"The House of Commons sits in the West Block in Ottawa" Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0. Courtesy of Leafsfan67.

Module 1: Introduction to Comparative Public Policy

Public policy matters. This is in a very large part because policy involves social processes that are intertwined with our everyday lives, often in very profound ways. Your access to basic necessities such as food, water, clean air and healthcare is decided by public policies. The quality of our schools, restrictions on access to abortion, and the conditions of our highways are all governed by government policies. Even your tuition and the programs of study available are deeply influenced by public policy. How these decisions are made, who gets to influence the decision making, how these policies are implemented, and how policies are evaluated once implemented, all make up the study of public policy. This policy-making process, whether undertaken in the Parliament of Canada in Ottawa, the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan in Regina, City Hall in Saskatoon, or by the Board of Governors at the University of Saskatchewan, is of direct relevance to your life. Read more...

"EP seeks equal treatment for self-employed by European Parliament" Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (https://www.flickr.com/photos/european_parliament/4618393525) Courtesy of European Parliament.

Module 2: Theories of Policy Making

It might appear that public policy making has a national or even provincial/state and municipal focus. Moreover, it would seem many assume this to be sufficient. So, why should researchers and policymakers be interested in investigating the policy-making systems and processes in other nations, provinces/states, and municipalities? As discussed in the previous module, the stakeholders involved in designing and delivering public policy, as well as assessing policy outputs and outcomes, vary significantly across nations. National, regional and local governments adopt a large variety of approaches towards similar policy problems. Even amongst relatively similar countries with apparently identical aims, we find radically divergent policy approaches. Just think about health care policy in Canada and the US. Both countries are seeking to design and implement policies which will increase the health of their citizens. However, the US has adopted a system of privatized health care provision supported by private insurance providers, and Canada has adopted a single-payer system. Both are seeking to achieve many of the same goals, and yet they have adopted diametrically opposed health care policies. Further, even similar policies can produce impacts that vary significantly depending on the social, cultural and national context in which they are implemented. Take gun control policies in Canada and the US for example. In the US, attempts to impose limitations on the type and quantity of firearms that a citizen may own is portrayed as the work of an authoritarian state that seeks to undermine a citizen’s constitutional right to defend themselves. In Canada, on the other hand, gun ownership is not a right but rather a privilege, and this leaves much more room for significant gun control legislation. In both cases, proponents are seeking to impose limitations on gun ownership, but the respective social, cultural, and national contexts generate significantly different reactions to these policy initiatives. Read more...

Ideas. Image by TeroVesalainen from Pixabay

Module 3: Ideas and Public Policy

In the first two modules, we set the context of this course. In Module 1, we defined the field of public policy, the function and role of comparative studies, and the broad scope of the policy cycle. In Module 2, we introduced a range of theoretical approaches to Comparative Public Policy, including John Stuart Mill’s method of agreement and method of difference, the cultural school, the economic school, the political school, and the institutional school. Together, these two modules set the broad boundaries of what we are investigating in this course. In the next three modules, we will be looking in depth at three elements which are important mutually constitutive elements of the policy environment: 1. Institutions: both formal organizations and the informal patterns of rules, norms, and practices that shape the behaviour of actors; 2. Interests: a wide range of forces which create contextual frames that motivate both individuals and organizations to be deliberate and act in particular ways; 3. Ideas: both conscious and sub-conscious frames which shape beliefs and subsequently constrain or facilitate the progress of new ideas as policy solutions. Read more...

Interests. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/fingerprinting-blaming-division-2223862/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of johnhain.

Module 4: Interests and Public Policy

Interests are the most operationalized variable in public policy analysis since this is what often motivates actors to seek change or to defend the status quo. It is interesting to contrast this with the role of ideas in Module 3. Cognitive paradigms, normative ideas, or world culture may shape what an actor believes to be true, right, and/or appropriate. But that alone may not be enough to motivate an actor to try and influence public policy. Interests on the other hand, if threatened and if important enough, often will motivate action: lobby decision-makers, join political parties, march in rallies, donate to causes, start new social movements, et cetera. Think of the example given in Module 3 on the Alabama legislation which makes abortions illegal and can punish those who perform abortions with 99 years in jail. Most people have ‘ideas’ on abortion. Those who are adamantly pro-life or pro-choice will often be advocating on behalf of these ideas that they believe to be true, right, and/or appropriate; think of all the social media posts you might have seen. But until people’s interests are at stake, those actively and consistently involved in advocacy, beyond a Facebook post, tend to be a relatively small minority. Once the Alabama law takes effect, many more people will have an interest in supporting or opposing the law, both in and beyond Alabama. Doctors and other health care workers will have an interest in the debate. Women’s reproductive rights activists will have an interest in the debate. Women more generally will have an in interest in who can and cannot legislate on their reproductive rights. Those with a strong moral stance on either side will have an interest in the debate. This demonstrates that while ‘ideas’ matter, they may require some trigger to motivate action. And this trigger is often a perceived opportunity for or threat to one’s interests. Read more...

