Developed by:

Dr. Martin Gaal – University of Saskatchewan

Overview

This is the last substantive module in the course, and the topic of health care is probably the most relevant issue to wrap up a comparative public policy course in Canada. Healthcare is a policy that defines much of the Canadian narrative, intentionally differentiating it from the United States. While previous issues introduced in this course, including environmental policy, immigration policy, and same-sex marriage policy, are all contentious with entrenched stakeholders on more than one side, health care policy is an essential part of how Canadians understand themselves.

In this module, we will define the field of healthcare as both the practice of medicine and the institutional structures that support its delivery. We will look at the constituent forms of the practice of medicine, in particular, what defines primary, secondary, and tertiary care. We will introduce the goal of health care established by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the institutional requirements to make that a reality. Next, we will look at the different typologies of healthcare systems. These typologies differentiate between types of healthcare systems based on healthcare provision, consumption, and technological research.

In applying our frameworks of public policy analysis, we will note the major healthcare issues on the systemic and institutional agendas in the US and Canada. We will look at the deep ideological determinants of healthcare policy, the entrenched interest groups that enable or constrain change and the impact of how healthcare has been institutionalized. We will explore the issue of political will in healthcare policymaking, particularly noting the dilemmas inherent in debates over the national pharmacare plan. In the section on critical perspectives, we will unpack the power, privilege, and coercion that has informed disparities for healthcare, noting in Canada the form this has taken for women and Indigenous peoples and the fiscal constraints that create burdensome wait times. Finally, like in our other modules, we will close with some suggestions for comparative public policy analysis in healthcare.

- Define the policy area of health care.

- Explain the typology of different health care models, including those from OECD (1987) and Moran (2000).

- Discuss why the institutional aspect of health care policy is so important.

- Critically assess and apply the tools of comparative public policy analysis to health care policy and related typologies.

- Healthcare

- Primary care

- Secondary care

- Tertiary care

- Pharmacare

- Welfare state

- Alma-Ata Health Declaration

- Reproductive health

- Typologies of health care systems:

- Source of funding (OECD 1987):

- National health service

- Private insurance model

- Social insurance

- Provision

- Families of health care states (Moran 2000):

- Entrenched command and control states

- Supply states

- Corporatist states

- Insecure command and control states

- Source of funding (OECD 1987):

- Single-payer system

- Acute care

- Affordable Care Act

- Individualism

- Supply

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

Burau, Viola, and Robert H Blank. “Comparing Health Policy: An Assessment of Typologies of Health Systems.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 8, no. 1 (2006): 63-76. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert_Blank3/publication/240521682_Comparing_Health_Policy_An_Assessment_of_Typologies_of_Health_Systems/links/556359b908ae8c0cab36eced/Comparing-Health-Policy-An-Assessment-of-Typologies-of-Health-Systems.pdf [Online link]

Learning Material

Introduction

One of the most important developments of the modern state in the 20th century, particularly in terms of public policy, has been the variety of entitlements and social policies designed to protect and ensure its citizens’ essential well-being. Collectively, these entitlements and social policies are known as the “welfare state.” In terms of its impact on a citizen’s life and the proportion of the budget involved, health care is one of the most critical policy areas. Physical and mental health is a vital part of a person’s well-being. That may seem common sense – without our health, we cannot enjoy those things that are important to us: our family, our friends, our work, and our hobbies. But in terms of public policy, health also has important spillover effects on society that need to be considered. Personal health correlates with productivity. Healthy children perform better at school. Better physical and mental health correlates with decreased policing costs and decreased social welfare costs. At the aggregate level, a healthy populace is better educated, more productive, thus supporting the economic conditions of an entire society. The healthcare system of any country is, therefore, critically important.

Figure 11-1: For most countries, healthcare costs occupy a large proportion of economic activity. Source: https://flic.kr/p/s6cDYe Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Pictures of Money.

For most countries, healthcare costs occupy a large proportion of economic activity. Governments are either directly involved in financing these systems or regulate the private interests that do. Healthcare costs are also increasing. Per capita, spending on healthcare increased in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) states between 1990 and 2009 by around 75% in real terms (OECD 2011). Two factors have largely driven this increase in costs. First, the most advanced economies have a markedly ageing population. An ageing population consumes a much larger amount of health care services in pure quantity and in proportion to the rest of the citizenry. Second, advancements in medical therapies, diagnostic capabilities, and medical procedures mean populations will likely continue to age. Therefore, there is a bit of a policy paradox here. Although increased spending on healthcare correlates with healthier societies, healthier societies create even more demands for health care spending. This paradox means that the spillover economic benefits of a healthy society may be eclipsed by the increasing costs of health care provision.

Another issue surrounding health care policy is the room for policy ingenuity. While the best indicator of a healthy society is per capita spending on healthcare, this is not always the case. Some countries spend more on health care per capita than others while still having worse health outcomes. This indicates there is room for policy entrepreneurship to maximize the efficiency of healthcare spending (OECD 2011). For these reasons, and the literal life or death implications of decisions made in this arena, health care policy is one of the most important public policy areas.

Therefore, policymakers working on the issue of healthcare have to reconcile a lot of tensions. What are the fiscal limitations on health care provision? What is the duty of care the state has for citizens? Who should be responsible for paying for health care provision or insurance? Where is the balance between efficiency and equity? Comparative public policy is one means to find the answers.

Figure 11-2: Policymakers working on the issue of healthcare have to reconcile a lot of tensions. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/health-disease-stethoscope-heart-5119702/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Before moving on, let us assess how much you know about health and health care systems

Take Quiz 1: Public Health Weeks 2019 https://blogs.biomedcentral.com/on-health/2019/04/04/quiz-public-health-weeks-2019/

Take Quiz 2: International Health Policy Quiz https://interactives.commonwealthfund.org/international-quiz/

On the following Padlet board, add a post with the following:

- Quiz 1 – Your Score out of 10

- Quiz 2 – What kind of Traveler you Are

- Were there any health answers that surprised you? If so, why?

- Were there any national health care answers that surprised you? If so, why?

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include:

- Your Padlet contribution

- The best Padlet contribution by one of your classmates and why you think this is a strong contribution

Healthcare: Levels of Care and Institutional Infrastructure

Healthcare as a policy area encompasses both medicine and the institutional structures that support its delivery. The practice of medicine concerns the research and delivery of therapies designed to maintain health through prevention, diagnosis, mitigation, or curing disease. The practice of medicine is typically divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary health care.

Levels of Health Care

Primary health care includes family physicians, walk-in clinics, and to a lesser degree, emergency departments. For some, primary care also includes other professional and licensed health practitioners such as physiotherapists, massage therapists, chiropractors and dieticians. An important dimension of primary care, especially in ageing populations, is the treatment, or the monitoring of treatment, for chronic conditions. In chronic but relatively uncomplicated pathologies, primary care providers can treat or manage the disease. In terms of best practices, primary health care seeks to establish continuity, which allows a holistic approach to health care, including routine checkups, preventative care, and a centralization of the patient’s health history. In the best-case scenario, the patient-doctor relationship exists from prenatal consultation to end-of-life decisions. It would also include doctors who advocate for their patients and monitor patient health in its totality.

Figure 11-3: From Birth to End of Life care. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/maternity-hospital-baby-mother-4331925/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of reginars9012015. |

Figure 11-4: From Birth to to End of Life care. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/hospice-care-patient-elderly-old-1821429/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of truthseeker08. |

There are limits to primary care medicine. When these limits are reached, primary care providers send their patients to secondary care and tertiary care. Secondary care includes medical specialists who have greater expertise in particular pathologies and treatments. For example, oncologists or cardiologists have spent considerable time and resources to undertake specialist training to treat cancer or heart conditions, respectively. Primary care doctors still play an important role in such treatments by monitoring their patient’s procedures, potentially coordinating different specialist interventions. This is particularly true for complex pathologies and treatment plans, often including chronic conditions. However, even secondary care has its limits. When even more intensive care is required, patients are referred to tertiary care. Tertiary care constitutes very specialized equipment and knowledge. Such specialized equipment and knowledge are normally only available in large regional hospitals, especially teaching hospitals. Examples of such specialists include hemodialysis or neurosurgery. Often, disease and treatment plans move between the various levels of care. For example, primary care physicians may monitor a patient for a chronic condition such as kidney disease. They may consider blood pressure or cholesterol medication. As the disease progresses, the patient may require secondary and tertiary care, including dialysis or even a kidney transplant.

