Developed by:

Dr. Martin Gaal – University of Saskatchewan

Overview

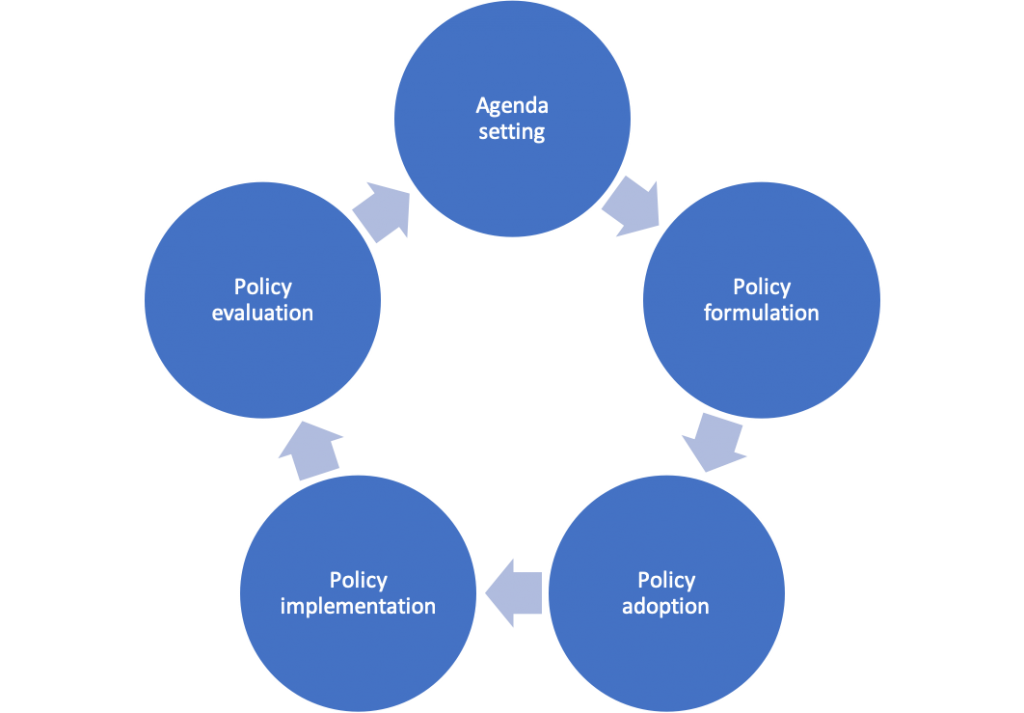

So far, we have focused on the frameworks of comparative public policy, including the three main clusters introduced so far: the policy cycle, the ideas/interests/institutions approach, and the Multiple Streams Approach.

In this module, we are going to examine how the processes of globalization have influenced comparative public policy analysis. Globalization is a contested term. The debate over what defines and constitutes globalization is about whether the economic, political, and social processes of globalization are something new and transformative in nature or whether they are simply a continuation of processes that stretch back hundreds if not thousands of years. This debate is important to the study of comparative public policy analysis. If the stronger narrative of globalization as transformation is true, then national policy making will be deeply constrained and international, and even supranational bodies will play a greater role. It also means that the logic of the market and competition will push policy makers in particular directions and constrain their ability to pursue robust social welfare programming. If the weaker narrative of globalization as constituted by age-old processes is true, then policymakers will adapt as they always have.

To understand the impact of globalization on public policy making, we will examine it through the frameworks of public policy so far introduced. We will then close with an examination of the two most direct consequences of globalization on public policy making, the increase in the trade of commodities and the rise of the investment capital. From this discussion, it is important to recognize that globalization has shaped and will continue to shape public policymaking.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Articulate definitions for globalization that are informed by the following perspectives:

- hyper-globalization vs. globalization skepticism,

- globalism vs. regionalism, and

- the differing impacts of globalization on developed states and developing states.

- Identify the impact of global issues and processes (i.e., globalization) on public policy.

- Adapt the policy cycle in the context of globalization to policymaking, most notably in the agenda setting and policy formulation stages.

- Adapt the role of ideas, interests, and institutions in policymaking in the context of globalization

- Adapt the MSA approach to policymaking in the context of globalization

- Apply comparative public policy analysis in the context of globalization.

- Globalization

- Outsourcing

- Hyper-globalization vs. Globalization skeptics

- Globalization vs. Regionalism

- Developed states, Developing states

- Global North, Global South

- Multinational corporations (MNCs)

- Non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

- International governmental institutions (IGOs)

- Trade of commodities

- Investment capital

- Social Progress Index (SPI)

- Trade-in services

- Foreign direct investment (FDI)

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

Hay, Colin, (2008). “Globalization and Public Policy” in The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy, Michael Moran, Marin Rein & Robert E. Goodin (Eds), (pp. 587-604). Oxford University Press. [See file in Canvas]

Stiglitz, Joseph E., (2016) “Globalization and its New Discontents.” Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/globalization-new-discontents-by-joseph-e–stiglitz-2016-08 [Online; for Learning Activity 7-1]

K.N.C., (2019). “Globalisation is dead and we need to invent a new world order.” The Economist. https://www.economist.com/open-future/2019/06/28/globalisation-is-dead-and-we-need-to-invent-a-new-world-order [Online; for Learning Activity 7-2]

Green, Michael, (2015). “Why we shouldn’t judge a country by its GDP.” Ideas.TED.com. https://ideas.ted.com/why-we-shouldnt-judge-a-country-by-its-gdp/ [Online; for Learning Activity 7-4]

Learning Material

Introduction

Figure 7-1: Danville. Source: https://flic.kr/p/4hAEZA Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Joe Lewis.

On the banks of the slow-moving Dan River, just near the northern border of North Carolina in the American state of Virginia, lies the sleepy city of Danville. Historically, tobacco farming and a thriving textile industry supported Danville’s local economy, but the city has been in a steady decline since the turn of the 21st century. The city’s story is familiar to many small cities in North America. The textile mill that had employed so many found that it could not compete on a global market – by 2004, it declared bankruptcy. The loss of this major industry hurt Danville. In 2009, the unemployment rate in the city was 15%. Many who could not find work moved away, and the population of the small city stagnated and began to decline.

However, in the past few years, Danville has been faring better. Solar panel farms built by the municipal-owned Danville Utilities have sprouted up around the city, supplying around 20% of its energy needs. The solar panels are part of a broader policy strategy pursued by the city, one that combines lower tax incentives for bringing in development in the downtown with the promise of renewable energy for attracting tech companies or similar industries to Danville. So far, the situation seems to be improving, as the unemployment rate is down to 5%. The downtown of Danville, once increasingly empty, now has new restaurants and breweries.

Why did Danville fall on hard times? What set of conditions led to this? How did these conditions influence the public policy pursued by local actors? Why did they choose the policies they did? How does the story of Danville compare to other small cities facing similar dilemmas? Were similar or different policies enacted? Were the outcomes better or worse? Why?

The story of Danville’s economic decline and a set of public policy decisions that seemingly helped to bring about recovery is a story that underlines several of the critical points that we will cover in this module – the relationship that comparative public policy has with the concept of globalization. Of course, this is only one side of the story. Thomas Friedman argues that globalization has played a levelling effect on the international economic order. The growing interconnectedness of economies abetted by advancement in technology and transportation have resulted in truly global supply chains and the rise of outsourcing. This, in turn, has led to more people involved in the market, an increase in developing countries economic output, an increase in the number of goods available at a sharply lower price, and, most significantly, a drastic decrease in extreme global poverty, albeit with an increase in inequality. Therefore, while Danville tells one side of the story, so does the rise of the call-center industry in Bangalore, India, or the rise of Shenzen, China, as a workshop to the world.