Institution. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/143106192@N03/42842884544/ Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Mike Cohen.

Module 5: Institutions and Public Policy

In Module 3, we introduced the concept of ideas, how ideas play a role in public policy and the case of Canadian Middle Power internationalism as evidence of an ideational influence in public policymaking. In Module 4, we introduced the concept of interests, how interests play a role in public policy, and the case of Canadian environmental interest groups as evidence of the role interests play in public policymaking. In this module, we will be turning to the last of the three concepts, institutions. We have already seen traces of institutional impact in our previous two modules. We glimpsed the role of institutions in Module 3 when we examined the role of programmatic ideas in responding to the 2008 financial crisis. The responses by governments around the world were largely similar, based on shared ideas of the best response. But these ideas were formed and implemented through institutions. In Module 4, we discussed the interaction between interest groups and the government. While interests largely defined this interaction, institutions played a role in structuring it. Therefore, in this module, we will be turning to the concept of institutions. Institutions are discernible in almost everything we do individually and collectively. Institutions most generally can be seen as structures that shape what we do, how we do it, and some argue even why we do it. They create and sustain norms, rules, and procedures that both formally and informally constrain and enable particular behaviour. Read more...

Conservative leader Andrew Scheer speaks to media. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/andrewscheer/26303073368/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Andrew Scheer.

Module 6: Politics and Public Policy

The approach taken so far is, in many ways, a bit misleading. For example, it may seem that public policy is a relatively linear process: problems are identified and put on the agenda by decision-makers, bureaucracies and epistemic communities suggest solutions, decision-makers debate the options, identify the best solution, and implement it. This linear conception is very clean and precise. It is very rational. It meets most people’s standard of the ‘right way’ to solve policy issues. In practice, public policy is rarely so neat. Rather, it is often the case that policy issues, policy solutions, and the political context are operating independently of one another or even at cross purposes. A new policy may start as a ‘pre-packaged’ solution looking for a problem to solve. It may start as a shift in the political context, where decision-makers are looking to make their mark on the policy agenda. It may start as a sudden threat or opportunity that decision-makers face, but one in which the lack of feasible options stymies a 'solution.' Each of these examples run counter to the neat image we often have of the linear policy process. Instead, it suggests that public policy is a complex process. Moreover, it may seem that all policy issues are simply waiting for ‘their turn.’ That policy-makers will eventually address all policy issues. They will do so rationally, finding the optimal solution, and without bias. However, this is one of the biggest misconceptions of public policy. Many policy issues, while deeply significant to some people, have difficulty making it on to the institutional agenda of decision-makers. Such issues may linger in narrow segments of the systemic agenda for an indeterminant period, and ‘their time’ may never arrive regardless of how important they may be for specific sub-sections of the polity. Policymakers have to balance a wide variety of demands made by their constituents, by the civil servants acting on their behalf, by their political party, and even by their preconceived ideas of what is appropriate. In the end, policymakers have to make decisions on where to spend the resources at there disposal, by choosing how much, if anything, to commit to these demands.

Both policy complexity and the selection of policy issues point to an important factor that we have alluded to but not directly engaged with: politics. Therefore, in this module, we will turn to the concept and role of politics in the public policy process. Specifically, we will introduce multiple stream approach (MSA) to public policy, More specifically, we will introduce the concept of a ‘policy window’ as defining that moment when an issue, a solution, and political will align to address a policy issue. Read more...

Global dimensions. Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

Module 7: Global Dimensions of Comparative Public Policy

In this module, we are going to examine how the processes of globalization have influenced comparative public policy analysis. Globalization is a contested term. The debate over what defines and constitutes globalization is about whether the economic, political, and social processes of globalization are something new and transformative in nature, or whether they are simply a continuation of processes that stretch back hundreds if not thousands of years. This debate is important to the study of comparative public policy analysis. If the stronger narrative of globalization as transformation is true, then national policy making will be deeply constrained and international and even supranational bodies will play a greater role. It also means that the logic of the market and competition will push policy makers in particular directions and might constrain their ability to pursue robust social welfare programming. It the weaker narrative of globalization as constituted by age old processes is true, then policymakers will adapt as they always have.

In order to understand the impact of globalization on public policy making, we will examine it through the tools of public policy so far introduced. We will then close with an examination of the two most direct consequences of globalization on public policy making, the increase in the trade of commodities and the rise of the investment capital. From this discussion, it is important to recognize that globalization has shaped and will continue to shape public policymaking. Read more...

