Developed by:

Dr. Martin Gaal – University of Saskatchewan

Overview

In our last module, we introduced and examined the topic of immigration policy. We applied our frameworks of public policy analysis and noted that immigration policy debates are constituted by narratives of threat and of humanitarian obligation. It is a debate framed by economic and identity concerns. Moreover, policymakers are often not in control of the timing around immigration debates as they are often driven by external events and crises.

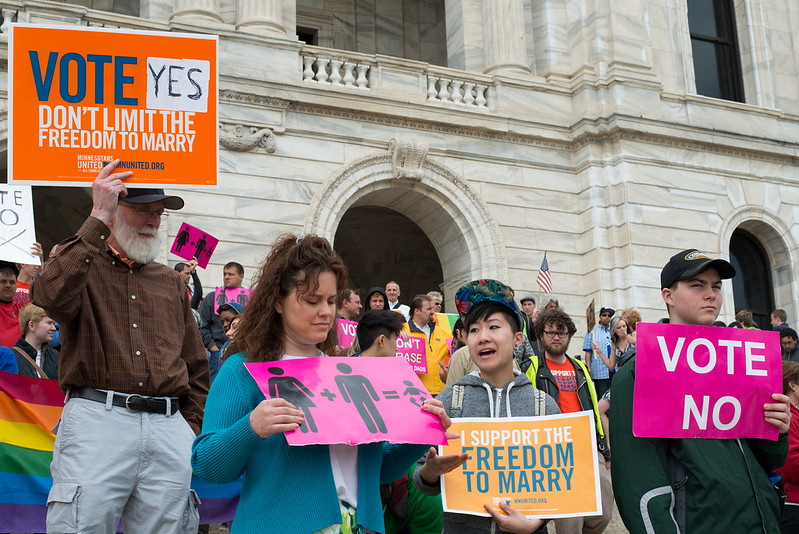

Figure 10-1: Minnesota Senate debate on same-sex marriage, 2013. Source: https://flic.kr/p/ej8eMU Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Fibonacci Blue.

In this module, we turn to another policy issue with deep divisions within society, same-sex marriage (SSM). The policy issue of same-sex marriage was, and continues to be, contentious in many places around the world. In the LGBTQ community, same-sex marriage is, for the most part, an issue of equality. The denial of marriage to same-sex couples, even when recognizing their relationship as a civil partnership, is seen by many as a form of segregation, drawing on the narrative of the civil rights movement in the US. Further, the ‘separate but equal’ status of civil partnerships lends legitimation to discrimination. In the end, recognizing that the partnership between same-sex couples is no different than any other partnership is simply an issue of fundamental human rights. For those who oppose same-sex marriage, this is an identity and cultural issue, particularly for social conservatives and fundamentalist Christians. The strongest objection to the recognition of same-sex marriage is the claim that it devalues the sanctity of the institution of marriage and threatens to destabilize the family structure. In the end, opposing same-sex marriage is about identity.

Therefore, in this module, we will start with an overview of the history of SSM, and contextualize this with examples from the US, Canada, and the Netherlands. We will then examine the policy dimensions of SSM, connecting the struggle for its legalization to the broader LGBTQ movement and to the struggle for human rights. Finally, we will examine the legalization of SSM policy through the frameworks of comparative public policy covered in this class so far: the policy cycle, the role of ideas/interests/institutions, the multiple streams approach (MSA), and critical perspectives. We will close the module with some examples of comparative public policy research on SSM.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define the policy area of same-sex marriage legalization.

- Explain the connection between same-sex marriage and the LGBTQ rights movement.

- Critically assess the role of institutions and the judiciary in legalizing same-sex marriage.

- Critically assess the role of norm diffusion in legalizing same-sex marriage.

- Same-sex marriage

- LGBTQ

- Civil partnership

- Legalization

- Human rights

- ‘Gay Liberation’ movement

- Defense of Marriage Act

- ‘Gay conversion’ therapy

- Canadian Human Rights Act

- Common-law relationships

- Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- ‘The Civil Marriage Act’

- Norm diffusion theory

- Stonewall Riot

- Queerlaw

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

Smith, M. (2005). The politics of same-sex marriage in Canada and the United States. PS: Political Science and Politics. 38(2): 225-229. [See file in Canvas]

Learning Material

Introduction

The struggle for the legalization of same-sex marriage is a global struggle but is often rooted in very particular debates. It is a global struggle because every country includes LGBTQ communities, and this lends a universality to the debate. Making the debate even more universal is the link between SSM and the fight for equality and basic human rights. However, there is great diversity in the ways that particular countries interact with LGBTQ communities. Many states, like Canada and Western European states, have strong majorities in favour of LGBTQ rights and SSM – however, it should be noted this doesn’t mean discrimination or persecution does not exist. In other states, like Russia or Nigeria, there is very low acceptance of LGBTQ rights and even state-sponsored aggression against LGBTQ communities. This creates a duality in the public policies on legalizing SSM – it is both universal and particular.

In terms of public policy, this duality raises interesting questions. How have particular countries responded to demands for LGBTQ rights more generally and for the legalization of SSM more particularly? Why have some states been more willing or able to legalize SSM while other similar countries have struggled to do so? In other words, how do the universality of human rights and the particularities of individual countries influence debate(s) on the legalization of SSM?

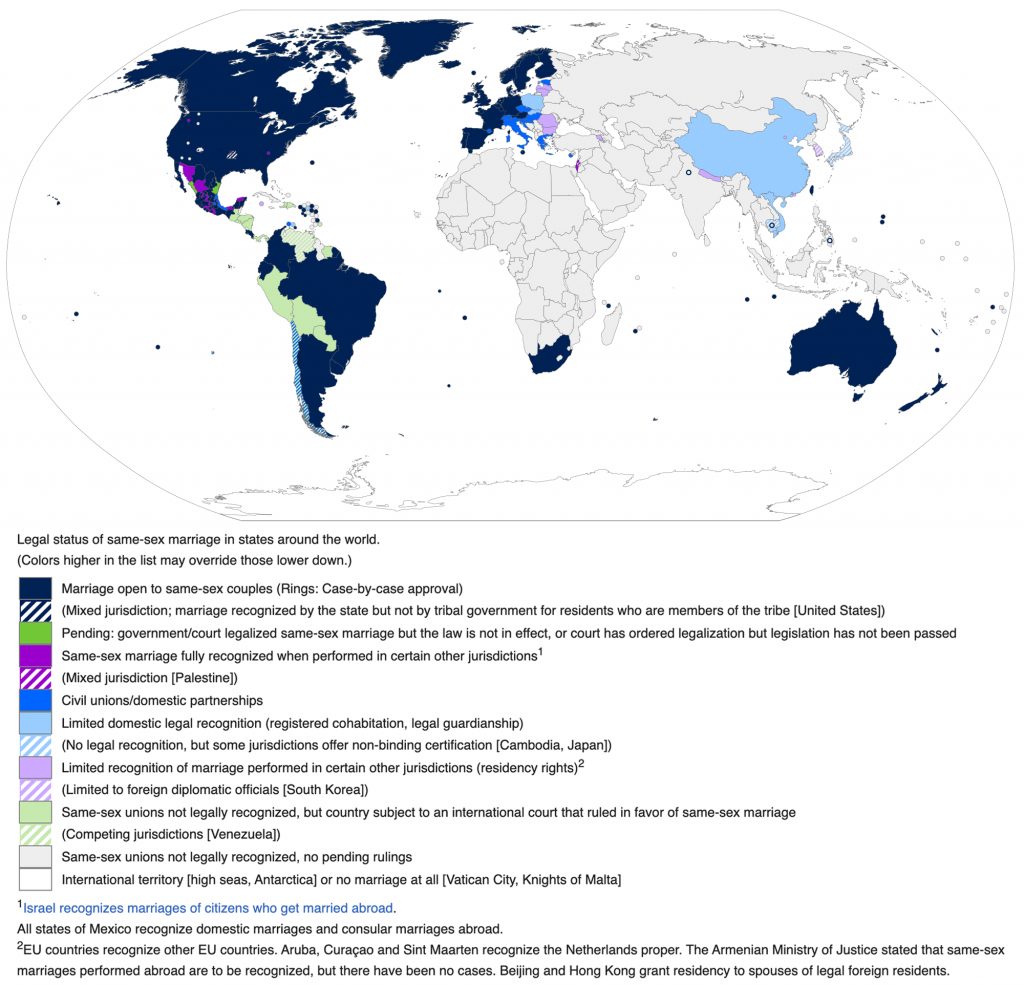

Figure 10-2: Countries and territories where same-sex marriage and similar legislation has been enacted. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_marriage-equality_laws_(up_to_date).svg#/media/File:World_marriage-equality_laws_(up_to_date).svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Kwamikagami.

Before moving on, let us assess your knowledge on the status of same-sex marriage around the world.

Take the following quiz: https://www.jetpunk.com/user-quizzes/26185/gay-marriage-countries

*Note: the list of countries in the quiz includes 27 countries but excludes Costa Rica which legalized SSM in 2020, and Mexico which has legalized SSM in some states but not nationally.

On the following Padlet board, add a post with the following:

- Your score out of 27.

- One country that surprised you – were you surprised to find it on the list, or not to find it on the list?

- One country that surprised you due to its chronological placement – was it a very early adopter, or late adopter, compared to other nations that you might consider to have similar values?

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include your Padlet contribution.