Figure 11-5: MRI machine. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/mri-magnetic-resonance-imaging-2815637/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of jarmoluk.

Institutional Infrastructure

The World Health Organization produced the Alma-Ata Health Declaration in 1978 to establish the aspirational goal of health care as:

Any chance of achieving this aspirational goal requires the mass collection of personal information, the building of networks, the establishment of physical treatment centers, the training of qualified doctors, and researchers and technicians. In other words, to facilitate the practice of medicine, an institutional infrastructure needs to be in place. Such institutional support of medicine most often requires state-level organization, which in turn requires governments to consider a number of questions:

- What level of health care should be available to citizens?

- Who should pay for health care services?

- If the government is going to pay for all or part of health care provision, are there any limits on spending?

- Who is going to accredit, regulate, and monitor health care?

Take Canada, for example. Canada provides primary health care. But it does not provide universal coverage for vision, dental, or pharmacare. The government does provide some of these services for those people who are more precarious – but not everyone and not for all conditions. Further, while Canada has a national health-insurance program, the provision of healthcare is a provincial jurisdiction. That means that despite the federal basis of insurance, actual delivery varies between provinces. Take reproductive health, for example – while abortion is legal in Canada, access varies between provinces. In Prince Edward Island, it took the threat of a lawsuit in 2017 for abortion services to be made available. In Toronto or Saskatoon, this is not the case. There are also marked differences in healthcare services within provinces. For example, there is no access to abortion services north of Saskatoon. While these are extreme examples, the same logic is operative for basic health care services – the less affluent the province and the further away from a major city center, the quantity and quality of healthcare diminish. Canada, and many other states that provide universal health care, can also have long wait times for diagnostics like MRIs and for non-critical procedures like hip or knee replacements. This doesn’t have to be the case, but it is because of economic and political considerations. Take another example: Should the government pay for rare and life-threatening treatments, like Zolgensma, a 2.8 million dollar prescription for a deadly neuromuscular disease that affects babies? How many MRI scans or knee replacements could be performed for 2.8 million dollars? On what basis does the government make such decisions?

According to the definition of the Alma-Alta Healthcare declaration, Canada faces numerous other healthcare issues, including the inadequate provision of mental healthcare, treatment for addictions, and resources for the growing number of chronic conditions with an ageing population. In the next section, we will review the types of health care systems that governments can choose from to try to answer these questions and meet the expectations and needs of their citizens.

Figure 11-6: A man holds a sign reading “Health Coverage for All!” at a rally in support of the Affordable Care Act, Washington, DC, 2017. Source: https://flic.kr/p/SfRK4V Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Ted Eytan.

Watch the TED Talk ‘What if we paid doctors to keep people healthy?’ https://youtu.be/J3pGKt7fE-M

Note: while the video focuses on the US and the ‘fee for service’ model, Canada also utilizes the fee for service model. For background, see the following links:

- BC: https://www.policynote.ca/how-and-how-much-doctors-are-paid-why-it-matters/

- AB: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/health-care-physician-payment-cuts-report-1.5274521

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- a. Why does Müllenbeck argue that we have a ‘sick care’ system and not a ‘healthcare’ system?

b. What are the implications of this? - a. How does he propose a redesign of the healthcare system’s architecture?

b. What are the advantages and disadvantages of his suggestion?

c. What are the policy implications of his suggestion? - a. Müllenbeck closes with the suggestion this is not a question of technology but of vision and will. Do you agree or disagree?

b. What are the policy implications of your answer?

Types of Health Care Systems

Typologies are a useful way of thinking comparatively about policy between countries as they set out a framework of ideal cases that differ in significant ways from each other. They allow us to flesh out the definitions, scope, and boundaries of a field of enquiry. For example, we may create a typology of states that range from democratic, semi-democratic, semi-authoritarian, to authoritarian. Using these ‘types’ of states, we can sort countries into the appropriate box and research similarities and differences. When observing different health care policies, it is useful to apply a typology.

Typologies Based on Source of Funding (OECD 1987)

One of the older healthcare typologies was developed by the OECD at the end of the 1980s when many different OECD countries aimed to control government spending and reform their healthcare systems (OECD 1987). Accordingly, this typology focuses on different ways of funding healthcare systems and the implication for health outcomes. The basic funding dichotomy in healthcare policy is straightforward. Healthcare is either funded through government spending or private funding. These two funding arrangements are organized on a spectrum using two poles of corresponding values they promote: the equity of services received for patients within the system through government funding and the freedom of patients to access the care they choose through private funding. This also corresponds to how patients interact with the system, with more direct government control on the government-funded patient equity side and more market-based incentives on the private, patient agency side. The typology then has three ideal types of health care systems on this spectrum: a national health service towards the social equity pole, social insurance in the middle, and private insurance towards the patient sovereignty pole (see Figure 11-7).

Figure 11-7: Typologies of health care systems. Permission: Courtesy of Distance Education Unit, University of Saskatchewan.

A national health service is essentially a government monopoly on healthcare services. It is funded through government spending and aims to provide an equal level of healthcare to every citizen. A national health service model offers the most equitable access to healthcare but necessarily presents less choice for individual patients regarding the care they wish to receive. Diametrically opposed to a national health service model is a private insurance model. A private insurance model has for-profit insurance companies provide coverage for citizens. Healthcare services operate according to market forces, albeit highly regulated. This model gives patients the most choice in accessing the care they choose, but that choice largely depends on wealth, which presents basic challenges to equitable access to healthcare for all citizens. In between these two positions is social insurance. Social insurance involves less direct government control by providing equitable access to insurance, either government-run or by a non-profit group that is government regulated. Social insurance, therefore, ensures each citizen can access healthcare, with some mix of government-run and privately-run yet regulated hospitals.

While this model is dated, the focus the OECD typology has on ‘who’ funds healthcare is useful, as it captures one of the fundamental political debates behind health care policy – whether the market or government can better ensure optimal outcomes. More recent OECD models have expanded to consider another aspect of healthcare policy: the provision of healthcare. Again, this is on a familiar spectrum, from government-run to private care.

Figure 11-8: More recent OECD models have expanded to consider another aspect of healthcare policy: the provision of healthcare. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/puzzle-dna-research-genetic-piece-2500333/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of qimono.

Families of Health Care States (Moran 2000)

More complex typologies beyond the OECD have also developed as the comparative analysis of health care systems has grown. Moran’s (2000) typology is similar to the OECD model in that it captures the differences in institutions that govern the consumption of health care in systems. Still, like updated OECD models, it considers differences in the institutions that govern the provision or delivery of healthcare. Moran’s typology also includes a third aspect: the development of the technology of healthcare.

Moran’s typology has softer classification criteria and relies on qualitative judgement to identify where a state sits regarding their real-world healthcare system. This approach, therefore, produces “families” of health care states rather than a quantitatively defined typology. With that caveat, there are four important families of health care states in this ‘typology’:

- Entrenched command and control states

- Supply states

- Corporatist states

- Insecure command and control states

The form of the system adopted by the state has implications for the quantity, quality, and healthcare outcomes.

