Developed by:

Dr. Martin Gaal – University of Saskatchewan

Sharmi Jaggi – University of Saskatchewan

Overview

Figure 1-1: The House of Commons, the lower chamber of the Canadian Parliament at the capital city of Ottawa Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Courtesy of S. Kaya.

Public policy matters. This is in a very large part because policy involves social processes that are intertwined with our everyday lives, often in very profound ways. Your access to basic necessities such as food, water, clean air and healthcare is decided by public policies. The quality of our schools, restrictions on access to abortion, and the conditions of our highways are all governed by government policies. Even your tuition and the programs of study available are deeply influenced by public policy. How these decisions are made, who gets to influence the decision making, how these policies are implemented, and how policies are evaluated once implemented, all make up the study of public policy. This policy-making process, whether undertaken in the Parliament of Canada in Ottawa, the Legislative Assembly of Saskatchewan in Regina, City Hall in Saskatoon, or by the Board of Governors at the University of Saskatchewan, is of direct relevance to your life.

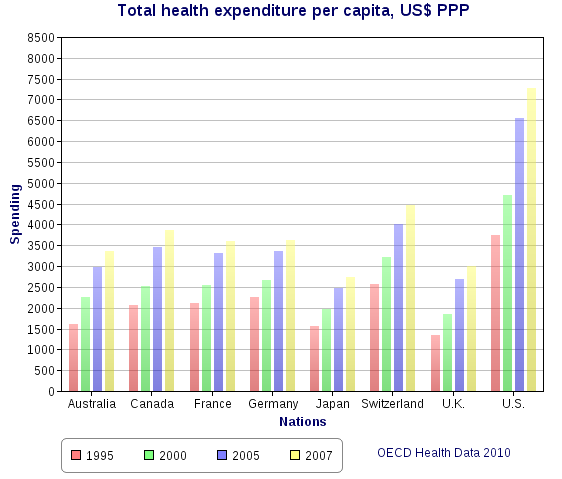

Therefore, we study public policy. We want to know why a particular decision was made. What alternatives are/were available. Why this policy choice was preferable. How this policy was implemented. Was the policy evaluated after implementation and, if so, was anything learned from that. Put in concrete terms, why did so many governments decide to ‘bailout’ the banks, rather than let them fold, after the financial crisis in 2008? Why did many governments ‘privatize’ their industries and introduce private-sector ideas to the public sector beginning in the 1980s? Why have so many governments introduced major tobacco control policies while others, such as Germany, have opposed further controls? Why did the Australian government reform gun laws in 1996 whereas the US has seen no meaningful reform despite numerous mass shootings? You might have noticed something interesting here. Not only are we looking at specific policies, but we are also looking at how different decision makers in different places choose/implement different policies to tackle the same or similar problems. Therefore, we are not only looking at studying public policy, but we are also studying it in a comparative way. How do Canada and the US draft, implement, and modify health care differently? What can they learn from each other?

Figure 1-2: Total health expenditure per capita, US Dollars PPP Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Sugar-Baby-Love.

The context in which decision makers make public policy decisions is not entirely scientific, it is to a very large degree political and economic. It can even have cultural components. As such, we recognize that there are many different answers to these questions. These answers are based on different perspectives. We can focus on individual policymakers, examining how they analyze and understand policy problems. We can consider their beliefs and how receptive they are to particular ideas and approaches to the problem. We can focus on institutions and the rules that policymakers follow. We can identify the powerful groups that influence how policies are made. We can focus on the socio-economic context and consider the pressures that governments face when making policy. Or, we can focus on all five factors. Most contemporary accounts try to explain policy decisions by focusing on one factor or by combining an understanding of these factors into a single theory. However, there is no single unifying theory in public policy. Rather, we should take the insights from one and compare it with insights from others to pursue better policy, even if the definition of 'better' can itself be contingent.

Figure 1-3: The G20 Leaders Summit Permission: CC BY 2.0.Courtesy of Presidencia de la República Mexicana.

Public policy is how politicians make a difference. Politicians are the elected decision makers with formal responsibility for complex, intricate subsystems composed of a variety of participants and players. Policy is the instrument of governance, the decisions that direct public resources in one direction but not another. It is the outcome of the competition between ideas, interests and institutions that drives our political system. This means public policy emerges from the world of politics. This can be a chaotic place in which ideas must find a path between the intentions of politicians, the interests of various government institutions, the interpretations of bureaucrats, and the intervention of pressure groups, media and citizens. All of these players have competing interests and fight to have their voices heard above the fray. Therefore, focusing on public policy encourages a focus on substance. After all, the main reason politics matters is because those who exercise political authority make decisions that have profound effects on their societies. To understand patterns in public policy is to understand a great deal about the content of politics, of what people are fighting for and why, and of why/how some are more successful than others.

Figure 1-4: Woman power logo. Permission: Public Domain.

The contemporary study of public policy has emerged in the 1970s and has been among the most rapidly developing fields in the social sciences over the past several decades. The study of public policy has emerged to provide both a better understanding of the policymaking process and to supply policy decision makers with reliable policy-relevant knowledge about pressing economic and social problems. It is important to note that despite this movement to be more systematic in the consideration and assessment of policy alternatives, our understanding of public policy processes and how government policies and actions should be explained or understood, has not really advanced very far. There is a proliferation of isolated studies, and of different methods and approaches, but precious little in the way of explanation. It should also be noted that much of the study of public policy is found within a bounded framework that makes assumptions about its goals, methods, and means. In response, we have seen the emergence of a critical approach to public policy questions that deconstruct these assumptions. Critical approaches ask new questions, particularly with a focus on gender, class, and power. Therefore, in this class, we will be examining both the mainstream processes of public policy-making as well as the critiques of these processes. And we will be doing this in a comparative fashion.

However, in this module, we want to lay out the foundations for the rest of the course. First, we will introduce students to the definition of public policy, something more elusive than one might think. Second, we will introduce the utility of adding a comparative dimension to our study of public policy: what can we learn from what others have done on addressing similar policy issues? Finally, we will end with the most common heuristic in understanding public policy-making, the policy cycle.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain why it is important to study public policy.

- Discuss why it is important to analyze similarities and differences in public policy between states in a comparative fashion.

- Use the policy cycle to understand public policy-making.

- Public policy

- Comparative public policy

- Policy cycle (5 stages)

- Agenda setting stage

- Public agenda / Systemic agenda

- Institutional agenda

- Policy formulation stage

- Decision-making stage / Policy adoption stage

- Policy implementation stage

- Policy evaluation stage

- Administrative evaluations

- Judicial evaluations

- Political evaluations

- Agenda setting stage

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

N/A for this module.

Learning Material

Introduction

In order to begin to understand and operationalize the ideas of comparative public policy, we need to agree on working definitions and introduce the analytical frameworks we will work with. In this module, we are going to introduce three key concepts that will inform much of what we will be doing going forward:

- public policy

- the ‘comparative’ element of public policy analysis

- the heuristic of the policy cycle.

The term public policy might seem quite simple at first glance. However, as we often find in the social sciences, a concise agreed-upon definition can be very problematic. Who makes public policy? Who shapes the opinion of those decision makers? Is public policy restricted to ‘the decisions to act’ or does it include ‘the decision not to act’? Does/should the study of public policy include the impact of said policies or is it restricted to decision making processes based on the intentions of policymakers?

The second term we look at is the qualifier ‘comparative’. What is the utility in comparing public policy? We will look at how comparing public policy allows decision makers to potentially learn from the successes and failures of other actors in other places. In our increasingly globalized world, the traditional national focus of public policy has been forced to recognize this international context. Some policy issues require international cooperation. Other policy issues, are by necessity made in a globalized context and will impact the economic, social, and political conditions within a state. A comparative approach on public policy is therefore very useful both for policy that requires international cooperation and policy which will have economic, social, or political consequences due to international factors.

