackBox image of Realism, suggesting global politics is typified by complex interdependence. The Democratic Peace Theory indicates that the form of government has a significant impact on global politics. Critical Theory, and more specifically Securitization Theory, suggests that the state uses global threats to maximize its power domestically and complicates global cooperation. Finally, Post-structuralism deconstructs and denaturalizes assumptions about the state in global politics and the discourses used to legitimate specific foreign policy decision making. In the end, state-level analysis suggests that there is analytical utility, if not at times a necessity, to appreciate how variation in state form and state action impact global politics.

The third level of analysis looks at the role of individuals, usually leaders, in global politics. Before the study of global politics emerged as a distinct discipline, the individual level of analysis was quite common. It was rooted in the study of history and diplomacy, often looking at particular events, countries, or processes. This is the ‘Great Men’ of history thesis – not that women were unimportant, but the term reflects men’s privileged role in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This is the history of Kings, Queens, Emperors, and Conquerors. As the 19th-century British thinker Thomas Carlyle argued, the “history of the world is but the biography of great men” (2015). In the early to mid-20th century, the ‘Great Men’ of history thesis was less influential, albeit still there. Hans J. Morgenthau, the father of Classical Realism, argued that a scientific study of global politics negates the need to account for an individual-level of analysis since it is “consistent with itself, regardless of the different motives, preferences, and intellectual and moral qualities of successive statesmen” (1960). The question is whether it was Napoleon, Lenin, Churchill, or as a Canadian example, Lester B. Pearson that was responsible for great things or were they merely in the right place at the right time? The answer is likely both. There is no question that Napoleon or Stalin influenced the Napoleonic Wars or the Russian Revolution. However, their ability to influence history was also a product of context – economic, political, social shifts that opened space for them to act. In the end, this is more of a question for history than it is for the general study of global politics. However, there is still one question pertinent to us – under what circumstances are individuals likely to exert more significant influence? This is important because, most often, especially in mature democratic states, government structures prevent any one person from exerting a more substantial influence on state policy. For example, the election of Donald Trump as President in 2016 created a fair amount of chaos in American politics. However, this chaos was mostly due to ignoring political conventions, or normative expectations, of the President. For the most part, the institutions of the US government constrained the erratic impulses of President Trump. However, there are times when things align to facilitate the individual’s ability to affect significant change. First, in times of crisis or when political institutions cannot respond adequately to current events, leaders may exert more significant influence. For example, the Great Depression opened a window for Franklin D. Roosevelt to pass the New Deal. Second, leaders have more room for agency when the institutions of the state are weak. For example, in authoritarian states like Russia or China, Putin and Xi can exercise a considerable degree of policy discretion. Third, leaders can sometimes exert significant influence, even in mature democracies, when they focus exclusively on a narrow set of goals, the issue is peripheral, or the situation is novel. For example, German Chancellor Angela Merkel accepted 1.7 million refugees between 2015 and 2019, most from the Syrian Conflict. Merkle encountered significant domestic resistance, albeit mostly after the fact. However, the unprecedented nature of the Syrian Conflict, the immediacy of the refugee flows on the border of Europe, and most of all, the willingness of Merckle to spend political capital on the issue facilitated her unprecedented action. Yet, as we will see in the next section, the individual level of analysis is the least important for studying global politics.

Figure 4-23: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2015.09.02.-Menek%C3%BCltek-a-Keletin%C3%A9l-01.jpg#/media/File:2015.09.02.-Menekültek-a-Keletinél-01.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Eifert János.

Realism

Realists pay little attention to the individual level of analysis, especially Structural Realists. Looking back at history, Classical or Neo-Classical Realists may analyze the skill of leaders like Austrian Chancellor Metternich in establishing the Concert of Europe at the Treaty of Vienna, 1815, or the ability of European statesmen in maintaining the Concert until World War One in 1914. Yet, this is tangential to a Realist analysis, which focuses on the role of power and the system’s distribution of capabilities as the prime determinant of appropriate state behaviour. The individual only comes into a Realist analysis when leaders manifestly fail to heed systemic signals and put their state at risk – again, like the Melians.

Liberalism

Liberals do attach more importance to the role of the individual in global politics. And this makes sense given the core Liberal argument that progress is possible in global politics through the privileging of the individual and the application of inherent reason and rationality. The individual-level also comes into play with the Liberal focus on the role of pluralism in politics. Pluralism does put some explanatory power on the ability of individuals and groups to set the government’s foreign policy agenda. But, much like Realism, the individual-level is more peripheral for a Liberal analysis of global politics. While rhetorically engaging with the importance of the individual and human rationality in facilitating peace and prosperity, the individual-level of analysis is not a central focus of Liberal approaches to global politics.

