Developed by: Dr. Martin Gaal – University of Saskatchewan

Overview

In Module 3, we mentioned how we would be looking in-depth at three elements which are important mutually constitutive elements of the policy environment:

- Institutions: both formal organizations and the informal patterns of rules, norms, and practices that shape the behaviour of actors

- Interests: a wide range of forces that create contextual frames that motivate individuals and organizations to be deliberate and act in particular ways.

- Ideas: both conscious and sub-conscious frames that shape beliefs and subsequently constrain or facilitate new ideas as policy solutions.

In Module 3, we introduced the concept of ideas and how ideas play a role in public policy and tested these propositions against Canadian Middle Power internationalism. The objective was not to ‘prove’ that ideas are the sole determinant of public policy but rather to demonstrate the role that ideas can play in public policymaking. We examined the way different ideational concepts can obstruct or facilitate the public policy process. More specifically, we looked at how ideas consciously and, perhaps even more importantly, subconsciously act as a filter to determine what actors should do in any given context. However, we also introduced the important caveat that ideas often work in a mutually constitutive logic with interests and institutions in the policymaking process.

In this module, we will be turning to the second of these three concepts: interests. Interests are the most operationalized variable in public policy analysis since this often motivates actors to seek change or defend the status quo. It is interesting to contrast this with the role of ideas in Module 3. Cognitive paradigms, normative ideas, or world culture may shape what an actor believes to be true, right, and/or appropriate. But that alone may not be enough to motivate an actor to try and influence public policy. On the other hand, if threatened and if important enough, interests often will motivate action: lobby decision-makers, join political parties, march in rallies, donate to causes, start new social movements, et cetera. Think of the example given in Module 3 on the Alabama legislation, which makes abortions illegal and can punish those who perform abortions with 99 years in jail. Most people have ‘ideas’ on abortion. Those who are adamantly pro-life or pro-choice will often advocate on behalf of these ideas that they believe to be true, right, and/or appropriate; think of all the social media posts you might have seen. But until people’s interests are at stake, those actively and consistently involved in advocacy, beyond a Facebook post, tend to be a relatively small minority. Once the Alabama law takes effect, many more people will be interested in supporting or opposing the law, both in and beyond Alabama. Doctors and other health care workers will have an interest in the debate. Women’s reproductive rights activists will have an interest in the debate. Women more generally will be interested in who can and cannot legislate on their reproductive rights. Those with a strong moral stance on either side will have an interest in the debate. This demonstrates that while ‘ideas’ matter, they may require some trigger to motivate action. And this trigger is often a perceived opportunity for or threat to one’s interests.

Figure 4-1: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/banner-header-i-you-and-finger-1071785/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

In order to address the role of interests in comparative public policy, we will begin with an examination of the concept itself – what are interests? We will then look at the dominant approach to understanding the role of interests in public policy, Rational Choice Theory, and the approaches that have emerged from it. Next, we will look at the role of interest groups in pursuing public policy options. Finally, we will finish with a case study of how interest groups react when the government changes.

However, as introduced in Module 3, we need to be careful not to overemphasize the role interests play in public policy vis-à-vis interests and institutions. It can be difficult to differentiate between ideas and interests. Think of the case study in Module 3, the shift in Canadian Foreign Policy post-World War II. It is clear that the ‘ideas’ held by decisions makers about how the world worked and what Canada’s role in that world should be had shifted. Prior to World War II, Canadian Foreign Policy had been dominated by an isolationist logic. After World War II, Canadian Foreign Policy was increasingly dominated by a liberal internationalist logic. But was this shift explainable by ideational changes alone? Or are interests playing a role here? Was the national interest of Canada, as defined by policymakers, best served by internationalism in the postwar world? Were the interests of a new and active foreign policy elite served by an internationalist role? An argument can be made that there is a confluence of interests and ideas here. However, to be clear, this doesn’t detract from the argument made about the role that cognitive paradigms, world culture, and normative frameworks played in shaping Canadian Foreign Policy decision making. It does, however, highlight how ideas and interests may be mutually reinforcing. We will also see in the next module how the role of interests can be conflated with institutions. Are your interests solely defined by your own preferences or are they a function of the institutional framework within which you reside? We will see that this, too, can be a vexing question. However, as we did in Module 3, we will isolate one of these three variables, interests, and look at the role they play in the public policymaking process.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define the concept of ‘interests’ in public policy.

- Critically analyze the dominant theories that utilize the concept of interests in public policy analysis, including Rational Choice Theory and its derivatives.

- Critically analyze the form and function of interest groups in comparative public policy.

- Assess the relationship between interest groups and government during times of transition, using a case study example.

- Institutions

- Ideas

- Interests

- Public interest

- Common good

- Public goods

- Egotistically / Self-interest

- Market goods

- Win-win situation

- Public interest

- Trigger

- Zero-sum game

- Rational Choice Theory (RCT)

- Bounded rationality

- Satisfice

- The tragedy of the commons

- Collective action problems

- Budget-maximizing model

- Elite theory vs. Pluralism

- Interest groups

- ‘Insider’ group vs. ‘Outsider’ group

- Pluralism

- Corporatism

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

Cigler, Allan J., Loomis, Burdett A.. Nownes, Anthony J. “Introduction: The changing nature of interest group politics”, Interest Group Politics. Ninth ed. 2016. [See file in Canvas]

Struzik, Ed, “Canada’s Trudeau is under fire for his record on green issues”, Yale Environment 360. January 19th, 2017. https://e360.yale.edu/features/canada_justin_trudeau_environmental_policy_pipelines [Online link; for Learning Activity 4-4]

Fillmore, Nick. “Opinion: why are Canada’s environmental groups going along with weak climate targets?”, Canada’s National Observer. November 1st, 2016. https://www.nationalobserver.com/2016/11/01/opinion/opinion-why-are-canadas-environmental-groups-going-along-weak-climate-targets [Online link; for Learning Activity 4-4]

Learning Material

Introduction

Ambrose Bierce (1911) famously suggested that ‘politics’ referred to the ‘strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles.’ This cuts to the heart of politics and public policy. Politicians and governments cannot do everything. Sometimes they cannot even do all that they want. Their actions are bounded by a finite amount of capital, both material and political, to create policies to achieve the most important goals to them and their constituents. That is not to suggest all politics is a zero-sum game. But there are limits to what decision-makers can pursue in terms of policy initiatives. They must pick and choose their battles and only take on what they believe to be ‘doable’. Think back to Module 2 and the differences between the systemic and institutional agendas. The systemic agenda is composed of all those issues different groups want decision-makers to act on. The institutional agenda contains those issues that decision-makers will, at the very least, consider acting on. This, by its very nature, creates tension at multiple levels:

- It creates tension between decision-makers and those advocating for particular policy options.

- It creates tension between different groups advocating for different policy options in the same policy area.

- And it creates tension between different groups, advocating for action in different policy areas.

It creates tension because each group is making a claim on some of that finite capital that decision-makers have control over. They seek to claim this capital to pursue policies they perceive to be in their own interest and/or in the public interest more generally. Importantly for us, the keyword here is ‘interest’.

Figure 4-2: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/me-you-selfish-contest-compare-1767683/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of johnhain.

This module will look at arguments that suggest both politics and policymaking are best understood as a contentious pursuit of interests. This is certainly the case for rational choice theorists, critical theorists, and theorists of interest groups, to name a few. Each approach looks at the form and function of interests slightly differently. These differences have implications on how each theorizes the role of interests in influencing policymaking. Yet, a common problem is the ambiguous nature of the concept of interest itself. There is no universally accepted definition of interests, and as Blyth (2003) argues, interests ‘are far from the unproblematic and ever-ready explanatory instruments we assume them to be.’ When we speak of interests in everyday language, we separate them from wants, desires, and beliefs. But if we are trying to understand what motivates behaviour, it is much more difficult to separate interests from these and other concepts.

