Developed by:

Dr. Martin Gaal – University of Saskatchewan

Sharmi Jaggi – University of Saskatchewan

Overview

In the first two modules, we set the context of this course. In Module 1, we defined the field of public policy, the function and role of comparative studies, and the broad scope of the policy cycle. In Module 2, we introduced a range of theoretical approaches to Comparative Public Policy, including John Stuart Mill’s method of agreement and method of difference, the cultural school, the economic school, the political school, and the institutional school. Together, these two modules set the broad boundaries of what we are investigating in this course. In the next three modules, we will be looking in-depth at three elements that are important mutually constitutive elements of the policy environment:

1. Institutions: both formal organizations and the informal patterns of rules, norms, and practices that shape the behaviour of actors.

2. Interests: a wide range of forces that create contextual frames that motivate both individuals and organizations to be deliberate and act in particular ways.

3. Ideas: both conscious and sub-conscious frames that shape beliefs and subsequently constrain or facilitate new ideas as policy solutions.

Figure 3-1: Institutions. Parliament Hill, Ottawa https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Centre_Block_and_Centennial_Flame_(14766251442).jpg Permission; CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Tony Webster. |

Figure 3-2: Interests. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/analysis-pay-businessmen-meeting-680572/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt. |

Figure 3-3: Ideas. Source: https://www.pexels.com/photo/black-and-brown-wooden-wall-decor-1811996/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of rawpixel. |

Taken together, these three elements deeply influence the public policy process. Institutions set the framework within which public policy is made, implemented, and evaluated. Interests both directly and indirectly influence what actors believe to be the appropriate action for individuals, the institutions they work in, and the institutions that represent them. As we will see, ideas influence how we see the world, how we see our role in the world, and what is the appropriate action for ourselves and others, particularly in the specific roles being enacted. In this module, we will be examining this last constitutive element in detail – the role of ideas.

Figure 3-4: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/health-care-medicine-healthy-2082630/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of ar130405.

However, it is important, to begin with, a caveat – it is neither a simple task nor an honest one to argue that ‘ideas,’ in isolation, explain policy outcomes. Ideas shape and are shaped by interests, the subject of our next module. For example, when ideas come into conflict, say on health care policy, a number of stakeholders will hold clashing positions that are deeply embedded with specific interests. Doctors, patients, governmental bodies, pharmaceutical companies, and taxpayers will all be influenced by different, contextual, and possibly conflicting interests. This, in turn, may lead them to believe their ‘ideas’ or the ‘ideas’ of people they support are right, good, and proper. A similar argument can be made about institutions. In the given example of health care reform, doctors, patients, governmental bodies, pharmaceutical companies, and taxpayers are all influenced by the institutional structures within which they reside. Their recommendations are shaped by their institutional perspective. Further, the means to change existing policies must work through the existing institutional structures. And these institutional aspects are also connected to stakeholders’ interests. It is in their personal or professional self-interest to advocate for particular policy choices. And they likely believe their preferred policy choice is the right one, the most appropriate one, and the one that should be adopted.

Therefore, institutions, interests, and ideas are to a large degree mutually constitutive – they each interact and reinforce each other to arrive at what the actor believes is the best policy choice, often doing so at the subconscious level. However, it is also useful to try and untangle this process and understand how institutions, interests, and ideas individually shape policy. It is useful to find cases where one of these three elements plays a defining role. With this caveat made, we are going to look specifically at the role of ideas in comparative public policy in this module.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define the five categories of ‘ideas’ as they apply to public policy: cognitive paradigms, normative frameworks, world culture, frames, and programmatic ideas.

- Critically analyze how ‘ideas’ can facilitate or obstruct the public policy process.

- Critically analyze how ‘ideas’ influence the public policy cycle.

- Describe how seemingly dominant policies can appear to suddenly change, with attention to the concepts of the punctuated equilibrium theory and Advocacy Coalition Frameworks.

- Assess the role ‘ideas’ have played in shaping Canadian Foreign Policy.

- Institutions

- Interests

- Ideas

- Cognitive paradigms

- Normative frameworks

- Logic of appropriateness vs. Logic of consequences

- World culture

- Frames

- Anchoring

- Programmatic ideas

- Change

- Adaptive vs. Divergent

- Punctuated equilibrium vs. Incrementalism

- Advocacy

- Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF)

- Same-sex marriage

- Individualism

- Climate mitigation, Climate adaptation

- Imperialism

- Isolationism

- Middle Power

- Multilateralism

- International institutions

- Human security

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

Campbell, John L., “Ideas, Politics and Public Policy,” Annual Review of Sociology 28 (2002): 21-38. [See file in Canvas]

Learning Material

Ideas and Public Policy

Figure 3-5: Canada Pride Flag. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canada_Pride_flag.png#/media/File:Canada_Pride_flag.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Keepscases.

The role of ideas is central to our understanding of public policy, especially regarding policy design and implementation. It should then be no surprise that researchers have paid increasing attention to the role of ideas in policymaking. This research assumes that our appreciation of facts and reality is heavily filtered and mediated by ideas. These ideas are not just individual biases but collective ideational frameworks that help policy analysts, decision makers, and other policy actors make sense of the world. Depending on how deep these ideas are buried and how fundamental they are for our interpretation of the world, they may not even be noticed because they are so assumed as to be taken as a given – taken for granted. But because they are assumptions that only a subset of the population may hold, opposing ideas might animate other groups and result in a clash of the policy process. For example, today in Canada, it is taken as a point of pride that same-sex marriage has been legal since 2005, making it the fourth country in the world to do so after the Netherlands (2001), Belgium (2003), and Spain 3 weeks before Canada on July 3rd. However, until 1948, those practicing homosexuality could be charged with gross indecency. New laws were introduced between 1948 and 1961 that labelled ‘homosexuals’ as criminal sexual psychopaths and dangerous sexual offenders. In 1960, Everett Klippert was interviewed by the police for a non-related event, and when he admitted to the police that he had sex with four men, he was sentenced to three years in prison. The Crown then sought to have him designated a dangerous sexual offender, and the prison psychiatrist subsequently diagnosed him as an ‘incurable homosexual’. He was then sentenced to life in prison. He would finally be released in 1971 after the Government of Pierre Trudeau decriminalized homosexuality in 1969. This shift in policy was facilitated by LGBTQ advocacy and by shifting frames of social mores. It is an example of how public policy can change through a clash of ideas.

How can we use the concept of ideas to explain behaviour? This is no easy task because the term ‘idea’ has multiple meanings, like power or democracy. Yet, regardless of how ideas are defined, as a concept, it represents both a constraint on policymaking and a resource that can be used to encourage policy change. Ideas are, therefore, a constitutive element of public policy. To investigate the role ideas can play in public policy, we will first describe how ideas have been defined. We will then explore theories that incorporate the role of ideas into complete explanations of the policy process. The examination of ideas-based approaches is followed by considering a case study: the broad policy shifts in Canadian foreign policy.

Before moving on, I want you to think of one important ‘idea’ that has changed over time and has shaped contemporary Canadian public policy. For example, think of LGBTQ rights, as introduced above, as such an ‘idea.’

