Developed by: Dr. Martin Gaal – University of Saskatchewan

Overview

In Module 3 and Module 4, we introduced two of the three elements that were argued to be important mutually constitutive elements of the policy environment:

- Institutions: both formal organizations and the informal patterns of rules, norms, and practices that shape the behaviour of actors

- Interests: a wide range of forces that create contextual frames that motivate individuals and organizations to be deliberate and act in particular ways.

- Ideas: both conscious and sub-conscious frames that shape beliefs and subsequently constrain or facilitate new ideas as policy solutions.

In Module 3, we introduced the concept of ideas, how ideas play a role in public policy and the case of Canadian Middle Power internationalism as evidence of an ideational influence in public policymaking. In Module 4, we introduced the concept of interests, how interests play a role in public policy, and the case of Canadian environmental interest groups as evidence of the role interests play in public policymaking. In each module, the goal was to demonstrate the respective influence of ideas and interests. It was not to argue that either was the only or even most important means to understand the process of public policymaking. In fact, we noted that in the case of Canadian Middle Power internationalism, it might be difficult to completely isolate the variables of ideas and interests as they arguably mutually constitute one another. Similarly, in the case of Canadian environmental interest groups, it is possible to see how their ‘interests’ were at least in part shaped by ideational factors such as their identity as environmental groups. Again, we must highlight this mutually constitutive relationship.

Figure 5-1: The White House at night, 2011. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_White_House_at_night,_2011.jpg#/media/File:The_White_House_at_night,_2011.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Rob Young.

In this module, we will be turning to the last of the three concepts, institutions. We have already seen traces of institutional impact in our previous two modules. We glimpsed the role of institutions in Module 3 when we examined the role of programmatic ideas in responding to the 2008 financial crisis. The responses by governments worldwide were largely similar, based on shared ideas of the best response. But these ideas were formed and implemented through institutions. In Module 4, we discussed the interaction between interest groups and the government. While interests largely defined this interaction, institutions played a role in structuring it. Therefore, in this module, we will be turning to the concept of institutions.

Institutions are discernible in almost everything we do individually and collectively. Institutions can most generally be seen as structures that shape what we do and how we do it, and some argue even why we do it. They create and sustain norms, rules, and procedures that both formally and informally constrain and enable particular behaviour.

Most formally, things like Parliament Hill in Ottawa or the White House in the US physically embody institutions. These are physical manifestations that represent respective institutional forms of government. These brick-and-mortar institutions represent different ways in which politics happens. It is where laws are made and enforced, and even what defines questions of justice and the ‘good life.’ Formal institutions set out required rules and procedures, for example, in the legislative process.

There are also informal institutions at play. Most informally, institutions constitute relatively stable expectations of behaviour. These are the unwritten rules that we almost instinctively follow. In our personal lives, this can be as simple as walking on the right side of the hallway in the university. This informal rule mirrors the way we drive on the road and, in practice, facilitates the flow of students rushing between classes. What is important to note is that this is an unwritten ‘rule’ and is not punishable. But it is discernible: most people adhere to it, and when they do not, others notice and may cast disapproving looks. The same logic happens in public policymaking. For example, while not legally specified, Canada has a convention that the Governor-General must appoint as PM the party leader most likely to command a majority in the legislature. This is not a law, but it is an institutional norm that has been so internalized that it acts like one.

Figure 5-2: Governor General Mary Simon. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mary_Simon_GG_Announcement_2.png Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of Heartfox.

|

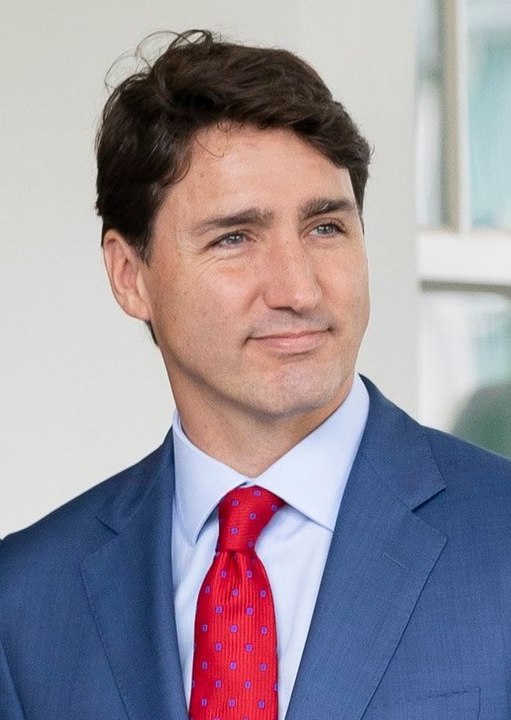

Figure 5-3: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trudeau_visit_White_House_for_USMCA_(cropped).jpg#/media/File:Trudeau_visit_White_House_for_USMCA_(cropped).jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of White House. |

In order to address the role of institutions in comparative public policy, we will first define the concept of an ‘institution.’ We will then look at three models that operationalize the concept of institutions in public policy analysis:

- The first approach is historical institutionalism, which argues that context has a determinative role in the institutional formation and, therefore, deeply informs its subsequent form and function.

- The second approach is rational choice institutionalism, which argues that institutions set structural boundaries within which decision making happens. Further, it argues these structural elements can influence the preferences of actors, shaping their self-interested behaviour.

- The third approach is sociological institutionalism, which argues the cultural context deeply influences institutions. These culturally derived institutions shape contextual expectations of appropriate behaviour.

Taken together, these three approaches set out the formal and informal ways that institutions shape the process and outputs of public policymaking. Finally, we will close with a case study of Canadian pubic policy on LGBTQ rights.

Figure 5-4: Canadian LGBTQ flag. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canada_Pride_flag.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Keepscases.