Despite the ambiguity around the definition, the concept of interests is core to the field of public policy. In the first section of this module, we will first define the concept of interests in public policy and then introduce theoretical approaches that suggest interests play a determining role in public policymaking. The first is Rational Choice Theory, one of the dominant approaches used in public policy analysis. We will also look at some of the problems Rational Choice Theory identifies, including the ‘tragedy of the commons’ and collective action problems. Building off Rational Choice Theory, we will explore other influential models that privilege interests, Elite Theory, and critical public policy theories.

In the second section, we will look at the role that interest groups play in public policy. It will be argued that interest groups are associations constituted by individuals or organizations that seek to influence public policy.

Finally, we will close with a case study of how interest groups may reorient themselves when dealing with a new government.

Before moving on, I want you to think of an interest group that you think exerts the most influence over:

- The Canadian Government

- The Provincial Government

- The University

Post your top answer for each institution on the following Padlet board. On this board, you can also “upvote” / “downvote” posts that you agree or disagree with.

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include:

- Your Padlet contribution

- The Padlet contribution by one of your classmates and why you think this is a strong contribution

The Definition and Use of Interests in Public Policy

Defining Interests

We can most broadly define the role of interests in public policy as the competing goals of the many actors seeking to influence:

- The policies that are to be included in the institutional agenda.

- The final form those policies might look like if they do make it onto the institutional agenda.

In each case, the actors involved seek to promote and shape policies that they perceive to benefit them, to society more generally, or sometimes to both.

Figure 4-3: The “public interest” / “self-interest” spectrum. Permission: Courtesy of Distance Education Unit, University of Saskatchewan.

Figure 4-4: Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/calculator-calculation-insurance-385506/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of stevepb.

For example, large corporations may advocate for policies that lower tax rates to establish new business operations. This does not mean that these corporations believe they are harming the public if and when such concessions are negotiated. Quite the contrary, they believe that by enhancing corporate profitability, they can establish sustainable enterprises that provide good jobs for the local community and create opportunities for other companies to support or service their operations. This cumulatively grows the economy, the tax base, and generates wealth for and in the community. And they do not deny that they too will profit – perhaps even more than the community they are negotiating with. Such corporate arguments are described as a win-win situation. Essentially, they are arguing their interests are also in the community’s interests. Whether this win-win argument is genuine or just rhetorical does not change the fact that they are acting egotistically: acting on and for their own narrowly defined self-interest. If there was no benefit for themselves or those they represent, they would not be trying to convince decision-makers, nor the wider public, that they should be given tax concessions. Further, local taxpayers may not see this as a win-win situation if they are asked to shoulder a larger tax burden in the process, perhaps to provide environmental protection or to provide more public services. In such cases, it is important to look at what is being asked for, who will benefit, and what the costs of this may be to others and the community as a whole.

On the other end of the spectrum, individuals and groups advocate for the public interest, for example, seeking investment in public infrastructure, tougher environmental standards, or perhaps the protection of civil liberties and human rights. However, the public interest is another difficult concept to define precisely. It loosely correlates with the ‘common good’ or ‘common interest’. But it lacks a clear legal definition. This was made clear in the Canadian Supreme Court case R. v. Zundel (1992), where it is noted that the term ‘public interest’ is used, and not always consistently, 224 times in 84 federal statutes. This number grows exponentially if we were to include the numerous provincial statutes.

Figure 4-5: Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/lCPhGxs7pww Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Alexander Mills on Unsplash.

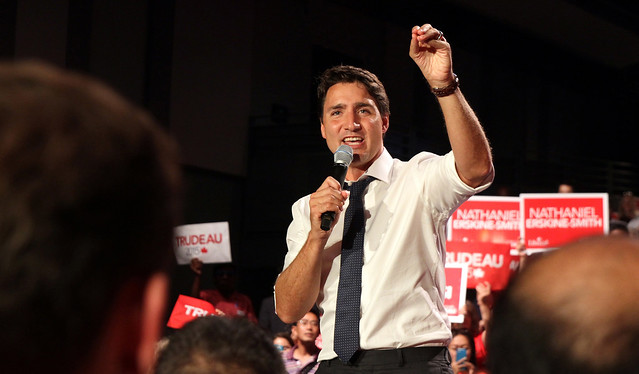

It is perhaps easiest to recognize the public interest if we contrast it to self-interest. Self-interested actions or policies benefit an identifiable subset of society: a person, group, organization, or corporation – like the corporation mentioned in the above example on tax concessions. Further, the beneficiaries of public policies are most often the wealthy and/or elite due to their relatively greater access to, and influence over, decision-makers. This was clear during the SNC Lavalin affair in the Spring of 2019, where the company’s access to Prime Minister Trudeau’s Office became a topic of controversy. SNC used its access to the PMO to lobby for a deferred prosecution agreement against bribery and fraud charges over its operations in Libya between 2001 and 2011.

On the other hand, actions or policies in pursuit of the public interest benefit the general public. Often, a key distinction between self-interest and public interest is the difference between market goods and public goods. The market is a pretty good mechanism to facilitate a process of exchange between buyers and sellers of commodifiable goods and services. In so doing, the market is balancing the competing interests of private individuals. Public goods, on the other hand, are those goods and services that are not easily profited upon, such as sidewalks or street lighting; those goods and services that society decides shouldn’t be exclusive to those who can afford it, such as education, health care, or public transportation; those goods and services which protect society from unscrupulous actors seeking their narrowly defined self-interest, such as regulatory bodies on health, safety, and the environment. In well-functioning states, public authorities provide these goods, like the municipal, provincial, and federal governments in Canada. However, before such public goods become government policy, they are often first found on the systemic agenda supported by people advocating for the public interest.

Figure 4-6: Market goods. Source: https://www.pexels.com/photo/stock-exchange-board-210607/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Pixabay. |

Figure 4-7: Public goods. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/health-care-medicine-healthy-2082630/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of ar130405. |

Using Interests: Rational Choice Theory

One of the most important frameworks used in public policy to operationalize the idea of interests is Rational Choice Theory (RCT). RCT borrows from the field of economics, seeking to quantitatively model what actors will likely do in given contexts. It posits human behaviour is determined by instrumental reason: humans making choices that they perceive to be the best means to achieve their preferences and/or interests. Moreover, it is argued that this logic of individual choice can be aggregated to understand how groups will act, up to and including society as a whole. While in the field of economics, the rationality conditions can be quite stringent, they are often simplified in the social sciences, at least as a starting point, to include:

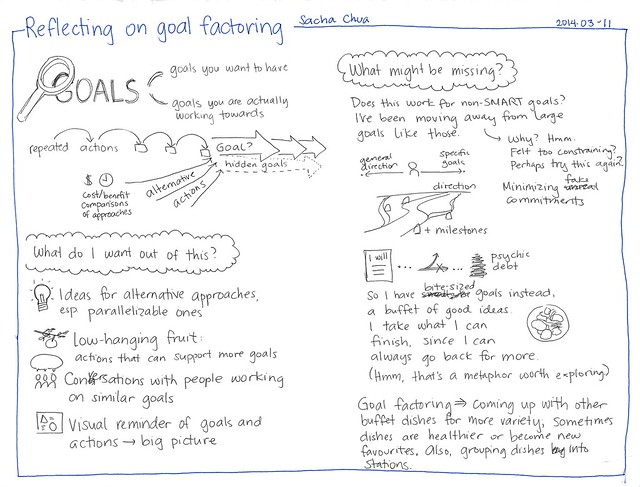

Figure 4-8: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sachac/13107850844/ Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Sacha Chua.