Finally, the most common frameowork used in public policy analysis is the policy cycle. While certainly not reflective of all public policy decision making, or arguably even most public policy, it is useful in breaking public policy decision making into distinct stages. This allows us to deconstruct policy to understand what did or did not happen in the decision-making process as well as what could have been done better or differently. By looking at each of these concepts in this module, we will be able to clear some of the conceptual clutter before moving on to the theories of public policymaking in the next module.

Before moving on, let us assess what you believe are the most important public policy issues in Canada today. If we define public policy issues as everything that the government is working on and everything that the wider public is trying to get the government to work on:

- What do you think is the most important national issue for the general public today?

- What is the most important national issue for you today?

You can use some of the following resources to inform your answers:

- A very basic list of Social Issues in Canada today: http://www.thecanadaguide.com/culture/social-issues/

- A longer list of Social Issues in Canada today: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/browse/things/communities-sociology/social-issues

- A very informal (but fascinating!) list of Social Issues: https://www.reddit.com/r/CanadaPolitics/comments/8sp932/what_are_the_most_troubling_economic_and_social/

- A more academic list of projects being funded by the Public Policy Forum: https://ppforum.ca/research-reports/current-research/

- Alternatively, you can speak to your friends, family, or scan the news headlines.

Post your answers to questions 1-2 on the interactive whiteboard (i.e., Padlet) shown here (click on the (+) icon to add your answer to each side).

What is Public Policy?

Public policy is important because the scope of state action extends to almost all aspects of our lives. However, it is one of many terms in political science – like democracy, equality and power – that are well known but notoriously difficult to define. The problem of definition is more than semantic: it affects how we analyze and understand real policy issues. Different definitions, drawing on different aspects of the policy process, give us multiple perspectives. Getting scholars to agree on a single, all-inclusive definition of public policy is no easy task. One of the most frequently cited definitions of public policy is that given by American political scientist Thomas Dye. According to Dye, public policy is ‘whatever governments choose to do or not to do.’ Public policy then involves a conscious choice that leads to deliberate action: the passage of a law, the spending of money, an official speech or gesture, or some other observable act. They may also choose not to act, to make a conscious decision to not move forward, on institutional agenda items for a determined or undetermined period of time. While the literature generally questions our ability to define policy, there is utility in starting with a simple definition. Therefore, for our purposes, we will start by defining policy as ‘whatever government chooses to do or not to do”.

Figure 1-5: EP seeks equal treatment for self-employed Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of European Parliament.

However, this, in turn, gives rise to four key questions. First, does this definition of public policy, ‘whatever the government chooses to do or not to do‘, include what policymakers say they will do as well as what they actually do? Political parties produce manifestos and elected officials produce speeches setting out their policy plans, especially during elections. But should we wait until those plans are carried out until we call them public policy? Sometimes policymakers set out with an aim to create policy and it is difficult to know when that work is substantive enough to constitute a public policy. Can we consider legislation as policy, if the budget required to carry out the policy has not been agreed upon? What about a consultation document that has been prepared to officially set out the government’s plan? This suggests that the identification of substantive policy measures is more of an art than science.

Figure 1-6: Every Canadian Needs A Copy Permission: CC BY 2.0.Courtesy of Marc Lostracci.

Second, does it include the effects of a decision as well as the decision itself? Policy outputs are the formal actions that a government takes to pursue its goals. In this case, policy is a function of what government actually delivers in terms of goods and services or enforcement in the areas of education, health, agriculture, etc. Policy outcomes are the effects such actions have on society. We need to focus on policy outcomes but at the same time also recognize that those outcomes are influenced by factors outside the policymaker’s control. For example, policymakers may put aside money to pay for a policy output such as doctors and teachers. However, they are less able to ensure the desired policy outcome, such as improvement on the health or education of a nation. This is because policy outcomes also rely on the front-line implementers of a policy, on the context within which it is implemented, and even the behaviour of the population as a whole. Further, policymakers are often not sure of the effect their policy instruments may have. We study outcomes because they may not resemble the initial policy aims, however, committed a government is to achieving those aims. Therefore, we also want to look at how decision makers evaluate policy once implemented and how such evaluations work to tweak policy in the next policy cycle.

Figure 1-7: The Economic Crisis – Protests Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0.Courtesy of William Murphy.

Third, what is the government? Does the ‘government’ include elected and unelected policymakers? This speaks to the question of how actors gain membership to the policy process. Some actors may have a recognized source of authority – such as the role of Prime Minister or being a member of the legislature. Other actors in the public policy process may make claims on other sources of authority. Some may have a recognized form of expertise that gives them policy influence, such as members of an epistemic community, interest groups, or civil society. Others may be required to make sure that policy decisions are carried out – such as civil servants. Policy is made by such ‘policy collectivities.’ It is the joint product of their interaction. Therefore, while we must pay specific attention to elected policy makers, we may miss a lot of the picture if we ignore the role of unelected actors.

Figure 1-8: Women’s March on Washington – 1/21/17 Permission: CC BY 2.0.Courtesy of Molly Adams.

Fourth, does public policy include what policymakers choose not to do? Sometimes policymakers ignore an issue actively or they may not pay attention to an issue because they do not consider it to be a policy problem. Take the instance of toxic chemicals in Canada. For years, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were used, stored and disposed of without much care for public safety. The government did not have any public policy to handle PCBs until it realized there was a need to worry about the public’s welfare. Without question, it was a case of the state’s failure to act, though not its decision not to act. Once the public became aware of the cancer-causing effects of PCBs, their elimination, transportation as well as use became an issue of policy. In other cases, however, the government may have information on a potential threat or opportunity to further their respective constituents’ interests but choose not to act on it or at least not in a timely fashion. For example, while the Canadian government began to realize the negative health implications of Asbestos in 1920, it did not ban the manufacture and use of Asbestos until 2018 because of economic and political considerations.

Figure 1-9: 204_0498 Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0.Courtesy of DoctorButtsMD.

So, our initial attempt to provide a simple definition of public policy is replaced by a much longer discussion that highlights complexity. However, in that complexity, we begin to achieve a better grasp of what public policy is, why it is so important to understand the processes involved and the benefit of casting our net wide to learn from the processes of others facing similar policy issues.

Watch the TEDxSHHS video ‘The influence of policy’ by Amy Hanauer: https://youtu.be/iBRxl3Klhj0

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- a) According to Hanauer, what is the one thing that unites the disparate series of questions that parents and academics may have on the future lives of children?

b) Why? - a) What is the dirty secret of public policy?

b) According to Hanauer, what do you need to influence public policy? - How can small changes in public policy have large impacts?

- a) How are we discouraged from asking the important questions of public policy in the US?

b) Does this answer resonate with your view of public discourse in Canada? - a) Do you think public policy is important?

b) If yes, why? And how can you get involved? If no, why not?

What is Comparative Public Policy? Why is it important?

When we travel to new places, we almost automatically and even subconsciously engage in comparisons with how things are done in our own country. It can be an almost overwhelming experience to encounter the different sights, sounds, and language of a new environment. However, when we stand back, we may note that while people are doing things differently, they are seeking to accomplish goals that are quite recognizable. They are seeking to build communities that are healthy, happy, and prosperous. In this, it is possible to recognize that local and national governments around the world are often facing the same dilemmas our governments are faced within our home countries: how best to promote the public interest and how to pay for doing so.

Figure 1-10: Globe head Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Slava Bowman on Unsplash.

