When you have finished this module, you should be able to:

- Define Foreign Policy

- Explain the difference between Foreign Policy Analysis and Global Politics

- Apply the tools of Foreign Policy Analysis

- Apply Graham Allison’s three models of foreign policy decision-making

- Recognize and apply the relevant aspects of theories of global politics to foreign policy cases

Alisson, Graham. “The Cuban Missile Crisis”, in Smith, Hadfield, Dunne. Foreign Policy: theories, actors, cases. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Breuning, Marijke. “Ch 7 Who or What Determines Foreign Policy”, Foreign Policy Analysis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Jackson, Robert and Georg Sørensen. “Foreign Policy” in Introduction to International Relations: Theories and Approaches, 5th Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Foreign Policy

- National Interest

- High Politics

- Diplomacy

- Economic Statecraft

- Military Force

- Foreign Policy Analysis

- Rational Actor Model

- Organizational Behaviour Model

- Governmental Politics Model

Learning Material

In this module, we pivot from global politics’ broad themes to foreign policy’s more immediate actions. Foreign policy, colloquially put, is everything actors do to secure their interests outside their borders. It is what the governments of Canada, the US, or Germany are doing in the Paris Climate Agreement. It is what Member States and UN bodies are doing in the Sustainable Development Goals. It is the diplomacy, economic policy, and use of military force used by states and institutions to enact agency in the anarchical system. However, with all that being said, it can be unclear who is doing what, why, how, where, and when. That is because foreign policy is often ad hoc and played out in secrecy. It is disconnected from people’s everyday lives. Citizens may approve o disapprove of what their or other states are doing, but it is rarely as immediate to them as domestic policy.

Therefore, in this module, we will define foreign policy as well as the study of foreign policy, or Foreign Policy Analysis. We will emphasize the deliberative nature of foreign policymaking, unpack the tension between structure and agency, and the influence of the two-level game on foreign policy. We will introduce and the tools available to foreign policy decision-makers. We will introduce Foreign Policy Analysis and the different analytical approaches it adopts, including normative analysis, the level of analysis approach, and domestic variables. We will focus specifically on Graham Allison’s deconstruction of the Cuban Missile Crisis and his three foreign policy analysis models: the Rational Actor Model, the Organizational Behaviour Model, and the Government Politics Model. Finally, we will close by looking at foreign policy through our theories and approaches to global politics.

Figure 7-2: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/handshake-understanding-3200298/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

For the average person, foreign policy is something done by the government in pursuit of the national interest. However, if asked what specifically is being done, by whom, and for what purpose, there would likely be less certainty. That is because foreign policy in most can seem entirely divorced from citizens’ everyday lived experience. The general public perceives foreign policy as the epitome of ‘high politics’, conducted by state leaders and senior bureaucrats behind closed doors. Foreign policy issues are seen as complicated, thus requiring expert knowledge. This stands in stark contrast to domestic policymaking, which has tangible impacts on citizens’ quality of life – for example, how much you pay in taxes, the types and number of jobs available, and access to healthcare. And everyone likes to armchair quarterback domestic policy.

However, while understandable, this public disconnect is unfortunate since everything the government does in terms of foreign policy is done in its citizens’ name. And this disconnect can be overstated since, at times, foreign policy does generate significant domestic debate. This makes foreign policy is very much a two-level game. State leaders and senior bureaucrats sit between the domestic consequence of their foreign policy choices and global politics’ anarchic nature. On the domestic front, foreign policy decision-making is not divorced from domestic consequences. When foreign policy poses a threat to particular interest groups, those groups will lobby both directly to the government and indirectly through public campaigns. For example, Justin Trudeau’s Government has enacted policies in order to meet international commitments to combat climate change, such as putting a price on carbon and cancelling several pipeline projects. This has generated direct and indirect efforts to change these policies, from provincial governments, resource extraction lobbies, and think tanks associated with these lobbies. This makes foreign policy decision-making high stakes domestic politics. Less risky but still potentially important are foreign policy decisions that depart from traditional policy orientations. For example, when the Government of Stephen Harper sharply veered away from traditional Canadian foreign policies on peacekeeping or involvement in the United Nations, there was pushback from some groups who saw this as a betrayal of ‘who we are’ as Canadians.

Figure 7-3: Source: https://flic.kr/p/cz5r95 Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Jamie McCaffrey.

While domestic concerns can complicate foreign policy decision-making, foreign policy’s implementation is complicated by global politics’ anarchical nature. Policymakers are pursuing the national interest, as defined by the government of the day, in an anarchical system constituted by other self-interested states doing the same. These other states may be stronger, or part of larger alliances and they might be pursuing policies running counter to policymakers’ perception of the national interest. For example, while many states, including Canada, rightfully criticized Russia’s annexation of Crimea, there was little direct action to be taken if those states were unwilling to risk a military confrontation with Russia. Russia perceived Crimea as very important to its national interest, and it is a state too big to force back with anything less than military action.