- Complete information: actors are aware of all the choices available and the consequences of those choices.

- Stable and complete preferences: actors prefer A to B, B to C, and A to C.

- Sufficient time: actors have the necessary space and time to make the best choice to achieve their preferences/interests.

This provides decision-makers with generalized predictions about how people will react to policies and whether the policy will have the desired effect. Essentially, RCT argues that when individuals act rationally and freely, they will make choices that they believe will further their interests within the context they are operating in. Further, if we can predict what individuals are likely to do, we are able to predict aggregate social behaviour.

There are criticisms of RCT, especially where it has failed to predict outcomes. It seems people do not always act ‘rational’ or rational as defined by RCT. Therefore, some have modified RCT to provide a better fit with real-world circumstances, which often does not allow for perfect information, stable and complete preferences, and/or sufficient time. For example, bounded rationality is used to explain when information and time are limited or when actors are constrained by personal bias, encouraging actors to ‘satisfice’: to choose the first option that meets the needs of a problem or directive from above. However, at the aggregate level and over time, RCT is ‘right’ often enough that it has proven to be a powerful framework in the field of public policy.

Insights from Application of RCT

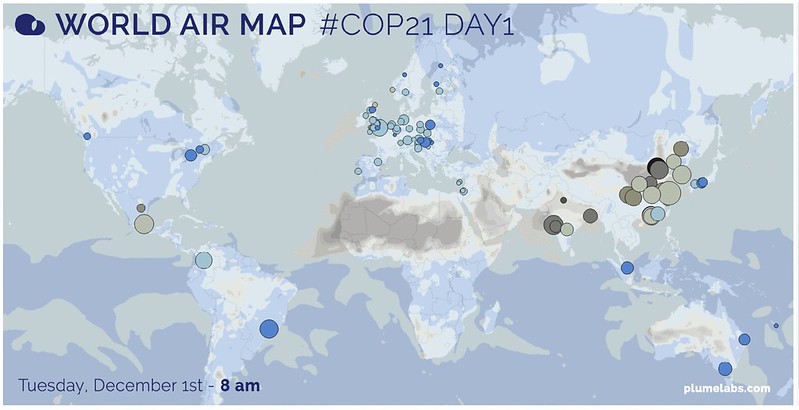

Over time, the application of RCT has also produced some specific insight into public policy issues, such as the ‘tragedy of the commons’ and ‘collective action’ problems. The ‘tragedy of the commons’ refers to the short-term self-interest involved in overusing common resources or polluting common resources. For example, imagine a group of ranchers with access to both their own private grazing land and common grazing land. RCT would suggest there is a strong incentive to use as much of the common grazing land as possible and to do so as quickly as possible since the other ranchers have the same incentive. Acting on this short-term self-interest may, in turn, degrade or destroy the common resource in the long term, harming everyone’s interests. And yet, the dominant logic is still to over-utilize the common good until it is gone. We have seen this logic at work in global environmental problems like international fishing, ocean pollution, and atmospheric pollution. These are examples of global commons in that they are not ‘owned’ by anyone, and hence there is little incentive, according to RCT, to protect and preserve them.

Figure 4-9: The tragedy of the commons – global air pollution. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/stromreport/23565682946/ Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Strom-Report.

Research on the ‘tragedy of the commons’ has produced three policy options:

- Garret Hardin (1995), who coined the term ‘tragedy of the commons’, suggested two of these options: either regulate the commons through top-down government intervention or privatize the commons. This would break the incentive to abuse the commons and allow for both positive and negative instruments to condition actors’

- Ostrom (1990), on the other hand, challenged Hardin’s options, instead advocating for the local management of common-pool resources. She used examples from Maine, Indonesia, Nepal, and Kenya to demonstrate that it is possible to have effective grassroots management of common resources without top-down intervention or privatization when governance is localized.

Figure 4-10: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/nature-conservation-responsibility-480985/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Mysticartdesign.

The second public policy issue that has been identified in the RCT approach is the problem of collective action. A ‘collective action problem’ exists when providing a good or service will benefit a group of people, but the cost of providing it is difficult or impossible for one person to provide alone, and conflict between actors prohibits them from working together to provide it. Olson (1982) argues the difficulty of collective action correlates with the size of the group: as the group size increases, so do the challenges of collective action. This is because as the group grows, each person’s share of the good decreases. This creates disincentives for action. Further, as the group grows, there is greater opportunity for ‘free-riding’: benefiting from the good or service without contributing to its provision. For example, we all benefit from healthy international fish stocks. However, according to RCT and the ‘tragedy of the commons’, there is an incentive to overfish in international waters. This is a collective action problem because the group size is very large. Rogue fishing fleets or even fleets supported by rogue governments may gamble that if everyone else follows the rules, they can free ride: continue to overfish hoping that the others do not and thereby allowing them to maximize their interests without paying the costs associated with fish stock depletion. Olson (1982) argued that in such cases, there is a need for effective monitoring of the commons as well as positive and negative instruments to discipline behaviour in the commons.

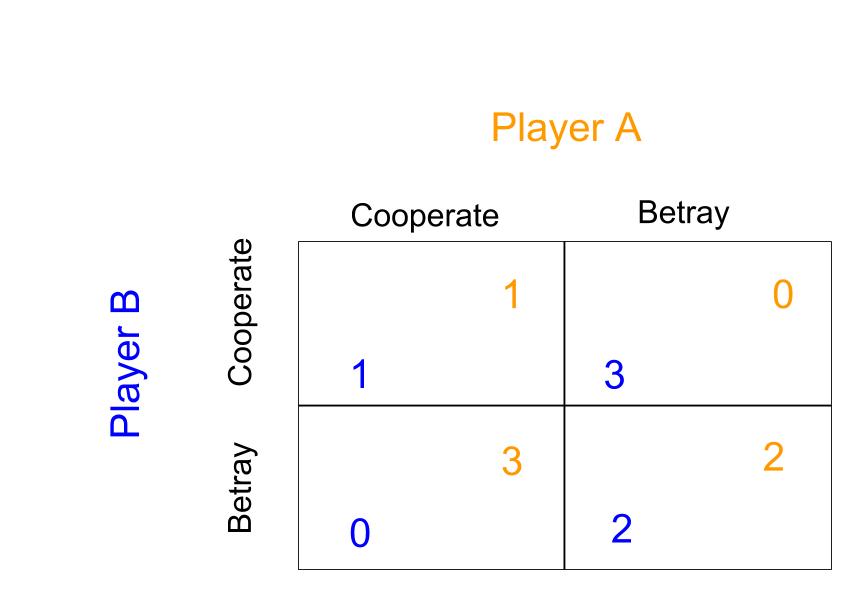

Figure 4-11: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Prisoner%27s_Dilemma.jpg#/media/File:Prisoner’s_Dilemma.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Nber85.

Theories Derived from RCT

Finally, it is important to note theories that have developed out of RCT or have adopted elements of its logic in their function. William Niskanen (1971) reviewed the approach to government bureaucracy developed by Max Weber which had become orthodoxy. As an organizational form, Weber argued bureaucracy promoted neutrality amongst civil servants and therefore promoted a commitment to the public good. Niskanen, utilizing RCT, identified a contrary logic at work he called the budget-maximizing model. He posited that civil servants would be more likely to pursue their own sectional interests than pursue the public interest. He argued that as rational actors, bureaucrats would seek to maximize their budget and the size of their department or bureau, even to the detriment of the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the bureaucracy as a whole.