Historical Context for Same-Sex Marriage

Contemporary advocacy for the recognition of same-sex marriage is an ongoing global struggle in the LGBTQ community. It is a policy area that is highly divided globally, with the discourse ranging from celebration to criminalization and implicit, if not explicit, approval of persecution. That being said, it is also important to step back and recognize that the official recognition of same-sex partnerships is not in any way new. As Eskridge (1996) notes, there are references to the formal recognition of same-sex partnerships in Ancient Egypt, Canaan, Mesopotamia, Greece, and Rome and Celtic society and Indigenous groups in North and South America name a few. However, the contemporary struggle for official recognition of same-sex marriage emerged from the LGBTQ movement, starting in the 1970s but taking more prominence in the 1990s.

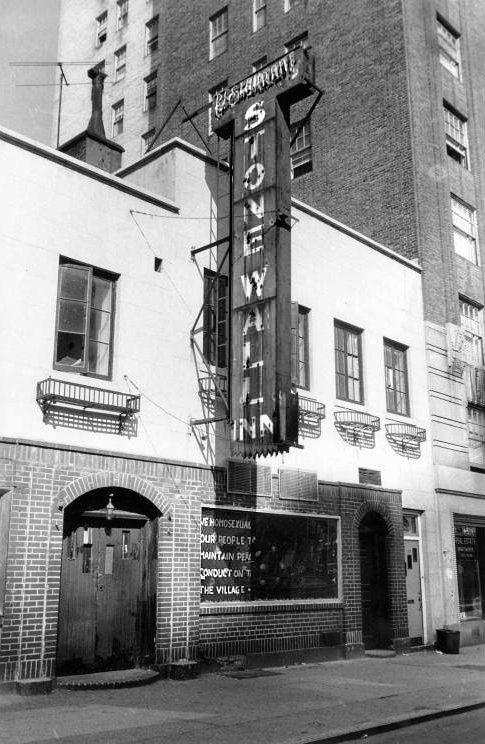

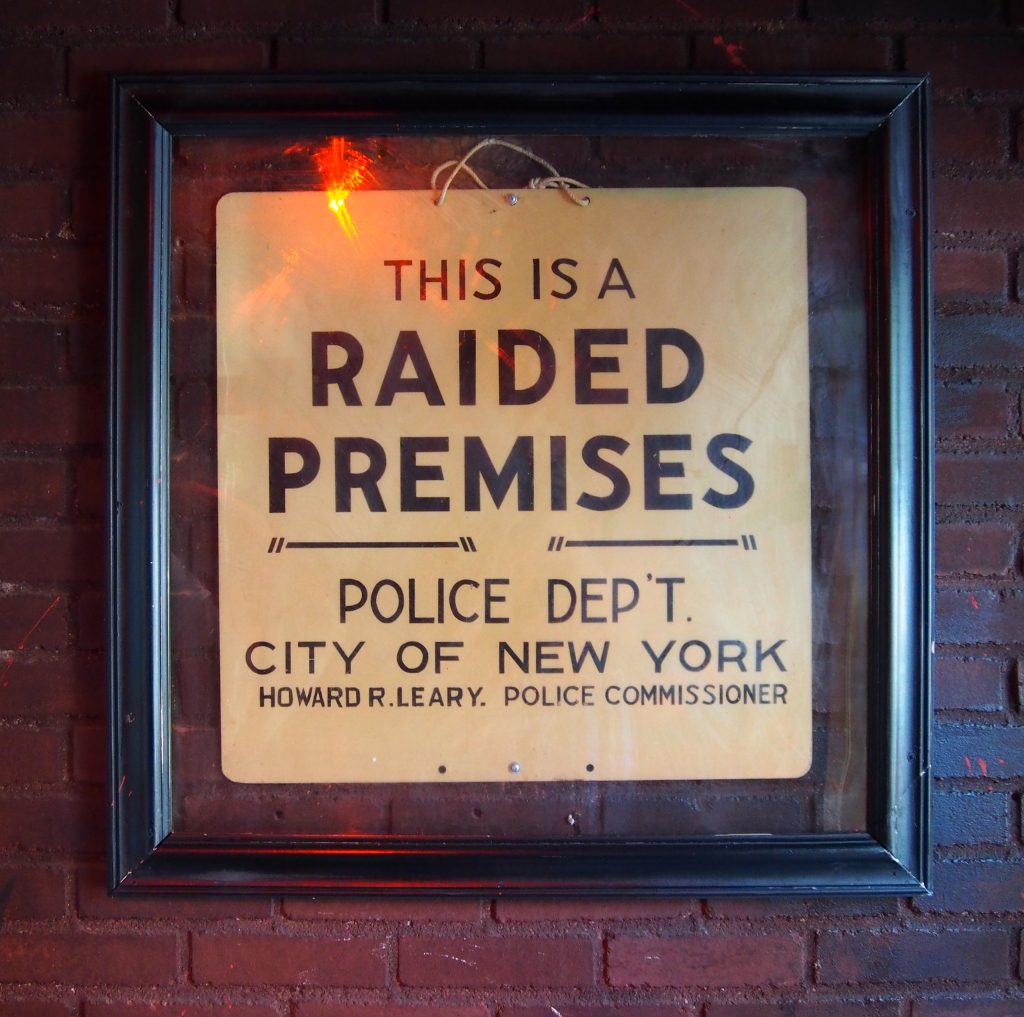

If we want to understand the debates over same-sex marriage, it is important to contextualize it in the LGBTQ rights movement. Many scholars trace the beginning of the modern LGBTQ rights movement to the mid-1960s. One particularly critical moment was the famous riot at the Stonewall Inn in New York City in 1969. After a police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in Greenwich Village, frustrated patrons took to the streets outside the bar to protest the repeated targeting of the bar and its patrons in police raids. Although rights demonstrations had been occurring for some years previously, such as the first US gay-rights demonstrations in 1965 in Philadelphia and New York, the Stonewall Riot sparked an increased level of activism. What had been long-simmering frustrations over discrimination and over-policing finally came to the forefront. The ‘Gay Liberation’ movement, as it was then known, was a collection of a variety of different activist organizations committed to advocating for the rights of queer people.

Figure 10-3: A photograph of the Stonewall Inn, famed and widely recognized after the events of June 28, 1969, which would change the public conception of LGBT peoples in the United States. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stonewall_Inn_1969.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of New York Public Library. |

Figure 10-4: The “raided premises” sign just inside the door at the Stonewall Inn. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stonewall_Inn_raid_sign_pride_weekend_2016.jpg#/media/File:Stonewall_Inn_raid_sign_pride_weekend_2016.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Rhododendrites. |

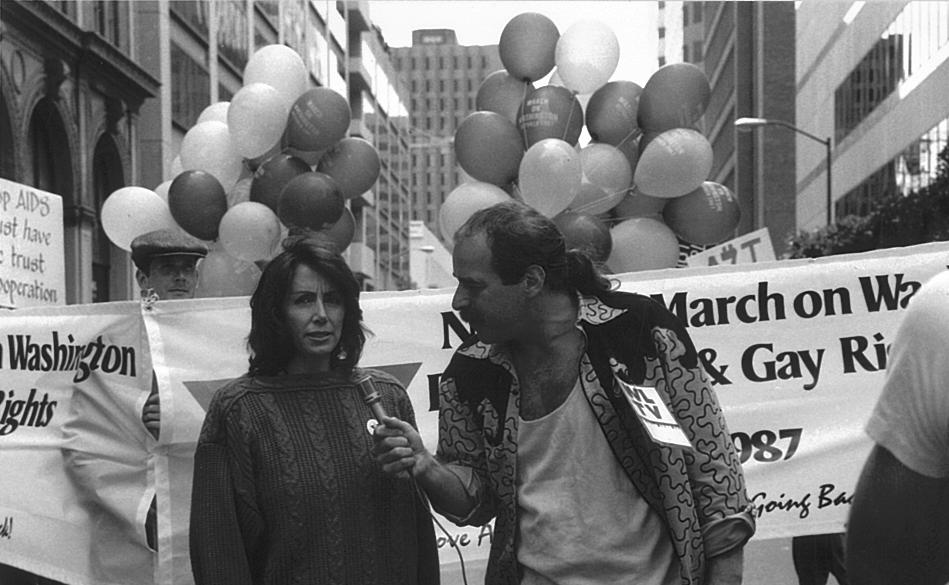

Similar movements were also occurring during the same period in other countries, including Canada. During the 1960s, the high-profile case of Everett George Klippert, a gay man jailed and declared a dangerous offender because he was gay, sparked a nationwide debate over the morality of criminalizing homosexuality. The federal government responded by decriminalizing same-sex relations in 1969. In 1971, the government released Klippert from prison the same year as the first gay rights march in Ottawa. In both the United States and Canada, gay rights activists would advocate for an end to discrimination based on sexual orientation or identity and protest police violence directed at the gay community, such as the raid on the Stonewall Inn. Police raids on bathhouses, bars, clubs, or other establishments frequented by gay people, would be a significant issue that activists sought to end. During the 1980s, the AIDS crisis presented a significant challenge to gay activists. Responding to a lack of funding for medical research or compassion for those affected by the epidemic, activists pressed for the government to react appropriately to the crisis. Large-scale protests occurred, such as in 1987, where approximately a million protesters marched on Washington.

Figure 10-5: Congresswomen Nancy Pelosi at the 2nd National March on Washington in 1987. Source: https://flic.kr/p/cGsHxs Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Nancy Pelosi.