Figure 7-4: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2014-03-09_-_Perevalne_military_base_-_0162.JPG#/media/File:2014-03-09_-_Perevalne_military_base_-_0162.JPG Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Anton Holoorodko.

Therefore, foreign policy is plagued by complexity. It is opaque, ad hoc, and secretive. It is, at times, constrained by domestic political considerations and by the anarchical nature of global politics. Foreign policy decision-makers must look in both directions when creating and implementing policy. But this still doesn’t define foreign policy. However, we can start to define foreign policy by focusing on why it happens and the context in which it occurs. Policy of any kind, including foreign policy, is deliberate, meaning perceptions of threat and opportunity drive it. Decision-makers rarely wake up in the morning and decide to reorient their state’s foreign policy. Decision-makers are preoccupied with the vast number of policy areas and policy issues they need to monitor. What most often sparks a policy change or new policy is when they perceive an opportunity or threat to their state’s interests. Suppose a state is in a security dilemma, and they see an actual or potential enemy militarizing. In that case, political leaders will perceive a threat and may increase their own military capabilities, seek support from allies, or pursue security guarantees from stronger actors. The Cold War between the US and the USSR is a classic example of this logic, but so is the contemporary tension between Saudi Arabia and Iran and how that tension has played out in the conflict in Yemen. Conversely, suppose states see an opportunity to join a large and lucrative trade block. In that case, political leaders will perceive an opportunity, and if they believe it to be worth the cost, they will adjust their policies as required. The creation of the common market in the European Union is an excellent example of this logic, as are the subsequent enlargement rounds. Countries that wanted to join the EU in 2004, like Poland, had to align their domestic political, economic, and legislative policies with EU norms. They also had to agree to a common external trade policy and to coordinate defence and security policy. This is quite a demanding list of requirements that deeply impinge upon a state’s sovereignty. But if the benefits are perceived to outweigh the costs, they may be willing to do so. However, sometimes the perception of opportunity can lead to poor choices. For example, Turkey also sought to join the EU, but their bid was unsuccessful due to many factors. Moreover, this unsuccessful bid has had serious consequences for the relationship between the EU and Turkey. This, in turn, has had serious implications for western states, more generally in the region and more specifically in the Iraqi and Syrian conflicts. It is important to highlight some aspects of this discussion. Foreign policy is deliberative and driven by perceived threat and opportunity. It is most often pursued by the state, but other authoritative actors, like the EU or the UN, also have their own foreign policies. Foreign policy comes down to immediate decisions, but it also has medium and long-term consequences.

Figure 7-5: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EC-EU-enlargement_animation.gif#/media/File:EC-EU-enlargement_animation.gif Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Kolja21.

If we combine the points of the two-level game and the deliberative aspect of foreign policymaking, we start to approach an operational definition of foreign policy. The two-level game aspect contextualizes foreign policy. On the one side, these policies have direct material domestic considerations since they can impact particular interest groups. These policies can also have political considerations since they may influence voters. These policies have state identity considerations since there is an expectation that foreign policy decisions will resonate with historical practices and a state’s sense of identity. On the other side of the two-level game, foreign policy decision-makers face an uncertain external environment that may threaten the state’s interests. Moreover, the stakes of foreign policy decision-making can be quite high, even existential – just ask the Melians. Finally, the deliberative aspect of foreign policy decision-making focuses on specific actors’ responses to specific circumstances.

All of this comes together to create an operational definition of foreign policy, which, as Christopher Hill argues, is “the sum of official external relations conducted by an independent actor… in international relations” (2003). To break this down, the ‘sum of external relations’ is important because it demonstrates foreign policy’s interdependent nature. It combines economic, political, and military action. It combines action over time. It combines action in one policy area or with one external actor with other policy areas and other actors. By referencing ‘independent actors’, we include states as well as actors like the EU or the UN. It is important to qualify this definition by including ‘official’ external relations since foreign policy is conducted by a number of authoritative actors within the state, including state leaders, ministers, ambassadors, senior bureaucrats – essentially any actor making authoritative decisions on behalf of a recognized independent actor. Finally, we include the concept of international relations, or in our class, global politics, to situate foreign policy decision-making in the anarchical system.

Figure 7-6: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/map-of-the-world-world-parts-1340069/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of yas640.