However, in this module, we will be focusing on the first narrative: how policy decisionmakers in the developed world have been confronted by and responded to the impact of globalization. As we will see, there is an ongoing tension between globalization and the entire idea of “public policy.” Although hard to define, typically, globalization involves the breaking down of barriers that have long existed between countries in the world and an increased level of interdependence between countries as a result. The breaking down of these barriers means that the local, embedded character of the “public” expands to include the entire world – and that those crafting policies have to contend with factors beyond their control.

Before moving on, read the article by Joseph Stiglitz (also listed in the Required Readings section of this module):

- “Globalization and its New Discontents”, Project Syndicate, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/globalization-new-discontents-by-joseph-e–stiglitz-2016-08

On the following Padlet board, add a post with your answers to the following two questions:

- Do you think the processes of globalization are of benefit to Canadians?

- What do you think are the main complications that globalization had created for Canadian policymakers?

On this board, you can also “upvote” / “downvote” or comment on posts that you agree or disagree with.

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include:

- Your Padlet contribution

- The Padlet contribution by one of your classmates and why you think this is a strong contribution

Globalization: Definitions and Perspectives

Before we can tackle what impact globalization has on public policy, we first need some conceptual clarity. Take a moment to consider your current understanding of that concept: how do you define globalization?

- Perhaps you think of globalization in cultural terms, as the spread, consumption, and cross-pollination of different cultural exports around the world. You might imagine a consumer in North America eagerly listening to K-Pop as an example of this. Or the global export of Hollywood movies and the rise of new sites of cultural production like Bollywood.

- Perhaps you think of globalization in economic terms, recognizing the extent to which countries rely on exports and imports for their GDP, driving a reduction in trade barriers. This becomes abundantly clear if you think of the supply chain behind much of what you buy, from the food you eat and the clothes you wear to the electronics you use to do your coursework and stay in touch with friends and family. Each of these objects, or at least their components, have likely travelled thousands of kilometres before you bought them. Another example might include the increasingly rapid flow of financial capital, with the image of stock exchanges and traders working around the clock, from Toronto to New York, London, Bombay, Shanghai, Tokyo, and Toronto.

- Perhaps you view globalization as primarily political, and see the influence of international governing bodies like the United Nations, or global international economic institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as examples of globalization.

Perhaps you define globalization as a combination of all these elements, or only a few. If you find it challenging to settle on a definition, you are in good company – as precisely defining globalization is a matter of contention in academic literature.

Figure 7-2: Globalization. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/technology-network-digital-4085029/ Permission:CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of TheDigitalArtist.

Hyper-Globalization vs. Globalization Skepticism

Figure 7-3: Hyper-globalization, or globalization skepticism? Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/community-one-world-connection-4848326/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of TheDigitalArtist.

The problem of definition carries into the ongoing scholarly disagreement about globalization, and this, in turn, complicates policymaking. To what extent, if any, is globalization occurring or has occurred? To what degree is the current form of globalization new? Or is contemporary globalization an evolution of systems and practices rooted as far back as the Chinese Silk Road in 114 BC? And depending on how you answer these questions, how can/should policymakers respond? When we look at the discussion in scholarly communities, we can broadly define two different groups regarding globalization:

On the one side, there is the strongest thesis labelled hyper-globalization, which argues we are experiencing the fundamental transformation of our global economic, political, institutional, and social structures. They claim we are witnessing a period of unprecedented revolution where the state is becoming anachronistic, that citizenship is less meaningful, and that the foreign and domestic division has less substance. If this is the case, what are the implications of policymaking? How does this shift the locus of decision making? What new actors are involved? How are traditional actors constrained?

On the other side, the ‘globalization skeptics‘ believe globalization is simply an intensification of long-running global processes. They argue that the current movement of goods, money, and people around the world is no different in function than that of the ancient Chinese Silk Road – it is simply a matter of scale. If this is the case, how has this shift in scale changed the process of policymaking? What new variables are involved? How have actors been empowered or constrained?

The vast difference between the two groups is, in no small part, explained by the different definitions of globalization they are using. This results in a situation where the hyper-globalists and skeptics look at the same data and reach different conclusions regarding the form and function of globalization.

Figure 7-4: Hyper-globalists and skeptics look at the same data and reach different conclusions regarding the form and function of globalization. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/question-mark-note-continents-earth-2153518/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Some define globalization as the extent to which the global market is open and integrated between countries. The hyper-globalists see entrenched supply chains and free moving capital as an example of how contemporary globalization is unprecedented. Yet, the global market is neither entirely open nor perfectly integrated. Moreover, it is unclear how open and integrated the global market needs to be to fit this definition of globalization. If we define globalized trade as the amount of a country’s GDP that it exports and imports, globalization has indeed increased significantly. Yet if we compare the degree of regulation applied to the international movement of goods, labour, and finance today to the period prior to the First World War, we would see that today there is less free movement than in that period. Does that mean the world was globalized then, but not now? Or is it a question of using the modifiers’ more’ and ‘less’ to explain degrees of globalization? Are we less globalized now than we were in 1900? Or is this a flawed comparison?

Globalization vs. Regionalism

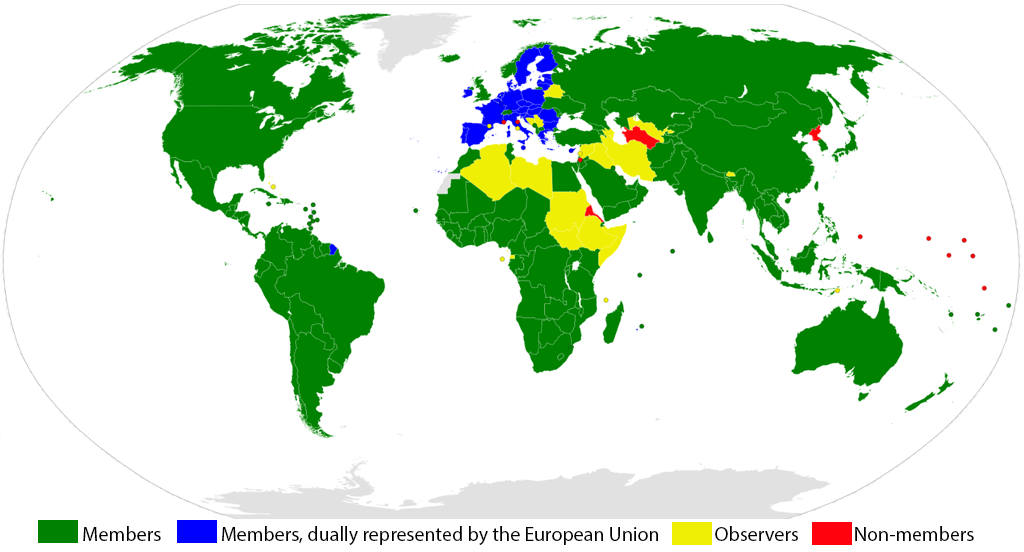

Figure 7-5: Map of the European Union member states. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Global_European_Union.svg#/media/File:Global_European_Union.svg Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of S. Solberg J.

Another strategy for defining and measuring globalization is to contrast its defining elements with an opposing, more local orientation. For instance, we can contrast regionalism against globalism. Hyper-globalists often use increased trade as evidence of globalization. They point to the increasingly globalized supply chains whereby goods are sourced, manufactured, and marketed in several states before being sold to the end consumer. Further, hyper-globalists would simply point to your local grocery store or Amazon’s website, where you can buy almost anything at any time of the year. There is no such thing as a ‘seasonal good’ anymore. However, increased trade between countries does not necessarily provide evidence of increased globalization per se if we are referring to trade that extends globally. Much of this trade is happening within much more limited regions. The most significant increase in cross-border trading is happening in regional blocks like the European Union or the North American Free Trade Area (which may soon be replaced with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement). With this distinction, the question is: is this globalization or regionalization?