However, as suggested in both Module 3 and Module 4, we need to be careful not to overemphasize the role institutions play in public policy vis-à-vis ideas and interests. As we have demonstrated in the last two modules in many ways, these three variables of public policy are mutually constitutive. However, as we did in Modules 3 and 4, we are going to isolate one of these three variables, institutions, and look at the role they play in the public policymaking process.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define the concept of ‘institutions’ in public policy.

- Critically analyze the dominant theories that utilize the concept of institutions in public policy analysis, including historical institutionalism, rational choice institutionalism, and sociological institutionalism.

- Critically analyze the form and function of Institutions in comparative public policymaking.

- Assess the role institutions have played in LGBTQ public policy in Canada

- Describe, using examples, the mutually constitutive relationship between ideas, interests, and institutions.

- Ideas

- Interests

- Institutions

- Norms

- Formal structures

- Informal structures

- Historical institutionalism

- Critical juncture

- Historical contingency

- Path dependency

- Rational choice institutionalism

- Preferences

- Collective action problems

- Transaction costs

- Individual rationality vs. Group rationality

- European Integration

- Sociological institutionalism

- Logic of appropriateness

- LGBTQ rights:

- Dangerous sexual offender

- Stonewall Riots

- Everett Klippert

- Bill C-150

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

Walsh, James. “How Power And Institutions Affect Development”. World Economic Forum, 2015. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/03/how-power-and-institutions-affect-development/. [Online link; for Learning Activity 5-3]

Hutt, Rosamond. “This Is The State Of LGBTI Rights Around The World In 2018”. World Economic Forum, 2018. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/06/lgbti-rights-around-the-world-in-2018/. [Online link; for Learning Activity 5-4]

Learning Material

Introduction

We intuitively know that our lives operate within structural constraints. Our days are ordered by obligations and routines, from studying and working to our relationships with friends, family, and significant others. There are formal constraints, like clocking in at work, and informal constraints, like staying in touch with those who are important to us. We ignore these constraints at our peril. Doing so comes with potentially drastic consequences: from losing a job to losing friendships. In each case, there are formal and informal sets of rules, norms, and processes at work that set standards of appropriate behaviour. These sets of rules, norms, and processes, in turn, constitute institutions. In public policy, just like our own lives, there are formal and informal institutions at work.

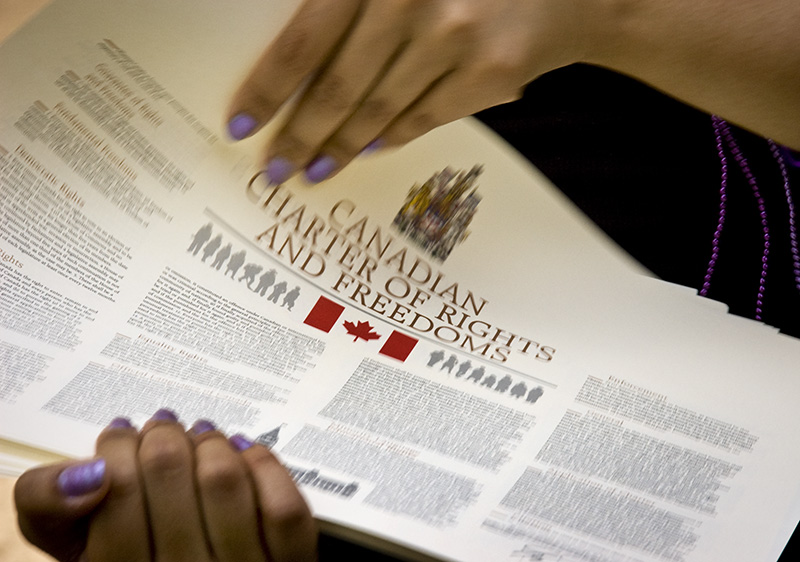

Most formally, there are institutional structures that specify how a state may create and enforce laws. This is highly formalized in states like Canada and the US, with the rules specified in a written constitution. In other countries like the UK, there is an unwritten constitution that is derived from common law. However, in each case, there is a formal, stable, and durable set of norms, rules, procedures that specify how laws are drafted, passed, and enforced.

Figure 5-5: The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Every_Canadian_Needs_A_Copy.jpg#/media/File:Every_Canadian_Needs_A_Copy.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Marc Lostracci.

More informally, institutional structures are not written down or even legally enforceable but still play a formative role in public policy. For example, there is a convention in Canada that the Senate should not defeat a bill passed by the House of Commons. It is argued that since the House is elected while the Senate is not, it would be less democratic for the Senate to defeat a House bill. It is instructive that the Senate broke this convention in 1989 over an abortion bill. While legal, this decision by the Senate was highly controversial and demonstrated, through its breach, the influence of the convention. This module argues that both formal and informal institutions play a significant role in public policymaking.

The module will begin by defining the concept of an institution, distinguishing between the formal and informal institutions, and highlighting the role they play in the public policy cycle.

In the next section, we will look at three approaches to utilizing institutions in public policy: historical institutionalism, rational choice institutionalism, and sociological institutionalism. Each approach recognizes the importance of the structural role that institutions play in public policy.

Finally, we will close with a Canadian public policy on LGBTQ rights.

Before moving on, I want you to think of a one-word answer to each question:

- What is a physical symbol of a government institution?

- What is a public policy that seems to have uniquely Canadian characteristics?

- What is a formal institution that constrains government policy ambitions?

- What is a norm that constrains government policy ambition?

Post your answer for each question on the following Padlet board. On this board, you can also “upvote” / “downvote” posts that you agree or disagree with.

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include:

- Your Padlet contribution

- The Padlet contribution by one of your classmates and why you think this is a strong contribution

What are Institutions?

In the broadest sense, institutions in public policy are akin to structures: they enable or constrain particular policy paths. Think of a building with floors, stairs, hallways, doors, and rooms. If we want to go to the classroom on the second floor of the building, we need to navigate its structural elements: go through the front door, walk up the ramp, walk down the hallway, and enter the door to the classroom. It would not be impossible to climb a tree instead and jump through the window of the classroom. However, doing so would be highly inefficient and would entail great personal risk. Institutions play a similar role in public policy that the building plays in navigating the pathway to our classroom: they enable or constrain how we act.