Entrenched command and control states are in the first family in the Moran typology. These states have healthcare institutions that are well established and have been so for some time. The state is a dominant force in the system. Regarding healthcare consumption, the state gathers the resources necessary for healthcare through taxation. It then distributes those resources throughout the healthcare system via state administration. Politicians control the larger decisions for the administration of healthcare. However, daily operations are delegated to professional planners and administrators. While there are some differences in administration through national or subnational governments (national, regional, municipal), the top-down planning model has the government, of some form, in control. The provision of health care is also mostly under government control, meaning that hospitals are publicly owned, and health care workers are public sector employees. However, some private control is normally present, often in the education of health care workers and in private associations controlling ethical practices. The production of technology is less constrained by the government, where private interests often control innovation in healthcare technology. However, given the immense power of the government over the consumption and the provision of healthcare and the needed interaction between the technology and the other two spheres, there are constraints on private interest power in developing technology. Moreover, some states invest in research and development, especially in disease research and things like vaccines. The United Kingdom and most Scandinavian states are typical examples of this sort of ‘entrenched command and control health care state.’

Figure 11-9: Signage at Horley Ambulance Station, part of the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS). Source: https://flic.kr/p/7GdoDe Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Christohper Paul.

Supply states are in the second family in the Moran typology. The term ‘supply states’ is used because, in each aspect of healthcare, the suppliers, rather than consumers, are the dominant actors in each field. Accordingly, in each of the three consumption areas, provision and especially technology, private interests reign supreme. Individuals are responsible for paying for their own healthcare, either directly or through private and often employer-linked insurance. Privately owned hospitals, staffed by privately employed health care workers, dominate the provision of healthcare. The development of technology is privately held and rampant throughout the system. The typical example of a ‘supply state’ in healthcare is the United States.

Figure 11-10: The typical example of a supply state in healthcare is the United States. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/cost-calculator-euro-dollar-money-4164541/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Corporatist states are in the third family in the Moran typology. In these health care states, the consumption aspect of healthcare is a blend of state and private control, as is the provision of healthcare. The primary funding source is social insurance, made by mandatory income-related contributions to non-profit insurance bodies from citizens. These insurance bodies act, according to law, as large corporations. The government enacts the role of director. Labour unions and business organizations act as partners. Healthcare provision works similarly, with hospitals operating under similar arrangements of a blend of private and government control. Compared to command and control states, the authority of the government is far more limited. Within this system, there are few constraints over the private development of healthcare technology. Germany is a typical example of a ‘corporatist healthcare state.’

Figure 11-11: A German ambulance. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vw_t4_v_sst.jpg#/media/File:Vw_t4_v_sst.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Sven Storbeck.

Insecure command and control states are in the last family in the Moran typology. These are essentially command and control healthcare states where the authority and control of the government are far from established in the consumption and provision aspects. These states are usually countries that have attempted to transition to command and control but have not overcome existing institutional arrangements. Private insurance providers may remain alongside a less secure and dominant government insurance system, and powerful interests from medical associations may also limit the power of the government to control hospitals and other elements of the provision of healthcare. Italy is an example of this sort of ‘insecure command and control state.’

Figure 11-12: An Italian ambulance. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/ambulance-emergency-services-italy-1639844/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Picudio.

Watch CNBC “How Canada’s Universal Health Care System Works” https://youtu.be/heK471H-s1s

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- What are the two narratives of Canadian health care in the US?

- Where do Canada and the US fall in each of the two typologies of health care systems given above?

- a. According to the statistics introduced in the video, how does the Canadian healthcare system compare to the US and other advanced economies?

b. How might the Moran typology explain some of these differences? - a. What is the derogatory term used in the US to explain the Canadian healthcare system?

b. What is the derogatory term used in Canada to explain the American healthcare system? - How might you use either of the typologies introduced above to compare the Canadian healthcare system to the US?

Applying the Frameworks of Comparative Public Policy Analysis

Much like we did in the previous module, we will now turn back to comparative public policy analysis frameworks to make sense of SSM. Recall the following frameworks from earlier modules:

- The Policy Cycle

- The roles of Ideas, Interest, and Institutions

- The Multiple Stream Approach (MSA)

- Critical Perspectives

- Comparative Public Policy

Let’s look at each of these more closely.

1. The Policy Cycle

Healthcare is a near-universal policy concern. The only places where healthcare is not an active policy concern are failed states, and even then, the concern for healthcare exists in the systemic agenda. Everyone, everywhere, at some time, is concerned about their health. On the institutional agenda of most states, healthcare policy is a perennial concern. Questions of costs, coverage, equity, and institutional structures are constants in policy debates. In this section, we will use Canada and the US as examples of healthcare policy debates. In both Canada and the US, we see the most pressing healthcare policy debates in the agenda-setting stage of the policy cycle.

The Agenda-setting Stage

In regards to healthcare policy in Canada and the US, there are debates on both the systemic and institutional agendas. In Canada, the debates on the systemic agenda cover a variety of topics. Canadian healthcare has many strengths. It is a single-payer system, so there are few fears that someone might go bankrupt over a medical procedure. Emergency, or acute care, receives high marks – people in urgent need are seen efficiently and receive quality care. However, many are left out of this supposedly universal health care system. For example, 57% of Canadians wait more than one month to see a specialist. For 15% of Canadians, they cannot find a primary care physician. Wait times for elective surgeries are commonly significantly longer than the OECD averages. The disparity by geography is even starker. Canadians in large metropolitan centers have access to healthcare that is quantitatively and qualitatively superior to rural and especially northern communities. Beyond physical healthcare, Canada has been facing a crisis in access to mental healthcare, again particularly in rural and northern communities, but also in socio-economically disadvantaged groups. There is also the issue of access to pharmacare. Canada is the only country with a universal health plan that does not have a national pharmacare plan. While most Canadians have some form of prescription coverage through their workplace, an average Canadian household still pays over a thousand dollars in out-of-pocket costs. Further, Canadians lack coverage for vision and dental issues. Finally, given the Federal versus Provincial jurisdiction for Indigenous healthcare, there is the inequity between indigenous and non-indigenous health access and outcomes.

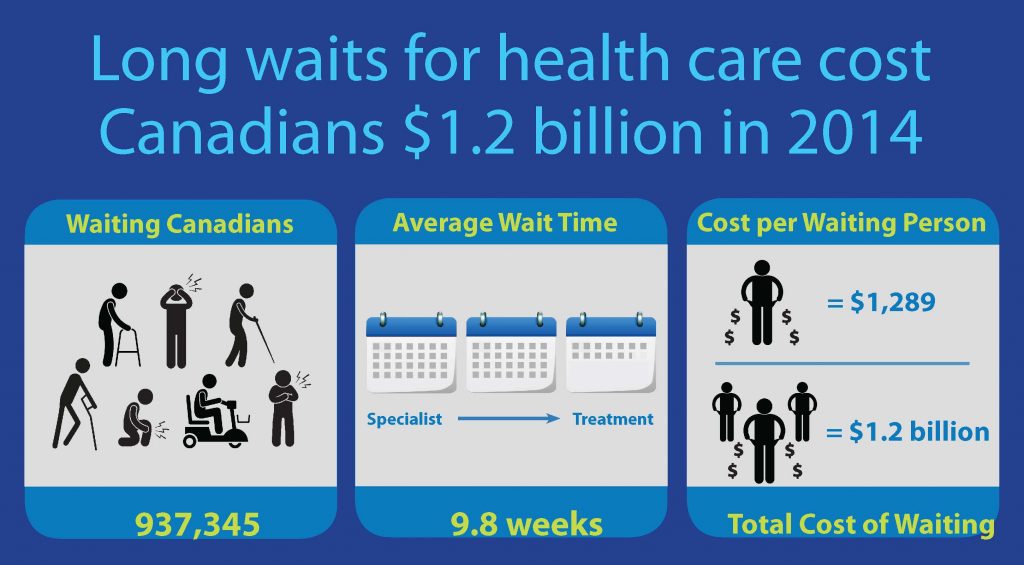

Figure 11-13: Infographic on wait times for Canadians. Source: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/file/private-cost-of-public-queues-2015-infographicjpg Permission: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Fraser Institute.