Outside the Box Approaches

Neither Critical theories nor Post-structural approaches significantly develop an individual-level analysis of global politics. Instead, they critique or deconstruct structures that privilege some to the detriment of others. This critique or deconstruction is undoubtedly focused on benefiting individuals, often the masses versus the elites, but their analysis is at the state level. One minor caveat is that Post-structural approaches may deconstruct discourses around particular cults of personality. However, the focus is still more on the process and impact than the specific individual.

Figure 4-24: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Committee_of_Five_Geneva_1863.jpg#/media/File:Committee_of_Five_Geneva_1863.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Constructivism, however, takes the individual level of analysis more seriously. Constructivism seeks to explain the social generation of meaning between actors and how that influences the form and function of global politics. Implied in this analysis is the idea of change: how do ideas change? Why was slavery once an acceptable practice? What made it unacceptable? Constructivists look to norm entrepreneurs to challenge existing structures, norms, and practices. Norms represent accepted practices as well as what is considered good and right. They exist in a cycle that starts with norm generation, norm cascades, and finally internalization. If successful, new norms begin to establish a new logic of appropriateness. Norm entrepreneurs are individuals or groups who shepherd this process of normative change. They advocate for new norms in public. They apply pressure on policymakers. They facilitate the adoption and internalization of norms. For example, after experiencing the horror of war at the Battle of Solferino (1859), Henri Dunant advocated for norms on the conduct of war, the rights of the wounded, and other human rights. This led to the creation of the Red Cross, which then led to the Geneva Conventions. Norm entrepreneurship is an individual-level process that has a significant impact on global politics.

The individual-level of analysis looks to the role that people, most often leaders, have on global politics. Prior to the study of global politics as a distinct field of inquiry, the individual-level of analysis was quite common. This analysis was more a study of diplomatic history or the history of the Great Men of history. However, the individual-level of analysis is much less used in most theories of global politics. Realism, Liberalism, Critical Theory, and Post-structuralism only tangentially apply the individual-level. Constructivism is the one exception. As Constructivism seeks to explain change in global politics, they introduce the concept of norm entrepreneurs – individuals and groups who work to challenge existing ideas of acceptable practice, and replace them with new norms that establish a new logic of appropriate behaviour. In the end, the individual-level of analysis is the least adopted of the three introduced. However, Constructivism does suggest that individuals have the capability to be quite influential.

The levels of analysis approach seeks to break down the complexity of global to identify where questions of global politics can best be answered. The system-level suggests some questions are best answered at the global level. For example, why did the US and the USSR act similarly during the Cold War despite the significant differences in their political, economic, and social structures? For some, like Waltz, the system-level is the only appropriate level to explore global politics. He argues anything else is reductionist and therefore flawed. The state-level of analysis argues that the state is a privileged actor in global politics and, by extension, has a significant impact on its form and function. A state-level of analysis looks at state types, economic systems, cultural context, and history to see how that influences global politics. For example, what is the significance of democracy on global politics? The individual-level of analysis suggests that people, and most specifically leaders, have an impact on global politics. For example, what impact has the election of Donald Trump or Justin Trudeau had on the US and Canada’s respective role in global politics?

The levels of analysis approach can usefully be parsed through the mainstream theories and outside-the-box approaches to global politics. Realism mainly adopts a systemic-level of analysis as it focuses on the global distribution of capabilities. Yet, it does grudgingly admit state-level analysis to explain particular foreign policy decision making. Liberalism also adopts a systemic-level analysis but focuses more particularly on state-level analysis as it suggests that the state form, economy, culture, and history influences how states act. The logic of Constructivism can be applied at all levels of analysis as it is seeking to explain the generation of meaning through social interaction in any structure. However, Constructivists make a singular contribution at the individual-level of analysis through the concept of norm entrepreneurship. Critical theories primarily adopt systemic and state levels of analysis by focusing on how both global and national structures are often coercive. Further, Securitization Theory looks at how states use the rhetoric of existential threat to claim extraordinary powers in both domestic politics and foreign policy. Finally, Post-structuralism adopts the systemic and state levels of analysis by deconstructing discourses at each level that privilege some to the detriment of others. In the next module, we are going to address the defining feature of global politics, anarchy.

Figure 4-25: Woman in a white lace dress holding desk glove photo. Source https://unsplash.com/photos/8cZr8HUet7U Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Slava on Unsplash

Review Questions and Answers

Liberalism is most operative at the systemic and state levels of analysis. At the systemic-level, Liberalism notes that every system has specific ordering principles which influence global politics. They also privilege multilateralism and institutions as a means to address global issues. However, it is the state-level of analysis where Liberalism has the most refined argumentation. Liberalism uses the concept of pluralism and the logic of the two-level game to explain the tension decision makers face between the domestic and foreign. The Liberal variant, DPT, also suggests that the form of states has significant impact on the form and function of global politics.