Finally, it is useful to conclude with a list of what foreign policy tools decision-makers have at their disposal: diplomacy, economic statecraft, military force. First, and most consistently, an actor can use diplomacy to achieve foreign policy goals. This involves using a professional diplomatic service, up to and including ambassadors and state leaders, who build networks of communication to pursue their interests with other actors. It includes representation in and active use of international organizations and other fora of diplomatic activity. It also encompasses the communication of the state leadership to signal intentions and warnings to foreign actors. Diplomacy can be unilateral, bilateral, and multilateral. Unilateral diplomacy means the state is acting alone. For example, when the United States declared either you were with them or against them following 9/11, President Bush was unilaterally declaring American foreign policy intentions. Bilateral diplomacy occurs between two states. For example, when Canada and the United States issue joint declarations on a particular issue – such as the rebuke of China’s detention of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor in retaliation for Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou’s arrest. Multilateral diplomacy includes any agreements between more than two actors. Still, it most often refers to very broad diplomatic efforts, like the Paris Climate Agreement, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, or the creation of the International Criminal Court. The purpose of diplomatic activity is to pursue a state’s interest through building alliances, communicating intentions, and declaring redlines.

Figure 7-7: Heads of Delegation at the Paris Climate Summit 2015 Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:COP21_participants_-_30_Nov_2015_(23430273715).jpg#/media/File:COP21_participants_-_30_Nov_2015_(23430273715).jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Presidencia de la República Mexicana.

Second, actors can use economic statecraft. Economic tools use a carrot and stick approach to foreign policy. States can use the carrot to incentivize other actors to conform or support their foreign policy goals. The carrot can come in the form of foreign aid, trade agreements, and policies on the flow of international capital. States often use economic carrots in regions and countries that they have a vested interest in supporting. For example, the Harper government fundamentally reorientated foreign aid policy towards countries with strong economic ties to Canada and Canadian companies, most notably in the resource extraction sector in Latin America. Importantly, carrots also turn into sticks. If an actor or a country is a recipient of foreign aid, trade agreements, or beneficial capital flows, threats to reduce or remove those carrots can compel compliance or bring actors back into line.

Figure 7-8: Source: https://flic.kr/p/dWqcmR Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of michael_swan.

Third, actors can use military force. The use of military force is the most dramatic tool of statecraft. The military is the last defence of a state’s territorial integrity. For example, Ukraine has used its military forces to pushback against Russian aggression, most notably in Eastern Ukraine and the Donbas region. On the flip side of the Russo-Ukraine conflict, Russia has used its military to punish Ukraine’s pro-EU policies, annex Crimea, and reassert its regional influence. States may also use military force for more limited foreign policy goals. For example, an alliance of western states used limited airstrikes against suspected Syrian chemical weapons facilities in 2018 to punish the Syrian state’s use of chemical weapons in its civil war. A state may use the buildup of military forces as a deterrent to other states, much like the Cold War rivalry between the US and the USSR. A state may use its military power to extend an umbrella over other states in return for cooperation or simply to extend its military reach. For example, the US has extended its nuclear and conventional military umbrella over Asia Pacific states like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Finally, a state can use its military forces through multilateral policies like UN-sanctioned peacekeeping and military missions. For example, in 2021, there are 12 UN peacekeeping missions in Africa, the Balkan peninsula, the Middle East, and between India and Pakistan.

Figure 7-9: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Russo-ukrainian_war_2014-2020.jpg#/media/File:Russo-ukrainian_war_2014-2020.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Misamir-IV.

The study of global politics is primarily concerned with big picture questions. Is the anarchical system conflictual or cooperative? What role do international institutions play? When is war justified? However, when it comes to the study of foreign policy, we move towards more specific questions about specific countries in specific circumstances. Why did Canada choose to take a leadership role in promoting the human security agenda, most notably the Responsibility to Protect? Why did Russia annex Crimea? Why did the United States pull out of the Paris Climate Agreement under President Trump and join again under President Biden? To answer these questions, we move to a sub-field of global politics, Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA). FPA sits between country-specific studies and systemic studies. It asks why specific states have made specific foreign policy choices in specific contexts while also recognizing the anarchical system’s systemic constraints. FPA then tries to generalize these findings across time and actors. In other words, FPA seeks to explain why particular decisions, processes, or outcomes occur but do so in the context of the practice and study of global politics.

To accomplish these goals, FPA focuses on human agency, or, in other words, decision-makers and decision-making. Who makes foreign policy decisions, and by what authority? What limitations or constraints, both domestic and external, do decision-makers face? What are the consequences, both intended and unintended, of these decisions? To what degree have decision-makers learned from previous decisions and the policy choices made by others? To begin answering these questions, FPA considers the particular histories and political discourse of the country in question. It situates these within regional and systemic histories and structures. FPA then parses foreign policy decisions through different analytical lenses. For example, can the decision, process, or outcome in question be best understood through the structure vs agency debate? Structural constraints range from social institutions like international law to material differences like economic, political, or military resources. Agency speaks to the ability of actors to influence or change structures. For example, a group of like-minded states, including Canada, worked with NGOs to challenge traditional UN disarmament processes that had failed to ban anti-personnel landmines. The result was the Ottawa Treaty and the 1997 Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production, and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction.