The different ways in which governments deal with these dilemmas offer fascinating patterns of similarity and difference. Comparative public policy research investigates these patterns and seeks to understand them. It can help us better understand how policy is made and the policy consequences in other countries or other domestic jurisdictions. This helps us move beyond national and regional stereotypes and toward clarity and awareness of the impact of the local context on decision-makers and on those who implement policy on the front lines. Equally as important, the study of comparative public policy holds the potential to help us illuminate policy processes in our own country, province, and city. Comparative public policy analysis provides free lessons on how to ‘do’ policy differently and allows us to be self-reflective on how things are currently being done in our communities. Comparing public policy in different communities or nations can also provide us with a deeper and richer understanding of the fundamental drivers of policy-making and its impacts on the world. It can indicate where and why public policy trends develop, and why they may be absent in different contexts. It can provide positive examples of public policy that make us question some of the assumptions that we hold, assumptions that may have limited our scope of policy options or policy ambitions. Alternatively, it can provide us with negative lessons, where things went awry, warning policy-makers against making similar and potentially harmful policy choices.

Public policy analysis has typically adopted a national focus. However, the stakeholders involved in designing and delivering public policy, and the subsequent policy outcomes, vary significantly across nations. We would certainly anticipate this in the fields of culture or language, where we would expect policy to be governed differently in various nations. Similarly, we might expect policy differences between nations that are able to extract significant funds from their populations through taxation when compared with less economically developed countries. Yet even among relatively similar countries with seemingly identical aims, we can find radically divergent policy approaches. One example is the field of health care policy. All modern governments say they want to see improved indicators of health care. No one wants the health of their population to deteriorate or the quality of health care to diminish. Despite these similar basic aims across countries, health care is delivered in many different ways across nations. In some countries, health care is provided entirely by private organizations and in other countries, it is almost entirely undertaken by public organizations. In some countries health care is paid for through universal taxation, in other countries, it is paid through social insurance, private insurance, or through payments ‘at the point of use.’ In some countries, medical interest groups drive policy-making on health care. In other countries, their policy-making role is considerably less significant. This diversity persists even given the very basic policy aims all countries share.

Figure 1-12: Electrocardiogram Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Jair Lázaro on Unsplash.

In some cases, the typical national focus has increasingly had to give way to international considerations. Some policy issues, like the environment, often require a degree of international coordination to craft effective policy. For example, Canada and the United States have a long history of cooperating on environmental policy, with the earliest being the Boundary Water Treaty (1909). Other issues, like Climate Change, operate at a truly global level and require much broader multilateral cooperation. National policy has also come under pressure because of globalization. Our increasingly globalized economy has applied pressure on decision-makers to find market efficiencies to increase competitiveness and to better attract both financial and human capital. This has forced decision makers to re-evaluate their policy goals as well as their processes for making public policy. Thus, in comparative public policy analysis, we can compare policy both intra-nationally and internationally. Intra-national public policy analysis may compare policy inputs, processes, and outputs between British Columbia and Saskatchewan or Saskatoon and Regina. International public policy analysis may compare policy inputs, processes, and outputs between similar countries like Canada and Australia or very different countries like Canada and Brazil. In both intra-national and international comparative public policy, the goal is to contrast policy determinants, policy content, policy processes, and policy effects. In so doing, we look for what is similar and what is different. We look for what was successful and what was not. We look for explanations to explain both the similarities/differences and successes/failures.

National, regional and local governments thus adopt a great deal of variety of approaches toward similar policy problems. The impacts of analogous policies vary significantly depending on their societal, cultural and national context. Politics and policy work in distinctive ways in different nations, regions and towns. This highlights the contrast between social research and the study of natural sciences. Causal relationships in the natural sciences are always the same, provided the relevant variables are held constant: gravity always works the same way, no matter where one is in the world. In contrast, human societies are so diverse that there is no such thing as a universal ‘social law’ within the social sciences. There is agency at work, with different people in different places finding different policy options to issues that are commonly held. In comparative public policy analysis, we compare and contrast these policy choices. The value of such comparisons is two-fold. First, comparative public policy allows us to reflect on our policy processes, choices, and outcomes. Second, it allows us to widen our policy horizons and perhaps think outside the box when trying to achieve our policy goals. In an increasingly complicated and interdependent world, such self-reflection and policy creativity is highly useful.

First, read the Atlantic article “Canada Is Raging Against Gun Violence—But Not Like America” https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/07/canada-gun-control-debate/566102/

Next, watch the AJ+ video “Canada Vs. USA: Who Does Gun Control Better?” https://youtu.be/zE0MiJeCzN0

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How does gun-related violence in Canada compare to the United States?

- What explains the difference between the US and Canada?

- Why does Cukier argue for stronger gun control laws in Canada?

- Why does Friedman oppose stronger gun control laws in Canada?

- Why/How do US gun laws and US lobbies like the NRA influence the debate in Canada?

- How does the AJ+ video explain the differences between gun control in Canada and the US?

- a) Using evidence from both the video and the reading, what can the US and Canada learn by comparing gun control policy?

b) Do you think Canada or the US will change their respective gun control policies based on what could be learned from such a comparison?

c) Why or why not?

The Policy Cycle

As should be clear by now, public policy-making is complex – it is the culmination of a lot of moving parts. A policy issue has to be recognized by an authoritative actor as something that needs to be considered. Decision makers then need to choose if this is something they want to act on and, if they do, what the goal of a policy response would be. There needs to be a means to choose the best policy option and how to implement it once chosen. There needs to be a means to check if the policy is resulting in the desired outcome and, if not, what to do about it. This is further complicated by the fact that very few if any policies are tabula rasa – crafted on a clean slate. Rather, most policies are crafted from a complex milieu of past policies, often written and implemented by other actors – many of whom may have had a different ideological perspective than the decision makers in the current government. Even within the same government, different departments and officials are often involved in the evolving implementation of policies. These separate processes of policy implementation often manifest small differences in policy understanding, creating different policy trajectories, and over time may result in critical inconsistencies that undermine the very purpose of a policy. Another issue is that these existing policies have created incentives and disincentives for a long list of actors. Take tax policy for example. Individuals and businesses alike shape their economic activity, their medium to long-term planning, and investment decisions on the current tax policy. If a new government wants to change the tax policy, as Prime Minister Trudeau and his Finance Minister Bill Morneau did in 2017, they will upset the status quo. Some will benefit and some will not, but most people and businesses will have to adjust, and this creates a degree of uncertainty, angst, and cost. Further, jurisdictional differences between the Federal and Provincial Governments may lead to offsetting policies. This highlights the fact that there are complicated economic and political implications in making policy decisions.