Add your one idea to the Padlet board shown here.

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include the following:

- Your Padlet contribution

- The best Padlet contribution by one of your classmates and why you think this is a strong contribution

What Are Ideas?

Recently, scholars have begun to suggest that policymaking is not always reducible to a simple rational exercise. Or put another way, that policymaking is not just about actors pursuing their narrowly defined self-interest within a set institutional structure. Rather, they have increasingly recognized the role of ideas in shaping beliefs and influencing the process of public policymaking. These ideas have been thought of in a variety of ways. Broadly speaking, ideas can be defined as beliefs, thoughts or opinions. They act as a prism through which we see the world. As such, they help us understand and give meaning to policy problems and help us frame what we believe to be the most appropriate solutions. But things become more difficult when we try to go beyond this broad definition towards something more concrete. Within the public policy literature, we can find a range of approaches that treat ideas as more or less important in the policy process. Some scholars argue ideas are analogous to a world view or ideology, which are so taken for granted that they limit policy debate and subsequent policy decisions. Other scholars see ideas as normative structures which determine broad attitudes to the regulation of behaviour that shapes policy learning and action. This is just a small sample of how ‘ideas’ have been conceptualized. In the narrowest sense, ideas have been used as policy proposals that challenge existing policies and may also represent innovative solutions to policy problems. In the broadest sense, ideas have been used to describe entire systems of beliefs, forms of discourse, and world views.

Figure 3-6: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/idea-fantasia-thought-written-2924175/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of ElisaRiva.

Five Categories of Ideas in Two Broad Influence Types

The work of John Campbell (2002) represents an effort to build a typology of how ideas influence public policy. He identified five categories of ideas in public policy. For our purposes, it is useful to cluster his typology into two broader influence types:

- How ideas constrain public policy making and/or inhibit change. Categories of this type include:

- cognitive paradigms

- normative frameworks

- world culture

- How ideas enable innovative public policy making and/or promote change. Categories of this type include:

- frames (or framing)

- programmatic ideas

1. Constraining and/or Inhibiting Change

Let us look first at how ideas can constrain public policy. Cognitive paradigms are those deeply internalized beliefs that shape how policymakers see the world, see an issue, or how they understand the mechanics of a policy. For example, there is a deep attachment to individualism in the US, which sharply constrains policy options on issues like health care or gun control. While other similarly developed states may strictly prohibit or put significant obstacles to gun ownership, such debates have failed to gain political traction in the American legislative system.

Figure 3-7: President George W. Bush delivers his State of the Union address to a joint session of the United States Congress on 28 January 2003. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:G.W._Bush_delivers_State_of_the_Union_Address.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Susan Sterner.

Normative frameworks are similar to cognitive paradigms in that they are deeply internalized. However, instead of shaping agents’ beliefs, they shape and are in turn shaped by a person/communities’ values, identities, and roles – in other words, they shape beliefs about what ‘should be’. In so doing, normative ideas limit what is deemed to be acceptable policy options. From this perspective, policymakers are acting on what March and Olsen call a ‘logic of appropriateness’ – acting based on what is expected of you in the role that you inhabit. This stands in contrast to the ‘logic of consequences’ – acting on a strict snapshot of your narrowly defined self-interest. For example, compare the policies of the BC NDP government of Horgan and the AB NDP government of Notley. These are two governments holding office at roughly the same time and from the same, or at least similar, political ideology. Yet, these two NDP governments are decidedly different, making different policy choices that are at times even hostile to one another. They fought over the Trans Mountain Pipeline, refused to honour the tradition of supporting each other’s campaigns, and even briefly resulted in Alberta banning BC wine. Some of this can convincingly be explained by the different expectations of appropriate behaviour for the Premier of BC and the Premier of AB based on normative expectations.

Figure 3-8: Digitally altered images of John Horgan and Rachel Notley from Government of BC and Government of Alberta. Source: https://thetyee.ca/Opinion/2018/04/13/Please-Advise-NDP-Buddies-Get-Along/ Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

World culture represents a broader category of how ideas can shape and constrain public policy. World culture encourages policymakers to align with dominant systemic values. For example, many of the contemporary international economic and political structures are based on the values and interests of Western states. For example, the very basis of the contemporary sovereign state system is rooted in the values and norms of European history. The liberal international economic order is based on European economic theory. Further, both the sovereign state system and the liberal international economic order were globalized through European powers’ imperial and colonial practices. The rest of the world, and perhaps most significantly, the newly decolonized states, have largely adopted these Western values as part of the contemporary world culture. This has influenced everything from the sovereign state system and the neo-liberal international economic order to the form and function of international development and democracy promotion in developing states.

Figure 3-9: Flags of the United Nations. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:United_Nations_Flags_-_cropped.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Tom Page.

From cognitive paradigms to world culture, these approaches demonstrate how ideas or ideational structures constrain policymaking.

2. Enabling and/or Promoting Change

The second broad influence type is how ideas enable public policy making and/or promote change. Change is always difficult and always comes with risk, both in terms of achieving policy objectives and of possible political costs. The risk to policy objectives lies in the unknown – it is impossible, or at least very difficult, to predict how new policies will work, what new issues they may generate, and how people will respond. The political risk lies with the challenge that policy change has for vested interests: change invariably creates winners and losers. Change may also threaten local identities or values. This is why policymakers tend towards policies that resonate with past practices, national traditions, and social norms. However, sometimes change is necessary because of changing material or ideational circumstances. If policymakers do depart from standard practices and embark on a new policy trajectory, they need to mitigate the risks involved.

Framing is one means to mitigate this risk by making policy politically acceptable. Policymakers do this by anchoring policy in historical narratives or linking policy to generally accepted norms, values, and beliefs. For example, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Canada’s military role in the world was unravelling. Despite a broad public identification of Canada as a liberal internationalist state, and more specifically, a peacekeeping state, Canada’s contribution to both had been in sharp decline. A degree of dissonance had been forming between how Canadians saw themselves in the world and how Canada acted in the world. In 2006, the Harper Government began to shift Canada’s defence policy away from liberal internationalism and peacekeeping to a more muscular military role that sees Canada as a moral defender of liberal values. Canadian operations as part of the NATO mission in Afghanistan is a good example of this shift. To legitimate and reconcile this new world view with the Canadian identity, the Harper Government sought to connect this muscular military role with the past: The War of 1812, the two World Wars, and the Cold War. He was framing his defence policy as true to Canadian values and, in the process, sought to delegitimize the liberal internationalism that had dominated foreign policy since World War II. While framing can explain how new ideas may be brought into the policy-making process, it does not explain which new ideas may be brought in or why.

Figure 3-10:Canadian Forces in Kandahar Province, Afghanistan. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LAV3patrol.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of ISAF Headquarters Public Affairs Office from Kabul, Afghanistan.