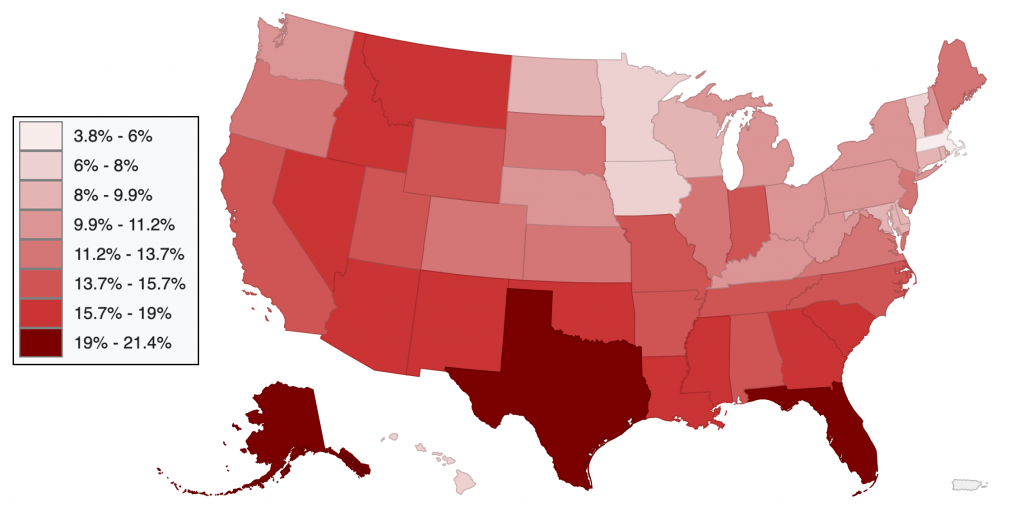

In the US, the biggest and ongoing healthcare crisis is the number of uninsured people. In 2010, 16% of Americans were uninsured, which is nearly 50 million people. That number dropped to 8.5% of Americans in 2018 due to the Affordable Care Act, or about 27 million people. However, there are also 27.5 million Americans who are underinsured. This means that even with ‘insurance,’ many Americans cannot access healthcare or still face crushing debt from accessing it when necessary. Beyond insurance issues, Americans face higher healthcare costs, both individually and at the aggregate level, for healthcare outcomes that are far below OECD averages. Those who are fortunate enough to have adequate healthcare insurance are often locked into health maintenance organizations (HMOs) that limit patient choices in terms of doctors, procedures, and types of medicine. Therefore, both Canadians and Americans have numerous issues on the systemic agenda competing for the attention of decisionmakers.

Figure 11-14: Percent of Americans uninsured (under age 65) by state (2014). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:United_States_Map_of_Percent_Uninsured_by_State_(2014).svg#/media/File:United_States_Map_of_Percent_Uninsured_by_State_(2014).svg Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Datawheel.

On the institutional agenda in Canada, there are a number of initiatives that range from a diabetes strategy to nursing in remote locations. In terms of institutional change, there are two items of particular note. The first is the idea of a national pharmacare plan. As argued earlier, Canada is the only state with a universal healthcare plan that doesn’t have a comprehensive pharmacare plan. Since the earliest debates on a healthcare plan, the idea of a comprehensive prescription drug plan has been debated, at least since the 1940s. In Canada, at least 25% of households have stated they cannot afford their medication. This leads to a worsening of health conditions when people stretch their medicine or go without it altogether. Approximately 70% of Canadians have private insurance through their employers, with over 100,000 different prescription drug plans providing different levels of coverage. Approximately 20% of Canadians have access to a public prescription drug plan, with differences between the provinces. Finally, Canada pays far higher prices for prescription drugs than the OECD average, largely due to the fragmented nature of coverage. While pharmacare has been debated for a long time in Canada, it largely remained off the institutional agenda until 2019, with only the NDP championing the case federally. When the governing Liberals faced the SNC/Wilson-Raybould scandal in early 2019, the government released the federal pharmacare report ahead of schedule and committed to instituting a national pharmacare plan. However, there are serious obstacles that cast doubt on the sincerity of this Liberal promise. There is the issue of jurisdiction, with the provinces likely to fight any federal effort to impose a pharmacare plan. There are entrenched interests, such as insurance companies and pharmaceutical companies, that stand to lose a considerable amount of money. However, perhaps most daunting is the countries current fiscal position in light of the COVID-19 crisis. All of this, especially in the context of other broken promises such as electoral reform, cast grave doubt on the likelihood of a national pharmacare plan becoming a reality.

Figure 11-15: Pharmacare in Canada. Source: https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-pills-on-container-3873163/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Polina Tankilevitch.

The other big healthcare issue on the institutional agenda in Canada is access to healthcare by indigenous peoples. Health care policy for Indigenous peoples with status is embedded in the Indian Act and is currently managed by Indigenous Services Canada. Indigenous peoples in Canada, at the aggregate, have far more obstacles to accessing healthcare and far worse health outcomes. The roots of these problems are embedded in the history of colonialism, the difficulties of geography, the complexity of jurisdiction, and the lack of culturally appropriate engagement. The history of colonialism has put Indigenous healthcare into the context of relocation, institutionalization, and coercion. For example, the experience of the Inuit who were forcibly relocated for tuberculosis treatment, often to poor quality hospitals. Even more egregious is the coercive practice of pressuring or forcing Indigenous women to be sterilized. Geography, reinforced by the remote location of reserves, makes access difficult when resources are not embedded locally. This distance breaks the bonds of primary care and is an obstacle to specialist care. It also requires much more time and money. For urban Indigenous peoples, physical geography plays less of a role than mental geography, which defines the expectations of both patients and practitioners. Take, for example, the case of Brian Sinclair, an Anishinaabe man living in Winnipeg who died of a bladder infection while waiting 34 hours in the emergency room at the hospital. Jurisdiction creates obstacles to care for Indigenous peoples by allowing many people to fall between the cracks of federal, provincial, and community-based healthcare programs and delivery. Finally, a history and continuing practice of healthcare ignores Indigenous culture and reinforces positionality between healthcare providers and Indigenous patients. For example, it is common for healthcare practitioners, who are in a position of authority, to undermine or devalue traditional medicinal practices. This creates a barrier to the acceptability of healthcare services, leading to healthcare needs going untreated. In response, the Liberal Government has promised to “ensure that Indigenous Peoples have access to the high-quality, culturally relevant health care and mental health services they need.” Again, it is still to be seen whether significant headway is made on this healthcare policy area.

Figure 11-16: Medicine Wheel. Source: https://www.picuki.com/media/2160434352302266650 Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