The question of whether we are experiencing globalization or regionalization is essential for both understanding the phenomena but also for public policy. Regionalism has many of the features present in definitions of globalization, such as the lowering of barriers to the movement of goods, people, ideas, and capital between countries and the development of intergovernmental organizations to manage these processes. However, the critical difference is that regionalism limits these features to a particular geographical region and amongst individual member states. Consequently, regionalism is much less transformative since the members of a region have more features in common and require less drastic steps to harmonize their economies or institutions. With regionalism, countries compete with the other more alike states, while globalization means they compete with states worldwide.

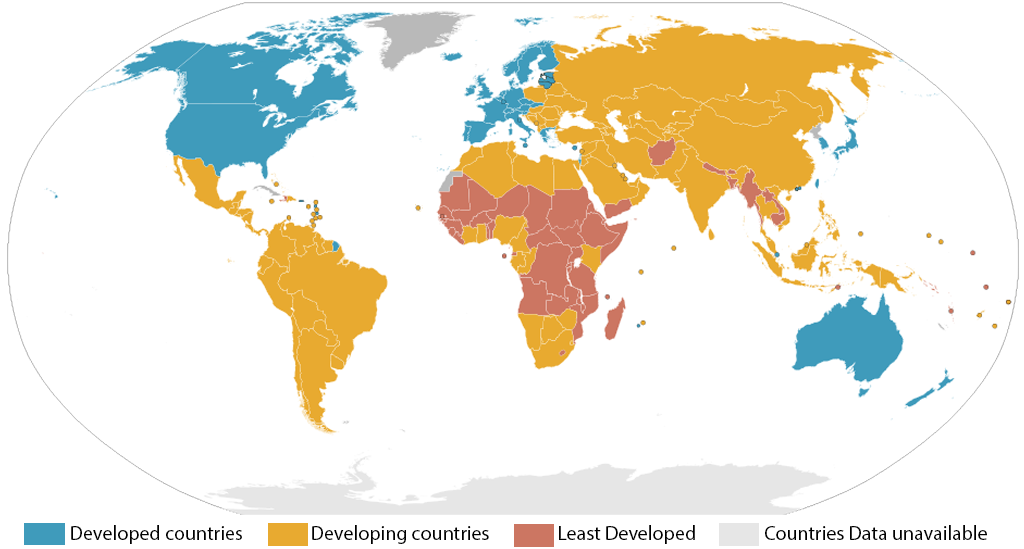

Globalization in Developed States vs. Developing States

Another oppositional comparison that has utility in defining globalization is the distinction between its form, function, and impact in the most economically developed states versus economically developing states. The narrative of globalization, especially for the hyper-globalists, focuses on the reduction of barriers between states. There is a sense that this is happening to all states everywhere, relatively equally, and with similar effects. It is a story of how free trade purportedly helps all states by lowering costs, increasing competitiveness, increasing the quantity/quality of goods available to a state’s citizens, and increasing prosperity. There is support for this thesis. A greater quantity and quality of goods are available to consumers at a lower price than ever before. There has been a drastic drop in absolute poverty around the world. However, the skeptics argue that lowering barriers between states is not universal, nor is it equal. Trade barriers often protect local industries from foreign firms that threaten their viability, and such protectionism is particularly evident in the most economically developed states. These states use their privileged position in the global economic and political order to make sure barriers to competition are maintained or even enhanced. However, this is less of an option for more vulnerable states, especially those that find themselves needing support from the international financial institutions, like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Such states are often forced to reduce barriers as a condition of receiving loans. Therefore, some skeptics argue globalization is simply a set of policies enacted in the interest of those at the top of the social, economic, and political hierarchies. From this perspective, globalization is nothing more than another means for the rich and the powerful to extract wealth from everyone else. It is a new way to accomplish a perennial desire – greed. This argument is augmented by the more recent reversal in the narrative of who benefits under globalization.

Figure 7-6: Map of the world’s countries as designated by the International Monetary Fund in the April 2009 World Economic Outlook. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Imf-advanced-un-least-developed-2008.svg#/media/File:Imf-advanced-un-least-developed-2008.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

While wages in many industrialized countries in the Global North have stagnated, wages and living standards have increased in the Global South. In the mid-20th century, what was good for Ford Motor Company was good for America. Companies were an expression of national values and national interests. They hired American workers and invested in American cities. But if your car is designed in one country, marketed in another country, manufactured in a third country, and includes parts and materials sourced from dozens of others, how ‘American’ is Ford? If Ford deposits its profits in low-tax jurisdictions to avoid taxes, how in sync are Ford’s and American interests? Multinational corporations (MNCs) have increasingly become deterritorialized, with corporate headquarters making decisions based on profit instead of aligning with the national interest. Traditionally this was keenly seen by the exploitation of labour in the Global South and often with the support of decision makers in the Global North. However, more recently, MNCs have used the threat of leaving the Global North to undermine labour standards and other regulations in the name of profit. This, in turn, has created increasing resentment and pushback from labour groups in the Global North.

Perspectives of Public Policymaking

However, whether the hyper-globalist or skeptics are right, globalization plays a significant role in public policymaking and offers more entry points for comparative public policy analysis. If the hyper-globalization theory is correct, public policymaking will, by necessity, become much more complicated, much less independent and much less local. Instead, effective policymaking will require highly trained experts or ‘technocrats’ that can navigate the increasing interdependence of public policy at a global level. This poses a threat of democratic deficiency in policymaking, but this might be an unavoidable trade-off – one can either have a policy that is efficient and effective within the global system but undemocratic, or have a policy that is democratic but inefficient and ineffective.

On the other hand, the skeptics would argue that while globalization does complicate public policymaking, it is more about scale than transformation. From this view, effective and efficient public policy might require talented decisionmakers. However, the national and local interests will, or (perhaps more normatively put, should), still drive their goals and negotiations.

If you haven’t already, read the Economist article (also listed in the Required Readings section of this module):

- “Globalisation is dead and we need to invent a new world order”, The Economist, https://www.economist.com/open-future/2019/06/28/globalisation-is-dead-and-we-need-to-invent-a-new-world-order

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- What does Mr. Sullivan argue are the side effects of globalization? What policy dilemmas does this create?

- What are the ‘levellers’ and the ‘leviathans’? Why does Mr. Sullivan argue they are significant for understanding the next phase of globalization?

- How will this debate affect policy making in the future?

The Global Dimension of Comparative Public Policy

The clearest way to see the global dimension of public policy is to look at it through the lenses of policymaking we have so far introduced:

- the policy cycle;

- the role of ideas, interests, and institutions; and

- the Multiple Streams Approach.

We will then conclude with a look at how globalization opens comparative elements to public policy analysis.

The Policy Cycle

Figure 7-7: Five stages of the policy cycle. Permission: Courtesy of the Distance Education Unit (DEU) and the Department of Drama, University of Saskatchewan, based on https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Knill-and-Tolsun-five-stages-of-the-policy-cycle_fig4_242347923

If we apply the logic of globalization to the policy cycle, we can see how it makes the process of policymaking much more complicated, most notably in the agenda-setting, policy formulation, and policy evaluation stages.