Figure 7-10: Source: https://flic.kr/p/6bSu9b Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of mary wareham.

Other FPA analysts may look to the role that ideas, or normative structures, shape policymaking and implementation. For example, to what degree does the EU rhetoric of being a normative power shape their policy responses? To unpack this a bit, the EU argues it is a defender of human rights, which plays a core role in its foreign policy. When negotiating and implementing trade agreements or providing foreign aid in the majority world, the EU often includes good governance or democracy provisions. Yet, when faced with a mass influx of refugees in 2015 from the Syrian conflict, these human rights provisions were largely absent as the EU focused on border control and immigration/refugee policy.

Figure 7-11: Source: https://flic.kr/p/2kBdsrk Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Jim Forest.

Other FPA research may look to the degree that domestic bargaining between interest groups and the state influences foreign policies’ form and function. For example, when Tony Blair and New Labour formed government in the UK in 1997, one of their campaign promises was to institute an ‘ethical’ foreign policy. However, this was easier said than done. The UK is a major arms dealer, which requires dealing with unsavoury characters. For example, Blair’s Government approved a major deal with the Libyan Government of Colonel Gaddafi in 2007, weapons which Libya used against UK and NATO forces in the UN-sanctioned intervention in the Libyan Civil War in 2011. The UK is also a major financial hub, which again necessitates doing business with unsavoury characters, as does the London property market. When Blair became PM, the idea of an ‘ethical’ foreign policy soon became nothing more than rhetoric as it directly challenged important domestic interest groups.

Figure 7-12: Source: https://flic.kr/p/ak7qUi Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Jim Forest.

Some FPA applies a level of analysis approach, looking for the best means to identify the causal mechanisms that explain foreign policy decisions, processes, or outcomes. Systemic level explanations look to the condition of anarchy, the distribution of resources between actors, and the degree of political/economic interdependence. For example, the systemic level of analysis provides a good explanation of the tension in climate change policy. While there is a broad consensus that climate change is real and driven by human action, states face significant obstacles in reaching climate policy agreements. This is because there is a fear that non-signatory states will take advantage of climate change policies or that signatories will defect from their obligations. Conversely, the interdependencies of the global economy make some foreign policy choices more costly. For example, the global flow of capital tends to chase profit. This means that states who impose higher regulations or restrictions at the border may lose large amounts of capital investments. Therefore, while the state is technically sovereign, the exercise of that sovereignty may come with high costs.

A state-level of analysis suggests that government type, bureaucratic structure, domestic interest groups, and identity all can influence foreign policy decision-making. For example, when the UK was updating its nuclear program, many state variables came into play to explain what is arguably a sub-optimal outcome. The UK didn’t need to remain a nuclear power, but it resonated with its great power image. When updating its nuclear program, the government could have opted for a land-based, air-based, or sea-based system. While all three systems have strategic strengths and weaknesses, the government chose the sea-based Trident system because of its strong naval identity and economic interest groups in shipbuilding.

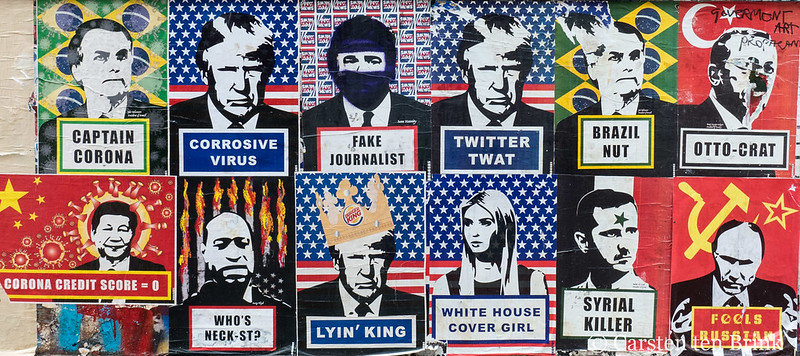

An individual-level approach looks to the influence of key actors, including decision-makers and norm entrepreneurs. This approach interrogates how individual perception, beliefs, and priorities influence foreign policy decision-making, processes, and outcomes. For example, to what degree do leaders like Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, or Rodrigo Duterte influence their states’ respective foreign policies’ form and function? While it is always dangerous to pose counter-factual questions, implicit in the individual-level analysis is whether their states’ respective foreign policies would be different had a different person been in charge?

Figure 7-14: Source: https://flic.kr/p/2kdjmoZ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Carsten ten Brink.