Elite theory is an extension of Marxist theory that also incorporates RCT and stands in contrast to pluralism. Pluralism is the theory that democratic society is constituted by a multitude of rival groups, all competing for power, and in so doing represent the aggregate will of society. On the other hand, Elite theory suggests that a small minority, constituted by the economic elite and those who control the levers of policy planning, will manipulate politics for their own ends rather than the broader public good. They are able to do so because the elite stand as a group united in their common class-based interests while the non-elite are a diverse group with a diverse, and at times conflictual, sets of interests. This positionality is further reinforced by the elites privileged access to those in power which allows them to ‘game’ the system, often unchecked. For example, the previously mentioned SNC Lavalin controversy demonstrated how the wealthy and powerful have greater access to key decision-makers and may also have power over them. If the Attorney General at the time, Minister Wilson-Raybould, or one of her inner circle, had not brought the issue into the public domain, it is unlikely we, as the general public, would have ever heard of this scandal. From the definition of interests to RCT and the theories/concepts derived from RCT, it should be clear that interests play a pivotal role in the processes of public policy and public policy analysis.

Figure 4-12: SNC Lavalin. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SNC-Lavalin_logo.svg#/media/File:SNC-Lavalin_logo.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of SNC-Lavalin Rail & Transit. |

Figure 4-13: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Justin_Trudeau_in_Lima,_Peru_-_2018_(41507133581)_(cropped)_(cropped).jpg#/media/File:Justin_Trudeau_in_Lima,_Peru_-_2018_(41507133581)_(cropped)_(cropped).jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Presidencia de la República Mexicana. |

Figure 4-14: Former Attorney General and Minister of Justice Jody Wilson-Raybould. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jody_Wilson-Raybould_(cropped).jpg#/media/File:Jody_Wilson-Raybould_(cropped).jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Erich Saide. |

Watch Elizabeth Pisani’s TED Talk “Sex, Drugs, and HIV – let’s get rational’ https://youtu.be/LoXAAEy6YQU

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- For a drug addict, what defines rational choice in the following situations:

- In prison and offered a dirty needle with your drug of choice.

- On the street where carrying a clean needle can lead to your arrest.

- On the street with access to a safe injection site.

- For an at-risk demographic, what defines rational choice, in the following situation:

- Use of condoms when HIV is increasingly treatable.

- Engaging in sex work in a low GDP country.

- For a government, what defines rational choice in the following situations:

- High IV drug use/large sex worker population and a publicly funded health care system.

- High IV drug use/large sex worker population and private health care.

- High IV drug use/large sex worker population and a strong moral opposition to both in the population.

- How does this TED Talk highlight:

- The problem of rationality?

- Implications for public policy decision making?

Interest Groups and Comparative Public Policy

Defining Interest Groups

Figure 4-15: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/luismaram/3106549172/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Luis Maram.

While we looked at the definition of interests and the dominant theories that utilize the concept of interests in public policy, we have missed the proverbial elephant in the room: interest groups. Think back to our working definition of interests in pubic policy – the competing goals of the actors who are trying to get their issue on the institutional agenda and shape the subsequent form of such policy if successful. Interest groups play a crucial role here. The concept of ‘interest groups’ covers a broad range of associations constituted by individuals or organizations seeking to influence public policy. These groups unite to apply pressure on decision-makers and influence public opinion in order to push policy in a particular direction. In reaction, other competing interest groups often unite to oppose them. For example, a group of businesses or a business association may form an interest group to pursue the repeal of legislation that is contrary to their economic interests. In response, a group of unions or a labour association may form to oppose their efforts to repeal the legislation if they perceive such action to be contrary to the interests of their membership. We will speak to the different types of interest groups in a moment, but they all by and large share three common features:

- First, they all have some formalized structure, albeit with great variance in degree. Some interest groups are as minimal as a Facebook page and a contact email, especially when starting out. Others can be multimillion-dollar organizations with chapters around the world and offices situated at the heart of decision-making bodies.

- Second, interest groups all seek to foster consensus within its membership and advocate for those agreed positions with both the general public and with decision-makers.

- Third, interest groups are distinct from political parties. They try to influence the public and decision-makers, but they generally do not seek to be the decision-makers.

4 Types of Interest Groups

In order to understand the role of interest groups, it is useful to look at the different forms they take and the different ways they operate. While there are several different models of interest group categorization out there, we are going to look at four types of interest groups and how to predict their relative influence.

1. Interest groups motivated by narrowly defined economic interests

The first type of interest group is motivated by narrowly defined economic interests. These groups seek to influence public policy at every stage of the policy cycle: from influencing systemic and institutional agenda setting through to the evaluation stage, specifically political and judicial evaluation. For example, in an effort to legislate action on climate change, the Trudeau Government introduced the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GGPPA), in March of 2018. This applies a federal carbon pricing system in provinces that have not implemented their own systems. A variety of interest groups have tried to influence the federal policy on carbon pricing at every stage of the policy cycle including judicial evaluation. For example, when Saskatchewan fought the GGPPA in court, many groups sought intervenor status which would allow them to participate in the judicial evaluation. One of those groups that asked for and was granted intervenor status was the Agricultural Producers Association of Saskatchewan (APAS). The APAS believed that the GGPPA was a threat to their membership’s interests. It would raise their production costs without an easy means to pass on such costs to consumers and put them at a disadvantage to competitors not facing increased costs. This is an example of both a standing interest group, defending the interests of Saskatchewan farmers and a group that acts with others when they perceive something to be a threat to their interests, such as the GGPPA. These interest groups align closely with the naked self-interest introduced in the first section of this module.

Figure 4-16: Farmer protest in Ottawa, 2005. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/thelastminute/123895348/ Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Duncan Rawlinson.

2. Public interest groups

The second type of interest group is also familiar from the first section of this module, public interest groups. These groups are motivated by interests that their members believe to be in the general interest. These groups believe that their advocacy will be of benefit to those far beyond their membership. They often engage in issues of civil rights, human rights, animal rights, and environmental issues, for example. Take environmental interest groups for example. If you were disturbed by the decision of Brad Wall’s government to cut local funding for the Meewasin Valley Authority (MVA) in 2017, you might have joined the ‘Keep Meewasin Vital’ group. It has sought to pressure the Provincial Government to restore funding so that the MVA can continue to protect the river valley habitat and provide environmental education programming. If you were concerned with the loss of biodiversity at the provincial level, you might have joined the Saskatchewan Environmental Society which is advocating for increased biodiversity protection in the province. If you were concerned with oil tankers off the north coast of BC, you might have joined West Coast Environmental Law, advocating for a moratorium on tanker traffic. If you were concerned with global climate change, you might have joined Climate Action Network Canada, advocating nationally and internationally for policies that reduce the human impact on the global climate system. These are all examples of people forming or joining public interest groups to address issues that they believe to benefit not just them but also to a much wider public: the residents of Saskatoon, of Saskatchewan, of Canada, or of the world. While public interest groups are also often involved in every step of the policy cycle, they are much more influential in the agenda-setting stage. Public interest groups are most often seeking to move items from the systemic agenda to the institutional agenda. For example, putting MVA funding, biodiversity protection, oil tanker regulation, or climate change policy on the institutional agenda.