Agenda Setting

In Module 1, we introduced agenda setting as part of the policy cycle and noted the distinction between the public/systemic agenda and the institutional agenda. Globalization expands the scope of both. For the public/systemic agenda, globalization widens the horizon of threats and opportunities that confront policymakers. For example, let us look at the debate over Indigenous rights. From a domestic approach, Indigenous rights for the Canadian government is an issue contextualized and localized to Canadian politics. It is about issues such as the Indian Act, the impact of the Residential Schools System, or access to clean drinking water, to name just a few outstanding issues. These are all issues on the public agenda that Canadian and Indigenous policymakers can act on with the resources at hand. But if we broaden the public agenda to the global level, it would include the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and, more generally, the experiences shared by Indigenous peoples under a global system of settler colonialism. The systemic level complicates policymaking by creating new demands from new audiences advocating for governmental action.

In the same vein, globalization also broadens the institutional agenda. Decisionmakers have to be more keenly aware of threats and opportunities both at home and abroad. For example, while the federal or a provincial government may seek to support the local economy, they must factor in the decisions being made in Washington, Brussels, Beijing, and the many international organizations that impact the global economy. More specifically, think of the spurious decision by American President Trump to impose tariffs on Canadian aluminum in 2018 or of Chinese President Xi to ban Canadian soya beans, canola, pork, and beef in retaliation for the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in 2019. Or think of the competitive disadvantage that the Canadian manufacturing sector faces with states in the Global South due to policies that increase regulatory and labour costs. Economic policies become even more complicated by MNCs who have become increasingly deterritorialized, creating a new quasi-independent actor to contend with. And these MNCs can challenge all but the wealthiest of states in terms of revenue generation. For example, in comparing states and MNCs, Walmart is the 9th-largest wealth generator, just after Canada. Beyond economic policies, globalization has created a need for international cooperation in both functional policy areas and security concerns. Functional policy areas include coordinating technology, like the internet, global health threats, like pandemics, and economic rules, like finance, banking, or investments. Security issues include the increasingly interdependent nature of organized crime, terrorism, climate change, and protection of cultural practices. These new international policy issues clamour for attention with the traditional policy issues on both states’ systemic and institutional agendas.

Finally, globalization complicates the agenda-setting stage by adding a transnational level that exerts an independent influence beyond the borders of sovereign states. International organizations such as the UN, the WTO, and the World Bank are powerful actors in determining policy. While constituted by state representatives, these institutions often develop a quasi-independent identity, pushing policy prescriptions that conform to their worldviews and interests. Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) advocate for civil society interests. MNCs also advocate for their more narrowly defined interests. Thus the autonomy of the traditional state in agenda-setting has become increasingly constrained, and aspects of policymaking have become detached from locally controlled structures. Therefore, globalization significantly complicates the agenda-setting by broadening both the systemic and the institutional agendas.

Policy Formulation

However, while globalization may broaden and complicate the agenda-setting stage of the policy cycle, it also puts limitations on the policy formulation stage. While, in the most general sense, policymakers are seeking to address perceived threats and opportunities to the security and prosperity of their constituents, globalization limits their arsenal of policy instruments both for policy formulation and evaluation.

In terms of policy formulation, globalization places constraints on policymakers. Policymakers need to remain competitive in a globalized world that makes policymakers wary or insecure about policies that increase the tax and/or regulatory burden on corporations, especially MNCs. If the government raises the tax and/or regulatory burden on a sector of the economy, corporations may relocate their economic activity, slow down their production, or find another cost-cutting measure such as automation. Such decisions may, in turn, increase unemployment and stress welfare provisions. As an added consequence, low levels of taxation means the very capacity to enact public policy is also constrained. This functions as a pervasive idea – it is typically supported by the informed knowledge of experts that policy needs to adhere to the interests of capital if that particular state has any hope of attracting and maintaining capital investment. Without said capital investment, a city, country, or sub-state region can expect economic stagnation and decline. Globalization, therefore, exerts two competing impulses on decisionmakers. On the one hand, policymakers feel a need to accommodate the interests of global capital, and on the other hand, they need to extract sufficient resources to support welfare provisions.

Second, globalization increasingly constrains policy formulation by agreements made to combat global problems like the environment, organized crime, and economic stability. These agreements create obligations, albeit weaker than domestic law, that limit policymakers’ ability to formulate policy responses. For example, the Paris Climate Agreement has set expectations for state parties to commit to targeted CO2 emissions; for Canada, that means cutting emissions by 30% from 2005 levels. Canada’s commitments under the Paris Agreement limit policy options for economic activity and have resulted in the contentious implementation of a carbon pricing policy in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and New Brunswick.

Policy Evaluation

International commitments also make policy evaluation more complicated as it adds another metric to assess. For example, when approving new pipelines or resource extraction projects, the government must be cognizant of how this will impact their international commitments like those agreed to in the Paris Climate Agreement. On the other hand, in a comparative sense, globalization also opens new policy options by providing the ability to compare policy contexts and policy choices with other jurisdictions. For example, can both the Provincial and Federal governments find solutions in a hybrid carbon pricing plan, like that of Switzerland, where a tax is combined with a cap and trade system?

The Role of Ideas, Interests, and Institutions

The role of ideas, interests, and institutions in policymaking also has a global dimension.

Ideas

Figure 7-8: Ideas. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/idea-world-pen-eraser-paper-1880978/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of qimono.

At the strongest end of the globalization thesis, the hyper-globalists argue that the world has transformed. They claim the sovereign state is anachronistic and that borders no longer contain that policy. However, is such a proposition based on a material change or ideational change? The border between Canada and the US has not moved or become more porous. But, the ideas that shape decisionmakers’ views have changed. Their cognitive paradigms have shifted to see policymaking in a more global context, with more actors and opportunities and threats. This, in turn, has moved the normative framework of policymakers who have come to see the need to accommodate global capital and protect against global threats such as transnational terrorism or organized crime. Much of this has solidified in a world culture that sees an interdependent world, with goods, capital, and labour moving more globally, albeit not equally nor equitably. For those policymakers who see globalization as a positive force, these ideas are used to frame the opportunities of global processes and create programmatic platforms. And vice versa for those who see globalization as a threat.

It is important to note that these ideas are also intrinsically comparative. Those that see globalization positively will look to how others have managed to capitalize on the opportunities presented. For example, the success of the Bangalore call center culture in India has been replicated and even surpassed by Manila in the Philippines. And those who see globalization as a threat will do the same. For example, the Brexit movement in the UK has been recognized as a leader in pushing back against threats to state sovereignty and has bred imitations, such as the Wexit movement in Alberta, which has threatened secession.

In each case, the ‘ideas’ of what is possible and normatively good has shifted. Even the skeptics, who question the idea that globalization is transformative, recognize the ideational role that the narrative of globalization has played on how we see the world and how we see policymaking.

Interests

Figure 7-9: Interests. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/new-york-globe-skyscraper-blue-sky-2088958/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of qeralt.

As discussed in Module 4, ideas may shape what an actor believes to be true or appropriate, but it is often interests that motivate actors to try and shape public policy. Globalization has created or at least given voice to new actors with their own interests. Most notably, economic globalization has created MNCs that are so large and influential they challenge many states’ resources. As previously mentioned, Walmart is only slightly smaller than Canada in a ranking of the largest states and MNCs. Moreover, these MNCs are each narrowly focused on a specific economic activity and, therefore, with particular policy interests. For example, Royal Dutch Shell is the world’s third-largest company with nearly 400 billion dollars in revenue. UnitedHealth is the largest for-profit health care company in the US, with 226 billion dollars in revenue. Exor is a financial holding company that had 175 billion dollars in revenue. With such massive revenue streams, MNCs have a keen interest in influencing policymaking. Global environmental policy will potentially profoundly influence the bottom line of resource extraction, manufacturing, and retail MNCs. The same holds true for every other sector, from finance and trade to pharmaceuticals and manufacturing.