The role of programmatic ideas can provide some answers to these ‘how and why’ questions. Programmatic ideas help actors to develop concrete solutions to their policy problems. These can be technical or professional ideas that specify cause and effect relationships and prescribe a precise course of policy action. Such ideas are often presented in policy briefs and position papers to policymakers and, if convincing, are consciously and deliberately applied. For example, in the 2007-08 global financial crisis, the largest states in the world faced a systemic threat to the international economic order. Governments confronted a massive liquidity crisis, the threat of major corporations and financial institutions becoming insolvent, a likely reduction in international trade, a surge of unemployment… essentially conditions that were perceived to be setting the stage for a crisis on par with the Great Depression of the 1930s. Upon the advice of advisors in government and from their central banks, governments around the world, including Canada, introduced unprecedented stimulus packages with the hope of averting or at least blunting the worst outcomes of the crisis.

Programmatic ideas can also be part of political platforms that form key points of contention between political parties, especially during elections. For some parties, like the Green Party or the New Democratic Party, these programmatic elements remain fairly consistent over time: environmentalism for the Green Party and socially progressive policy for the NDP. However, for other parties, programmatic ideas are more localized to specific periods or specific elections. For example, the Liberal Party of Canada and iterations of the current Conservative Party of Canada have historically traded positions over time on issues like free trade or provincial autonomy. Yet, they can and do bring certain ideas with them into office if elected. In 2014, the Government of Justin Trudeau campaigned heavily on environmental policy and has since entered into a contentious fight with Conservative provinces overapplying a tax on carbon.

Figure 3-11: Canadian Minister for the Environment and Climate Change Catherine McKenna (Far Right) at Paris Climate Summit. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/worldbank/26429598345/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of World Bank Photo Collection.

Both framing and programmatic ideas enable innovative policy making and/or policy change.

First, watch John Butman’s Big Think video ‘How to Succeed as an Idea Entrepreneur’: https://youtu.be/8RX_pdlXQJQ

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- What is an Idea Entrepreneur?

- What is the goal of Idea Entrepreneurs?

- How does an Idea Entrepreneur seek to shape public policy?

- Why does Butman argue it is important to connect ideas to other ideas?

- How can we apply the insight of Butman’s Idea Entrepreneur concept to public policy?

Ideas in Comparative Public Policy

Ideas in the Stages of the Public Policy Cycle

In order to highlight the means by which ideas influence policymaking, it is useful to first go back to the heuristic of the policy cycle introduced in Module 1. This simplifying device moves policy through five stages: agenda setting, policy formulation, decision making, implementation, and evaluation. Ideas are perhaps most significant in the first stage, agenda setting. As a reminder, in the agenda setting stage, actors seek to have an issue put before authoritative decision makers because they believe it to be important for themselves or the entire body politic. Most issues first appear on the public or systemic agenda. If the issue starts to gain traction in the wider body politic or generates enough noise to get the attention of the media or government decision makers, it may move to the institutional agenda – the list of those issues that the government formally recognizes. Alternatively, an issue may start on the institutional agenda if it is an issue the government itself believes to be important.

Figure 3-12: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/silhouettes-person-human-man-woman-776667/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Either way, what is significant for us in this module is that agenda setting is essentially a process of contestation. People, whether they be in government or the wider body politic, are advocating on behalf of an issue because they believe there is a problem or opportunity that needs to be addressed.To address such problems or opportunities, they are advocating for change. The proposed change can be adaptive or incremental, tinkering with existing policies, or they may be divergent, advocating for large-scale changes to the status quo. In debating whether to adapt or diverge from existing policies, ideas will play an important role in two ways:

- First, in trying to get issues on the institutional agenda, actors are competing with other actors with other ideas for limited space.

- Second, the change will be resisted by those cognitive paradigms that define how decision makers see the world; by those normative ideas that shape decision maker’s values, identities, and sense of role; by the wider world culture that establishes systemic values. The larger the change proposed, the more virulently defenders of the status quo will oppose it. This makes it more difficult to gain traction in the public or systemic agenda and even more difficult to make it onto the institutional agenda.

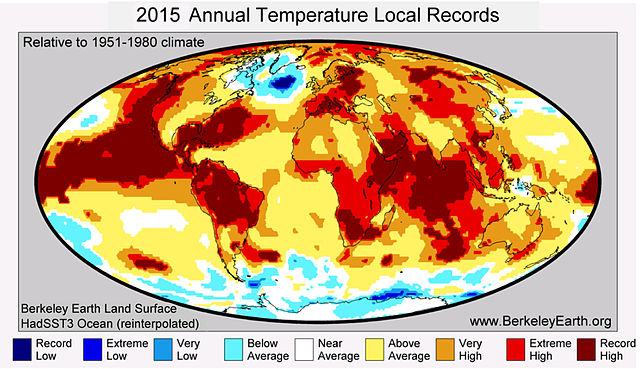

Take climate change, for example. There is a strong consensus in the scientific community that climate change is being driven by human behaviour. Further, there is a strong consensus that all of humanity will be deeply and negatively affected without radical change. The scientists and policy experts have been putting forward programmatic ideas to address climate change since at least 1979, when the First World Climate Conference was convened. Now, we are past the point of ‘stopping’ climate change.

Figure 3-13: 2015 Annual Temperature Local Records. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2015_Annual_Temperature_Local_Records.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Berkeley Earth.

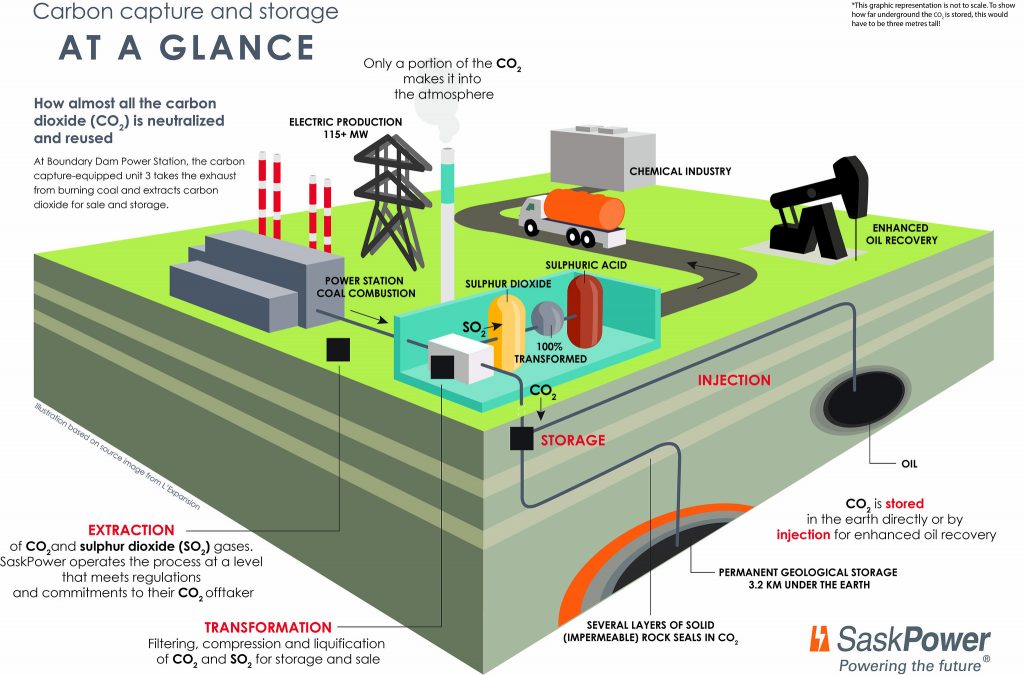

Rather, ideas for climate mitigation and climate adaptation are on the systemic agenda. In many countries, Canada included, these ideas have made it onto the institutional agenda of governments. But they have not done so unscathed. For the most part, what emerges in climate/environmental policy is much weaker than what was proposed. Many in the scientific community argue what emerges is fully inadequate. Why? The changes advocated for by the scientific community would completely transform our global politics and the global economy. And this is a threat to many vested interests and would require an incredible transformation of our political and economic institutions. Actors push back with alternate ideas that either seek to discredit the scientific consensus or propose less transformative and more adaptive policies. An example of an alternate idea is the Carbon Capture plant in Saskatchewan. At its heart, this is a contestation of ideas.