During this same period, the social conservatives and fundamental religious groups began to organize opposition to the gay rights movements, pushing for religious exemptions to the anti-discrimination policies that were starting to emerge. These groups would form much of the organization opposing efforts to end discrimination against minority sexual orientations and identities. They typically argued such policies violated the individual religious rights of those intolerant of people with different sexual orientations or identities. In the 1990s, same-sex marriage policy emerged as a focal point for LGBTQ activists. They argued that this is an issue of equality and human rights. On the other side, socially conservative and fundamental religious groups organized to oppose the recognition of same-sex marriage. They argued that while civil unions were acceptable for same-sex couples, marriage was an institution that was already under threat and required protection. As we will see, how successful these interest groups were in pursuing their policy goals in the United States and Canada differed greatly.

Figure 10-6: Arguments at the United States Supreme Court for Same-Sex Marriage on April 28, 2015. Source: https://flic.kr/p/s5hPpK Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Ted Eytan.

In the following decades, LGBTQ rights activists have been successful in changing public opinion. In both Canada and the United States, opinion polling shows a dramatic shift from a majority of respondents viewing same-sex relationships as immoral to a majority of respondents now viewing same-sex relationships as no different than other-sex relationships. As noted earlier, a flagship policy goal that developed during this period for the gay rights movements was legalizing same-sex marriage (SSM). Although LGBTQ rights activists seek various policy goals, such as anti-discrimination legislation and opposing police violence, SSM emerged during the 1990s and continues to be a major policy objective. Since the 2000s, this policy objective has become a significant priority for activists and governments worldwide. There are currently 29 countries where SSM is legal.

Watch the TED Talk “A Queer Vision of Love and Marriage” by Tiq Milan and Katrin Milan https://www.ted.com/talks/tiq_milan_and_kim_katrin_milan_a_queer_vision_of_love_and_marriage?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How do Tiq and Katrin introduce themselves and their relationship?

- Tiq and Katrin argue, ‘we constantly experience this retelling of history where we are conspicuously left out.’ What do you think they mean?

- How do the experiences that Tiq and Katrin share make sense of LGBTQ advocacy? How does this relate to the policy area of same-sex marriage?

Same-Sex Marriage as a Comparative Public Policy Issue

Same-sex marriage has become a policy issue in an increasing number of countries. In terms of timelines, some of the earliest advocacy for recognition of marriage equality started in the United States. However, as noted above, some of the most organized and vociferous opposition to same-sex marriage is also rooted in the US. James McConnell and Richard Baker applied for a marriage license in Minneapolis in 1970 and sued the District Clerk for refusing their request. The Supreme Court of Minnesota upheld the denial of the marriage certificate as lawful. The US Supreme Court dismissed the case of Obergefell vs Hodges’ for want of a substantial federal question.’ Obergefell vs Hodges would obstruct any legal movement on the legalization of SSM in the United States until overturned in 2015 when the Supreme Court argued that the constitution grants same-sex couples the right to marry. Through the 1970s, advocacy for SSM was met with increasing pushback from opposition groups, making it a political issue. In 1973, Maryland was the first US state to ban same-sex marriage, and at the peak in 2010, 41 states had bans in place. The most important legal tool to oppose SSM was the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) signed grudgingly into law in 1996 by President Bill Clinton under pressure by social conservative groups. DOMA defined marriage as a union between one man and one woman, and in section two allowed states not to recognize SSMs legally consecrated in other jurisdictions. Since the 2015 Supreme Court ruling, SSM is a fundamental right recognized by law in all 50 states. However, the exercise of that equality is still very much theoretical with numerous practical obstacles. For example, in 29 US states, LGBTQ folk can be fired from their jobs and denied housing based on their sexual orientation or gender identity, and there is no federal law protecting them. They face a higher incidence of violence with fewer resources devoted to protection and resolution. Only eight states have banned the harmful practice of ‘gay conversion’ therapy, often forced on children by their parents. In 2018, the US Supreme Court ruled that a baker was entitled to refuse to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple based on religious beliefs. Even bathrooms have become a battleground, with social conservative groups ramping up opposition to people using the facilities not designated for their gender at birth – as Gordon (2016) argues, this doesn’t seem to be about what people do. Rather it seems to be an objection ‘to what people are.’ Closer to the policy of SSM, while the courts have said same-sex couples can marry and can technically adopt children, LGBTQ couples do face legal and other restrictions to adoption. Some states allow adoption agencies to discriminate based on sexual orientation, most often citing the protection of religious beliefs. Same-sex couples also face significant obstacles to ‘second-parent adoption,’ which allows a parent to adopt their partner’s biological or adopted children. All of this suggests that the policy of SSM in the US is highly contentious and politically loaded.

Figure 10-7: Marriage Equality Rally in front of the US Supreme Court, Washington DC, 2015. Source: https://flic.kr/p/snHCJR Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Elvert Barnes.

Historically, Europe has had a mixed policy response to LGBTQ folk and, more recently, towards the legalization of SSM. There are a few examples of relatively more equality, such as expanding the decriminalization of same-sex couples during the French Revolution. There are also many examples of extreme discrimination against LGBTQ folk, such as 17th century Prussia which punished sodomy with death and Nazi Germany, which forced ‘homosexuals’ into concentration camps. However, in contemporary debates, Europe has become a much more progressive force for equality. Pew Center Research in 2017 demonstrated overwhelming support for LGBTQ rights more generally and, in particular, the legalization of SSM in Western Europe. In Italy, a country with strong Catholic traditions, nearly 60% of the people approve of legalizing SSM, and in Sweden, that number climbs to 88%. The Netherlands was the first state to legalize SSM in 2001, and as of 2019, eighteen countries have done so, with Northern Ireland being the latest in 2020. The other Western European states have recognized same-sex unions or civil partnerships, but not marriage, including large countries such as Italy, Hungary, and Greece. Surprisingly, the European Union does not require its members to legalize SSM. Still, it requires Member States to uphold same-sex couples’ freedom of movement and residence within the EU. While far short of what SSM advocates would like, the influence of the EU can partly explain shifts in members like Croatia, which constitutionally banned SSM in 2013, but then recognized civil partnerships in 2014. In Eastern Europe, support is much lower. According to a 2017 Pew Research Center poll, large and regionally significant countries have very low support for SSM, including Poland at 32%, Hungary at 27%, Ukraine at 9%, and Russia at 5%. Russia has been increasingly harsh in persecuting same-sex couples. In 2013, the Russian government criminalized the distribution of ‘propaganda of non-traditional sexual relationships to minors.’ The intent behind the law is generally understood as institutionalizing LGBTQ discrimination and persecution as well as legitimating and condoning hate crimes. In 2020, Putin proposed a constitutional change that would ban SSM.

Figure 10-8: Berlin demonstration against homophobia in Russia, 2013. Source: https://flic.kr/p/fFN9Q3 Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Marco Fieber.

In Oceania and East Asia, only New Zealand, Australia, and Taiwan recognize and perform SSM. Support is much lower elsewhere. There are low approval ratings for SSM in China at 31%. There is a ban on male same-sex couples in Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Singapore. In Brunei, same-sex relations are punishable by death or whipping for men and caning or imprisonment for women. In South and Central Asia, same-sex relations are broadly illegal, except for India and, to a lesser degree Nepal. In the Middle East and North Africa, LGBTQ relationships are mostly illegal, and in Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, they are punishable by death. There are a few exceptions in the Middle East. In Jordan, LGBTQ relationships are not illegal, but public displays of affection between LGBTQ folk are punishable. One exception is Israel, which recognizes SSM and adoption rights for same-sex couples. In Africa, more broadly, only South Africa has legalized SSM, and Cape Verde has put broader protection in place for LGBTQ folk. However, in all 53 African states, other than South Africa and including Cape Verde, LGBTQ relationships are not recognized. In 34 African countries, LGBTQ relationships are illegal. In 8 of those countries, it can result in life in imprisonment or the death penalty. On a more positive note, there has been increasing public support for LGBTQ rights in South Africa, Cape Verde, Mozambique, and Namibia. On the institutional side, it has been noted that the courts in Botswana, Kenya, Uganda, and Zambia have supported LGBTQ advocacy groups.

Figure 10-9: Protestors in London marching in solidarity with Uganda’s LGBTI community, 2018. Source: https://flic.kr/p/26hoihy Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Alisdare Hickson.

In the Americas, LGBTQ rights are more complex. SSM is legal in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and the United States. In Mexico, SSM is recognized in the capital and many states but not nationally. In a 2018 judgement, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights recognized SSM as a human right, leading to Costa Rica’s shift in policy. This ruling also means by extension that Barbados, Bolivia, Chile, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Suriname are obligated, but as of yet have not recognized, SSM as a human right. However, support for SSM varies widely. At the top, 64% of Canadians approve of SSM according to a 2019 Research Co. Poll, and at the bottom is Jamaica at 16%, according to an International LGBTI Association poll. It is also important to note that Jamaica still has not repealed laws against sodomy. In general, support for SSM is lowest in the Caribbean and Central American states. On a less positive note, the election of the right-wing populist in Brazil, Bolsonaro, has prompted advocacy for a constitutional shift against LGBTQ rights.

Figure 10-10: “Women United Against Bolsonaro” march, Westminster, 2018. Source: https://flic.kr/p/2btYhgb Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Esdras Beleza.