Another group of actors enabled by globalization are NGOs, which largely advocate for civil society on social and political issues – for example, OXFAM advocates for global poverty reduction. Save the Children advocates for kids caught in war zones like the Syrian conflict and the dangers they face through irregular migration. World Wildlife Federation (WWF) advocates for nature conservation and biodiversity. While much more limited in terms of resources, NGOs play an essential role in checking the interests of MNCs and states. Again, there is an intrinsic comparative element in the pursuit of interests as each actor will seek and adapt strategies that have worked for other actors.

Institutions

Globalization also has impacted the institutional level of policymaking. Most formally, it has added an international layer to the policymaking context through decision making institutions; for example, the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. These institutions act as platforms through which international law, international regimes, and international norms are agreed to, are monitored, and, if possible/necessary, are enforced.

The UN General Assembly arguably represents global public opinion, establishing important guiding normative principles through such agreements as the UN Declaration of Human Rights (UNDHR 1948), the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW 1979), the Rights of the Child (1989), and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP 2007). While it is often difficult to enforce these agreements, they do constrain or enable policymaking, most often by shaming decisionmakers that breach established norms.

The WTO is the most supranational of all the International Governmental Institutions (IGOs), in that it negotiates the rules of international trade and enforces those rules through a binding dispute settlement body. The binding nature of the WTO Dispute Settlement Body imposes even stronger constraints on decisionmakers.

Further, these formal institutions create more informal institutions that dictate expectations of behaviour. For example, there is an expectation that states should respect the human rights of their citizens. This has evolved into the Responsibility to Protect agreement, which posits a states’ sovereignty is conditional on protecting its citizenry from gross human rights violations. There are normative expectations on gender equality as well as children’s and Indigenous rights. This adds complexity and constraints to policymaking as actors contend with both domestic and international demands.

Comparative public policy plays an important role here. As citizens, corporations, and civil society actors advocate for their preferred policy outcomes, they will often use the adherence or breach of informal institutions as part of their argument. For example, when Canada refused to ratify the UNDRIP, both domestic and international NGOs sought to pressure the Canadian government by pointing out how this decision ran counter to established global normative institutions.

Figure 7-10: Map of World Trade Organization members and observers. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WTO_members_and_observers.svg#/media/File:WTO_members_and_observers.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Danlaycock.

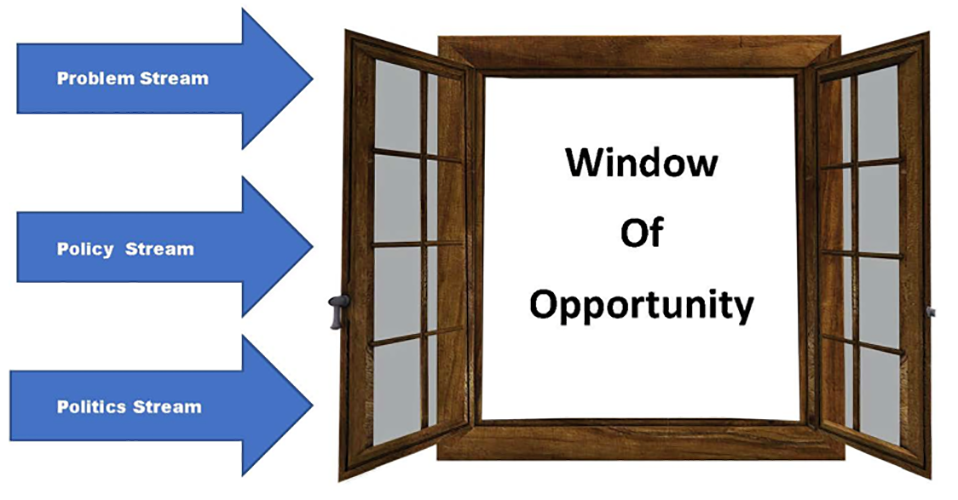

The Multiple Streams Approach

Finally, we want to assess the role of globalization in policymaking through the lens of the Multiple Streams Approach (MSA). The MSA argues that policymaking requires the convergence of the three following conditions:

- an identified problem (the problem stream),

- a viable solution (the policy stream), and

- the political will to implement it (the politics stream).

Figure 7-11: The Multiple Streams Approach (MSA) and the Policy Window. Permission: Courtesy of course author Martin Gaal, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan, based on https://pixabay.com/illustrations/window-open-window-glass-outlook-1798492/

As introduced above, globalization forces policymakers to confront new issues. Most explicitly, the globalization of trade, finance, and services has created problems for national decisionmakers. They must contend with the interests of MNCs as well as with the interests of their domestic constituents. They must balance the need to be globally competitive with supporting the welfare provisions that protect citizens and allow them to actualize their potential. The processes of globalization have also created a demand for decisionmakers to coordinate and cooperate on international issues that pose a threat to their security or prosperity. Some of these issues are functional in nature, for example, coordinating standards and procedures for international telecommunications and the internet or regulating air traffic and satellites. Other issues require political agreement, like combatting global climate change or the ever-sophisticated nature of international crime syndicates. And still other issues are more immediate security threats, such as international terrorism or war, and require a more expedient and perhaps ad hoc response.

To facilitate coordination and cooperation on these global issues, states have created both formal and informal institutions. As well, NGOs and MNCs have created advocacy groups and networks to defend their respective interests. This milieu of states, institutions, MNCs, and NGOs constitutes much of the global policy stream, generating many potential policy responses. For example, in 2008, when the US sub-prime mortgage crisis went global, threatening to create an economic depression on par with the Great Depression of the 1930s. This Global Financial Crisis was particularly problematic, having originated in the US. The US is not only the world’s largest state economy, but the American dollar and American institutions are core to the functioning of the global economy. States, institutions, MNCs, and NGOs all suggested appropriate policy responses:

- At the state level, governments sought to mitigate the localized effect of the crisis and avoid contagion from the US.

- At the institutional level, the IMF, the World Bank, the WTO, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the World Economic Forum all advocated for policy responses that would mitigate what they saw as the most critical ramifications of the crisis.

- NGOs responded with some urgency as they saw both the direct risk the financial crisis posed to the world’s most vulnerable populations as well as the prospect of the world’s developed economies pulling back from their global commitments to addressing poverty, development, and environmental protection.

While many potential policy solutions exist to policy problems on the systemic and/or institutional agenda, the MSA approach argues policymaking only happens when a policy window opens. This policy window appears when there is sustained attention to a problem, an identified and feasible policy response, and sufficient political will to carry it through. This is the same for domestic policymaking as it is for responding to global issues. However, globalization does complicate the process. Decisionmakers are confronted with a much broader range of policy problems, many of which might be beyond their scope to handle. They are faced with a much broader range of policy solutions as NGOs, MNCs, and IGOs, all advocate for their particular interests. They are confronted with a more diverse set of demands by constituents who may perceive the processes of globalization differently from each other. In the case of the 2008 financial crisis, there was undoubtedly sustained attention to the problem. There was a broad range of policy responses, and there was the political will to act. While there was variance in how states responded, there were broad similarities. States sought to stimulate the economy by lowering interest rates and increasing government spending. They sought to boost confidence in the economy and to avoid mass unemployment by underwriting debt and taking ownership stakes in large companies at risk of bankruptcy. Many, but not all, states reinforced regulations and strengthened oversight capacity.