Figure 3-14: Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) at a glance. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/saskpower/20797776173/ Permission: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Courtesy of SaskPower.

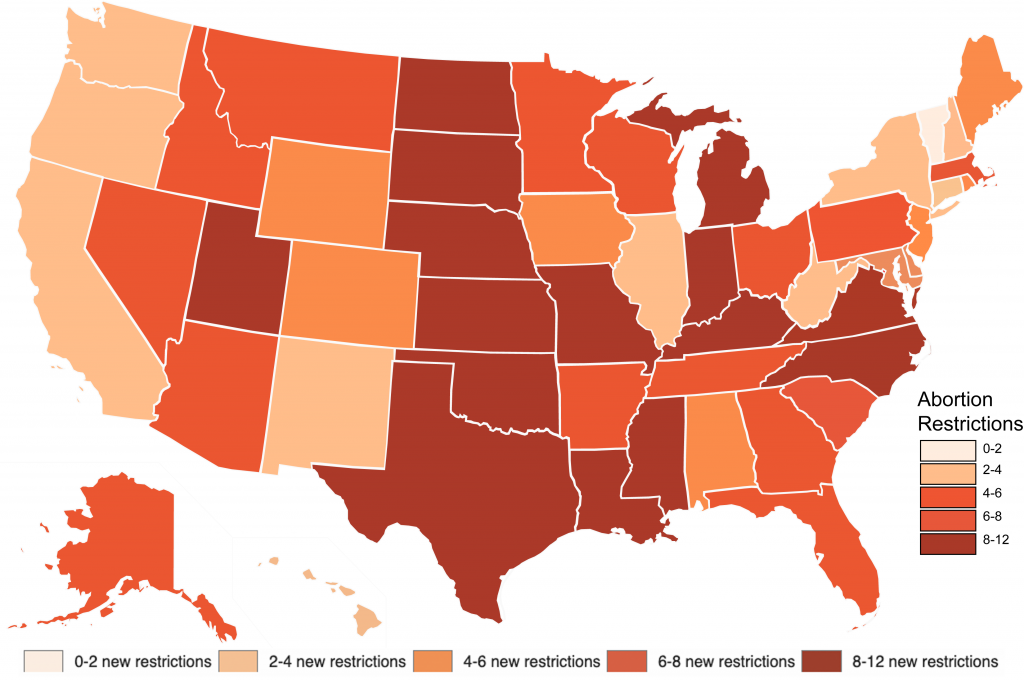

Ideas also play an important role in the decision-making stage. Decision makers, like all actors, see the world through cognitive paradigms and normative ideas. These are internalized aspects of how decision makers see the world and see their role in it. When decision makers have to decide which policy option, if any, to pursue, these ideational components will play a role. At times, this may be a wholly conscious decision. For example, at the provincial and federal level, decision makers will often view policy choices through their party platforms. It makes sense that these party platforms resonate with their world views since they opted to join and run as a candidate in that party. A decision maker associated with a party aligned with business interests may opt for policies that minimize government bureaucracy. A decision maker associated with a party aligned with labour interests may opt for policies that support the industry’s tougher and more intrusive government regulation. Or perhaps even more poignantly, in 2019, there has been a strong push for anti-abortion legislation in the US driven by a normative argument that abortion is immoral. This argument is not new. But given the support of the Trump Presidency and his appointment of two Supreme Court Justices, many social conservatives and predominantly Republican decision makers believe an opportunity exists to challenge the legal basis of abortion – Roe v. Wade. Bills that seek to procedurally restrict abortions after six-weeks of conception, in practice largely banning abortion, have passed, or are before their respective state legislatures, in nine US and Republican-led states: Louisiana, Missouri, South Carolina, Tennessee, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Texas, and West Virginia. In May of 2019, Alabama has gone further and passed a law that makes abortion illegal and threatens doctors who perform the procedures with 99-year jail terms. Whether you are pro-life or pro-choice, this is not a debate on scientific principle or rational policy decision making – it is a normative debate that is deeply influenced by the decision makers’ worldview.

Figure 3-15: Abortion restrictions in the USA (2013). Permission: Courtesy of course author Martin Gaal, PhD Lecturer, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan, based on https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AbortionRestrictions2013.svg

Beyond the agenda setting and decision-making stages, ideas play a lesser but still significant role in the other stages of the policy cycle. In the policy formulation stage, government bureaucrats are tasked with reaching out to stakeholders and establishing a set of options for the government to consider if the policy debate is to move forward. At this stage, we expect programmatic ideas via policy options that will causally address the issue as identified. Yet, even at this more technical stage, it is difficult to remove these bureaucrats’ cognitive paradigms and normative ideas. A similar tension exists in the policy implementation stage. For example, frontline civil servants may exercise agency in translating how policies are put into practice. And again, in the policy evaluation stage, ideas play a role when establishing the criteria by which policies will be evaluated.

Ideas and Times of Change

This discussion on the role of ideas in the policy cycle has highlighted a very important point – the role of ideas is most identifiable at points of change and, more specifically, at moments of transformational change. At such pivotal moments, we can distinguish, or at least glimpse, the causal role that ideas play in public policy – even as they coexist in that mutually constitutive relationship with interests and institutions. Some public policy scholars have employed metaphors to describe ideas as viruses infecting political systems or as irresistible forces sweeping all obstacles aside to cause profound change. Of particular interest is where new ideas come from, how they are contested, and when and why some ideas prevail over others. From this, a few things have been identified as important. First, the status quo is almost always in a privileged position. For new ideas and new policies to replace the status quo, they must overcome significant obstacles. This has led Baumgartner and Jones to apply the evolutionary biology principle of punctuated equilibrium to public policy: a model where public policies are stable for long periods of time until punctuated by critical events that lead to radical change. This stands in contrast to incrementalism, where policies change more slowly, in an almost evolutionary mode. An example of the punctuated equilibrium model is the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the US in 1970 in response to shocking environmental tragedies like the dramatic image of the Cuyahoga River on fire. Another example is the creation of the United Nations (UN) in response to the most tragic and destructive conflict in history, World War II, and the inhumanity of the Nazi regime. In both the EPA and the UN, some shock destabilized the status quo and created the opportunity for new ideas and policies to become established.