In the US, healthcare has been on and off the institutional agenda since the earliest day of the republic, as has resistance to any form of universal healthcare policy. In the early 20th century, as European states debated social welfare policies, the American Medical Association opposed any form of universal health care, warning it was a step towards socialized medicine. From the 1970s onwards, healthcare has been on the institutional agenda with proposals for major systemic initiatives or tinkering with existing policies. For example, in the 1970s, Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy worked on several proposals to introduce a single-payer, universal healthcare plan. In the 1990s, President Clinton pushed for a mandatory health insurance plan to guarantee affordability, albeit unsuccessfully. In the early 2000s, there were several attempts to adopt similar mandatory insurance programs. In the 2008 Presidential Election, McCain, the Republican candidate, and Obama, the Democratic candidate, proposed healthcare reform. As President, Obama tried to adopt a universal healthcare plan. However, he was stymied in his efforts by Republican opposition, especially in the Senate. The compromise was the Affordable Care Act (ACA, 2010), which sought to reduce uninsured Americans. It was partly successful in that the percentage of uninsured Americans was halved between 2010 and 2016 when Obama left office. However, the percentage of under-insured Americans did rise significantly. In President Trump’s first term, the ACA was attacked directly, by court challenges, and indirectly but by cutting funding, support, and undermining the requirement to have insurance. This brings us to the 2020 Presidential election, where healthcare has become a dominant issue. The two most significant aspects of this healthcare debate have been mentioned above: the number of uninsured or under-insured Americans and the cost of healthcare provision. In 2020, about 18% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was spent on health care. There are roughly 27 million people uninsured and another 27 million people underinsured in America, creating the potential for disastrous consequences if an urgent issue arises, like a car accident, heart attack, or cancer diagnosis. In polls, healthcare is a consistent policy concern for all voters. For more affluent and primarily conservative voters, there are fears that a universal healthcare plan would place a high tax burden on them. Others worry reform will limit their choice and access to healthcare or reduce the timeliness of access. Cumulatively, this makes healthcare a top policy issue in the next election. Democrats have proposed a range of healthcare reform during the primaries, from outright Medicare for all, a single-payer universal system, to reinforcing the ACA. The presumptive Democratic candidate Joe Biden was President Obama’s VP and has strongly suggested he would reinforce the ACA if elected. However, he faces pressure from more progressive elements in the party to go further towards a universal healthcare policy, notably senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. The Republicans are mostly focused on repealing the ACA, with a range of policies that give Americans more healthcare choice and more personal responsibility and risk and reduce public costs. These respective positions of the Democrats and the Republicans will frame the institutional agenda pertaining to healthcare following the 2020 election.

Figure 11-17: Trump 2020. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:TrumpPenceKAG.png#/media/File:TrumpPenceKAG.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Donald J. Trump for President, Inc. |

Figure 11-18: Biden 2020. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joe_Biden_2020_presidential_campaign_logo.svg#/media/File:Joe_Biden_2020_presidential_campaign_logo.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Biden for President. |

2. The Roles of Ideas, Interests, and Institutions

Ideas

Ideational factors are often constitutive of the forms of healthcare policies a state chooses. This is because healthcare policy represents more than the functional assessment and delivery of medical modalities. Healthcare is an emblematic part of the welfare state. It is based on, and representative of, the social contract, the rights and obligations we have to each other as citizens. For example, the deeply rooted individualism in the US is an important cognitive paradigm that shapes what is possible regarding healthcare policy. Lipset (1963) argues American individualism is most often explained by its revolutionary history. This individualism plays a big role in explaining why there is such resistance to state involvement in healthcare policy, especially if it constrains individual choice. Canada, on the other hand, puts less emphasis on the individual and more on the collective. Lipset argues this is rooted in Canada’s choice not to support the American Revolution and retain support for the monarchy, hierarchy, and traditional authority. These cognitive paradigms influence normative frameworks, which in turn shape the respective discourses on healthcare. In the US, this results in any challenge to private health care as a question of an attack on liberty. In Canada, this results in any challenge to public health care as a question of an attack on equality between citizens.

Figure 11-19: The engraving “Reception of the American Loyalists by Great Britain in the Year 1783”, depicts Loyalists seeking aid from Britannia following their expulsion from the newborn United States. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Britannia#/media/File:Reception_of_the_American_Loyalists.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Henry Moses.

Although healthcare policy in Canada and the US is deeply rooted in each state’s cognitive paradigms and normative frameworks, that does not mean there is no pressure for change. As we have seen in the United States, the universal healthcare policy option has existed on both the systemic and institutional agendas for a considerable amount of time. In the 2020 election, the Democratic party has staked part of its political platform to healthcare reform and increasing access and quality of care to more Americans. In Canada, the presence of long wait times for diagnostic tests and elective/non-urgent surgeries has put pressure on decisionmakers to open the public healthcare system for some private options. In the other direction, prescription drug coverage has created pressure for more public control of healthcare by demanding a national pharmacare plan. In each case, proponents and opponents utilize framing to shift the cognitive paradigms and normative frameworks. In the US, opponents to change frame public healthcare as ‘socialist’ or even ‘communist,’ linking resistance to the US Cold War struggle with the Soviet Union. This is juxtaposed with the current system defined by individual rights, individual choice, and freedom. In Canada, it is a diametrically opposite argument. Opponents to change frame private healthcare as ‘the corporatization of medicine,’ driven by profit over compassion. This is juxtaposed with the narrative that Canada’s public healthcare is a defining feature of Canadian identity, separating us from the US.

Figure 11-20: A sign at a 2011 Occupy Wall Street protest reads: “Obama is NOT a brown-skinned anti-war socialist who gives away free healthcare…you’re thinking of Jesus.” Source: https://flic.kr/p/asGx7f Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of David Shankbone.

Interests

Interests are perhaps the most significant predictor of who will act and under what conditions. As argued earlier in the course, ideas may define what you ‘should’ do and ‘why’ you should do it. But ideas by themselves rarely explain when some will act. Interests tend to do a much better job at predicting such questions. Individuals and groups tend to act when they perceive their interests to be under threat or an opportunity to advance their interests. In healthcare, there are a lot of interest groups that need to be taken in to account. At the broadest level, the citizens, or healthcare consumers, who expect that they will have the necessary access to quality healthcare. They expect access to primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare as needed. Beyond individual expectations, patients may form into advocacy groups for particular needs. For example, the Canadian National Institute of the Blind (CNIB) advocates for healthcare options on vision issues and provides programs and advocacy for the vision impaired. Myeloma Canada advocates for healthcare policy to address research/therapeutics for multiple-myeloma patients and raises funds for private research.

Figure 11-21: A CNIB guide dogs vehicle. Source: https://flic.kr/p/24iMmhN Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Mike Gifford.

Healthcare providers are represented by professional associations and are another interest group in healthcare. Some of these require membership to practice and maintain standards within professions like doctors, surgeons, and nursing. The largest of these organizations in Canada include the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, the provincial colleges of physicians and surgeons, and the provincial regulatory bodies for nursing, pharmacists, and dentists. There are also very powerful voluntary groups that advocate on behalf of their members, like the Canadian Medical Association, with 65,000 members. Some groups protect their members from lawsuits, such as the Healthcare Insurance Reciprocal of Canada (HIROC), which defend the hospital and nurses, and the Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA), which protects the doctors. To give an idea of their relative influence, these two organizations have a war-chest of nearly three billion dollars to defend and advocate on behalf of hospitals, doctors, and nurses. There are similar, albeit much larger, organizations that advocate on behalf of professional associations in the US.

Figure 11-22: Logo of the Canadian Medical Association. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CMA_AMC.jpg#/media/File:CMA_AMC.jpg Permission: Fair Use.

However, the biggest difference between Canada and the US is the next interest group: private health groups. Canada does have private interest groups that lobby decisionmakers on particular issues. According to a 2015 CD Howe Report, Canadians privately fund about 30% of healthcare spending, particularly prescription drugs, long-term care, dental, and vision. A large percentage of this private spending occurs through private insurance companies, most often provided by employers. These insurance and pharmaceutical companies have lobbied both the government and the general public to maintain the current private system. While the Liberal government has promised to act on a national pharmacare, there is a preference to increase insurance coverage versus adopting a single-payer system. This discussion in Canada about the pharmacare plan is very reminiscent of the debates in the US over changing the private healthcare plan to a public single-payer healthcare system, albeit at a minuscule scale in comparison. According to a report prepared by Health Canada, by the time a national pharmacare plan was fully implemented in 2027, it would cost 38.5 billion dollars. It would reduce the role of private insurance plans from a projected 19.8 billion to 3.2 billion dollars. Further, Canada pays some of the highest costs for prescription drugs out of the OECD countries, with only Switzerland and the United States paying more. A national pharmacare plan would shift the negotiating balance in favour of the government, threatening the profit margins of pharmaceutical companies. Both insurance companies and pharmaceutical companies have been aggressively lobbying against such a policy shift. However, the debate in the US dwarfs that of Canada. The US is a predominantly private 3.65 trillion dollar healthcare system. Nearly 785,000 companies are working in the American health sector, all for profit. One company, McKesson, is the largest healthcare company with annual revenue of 208 billion dollars. The healthcare industry employs 12.5% of the workforce. Most insured Americans are part of managed care plans that contract healthcare through networks of service providers, either Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) or Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs). These HMOs and PPOs also have a vested interest in debates on healthcare policy. Kaiser Foundation Health Plans, for example, owns 12 HMOs with over 6.5 million members. Finally, the Republican Party in the US has taken an ideological stance against ‘big government,’ especially under the influence of the ‘Tea Party,’ which pushes for sharp reductions in government spending. The size of the healthcare budget, the number of interest groups involved, the amount of profit at risk, and the ideological tinge to the debates make the fight over healthcare policy in the US a fierce battle between entrenched interests.