This section of the module will close with a look at the history of SSM in Canada. The first step towards legalizing SSM in Canada began with the Haig and Birch v. Canada (1992) decision at the Ontario Court of Appeal. The court ruled that failing to include sexual orientation in the Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA) was discriminatory. In the Mossop Case (1993), the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that denying bereavement leave for same-sex couples is not discriminatory because of the definition of family status in the CHRA. However, the court also noted the outcome might have been different had section 15 of the CHRA been argued, as it states:

In 1995, Egan and Nesbitt sued Ottawa for the right to claim a spousal pension for same-sex couples. In the same year, an Ontario Court rules that denying same-sex couples the right to adopt violates Section 15 of the CHRA. In 1996, the government amended the CHRA to include sexual orientation. In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled denying same-sex couples equal benefits and obligations was discriminatory. In 2000, the government amended legislation to give equal treatment to same-sex couples regarding social and tax benefits by including same-sex couples in the definition of common-law relationships. In the same year, BC and the City of Toronto asked the courts whether SSM is constitutional. The first Canadian SSM ceremony was held in Ontario in 2001, but the province does not legally recognize them. In 2002, the Ontario Supreme Court argued prohibiting SSM violated the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In response, Alberta passed legislation banning SSM. In 2003, several things happened to push forward on the policy of SSM. First, MP Svend Robinson introduced a private member bill to legally recognize SSM. The Ontario Court of Appeal upholds a lower court decision to allow SSM. Soon after the decision, Michael Leshner and Michael Stark were the first same-sex couple to marry in Canada legally. In 2003, the BC government legalized SSM, the Federal Government announced its intentions to pass legislation to make SSM legal, and the courts made benefits for same-sex couples retroactive. In 2004, Quebec, Manitoba, and New Newfoundland and Labrador joined Ontario and BC in recognizing SSM.

In 2005, Bill C-38, a.k.a. ‘The Civil Marriage Act’ provided same-sex couples with the right to marry, making Canada the fourth country in the world to legalize SSM after the Netherlands (2001), Belgium (2003), and Spain (2005). In the end, the SSM legislation was politically costly for both parties and remains politically contentious. In response to the introduction of Bill C-38, Paul Martin’s minority government lost a cabinet minister, Joe Comuzzi, who resigned so that he could vote against SSM. SSM has proven contentious for the Conservatives as well. In 2006, the Government of Stephen Harper introduced a motion to open a debate on SSM. It was defeated by a vote of 175 to 123, with twelve conservative MPs and five cabinet members breaking ranks with the government. SSM is still politically sensitive today, with roughly 25% of Canadians opposing it. This sizeable, but minority position, has proven problematic for the Conservatives and, to a lesser degree, the Liberals. In the 2019 election, the Conservatives under Andrew Scheer had to deal with past statements opposing SSM. This forced the Conservatives to consider potentially alienating their socially conservative base or the majority opinion of Canadians. For the Liberals, supporting SSM is used as another wedge issue in the West, primarily Alberta and Saskatchewan – opponents argue that the Liberals are hiding behind socially progressive outrage to cover up a weakness in policy or their record.

Figure 10-11: Michael Hendricks and René Leboeuf, the first same-sex couple to legally marry in Quebec. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hendricks-leboeuf2.jpg#/media/File:Hendricks-leboeuf2.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Montrealais.

Watch the CPAC video “Pillars of Democracy: legally married” https://youtu.be/6xQS2QYyXxE

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How is advocacy for SSM in Canada rooted in the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms?

- a. Why/how is the story of SSM in Canada rooted in the courts?

b. How does this force the provincial and federal governments to confront SSM? - a. How did the governments respond?

b. Why is a constitutional review important and essentially political? - In the video, ‘the Michaels’ argue that marriage is a primal issue, that everyone understands marriage, that this made their wedding a world story. What is the significance of this statement?

- How does SSM create a policy nexus of social, political, and legal debate?

Applying the Frameworks of Comparative Public Policy Analysis

Much like we did in the previous module, we will now turn back to comparative public policy analysis frameworks to make sense of SSM. Recall the following frameworks from earlier modules:

- The Policy Cycle

- The roles of Ideas, Interest, and Institutions

- The Multiple Stream Approach (MSA)

- Critical Perspectives

- Comparative Public Policy

Let’s look at each of these more closely.

1. The Policy Cycle

For most places in the world, 164 countries to be exact, SSM is still not legal and therefore is very much still limited to the systemic agenda. In a few states, there is even advocacy to ban SSM, such as Russia. In Bermuda, a British Overseas Territory, SSM was legalized in 2017 but then banned in 2018 and reduced to domestic partnership. However, those SSMs in Bermuda between the 2017 decision and the 2018 ban remain valid and recognized. As a whole, we see the policy of SSM very much in the agenda-setting and the evaluation stage of the policy cycle.

The Agenda-setting Stage

In the policy issue of SSM, advocacy on the systemic agenda has been pivotal. But this advocacy, although crucial, is a bit different than found in other policies. It is useful to review the difference between the systemic or public agenda and the institutional agenda to understand how the policy issue of SSM is different. The public or systemic agenda refers to all those issues that are being debated in the body politic. The institutional agenda refers to a much narrower set of issues the decisionmakers decide to debate and choose whether to act on or not. Many of the issues on the institutional agenda are put there through determined advocacy on the systemic agenda. However, it is important to remember that many issues on the systemic agenda never make it to the institutional agenda. Those that do often follow a similar pattern. Advocacy groups build support in the community. They work with epistemic communities to derive and frame policy options. They lobby government departments, bureaucrats, stakeholders, and decisionmakers to get their policy on the institutional agenda and for their preferred policy preferences if successful. They look for influential champions to promote their cause. For example, Canada’s public health care system was undoubtedly on the systemic agenda, but Saskatchewan Premier Tommy Douglas also championed it. It was Tommy Douglas that provided the impetus to open a policy window on public health care. Although SSM also has its advocacy groups, epistemic community, and champions, it has also deviated from this path in significant ways. For example, as mentioned earlier, SSM has been a central policy objective for the LGBTQ advocacy groups in Canada. They also did have some important supporters, such as PM Paul Martin and MP Sven Robinson. Still, Martin and Robinson did not open a policy window in the same way that Tommy Douglas had for public health care. It would have been difficult for them to do so because the public support was not strongly in favour of legalizing SSM, and the opposition was deeply motivated. In 1997, only 41% of Canadians supported SSM. Rather, the policy window for SSM was opened by advocacy through the courts, which we will discuss in the next paragraph on the evaluation stage. However, this does not mean advocacy was unimportant – LGBTQ advocacy has advanced many rights, and SSM would arguably not have been achievable without such advocacy. While only 41% of Canadians supported SSM in 1997, that support increased to 74%, and societal norms and attitudes influence the courts. Today, support for the LGBTQ more generally can be seen in the degree to which symbols like the Pride Parades have become mainstream.

Figure 10-12: PM Trudeau at the 2015 Pride Toronto Parade. Source: https://flic.kr/p/vBcWFe Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Alex Guibord.

The Policy Evaluation Stage

While the agenda-setting stage is significant in understanding the recognition and legalization of SSM, the role of policy evaluation was pivotal, most particularly judicial evaluation. Judicial evaluations assess the legal authority of a policy. It asks whether agents have acted appropriately in terms of authority, jurisdiction, and in accordance with the Constitution. SSM has been deeply influenced by judicial evaluation, albeit indirectly. Since SSM is a new policy, it was not under review in the traditional sense. However, those who were advocating for SSM sought a judicial review of human rights legislation and the constitutionality of denying marriage equality between same-sex couples and other-sex couples. For example, in the Netherlands, the legalization of SSM was largely a result of Dutch LGBTQ advocacy on SSM built on a 1983 change to the Constitution and a 1990 court decision. In 1983, the Netherlands rewrote the Constitution and enshrined protection from discrimination, albeit not explicitly sexual orientation. In the 1980s, LGBTQ advocacy groups challenged the legal privileges of marriage: adoption, partner immigration, pensions, and tax benefits. In 1990, a same-sex couple lost their case to have their marriage recognized at the Supreme Court. However, the court also noted lawmakers could legislate a solution to the issue of SSM. The combination of LGBTQ advocacy and the clear indication by the court that the existing policy was discriminatory put pressure on the government to legislate an SSM policy. The role of judicial review is even more central in the case of legalizing SSM in Canada.