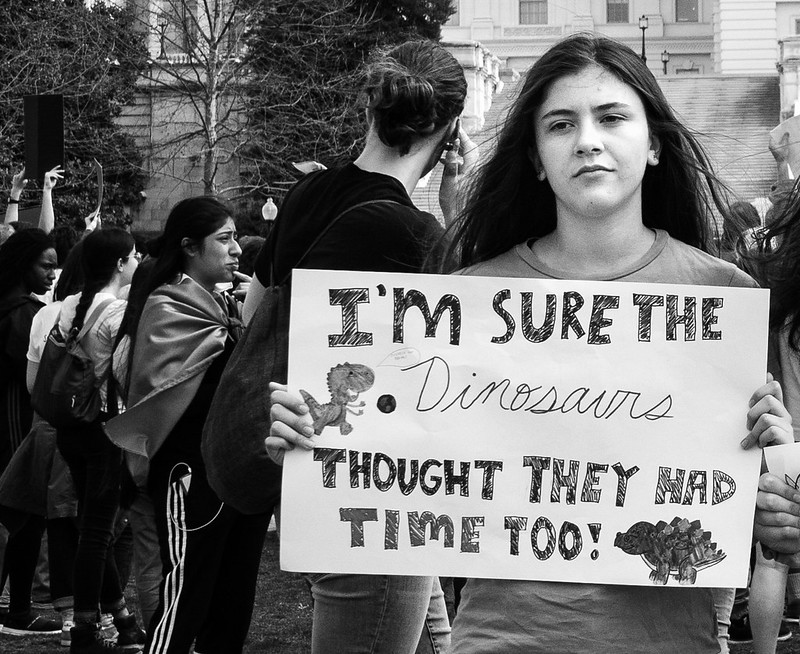

Figure 4-17: Youth Climate Strike, 2019. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vpickering/47445663891/Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Victoria Pickering.

3. Governmental interest groups

The third type may seem to be an odd fit, governmental interest groups. Most countries have multiple layers of government. In Canada for example, the most important layers include the federal, provincial, and municipal governments. Within these layers are groups of actors with potentially competing interests. As policy insiders, these interest groups can be involved in every step of the policy cycle but are most influential in the policy formulation and policy decision making stages. For example, western Canada may be more pro-resource extraction while central Canada may be more pro-manufacturing or services industry. Therefore, provinces in western Canada may work together to advocate for their economic interests in Ottawa as well as in the general public while central Canada may do the same albeit at possible cross purposes to western Canada. Interest groups are one way to do this. For example, the Canada West Foundation plays an important role in advocating for resource extraction and the governments of Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan are all-important donors. As such, they have insider access to decision-makers. Another example is the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, which advocates for issues important to local governments. These include affordable housing, infrastructure development, cannabis legalization, climate change, public safety, public transportation, rural issues, and equitable burden-sharing for addressing such issues. These are all examples of groups advocating for, at least in part, governmental interests.

Figure 4-18: The Federation of Canadian Municipalities – Sustainable Communities Conference 2010. Source: https://flic.kr/p/7FZuSN Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of The Natural Step Canada.

4. Interest groups that advocate on behalf of a single issue/cause

The fourth, and last, type of interest group advocates on behalf of a single issue or cause. Similar to groups driven by narrow economic interests, these groups represent segments of society. However, the difference is that the goal of single-issue interest groups is non-economic. They may be advocating on behalf of a cause such as people with disabilities, veterans, or religious organizations. They may be advocating for a single issue, such as women’s reproduction rights, against drunk driving, gun control, or Indigenous rights. The range of topics that single issue or cause interest groups advocate for is wide-ranging. However, they all seek to promote something that they believe to be normatively right. Like public interest groups, single-issue groups are often most effective at the agenda-setting stage of the public policy process. They seek to move issues from the systemic agenda to the institutional agenda.

Figure 4-19: Moms Demand Action Against Gun Violence, St Paul Minnesota. Source: https://flic.kr/p/27N2QL8 Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Fibonacci Blue.

Factors Impacting Interest Groups’ Influence on Public Policy

The degree to which interest groups are able to influence public policy can be assessed along a number of lines. Some of these criteria are more obvious. An interest group is more influential the larger the membership it has, the more homogenous the groups aims, and the more resources at its disposal. These allow an interest group to have greater visibility, influence public opinion, and carry more weight with the government.

However, perhaps the most important measure of an interest groups influence is whether it is an ‘insider’ group or ‘outsider’ group:

- Insider interest groups include all those who are involved in consultation and negotiation with the government, often even before the government’s own view has crystallized. These groups, therefore, have privileged access points to the government and can exert influence throughout the policy cycle. For example, if the government is pro-business, then they are likely to have a closer relationship with pro-business interest groups and vice versa if the government is pro-labour. When a government sets its priorities, like being pro-environment or pro-gender equality, then groups associated with such issues may also be granted greater access. Other professional organizations, like the Canadian Medical Association or Law Societies, also have insider access when the government is working on policies related to their areas of expertise.

- In contrast, ‘outsider’ interest groups lack these access points with the government. For some groups, this is deliberate, as they believe the close association with the government can delegitimate their actions. For example, an NGO like Doctors Without Borders or Transparency International may choose to pressure the government and believe too close of an association would undermine their work. For other groups, they are more focused on influencing public opinion than they are on influencing government. Still, others are too small or lack enough resources to motivate governments to build connections with them.

Figure 4-20: Canadian Medical Association. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CMA_AMC.jpg#/media/File:CMA_AMC.jpg Permission: Fair Use. |

Figure 4-21: Doctors Without Borders in Darfur. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MSF_front_door_in_Chad.jpg#/media/File:MSF_front_door_in_Chad.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Mark Knobil. |

Theories of Interest Groups and Public Policy

Finally, there are two theories that try to make sense of interest groups and public policy.

Figure 4-22: Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/conference-leaders-politics-debate-156068/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of OpenClipart-Vectors.

The first, pluralism, was introduced earlier. As a theory of politics, Pluralism argues that in a liberal democracy, power is or should be dispersed amongst a number of different interest groups. These groups compete with each other to influence the policymaking process. This diversity is seen as a strength since it is argued competing interest groups act as a system of checks and balances on the consolidation of power within the system. This doesn’t mean that all groups are equal or that all groups are able to achieve their goals. It does mean, however, that groups a more likely to have to accommodate one another. And perhaps more importantly, the government will attempt to balance these groups’ most important interests being advocated for. There are criticisms of this approach as well. In the strongest variants of pluralism, the government is essentially a passive actor. It is argued to be simply balancing the demands made by a variety of interest groups, and its autonomy as a public policy actor is marginal. This is a claim that we will examine in more detail in module five when we look at the role of institutions.

Figure 4-23: Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/exchange-of-ideas-debate-discussion-222788/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

The second broad theory that applies the concept of interest groups is corporatism. Corporatism suggests some interest groups are more than just ‘insider’ groups. Rather it is argued some have a privileged and institutionalized role within the process of decision making. This is about more than an articulation of, and lobbying for interests. Rather it is an institutionalized pattern of policy-formation in which large organizations cooperate with each other and with public authorities. They do so to articulate their interests and infuse the system with their values. Corporatism has deep historical roots, stretching back to the European medieval guild system and the deep integration between the Roman Catholic Church and the state. Later, there were deep corporatist elements in the fascist governments of Italy and Germany as there were in other authoritarian states like Spain, Brazil, Peru, Mexico, and Greece. However, corporatism is also present in progressive and social democratic states like Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Norway and Denmark. These states have formalized neo-corporatist elements where business and labour have an entrenched relationship with the government. Austria is an interesting case. In Austria, all working citizens are obliged by statutory law to belong to a ‘Chamber’ such as labour, commerce, agriculture. These Chambers have the formal right to be consulted on and be represented in a wide range of matters, as well as to nominate members to many other public bodies. Critics of corporatism often see the potential for ‘state capture’. This is when the institutionalized arrangement of the interest group access to decision-makers becomes a conduit for the wealthy and powerful to subsume the government to their narrowly defined interests to the possible detriment of the public good. Interest groups play an instrumental role in public policy, whether fighting for the public good or for narrowly defined economic advantage.

Interests and Interest Groups in Public Policy: The Comparative Aspect

Finally, we will turn to the comparative aspect of interests and interest groups in public policy.