Graham Allison’s analysis of the Cuban Missile Crisis is a watershed moment in FPA that continues to resonate today. In 1962, the US and the USSR confronted each other over the installation of Soviet nuclear rockets in Cuba. This crisis made nuclear war between the US and the USSR a frightening possibility. For those studying foreign policy, the question was how could that crisis have happened? The concept of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) was well known. Neither the American nor Soviet leadership wanted a nuclear conflict. They didn’t believe anyone could ‘win’ a nuclear conflict. The Cuban Missile Crisis was troubling for foreign policy analysts since a ‘rational’ approach to foreign policy decision-making has great difficulty explaining how it came to be. How could nuclear war be rational?

Allison tackled this problem by proposing three foreign policy decision-making models and then compared them in terms of their explanatory value. Model I is the traditional approach, the Rational Actor Model (RAM). The RAM suggests that policymaking is an idealized four-step process whereby a unitary actor:

- Clearly identifies the problem

- Defines policy goals/outcomes

- Evaluates consequences

- Makes a rational policy choice

This is the ideal of any policymaking, domestic or foreign. We expect decision-makers to have all the information, to know what goals they are pursuing, and to pick the best policy to achieve these goals. But this is not the reality for the vast majority of domestic and foreign policy decisions. Decisions may reflect past policy orientations. Decision-makers may have incomplete information. They may have inadequate time to make decisions. The decision-maker may not be ‘unitary’ in that many voices may struggle to influence the policy decision, and those voices may not all share the same interests.

Model II is the organizational behaviour model. It suggests that organizations and decision-makers do not have the time nor the resources to study every decision as a standalone event. There is rarely time to collect all the information, or that information may not be available. As individuals and organizations, we rarely have time to reflect on our goals and order them in a rational way amongst other competing goals. Instead, most policymaking is deeply influenced by tradition and standard operating procedures (SOP). Government bureaucracies are asked for policy advice, and they turn to past decisions or the tried-and-true responses.

Model III is the governmental politics model, also known as the bureaucratic politics model. It unpacks the idea of a unitary state in policymaking and suggests that decision-making reflects a tension between independent and competing bureaucracies along with decision-makers themselves. Each of these actors pursues their policy agenda based on their parochial interests – or ‘where you stand (meaning policy stance) depends on where you sit (meaning your organizational position).’ For example, if you work in the defence department, you will likely advocate for a military response. This is not only because you believe it to be the most effective response but also because it justifies your job, budget, and department’s policy influence. Conversely, if you are in the foreign service, you will likely advocate for a diplomatic response for the same reasons. The political leadership also brings its interests, ideologies, and agenda to the decision-making processes. Cumulatively, these interests inform policy choices and implementation.

The principal contribution of Allion’s work is that the RAM is deeply flawed and does not reflect actual policymaking, or at least not most of the time. Subsequent research has shown that if the situation is novel enough, the decision-maker is interested enough, and a policy window is open, RAM may play a larger role. It also unpacks some of the actual processes at work in foreign policymaking. Allison unpacks the state, examines the bureaucracies, the role of SOPs, and the politics at work in decision-making. Further, Allison demonstrated how two nuclear-armed states might stumble into war, even if no rational actor would desire that. This carries important lessons for global politics today, as we face an increasing number of actors with WMDs or the potential to access them. Ultimately, Allison’s work suggests that we need to understand how foreign policymaking actually happens and that a failure to do so may have existential consequences.

Figure 7-15: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1962_Cuba_Missiles_(30848755396).jpg#/media/File:1962_Cuba_Missiles_(30848755396).jpgPermission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Central Intelligence Agency.

Unlike the big picture questions of global politics, foreign policy analysis looks at specific foreign policy decisions, albeit embedded in the big picture. The focus is on foreign policy decisions, processes, and outcomes. FPA takes a variety of roots to parse these decisions, processes, and outcomes. Some analysts use the structure/agency debate. Some analysts assess the importance of ideational/normative structures or competing domestic interests in shaping policy decision-making. Still, others apply the level of analysis approach to explain foreign policy decisions, processes, and outcomes. Finally, it is useful to look at Graham Allison’s work on the Cuban Missile Crisis to unpack the three models of foreign policy decision-making and to highlight the potential costs of not doing so – perhaps even existential costs.