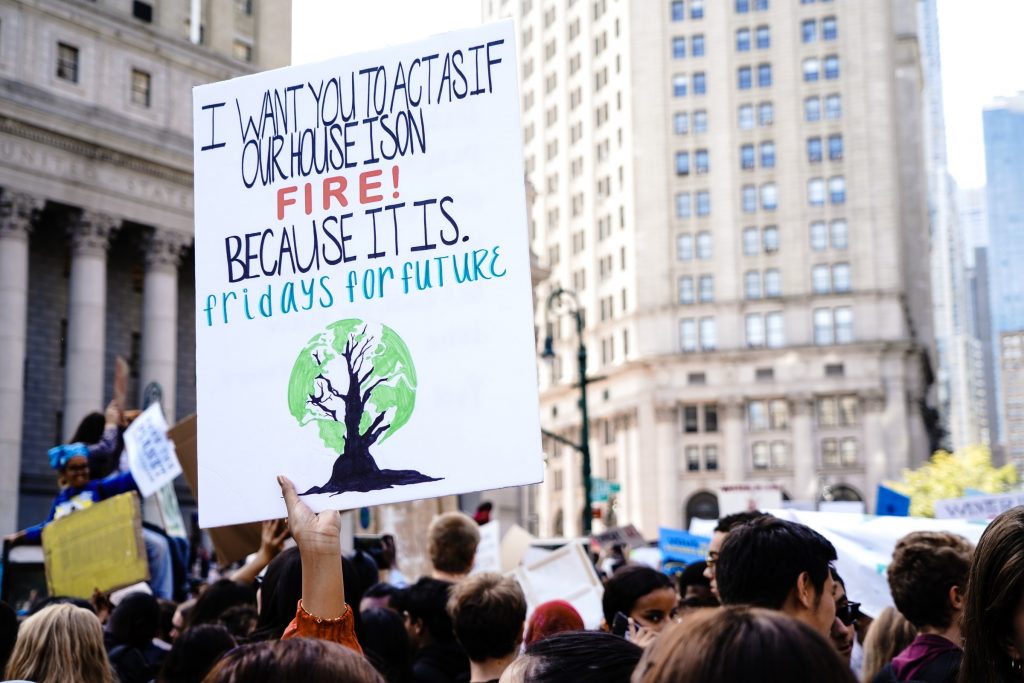

Global Climate Strikes NYC. Photo by Katie Rodriguez on Unsplash.

Module 8: Comparative Environmental Policy

In this module, we will be transitioning from a look at the global level of policy making to our first policy issue – environmental policy. This is perhaps the most appropriate policy issue to start with as it is the most ‘global’ of the policy issues will be looking at. The module will begin with an introduction to the concept of environmental governance and environmental policy. More specifically, we will look at the long history of environmental issues that can be traced back to ancient times and the move towards the contemporary environmental policy context. In the contemporary policy context, we will note the expanding circles of policy making from domestic policy, to bilateral agreements, to multilateral agreements. We will also introduce some specific theories of comparative environmental policy. After introducing environmentalism as a policy area, we will examine it through our tools of public policy analysis: the policy cycle, ideas, interests, institutions, the MSA, and critical perspectives. Finally, we close by looking at carbon emissions as an environmental policy issue and suggest some the ways it can be examined in a comparative way. Read more...

Canada declaration. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/diversey/17403633292/. Permission: CC BY 2.0

Module 9: Comparative Immigration and Citizenship Policy

In this module, we turn to another contentious policy issue, and one with an international dimension but with a distinctly more national decision-making context: immigration and citizenship. Immigration and citizenship is perhaps an even thornier issue area for decisionmakers than environmental policy as it speaks to issues of belonging, identity, rights, and obligations. The positions that people hold on immigration and citizenship can be quite intractable. Some perceive immigrants as a threat to jobs and a threat to cultural homogeneity. For others, immigrants are a necessity to balance an ageing demographic and to fill gaps in the labour market that locals are unwilling to do. And, still others, see immigration policy as a humanitarian obligation and a means to offer refuge to those at risk from persecution or struggling to survive human-made or natural disasters. Even the terminology used in debates on immigration is loaded and contentious. Those who are more pro-immigration use terms like refugee, irregular migrant and asylum seeker. Those who hold more anti-immigration views tend to use terms like illegal migrant, economic migrant, and even potential terrorists. These debates are further embedded in a global dialogue on the rights of migrants and the application of international humanitarian law. Policymakers find themselves caught in this debate between competing narratives of immigrants as a threat, as an opportunity, and as a humanitarian responsibility. Read more...