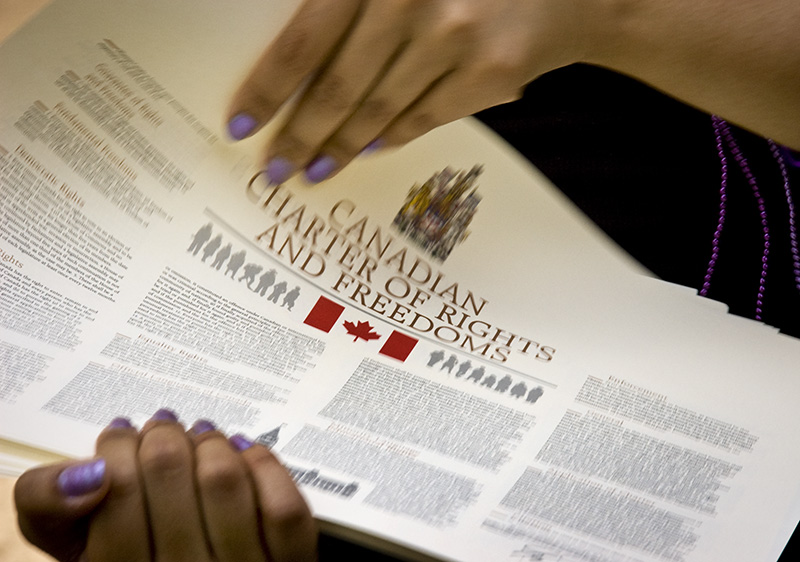

For Canada, the legalization of SSM is rooted in judicial evaluations of two foundational documents, the Canadian Human Rights Act (1977) and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982). Between the decriminalization of same-sex relations in 1969 and the passing of the ‘Civil Marriage Act’ in 2005, provincial and federal court rulings in a series of cases pushed for greater equality for same-sex couples. (see the last section for a list of specific cases) These court cases moved Canada closer to recognizing SSM to comply with the sexual orientation provisions of the Canadian Human Rights Act and Section 15 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Yet despite this trajectory, significant portions of Canadian society were still resistant to the idea of SSM, and the Federal Government was reluctant to act. For example, despite the 1999 Supreme Court Decision that ruled discrimination against same-sex couples regarding benefits violated the Charter of Rights of Freedoms, the Federal Justice Minister Anne McLellan stated the government had ‘no intention of changing the definition of marriage or legislating same-sex marriage.’ In 2000, the Federal Government introduced Bill C-23, the ‘Modernization of Benefits and Obligations Act,’ that gave same-sex couples the benefits and obligations as common-law couples. While this brought the government in line with the 1999 Supreme Court decision, the government still defined marriage as being between one man and one woman. The provinces were struggling with the 1999 decision as well. In 2000, Alberta passed Bill 202, which stated they would use the notwithstanding clause of the Constitution if the courts included same-sex couples in the definition of marriage. In the same year, the BC government asked the courts whether SSM is constitutional, and Ontario refused to register the two SSM ceremonies performed by Rev. Brent Hawks of the Metropolitan Community Church. Finally, in 2002, the Ontario Superior Court ruled that prohibiting SSMs violates the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Again, Alberta threatened to use the notwithstanding clause if Ottawa followed Ontario’s lead in recognizing SSM. In 2003, the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld a decision allowing SSM and hours later, ‘the Michaels’ are married. In the same year, BC followed Ontario’s lead and legalized SSM and the federal government of Jean Chretien announced the intention to legalize SSM with The Act Respecting Certain Aspects of Legal Capacity for Marriage. In 2004, Quebec, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador joined Ontario and BC in legalizing SSM, most under pressure from court decisions. In 2005, Bill C-38 was passed in the House of Commons by the Liberal Government, albeit at a price – several Liberal MPs voted against the bill, including the Minister for Northern Ontario who resigned from cabinet to do so. But SSM was now legal throughout Canada. The takeaway from this section is that the courts and judicial evaluations of legislation and the Constitution.

Figure 10-13: Supreme Court of Canada. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Nine.jpg#/media/File:The_Nine.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Jamie McCaffrey.

2. The Roles of Ideas, Interests, and Institutions

Ideas

Ideational factors have played an important role in the legalization of SSM both in Canada and around the globe. More specifically, we can see the role of changing normative frameworks and changing world culture. Normative frameworks are societal constructs that are defined by values, identities, and role expectations. They shape expectations of what should be. Policymakers are both consciously and subconsciously aware of the prevailing normative frameworks. Subconsciously, normative frameworks deeply influence everyone. We are, in many ways, a product of our societal values, identities, and role expectations. And policymakers are no different. They are a product of their societies. However, unlike the average member of society, they are also keenly aware of role expectations as decisionmakers. They seek out the pulse of society since public opinion is integral to their role. The normative framework around LGBTQ communities and SSM has shifted dramatically in recent history. In Canada, it wasn’t so long ago that the LGBTQ communities were openly persecuted. In the 1960s, the RCMP monitored LGBTQ folk and had a unit in the Directorate of Security and Intelligence dedicated to removing LGBTQ people from government and law enforcement. The rationale for doing so was a fear that being LGBTQ was enough to make people vulnerable to blackmail, which made them a security risk. Earlier in the module, we mentioned the injustice of George Klippert’s indefinite detention for ‘gross indecency’ and being labelled a ‘dangerous offender.’ In 1969, there was a shift in the normative framework when PM Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal Government decriminalized same-sex relations. Trudeau famously stated that ‘the state has no place in the bedrooms of the nation.’ This decision was a turning point in LGBTQ rights in Canada and represented a shift in the normative framework. But it did not change the normative framework. Nor did it represent a new normative framework. Instead, it represents the work of LGBTQ advocacy in changing the values and identities in Canada. And it represents a shift from societal discrimination towards societal acceptance. Importantly for SSM, changing normative frameworks, and especially the degree to which they subconsciously shape the opinion of decisionmakers and judges, set the stage for the series of political and legal decisions that led to the legalization of SSM in 2005.

An interesting aspect of SSM as a public policy issue is the seeming disconnect between public opinion and policy outcomes. It is more common for public opinion to lead the way on policy change, but in the case of SSM, it seems to be driven by a judicial evaluation of pre-existing human rights policies. In this sense, LGBTQ rights, and by extension SSM, are tied to a broader discourse in world culture on human rights. This discourse argues that all humans are born with intrinsic rights, as specified in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Denying women, or minorities, or political dissenters, equal treatment violates their human rights. This is very much the argument made by LGBTQ advocacy groups to the public, the government, and the courts: denying SSM violated Canadian human rights obligations as specified in the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Figure 10-14: The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Every_Canadian_Needs_A_Copy.jpg#/media/File:Every_Canadian_Needs_A_Copy.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Marc Lostracci.

One argument that makes sense of this is process is norm diffusion theory. Norms are social expectations and informal rules that regulate societal values and prescribe behaviour. Norm diffusion theory suggests that these societal values and the associated behaviour can spread both domestically and internationally as well as between issue areas. Kollman (2007) argues the acceptance and development of norms around human rights include LGBTQ rights. In turn, the acceptance and development of LGBTQ rights create a basis for, and the expectation of, legalizing SSM. We can see this in Canada, where advocates used the courts to define and expand on LGBTQ rights more generally and on SSM more specifically. However, we can also use norm diffusion theory to explain the diffusion of same-sex marriage debates throughout western democracies. In essence, an international norm influencing states to offer same-sex couples some sort of legal recognition developed, and it is the influence of this norm that led to the uptake of SSM policy in these different countries. Norm diffusion theory can also explain the uptake of SSM beyond western democracies. For instance, Ayoub (2015) used norm diffusion theory and the role played by the development of transnational networks of activists to explain the development of LGBT rights in central and eastern European states. Similar to the analysis by Kollman, Ayoub found that steadily developing international norms to recognize same-sex relationships and the influence of international activist networks were potentially more important than domestic factors when explaining the uptake of SSM outside of Western European Democracies and former European colonies like Canada.

Figure 10-15: Protests in Washington, DC, January 21, 2017, one day after Donald Trump was sworn in. Source: https://flic.kr/p/RiGs1z Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Lindsey Jene Scalera.