Constructivism can be applied to all levels of analysis since it is identifying and assessing the impact of meaning generated through social interaction. This can be applied to constructs such as anarchy, democracy, and leader perception. However, Constructivism stands apart from other theories by using the individual-level of analysis and in particular the concept of a norm entrepreneur to argue the individuals and groups can play a fundamental role in global politics.

Critical theories are most operative at the systemic and state levels of analysis. In both cases, the goal is to contextualize the historical development of structures, critically assess the power behind these structures, and suggest practical means of emancipation for those who are marginalized or discriminated against. Using the approaches introduced in Module 3, we can see how Marxism, Feminism, and Environmentalism can operate at both the systemic and state levels. One stand out application of Critical Theory at the state-level of analysis is Securitization Theory, whereby the state rhetorically uses existential threat to claim extraordinary powers.

Post-structuralism can be applied at the systemic and state levels of analysis. At both levels, Post-structuralism deconstructs and denaturalizes discourses which stake truth claims on global politics. For example, the discourse of anarchy as threat or the taken for granted discourse of the state. In so doing, Post-structuralism seeks to identify and open space for subjugated discourses.

Glossary

‘Levels of Analysis’: suggests that some global politics questions are best addressed at the systemic level, state level, and individual level.

Systemic Level Analysis: looks at the systemic structures and processes that have a determinative role on the form and function of global politics, for example, anarchy or global capitalism.

State-Level Analysis: notes the privileged role of the state in global politics and looks at how different types of states, economic organization, cultures, and history have a determinative role on the form and function of global politics, for example, the impact of democracy.

Individual-Level Analysis: suggests that people, and more specifically leaders, have a determinative role on the form and function of global politics, for example, a Napoleon or Stalin.

Polarity: refers to the distribution of power within the global system.

Unipolarity: describes a system in which one state has an overwhelming concentration of global power.

Bipolarity: describes a system in which the distribution of global power is concentrated in two states or a coalition of states.

Multipolarity: describes a system in which the distribution of global power is diffused amongst more than two states.

Balance of Power: is a system where no single state or coalition of states can dominate others in the system

Internal balancing: occurs when a state builds up its own capabilities, most often military, in response to a perceived external threat

External balancing: occurs when a state works with other states to counter a perceived external threat

Bandwagonning: a choice by smaller states when faced with a threat to attach themselves to the foreign policy interests of a stronger state or even the threatening state

Mutually Assured Destruction: is a doctrine in which the use of particular weapons, like thermonuclear warheads, would result in a retaliatory strike and the subsequent annihilation of both parties.

Multilateralism: cooperation between three or more states on a particular issue

BlackBox: suggests that state and individual-level variables are irrelevant since systemic signals dictate state behaviour

Two-Level Game: suggests that state decision-makers must take domestic processes and issues in mind when defining and executing their foreign policy.

Complex interdependence: is the idea that states are not unitary actors but are instead connected through informal and formal channels of transnational networks.

Mutually Constitutive: is the idea that two variables require each other to exist but are not reducible to each other

Securitization Theory: argues that actors, most often states, may rhetorically label something as an existential threat in order to take on extraordinary powers not normally permissible under convention or law.

Norm Entrepreneurs: are individuals or groups who seek to challenge and replace existing norms.

References

Blair, Bruce. The Logic of Accidental Nuclear War. 1993.

Finnemore, Martha, and Kathryn Sikkink. "International Norm Dynamics and Political Change." International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 887-917.

Harper, John Lamberton. The Cold War. Oxford Histories. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Keohane, Robert O, and Joseph S Nye. “Power and Interdependence.” Survival (London) 15, no. 4 (1973): 158-65.

Morgenthau, Hans J. Politics among Nations : The Struggle for Power and Peace. 3rd ed. New York: Knopf, 1960.

Oltermann, Philip. “How Angela Merkel's Great Migrant Gamble Paid Off.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, August 30, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/30/angela-merkel-great-migrant-gamble-paid-off.

Schecter, Darrow. Critical Theory in the Twenty-first Century. Critical Theory and Contemporary Society. 2013.

Shavit, Yaacov. “Thomas Carlyle versus Henry Thomas Buckle: “Great Man” versus “Historical Laws”.” In The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz, 301. Waltham,

Stritzel, Holger. Security in Translation : Securitization Theory and the Localization of Threat. New Security Challenges Series. 2014.Mass Brandeis University Press, 2015.

Waltz, Kenneth Neal. Theory of International Politics. 1st ed. Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Supplementary Resources

Epstein, Charlotte. "Who Speaks? Discourse, the Subject and the Study of Identity in International Politics." European Journal of International Relations 17, no. 2 (2011): 327-50.

Gleditsch, Nils. "Peace and Democracy: Three Levels of Analysis." The Journal of Conflict Resolution 41, no. 2 (1997): 283-310.

Ray, James. "Integrating Levels of Analysis in World Politics." Journal of Theoretical Politics 13, no. 4 (2001): 355-88.