Figure 11-23: Health care reform law protests at the US Supreme Court, Washington, DC, 2012. Source: https://flic.kr/p/btFHZC Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Elvert Barnes.

Finally, it is useful to close with a more theoretical point when speaking of interests in policy debates. Is healthcare policy about self-interest or the public interest? The American discussion seems to be more centred on self-interest. The questions driving the policy debate are about the individual’s right to choose what is best for them. How much insurance do they want? How much can they afford? How much choice should they be allowed to have? What limits can or should be placed on individuals’ preferences? To what degree should medical care be driven by market forces? How much government resources, and therefore taxation, should be spent on healthcare? There is some debate on the public interest of expanding healthcare insurance coverage. And there is growing disquiet at the number of people left out of healthcare coverage. But the default position to be reckoned with is the individual and the market, not the public good. In Canada, the discussion is centred on the public good. There is a loose consensus that healthcare policy should not be market-driven, but rather it should be an equitable system that seeks the best health outcomes within given constraints. Some calls are to open the system to market forces, providing a private option on top of the public system. But the default position to be reckoned with is the universal and equitable concept that healthcare should be in the public good.

Figure 11-24: Community health worker graphic. Source: https://flic.kr/p/e28KB4 Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Simon Berry.

Institutions

The institutional approach to public policy has a lot of potential insight. The provision of healthcare is in and of itself institutionalized. Think of all that needs to be in place to provide primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare: educational systems, research systems, patient care networks, pharmacists, and all the regulatory oversight required to make these moving pieces work together. In Module 5, we introduced the three institutional theories of public policy: historical institutionalism, rational choice institutionalism, and sociological institutionalism. Each approach provides insight into healthcare policy development, but the first, historical institutionalism, is perhaps the most interesting. Historical institutionalism looks to the roots of the formal rules, compliance procedures, and standard operating procedures that define practices in a policy field. In other words, how can an appreciation of the historical background of a policy area make sense of its current form and function? In particular, those employing historical institutionalism look to historical contingency, path dependency, and critical junctures to understand the present. A comparison between Canada and the US is instructive here.

Sessions and Detsky (2010) argue that the healthcare systems in both countries were remarkably similar during the development of the modern welfare state in the late 1930s and remained so until the 1950s when the policy trajectories of the two countries began to diverge. Up until the 1950s, both countries had private healthcare systems. This included the provision and consumption of healthcare as well as research and development into healthcare technology. From the 1950s on, the policy paths of the two states began to diverge. The question then is what explains this shift in path dependency. Against commonly held beliefs, this shift in their respective paths was not the case of Canada deciding on government intervention and the United States favouring the system remaining private on all fronts. Instead, governments in either country made different choices on where government policy should direct resources, stemming from differing government capacities to act and different levels of strength from important actors in the policy field: the suppliers of healthcare, doctors, and medical researchers.

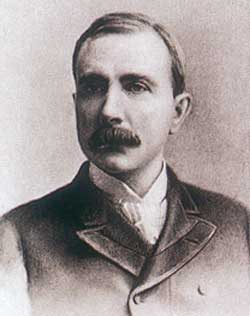

According to Moran (2000), in the United States, large philanthropic donations to medical research from wealthy business owners during the late 19th century meant that these suppliers were more powerful than their counterparts in Canada. In addition, differences between the more centralized government authority in Canada versus the decentralized authority in the United States meant that each government had differing capacities to overcome entrenched interests from healthcare suppliers. There was also an intentional and ideological resistance to ideas of collective consumption of healthcare in the United States that did not exist in Canada.

Figure 11-25: John D. Rockefeller, c. 1875. His targeted philanthropy through the creation of foundations had a major effect on medicine. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_D._Rockefeller#/media/File:John-D-Rockefeller-sen.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

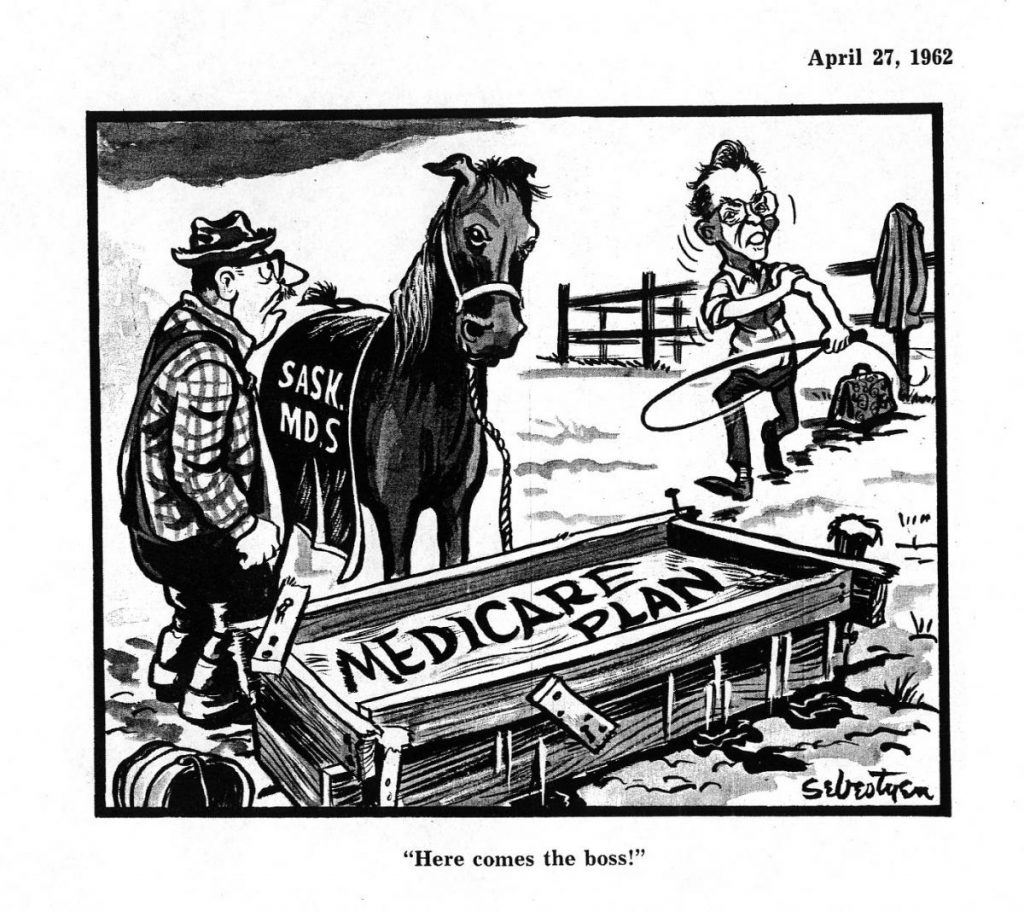

According to Moran (2000), the US Government chose to invest in the health care system provision and technology by building hospitals and funding medical research. The American federal government spent extraordinary amounts of money funding medical research through the National Institutes of Health, turning the US into a worldwide leader in high technology medicine. The US Government believed “medical research is the best sort of medical insurance.” These investments favoured suppliers over consumers, further empowering these actors and entrenching what would become a supply healthcare state. Healthcare consumption was largely left in private hands, as systems of non-government healthcare insurance linked to employers became the dominant source of funding. Canada, on the other hand, directed resources into government insurance models that supported equity of access. This was more beneficial to consumers. As the consumption aspect of healthcare policy developed, there was more need for government involvement in public insurance. Supplier interests resisted these changes in Canada, such as the Saskatchewan Doctor Strike of 1962. Still, their lack of power compared to suppliers in the United States and the comparatively stronger government in Canada meant they were unable to resist increased government control.