Figure 5-6: Usask Arts Building Overpass. Source: https://flic.kr/p/kgJuoG Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of daryl_mitchell.

We find the clearest evidence of institutional impact in public decision making in the formal structures. This is evident if we review the policy cycle:

- At the agenda-setting stage, a key distinction is made between the systemic agenda (those items being discussed in the wider body politic) and the institutional agenda (those items formally recognized by the government). This is an example of a structural constraint on public policymaking. The government has the right to include or exclude what will be considered and subsequently acted upon.

- At the policy formulation stage, bureaucracies within particular ministries will be tasked with drafting potential policy responses to items on the institutional agenda. These policy options are then put in front of policy decision-makers for consideration.

- At the policy adoption stage, some combination of the executive and legislative branches have the option to draft, debate, and pass a policy response or choose to do nothing.

- At the policy implementation stage, a variety of government bureaucracies, agencies, and civil servants will be tasked with translating legislation into practice.

- Finally, in the evaluation stage, administrative and judicial procedures will assess whether a policy is constitutional, whether a policy has achieved its stated aims, and whether it has done so efficiently.

At each stage of this policy process, there are procedures, ministries, and bureaucracies that have been formalized through law and practice. At each stage, we find formalized institutional structures that shape the path of public policy decision-making, much like how the building shaped how we get to the classroom.

Figure 5-7: UK Parliament in Session. Source: https://flic.kr/p/8NZwVq Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of UK Parliament.

However, institutions also have informal structures that shape the public policy process. If we think again of the building and class analogy, the formalized aspects of public policy decision making are the physical constraints – the doors, the hallways, the ramps, and the stairs. But how we navigate that space is often deeply influenced by less formalized institutional structures. Whether we hold the door open for others, whether we walk on the right side of the ramp or the hallway, where we sit in the class – these are all influenced by socially driven norms: perceived standards of acceptable practice that are often derived through group interaction over time. While less formal than the walls and doors, these socially derived norms are clearly discernible – they shape our behaviour. We can also clearly discern less formalized institutional structures in the public policymaking process. Every collective of people, from a friend group to a country, have socially derived norms. These norms are deeply influential at a conscious and subconscious level, enabling or constraining our behaviour as individuals and collectives. These norms set expectations of appropriate behaviour. Importantly, these expectations are also dependent on context. Our friends often have a set of expectations that differ from our parents, our elders, our professors, and our spiritual advisors. If you hold a particular role, that too will shape expectations of appropriate behaviour. People will have different expectations of you as a person than as a police officer, doctor, professor, or Prime Minister. While these expectations are certainly ideational and cognitive and linked to the role of ideas, they can also become structural – they can become institutions if they harden over time. Just as informal socially derived institutions shape how we navigate the formal structure of the building, they also shape decisions on appropriate public policy. Therefore, it is important to define formal and informal institutions before looking at the application of institutions in comparative public policy in the next section.

Figure 5-8. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/stairs-silhouettes-human-upward-70509/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Traditionally, the concept of ‘institutions’ in public policy analysis refers to established political organizations. These would include the state/government, legislatures, courts, the executive branch, bureaucracies, to name a few. These are things that we would intuitively associate with government and policymaking. Indeed, if asked, most people would point to an institution or at least the building that symbolizes its existence. Canadians would likely recognize Parliament Hill and would equate it to the institution of the Federal Government. This is the “I know it when I see it” approach to institutions.

Figure 5-9: Parliament Hill. Source: https://flic.kr/p/YusBPZ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Dennis Jarvis.

However, in order to operationalize the concepts of institutions in comparative public policy, we need a more precise definition. In academia, most definitions focus on regular patterns of behaviour that are shaped by rules, norms, practices, and relationships. This would include our analogy of the building with its doors, ramps, hallways, and rooms. It would also include our analogy of how we navigate that building, including holding the doors for others, walking on the right side of the ramp, and where we sit in the classroom. Douglas North (1990) defined organizations as “groups of individuals bound by some common purpose to achieve objectives” and an institution as “any form of constraint that humans devise to shape human interaction.” Elinor Ostrom (2005) provides a more detailed definition of institutions that focuses on their character and where such institutions emerge: “broadly defined, institutions are the prescriptions that humans use to organize all forms of repetitive and structured interactions including those within families, neighbourhoods, markets, firms, sports leagues, churches, private associations, and governments at all scales.”

Figure 5-10. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/hand-united-together-people-unity-1917895/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of truthseeker08.

These differences in language may seem trivial, but they highlight divisions within the discipline. Institutions present as a fixed entity or set of rules that we can all point to and understand in the same way. Yet, it is not inevitable that institutions will endure over time. It is not certain that institutions represent shared meaning for all people. Institutions may be reproduced in different ways by individuals who understand those rules and act differently. This makes the identification of institutions very tricky. Ostrom (2005) says, “institutions exist in the mind of the participants and sometimes are shared as implicit knowledge rather than in an explicit and written form.” This suggests that informal institutions may run counter to formal institutional rules when practice deviates from intentions established in the past.

Therefore, as Margret Levi (1997) argues, institutions can be defined as “the formal and informal rules, regular patterns of behaviour and the rules and norms that influence and structure political behaviour.” In comparative public policy analysis, institutions, therefore, often focus on formal institutions. This raises such comparative questions as to how the differences between a federal versus a unitary state, or a parliamentary versus presidential system respectively explain policy choice. For example:

- A federal state is more likely to face political battles over jurisdictional boundaries than a unitary state since a federal state has more diffuse power centres and more access points for interest groups.

- In a parliamentary versus a presidential system, the fused legislative and executive branches of government in the former and the explicit separation of powers in the latter may explain differences in policy coordination.