It is useful to examine foreign policy decision-making through our theories and approaches to global politics. While Foreign Policy Analysis focuses on decision-making and decision-makers, these are not country studies nor diplomatic history. Instead, FPA seeks to explain specific decisions, processes, and outcomes but contextualized in global politics. This analysis intends to compare cases and seeks to generalize findings. In terms of foreign policy, we can start to see the differences in the variants of Realism. All the variants share a world view that privileges the state, self-help, and a central focus on power. Moreover, all the variants privilege the system level of analysis while recognizing to varying degrees the state and individual levels. In general, Realism resonates with the FPA’s focus on actual foreign policy decisions and decision-making versus idealistic prescriptions of what ‘should be’. However, beyond that, there are some important differences. Structural Realism has the least overlap with foreign policy. Since Structural Realists argue that the distribution of capabilities dictates state behaviour, there is little room for state leaders’ agency and, therefore, little interest in the study of foreign policy. At best, there is an expectation that decision-makers will correctly assess their state’s place in the hierarchy of power and act accordingly. Classical Realism has a better appreciation of foreign policy in that it emerged out of the practices of the Concert of Europe, and more specifically, the diplomatic practices of the late 19th century. They applaud diplomats who can artfully advance the interests of their state on the world stage. However, it is partly the preoccupation of diplomatic history that led to Structural Realism’s development as a more scientific approach to global politics.

This brings us to Neo-Classical Realism (NCR), which in many ways was motivated by the failure of Structural Realism to account for specific foreign policy decisions/outcomes like the end of the Cold War. NCR combines the logics of Classical and Structural Realism. It acknowledges the defining role that the distribution of resources in an anarchical system plays in enabling or constraining foreign policy decisions. However, it also recognizes the agency that individual decision-makers have in navigating that terrain. More specifically, NCR has developed a body of literature that explains how domestic-level variables explain the frequent disconnect between systemic prompts and actual foreign policy decisions. These include decision-makers’ perception/misperception of systemic prompts and other state’s intentions, the impact of the state’s institutional arrangements, and the relative powers of elites and interest groups. NCR is very much a theory of foreign policy, albeit one limited to the assumptions of the Realist canon.

Figure 7-16: Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:GCCMAP_2019.png#/media/File:GCCMAP_2019.png Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of DOD Updater Private.

In contrast, Liberalism privileges the state and individual level of analysis in Foreign Policy Analysis while recognizing the constraints posed by the anarchical system. In terms of FPA, Liberals recognize the privileged role of the state in global politics, but also the role of institutions, MNCs, NGOs, and norm entrepreneurs. The goal of a Liberal foreign policy is to expand the community of liberal democratic states, increase economic interdependence, and build increasingly dense networks between states, institutions, NGOs, and MNCs. In so doing, Liberalism argues it is possible to approach Kant’s ideal of perpetual peace, built upon norms of individual liberty, prosperity, and mutually derived security. However, with that being said, a Liberal foreign policy faces significant obstacles in practice. First, a Liberal foreign policy has great difficulty in deciding how to promote human rights in non-Liberal parts of the world. Liberalism as a political philosophy has deep ambivalence with how the state can and has been a threat to individual liberty. However, what is to be done when human rights are violated in non-liberal parts of the world? Liberal democratic states can stand as the ‘city on the hill’, providing an example for others to follow – but that does little for those facing imminent harm by their own state. Direct intervention requires the use of state force, but that not only means intervening in the domestic affairs of another state, but it also requires a robust military in one’s own state which could be a threat to the citizenry. On top of this, even if an intervention is militarily successful, there is little evidence that liberal democracies know how to engage in successful state-building post-conflict. Second, while democratic peace theory supports the value of expanding the circle of liberal democratic states, it does not suggest that liberal democratic states are more peaceful. In fact, liberal democracies have demonstrated significant aggression towards non-democracies. The US is a perfect example of this, having been at peace for roughly 20 years in its 243-year existence.

Figure 7-17: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RIAN_archive_828797_Mikhail_Gorbachev_addressing_UN_General_Assembly_session.jpg#/media/File:RIAN_archive_828797_Mikhail_Gorbachev_addressing_UN_General_Assembly_session.jpgPermission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of RIA Novosti.

Much like in our other modules, Constructivism does not provide specific prescriptions regarding foreign policy. Instead, Constructivism is interested in the processes of social construction at work in foreign policy. In terms of Foreign Policy Analysis, Constructivism examines the processes that shift identities, interests, and practices. There are three key areas of Constructivist interest in FPA. First, how are identities, interests, and roles constructed within particular foreign policy communities? For example, what are the expected roles and influence of the actors, agencies, and bureaucracies that constitute the American foreign policy community versus Canada? How and why have these roles and influences changed over time? Second, what are the processes of foreign policy decision-making in particular states? How do they change over time? How do they differ from other states? Why? Third, to what degree do international norms and institutions shape the process of foreign policy decision-making and the conduct of foreign policy between states. In the end, a Constructivist take on FPA centers on changes to foreign policy communities, foreign policy processes, and how these shape identities, interests, and practices.