Interests

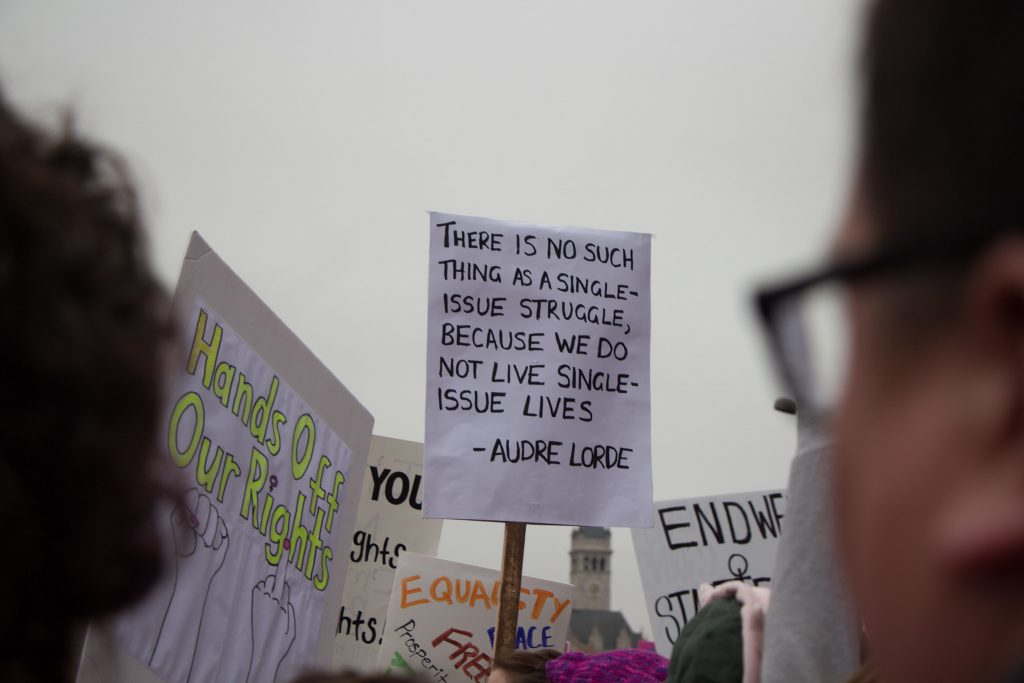

In many ways, LGBTQ advocacy is a model of identity politics. While forms of LGBTQ communities have existed in every documented culture, there has been a pervasive and institutionalized system of persecution and discrimination in place for hundreds of years. Contemporary examples of such discrimination and persecution can range from the lack of protection against discrimination in housing or jobs in some US states to the outright hostility and violence found in Russia today. While there have been significant legal and legislative achievements in Canada, there are still ample examples of hate crimes directed against the LGBTQ communities. There is still evidence of prejudice in policing. There is still censorship of LGBTQ books and media. And while there is a plan to introduce legislation to ban ‘Conversion Therapy’, as of May 2020, it is still legal. In order to push back against such persecution and discrimination, LGBTQ advocacy groups have been organizing since the late 19th century. This advocacy has worked in tandem with other social movements, like the civil rights movement and women’s rights movements. It has acted locally, nationally, and transnationally. As noted earlier, the LGBTQ rights movement became more mainstream following the Stonewall Riot in 1969. The yearly Pride Parades held around the world have been held to commemorate the Stonewell Riot. Since then, LGBTQ advocates have decriminalized same-sex relations and removed discriminatory policies around employment, housing, and benefits. They sought to allow LGBTQ folk to serve in the military. They seek to push back against the stigma of AIDS. They seek to identify and address hate crimes and unequal treatment by the police and the courts. Finally, SSM has been pursued both as a human right and as a symbol of equality. Over this time, popular culture has mirrored the developments of LGBTQ advocacy. More and more movie stars, athletes, and influencers have ‘come out’ as LGBTQ. However, the LGBTQ movement has also been fractured and divided. The leadership of the early LGBTQ advocacy in the 1970s was predominantly white and male. In response, lesbians influenced by feminist organizers formed their own movement. And both groups have at times failed to recognize the intersectionality of being LGBTQ and a person of colour. These tensions still exist within the larger LGBTQ movement. It is entirely possible to be gay and racist or transphobic or sexist, for example.

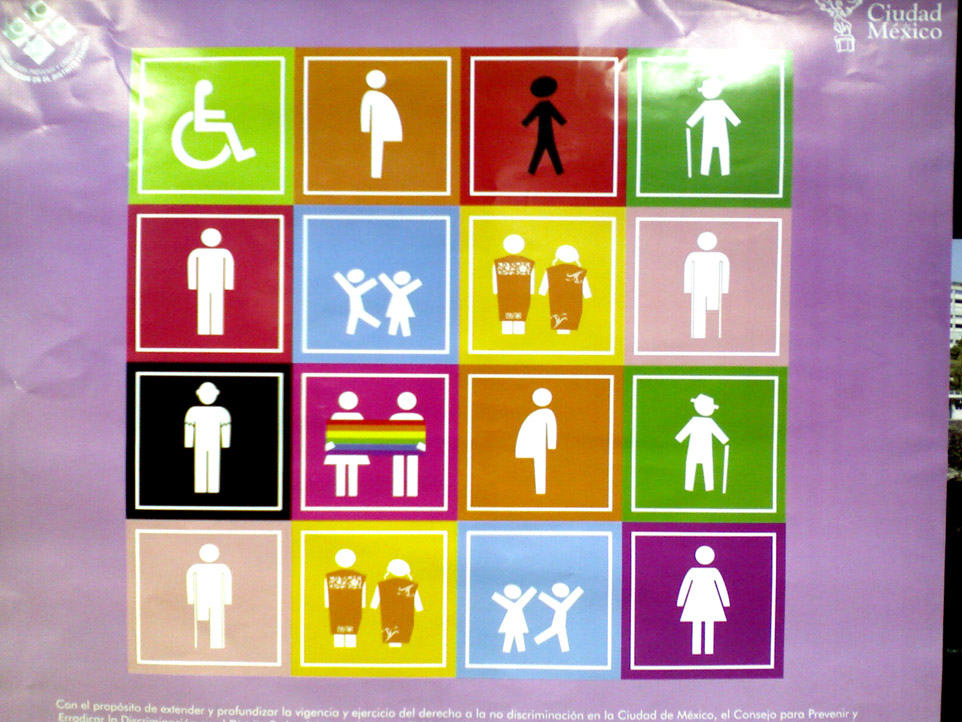

Figure 10-16: An advertising campaign against discrimination in Mexico City’s metro. Source: https://flic.kr/p/49e7q3 Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Dimitri dF.

Institutions

If we juxtapose Canadian and American SSM policy, an interesting difference emerges. It is clear that Canada is far more advanced in gay rights generally, with broad anti-discrimination laws, removal of criminal sodomy laws, and the legalization of SSM. However, this difference cannot necessarily be attributed to the success of the gay rights movements in changing public opinion on same-sex relationships. Public polling on this issue showed inconsistent public support measures for SSM or anti-discrimination measures, depending on question phrasing and the polling location. Most importantly, the United States did not show significantly higher levels of opposition to SSM than Canada. Attributing policy differences as largely a result of differing ideologies does not seem supported by polling evidence. How then can we account for the significant difference in the law regarding gay rights?

Smith (2005) suggests institutions can provide critical insight here. He uses historical institutionalism and path dependency to explain why the US and Canada diverge on SSM policies. He argues that the parliamentary government in Canada versus the institutionalized checks and balances in the US is an important explanatory variable. First, Canada’s laws on human rights are determined nationally by the federal government, whereas the US has to deal with a complex mix of federal and state governments. Therefore, Canada’s federally controlled criminal code allowed for the decriminalization of sodomy, and it took effect equally across Canada. The United States, on the other hand, has a patchwork of state, federal, and municipal laws, meaning that sodomy laws remained on the books in many jurisdictions much longer. It was not until 2003, with the Supreme Court decision of Lawerence vs. Texas, that criminal anti-sodomy laws were found unconstitutional. This is a difference of forty years. During the interim, laws criminalizing same-sex relations meant that policy discussions in the United States needed to contend with opponents who could more easily frame this as a moral issue. Conversely, in Canada, the removal of these laws criminalizing same-sex relations meant policy discussions are framed as a rights issue. This institutional difference allowed interest groups within each country different opportunities to pursue their policy objectives.

Second, Canada’s parliamentary system allows the federal government more space to act. Whereas in the United States, there are significantly greater checks on government authority. This is particularly true in a majority parliamentary government. Given strict party discipline, there are far fewer constraints on a government enacting policy, and far fewer opportunities for opposition forces to effectively oppose government policy. In stark contrast to this, in the United States, opponents to SSM could utilize the various referendum ballot initiatives and pass legislation at the state level as a means to further discrimination against LGBTQ folk and frustrate efforts to legalize SSM.

Figure 10-17: US and Canadian flags at the US Capitol. Source: https://flic.kr/p/ifhnmP Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Photo Phiend.

3. The Multiple Streams Approach (MSA)

The Multiple Streams Approach focuses on how, when, and why policy windows open, or might open, on LGBTQ policy and SSM in particular. Policy windows open when there is an alignment between a policy problem, an acceptable policy response, and the political will to apply it. The issue of SSM is challenging for the MSA. Take Canada and the US, for example. There was no overwhelming degree of public support for SSM in either state when legalization occurred. This makes political will difficult. Decisionmakers are hesitant to move forward on a policy if it is likely to exert a political cost. In Canada, the Liberal Government of Paul Martin paid a steep price to pass the ‘The Civil Marriage Act,’ losing a minister and taking a political hit from social conservatives. The Conservatives also paid a political cost when re-opening the debate on SSM in the House of Commons in 2006. And Andrew Scheer’s comments on issues like SSM and abortion came back to haunt him during the 2019 election. In the US, with a much greater influence of social conservativism in politics, the public is even more divided, and the cost of championing SSM is even higher. This is why MSA is less insightful here. The policy window opened, but it was not due to decision makers’ sustained attention or political will. In fact, decisionmakers likely wanted to avoid entering the quagmire of SSM debates at all since there was a lack of political will due to a lack of public opinion in support of SSM. Instead, the policy window was forced open by the courts both in Canada and the US. In Canada, the 2003 decision by the Ontario Court of Appeal and the opinion of the Supreme Court of Canada forced the window open. Despite earlier advocacy to legalize SSM in the US, the government either avoided taking a stance or actively opposed SSM, such as the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act. The path to legalization of SSM in the US via the Obergefell v. Hodges decision was much longer, more difficult and convoluted due to the number of jurisdictions involved and the number of policy entry points for opponents to fight it. But in both Canada and the US, the policy window was not politically driven. Rather, it was opened by activism and the courts.

Figure 10-18: A hammer, gavel, and scales. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/hammer-horizontal-court-justice-802298/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of succo.

4. Critical Perspectives

From a critical perspective, SSM is a core issue. It doesn’t take a critical approach to note that denying SSM is discriminatory and rooted in bigotry. However, applying a critical theory lens allows scholars to unpack the narrative of power, privilege, and coercion between the LGBTQ movement and the institutions of governance. This is a narrative of systemic persecution and discrimination. This is a narrative where someone’s essential nature, their sexuality, is criminalized. This is a narrative of fighting for fundamental human rights like equality, the right to love a partner of one’s choice, marry, and have children. Queerlaw has made an important contribution here. Queerlaw questions the absence of LGBTQ perspectives in politics and law-making and in other critical theory approaches such as some feminist and race scholarship. In terms of legal scholarship, Queerlaw looks at the role of narrative, privilege, power, and coercion, particularly in the definition and application of concepts like sex, gender, and sexual orientation. This approach challenges the typical binary understanding of these concepts. For example, Queerlaw scholars would challenge the idea that sex is binary since this excludes intersexuals. They also highlight the common conflation of sex, gender, and sexual orientation, as well as the legal implications of doing so. Further, they would unpack the historical basis and policy application of how sex, gender, and sexual orientation are applied and the coercive and discriminatory role this has played in the past and continues to play today. For example, Queelaw would unpack the tension between the courts and government in attaining SSM or, as is the case in many places of the world today, denying SSM. However, Queerlaw is not monolithic. In the case of SSM, some view this as a question of equality and of respecting the essential nature of same-sex couples. However, others are more critical of the goal of attaining SSM. They see marriage itself as a repressive institution, and the pursuit of SSM is a co-opting of the LGBTQ movement by mainstream institutions of privilege and patriarchy.