First, in our increasingly globalized world, interests often transcend borders. For example, the interests of the elite in one state are often much more aligned with the elite in other states than they are with the non-elite in their own state. More specifically, consider the effect of the 2007-08 global financial crisis. As the subprime mortgage crisis in the US morphed into a global financial crisis, many countries adopted similar policy responses. These policies bailed out large Multi-National Corporations (MNCs), banks, and financial institutions, securing the interests of the wealthy and powerful. This allowed the global elite to rebound relatively quickly from the crisis, while the non-elite in many countries have had their savings depleted, their pensions eroded, their jobs eliminated, and been left with an uncertain future. In response to the financial crisis, we can see the comparative method at work. States looked to the policy responses of other states, converging on what was perceived to be the best response, or arguably at least the response that best protected the interests of the elite.

Second, much like we saw in the last module on ideas, interest groups will often look to the advocacy of other groups to identify strategies that have led to successful outcomes. Whether seeking narrow economic advantage, pursuing the public good, or advocating for a single cause, the goal of all interest groups is the same – to influence the public policy process. In order to maximize their influence, they will often seek to learn from both the success and failures of others. This is the essence of comparative public policy.

Figure 4-24: Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/influencer-influencer-marketing-4202697/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of DiggityMarketing.

Watch the VPAP video “What is an interest group?” https://youtu.be/UAZXFELMd2w

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- What is an interest group?

- What role do interest groups play in public policy?

- What interest group might you be interested in joining

- Think of another interest group that might oppose the one you joined.

- What is it?

- What does this tell us about the role of interests and interest groups in public policy?

- How might we undertake a comparative analysis of interest groups in public policy?

Case Study: When Governments Change

When the government changes, the institutional agenda will likely, at least in part, change. If the institutional agenda changes, there will be new opportunities and threats to interests. Established, or ‘insider’, interest groups may find their access curtailed. New and previously marginalized, or ‘outsider’, interest groups may find new access points opening up. That is not to suggest a complete break with existing relationships occurs after a new party takes power. Some issues are near-permanent fixtures in the public policy of particular states. In Canada, for example, resource interests, labour interests, business interests, Indigenous interests, and municipal interests will all have continued relationships with the federal government regardless of which party is in power. What might change is the relative strength of those relationships and the possible inclusion of new relationships advocating for different interests. At times of change, both the government and interest groups have to assess the best way to achieve their respective goals.

The 2015 Federal Election of Justin Trudeau and Environmental Interest Groups

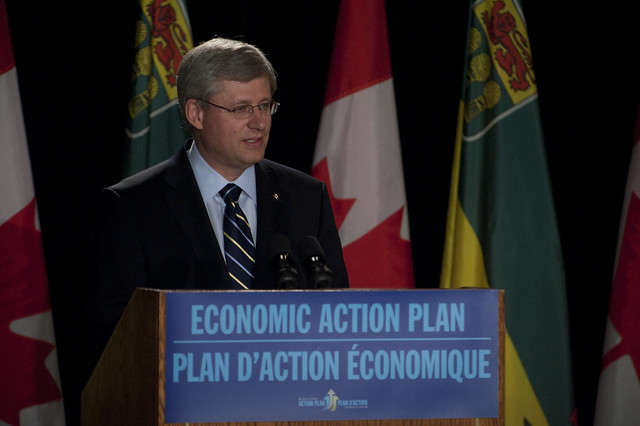

In the 2015 Canadian Federal election, the Liberal Party won a majority making Justin Trudeau the 23rd Prime Minister of Canada. His predecessor, Stephen Harper, had been PM since 2006. Under the Government of Stephen Harper, the institutional agenda had shifted dramatically towards the West, towards limited Federal power, and towards a much more circumscribed Canadian Foreign Policy. This meant promoting the energy sector, deregulating federal initiatives, cutting taxes, reforming the senate, and pulling back from the institutions of global governance.

Figure 4-25: Stephen Harper. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/usask/4990416118/ Permission: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Courtesy of University of Saskatchewan.

When Trudeau and the Liberals came to power, they shifted the government’s institutional agenda domestically and internationally. Domestically, promises were made to build a more inclusive and diverse government, with show-pieces like Trudeau’s first cabinet which was gender-balanced and had a very diverse membership. Promises were made to Indigenous peoples on addressing the many negative indicators of well-being and the national inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) was launched. Electoral reform and the legalization of cannabis were promised. Strong promises were made in terms of environmental stewardship and meeting the Paris Climate Agreement. Internationally, Trudeau promised to reorient Canada back to the Pearsonian legacy of being a “compassionate and constructive voice in the world”… He promised that ‘Canada was back’. In 2019, it is clear to see some promises were kept and some were abandoned – cannabis legalization versus electoral reform for example. Other issues areas are more complicated, with some gains and some losses. However, for the various interest groups in Canada, the 2015 change of government created a moment for reflection. Given the new institutional agenda, how would they best achieve their preferred policies on the institutional agenda and influence the final form of those policies that did make it there? If they were ‘outsider’ interest groups under the last government, should they try to cultivate an ‘insider’ strategy now? And vice-versa, if they were an ‘insider’ group under the last government, should they seek to maintain that relationship, or should they adopt the strategy of an ‘outsider’ interest group?

Figure 4-26: Justin Trudeau. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/alexguibord/23038696244/ Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Alex Guibord.

The various environmental interest groups in Canada provide an interesting case study. The Trudeau Government started strong on the environmental front. Soon after his victory, Trudeau promised to attend the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris, inviting all the provincial premiers to attend with him. He held a First Ministers meeting on climate change within 90 days, both promising to help provinces with their own plans to meet national emissions reduction targets and threatening a carbon levy if they did not. He promised to phase out subsidies for the fossil fuel industry. Instead, the policy would shift towards establishing and supporting sustainable and clean energy sectors. More promises were made for protecting coastlines, national parks, and freshwater sources. Trudeau reached out to Indigenous peoples, promising to consult more transparently on projects that would impact their traditional lands.

Figure 4-27: Justin Trudeau and AFN National Chief Perry Bellegarde. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/joshuatree/22990777283/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Renegade98.

Over the next four years, the Liberal Government’s record on the environment would be mixed. The government implemented a mandatory carbon price if a province had not established its own realistic plan to meet carbon emission reductions. Record levels of funding were committed to clean and sustainable energy technology. The Government recommitted to international agreements on the environment and climate change, like the Paris Climate Agreement, the G7 Oceans Plastic Charter, and contributions to cleaning the ocean. On the other hand, the Trudeau Government also spent 4.5 billion dollars to buy the Kinder-Morgan Pipeline, allowing tar sand oil development, making it very difficult to meet Canada’s emission targets under the Paris Climate Agreement. This tension was even more evident when the Government approved the Trans Mountain Pipeline the day after declaring we are in a climate emergency. Commitments to Indigenous peoples have been complicated by the shallow way the government has defined its ‘duty to consult’ – listening to issues raised by Indigenous peoples and responding meaningfully when possible. Responding ‘meaningfully when possible’ is far from the transparency promised when dealing with environmental issues that impact Indigenous peoples. On the whole, the Trudeau government has made a lot of promises on the environmental front. Some promises have been fulfilled, in-part or in-full. Some promises have been abandoned completely and others only in practice but not in rhetoric. Others are still on the institutional agenda but lack either visible progress or are being crowded out by other policies.

Figure 4-28: March to stop Trans Mountain oil pipeline. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/sallybuck/30501286358/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Sally T.Buck.