From a comparative perspective, the application of the MSA to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis is interesting. It is interesting to see why so many states adopted similar policy responses. It is interesting to see why some states, most notably Iceland, responded with much more robust policy responses, including the nationalization of the three largest banks and the successful prosecution of both senior banking officials. It is interesting to see why systemic change was possible in 2008 when the developed economies were at risk, but not in 1997 during the Asian Financial Crisis or the Latin American Debt Crisis in the 1980s. From the MSA approach, many of these differences can be explained, at least in part, by the problem stream and policy stream. However, the most convincing explanations can be found in the last stream defined by political will. When the wealthiest countries were under threat, systemic change was possible. It became a faulty system and not the policies of the states affected, unlike in 1997, when it was the fault of South Korea or Thailand, and unlike the 1980s when it was the fault of Mexico or Argentina. In these earlier cases, it was argued that states needed to be disciplined by the market. In 2008, it was claimed the system needed to be reformed. The MSA offers fruitful avenues to explore these particular outcomes.

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal, related to the public policy issue that you have chosen to cover in your Podcast and Policy Brief assignments:

While many public policy issues are seen as ‘domestic’ in nature, most if not all are increasingly influenced by global actors, institutions, and/or processes.

- How does globalization influence the approaches of comparative public policy analysis as applied to your research topic?

Case Study: Increased Trade of Commodities & Flow of Investment Capital

Regardless of the definitional debates, globalization is an increasingly important constraint on public policymaking. Globalization introduces new constraints and opportunities for policymakers. The examples of Danville and Bangalore introduced earlier highlight this: the former was hit hard by the move towards global supply chains while the latter capitalized on these same processes. However, more recently, Bangalore has had to adjust as cities like Danville have adapted to changing circumstances and new, hungrier challengers emerge, like Manila. The role of globalization in policymaking is complex. We could look at the role of the WTO in lowering trade barriers. We could look at the coercive role of global capital and MNCs continually seeking to reduce the cost of resources, labour, and taxes. We could look at the role of IGOs, NGOs, MNCs, and states in shaping the norms of the international political economy. However, to wrap up this module, we look at the two most basic and most influential processes of globalization on public policy making: the increased trade of commodities and the increased flow of investment capital.

Increased Trade of Commodities

Figure 7-12: Commodities. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/world-packages-transportation-4292933/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of AbsolutVision.

The increased trade of commodities is due mainly to the sharp reduction of the barriers to trade that began with the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947 and was continued with the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. The victors of World War II believed that the conflict was, in part, fomented by global economic strife. In response, they created the Bretton Woods Institutions to manage currency valuations, provide emergency financial support to states who ran into liquidity crises and reduce trade barriers. The GATT was responsible for this last goal, the liberalization of trade, and was largely successful, with average tariff rates dropping from an average of 22% in 1947 to less than 5% when the WTO took over. This reduction in tariff and non-tariff barriers meant there was increased mobility of goods. In dollar value, this translated into a shift from nearly 62 billion US dollars in global trade goods in 1950 to nearly 4 trillion US dollars in 1995. By 2018, the value of trade goods had reached 19.5 trillion US dollars due to the internalization of the global market idea and innovation in technology, transportation, and supply chains. This, in turn, meant that policymakers must account for the need to be more economically competitive since local firms would have to compete on a global level.

If we compare today to the post-World War II economic situation, we can see the force of this imperative in action. In the post-war economic boom, closed national economies primarily relied on domestic production and goods consumption. The Keynesian economic policy effectively controlled this. But in a new globalized world, increased demand for goods produced elsewhere increases imports. Those commodities produced within a country must now compete in a global market with other producers. Competitiveness now became a core policy concern – the ability to produce and sell a commodity on the international market less than other producers. Anything that increases the cost of production reduces competitiveness and, therefore, carries potential costs. This created downward pressure on wages to reduce labour costs. It put pressure on governments to slash regulations to facilitate cheaper production. It put pressure on governments to cut corporate taxes to ensure the retention of jobs, especially manufacturing jobs and even more, especially those with MNCs who had facilities in other places. This created a ‘race to the bottom mentality’ that was particularly influential with policymakers unfamiliar with competition and abetted by investors who demanded quarterly returns on their investment. This is a narrative that should be familiar to anyone looking at the history of the shifting policies from the post-war western countries into the present.

However, the simplicity of the logic here does not neatly map out onto reality. Many countries that are very open regarding trade, as measured by the degree to which imports/exports drive their GDP, have large public sectors. For example, many European countries, particularly the Nordic states, are very trade-dependent and have large governments and strong welfare provisions. This should not be the case if the constraining power of globalization to enhance competitiveness was all-powerful. However, as Michael Green has argued, the study of comparative public policy may offer some interesting insight here. He uses the Social Progress Index (SPI), which measures the quality of life, to demonstrate that how a state responds to the opportunities and threats presented by globalized trade is, to no small degree, a function of policy entrepreneurship. When comparing big countries with small countries and rich countries with developing countries, there is a degree of variance from what is expected. It is expected that rich and large countries are better situated to take advantage of the process of globalization and the opening of their borders to a greater flow of goods. And to a degree, this holds true – larger and richer states have gotten larger and richer according to GDP. But if we instead look at the SPI, we find that some smaller states do better than larger states and some developing states do better than wealthier states. This suggests that the benefits and costs of globalization more generally, and the increased trade of commodities more specifically, can be addressed through policy ingenuity. This further indicates that studying what other policymakers are doing in other jurisdictions is not only prudent in positioning one’s own constituency, but it suggests that policymakers can and arguably must learn from what others are doing.

Investment Capital

Closely related to the notion of the economic integration of countries through increased trade of commodities is the idea of the mobility of capital. In the last section, we mentioned that the GATT became the WTO in 1995. To a large part, this reflects the limitations of the GATT, which was concerned with the trade of physical goods. The WTO recognizes the increased role of trade in finance and services. Today, some countries, like the UK (45%) or the Bahamas (87%), are increasingly reliant on the trade-in services as a percentage of GDP. Trade-in services have grown by more than 10% per year since 2000, and in 2017 was worth 13.3 trillion dollars. However, all of this is dwarfed by the flow of international finance. International finance includes the financial markets, including currency trading, foreign direct investment. As an example, every day, there is an average of 5 trillion dollars that turnover in the currency market alone. That means in three days, the currency market moves more money than the yearly trade in services, and in eight days, it moves more than both the trade in goods and services. This has deep implications for policymaking in that there is a need to account for the power of the market and take stock of the market mentality. However, we will focus on a more concrete concept of international finance, foreign direct investment (FDI).

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is the act of using one’s economic resources in another state for the purpose of economic activity. For example, an MNC may open a factory in another country to access resources, like gold or oil. They may also be looking for the benefits of cheaper labour, as the Bangalore call center. Or they may be trying to gain access to another market, like Toyota or Honda in North America. FDI has become an important metric for both MNCs and decisionmakers seeking economic growth. For MNCs, FDI represents a way to gain access to resources, lower the cost of goods and services, and open a new market. For policymakers, FDI is a prize that will stimulate the economy and, in the process, create jobs and increase the tax base. Therefore, this investment is crucial for any country that wishes to have a high quality of life. Public policy is used to create the most favourable conditions to maintain and attract this mobile investment. Consequently, monetary and fiscal policies and the institutions responsible for them within a country are also constrained. If the policy becomes less favourable or if another locale becomes more favourable, this mobile capital may move on. This possibility has been furthered by the digital system that allows for an integration of financial markets, with the internet allowing for near-instant financial exchanges globally. The market logic seems to dictate conditions that allow for the best return on investment as compared to other countries, a competitive condition that seems to privilege low corporate taxes, fewer regulations, unrestricted labour markets, etc. However, as discussed earlier, this also comes with a possible cost to state welfare and the ability of decisionmakers to act in the best interests of their constituents.