Figure 10-19: Lady justice peeks through her blindfold. Permission: Courtesy of course author Martin Gaal, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan, based on https://publicdomainvectors.org/en/free-clipart/Abstract-Rainbow-Stripes/39586.html and https://publicdomainvectors.org/en/free-clipart/Woman-with-justice-vague/68885.html

5. Comparative Public Policy

What would a comparative research program on SSM policy look like? SSM is a fascinating subject for comparative public policy research for a couple of reasons. First, it is a relatively new policy area, so there are many different things happening in different parts of the world. Second, it is universal – every country and culture in the world includes LGBTQ folk, making LGBTQ rights a global area of study. Third, SSM is an issue that interacts with different cultural and societal values in very different ways. Two interesting examples of comparative public policy on SSM include the role of institutions and norm diffusion.

As discussed in the institutional subsection of policy frameworks above, a comparison between Canada and the US is instructive. Canada and the US share many cultural markers. The two countries have many things in common. Historically, they share a similar settler colonial background. They have a complicated but deeply interdependent history, especially in the latter half of the 20th century. They have, for the most part, integrated their economies. They have strong cultural ties, especially in media consumption. They have military commitments with each other. There are important policy areas in which they differ, most notably social welfare policies. In terms of policy differences, one of the big explanatory variables is their respective political institutions. Canada has a parliamentary political system with a fused legislative and executive branch of government. The US has a presidential political system with an intentional diffusion of power, a robust system of checks and balances, and a very strong bias towards state rights. In practice, this means that when the Canadian government acts, it is quite unified, and its policies are national in context. On the other hand, the US is quite diffuse, with multiple points of entry into the decisionmaking process for a variety of stakeholders. There are numerous levels of government often acting in the same policy area. In the case of SSM, these institutional differences can explain a lot about the timing, the form and the function of the policy. Possible comparative research questions could ask how the institutional differences between two states, such as Canada and the US, influence the form and function of SSM policy debates? Other comparative questions could look at the role of the EU as an institutional structure between the Member States.

Another interesting comparative research agenda looks at how norms on LGBTQ rights more generally and on SSM, more specifically, have evolved in different contexts. Norm diffusion refers to the processes by which social expectations and the informal regulatory rules migrate. Norm diffusion can be seen in migration between polities both at a national and international level. For example, we can see norm diffusion in the national context as Ontario’s judicial and governmental decisions had a strong influence on the expectations of the behaviour of other provinces and the federal government. We can also see norm diffusion at the international level. The decision to legalize SSM in the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, and Canada created strong expectations that other Western Democracies would follow suit. However, we can also see norm diffusion in migration between policy areas. For example, norms on human rights influence norms on LGBTQ rights, which influences norms on SSM. These examples of norm diffusion offer several comparative research programs. For example, why has the US been more resistant to norm diffusion on SSM compared to Canada? Why is there greater norm diffusion between Western European states than Eastern European states within the EU? Or why have supposedly universal norms of human rights facilitated the legalization of SSM in some countries but not others?

Figure 10-20: American Pride flag. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/wall-brick-grafitti-window-rainbow-2794569/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Angela_Yuriko_Smith.

Watch the SBS Dateline video “What are the lessons from Ireland’s same-sex marriage vote” https://youtu.be/xcnLj7cpF08

*Please note that SSM has been legalized in Australia, Ireland, and Northern Ireland. This video was filmed prior to Australia’s legalization of SSM in 2017 and before the decision in the UK Parliament that forced Northern Ireland to legalize SSM in 2020.

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How would you describe the debate on SSM in Ireland?

- How would you describe the debate on SSM in Northern Ireland?

- From a public policy perspective, what are the pros and cons of using a referendum on SSM?

- Using the material from the video and the content in the module, propose a comparative analysis research project of SSM in Ireland, Northern Ireland, and Australia using either a stage (or stages) of the policy cycle or a Critical Perspective.

Conclusion

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the issue of legalizing same-sex marriage. We introduced the concept of same-sex marriage and some of its history. In particular, we looked at the debates in the United States, Canada, and to a lesser degree, the Netherlands. We noted that the debates over the legalization of same-sex marriage have two distinct narratives. On one side, some argue that the legalization of SSM is about equality and human rights. They argue that denying same-sex couples the same recognition given to other-sex couples is stigmatizing and has real-world implications. It legitimates discrimination and even persecution against those in the LGBTQ communities. On the other side, those who oppose the legalization of SSM argue marriage is an institution rooted in religious and cultural values. They fear that opening the institution of marriage to same-sex couples will degrade this institution. After examining this debate, we turned to our comparative public policy frameworks to understand the differential application of legalizing SSM in different jurisdictions. We noted that although the agenda-setting stage has been important for the LGBTQ rights movement, it was less influential in legalizing SSM. Instead, we noted the judiciary’s importance and the role that institutions have played in legalizing SSM. We closed with a look at how Queerlaw has deconstructed the use of sex, gender, and sexual orientation in creating and maintaining structures of privilege and power.

Review Questions and Answers

The debate over legalizing same-sex marriage has been deeply divisive in most countries. While achieving majority acceptance and broad institutionalization in many countries, SSM is still banned in others. More worrisome is that same-sex relations is still punishable in some states. The debate in the US frames the two sides of the debate quite well. On one side, those who favour the legalization of SSM are arguing that this is about equality and human rights. They are arguing that denying same-sex couples the same recognition given to other-sex couples through the institution of marriage, is to make their relationships of a second order. It stigmatizes LGBTQ folk and legitimates discrimination and even persecution. On the other side, those who oppose the legalization of SSM are arguing that this is about culture and identity. They are arguing that marriage is an institution rooted in religious and cultural values. They fear that opening the institution of marriage to same-sex couples will degrade this institution. Instead, they suggest that civil unions or other forms of recognition should be pursued.

President Bill Clinton, under pressure by Republicans and social conservatives, signed ‘The Defence of Marriage Act’ into law in 1996. It remained in effect until 2013 when it was struck down by the US Supreme Court in United States v. Windsor. It is a useful example of how social conservatives have attempted to block the legalization of SSM. DOMA defined marriage as exclusively between a man and a woman. Further, it mandated that those states that have banned SSM were not required to recognize SSMs performed in other jurisdictions. Following the passing of DOMA, more than 40 states passed legislation that explicitly banned SSM or amended their constitutions to do so. Further discrimination included the inability of a non-biological parent in a same-sex couple to adopt their child and support extended to other-sex parents to care for partners or children was excluded. The judicial invalidation of DOMA led to the overturning of Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015 and the constitutional right for SSM. DOMA is significant because it encapsulates the social conservative resistance to the legalization of SSM and the slow but inexorable path to legalization through the courts. It highlights the political, judicial, and cultural aspects of the SSM debate.

An important distinction between the US and Canada is their respective form of government – in other words, the institutions of their politics. Canada’s parliamentary system allows the federal government more space to act. Whereas in the United States, there are significantly greater checks on government authority. This is particularly true in a majority parliamentary government. Given strict party discipline, there are far fewer constraints on a government enacting policy, and far fewer opportunities for opposition forces to effectively oppose government policy. Canada’s laws on human rights are determined nationally by the federal government, whereas the US has to deal with a complex mix of federal and state governments. Therefore, Canada’s federally controlled criminal code allowed for the decriminalization of sodomy and it took effect equally across Canada. This began the institutional and judicial recognition of LGBTQ rights and the legalization of SSM. The United States, on the other hand, has a patchwork of state, federal, and municipal laws, meaning that sodomy laws remained on the books in many jurisdictions. In Texas, for example, sodomy laws remained on the books for 40 years after Illinois repealed their sodomy law in 1963.

. The retention of laws criminalizing same-sex relations meant that policy discussions in the United States needed to contend with opponents who could more easily frame this as a moral issue. Conversely, in Canada, the removal of these laws criminalizing same-sex relations meant policy discussions are framed as a rights issue. This institutional difference allowed for interest groups within each country different opportunities for action in pursuing their policy objectives.

Norms are social expectations and informal rules that regulate societal values and prescribe behaviour. Norm diffusion theory suggests that these societal values and the associated behaviour can spread both domestically and internationally as well as between issue areas. Norms and norm diffusion argues the acceptance and development of norms around human rights include LGBTQ rights. In turn, the acceptance and development of LGBTQ rights create a basis for, and the expectation of, legalizing SSM. We can see this in Canada, where advocates used the courts to define and expand on LGBTQ rights more generally and on SSM more specifically. However, we can also use norm diffusion theory to explain the diffusion of same-sex marriage debates throughout western democracies. In essence, an international norm influencing states to offer same-sex couples some sort of legal recognition developed, and it is the influence of this norm that led to the uptake of SSM policy in these different countries.