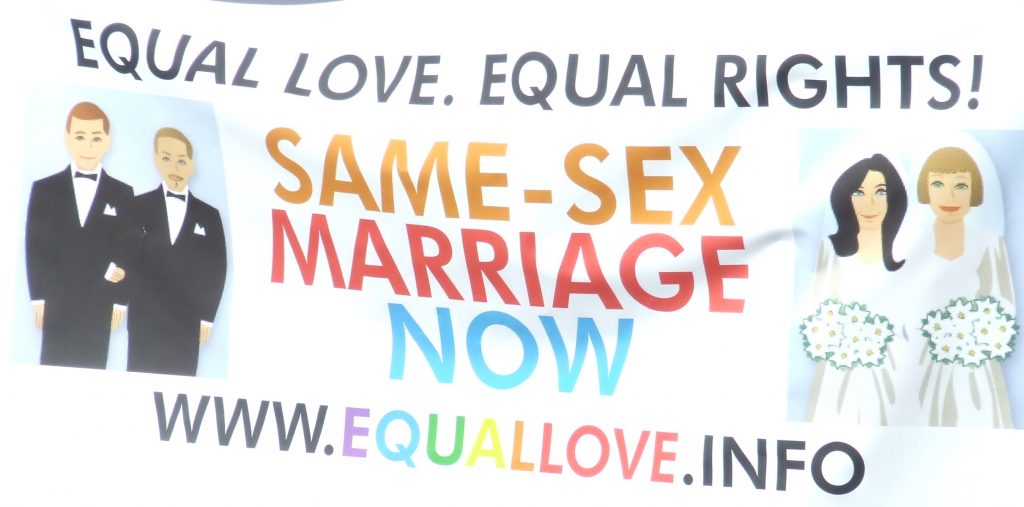

Banner from a Same Sex Marriage Rally, Brisbane, Australia. Source: https://flic.kr/p/6KTTSc. Permission: CC BY 2.0

Module 10: Comparative Public Policy and Same-Sex Marriage

In this module, we turn to another policy issue with deep divisions within society, same-sex marriage (SSM). The policy issue of same-sex marriage was, and continues to be, contentious in many places around the world. In the LGBTQ community, same-sex marriage is, for the most part, an issue of equality. The denial of marriage to same-sex couples, even when recognizing their relationship as a civil partnership, is seen by many as a form of segregation, drawing on the narrative of the civil rights movement in the US. Further, the ‘separate but equal’ status of civil partnerships lends legitimation to discrimination. In the end, recognizing that the partnership between same-sex couples is no different than any other partnership is simply an issue of fundamental human rights. For those who oppose same-sex marriage, this is an identity and cultural issue, particularly for social conservatives and fundamental Christians. The strongest objection to the recognition of same-sex marriage is the claim that it devalues the sanctity of the institution of marriage and threatens to destabilize the family structure. In the end, opposing same-sex marriage is about identity. Read more...

Health care policy. Image by mohamed Hassan from Pixabay

Module 1: Comparative Health Care Policy

This is the last substantive module in the course, and the topic of health care is probably the most relevant issue to wrap up a comparative public policy course in Canada. Healthcare is a policy that defines much of the Canadian narrative of what the country is and how it is different than the United States. While previous issues introduced in this course, including environmental policy, immigration policy, and same-sex marriage policy, are all contentious with entrenched stakeholders on more than one side, health care policy is an essential part of how Canadians understand themselves. In this module, we will define the field of healthcare as both the practice of medicine and the institutional structures that support its delivery. We will look at the constituent forms of the practice of medicine, in particular, what defines primary, secondary, and tertiary care. We will introduce the goal of health care as established by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the institutional requirements to make that a reality. Next, we will look at the different typologies of healthcare systems. These typologies differentiate between on the basis of healthcare provision, consumption, and technological research. Read more...

Course reflections. Photo by Startup Stock Photos from Pexels.

Module 12: Course Reflections

This is the final module of POLS 326 – Comparative Public Policy. So far, in this course, we have sought to accomplish three broad goals. First, we have sought to introduce and survey the field of public policy. We sought to answer some of the key questions to guide our study. What is public policy? Why is it significant? What are some examples of public policy issues? We also introduced the cycle of policymaking and the roles of those in policymaking. This added some more questions to answer. Who are the policymakers? For whom and to what purpose do they make policy? Second, we sought to introduce the tools of public policy analysis and comparative public policy analysis. Again, this added some more questions to ponder. How can we compare policy? Should we look for similar cases to compare, seeking to isolate variables of difference? Should we look for different cases that yet share similar outcomes? Should we look to or build typologies that explain policy processes or policy outcomes? What about the voices not commonly heard? What does a critical analysis of public policy look like? Third, we introduced some examples of public policies and what a comparison of them might look like, including environmental policy, immigration and citizenship policy, same-sex marriage policy, and health care policy. What we are asking you to do in this module is reflect on the course as a whole. We are asking you to reflect on the course material: public policy, comparative public policy, and the issues of comparative public policy analysis. We are asking you to reflect on what you have learned. Finally, we are asking you to reflect on both the utility of comparative public policy analysis and some areas of enquiry that you think could benefit from such analysis. Read more...