So, this brings us back to our earlier question: what are environmental groups in Canada to do? Under Harper, these groups had been clearly on the outside while the government deregulated environmental protection, invested in and expanded on fossil fuel extraction and, more specifically bitumen, argued for more exploratory drilling in the arctic, and backed away from international efforts to address the issue of climate change. With the election of Trudeau, environmental interest groups perceived an opportunity to come in from the outside. They perceived an opportunity to become an insider group that could influence policy decision-making and regularly consult policy options. But being on the inside track also has its downsides. To be effective as an insider, you need to be seen as a ‘team-player’ as your ability to influence policy can be dependent on your relationship with the government and policymakers. This might prove challenging as the Trudeau Government may be more pro-environment than the Harper Government, but the environment is only one of many issues they are dealing with. They have also to contend with challenges to economic growth, which may be a more salient issue for the public than the environment. This tension between issues like the environment and the economy has electoral implications, and re-election is always on or near the top of a government’s priority list. Environmental interest groups must undertake a cost-benefit analysis: does being a team player and being granted greater access to the policymaking process outweigh the cost of sacrificing a degree of autonomy? Does being an insider better meet their immediate and long-term goals better than fighting the good fight on the outside?

This case study highlights the degree to which the orientation of the government has a potentially determinative role in how interest groups seek to achieve their aims. In the sense of comparative public policy analysis, this suggests there is utility in examining the interplay between interest groups and the government. We can compare changes in the orientation of a single interest group when the government changes. We can compare how different interest groups working on the same issue area may orient themselves differently with the same government. And we can compare how interest groups working in different areas have differing access to the government. Such a comparison aims to assess the role of interests and interests groups in the public policy process.

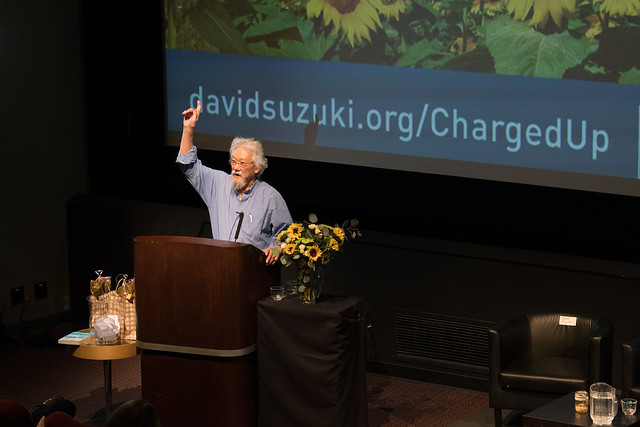

Figure 4-29: David Suzuki. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/dsf_canada/27809580298/ Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of David Suzuki Foundation.

If you haven’t already, read the Nick Fillmore and Ed Struzik articles (also listed in the Required Readings section of this module):

- Nick Fillmore’s article “Opinion: Why are Canada’s environmental groups going along with weak climate targets?” https://www.nationalobserver.com/2016/11/01/opinion/opinion-why-are-canadas-environmental-groups-going-along-weak-climate-targets

- Please Note – you might have to register to read this article. However, it does not cost anything and you can cancel your registration after reading the article.

- Ed Struzik’s article “Canada’s Trudeau is Under Fire For His Record on Green Issues” https://e360.yale.edu/features/canada_justin_trudeau_environmental_policy_pipelines

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How does the environmental policy of the Trudeau Government compare to that of the Harper Government?

- What dilemma were environmental interest groups faced when the government changed from Stephen Harper to that of Justin Trudeau?

- If you were on the board of a prominent environmental interest group, with a larger membership, and strong reputation (think Green Peace Canada or the David Suzuki Foundation):

- Would you recommend trying to cultivate an insider relationship with the Trudeau government?

- Why or why not?

- What are the potential implications of each choice?

Conclusion

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the concept of the role that ‘interests’ play in the public policy process. Again, we began by recognizing that it is very difficult, if not dishonest, to argue that interests alone determine outcomes. In practice, outcomes are often a result of the complex interaction between ideas, interests, and institutions. However, as with ideas, it is useful to look for cases where interests played an interesting role in order to understand the potential causal relationships. Interests are perhaps one of the oldest variables recognized as driving policy advocacy and policy decision-making. As Bierce (1911) argued, politics is the ‘strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles.’ This quote highlights how interests are habitually in conflict. Different groups, both within government and on the outside, compete to have those issues they care about placed on the institutional agenda and to influence the shape those policies eventually take if decision-makers consider them.

In order to make sense of the role that interests played in policy advocacy and policy decision-making, we first defined interests as:

- The policies that are to be included on the institutional agenda.

- The final form those policies might look like if they do make it onto the institutional agenda.

We then further separated the concept of ‘interests’ into self-interest and public interest, with the former being primarily self-regarding and the latter being primarily other-regarding.

Next, we looked at the dominant theories that account for the role of interests in public policymaking, most notably Rational Choice Theory and derivative theories that emerged from its application: the ‘tragedy of the commons’, ‘collective action’ problems, the budget-maximizing approach to bureaucratic politics, and elite theory.

Following this, we established a basic typology of interest group types, including those driven by narrowly defined economic interests, those advocating on behalf of the public interest, governmental interest groups, and groups advocating for a single issue. We noted those attributes that make interest groups more or less influential: membership size, homogeneity, and whether they are insider or outsider groups.

Finally, we closed with a case study that looked at how environmental interest groups in Canada must potentially reassess the form and function of their advocacy given a change in government.

Before closing this module, it is again important to note the mutually constitutive relationship between ideas, interests, and institutions. We have looked at how interests play an important role in policymaking, but it should be noted that interests and ideas can be conflated, as mentioned in the last module: what is good for us can often be perceived as an idea that we believe to be right and good. As we will see in the next module, interests can also be conflated with institutions: structures may influence what is or is perceived to be in our interests. After examining the role of institutions in the next module, we will briefly close Module 5 with a discussion of this mutually constitutive relationship.

Review Questions and Answers

Interests are one of the most core explanatory variables in public policy analysis. Most actors will hold feeling as to whether something is good/bad, right/wrong, or effective/ineffective. These are the ‘ideas’ we discussed in Module 3. Interests are more directly things we consider to be important to us or to the public good. While we many hold ideas about something, it is most often a perceived threat or opportunity to interests that we believe to be important that triggers action. It is a perceived threat or opportunity to our interests that motivate everything from posting to Facebook through to mobilizing on the street and everything in between. However, more specific to public policy, we can define the role of interests as the competing goals of the many actors seeking to influence:

- The policies that are to be included in the institutional agenda.

- The final form those policies might look like if they do make it onto the institutional agenda.

The concept of ‘interest groups’ covers a broad range of associations, constituted by individuals or organizations, seeking to influence public policy. These groups unite to apply pressure on decision-makers and influence public opinion in order to push policy in a particular direction. In reaction, other competing interest groups often unite to oppose them. There are four broad types of interest groups:

- The first type of interest group is motivated by narrowly defined economic interests. These groups seek to influence public policy at every stage of the policy cycle: from influencing systemic and institutional agenda setting through to the evaluation stage, specifically political and judicial evaluation.

- The second type of interest group is public interest groups. These groups are motivated by interests that their members believe to be in the general interest. These groups believe that their advocacy will be of benefit to those far beyond their membership. They often engage in issues of civil rights, human rights, animal rights, and environmental issues, for example.

- The third type is governmental interest groups. Most countries have multiple layers of government. Within these layers are groups of actors with potentially competing interests. As policy insiders, these interest groups can be involved in every step of the policy cycle but are most influential in the policy formulation and policy decision making stages.

- The fourth type of interest group advocates on behalf of a single issue or cause. Similar to groups driven by narrow economic interests, these groups represent segments of society. However, the difference is that the goal of single-issue interest groups is non-economic.

A key distinction between types of interest groups are those that have privileged access to decision makers and the institutional agenda, or insider interest groups, and those that seek to influence public opinion and the systemic agenda, or outsider interest groups.

Insider interest groups include all those who are involved in consultation and negotiation with the government, often even before the government’s own view has crystallized. These groups, therefore, have privileged access points to the government and can exert influence throughout the policy cycle.