Figure 5-11. Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/lobbying-blackmail-business-161689/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of OpenClipart-Vectors.

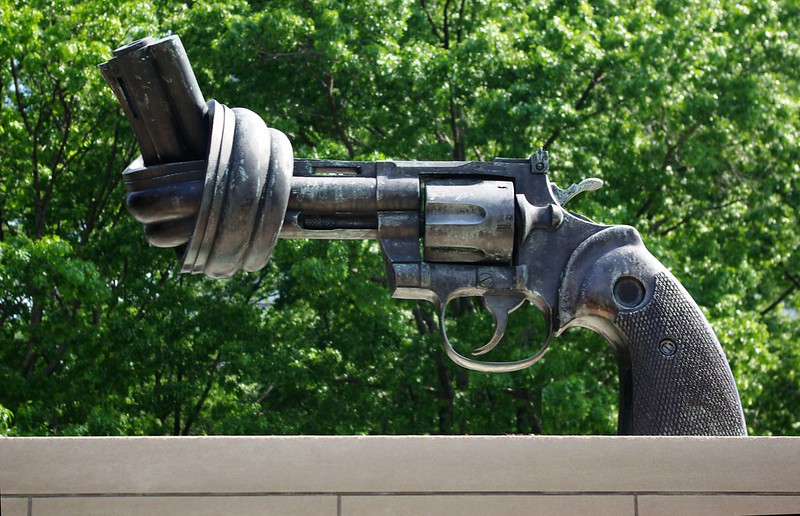

However, according to Levi’s definition, institutions also include the processes and norms that govern relations between the government and its agencies. These are often argued to be the ‘rules of the game’ that set actors’ expectations and therefore constrain and enable how we navigate the space of public policy. For example, in health care or gun control, the expectations of policymakers in the US and Canada are wildly divergent despite having the same overarching goals – the security and prosperity of their respective constituents. Therefore, it is important to note that both the formal and informal elements of institutions offer important insight when undertaking comparative public policy analysis.

Figure 5-12: “Non-Violence” (a.k.a. “The Knotted Gun”) by Fredrik Reuterswärd. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/alanenglish/532519876/ Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Al_HikesAZ.

Watch “What are social institutions?” by Economic Geography Group Heidelberg: https://youtu.be/XNVVHMVET20

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

1. What is a social institution?

2. How does it compare to formal institutions?

3. a.) Provide an example of both a social and formal institution in your life.

b.) How do they shape what you do and how you do it?

4. How does this provide insight into the process of public policymaking?

Institution-Based Approaches in Public Policy Analysis

All institutional approaches to public policy analysis share a focus on political structures. They all believe that these political structures shape, constrain, and enable political processes, decision making, and, ultimately, the form and function of policy outputs. They also all lend themselves to comparative public policy analysis. Institutional approaches allow us to ask whether different institutional arrangements and institutional norms could play a meaningful role in policy deliberation, policy construction, policy outputs, and the impact of policies once implemented. In this section, we are going to look at three important institutional approaches:

- historical institutionalism,

- rational choice institutionalism, and

- sociological institutionalism.

1. Historical Institutionalism

In historical institutionalism, institutions are treated as formal rules, compliance procedures, and standard operating procedures that structure conflict or shape behaviour and outcomes. The core premise of historical institutionalism is that decisions that are taken at the formation of an institution shape its future trajectory and shape the policy outputs associated with the institution. The key terms associated with the historical institutionalism approach are:

- historical contingency,

- path dependency, and

- critical juncture.

Let’s look at each of these in more detail.

Historical contingency refers to the idea that past events and decisions contribute to forming institutions that influence current practices. For example, the Canadian parliamentary system is historically contingent on the role of British colonization in North America, whereas the US presidential system is historically contingent on the American Revolution. Each event fundamentally shaped its respective institutional arrangements. In Canada, the long period of British colonial practices, the slow devolution towards independence, and the degree of continuity between British rule and Canadian independence, were fundamental to the form and function of Canadian parliamentary institutions. In the US, the perceived tyranny of the British led the framers to institutionalize a robust system of checks and balances in drafting the US presidential system.

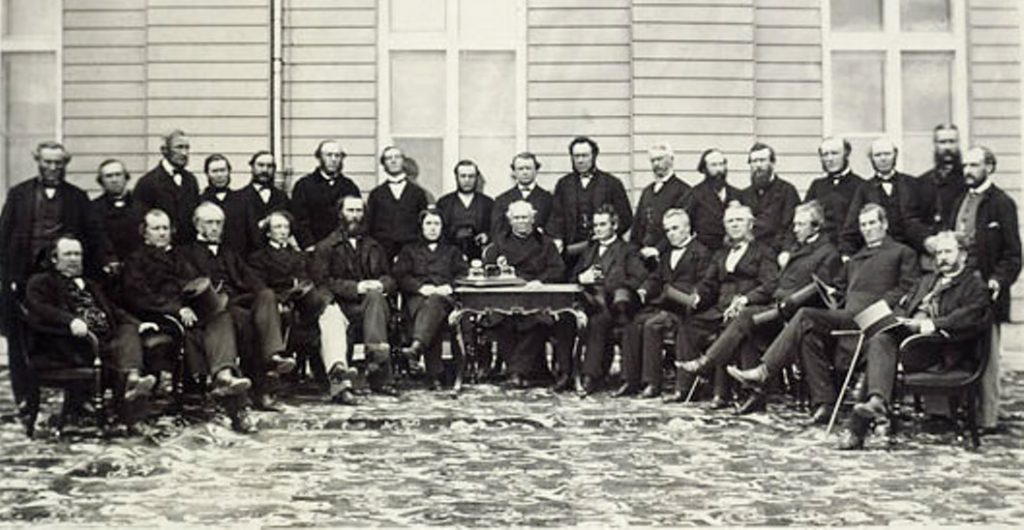

Figure 5-13: Signing the US Constitution, 1787. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scene_at_the_Signing_of_the_Constitution_of_the_United_States.jpg#/media/File:Scene_at_the_Signing_of_the_Constitution_of_the_United_States.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Howard Chandler Christy – The Indian Reporter. |