Figure 3-16: 1969 Cuyahoga River Fire. Source: https://flic.kr/p/p7Wi7U Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of USEPA Environmental-Protection-Agency. |

Figure 3-17: UN symbol. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emblem_of_the_United_Nations.svg#/media/File:Emblem_of_the_United_Nations.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Spiff~enwiki. |

However, many other scholars have noted that the Baumgartner and Jones model suggests that these critical events appear unexpectedly or almost randomly when in reality, these critical events are often the result of long processes and, perhaps more importantly, intense advocacy. In the case of the EPA, the roots of global environmentalism can be traced back to the Romanticism movement in the 19th century, early advocacy networks like the Sierra Club, and scientific communities that were institutionalized through organizations like the League of Nations and the UN. In the 1960s, the environmental movement in the US had been mobilized by several large advocacy groups and had gone mainstream in response to Rachel Carson’s book ‘Silent Spring’. Carson’s book detailed how pesticides weres threatening both the environment more generally and human health more specifically. All of this created a movement that called for a regulatory body to protect the environment, and was triggered into action by the image of the Cuyahoga River fire. On the other hand, the UN resulted from high diplomacy between the Allied powers at the end of World War I and the more informal advocacy of individuals and groups seeking to establish global institutions dedicated to world peace. Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith created the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) theory to capture this’ behind the scenes’ work. According to the ACF approach, people engage in politics to turn their beliefs and ideas into policy. They form advocacy coalitions with people who share their beliefs and then engage in the process of competition with other coalitions. All of this takes place within a subsystem devoted to a particular policy issue, within a wider policymaking process, and within a context that provides constraints and opportunities to coalitions. Again, we see the mutually constitutive nature of the policy making process, with ideas, interests, and institutions all playing a part. But for the purposes of this module, these coalitions are driven by the belief that their ideas, on the issue they care about, is right, good, and appropriate. And this belief drives policy contestation and, if successful, change.

Figure 3-18: Idle No More protest, Ottawa, 2013. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Idle_No_More_2013_Ottawa_1.jpg Permission: CC By-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Moxy.

The Comparative Role of Ideas in Public Policy

Finally, we need to address the comparative role of ideas in public policy. First, we can see that there is a comparative element in the very nature of ideational contestation. Policy change is driven by one idea and/or policy being promoted as better than an existing policy that is potentially based on a different idea. In analyzing which policy is better, there is by necessity some degree of comparison happening. Advocacy groups, bureaucrats, decision makers, and evaluators, for example, will all have to do some comparative work in deciding whether the proposed policy is better than the existing policy; whether the proposed policy will accomplish its stated goals; whether those stated goals are worth pursuing.

Second, in seeking to find solutions to policy opportunities and threats, actors will look at what other actors are doing. They will look at other polities that share similar defining features to see if they have enacted policies to address similar issues. For example, the City of Toronto may look to how the City of Vancouver deals with the issue of real estate being used for foreign money laundering and vice versa. Or if the Canadian government decides to pursue a national pharma care plan, they may look to other states that have enacted such policies, likely northern European states.

Figure 3-19: “Money laundering.” Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/money-laundering-crime-fighting-1963184/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of stevepb.

Advocacy groups may also look to dissenting voices in other polities to see how they have countered dominant policy narratives. If they find a counter-narrative that has proven successful, they may import those ideas into their own struggle. For example, the movements for universal suffrage, women’s rights, Indigenous rights, labour rights, and gun control activists, to name just a few, have all shared ideas and strategies across borders. In sum, ideas are not only an essential part of understanding public policy, but they also play an important role in the comparative aspect of public policy.

Figure 3-20: Near the Trump International Hotel (frame right), two young girls protest at the March For Our Lives rally in Washington, D.C. Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/_ANxZIWTHdA Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Tim Mudd on Unsplash (https://unsplash.com/license).

First, watch “Punctuated Equilibrium: An Introduction”: https://youtu.be/jX2ecS7ri2I

Next, read the article from BBC News, “US gun laws: why it won’t follow New Zealand’s lead” by Anthony Zurcher: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-41489552

*Note: keep this video and its main ideas in mind when you reach Module Six, as the theory of punctuated equilibrium is applicable to the Mulitple Streams Approach and more specifically the idea of a Policy Window.

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- What is punctuated equilibrium in public policy?

- Why are certain policies stable over long periods of time?

- Why do policies, or policy images, suddenly change?

- Apply the concept of Punctuated Equilibrium to gun control:

a. Why and how did gun control change in New Zealand?

b. Why does the article argue the US is unlikely to change its gun laws even with much higher levels of gun violence?

c. What kind of critical event, if any, do you think it would take for radical gun control to succeed in the US?

Case Study: Canadian Foreign Policy Seen Through an Ideational Lens

The Shift from Isolationism to Middle Power Internationalism

Canadian Foreign Policy offers an interesting case study into the role ideas play in comparative public policy. The history of Canadian Foreign Policy is relatively short compared to other states, like France, the UK, India, or China. Yet, there are sharp distinctions between different phases of Canadian Foreign Policy between confederation and now. These shifts in foreign policy orientation are deeply influenced by ideational factors, by identity, by changing beliefs regarding Canada’s place in the world. This section will look at a specific change in Canadian Foreign Policy orientation that occurred at the end of World War II.

But first, a bit of context. Between 1867 and 1945, Canadian Foreign Policy was dominated by the logics of imperialism and isolationism. While the Canadian state had achieved independence in 1867, this independence was limited to its domestic affairs. Until World War I, Canada was completely dependent on the UK, in essence Canada was an imperial appendage of the UK.

Figure 3-21: The territories that were at one time or another part of the British Empire. The United Kingdom and its accompanying British Overseas Territories are underlined in red. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_British_Empire.png#/media/File:The_British_Empire.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of The Red Hat of Pat Ferrick.

From the end of World War I in 1919 through the inter-war years, Canadian Foreign Policymakers were beginning to push against British paternalism. They sought to defend Canadian interests, and they believed that isolationism was the best way to do that. In 1931, the white British Dominions, including Canada, gained control of their foreign policy through the Treaty of Westminster. For the first time, Canada was free to formulate its own foreign policy orientation. The two most important determinants that preoccupied decision makers at that time was the declining influence of the British and the rising influence of the Americans. While Canada had begun to push back against British control, they were also wary of being entirely without protection. The Americans, on the other hand, had been a potential military and economic threat to Canada since the American Revolution. A more powerful and influential American state was therefore deeply concerning to Canadians. In response, Canadian policymakers tried to chart a path that was independent of both powers, adopting an isolationist foreign policy.

Figure 3-22: Douglas Coupland’s ‘Monument to the War of 1812’ (2008) in Toronto; depicts a larger-than-life Canadian soldier triumphing over an American. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Couplandart.jpg#/media/File:Couplandart.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of HBW 40.

These policymakers believed that Canada was a small and insignificant state whose interests were best served by largely staying out of international affairs. This isolationist policy orientation was dominant until World War II. However, following the war, Canadian policymakers emerged as dedicated liberal internationalists. It is this dramatic shift in foreign policy orientation that we are going to focus on in this section.