Figure 7-18: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/binary-one-null-continents-earth-1414317/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Critical and Post-Structural approaches both view foreign policy as another instrument that entrenches the privilege of the powerful within and across states. For example, for the most part, FPA takes for granted the concept of the ‘national interest’. This seems non-controversial since decision-makers have to know what they are trying to achieve in order to make a foreign policy decision. However, the idea that a singular national interest can be defined is highly problematic. Take Canada, for example: who is defining the national interest? Based on what criteria? To whose benefit and whose detriment? Are the interests espoused by Ottawa the same as those in Vancouver, Calgary, Saskatoon, or St Johns? How about between the manufacturing and resources extraction industries? How about between Indigenous and non-indigenous peoples? From our critical approaches to global politics, Marxist, Feminist, and Environmentalist views of the national interest would be quite distinct from the government of the day. In general, Critical approaches would question who the ‘national interest’ benefits and how understanding that allows for a more equitable discussion on foreign policy goals.

Similarly, Post-Structural approaches to foreign policy would deconstruct the discursive practices that privilege foreign policy, foreign policy communities, and the state itself in global politics. From a Post-Structural perspective, FPA normalizes discourses that should be contested. The idea that the state is a privileged and central actor in global politics undermines alternative discourses of political organization. Foreign policy legitimates the privileged discourse that the state is acting to further the national interest. Moreover, the artificial division of domestic and foreign policy obscures alternative discourses that recognize shared interests across borders that may supersede national affiliation. These privileged discourses in FPA internalize discourses that entrench and maintain the privilege of the powerful. For example, the invocation of R2P and other supposedly humanitarian foreign policies rarely result in the intended outcomes. In R2P missions, civilians are rarely made safer, post-conflict states are unlikely to be more stable, and the underlying causes of insecurity are seldom addressed. However, the narrow interests of the powerful states who invoked R2P are often met. For example, in the 2011 Libyan intervention, UN-sanctioned NATO troops left a political, military, and humanitarian mess. Yet, the operation did meet some of the NATO members’ interests who wanted to expand their influence in North Africa, militarize the Mediterranean, and demonstrate their military prowess.

Figure 7-19: Source: https://flic.kr/p/26HxwTo Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of UNMISS.

We have defined foreign policy as the sum of official external relations conducted by an independent actor in global politics. This definition includes state and non-state actors like the UN. It focuses on discrete decision-making but also recognizes the interdependent nature of foreign policy over time, across issues, and between multiple actors. It recognizes the range of policy tools at decision-makers’ disposal, including diplomacy, economic statecraft, and military force. It limits the study of foreign policy to official external relations, narrowing the scope of FPA. However, this is still a broad field of inquiry that seeks to explain a wide range of actions. It is important to recognize that the entry point of all FPA is what is done and why – in other words, FPA focuses on decision-makers and decision-making. FPA analysts draw on the two-level nature of foreign policy decision-making, the influence of normative structures, the tension between structure and agency, the level of analysis approach, and domestic variables’ importance. We used Graham Allison’s work on the Cuban Missile Crisis to unpack three models of foreign policy decision-making, including the Rational Actor Model, the Organizational Behaviour Model, and the Government Politics Model. More importantly, Allison’s work demonstrates the importance of taking FPA seriously since the possibility of getting it wrong could have existential consequences.

Review Questions and Answers

To paraphrase Christopher Hill, foreign policy is the sum of official external relations conducted by an independent actor in global politics. Each term of this definition provides insight into foreign policy and foreign policy decision-making. The ‘sum of external relations’ is important because it demonstrates foreign policy’s interdependent nature. It combines economic, political, and military action. It combines action over time. It combines action in one policy area or with one external actor with other policy areas and other actors. By referencing ‘independent actors’, we include states and actors like the EU or the UN. It is important to qualify this definition by including ‘official’ external relations since foreign policy is conducted by a number of authoritative actors within the state, including state leaders, ministers, ambassadors, senior bureaucrats – essentially any actor making decisions on behalf of a recognized independent actor. Finally, we include the concept of international relations, or in our class, global politics, to situate foreign policy decision-making in the anarchical system.