Figure 5-14: Negotiating Confederation, Quebec, 1864. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:QuebecConvention1864.jpg#/media/File:QuebecConvention1864.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Jules-Isaïe Benoît. |

Path dependency suggests that institutions, once constituted, exert pressure towards continuity and against change. This is because a lot of effort and resources go into creating an institution. Further, once operational, institutions require more time and more resources. In reaction, individuals and groups subsequently organize themselves around the form and function of these institutions. This makes the prospect of fundamental change risky for decision-makers: they will be opposed by those who benefit from an existing institution; they will be held responsible for the consequences of institutional change; they will potentially need significant resources to draft, pass, and implement new institutional structures; the consequences of policy change are unknown. For example, in the 2015 Federal Election, then-Liberal candidate Justin Trudeau stated he was “committed to ensuring that the 2015 election will be the last federal election using first-past-the-post.” However, between June 2015 and February 2017, the Trudeau Government went from promising electoral reform and establishing an all-party committee on electoral reform to explore options to defending the Liberals from accusations of partisan politics, wavering on the recommendation of proportional representation, and finally abandoning electoral reform altogether. This is a near-perfect explanation of path dependency: Trudeau makes a campaign promise, encounters fierce opposition, becomes wary of the proposed policy change, and is brought back into conformity with the existing policy path.

Figure 5-15. Source: https://flic.kr/p/LM6iFE Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Laurel L. Russwurm

Finally, the concept of critical juncture is also important to historical institutionalism as it helps explain institutional change – historical contingency and path dependency privilege institutional structure and, therefore, continuity. For example, historical contingency led to Canada inheriting the parliamentary system of government from the UK. Part of that inheritance included the first-past-the-post electoral system, and, as we previously discussed, path dependency has made changing that electoral system difficult. Critical junctures are moments when uncertainty or indeterminacy opens a window for agency, potentially for institutional change. Essentially, critical junctures are moments when changing the trajectory of a policy path is possible. Thinking back to the 2015 election, Trudeau’s Liberals were in 3rd place, polling behind the NDP. Electoral reform was a pet project of the progressive left and Trudeau pledged electoral reform as a means to win votes from the NDP. There had been rising interest in electoral reform, as evidenced by four referendums on the topic in BC, PEI, and Ontario. This was a potentially critical juncture – support for the current system was weakening, the election provided motivation, and Trudeau promised action. Ultimately, however, agency was trumped by structure in this instance.

Figure 5-16: Electoral Reform Protests in Ontario. Source: https://flic.kr/p/RRKDNp Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Ryan Hodnett.

The wider lesson for comparative public policy is that significant institutional differences are likely to be present in different countries. These institutional differences may be explainable, in whole or in part, by critical junctures, historical contingency and subsequent path dependency. It is important to note that minimal differences in initial conditions may result in significantly different outcomes over time because of divergent trajectories. Therefore, to fully understand current institutions and policy differences between countries, there is utility in looking to the past to establish how and why they developed. There is utility in comparing differences in conditions, processes, and outcomes. Historical institutionalism, therefore, provides a lens through which to understand policy change/continuity and policy variation within and across countries. It also provides comparative lessons that can be used for actors looking for insight into potential policy change.

2. Rational Choice Institutionalism

We discussed rational choice theory in the previous module, which aims to explain aggregate political outcomes with reference to the choices of individuals pursuing their self-interested preferences under particular conditions. Rational choice institutionalism adds another layer to this conversation. Rational choice theory posits actors seeking to maximize their self-interested preferences in an open or relatively open system. The main substantive constraints in this system are other rational actors pursuing their self-interested preferences. On the other hand, rational choice institutionalism posits these actors as bounded by institutional norms, rules, and procedures within which they compete with other egoistic actors.

According to rational choice institutionalism, institutions can address collective action problems and in particular, the issue of transaction costs:

- Institutions may solve a collective action problem when there is a difference between individual rationality and group rationality. For example, while there collectively may be a benefit in preserving a common resource, individually, there may be a benefit in overutilization. We introduced this previously when discussing interests, rational choice theory, and the ‘tragedy of the commons.’ Institutions may address such collective action problems by providing a forum where actors interact, cooperate, and find solutions to common problems.

- Institutions also reduce ‘transaction costs.’ In economics, institutions represent a set of formal and enforced rules governing relationships between individuals or organizations. The aims are to maintain the trust required for them to reach agreements and reduce the likelihood that agreements between actors will be broken. This reduces uncertainty and decreases the costs associated with wasted effort on joint tasks that are not fulfilled.

However, from a rational choice institutionalist perspective, it is important to note that once constituted, these institutions frame how an actor seeks to achieve their preferences. A common area of research that applies rational choice institutionalism to collective action problems is environmental policy.

Figure 5-17. Source: https://flic.kr/p/31rfxU Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Carlos

Rational choice institutionalism has been fruitfully applied to explaining European integration through the European Union. It is argued the post-war world created a collective action problem for European states. Faced with increased economic, political, and security threats, European states began to build institutions that would allow them to leverage their combined economic, political, and security resources. European integration began with six states forming the European Coal and Steel Community in 1952 based on intragovernmental cooperation to foster peace and economic growth. It has evolved into the European Union. The EU currently has 27 Member States, now that the UK has left the union. Without the UK, the EU collectively has a population of 447 million people. It is the second-largest economy in the world and the largest market. It is also the world’s largest international development actor. This has given the EU a weight and actorness that the individual Member States would have struggled to have alone. Institutionally, the EU is constituted by a mix of supranational and intergovernmental institutions that deeply shape the decision making on Member States’ economic, political, and social public policies. From the perspective of rational choice institutionalism, the Member States have agreed to integration because it solved a collective action problem. Member States believed they could be more secure, prosperous, and agential acting together than acting alone. The EU, therefore, provides the institutional structure to overcome the conflict between individual rationality and collective rationality. However, once constituted, Member States have had to adjust their strategy to achieve their preferences. Moreover, as the EU has continued to integrate, its influence has spilled over into an increasing number of policy areas: from economic policy to political policy, to encroaching on social policy. Therefore, while a state like the UK may have agreed to join the European integration project in 1973, the reach of the EU has extended considerably, leading to anti-EU sentiment in parts of the country. The UK government and its citizens have had to grapple with a cost-benefit analysis that weighs policy independence against the economic, political, and security benefits of UK membership in the EU. From this, we can see how rational choice institutionalism interacts with actors’ preferences both in creating institutions and operating within institutions once constituted.