In order to highlight how dramatic this shift in foreign policy orientation was, it is useful to contrast two quotes by Canadian officials. During the interwar years, Loring Christie, a Canadian official in the Department of External Affairs argued:

Compare Christie’s statement with that of another Canadian civil servant, Walter Riddell. He argued in 1949 that countries such as Canada…

Riddell’s statement describes Canada as a Middle Power. Middle Powers are those states with middling resources that have adopted a liberal internationalist foreign policy: supporting multilateralism, dedicating resources to international institutions, seeking to mitigate international conflict, and taking leadership roles in human security initiatives. For example, Canada played an important role in the creation of modern peacekeeping, the success of the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa, the signing of the Anti-personnel Landmine Ban, the formation of the International Criminal Court, and the establishment of the Responsibility to Protect. It is important to note, that the Middle Power concept is not uncontested. For example, some scholars question the degree to which Canada was able to exert meaningful influence in global affairs. But it is not contested that the idea of Middle Power internationalism was a dominant paradigm that deeply influenced how Canadians, and in particular Canadian decision makers, saw Canada’s role in the world. And this, in turn, proscribed what behaviour was appropriate given this Middle Power role. So how do we explain this dramatic shift in Canada’s foreign policy orientation?

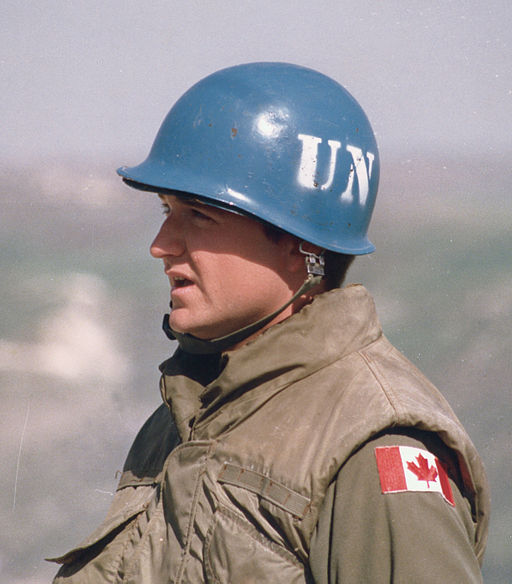

Figure 3-23: A Canadian soldier of the United Nations Peacekeepers. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:UN-Marty.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of HoCComms.

The Role of Ideas in this Shift

There are three ways that ‘ideas’ facilitated this shift from isolationism towards Middle Power internationalism.

First, the two World Wars, but most importantly World War II, fundamentally shifted the cognitive paradigm of Canadians vis-à-vis the role of Canada. Several aspects explain this shift. First, Canada had been drawn into a World War, a total war, not once but twice in the space of thirty years. These were horrific events with catastrophic consequences for the countries involved, both materially and in the human cost of those who fought and were injured or killed. Ten percent of the Canadian population served in World War II, nearly 44,000 servicemen were killed, and another 55,000 were wounded in the process. These were conflicts that were driven by the hubris and ambitions of the world’s Great Powers. Yet in participating as ‘Canadian’ troops, in making instrumental contributions in particular battles like Juno Beach on D-Day, in playing a comprehensive role across the global theaters of war, even in the civilian role back home of producing the armaments and food for the war effort – Canada and Canadians were enacting agency. They were no longer the small, unimportant state that Christie described. Rather, when the war was over, Canada represented Riddell’s description of Canada as nearing the Great Powers – Canada had the fourth largest air force, one of the largest navies, and a significant army. In essence, Canada emerged a much different actor from World War II – it was more powerful than it had ever been, it had played a significant role in global affairs, and Canadians increasingly believed international relations could no longer be left to the Great Powers. Canada had become a country too big to avoid international conflict but too small to play a determinative role in the outcome of such conflict.

Figure 3-24: Canadian soldiers landing at Juno Beach in France during the Invasion of Normandy, June 6 1944. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canadian_landings_at_Juno_Beach.jpg#/media/File:Canadian_landings_at_Juno_Beach.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

The cognitive paradigm through which Canadian policymakers saw the world and Canada’s role in it had shifted. Canada was no longer a small, unimportant state but rather a Middle Power state able to contribute to global issues. Their perspective shifted from believing the Great Powers should govern the world to a worldview where multilateral governance was paramount. They no longer believed Canada could count on its geographic isolation for protection and instead argued Canada needed to seek its security and prosperity through active engagement.

Second, World War II challenged the dominant ideas of how the world worked and how the world should work. The creation of the United Nations and other institutions of global governance challenged the prerogatives of the Great Powers. The use of force to achieve a state’s interests was deemed illegal and to do so would remove a state from being an upstanding member of the international community. While much of this would fail to materialize in practice, especially with the onset of the Cold War, in 1945 these sentiments were the dominant ideas in the world culture. It was the era of global governance, an era where the upstanding members of the international community had the opportunity to rid the world of the scourge of war. This emerging world culture provides a language and a platform for states like Canada to envisage a liberal internationalist foreign policy orientation that could secure their security and prosperity. The idea underpinning global governance facilitated and legitimated their new Middle Power role.

Third, as Canadian policymakers adopted and began to practice a Middle Power foreign policy, they began to internalize the role. As the Middle Power role was internalized, the Canadian public and Canadian policymakers began to develop normative ideas of what Canadian Foreign Policy should be. This is able to explain how Canadian Foreign Policy went from supporting the UN in 1945 to taking on a significant leadership role in the field of human security in the 1990s. In the first case, it is easy to reconcile supporting the UN as being in Canada’s narrowly defined self-interest. This may have in-and-of itself been a radical shift from Canada’s past isolationist tendencies, but it is easily explainable as it was deemed the best way to achieve peace and prosperity. It is more difficult to explain the decision to expend significant material and political capital to promote human security: The International Criminal Court, the Anti-personnel Landmine ban, the Responsibility to Protect. These initiatives provided Canada with little direct benefit. In fact, they were mostly other-orientated versus self-interested and came with significant costs. However, if viewed through a normative lens, this makes more sense. As Canadian policymakers began to enact the Middle Power role, a narrative coalesced around Canada as a good international citizen. It became axiomatic that Canada should support multilateralism, conflict resolution, and human rights. It was such normative ideas that shaped, or at least influenced, Canada’s foreign policy decision making. With that being said, the normative expectations of Canada as a Middle Power have weakened considerably since the early 2000s. This has generated a new round of dissonance in paradigms around Canada’s place in the world.

Figure 3-25: Peacekeeping Memorial in Ottawa. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Peacekeeping_Memorial_Ottawa.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Ken Banks.

Watch “United at War: Canada, the Story of Us Ep.8”: https://youtu.be/HDwPMPczwvc

*Note: this is a very idealized narrative of Canada in World War II. This is intentional. Often cognitive paradigms and normative ideas have been crafted and distilled over time. It is these crafted narratives that harden the ideas of what actors ‘should’ do. With that being said, it is also important for us to be critical of these narratives – so take the video for what it is.

*Note: If you found this video interesting, there are ten episodes in the series and all are available on YouTube.

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How did the efforts of Canadians at home contribute to the war effort?

- How did the efforts of Canadian scientists contribute to the war effort?