Yet, as with commodity trading, the empirical evidence offers mixed support for the consistency of this restraint on policymaking. Although investment does seek out maximized returns, it is not nearly as mobile as this account assumes. Once money has been invested, it cannot as easily be extracted due to the cost of re-establishing capital investments, a trained workforce, and political connections. Additionally, the usual mix of neoliberal policies that supposedly are most attractive for foreign direct investment does not easily correlate with increased levels of foreign direct investment. Finally, direct foreign investment is mostly directed from and to North America, Europe, and Pacific Asia. This is less a case of globalization of capital than certain restrictions of geography and access to markets influencing decisions beyond competitive policy conditions.

Figure 7-13: Foreign direct investment. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/businessman-success-stock-exchange-2557056/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Advancements in technology also constrain policymakers, or at least serve as a mechanism through which global forces of capitalism can discipline those countries that pursue policies that do not conform to the market logic. The logic here is that financial markets are almost entirely integrated and global. If one country steps out of line, both the country’s currency and levels of foreign investment could be severely punished. But if this were the case, interest rates set by national institutions would be the same, and they are not. There continue to be differences in a variety of economic markers between countries, such as the level of domestic savings and domestic investment. The financial markets may be digital, but they very rarely exercise the option to punish policies that do not conform to what would be considered “good” economic policy, according to the market logic. As long as there is not terrible monetary inflation and budget deficits are not outrageous, financial markets do not seem to react too strongly. Rather, as suggested in our discussion of the trade-in commodities, the globalization of international finance has created both opportunities and threats for policymakers. There is variance in how decision makers respond to these opportunities and threats, which means there is the opportunity for agency and for policy ingenuity.

Let us return to the case of Danville. Think about the history of what has happened in this small town and its present situation. Local officials in Danville have developed a strategy of directing their municipally-owned utility entity to increase its share of renewable energy with solar panels. It has also used low taxes to attempt to attract business. In so doing, Danville has managed to grow its economy and reinvigorate the community. Bangalore in India has done something similar by carving out a niche in the call center industry. Each is an example of policy ingenuity and entrepreneurship and a possible case study in comparative politics. Small US municipalities may look to what worked and what didn’t in Danville and assess what applies to their city. They may ask how the process of globalization poses both threats and opportunities and, in turn, how this influences the systemic or institutional agendas, how this shapes the ideas, interests, and institutions behind policymaking, and how Danville generated a policy window to act. Further, what holds true for Danville also holds true for Bangalore or Saskatoon. Globalization is reshaping the form of the policymaking landscape. Still, it has not changed the function of policymakers – to create, implement, and evaluate policy in response to perceived opportunity and threat for the benefit of their and their constituents, interests.

If you haven’t already, read the Michael Green article (also listed in the Required Readings section of this module):

- Why we shouldn’t judge a country by its GDP,” TED.com, https://ideas.ted.com/why-we-shouldnt-judge-a-country-by-its-gdp/

Then, use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal, related to the public policy issue that you have chosen to cover in your Podcast and Policy Brief assignments:

- Why is it suggested GDP is a flawed measurement of a country’s success?

- Why is it argued the SDI is a better means?

- What does this suggest for the role of policy ingenuity and entrepreneurship?

- Is there a role for policy ingenuity in your public policy research topic?

- Are there global examples that could provide insight into policy ingenuity on your research topic?

Conclusion

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the concept of globalization to public policy analysis. It began with an investigation of the definition of globalization. It introduced the two starkly opposing positions: the hyper-globalists who argue globalization is fundamentally transformative and the skeptics who argue globalization is just an intensification of age-old processes. In an attempt to further refine the concept of globalization, we contrasted the concept with regionalization as well as considered the differing impact of globalization on developed and developing countries. In the first case, contrasting globalization with regionalization, we noted that much of what people call globalization is actually more about regional trade hubs. This would suggest that this is less of a global process and more about harmonizing policies between like-minded states. In the second case, contrasting the impact on developed and developing countries, we noted that while early opponents of economic globalization were found in the Global South, more recently opposition has been most pronounced in the labour movements of the Global North. This suggests that what many identify as the transformative impact of globalization may more likely be the global expression of class interests. From this conversation on defining globalization, we worked through the potential impact of globalization on how we do public policy analysis, from the policy cycle, through the lens of ideas/interests/institutions, to the MSA of policy analysis. We noted that globalization expands the scope of policymaking. It creates more actors and more levels of influence as well as more policy problems and potential policy solutions. From all of this, we need to consider how globalization both complicates our own comparative policy research and how it suggests more comparative examples that may allow greater policy ingenuity.

Review Questions and Answers

The strongest thesis of globalization is labelled hyper-globalization. This narrative argues we are experiencing the fundamental transformation of our global economic, political, institutional, and social structures. It is claimed we are witnessing a period of unprecedented revolution where the state is becoming anachronistic, that citizenship is less meaningful, and that the division between the foreign and the domestic has less substance. From this perspective, public policy making and public policy analysis is much more complicated. There are new actors involved, including international institutions, MNCs, and NGOs. There are new problems and new policy solutions that confront policy makers. The world is more interdependent and policymakers are more constrained in their policy choices.

The ‘globalization skeptics’ narrative argues globalization is simply an intensification of long-running global processes. They argue that the current movement of goods, money, and people around the world is no different in function than that of the ancient Chinese Silk Road – it is simply a matter of scale. If this is true, policy makers need to adjust and need ingenuity. This narrative suggests that the processes of globalization are rooted in human avarice and class politics.

Globalization can usefully be contrasted with regionalism. Hyper-globalists often use increased trade as evidence of globalization. They point to the increasingly globalized supply chains whereby goods are sourced, manufactured, and marketed in several states before being sold to the end consumer. However, increased trade between countries does not necessarily provide evidence of increased globalization per se if we are referring to trade that extends globally. Regionalism has many of the features present in definitions of globalization, such as the lowering of barriers to the movement of goods, people, ideas, and capital between countries, as well as the development of intergovernmental organizations to manage these processes. However, the critical difference is that regionalism limits these features to a particular geographical region and amongst individual member states. As a consequence, regionalism is much less transformative since the members of a region have more features in common and require less drastic steps to harmonize their economies or institutions. With regionalism, countries compete with the other more alike states, while globalization means they compete with states around the world.

Globalization has deep influence on the policy cycle generally but most specifically on the agenda setting and policy formulation stages.

For the public/systemic agenda, globalization widens the horizon of threats and opportunities that confront policymakers by creating new demands from new audiences advocating for governmental action. Globalization also broadens the institutional agenda. Decisionmakers have to be more keenly aware of threats and opportunities both at home and abroad. For example, while the federal or a provincial government may seek to support the local economy, they must factor in the decisions being made in Washington, Brussels, Beijing, and the many international organizations that impact the global economy.

In terms of policy formulation, globalization places constraints on policymakers. Policymakers need to remain competitive in a globalized world makes policymakers wary or even insecure about policies which increase the tax and/or regulatory burden on corporations, especially MNCs. If the government raises the tax and/or regulatory burden on a sector of the economy, corporations may relocate their economic activity, slow down their production, or find another cost-cutting measure such as automation. Such decisions may, in turn, increase unemployment and stress welfare provisions. As an added consequence, low levels of taxation means the very capacity to enact public policy is also constrained.