Figure 5-18: European Parliament, Strasbourg. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:European_Parliament_Strasbourg_Hemicycle_-_Diliff.jpg#/media/File:European_Parliament_Strasbourg_Hemicycle_-_Diliff.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Diliff.

3. Sociological Institutionalism

While recognizing the more formal role of institutions, sociological institutionalism questions the utility maximization assumptions or consequentialist logic that underpin rational choice institutionalism. Instead, sociological institutionalism suggests that institutions are less a function of efficiency concerns and more a function of culture and a logic of appropriateness. From this perspective, institutions represent a relatively stable set of norms, rules, and procedures that are rooted in the contextual practices of specific groups of people. Once constituted, these culturally informed institutions shape how actors interpret the world and inform appropriate ways to act within it. One way institutions shape interpretations and inform behaviour is by defining the appropriate ‘role’ of actors within particular contexts. For example, we expect the Prime Minister, a professor, a doctor, or a judge to act in ways appropriate to that role. Further, we expect the Prime Minister to act differently when interacting with constituents and when acting with foreign dignitaries. And, in turn, those who hold such roles perceive these expectations and tend to internalize them into their own identities. Therefore, institutions not only constrain and enable what actors can do, but they also deeply influence perceptions and preferences of what actors should do. If deeply internalized, this influences what actors believe to be appropriate, good, and right. This suggests an important insight of sociological institutionalism: institutions once constituted are more than the preferences of the actors who created them.

Figure 5-19. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/woman-face-identity-self-me-i-am-510480/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of johnhain

From a sociological approach, institutions can solidify over time and will resist change. This is important in that it fosters stability, durability, and continuity. For example, when a new Prime Minister takes office, they are embedded in governmental institutions that are in many ways bigger than the person or party in power. These governmental institutions not only define what can be done legally, they inform what is appropriate to do and the appropriate way to do it. The PM and government will have their policy agenda and will try to make their mark on the country. But even their policy agenda has already gone through the particular institutions of the Canadian electoral system, regional/sectoral institutional bargaining, and the institutions of party politics. Ultimately, unlike rational choice institutionalists who emphasize the structural and constraining features of institutions, sociological institutionalism emphasizes institutions’ social and cognitive features. As such, this approach tends to explore where preferences come from and how they are generated.

Figure 5-20. Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/cranium-head-human-male-man-2099128/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of GDJ

Advocates of sociological institutionalism argue that many of these institutional forms and procedures are better understood as culturally specific practices. They are deeply influenced by the myths and ceremonies that form societal identity constructs. This stands in clear contrast to a formal means-ends efficiency calculation. Rather sociological institutionalists associate institutions with the transmission of cultural practices more generally. It is important to note that culture can be operationalized both narrowly and broadly. Narrowly, culture can refer to the patterns of knowledge, beliefs, and behaviour in a company or government body. Sociological institutionalists may look at a specific case or look at cases in a comparative sense. For example, they could be interested in why Google changed its motto from ‘Don’t be evil’ to ‘Do the right thing’ and its impact on their corporate culture.

Figure 5-21: Net Neutrality Protest. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/ari/4889202012/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Steve Rhodes.

Or they may compare institutions such as those found in government departments like Natural Resources Canada or Environment and Climate Change Canada. How do the respective cultures within these two departments within the same government influence what they do and how they do it? More broadly, culture can refer to shared and stable societal patterns of knowledge, belief, and behaviours: for example, Canada versus that of the US. How do their respective social institutions influence how health care is defined? And how does this influence health care policymaking?

Whether taken more narrowly or broadly, the goal is to understand the relationship between institutions and preferences. For example, sociological institutionalists are interested in explaining the striking similarities in organizational form and practice that Education Ministries display throughout the world, regardless of differences in local conditions. They are also interested in unexpected differences in behaviour between Education Ministries that share similar local conditions or are part of similar government structures. They are interested in how and why firms often display similar behaviour across industrial sectors regardless of their product. They are also interested when actors in the same sector behave differently. In each example, sociological institutionalism looks at how culturally informed institutions influence behaviour.

Figure 5-22. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/globe-crowd-skyline-civilization-1010591/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of TBIT.

The keenest insight of sociological institutionalism argues members of an institution are expected to obey the norms, rules, and procedures that constitute it. They are expected to be the guardians of the institution’s principles and standards. These are the norms of appropriateness associated with each institution and generated through socialization. We follow and defend norms because we believe they are natural, right, expected, and legitimate. We abandon such institutions when they began to weaken or fail. Sociological institutionalists are therefore interested in where norms come from, why they are respected when they lose force, and how they change.

If you haven’t already, read the James Walsh article (also listed in the Required Readings section of this module):

- “How Power and Institutions Affect Development” by the World Economic Forum https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/03/how-power-and-institutions-affect-development/

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- According to the reading, why should we take into account both traditional sources of institutional power and sociological institutions (what they call schematizing role)?

- How do they posit that both traditional and sociological institutions have influenced black Americans’ social and economic marginalization?

- How do they use this argument to explain counter-intuitive perceptions regarding authorities in Sierra Leon and India?