Figure 11-26: A political cartoon from 1962 depicts Premier Tommy Douglas as “the boss” brandishing a whip at the MDs of Saskatchewan. Source: https://www.saskarchives.com/Doctor_Strike Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

Sessions and Detsky (2010) posit that healthcare provision in Canada is not entirely held in government control as is in a ‘fully command and control healthcare state,’ as there are some concessions to supplier interests. However, government regulation in the provision of healthcare has meant that medical costs are under government control. In contrast, the United States developed no such constraints on the provision of healthcare. This has allowed providers to charge essentially whatever they chose. Moran (2000) argues this, in turn, encouraged further development and investment in lavishly expensive medical technology. While per-capita spending on healthcare is fairly well correlated with better health outcomes for most countries, the United States is an outlier where large expenditures on healthcare are not as closely associated with better health outcomes (OECD 2011).

In this brief overview of the historical development of healthcare policy in Canada and the US, we can discern institutional insights. In Canada, due to its more centralized authority and the decision to invest in consumption, healthcare policy diverged from privatized medicine towards public medicine. Due to the strength of medical suppliers and the ideological preference for strong liberalism, the US remains an outlier of OECD states with a private healthcare system. Within these institutional structures, we can see the role played by both rational choice institutionalism and sociological institutionalism. In Canada, the institutional structure means rational self-interested actors are more focused on the consumption side of healthcare. From the perspective of sociological institutionalism, we can see how this same institutional structure has come to define what the public, doctors, and government believe to be appropriate healthcare policy. It must be public and equitable. Anything else is a betrayal of Canadian values. In the US, the institutional structure means rational self-interested actors are more focused on the supply side of healthcare. From the perspective of sociological institutionalism, we can see a different logic of appropriateness at work. Instead of privileging public and equitable healthcare, it must privilege individual choice and market forces. Anything less is a betrayal of the founding fathers and the US constitution.

Figure 11-27: Signing of the United States Constitution. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scene_at_the_Signing_of_the_Constitution_of_the_United_States.jpg#/media/File:Scene_at_the_Signing_of_the_Constitution_of_the_United_States.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Howard Chandler Christy.

3. The Multiple Streams Approach

In the Multiple Streams Approach, we are looking at if and when a policy window might open. Policy windows are those moments when policymaking can happen. A policy window opens when three factors align: a recognized policy problem, a policy solution, and the political will to apply that solution. Policymaking on healthcare is a great example of why this can be so difficult. As discussed in this course, policymaking can be difficult, and the more transformative the change, the more difficult it is. Policy change challenges entrenched and powerful interests and mustering the political will to do so. In the last section, we noted that Canada could put in place a public healthcare system while the US was not. This policy divergence can be explained, at least in part, by the ability of the Canadian government to muster the political will to overcome the opposition of entrenched interest groups like healthcare suppliers and the inability of the American government to do the same.

In Canada, one of the biggest policy issues is the push for a national pharmacare plan. Dr. Steve Morgan (Morgan, n.d.) argues that a national pharmacare plan could save Canada up to 7.3 billion dollars. These savings would come from reducing drug costs by leveraging the negotiating power of one buyer representing the whole country and by decreasing the costs incurred from those who stretch or skip their medication because they cannot afford it. It would seem like a win-win situation. A national pharmacare plan could reduce costs and increases access. It is more equitable, which resonates with the narrative of the Canadian healthcare plan. It could increase positive health outcomes. It is not a radical proposal considering Canada is the only OECD country with a national healthcare plan but not a national pharmacare plan. Finally, it is not a new proposal. There has been a recommendation for a national pharmacare plan since the 1960s. So why has a national pharmacare plan not been implemented? There are a lot of potential reasons. There is a perception it would be expensive. There are vested and entrenched interests that oppose change. Remember, if the government implemented a national pharmacare plan by 2027, we would be talking about 38.5 billion dollars in spending. A national pharmacare plan would reduce private insurers, who currently control most prescription drug spending, to a minority player – cutting their share of that 38.5 billion dollars from 19.8 billion dollars to 3.2 billion dollars. Pharmaceutical companies also stand to lose significant profit margins from a national pharmacare plan. Looking at this through the lens of MSA, we can see there is a policy issue, and there is a policy solution. What is not there, or at least not yet, is the political will to implement it. Policymakers have to balance the potential costs against the potential gains, especially the political calculations. They need to do so knowing there are powerful interests that will seek to undermine them.

Figure 11-28: National pharmacare. Permission: Courtesy of course author Martin Gaal, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan, based on https://pixabay.com/photos/medical-treatment-pill-capsule-3308110/ and https://pixabay.com/photos/money-canadian-dollars-currency-4740120/

4. Critical Perspective

From a critical perspective, we want to look at the nexus of power, privilege, and coercion. We want to understand how the existing systems, institutions, and policies benefit some and harm others. More than anything, what is unique about a critical approach to public policy, is that we want to look for and listen to the voices not commonly heard. Who has been silenced, either intentionally or systemically? This pertains to every public policy area, but critically looking at healthcare is crucial. Who feels left out of healthcare? Who feels underserviced by the healthcare system? Who is actively harmed?

In terms of healthcare, there are a lot of ‘critical’ issues to address in Canada. We will briefly look at three very broad criticisms while acknowledging this is by no means an exhaustive list. As we have noted earlier, the most widely shared criticism of Canadian healthcare is wait times for non-urgent and/or elective procedures and diagnostics. Both Canadians and practitioners consistently identify wait times as a major problem in the healthcare system. And this is more than just an inconvenience. Wait times correlate with more severe disease pathologies, severe quality of life costs, and higher morbidity rates. In other words, wait times cost lives. The question from a critical perspective is not technical – how can we provide more healthcare resources. The question is why there is a systemic shortfall of healthcare resources. One of the answers is that rationing healthcare is one way that the government can control costs. A critical take on the Canadian healthcare system might ask why the cost is determining healthcare choices? A more nuanced question may ask how spending is being divided between healthcare issues? What are the spending priorities? In other words, who is being privileged and who is being left out.

Another critical take on the Canadian healthcare system speaks to this question of who is being privileged in the system – gender and healthcare. Women in Canada face more obstacles to accessing healthcare than men. Women are more likely to work in jobs with less healthcare coverage than men. This means that women are less likely to have insurance coverage, which puts a gender focus on the fact that Canada is the only OECD country without a universal pharmacare plan. Women are more likely to be stay-at-home parents and single parents, which also means they fall through the insurance gap. The privatization of healthcare issues has also burdened women more than men. When chronic or long-term care has been shifted away from public supports, women are often forced to fill the gap at home. This includes everything from dealing with childhood mental health issues to caretaking for elderly family members. More directly, privatization has shifted more women’s issues, especially around reproductive health. Women experience longer wait times for diagnostics and medical procedures than men. And finally, there is less money and research put into women’s health issues than men’s health issues. Again, from a critical perspective, the question is, who decides to prioritize what and why?