- How did the efforts of Canadians contribute to the French resistance?

- How did the efforts of Canadians contribute to fighting the war? Make a specific note of the D-Day invasion.

- What was the cost to the Canadian contribution to the war effort?

- How do you think World War II changed how Canadians saw themselves and their place in the world?

- How do you think this changed the cognitive paradigms that have influenced Canadian Foreign Policy?

- Are these cognitive paradigms still at work today?

Conclusion

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the concept of the role that ‘ideas’ play in the public policy process. We began by recognizing the caveat that it is very difficult, if not dishonest, to argue that ideas alone determine outcomes. In practice, outcomes are often a result of the complex interaction between ideas, interests, and institutions. However, even with that being said, it is useful to look for cases where each element has played an interesting role in order to understand the causal impact of each.

We then turned to the work of John Campbell, who has identified and expanded on five ideational logics: cognitive paradigms, normative frameworks, world culture, frames, and programmatic ideas. We clustered the first three logics, cognitive paradigms, normative ideas, and world culture, into a group that tends to inhibit or constrain policy change. We clustered the last two logics, frames and programmatic ideas, into a group that tends to facilitate or legitimate change.

Next, we moved onto the role ‘ideas’ play in the comparative part of public policy analysis. We noted that if we look at the role of ideas through the heuristic of the policy cycle, we can see that ideas play a particularly important role in the agenda setting and decision-making stages. In the agenda setting stage, new ideas are seeking to challenge existing ideas to adapt or wholly replace the existing policy. However, we also noted that we could see the role of the ideas in the way they shape what bureaucrats, civil servants, and policy evaluators believe to be good, right, or appropriate policy choices and outcomes.

By looking at the interaction of ideas in the policy cycle, we see that the role of ideas is most noticeable at points of change. Baumgartner and Jones proposed the punctuated equilibrium theory to explain both the longevity of particular policies and sudden policy changes. This is a solid theory that attempts to make sense of how seemingly dominant policies can suddenly be replaced. Other theorists have looked at how new policies coalesce to challenge existing policies. For example, we looked at how Advocacy Coalition Frameworks bring together people working to advance such policy alternatives.

We concluded with the case study of Canadian Foreign Policy change following World War II. In so doing, we are able to see the role that cognitive paradigms, world culture, and normative ideas all deeply impacted Canadian Foreign Policy. Canadian action during the war changed how Canadian policy makers saw the world and saw Canada’s role in the world – it changed Canada’s cognitive paradigm. The creation of the UN and other institutions of global governance deeply shaped the norms of emerging world culture – war was made illegal, and trade would be managed. This provided a platform for Middle Power internationalism. Finally, as Canadian policymakers increasingly engaged in Middle Power internationalism, sometimes more rhetorically than in practice, they internalized the role, generating normative ideas about what a Middle Power should do; about what is appropriate for a Middle Power state in particular contexts.

In the next two modules, we will be looking at the role of interests and institutions in shaping public policy. However, as we do this, it will be useful to reflect back on the caveat made at the beginning of this module – ideas, interests, and institutions are all involved in the policy making process. Therefore, the role of ideas that we discussed in this module will also be at play in discussing interests and institutions.

Review Questions and Answers

Campbell identified cognitive paradigms, normative frameworks, and world culture as ideational concepts that influence public policy making:

- Cognitive paradigms are those deeply internalized beliefs that shape how policymakers see the world, see an issue, or how they understand the mechanics of a policy.

- Normative ideas shape and are, in turn shaped by a person/communities’ values, identities, and roles – in other words, they shape beliefs about what ‘should be’.

- World culture encourages policymakers to align with dominant systemic values.

All three ideational concepts reinforce the status quo in public policy. All three are internalized into how actors see the world, see themselves, and see what the appropriate action is in any given situation.

Campbell identified frames and programmatic ideas as ideational concepts that influence public policy making:

- Frames are used by politicians to legitimate policy change. Frames do this by anchoring policy in historical narratives or linking policy to generally accepted norms, values, and beliefs.

- Programmatic ideas help actors to develop concrete solutions to their policy problems. These can be technical or professional ideas that specify cause and effect relationships and prescribe a precise course of policy action. Programmatic ideas can also be part of political platforms that form key points of contention between political parties, especially during elections.

Both frames and programmatic ideas enable stakeholders and most specifically decision-makers to adopt and implement new policies. Framing seeks to embed new policy within existing norms and beliefs or even to argue that this new policy better represents an actor’s identity or belief system than the existing policy. When programmatic ideas offer solutions to policy problems or opportunities, they are suggesting a change to the status quo, either for functional reasons or for ideological ones. Both frames and programmatic ideas facilitate change in public policy.

If we look at the role of ideas through the heuristic of the policy cycle, we can see that ideas play a particularly important role in the agenda setting and decision-making stages. In the agenda setting stage, new ideas are seeking to challenge existing ideas to adapt or wholly replace the existing policy. Ideas are also important in the decision-making stage. Decision-makers see the world through those cognitive paradigms and normative ideas that they consciously and subconsciously hold. These ideational concepts act as a prism by which they see the world and see their role in the world. This, in turn, shapes what they believe to be the appropriate action to take in any given circumstance.

While ideas most clearly play a role in agenda setting and decision making, you can also see the influence of ideas in other stages. In the policy formulation stage, implementation stage, and evaluation stage, what the actors believe to be good, right, and appropriate will influence how they undertake their respective roles.

Punctuated equilibrium theory is a model created by Baumgartner and Jones where public policies are stable for long periods of time until punctuated by critical events which lead to radical change. This helps to explain why seemingly stable policy frameworks can remain in place for long periods of time and then suddenly be replaced by new policy frameworks. For example, we introduced two examples, the creation of the EPA and the creation of the UN as drastic policy changes.

However, this leaves our understanding of public policy change a bit underdeveloped. The question remains, where do these new policy frameworks come from? Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith created the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) theory to answer this question. According to the ACF approach, people engage in politics to turn their beliefs and ideas into policy. They form advocacy coalitions with people who share their beliefs and then engage in a process of competition with other coalitions. All of this takes place within a subsystem devoted to a particular policy issue, within a wider policymaking process, and within a context that provides constraints and opportunities to coalitions.

Together, these two theories attempt to explain how and why policy changes.

The role of ideas is most identifiable at points of change and more specifically at moments of transformational change. It is at such pivotal moments that we are able to distinguish, or at least glimpse, the causal role that ideas play in public policy – even as they coexist in that mutually constitutive relationship with interests and institutions. At moments of transformative change, ideas are in sharp contrast. New ideas are opposing both the status quo and alternate ideas which may be less transformative. Moreover, such points are fundamentally comparative. New ideas are being compared to existing ideas. New ideas are sought from new places to address new policy opportunities and threats.

Glossary

Adaptive: refers to policy change that is incremental and seeks to shift policy orientation by tinkering with existing policy frameworks.

Advocacy: engaging in the active promotion of particular policies or policy options, with the intent of convincing policymakers and/or the general public as to why particular policy options are better than competing ones.

Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF): describes a process in which people engage in politics to turn their beliefs and ideas into policy by forming advocacy coalitions with people who share their beliefs and then engage in a process of competition with other coalitions.