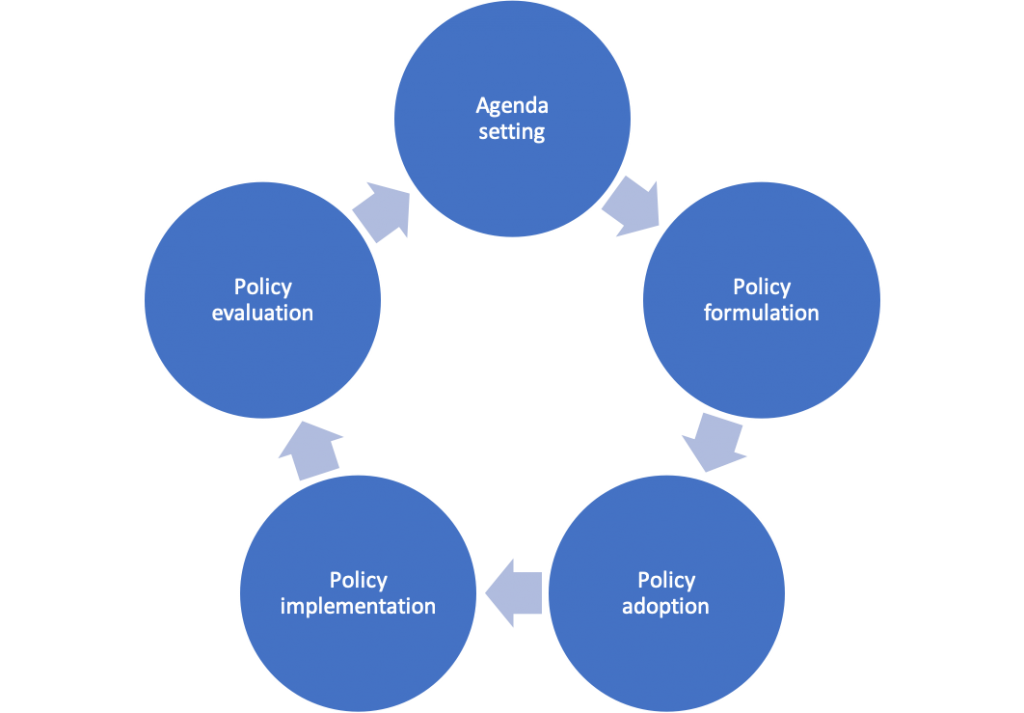

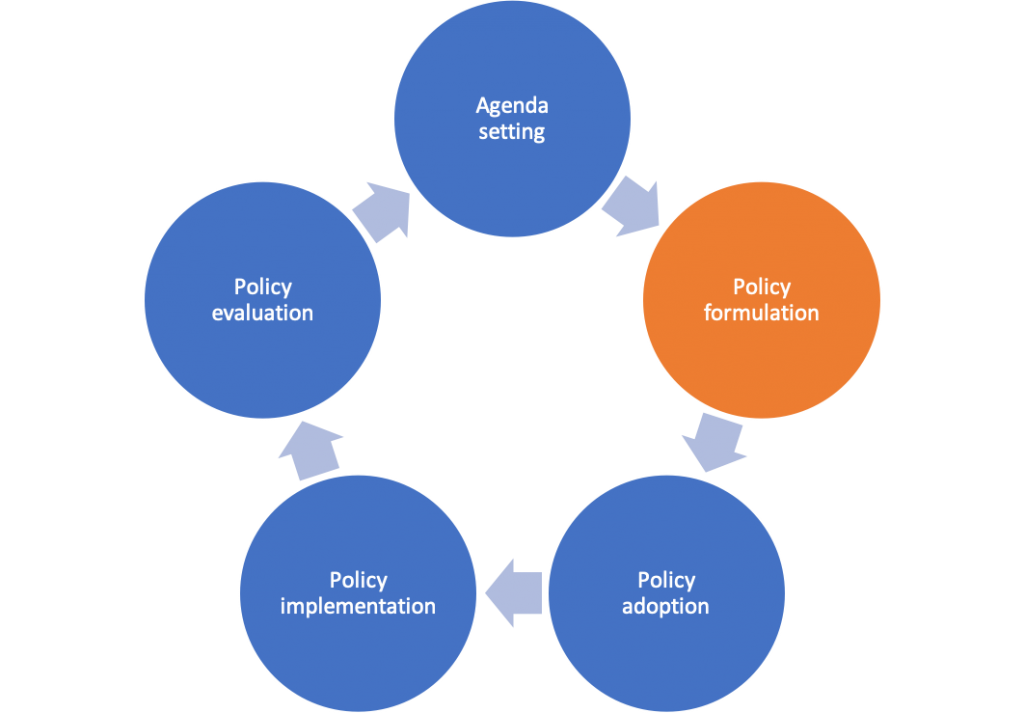

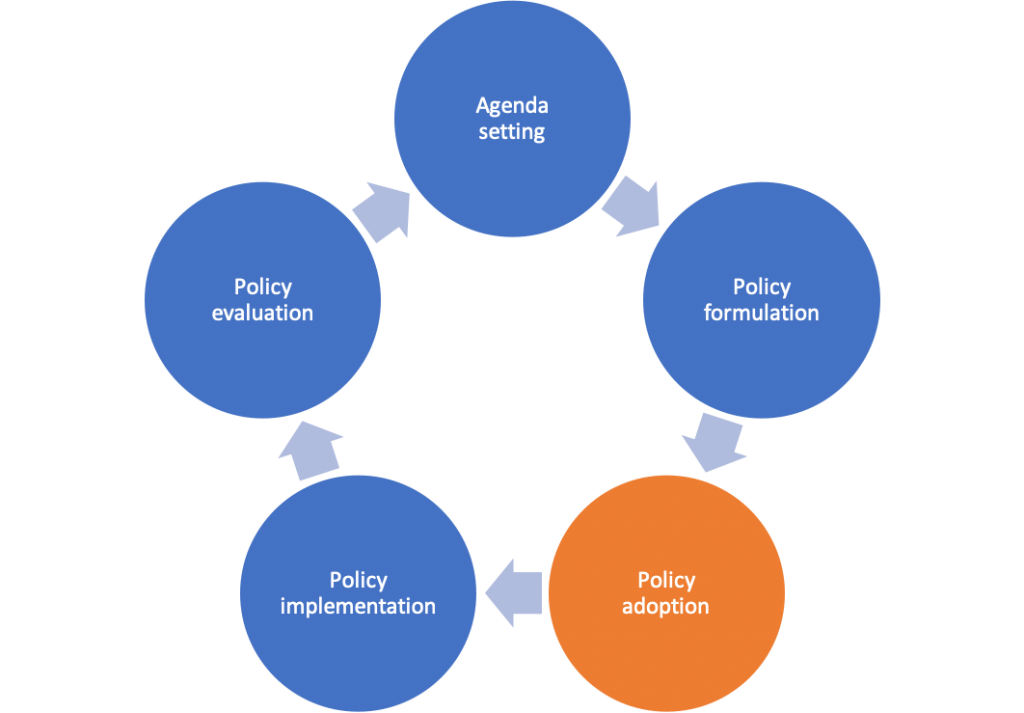

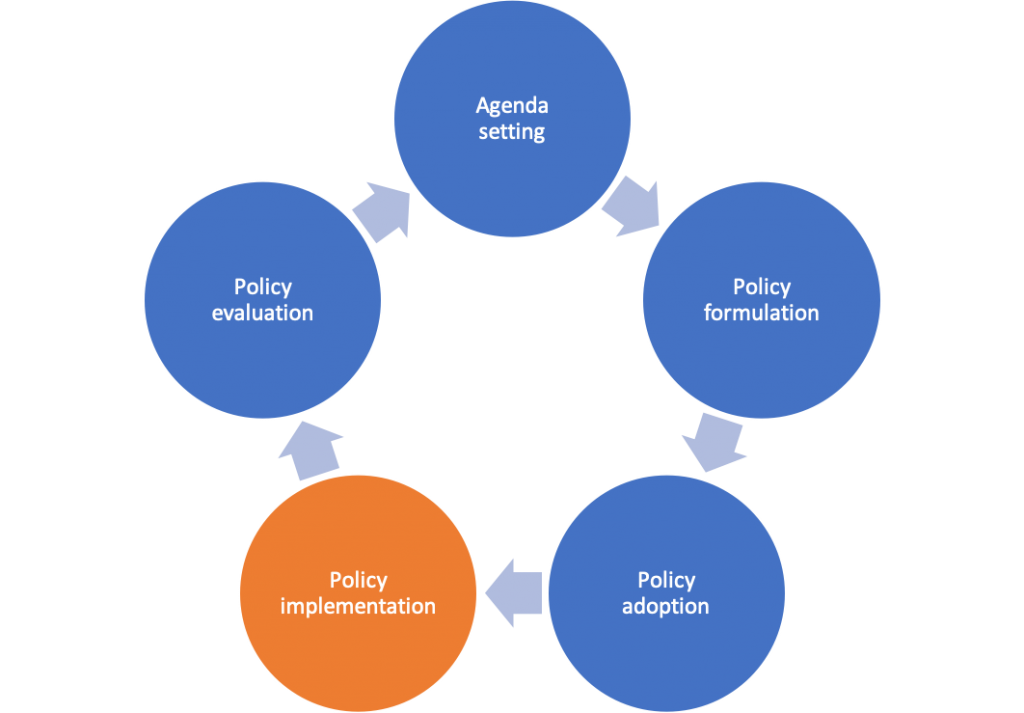

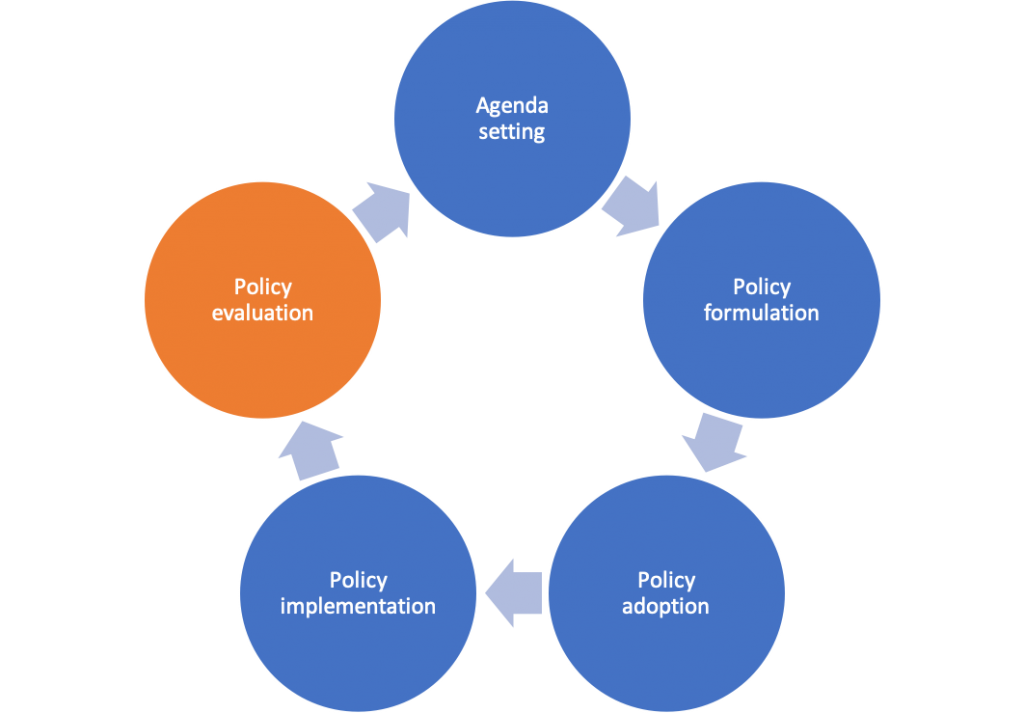

Figure 1-13: Five stages of the policy cycle. Permission: Courtesy of Distance Education Unit (DEU), University of Saskatchewan, based on Miles (2012).

In order to make sense of some of this complexity, the process of policy-making is often broken down into a series of stages using a heuristic called the policy cycle. Before introducing the policy cycle, it is important to highlight that this is a heuristic – or a simplification device to aid in understanding the different aspects of policymaking. This can be misleading. Policy rarely, if ever, neatly begins in stage one and proceeds linearly. It is often much more haphazard, moving forward and backwards through the stages we are about to introduce. Policymaking may even skip steps due to contextual contingency factors – economic disruption, political crisis, or the sudden escalation of a policy problem. However, with that being said, the policy cycle is very useful in understanding how a policy comes to be. It allows us to look at what happened or should have happened at particular points of policymaking. It allows