Finally, the issue of Indigeneity and healthcare is a big issue from a critical perspective. We discussed this earlier, but it is worthwhile mentioning it again here. We noted that Indigenous peoples’ access to healthcare, and the quality they receive when they do, is highly problematic. Indigenous peoples in Canada face more barriers to access healthcare than non-indigenous people do. The ongoing impact of settler-colonialism has created resistance to accessing healthcare due to history and continuous practice of coercion and harm. Healthcare is often seen as another institution of oppression. A lack of cultural sensitivity reinforces this perception. The result is a reluctance to access care and more severe pathologies, and worse outcomes. Geography is a problem due to the reserve system in Canada, which makes getting to healthcare providers difficult and expensive. This is even more true for secondary and tertiary care. The complex jurisdictional mix of federal, provincial, and community healthcare creates many gaps that Indigenous people fall through. Urban Indigenous peoples, who may not face all of these obstacles, still have demonstrable examples of systemic discrimination in accessing healthcare and healthcare quality when accessed. A critical approach is a useful way to dig into these issues. Where does power in the system lie? How does this contribute to the obstacles of Indigenous access to quality healthcare? How can things be changed to give voice to those who are less represented in healthcare? How can greater equity be achieved?

Figure 11-29: A woman receives a mammogram. Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/SMxzEaidR20 Permission: Public Domain. Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

5. Comparative Public Policy

What would a comparative research program in healthcare look like? Healthcare is such a broad policy area that the options are almost limitless. Healthcare policy deals with everything, from training students to health outcomes. Here are some examples of traditional comparative public policy projects on health care. There has been a lot of work using the typologies of healthcare states. For example, how does a national health service, social insurance, or private insurance model compare to cost? How do they correlate with indicators of health outcomes? A similar question could be asked about Moran’s ‘families’ of healthcare states?

More common is to compare two different states in terms of their healthcare policies. For example, you could examine the processes of healthcare policy development: why did Canada adopt a public model while the US adopted a private healthcare model? You could compare cost: which states, of similar economic development, provide the best health outcomes? How do they accomplish this? Or conversely, which states, of similar economic development, provide the worse health outcomes? You could look at subsections of healthcare policy and comparatively assess access to prescription drugs. You could comparatively examine the impact of different healthcare policies on worker productivity or quality of life indicators. From a critical perspective, you could assess the equity of different healthcare systems and the impact on different communities.

In the end, the choice of a comparative study is to find at least two systems, processes, or impacts that allow the researcher to explain something that provides insight into healthcare.

Watch the following videos:

CNBC “How Germany’s Universal Health Care System Works” https://youtu.be/1d3QLPdHysc

CNBC “How the United Kingdom’s Health Care System Works” https://youtu.be/45PfRLntfBU

CNBC “How French Health Care Compares to the US System” https://youtu.be/MHzUCToycks

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- What distinguishes the American health care system from:

- Germany?

- The UK?

- France?

- Using the material from the videos and the content in the module, propose a comparative analysis research project of healthcare between the US, Germany, the UK, and France using either the Ideas/Interests/Institutions framework or the MSA framework.

Conclusion

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the issue of healthcare. We introduced the definition of healthcare and unpacked its constitutive elements, including the provision of medicine and the institutional structures that enable this provision. We introduced and examined the typologies that have tried to make sense of different forms of healthcare policy. We looked at the dominant healthcare issues on the systemic and institutional agendas in Canada and the US. We unpacked the ideas, interests, and institutions that have shaped the form and function of healthcare policy and applied this to Canada and the US. In terms of political will, we examined the attempt to achieve a national pharmacare plan in Canada. We looked critically at the inequities within the Canadian healthcare system, especially for women, Indigenous peoples, and the impact of fiscal constraints on wait times.

Review Questions and Answers

Healthcare as a policy area encompasses both the practice of medicine and the institutional structures that support its delivery. The practice of medicine concerns the research and delivery of therapies designed to maintain health through the prevention, diagnosis, mitigation, or the curing of disease. The institutional structures of healthcare support the deliveries of medicine and requires state-level organization. In response, states can choose to control the provision and funding of healthcare. Or they can choose to allow the market to control the provision and funding of healthcare. Or, finally, they can choose something in between, where provision of healthcare is wholly or partially private and consumers of healthcare are protected by some form of mandatory insurance.

One of the older healthcare typologies was developed by the OECD at the end of the 1980s. At this time, many different OECD countries were aiming to control government spending and reform their healthcare systems. The typology then has three ideal types of health care systems on this spectrum: a national health service towards the social equity pole, social insurance in the middle, and private insurance towards the patient sovereignty pole. A national health service is essentially a government monopoly on healthcare service. It is funded through government spending and aims to provide an equal level of healthcare to every citizen. A national health service model offers the most equitable access to healthcare, but necessarily presents less choice for individual patients regarding the care they wish to receive. Diametrically opposed to a national health service model is a private insurance model. A private insurance model has for-profit insurance companies provide coverage for citizens. Healthcare services operate according to market forces, albeit highly regulated. This model gives patients the most choice in accessing the care they choose, but that choice is largely dependent on wealth, which presents basic challenges to equitable access to healthcare for all citizens. In between these two positions is social insurance. Social insurance involves less direct government control by providing equitable access to insurance, either government-run or by a non-profit group that is government regulated. Social insurance, therefore, ensures each citizen can access healthcare, with some mix of government-run and privately-run yet regulated hospitals.

Moran’s typology has softer classification criteria and relies on qualitative judgement to identify where a state sits regarding their real-world healthcare system. This approach, therefore, produces four “families” of health care states rather than a quantitatively defined typology.

- ‘Entrenched command and control states’ is the first family in the Moran typology. These states have healthcare institutions that are well established and have been so for some time. The state is a dominant force in the system. Regarding healthcare consumption, the state gathers the resources necessary for healthcare through taxation. It then distributes those resources throughout the healthcare system via state administration. Politicians control the larger decisions for the administration of healthcare. However, daily operations are delegated to professional planners and administrators.

- ‘Supply states’ is the second family in the Moran typology. The term ‘supply states’ is used because, in each aspect of healthcare, the suppliers, rather than consumers, are the dominant actors in each field. Accordingly, in each of the three areas of consumption, provision and especially technology, private interests reign supreme. Individuals are responsible for paying for their own healthcare, either directly or through private and often employer linked insurance. Privately owned hospitals, staffed by privately employed health care workers, dominate the provision of healthcare. The development of technology is privately held and rampant throughout the system.

- ‘Corporatist states’ is the third family in the Moran typology. In these health care states, the consumption aspect of healthcare is a blend of state and private control, as is the provision of healthcare. The primary source of funding is social insurance, made by mandatory income-related contributions to non-profit insurance bodies from citizens. These insurance bodies act, according to law, as large corporations. The government enacts the role of director. Labour unions and business organizations act as partners. The provision of healthcare works similarly, with hospitals operating under similar arrangements of a blend of private and government control. Compared to command and control states, the authority of the government is far more limited. Within this system, there are few constraints over the private development of healthcare technology.

- ‘Insecure command and control states’ is the last family in the Moran typology. These are essentially command and control healthcare states where the authority and control of the government are far from established in the consumption and provision aspects. These states are usually countries that have attempted to transition to command and control but have not overcome existing institutional arrangements. Private insurance providers may remain alongside a less secure and dominant government insurance system, and powerful interests from medical associations may also limit the power of government to control hospitals and other elements of the provision of healthcare.

Healthcare as a policy area is by definition institutionalized. Institutions, both formal and informal are a requirement for the provision of primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare. They require educational systems, research systems, patient care networks, pharmacists, and all the regulatory oversight required to make these moving pieces work together. In module five, we introduced the three institutional theories of public policy: historical institutionalism, rational choice institutionalism, and sociological institutionalism. Each approach provides insight into the development of healthcare policy, but the first, historical institutionalism, is perhaps the most interesting. Historical institutionalism looks to the roots of the formal rules, compliance procedures, and standard operating procedures that define practices in a policy field. In other words, how can an appreciation of the historical background of a policy area make sense of its current form and function? In particular, those employing historical institutionalism look to historical contingency, path dependency, and critical junctures to understand the present.