Anchoring: the process that links policy to generally accepted norms, values, beliefs, and historical contexts with the intent of legitimating particular policy options.

Change: in policymaking are those points where the status quo is replaced with new policies/policy orientations that are either adaptive or divergent in nature.

Climate adaptation: refers to the shift in international environmental policy from trying to stop or to lessen the impact of climate change, to policies that accepts there is, or will be, new climate realities.

Climate mitigation: refers to policies that seek to lessen the impact of climate change on human populations.

Cognitive paradigms: deeply internalized beliefs that shape how policymakers see the world, see an issue, or how they understand the mechanics of a policy.

Divergent: advocating for large scale, transformative change to existing policy or policy frameworks.

Frames: cognitive structures used to shape the way people think of something and often to legitimate new policy choices.

Human security: represents a shift from traditional security studies where borders and state interests are predominant to human beings as the referent of security. This can be minimal in the form of security from gross human rights abuses to more comprehensive by including security in human needs: shelter, food, employment, political participation.

Ideas: in policymaking can be both conscious and sub-conscious frames which shape beliefs and subsequently constrain or facilitate the progress of new policy solutions.

Imperialism: a policy of extending a country's power and influence through diplomacy or military force.

Incrementalism: refers to policy change that moves slowly, in an almost evolutionary way, to shift policy form or function.

Individualism: the idea that freedom of thought and action for each person is the most important quality of a society, rather than shared effort and responsibility.

Institutions: both formal organizations and the informal patterns of rules, norms, and practices that shape the behaviour of actors.

Interests: a wide range of forces which create contextual frames that motivate both individuals and organizations to be deliberate and act in particular ways.

International institutions: can be formal organizations with a permanent standing body or informal sets of related constitutive, regulative, and procedural norms and rules that pertain to the international system.

Isolationism: is a policy of remaining apart from the affairs or interests of other groups, especially the political affairs of other countries.

Logic of appropriateness: refers to the decision making process whereby actions are based on expectations of actors in the role that they inhabit.

Logic of consequences: refers to the decision making process whereby actions are based on a snapshot of your narrowly defined self-interest.

Middle Power: a state with middling resources that has adopted a liberal internationalist foreign policy.

Multilateralism: more narrowly defined, refers to the participation of three or more parties seeking to address an issue, and more broadly defined, refers to a normative argument that international issues should be addressed by broad coalitions of interested actors.

Normative frameworks: deeply internalized ideas that shape, and are in turn shaped by, a person/communities’ values, identities, and roles, which in turn shape beliefs about what ‘should be’.

Programmatic: in policy making refers to either policy proposals by experts to address technical problems or policy proposals that are tightly embedded in ideological or partisan beliefs.

Punctuated equilibrium: a policy model where public policies are stable for long periods of time until punctuated by critical events which lead to radical change.

Same-sex marriage: marriage between partners of the same sex.

World culture: constituted by the ideas and beliefs of dominant actors in a particular system which in turn punishes or rewards others who act or do not act upon them.

References

Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones. 1991. “Agenda Dynamics and Policy Subsystems,” Journal of Politics 53:1044–1074.

Béland, Daniel. "Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Change." Journal of European Public Policy 16, 5 (2009): 701-18.

Blakemore, Erin. “The Shocking River Fire That Fueled the Creation of the EPA.” History

Channel. April 26, 2019. https://www.history.com/news/epa-earth-day-cleveland-cuyahoga- river-fire-clean-water-act

Campbell, John. "Ideas, Politics, and Public Policy." Annual Review of Sociology 28 (2002): 21-38.

Childress, Sarah. “Timeline: The Politics of Climate Change.” PBS. October 23, 2012. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/timeline-the-politics-of-climate-change/

Churchill, David. "Lesbian and Gay Rights in Canada: Social Movements and Equality-Seeking, 1971-1995 (review)." Journal of the History of Sexuality 10, no. 3 (2001): 587-88.

Falkner, Robert. "Global Environmentalism and the Greening of International Society." International Affairs vol. 88, no. 3 (2012): 503-22.

Hall, Peter A. "Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain." Comparative Politics 25, no. 3 (1993): 275-96.

“How gun control advocates are creating change.” February 22, 2018 on USA Today. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b2B6N966rsE&feature=youtu.be

“How to Succeed as an Idea Entrepreneur, with John Butman | Big Think Mentor.” August 14, 2013 on Big Think. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8RX_pdlXQJQ&feature=youtu.be

John, P., 2003, Is there life after policy streams, advocacy coalitions and punctuations: Using evolutionary theory to explain policy change? Policy Studies Journal, 31(4), pp. 481–498.

Lindsay, Bethany. “Money laundering funded $5.3B in B.C. real estate purchases in 2018, report reveals.” CBC. May 8, 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/laundered-money-bc-real-estate-1.5128769

March, James, and Johan Olsen. Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics. 1989.

McBride. Alannah., Bartlett. Randall, and Canadian Electronic Library. National Pharmacare in Canada : Choosing a Path Forward. Documents Collection. 2018.

Nossal, Kim Richard, Roussel, Stéphane The Politics of Canadian Foreign Policy. Fourth ed. Queen's Policy Studies Series. 2015.

Olsen, Johan, and James March. "The Logic of Appropriateness." IDEAS Working Paper Series, 2004.

Paris, Roland. “Are Canadians still liberal internationalists?” OpenCanada.org. September 25, 2014. https://www.opencanada.org/features/are-canadians-still-liberal-internationalists/

Pratt, Cranford. Middle Power Internationalism the North-South Dimension. Kingston, Ont: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1990.

“Punctuated Equilibrium: An Introduction.” April 20, 2015 on Urban Policy Lab Konstanz. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jX2ecS7ri2I&feature=youtu.be

Rocher, Guy. "J.L. GRANATSTEIN, The Ottawa Men. The Civil Service Mandarins, 21935-1957." Recherches Sociographiques 25, no. 3 (1984): 488.

Scott, Haley J. Global Financial Crisis. Global Economic Studies. New York, NY: Nova Science Publ, 2010.

Stuart, Rob. “Was the RCN ever the Third Largest Navy?” Canadian Naval Review 5, no. 3 (2009): 4-9.

“United at War | Canada: The Story of Us, Full Episode 8.” May 28, 2018 on CBC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDwPMPczwvc&feature=youtu.be

Wilson, Jason. “Revealed: nine more US states considering hardline anti-abortion bills.” The Guardian. May 15, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/14/six-week-abortion-bans-faith2action

Supplementary Resources

- Béland, Daniel, Martin B. Carstensen, and Leonard Seabrooke. "Ideas, Political Power and Public Policy." Journal of European Public Policy 23, no. 3 (2016): 315-17.

- Chandler, J. A. Public Policy and Private Interest : Ideas, Self-interest and Ethics in Public Policy. Routledge Textbooks in Policy Studies. 2017.

- Hogan, John, and Howlett, Michael, Editor. Policy Paradigms in Theory and Practice: Discourses, Ideas and Anomalies in Public Policy Dynamics. Studies in the Political Economy of Public Policy. 2015.