us to see what worked and what didn’t. It allows us to look at what was done differently in other places and try to assess what the implications of those differences are to policy outcomes. Most of all, it allows us to try and figure out what to do the next time. And this is an important insight – policy rarely stops. After a policy has been put in place, it will generate its problems and issues that need to be addressed. Depending on the severity of the issues that manifest, the policy may need minor in-house tweaking, or it may require such extensive revision that it becomes a political issue that is brought forward as an electoral issue. In either case, it is best to view public policy as an iterated exercise – a continual process of reflection, tinkering, or even wholesale reconstruction. There are different descriptions of the policy cycle with a different number of stages identified. For the purpose of our class, we are going to use the simple five-stage policy cycle:

- agenda setting,

- policy formulation,

- decision making,

- implementation

- evaluation.

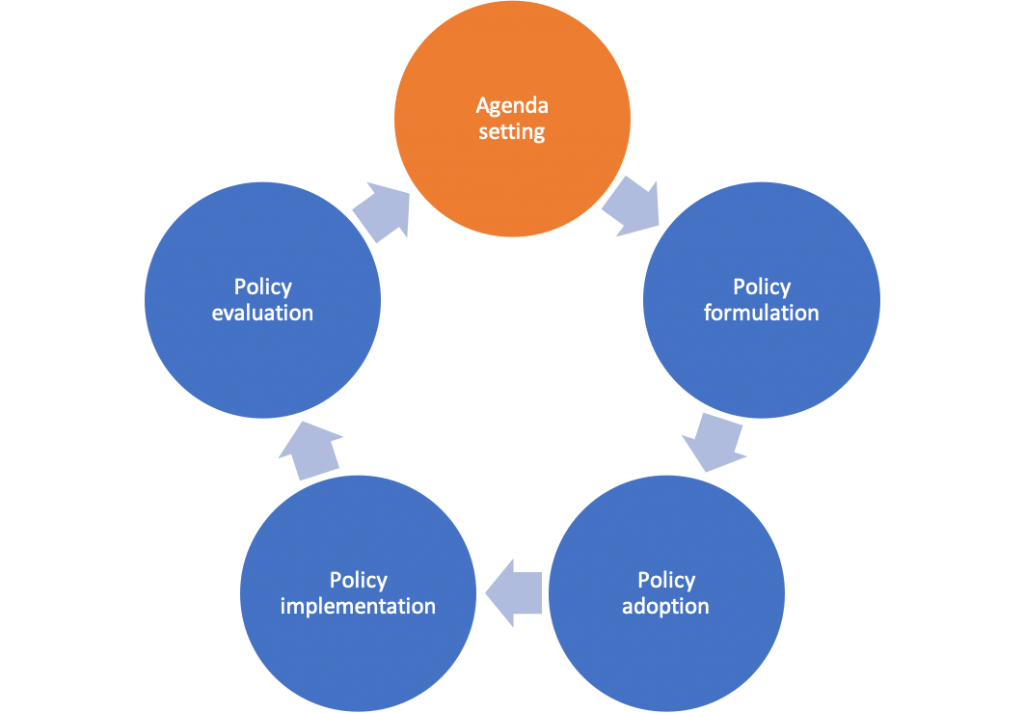

Figure 1-14: The agenda setting stage of the policy cycle. Permission: Courtesy of Distance Education Unit (DEU), University of Saskatchewan, based on Miles (2012).