In terms of ideas, the processes of globalization influence cognitive paradigms, normative frameworks, and shifts in world culture. In terms of cognitive paradigms, policymaking is increasingly seen in a more global context, with more actors, and more opportunities and threats. This, in turn, has moved the normative framework of policymakers who have come to see the need to accommodate global capital and protect against global threats such as transnational terrorism or organized crime. Much of this has solidified in a world culture that sees an interdependent world, with goods, capital, and labour moving more globally albeit not equally nor equitably. For those policymakers who see globalization as a positive force, these ideas are used to frame the opportunities of global processes and create programmatic platforms. And, vice versa for those who see globalization as a threat.

In terms of interests, globalization has also created or at least given voice to new actors with their own interests. Most notably, the economic globalization has created MNCs that are so large and so influential they challenge the resources of many states. Another group of actors enabled by globalization are NGOs, which largely advocate for civil society on social and political issues. Finally, globalization has created a need for institutions such as the UN, WTO, the World Bank Group.

In terms of institutions, globalization has added an international layer to the policymaking context through decision making institutions, for example, the United Nations and the World Trade Organization. These institutions act as platforms through which international law, international regimes, and international norms are agreed to, are monitored, and, if possible/necessary, are enforced. Further, these formal institutions create more informal institutions that dictate expectations of behaviour.

The MSA argues that policymaking requires the convergence of the three following conditions: an identified problem, a viable solution, and the political will to implement it. Globalization, and the interdependence that comes with it, has created new problems for policy makers to address. The inclusion of new actors with new interests, also generates new policy solutions. But most importantly, it is political will that opens policy windows. This policy window appears when there is sustained attention to a problem, an identified and feasible policy response, and sufficient political will to carry it through. This is the same for domestic policymaking as it is for responding to global issues. However, globalization does complicate the process. Decisionmakers are confronted with a much broader range of policy problems, many of which might be beyond their scope to handle. They are faced with a much broader range of policy solutions as NGOs, MNCs, and IGOs all advocate for their particular interests. They are confronted with a more diverse set of demands by constituents who may perceive the processes of globalization differently from each other.

Glossary

Developed States: Refers to economically well-developed countries, usually assessed by GDP. They often have robust social welfare systems and tend towards democratic governments. The term Global North is also sometimes used in place of developed states.

Developing States: A term used in reference to less-industrialized countries but yet differentiated from least developed or under-developed states. This categorization is often based on GDP. More recently, the term Global South has been used to refer to a broader categorization of developing states.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): The act of using one's economic resources in another state for the purpose of economic activity.

Globalization: While a contested a term, most generally refers to the economic, political, and social processes which have rendered the world more interdependent and interconnected.

Globalization skeptics: Argue globalization is an intensification of long-running global processes. It argues that the current movement of goods, money, and people around the world is less a change in the function of globalization than it is of its scope.

Hyper-globalization: Posits a transformative view of current global economic, political, institutional, and social structures. It claims that we are witnessing a period of unprecedented revolution where the state is becoming anachronistic, that citizenship is less meaningful, and that the division between the foreign and the domestic has less substance.

International finance: Includes all monetary transactions that cross borders, including financial services, international investment, currency transactions, and foreign direct investment.

International governmental institutions (IGOs): Organizations created by and in the interest of states. These organizations are created to overcome issues that are beyond the capacity of any one state, often by facilitating political cooperation and functional cooperation.

Multinational corporations (MNCs): A company that is incorporated in one country but operates at least one other. However, the term is most often used in as shorthand for very large corporations that source, manufacture, and/or sell goods in globally.

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs): Civil society organizations that are perceived to be working on humanitarian issues and in opposition to the interests of MNCs and states.

Outsourcing: The practice of buying goods or services from a 3rd party vendor. In the global context, this often refers to the practice of finding the cheapest sources of inputs, parts, labour, and services internationally.

Regionalism: Represents a narrow version of the forces of globalization whereby the movement of goods, money, and people is restricted by proximity. One critical difference with globalization is that since regionalism limits these processes to a particular geographical region it is much less transformative. Regional members have more features in common and require less drastic steps to harmonize their economies or institutions. With regionalism, countries compete with the other more alike states, while globalization means they compete with states around the world.

Trade of commodities: A form of trade associated with the mobility of goods between jurisdictions.

Trade-in services: A form of trade associated with the mobility of services between jurisdictions.

Social Progress Index (SPI): A metric aimed measuring quality of life, to demonstrate that how a state responds to the opportunities and threats presented by globalized trade is, in no small degree, a function of policy entrepreneurship.

References

Lindsay, Bethany. “How B.C. Brought in Canada's 1st Carbon Tax and Avoided Economic Disaster.” CBC News. CBC/Radio Canada, April 4, 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/carbon-tax-bc-1.5083734.

Babic, Milan, Eelke Heemskerk, and Jan Fichtner. “Who Is More Powerful – States or Corporations?” The Conversation, February 18, 2020. https://theconversation.com/who-is-more-powerful-states-or-corporations-99616.

Friedman, Thomas L. The World Is Flat : A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century. Thorndike Press, 2005.

Gray, John N. False Dawn the Delusions of Global Capitalism. London: Granta Books, 1998.

Hay, C. “Globalization’s impact on states”. in Global Political Economy, ed. J. Ravenhill. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2005.

Hirst, Paul., and Graham Thompson. Globalization in Question, 2nd Edition. Cambridge: Polity Press. 1999.

Horner, Rory; Seth Schindler, Daniel Haberly, Yuko Aoyama. “Globalization, uneven development, and the North-South' big switch'.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy, and Society, Volume 11, Issue 1, March 2018, Pages 17–33

Hurrell, Andrew. “One World? Many Worlds? The Place of Regions in the Study of International Society.” International Affairs 83, no. 1 (2007): 127-46.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. Globalization and Its Discontents. New York: W.W. Norton, 2002.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. Globalization and Its Discontents Revisited: Anti-globalization in the Era of Trump. Revisited ed. 2018.

Mason Adams, Clifton Forge, Robin Bravender, Ned Oliver, Kate Masters, and Graham

Moomaw. “Solar Is Powering Part of Danville's Resurgence.” Virginia Mercury, June 13, 2019. https://www.virginiamercury.com/2019/06/10/solar-is-powering-part-of-danvilles-resurgence/.

Mosley, Layna. Global Capital and National Governments. Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics. 2003.

Rahul, Rajalakshmi, and Rajalakshmi Rahul. “Benefits of Globalisation to India.” Project Guru, November 19, 2018. https://www.projectguru.in/benefits-of-globalisation-to-india/.

Rodrik, Dani. “Why Do More Open Economies Have Bigger Governments?” Working Paper Series (National Bureau of Economic Research) No. W5537. 1996.

Plumer, Brad, and Nadja Popovich. “These Countries Have Prices on Carbon. Are They Working?” The New York Times, April 2, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/02/climate/pricing-carbon-emissions.html.

Walker, Morgan Hartley and Chris. “The Culture Shock of India's Call Centers.” Forbes Magazine, December 20, 2012. https://www.forbes.com/sites/morganhartley/2012/12/16/the-culture-shock-of-indias-call-centers/#350c54c372f5

Supplementary Resources

- Audretsch, David., Lehmann, Erik. Editor, Richardson, Aileen. Editor, Vismara, Silvio. Editor, and SpringerLink. Globalization and Public Policy : A European Perspective. 2015.

- Bhagwati, Jagdish N., In Defense of Globalization. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Ritzer, George. "Globalization and Public Policy." In The Blackwell Companion to Globalization, 429-43. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2008.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. Globalization and Its Discontents. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 2002.