Critical and Post-Structural approaches both view foreign policy as another instrument that entrenches the privilege of the powerful within and across states. For example, for the most part, FPA takes for granted the concept of the ‘national interest’. This seems non-controversial since decision-makers have to know what they are trying to achieve in order to make a foreign policy decision. However, the idea that a singular national interest can be defined is highly problematic. Take Canada, for example: who is defining the national interest? Based on what criteria? To whose benefit and whose detriment? Are the interests espoused by Ottawa the same as those in Vancouver, Calgary, Saskatoon, or St Johns? How about between the manufacturing and resources extraction industries? How about between Indigenous and non-indigenous peoples? From our critical approaches to global politics, Marxist, Feminist, and Environmentalist views of the national interest would be quite distinct from the government of the day. In general, Critical approaches would question who the ‘national interest’ benefits and how understanding that allows for a more equitable discussion on foreign policy goals. Post-Structuralism deconstructs the discursive practices of ‘national interest’ and the ways it reinforces the privileged position of the state. A singular national interest suggests that a sharp division between the inside and outside of political organization. It suggests the outside is dangerous and that people need a strong state apparatus to protect them. Moreover, the artificial division of domestic and foreign policy obscures alternative discourses that recognize shared interests across borders that may supersede national affiliation. These privileged discourses in FPA internalize discourses that entrench and maintain the privilege of the powerful.

Glossary

Diplomacy: involves using a professional diplomatic service, up to and including ambassadors and state leaders, who build networks of communication to pursue their interests with other actors

Economic Statecraft: uses a carrot and stick approach to foreign policy; carrots incentivize other actors to conform or support foreign policy goals through foreign aid, trade agreements, and policies on the flow of international capital. Carrots can turn to sticks if a state removes them or threatens to remove them.

Foreign Policy Analysis: sits between country-specific studies and systemic studies. It asks why specific states have made specific foreign policy choices in specific contexts while also recognizing the anarchical system’s systemic constraints

Foreign Policy: the sum of official external relations conducted by an independent actor in global politics

Governmental Politics Model: unpacks the idea of a unitary state in policymaking and suggests that decision-making reflects a tension between independent and competing bureaucracies along with decision-makers themselves

High Politics: refers to those issues that are of paramount importance to the state, usually associated with security issues and formal diplomacy

Military Force: is the most dramatic tool of statecraft. It is the last defence of a state’s territorial integrity, a stick for limited military strikes, and through mobilization, a deterrent to other states.

National Interest: the goals of the state as perceived and defined by the government

Organizational Behaviour Model: suggests that policymaking is deeply influenced by tradition and standard operating procedures

Rational Actor Model: suggests that policymaking is an idealized four-step process whereby a unitary actor: clearly identifies the problem, defines policy goals/outcomes, evaluates consequences, makes a rational policy choice

References

Clark, Campbell. “Foreign Aid as a Tool for Canadian Development.” The Globe and Mail, August 15, 2013.

Ingelevič-Citak, Milena. “Crimean Conflict – from the Perspectives of Russia, Ukraine, and Public International Law.” International and Comparative Law Review 15, no. 2 (2015): 23-45.

Nas, Tevfik F. Tracing the Economic Transformation of Turkey from the 1920s to EU Accession. Leiden ; Boston: Martinus Nijhoff, 2008.

Hill, Christopher. The Changing Politics of Foreign Policy. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, [UK]: Palgrave MacMillan, 2003.

Axworthy, Lloyd. “The Ottawa Treaty.” Canada’s History 92, no. 1 (2012): 73.

De Genova, Nicholas, and Duke University Press Issuing Body. The Borders of “Europe”: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of Bordering. E-Duke Books Scholarly Collection. 2017.

“Syria Air Strikes: US and Allies Attack’ Chemical Weapons Sites’.” BBC News. BBC, April 14, 2018.

“UK Remains Second Biggest Arms Exporter with £11bn of Orders.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, October 6, 2020.

Ritchie, Nick. Trident and British Identity: letting go of nuclear weapons. Department of Peace Studies, University of Bradford. 2008.

Jack, Ian. “Trident: the British Question.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, February 11, 2016.

Holloway, Steven Kendall. Canadian Foreign Policy: Defining the National Interest. Peterborough, Ont. ; Orchard Park, NY: Broadview, 2006.

Hill, Christopher, and Oxford Scholarship Online. The National Interest in Question Foreign Policy in Multicultural Societies. 2013.

Ripsman, Norrin M., Taliaferro, Jeffrey W., Author, Lobell, Steven E., Author, and Oxford Scholarship Online. Neoclassical Realist Theory of International Politics. 2016.

Jahn, Beate. Liberal Internationalism : Theory, History, Practice. Palgrave Studies in International Relations. 2013.

Hynek, Nik. Human Security as Statecraft : Structural Conditions, Articulations and Unintended Consequences. Routledge Critical Security Studies Series. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York: Routledge, 2012.

Supplementary Resources

- Hill, Christopher. The Changing Politics of Foreign Policy. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, [UK]: Palgrave MacMillan, 2003.

- Hudson, Valerie M. Foreign Policy Analysis: Classic and Contemporary Theory. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007.

- Jørgensen, Knud Erik, and Hellmann, Gunther, Editor. Theorizing Foreign Policy in a Globalized World. Palgrave Studies in International Relations. 2015.