Agenda setting is the first stage of the policy cycle. It is a process by which different actors seek to have an issue, which they believe to be important, put before authoritative decision makers to be addressed. An important distinction can be made here between an institutional agenda and a public or systemic agenda. A public agenda or systemic agenda is informal and refers to those issues which resonate within the wider body politic. These are the issues you see on the nightly news or being discussed on social media. The more widely an issue is discussed, the higher it moves on the public agenda as it becomes something that the public believes the government ‘should’ do. For example, we currently see issues like pipelines, irregular migration, and Indigenous rights being broadly debated. These are issues that spark both public debate and have interest groups actively promoting them. If an issue moves high enough on the public agenda, it is likely to become an issue the government feels it will need to address. The list of issues that the government formally recognizes is called the institutional agenda. This institutional agenda contains more than those issues that were elevated on the public agenda. It also includes those issues that the government itself believes to be important. These could be issues that they campaigned on – think of President Trump and his proposed US-Mexico border. Or they could be issues that develop suddenly – think of the Trudeau Government’s need to deal with irregular migration as changes to American immigration policy drove a large increase in asylum seekers crossing the Canada-US border. In both the case of the public agenda and the institutional agenda, several things need to be present for an issue to successfully move on to the next stage of the policy cycle. First, there must be a person, or more likely a group, that acts as a champion for the issue, arguing that it warrants attention. Such champions can be from within government, for example, a Minster who identifies something in their policy area that they believe needs the attention of the cabinet. Or it can be an outside actor, for example, an interest group who advocates on behalf of an issue they believe to be of importance. Second, in order to motivate the government to act, the issue must contain a threat or an opportunity. Just because an issue makes it onto the institutional agenda, it does not mean that the government will choose to act on it – in fact, the government may consciously decide not to act on it. For a government to act on an issue that has made it onto the institutional agenda, it must believe there is an advantage in doing so. They must recognize it as a problem more important or as an opportunity offering greater advantage than competing issues. This is the very definition of politics: the allocation of scarce resources in a given political community. In order to make this determination, an issue must have identifiable, even if initially vague, policy solutions. Finally, the government must believe that there is a realistic chance of achieving one of these existing policy solutions – it must be economically and politically feasible. If all of this holds true, the policy may move to the next stage of the policy cycle – Policy formulation.

Figure 1-15: The policy formation stage of the policy cycle. Permission: Courtesy of Distance Education Unit (DEU), University of Saskatchewan, based on Miles (2012).

Policy formulation is the stage where the government formally decides to explore policy options that can address the issue under discussion. This process often begins with an appraisal step, with a call for expert testimony and data. The government may commission policy reports, call for expert witness testimony, seek input from important stakeholders, and/or seek public consultation. The breadth and depth of this review will depend on the potential economic/political costs/benefits involved. For example, if the government is considering a new payroll system, they will likely restrict enquiries to input from service providers and the internal departments affected. That being said the Harper and Trudeau governments might have wanted to take a bit more time in changing over to the Phoenix pay system given the debacle it has become. On the other hand, if the government is seeking to change our electoral system, there will likely be extensive consultations, and a wide range of input will be sought after unless the decision making is simply pro forma – though that in itself is noteworthy. Once all the data is collected, there will be a period of dialogue with policy experts and stakeholders. They will be presented with summaries and asked for their thoughts on what might work/is acceptable and what is problematic/unacceptable. This dialogue can be formal with experts asked to provide their assessment on the pros and cons of particular options. They can also be informal with open meetings held to discuss options as they coalesce. From the early appraisals and subsequent dialogue, government bureaucrats will be tasked with drafting possible policy formulations. These policy formulations are often provided to stakeholders for feedback as they evolve and may generate substantive resistance from those who believe their concerns are not being addressed. However, this too is important – as the various formulations are consolidated into a relatively stable set of choices, decision makers are able to see who will support/oppose particular positions. The policy will move to the next stage if the government believes a policy option is feasible in terms of potentially addressing the issue. If it is a good use of resources both economically and relative to competing issues. And if it is achievable given the political climate of the population at the time. If all these conditions are met, we move to the decision-making stage also known as the policy adoption stage.

Figure 1-16: The policy adoption stage of the policy cycle. Permission: Courtesy of Distance Education Unit (DEU), University of Saskatchewan, based on Miles (2012).

Decision making or policy adoption is the narrowest and the most overtly political stage of the policy cycle since it only includes those with the authority to make a binding choice. Consequently, it is also the stage in the policy cycle with the most room for ‘actorness’: where the government can act in accordance with its own goals and interests rather than on procedural or technical issues. This is where the government must reflect on all the pros and cons of the various policy formulations and decide to act or not. First, they can decide not to act. This is more likely if the cost is high economically, politically, or relative to other options. A negative outcome is also more likely if the government is able to claim a victory for investigating policy options even if they would prefer not to address the issue substantively. Second, they can restart the policy cycle by sending the issue back to the policy formulation stage or by essentially putting it on-hold by keeping it on the institutional agenda but as a lower priority. This option is more likely if the government is on the fence, waiting to see how public opinion unfolds or is overwhelmed by the number of items on the institutional agenda. Third, they can choose to act by selecting one of the policies that emerged from the policy formulation stage or some combination thereof. This is a critical choice in that by doing so, the government must stipulate what policy they are going forward with, why they are going with that policy, how they will put it into place, and what they hope to achieve. In a very real sense, they are laying their cards on the table. Now, they move to the next stage – policy implementation.

Figure 1-17: The policy implementation stage of the policy cycle. Permission: Courtesy of Distance Education Unit (DEU), University of Saskatchewan, based on Miles (2012).

Policy implementation is the stage where the number of actors once again increases to include the different levels of government bureaucracy and agencies that will be involved. It may include a judicial component if any aspect of the policy is controversial or possibly unconstitutional. If it is at all controversial, it will become fodder for the opposition party and for those interest groups that are unhappy with the substance of a policy or its procedural form. However, the most important actors at this stage are the senior civil servants who will translate the policy choice of the government into working regulations or administrative rules. This can happen in either a top-down or bottom-up fashion. In a top-down implementation, there is very little wiggle room as the policy has been crafted in a very precise fashion to meet specific goals in a specific way. The question here is whether there are sufficient mechanisms for public servants to effectively implement policies. In a bottom-up implementation, the overarching mechanism and goals of a policy are laid out but there is significant room for adapting or interpreting policy by the bureaucracies involved. A bottom-up approach does allow a greater degree of manoeuvrability, but it comes with a risk if there is any resistance to the policy goals within the bureaucracies or if there are insufficient resources to achieve the intent of the policy. Regardless of the form of implementation, the next step in the policy cycle is policy evaluation.

Figure 1-18: The policy evaluation stage of the policy cycle. Permission: Courtesy of Distance Education Unit (DEU), University of Saskatchewan, based on Miles (2012).