In contrast, ‘outsider’ interest groups lack these access points with the government. For some groups, this is deliberate, as they believe the close association with the government can delegitimate their actions. For other groups, they are more focused on influencing public opinion than they are influencing government. Still, others are too small or lack enough resources to motivate governments to build connections with them.

In the 2015 Canadian Federal election, the Liberal Party won a majority and Justin Trudeau became the 23rd Prime Minister of Canada. His predecessor, Stephen Harper, had been PM since 2006. Under the Government of Stephen Harper, the institutional agenda had shifted dramatically towards the West, towards limiting Federal power, and towards a much more circumscribed Canadian Foreign Policy. This meant promoting the energy sector, deregulating federal initiatives, cutting taxes, reforming the senate, and pulling back from the institutions of global governance. It is also meant quite an acrimonious relationship with environmental interest groups.

When Trudeau and the Liberals came to power, they shifted the government’s institutional agenda, notably on the environmental front. Soon after his victory, Trudeau promised to attend the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris, inviting all the provincial premiers to attend with him. He held a first ministers meeting on climate change within 90 days, both promising to help provinces with their own plans to meet national emissions reduction targets and threatening a carbon levy if they did not. He promised to phase out subsidies for the fossil fuel industry. Instead, the policy would shift towards establishing and supporting sustainable and clean energy sectors. More promises were made for protecting coastlines, national parks, and freshwater sources. Trudeau reached out to Indigenous peoples, promising to consult more transparently on projects that would impact their traditional lands.

This change in government opened an opportunity for environmental interest groups to move from the outside to the inside. The benefits of moving to the inside included more points of access and more influence with policy decision-makers. The cost of moving to the inside is the limits it places on interest groups for fear of losing their privileged access.

Glossary

Bounded rationality: is a common limitation placed on Rational Choice Theory. It suggests that when actors have limited time, limited information, or are acting through personal biases, they will act rationally even if they have not met the harsher conditions of RCT.

Budget-maximizing model: posits that civil servants would be more likely to pursue their own sectional interests than pursue the public interest in order to maximize their budget and the size of their department. They do this even to the detriment of the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the bureaucracy as a whole.

Collective action problems: describe a condition whereby all actors would benefit by cooperation but the cost of providing it is difficult or impossible for one person to provide alone and conflict between actors prohibits them working together to provide it.

Common good: is something that is of benefit for an entire community at the aggregate level.

Corporatism: is a more formalized relationship between the government and interest groups that institutionalizes the role of interest groups in the policymaking process.

Egotistically: is a focus on the interests and needs of one’s self or one’s in-group.

Elite theory: an extension of the Marxist theory argues elites represent a cohesive class-based interest group that is able.

‘Insider’ groups: are those interest groups with privileged access to the policymakers and are often involved in consultation and negotiation with the government on the institutional agenda.

Interest groups: groups constituted with the aim of promoting or shaping policies that they perceive to be of benefit to them, to society more generally, or to both.

Interests: are the agendas of single or collective agents which motivate action. This can be driven by self-interest or egotism. It can also be driven by public interest or other-regarding goals.

Market goods: those items, or commodities, that can easily be exchanged between private individuals.

‘Outsider’ group: are those interest groups that lack access to policymakers either by choice or by being denied by policymakers. They tend to exercise influence through the systemic agenda.

Pluralism: a theory of politics that argues in a liberal democracy power is or should be dispersed amongst a number of different interest groups.

Public goods: are those goods and services that are not easily profited upon, that society decides shouldn’t be exclusive to those who can afford it, and those goods and services which society seeks to regulate.

Public interest: is something that is of benefit for an entire community at the aggregate level.

Rational Choice Theory: seeks to quantitatively model what actors will do in any given context based upon the human capacity for instrumental reason.

Satisfice: to choose the first option that meets the needs of a problem or directive from above.

Self-interest: actions or policies to the benefit of an identifiable subset of society: a person, group, organization, or corporation.

The tragedy of the Commons: is a logic that suggests short term self-interest will lead to the depletion or degradation of common resources.

Trigger: is an event, decision, or circumstance that leads an actor to perceive an opportunity or threat to their interests and therefore motivate them to action.

Win-win situation: describes a situation whereby one’s self-interested action is also perceived to be in the interests of others or in the public interests.

Zero-sum game: describes a situation where progress or benefit to one actor comes at the expense of another actor.

References

Abedi, Maham. “SNC-Lavalin affair, explained: a look at remediation deals at the centre of the controversy”, Global News. March 6th, 2019

Anonymous. “2019 Trudeau Report Card”, iAffairs. March, 2018.

Bierce, A. The Devil's Dictionary. New York: Oxford University Press, 1911.

Blyth, M. 'Structures Do Not Come with an Instruction Sheet: Interests, Ideas and Progress in Political Science', Perspectives on Politics, I: 695-706. 2003

Cecco, Leyland. “Trudeau’s environmental record on the line in Canada election year”, The Guardian. January 2nd, 2019

Do, Trinh Theresa. “Justin Trudeau’s environment plan: End fossil Fuel subsidies, invest in clean tech”. CBC News, June 29th, 2015

Freeland, Chrystia. “The Rise of the New Global Elite”, The Atlantic. January/February, 2011.

Hardin, Garrett. Living within Limits: Ecology, Economics, and Population Taboos. 1995.

Htun, M. and Weldon, S.L. (2010) 'When Do Governments Promote Women's Rights? A Framework for the Comparative Analysis of Sex Equality Policy”, Perspectives on Politics, (1992) 8(1): 207-16.

Hunter, Adam. “Saskatchewan makes its legal case, arguing federal carbon tax is unconstitutional”, CBC News, February 12th, 2019.

Johnston, Jane. “Whose Interests? Why defining the ‘public interest’ is such a challenge”, The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/whose-interests-why-defining-the-public-interest-is-such-a-challenge-84278

Lewis, J. 'Gender and Development of Welfare Regimes', Journal of European Social Policy, (1992). 2(3): 159-73,

Libin, Kevin. “What the West Wants Next”, The National Post. October 28th, 2011.

Lindblom, C. Politics and Markets: The World's Politics-Economic Systems. New York: Basic Books, 1977.

Lukes, S. Power: A Radical View. London: Macmillan, 1974.

Macpherson, Alex. “Meewasin faces ‘profound cute’”, StarPhoenix. April 17th, 2019.

Meslin, Dave. “Why Bribery Still Works in Canadian Politics”, The Walrus. July 16th, 2019.

Niskanen, W. Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Chicago, IL: Adline, 1971.

Olson, M. The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1982.

Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Penner, Derrick. “Alberta launches last-minute 1$-million Trans-Mountain promotion in Vancouver”, Vancouver Sun. May 30th, 2019.

Smith, Gavin. “Support for Oil Tanker Moratorium Act has history on its side”, Policy Options. June 4th, 2019.

Struzik, Ed. “Canada’s Trudeau is under fire for his record on green issues”, YaleEnvironment360. January 19, 2017.

Vogel. D. National Styles of Regulation: Environmental Styles of Regulation: Environmental Policy in Great Britain and the United States. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1986.

Supplementary Resources

- Birkland, Thomas. An Introduction to the Policy Process: Theories, Concepts, and Models of Public Policy Making. 2011.

- Di Gioacchino, Debora, Ginebri, Sergio, and Sabani, Laura. The Role of Organized Interest Groups in Policy Making. Central Issues in Contemporary Economic Theory and Policy. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Hardin, Garrett, ProQuest, and ProQuest Ebook Central. Living within Limits: Ecology, Economics, and Population Taboos.

- Thomas, Clive. First World Interest Groups: A Comparative Perspective. 1993.

- Thornburn, Hugh G. "Interest Groups and Public Policy in Canada." Queen's Law Journal12, no. 3 (1988): 444-53.