- Apply the argument of the reading to a policy issue in Canada.

Case Study: LGBTQ Rights in Canada

Given our discussion on how institutional structures present themselves as both formal and informal sets of rules, norms, and procedures, it is instructive to look at a policy area where both are discernible. Therefore, to explore the role of institutions in public policy, we will look at the shifting public policies on LGBTQ rights in Canada.

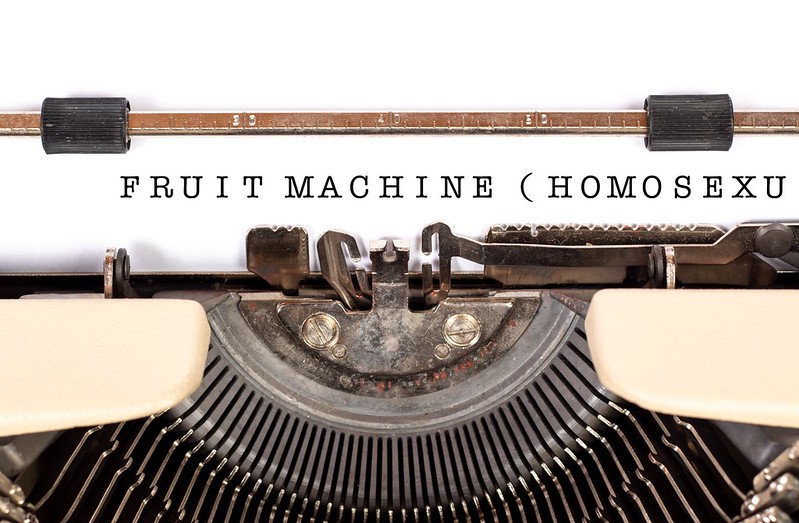

As a former colony, many of Canada’s earliest public policies were deeply influenced by British institutional structures. Under British Colonial rule, homosexuality was illegal, and a conviction of sodomy could result in the death penalty until 1861, when the punishment was reduced to a sentence of ten years to life in prison. Despite this slight improvement, the period between 1890 and 1969 was marked by increasingly punitive and intentionally vague policies that privileged the authorities’ power. Until 1948, the practice of homosexuality was labelled with gross indecency. In 1948 the categories of ‘dangerous sexual offender’ and ‘criminal sexual psychopath’ were passed into law, allowing the indefinite detention of those convicted of ‘homosexual acts.’ The ‘dangerous sexual offender’ label was applied to any person, though mostly males, likely to commit a sexual offence. This meant that any non-celibate gay person became a criminal. In the 1950s and 60s, during the Cold War hysteria, there were active discriminatory policies enacted as the government sought to purge LGBTQ people with the ‘fruit machine,’ a ‘homosexuality detection system’ that sought to detect arousal as evidenced by pupil dilation when shown sexualized material. We now recognize this as a highly discriminatory, invasive, and ineffective policy. However, it was believed to be necessary because members of the LGBTQ communities were perceived to be unreliable and could be leveraged or blackmailed into betraying their country.

Figure 5-23: The Fruit Machine. Source: https://flic.kr/p/2gm3V5G Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Trending Topics 2019.

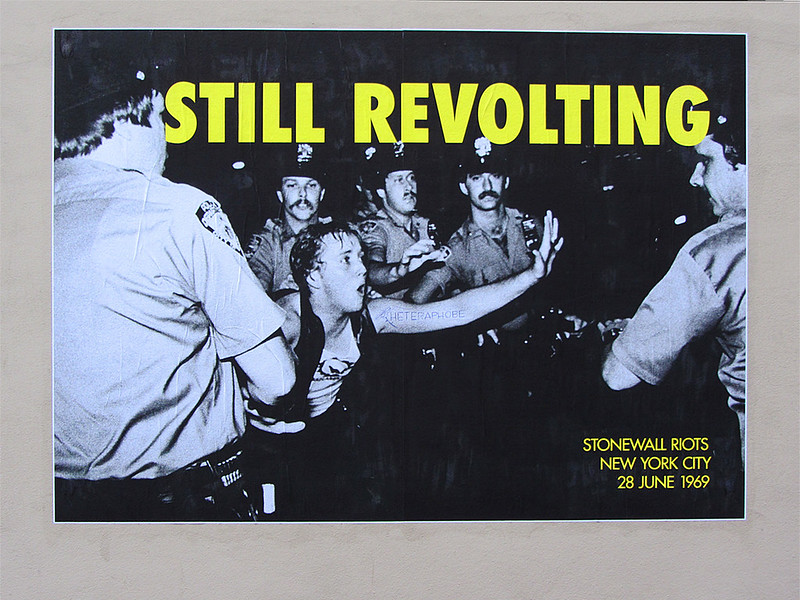

In the late 1960s, the policy trajectory regarding LGBTQ rights in Canada changed due to three events. First is the weeklong Stonewall Riots in New York City of 1969 by the LGBTQ community, sparked by the police raids on the Stonewall Inn. What emerged was the beginning of an organized movement of LGBTQ rights in the US. Second, in the UK, the British Parliament began to decriminalize homosexuality between consenting adults. These two events were highly influential in setting the global context for the debate on LGBTQ rights. In Canada, however, the discriminatory treatment of Mr. Everett Klippert was the primary catalyst of change. In 1960, Mr. Klippert was arrested and imprisoned for four years for gross indecency. In 1965, after his release, he was brought in for questioning in the North West Territories for an unrelated crime and charged with ‘gross indecency’ when he admitted to having had sex with four men. Mr. Klippert was subsequently designated a ‘dangerous sexual offender’ and sentenced to life imprisonment, a sentence upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada. However, in the context of changing social mores both globally and at home, the government of Pierre Elliot Trudeau passed Bill C-150 in 1969, decriminalizing gay sex. In light of this, Mr. Klippert was released in 1971.