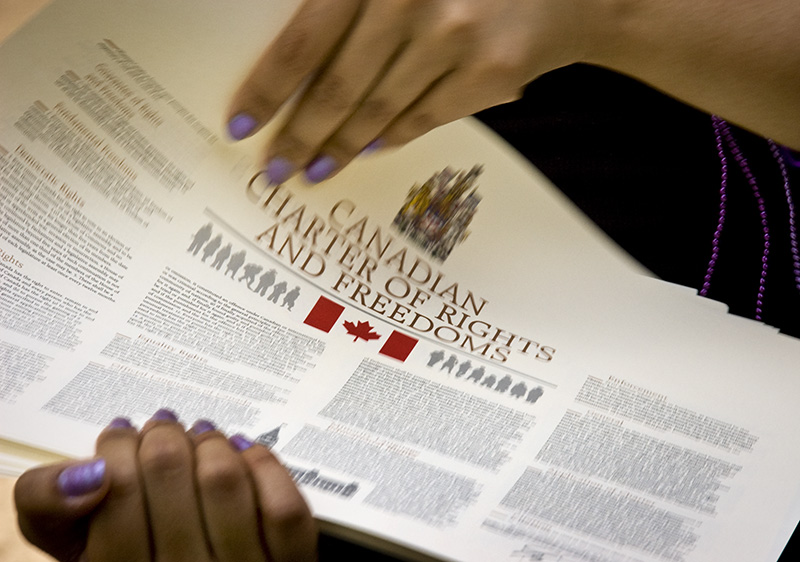

Policy evaluation is the stage where the impact of the policy is assessed against the stated intent of the policy – did it do what the government said it was going to do and within or close to the budget estimates. There are three principal forms of evaluation: administrative, judicial, and political. First, administrative evaluations are usually undertaken in-house through a series of evaluation tools. A process evaluation will measure the organizational efficiency of policy delivery – was the policy delivered efficiently, effectively, and with accountability. An effort evaluation will assess program inputs by creating a baseline of costs, such as capital and operating expenditures. A performance evaluation will assess program outputs – what did the policy produce. An efficiency evaluation will combine the benchmarks established via the effort and performance evaluations to assess the worth of a program – did the policy deliver on its promises at a reasonable cost. Finally, an effectiveness evaluation will assess whether the policy fulfilled its mandate. Second, judicial evaluations are undertaken to measure the legal authority of a policy once implemented. It can determine whether an agent has exceeded their authority in an arbitrary or unreasonable way. It can ask if the policy has contravened the division of policy jurisdiction constitutionally established between the provincial and federal governments. Finally, a judicial evaluation can ask whether the substance or procedure of a policy has violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Third, political evaluations are taken by all politically active actors, including the government, the opposition, and all stakeholders. It seeks to evaluate the political appropriateness of a policy. Are voters happy with the intent and outcome of a policy? Has the political climate changed to make a policy more or less attractive? This type of evaluation is most likely to occur around electoral activity.

As noted earlier, while the policy cycle may suggest that all policy progresses in a linear way through these 5 steps, that is a very simplified view of policymaking. An existing policy may undergo an internal evaluation that raises an issue to be addressed at a technical level. Another policy may not substantively be debated since the government already has a preferred option and they believe they can implement it without too high a political cost. But it is useful to look at a policy through the lens of the policy cycle to see what worked, what did not, what was done differently elsewhere, and what could be learned going forward.

First, read Dale Eisler’s article “The grim reality of Canada’s biggest policy failure”

In order to answer the following questions, you may need to do some cursory research online. However, do not be too bogged down on the details, but do ensure your statements are at the very least generally accurate. The goal here is to think about a given public policy as part of an iterated cycle

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal. Imagine that you are working for the Canadian Government that has received this dismal evaluation of the existing Indigenous and Aboriginal policy. Apply the logic of the policy cycle.

- a) What would an evaluation of the existing policies look like?

b) Given the various tools at your disposal, how might the policy be evaluated? - Who might be advocating for new policy choices to be put on either the public or institutional agenda?

- Choose one of the policy suggestions in the article. What would be two possible policy formulations that emerge?

- What might be some of the considerations that the government might contemplate before making a decision to act or not to act?

- Who would be involved in the implementation of the policy?

As we have seen in this module, becoming analysts or makers of public policy is not as straightforward as it might seem when we are debating issues as the general public. In order to set a foundation for moving forward in this class, we have sought to establish some working definitions and heuristics. We began by defining public policy as ‘whatever a government chooses to do or not to do.’ However, we also recognized that this definition raises some important questions that we need to keep in mind going forward. Is the rhetoric of the government important or only what they actually do? Are the effects of policy outputs important or only the intention of policymakers? Should public policy analysis be restricted to the purview of official government officials? Or should it include other people who shape or seek to influence public policy? Is the choice not to act as significant as acting on an issue? By recognizing the complexity of public policy-making, we are better able to comprehend what public policy is and therefore undertake better analysis.

We also looked at what it means to add the qualifier ‘comparative’ to our study of public policy. We noted that using comparative frameworks allows policymakers and analysts of public policy to learn from others by asking questions. Why did this actor choose this policy and another actor chose a different policy to address a similar policy issue? How does our increasingly globalized world require more comparative approaches to public policy? What can we learn by comparing public policy? What can be adopted from what we learn from such comparative analysis?

Finally, we introduced the heuristic of the policy cycle. We looked at how agenda setting occurs both at the systemic and institutional levels. We noted what is needed to move from the agenda setting stage to the policy formulation stage: namely, a champion for a policy, a reason to motivate official action by decision makers, a relative advantage to addressing this policy over others, and a realistic option of adopting a solution with a reasonable cost. After agenda setting, a policy issue requires options or policy formulations for decision-makers to consider. The process of policy formulation is constituted by data collection, expert witnesses, and consultations with stakeholders. Once a stable set of policy formulations emerges the government can choose to act or not to act. This is the narrowest stage of policy-making and the least technical as is it more about whether it is in the interest of the government to act. If the government chooses to implement a policy, the lead is handed over to bureaucracies and civil servants albeit with varying degrees in autonomy in interpreting the policy and its goals. Finally, once implemented the policy may undergo various kinds of evaluation, most notably administrative, judicial, and political. And then the process starts all over again with advocates and detractors within and outside government pushing items on the systemic or institutional agenda.

In the next module, we will be looking at some of the theories and frameworks of public policymaking.

Review Questions and Answers

One of the most frequently cited definitions of public policy is that given by American political scientist Thomas Dye: public policy is ‘whatever governments choose to do or not to do.’ Policy then involves conscious choices that lead to deliberate action. Examples of such deliberate action include drafting and passing legislation, spending money, giving an official speech, or some other observable act. Another deliberate action included choosing not to act, a conscious decision to not move forward with an issue on the institutional agenda for a determined or undetermined period of time. Public policy, and the study of public policy, is extremely important since it shapes every aspect of our lives, from how much we pay for tuition to the form our electoral system takes – and everything else in between.

While it is useful to have a simple working definition of public policy, it can also oversimplify things. Our working definition stipulates public policy is whatever governments choose to do or not to do. This is a useful definition as it highlights two important aspects of public policy, the who and the what: the government as the most important actor and a focus on deliberative action. But the complexity of public policy raises some questions not answered by this definition. Specifically, we detailed four:

- Is the rhetoric of the government important or only what they actually do?

- Are the effects of policy outputs important or only the intention of policymakers?

- Should public policy analysis be restricted to the actions of official government officials? Or should it include other people who shape or seek to influence public policy?

- Is the choice not to act as significant as acting on an issue?

Undertaking public policy analysis in a comparative fashion provides two main benefits:

- First, it provides ‘free lessons’ on how to make policy differently and provides insight about how things are done in our own country, comparing public policy in different communities or nations can also provide us with a deeper and richer understanding of the fundamental drivers of policy-making and how it impacts on the world. It can indicate where and why public policy trends develop, and why they may be absent in different contexts. It can provide positive examples of public policy that makes us questions some of the assumptions that we hold, assumptions that may have limited our scope of policy options. Alternatively, it can provide us with negative lessons, where things went awry, warning policy-makers against making potentially harmful policy choices.

- Second, as our world becomes increasingly globalized the comparative aspect of public policy also becomes more important in two ways:

- First, some policy issues require cooperation between states. This, in turn, may require some harmonization of policy to be effective. A comparative approach to public policy analysis is useful in such cases.

- Second, as capital, finance, and to a lesser degree labour becomes increasingly mobile, national policy may make a state more or less competitive on the global stage. It is therefore important for governments to account for the policies of other states in order to make the best policy choices.

A public or systemic agenda is informal and refers to those issues which resonate within the wider body politic. These are the issues you see on the nightly news or being discussed in social media. The more widely an issue is discussed, the higher it moves on the public agenda as they represent what the public believes the government ‘should’ do. For example, we currently see issues like pipelines, irregular migration, and Indigenous rights being broadly debated. These are issues which both spark public debate and have interest groups actively promoting them. If an issue moves high enough on the public agenda, it is likely to become an issue the government feels it will need to address.

The list of issues that the government formally recognizes is called the institutional agenda. This institutional agenda contains more than those issues that were elevated on the public agenda. It also includes those issues that the government itself believes to be important. These could be issues that they campaigned on – think of President Trump and his proposed US-Mexico border. Or they could be issues that developed suddenly – think of the Trudeau Government’s need to deal with irregular migration as changes to American immigration policy drove a large increase in asylum seekers crossing the Canada-US border.