Queerlaw questions the absence of LGBTQ perspectives not only in politics and law-making but also in other critical theory approaches. This includes for example, some feminist and race scholarship. In terms of legal scholarship, Queerlaw looks at the role of narrative, privilege, power, and coercion, particularly in the definition and application of concepts like sex, gender, and sexual orientation. This approach challenges the typical binary understanding of these concepts. For example, Queerlaw scholars would challenge the idea that sex is binary since this excludes intersexuals. They also highlight the common conflation of sex, gender, and sexual orientation. They unpack the legal implications of conflating these concepts. Further, they would unpack the historical basis and policy application of how sex, gender, and sexual orientation are applied, as well as the coercive and discriminatory role this has played in the past and continues to play today. For example, Queelaw would unpack the tension between the courts and government in attaining SSM or, as is the case in many places of the world today, denying SSM. However, Queerlaw is not monolithic. In the case of SSM, some view this as a question of equality and of respecting the essential nature of same-sex couples. However, others are more critical of the goal of attaining SSM. They see marriage itself as a repressive institution, and the pursuit of SSM is a co-opting of the LGBTQ movement by mainstream institutions of privilege and patriarchy.

Glossary

Canadian Human Rights Act: is a statue of law created in 1977 that established a set of prohibited grounds for discrimination. These include race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, marital status, family status, genetic characteristics, disability, and conviction for an offence for which a pardon has been granted or in respect of which a record suspension has been ordered. Importantly for this module, sexual orientation was added in 1996.

Charter of Rights and Freedoms: was adopted with the patriation of the Canadian Constitution in 1982. It sets out the rights and freedoms of all Canadians, including fundamental freedoms, democratic rights, mobility rights, legal rights, equality rights, and language rights. Most important for this module is equality rights.

Civil partnership: or civil union, is a legally recognized relationship between two people and can confer many of the same rights and obligations of marriage.

Common-law relationships: is when two unmarried people live together in a relationship and share things like a home and financial obligations.

Defense of Marriage Act: is a piece of US legislation passed into law in 1996 and remained in effect until 2013 when it was struck down by the US Supreme Court in United States v. Windsor. DOMA defined marriage as exclusively between a man and a woman. Further, it mandated that those states that have banned SSM were not required to recognize SSMs performed in other jurisdictions.

‘Gay conversion’ therapy: is a dangerous practice that seeks to change an individual’s sexual orientation to heterosexual. It relies on pseudo-psychological and spiritual intervention.

‘Gay Liberation’ movement: is a political and social movement that emerged in the wake of the Stonewall Riots. It sought recognition of primarily gay and lesbian rights.

Human rights: as a concept in its contemporary form, refer to the universal and intrinsic rights everyone person holds by the fact of being born. As stipulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, these include human, civil, economic, and social rights.

Legalization: is the political process of removing barriers to some act or to granting public recognition of some act.

LGBTQ: is a collective acronym for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer communities.

Norm diffusion theory: suggests that societal values and the associated behaviour can spread both domestically and internationally as well as between issue areas.

Queerlaw: is a body of legal scholarship that questions the absence of LGBTQ perspectives not only in politics and law-making but also in other critical theory approaches. Queerlaw looks at the role of narrative, privilege, power, and coercion, particularly in the definition and application of concepts like sex, gender, and sexual orientation.

Same-sex marriage: is the marriage of two people with the same gender through a civil or religious ceremony.

Stonewall Riots: were a series of violent protests against over policing of the LGBTQ community in 1969 and began following a police raid at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village in New York City. The riots are often credited with the beginning of the process to mainstream the LGBTQ movement and are remembered in the Pride Parades that happen around the world.

‘The Civil Marriage Act’: is the legislation that legalized same-sex marriage in Canada.

References

BBC. 2019. “Why social issues are a hot topic in Canada’s autumn election.” British Broadcasting Corporation News, August 30, 2019. Accessed from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-49528267

Carroll, Aengus and George Robotham. 2016. The Personal and the Political: Attitudes to LGBTI People Around The World. Geneva: International Lesbian, Gay, Trans and Intersex Association, 2016. Accessed from: https://ilga.org/downloads/Ilga_Riwi_Attitudes_LGBTI_survey_Logo_personal_political.pdf

Curry, Colleen. 2017. “9 Battles The LGBTQ Community In The US Is Still Fighting.” Global Citizen, June 20, 2017. Accessed from: https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/9-battles-the-lgbt-community-in-the-us-is-still-fi/

Dabhoiwala, Faramerz. 2015. “The secret history of same-sex marriage.” The Guardian, January 23, 2015. Accessed from: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jan/23/-sp-secret-history-same-sex-marriage

Davidson, Robert J. 2020. “Advocacy Beyond Identity: A Dutch Gay/Lesbian Organization’s Embrace of a Public Policy Strategy.” Journal of Homosexuality, 67(1): 35-57. DOI: 10.1080/00918369.2018.1525944

Duncan, Pamela. “A history of same-sex unions in Europe.” The Guardia,. January 24, 2016. Accessed from: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2016/jan/24/a-history-of-same-sex-unions-in-europe

Eskridge, William N. The Case for Same-sex Marriage : From Sexual Liberty to Civilized Commitment. New York: Free Press, 1996.

Euro News. 2013. “Reflecting on 12 years of gay marriage in the Netherlands.” EuroNews, January 4, 2013. Accessed from: https://www.euronews.com/2013/04/01/reflecting-on-12-years-of-gay-marriage-in-the-netherlands

Felter, Clarie and Danielle Renwick. 2019. “Same-Sex Marriage: Global Comparisons.” Council on Foreign Relations, October 29, 2019. Accessed from: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/same-sex-marriage-global-comparisons

Georgetown University Law. 2020. “A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States.” Accessed from: https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=592919&p=4182205

Green, Emma. 2016. “America’s Profound Gender Anxiety.” The Atlantic, May 31, 2016. Accessed from: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/05/americas-profound-gender-anxiety/484856/

Harris, Elizabeth. 2017. “Same-Sex Parents Still Face Legal Hurdles.” The New York Times, June 20, 2017. Accessed from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/20/us/gay-pride-lgbtq-same-sex-parents.html

Kollman, Kelly. 2007. “Same‐Sex Unions: The Globalization of an Idea.” International Studies Quarterly, 51: 329-357. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00454.x.

Lipka, Michael and David Masci. 2019. “Where Europe stands on gay marriage and civil unions.” 2019. Pew Research Center, October 28, 2019. Accessed from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/28/where-europe-stands-on-gay-marriage-and-civil-unions/

Little, Simon. 2019. “1 in 4 Canadians still oppose full same-sex marriage rights: poll.” Global News, August 1, 2019. Accessed from: https://globalnews.ca/news/5713172/canadians-same-sex-marriage-rights-poll/

Masci, David. 2008. “An Overview of the Same-Sex Marriage Debate.” Pew Research Center. Accessed from: https://www.pewresearch.org/2008/04/01/an-overview-of-the-samesex-marriage-debate/

McCarthy, Martha. 2020. “How a Canadian case pushed along 20 years of progress in same-sex equality.” The Global and Mail, January 3, 2020. Accessed from: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-twenty-years-of-progress-in-same-sex-equality-started-with-a-canadian/

Paternotte, David. 2015. “Global Times, Global Debates? Same-Sex Marriage Worldwide.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 22(4): 653–674. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxv038

Perper, Rosie. 2020. “The 29 countries around the world where same-sex marriage is legal.” Business Insider, May 27, 2020. Accessed from: https://www.businessinsider.com/where-is-same-sex-marriage-legal-world-2017-11

ProCon.org. 2016. “State-by-State History of Banning and Legalizing Gay Marriage.” ProCon.org, February 16, 2016. Accessed from: https://gaymarriage.procon.org/state-by-state-history-of-banning-and-legalizing-gay-marriage/

Smith, Miriam. (2005). “The Politics of Same-Sex Marriage in Canada and the United States.” PS: Political Science & Politics 38(2): 225-228. DOI: 10.1017/S1049096505056349

Stack, Liam. 2016. “The Challenges That Remain for L.G.B.T. People After Marriage Ruling.” The New York Times, June 30, 2016. Accessed from: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/01/us/the-challenges-that-remain-for-lgbt-people-after-marriage-ruling.html

Stewart-Winter, Timothy. “Queer Law and Order: Sex, Criminality, and Policing in the Late Twentieth-Century United States.” The Journal of American History 102, no. 1 (2015): 61-72.

Waaldijk, Kees. 2001. “Small Change: How the Road to Same-Sex Marriage Got Paved in the Netherlands,” in Legal Recognition of Same-Sex Relationships in Domestic and International Law. Oxford: Hart Press, 2001.

Winston, Carla. 2018. “Norm structure, diffusion, and evolution: A conceptual approach.” European Journal of International Relations 24(3): 638–661. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066117720794

Zeitz, Josh. 2015. “The Making of the Marriage Equality Revolution.” Politico, April 28, 2015. Accessed from: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/04/gay-marriage-revolution-evan-wolfson-117412

Supplementary Resources

- Gallagher, Maggie, and Joshua Baker. Demand for Same-sex Marriage: Evidence from the United States, Canada, and Europe. 2006.

- Paternotte, David. "Global Times, Global Debates? Same-Sex Marriage Worldwide." Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society22, no. 4 (2015): 653-74.

- Pierceson, Jason, Adriana Piatti-Crocker, and Shawn Schulenberg. Same-sex Marriage in the Americas: Policy Innovation for Same-sex Relationships. 2010.