Decision making is the narrowest and the most overtly political stage of the policy cycle since it only includes those with the authority to make a binding choice. Consequently, it is also the stage in the policy cycle with the most room for ‘actorness’: where the government can act in accordance to its own goals and interests rather than on procedural or technical issues. This is where the government must reflect on all the pros and cons of the various policy formulations and decide to act or not. While this is the narrowest stage of the policy cycle it is also the most important. This is where the final decision is made, at least at this time, on whether to go ahead, not go ahead, or ask for new policy formulations. Importantly, if the government decides to move ahead, they must stipulate what policy they are going forward with, why they are going with that policy, how they will put into place, and what they hope to achieve. In a very real sense, they are laying their cards on the table.

There are three principal forms of evaluation: administrative, judicial, and political.

First, administrative evaluations are usually undertaken in-house through a series of evaluation tools. A process evaluation will measure the organizational efficiency of policy delivery – was the policy delivered efficiently, effectively, and with accountability. An effort evaluation will assess program inputs by creating a baseline of costs, such as capital and operating expenditures. A performance evaluation will assess program outputs – what did the policy produce. An efficiency evaluation will combine the benchmarks established via the effort and performance evaluations to assess the worth of a program – did the policy deliver on its promises at a reasonable cost. Finally, an effectiveness evaluation will assess whether the policy fulfilled its mandate.

Second, judicial evaluations are undertaken to measure the legal authority of a policy once implemented. It can determine whether an agent has exceeded their authority in an arbitrary or unreasonable way. It can ask if the policy has contravened the division of policy jurisdiction constitutionally established between the provincial and federal governments. Finally, a judicial evaluation can ask whether the substance or procedure of a policy has violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Third, political evaluations are taken by all politically active actors, including the government, the opposition, and all stakeholders. It seeks to evaluate the political appropriateness of a policy. Are voters happy with the intent and outcome of a policy? Has the political climate changed to make a policy more or less attractive? This type of evaluation is most likely to occur around electoral activity.

Glossary

Actorness: is where a collective performs as a singular actor, often expressing or acting on its own interests. In public policy, the government is an example of a collective performing as a singular actor. In the policy cycle, it is in the decision-making stage where the government displays the most actorness.

Administrative evaluations: are a form of assessment normally taken in-house through a series of evaluation tools including process evaluations, effort evaluations, performance evaluations, efficiency evaluations, performance evaluations, and effectiveness evaluations.

Agenda setting: is the process of advocating for particular issues to be addressed by the government. It can occur either less formally in society at large or more formally on a governments policy to do list. (see public agenda, systemic agenda, institutional agenda).

Bottom-up implementation: sets out the overarching mechanism and goals of a policy but allows for significant adaptation or interpretation of a policy by the bureaucracies involved. A bottom-up approach does allow a greater degree of manoeuvrability, but it comes at a risk if there is any resistance to the policy goals within the bureaucracies or if there are insufficient resources to achieve the intent of the policy.

Civil servant: is a person employed in the public sector by a government department or agency.

Comparative public policy: is the systematic study of public policy which involves comparing across different systems and institutions, paying particular attention for similarities and difference between policy issues, objectives, and substantive policies.

Decision-making stage: is the narrowest and the most overtly political stage of the policy cycle since it only includes those with the authority to make a binding choice (see Policy adoption).

Epistemic community: is a network of experts who can provide advice to policymakers and decision makers to define problems, provide data, and offer policy solutions.

Globalized world: refers to the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, politics, and social relations.

Heuristic: is a device which provides a simplified means of analysis or problem solving.

Interest groups: is a group of people that organize with the express purpose to influence public policy.

Institutional agenda: the list of issues that the government formally recognizes. It contains more than those issues that were elevated on the public agenda. It also includes those issues that the government itself believes to be important.

Iterated: is a circular process. In terms of the policy cycle, it refers to the idea that once a policy cycle has finished the stage of evaluation, the process begins anew with agenda setting.

Judicial evaluations: are undertaken to measure the legal authority of a policy once implemented. It can determine whether an agent has exceeded their authority in an arbitrary or unreasonable way. It can ask if the policy has contravened the division of policy jurisdiction constitutionally established between the provincial and federal governments.

Policy adoption stage: is the narrowest and the most overtly political stage of the policy cycle since it only includes those with the authority to make a binding choice (see decision-making stage).

Policy cycle: is a simplified model (see heuristic) to make sense of the policy-making process. There are several types of policy cycles but, in this class, we are looking at the 5 stage process that includes: agenda setting, policy formulation, decision-making, policy implementation, and policy evaluation.

Policy evaluation: is the stage where the impact of the policy is assessed against the stated intent of the policy – did it do what the government said it was going to do and within or close to the budget estimates.

Policy formulation: is the stage where the government formally decides to explore policy options that can address the issue under discussion.

Policy implementation: is where a policy by the government is put into effect. It is the stage where the number of actors once again increases to include the different levels of government bureaucracy and agencies that will be involved.

Policy outputs: are the formal actions that government takes to pursue its goals.

Political evaluations: seek to evaluate the political appropriateness of a policy and are used by all politically active actors, including the government, the opposition, and all stakeholders.

Politicians: are the elected decision makers with formal responsibility for complex, intricate subsystems of participants and players.

Pro forma: is something done or produced as a matter of form and with little effort or attention.

Public agenda: is informal and refers to those issues which resonate within the wider body politic (see also systemic agenda).

Public policy: is, in its simplest form, is whatever governments choose to do or not to do.

Systemic agenda: is informal and refers to those issues which resonate within the wider body politic (see also public agenda).

Tabula rasa: is a clean slate on which policy can be created without any reference to preceding policy.

Top-down implementation: refers to the delivery of public policy that has been crafted in a very precise fashion to meet specific goals in a specific way. The question here is whether there are sufficient mechanisms for public servants to effectively implement policies.

References

Colebatch, Hal. "What Work Makes Policy?" Policy Sciences 39, no. 4 (2006): 309-21.

Dye, Thomas R., and Virginia Gray. "Determinants of Public Policy: Cities, States, Nations." Policy Studies Journal 6, no. 1 (1977): 84-93

Dye, Thomas R., Gray, Virginia, and Policy Studies Organization. The Determinants of Public Policy. Policy Studies Organization Series. Lexington, Mass.; Toronto: Lexington Books, 1980

Ireton, Julie. “As federal Phoenix payroll fiasco hits 2-year mark, families continue to bear brunt of it.” CBC, Feb 21, 2018.

McConnel, Allan. "Policy Success, Policy Failure and Grey Areas In-Between." Journal of Public Policy 30, no. 3 (2010): 345-62.

Pierson, Paul. "The Costs of Marginalization: Qualitative Methods in the Study of American Politics." Comparative Political Studies 40, no. 2 (2007): 146-69.

Rose, Richard. Ministers and Ministries: A Functional Analysis. Oxford [Oxfordshire] : New York: Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press, 1987.

Ruff, Kathleen, and John Calvert. "Rejecting Science-based Evidence and International Co-operation: Canada's Foreign Policy on Asbestos under the Harper Government." Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, no. 2 (2014): 131-45.

Smith, Kevin B., and Larimer, Christopher W. The Public Policy Theory Primer. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2009.

Supplementary Resources

- Dunn, William N. Public Policy Analysis: An Introduction. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1981.

- Howlett, Michael, and Ramesh, M. Studying Public Policy : Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems. Don Mills ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Peters, B. Guy. "Comparative Politics and Comparative Policy Studies: Making the Linkage." Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice20, no. 1 (2018): 88-100.

- Thissen, Wil A. H., Walker, Warren E. Editor, and SpringerLink. Public Policy Analysis: New Developments. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science, 179. 2013