Figure 5-24: The Stonewall Riots. Source: https://flic.kr/p/cm6VFb Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Newtown graffiti.

Figure 5-25: Michael Hendricks and René Leboeuf, the first same-sex couple to legally marry in Quebec. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hendricks-leboeuf2.jpg#/media/File:Hendricks-leboeuf2.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Montrealais.

Important historical milestones since then include the following:

- In 1972, Toronto held its first Pride celebration.

- In 1977, Québec’s Human Rights Code was amended to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.

- In 1981, the Toronto Police Service raided four bathhouses, arresting 300 men and provoking protests that were reminiscent of Stonewall in 1969.

- In 1982, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms enshrined the right to non-discrimination, but it would take until a 1995 Supreme Court of Canada decision for this to be extended to sexual orientation. In 1996, the Canadian Human Rights Act reinforced this Supreme Court decision as did legislation in most provinces.

Since the 1990s, there has been a string of progressive LGBTQ policies:

- In 1992, the ban on military service was lifted.

- In 1994, the ban on LGBTQ refugees was lifted.

- In 1995, the ban on same-sex couples adopting children was lifted.

- In 1999, same-sex common-law relationships were recognized.

- In 2005, same-sex marriages were recognized by the federal government.

- Until 2013, gay men were unable to donate blood, a practice stemming from the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Even now, however, gay men must have abstained from sex for three months to donate blood.

The Institutional Approach to Comparative Public Policy and LGBTQ Rights in Canada

How does an institutional approach to public policy analysis make sense of LGBTQ rights in Canada?

From the perspective of historical institutionalism, there is explanatory power in terms of historical contingency, path dependency, and critical junctures. In terms of historical contingency, LGBTQ policy in Canada was initially rooted in British law and tradition, where homosexuality was illegal and sodomy grounds for a death sentence. In terms of path dependency, we can see how early policy inherited from the British evolved in Canada from an act of ‘gross indecency’ to that of ‘dangerous sexual offender’ and ‘criminal sexual psychopath.’ In the 1960s, events in the UK, US, and, most specifically, the Everett Klippert case formed a critical juncture where LGBTQ policies changed the trajectory. From this point, a new path dependence formed towards the political, legal, and social acceptance of LGBTQ rights. An analysis using historical institutionalism would ask questions of how Canadian policymakers understood British traditions at the time of confederation. They would ask questions of how and why these early policies evolved in the direction they did. They would look to how developments in the UK, specifically the decriminalization of consensual homosexuality, and developments in the US, specifically the Stonewall Riots, challenged existing social, political, and ultimately legal norms, rules, and procedures. They would ask questions as to how these changes set LGBTQ policy on a new trajectory of path dependence.

From the perspective of rational choice institutionalism, LGBTQ policy can be explained by the actors’ interests. They would look to how the Canadian government’s interests were defined in the context of Canadian values, in the context of the Cold War, and later in the context of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. They would look at how those advocating for LGBTQ rights defined their interests within the legal, political, and social institutions.

From the perspective of sociological institutionalism, LGBTQ policy has been driven by normative structures. Therefore, questions would be asked of what norms are operative, how they have changed, why they have changed, and who has led the movement to change them. They would ask questions about what actions are appropriate in given contexts. For example, why were discriminatory norms, rules, and procedures deemed appropriate? How were these norms changed in the 1960s? What were the new norms, rules, and procedures that emerged? What is the appropriate behaviour given these new institutions that have emerged since the 1990s?

Finally, there is the comparative element. From a comparative public policy approach, we can ask how different institutional settings have resulted in different LGBTQ policies; for example, by comparing Canada to the US, the UK or other states where such a comparison may yield insight. We can ask questions about how norms have changed in Canada compared to other countries or how changes in other countries have influenced norms in Canada.

Figure 5-4: Canadian LGBTQ flag. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canada_Pride_flag.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Keepscases. |

Figure 5-26: American LGBTQ flag. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:USA_Lesbian_Gay_Bisexual_Transgender_flag.svg Permission: Public Domain. |

Figure 5-27: British LGBTQ flag. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:United_Kingdom_Gay_flag.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Edd. |

Watch the TED Talk “This Is What LGBT Life Is Like Around the World” https://youtu.be/ivfJJh9y1UI

If you haven’t already, read the Rosamond Hutt article (also listed in the Required Readings section of this module):

- ‘This is the state of LGBTI rights around the world in 2018’ by the World Economic Forum https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/06/lgbti-rights-around-the-world-in-2018/

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How do LGBTQ policies differ around the world?

- How can an institutional approach to the public policy make sense of LGBTQ policy?

- Using historical institutionalism, identify the role of historical contingency, critical junctures, and path dependency in LGBTQ policy at the global level.

- Using rational choice institutionalism, identify the role of interests in LGBTQ policy at the global level.

- Using sociological institutionalism, identify the role of norms in setting standards of appropriate behaviour in LGBTQ policy at the global level.

Conclusion

It is important to start the conclusion of this module by recognizing a crucial point made in Modules 3 and 4: in many ways, ideas, interests, and institutions are mutually constitutive. Take, for example, the three case studies introduced in Module 3, 4, and 5:

In Module 3, we examined the case of Canadian Middle Power internationalism. It was argued that ideational factors deeply influenced the shift in Canadian foreign policy post World War Two: by cognitive paradigms that shaped how Canada saw the world and its place in it; by shifts in a world culture that began to privilege the idea of global governance; by normative expectations of the internationalist role that Canada had internalized. However, this shift in Canadian foreign policy is partly explained by interests: Canadian policymakers saw it as the best way to achieve their security, prosperity, and agency goals. It is also partly explained by institutions. In the context of historical institutionalism, World War Two was a critical juncture that established a new path dependency. Rational choice institutionalism suggests the new institutions of global governance shaped how Canadian decision makers tried to achieve their preferences. And sociological institutionalism suggests that Canadian Middle Power internationalism is appropriate given the norms, rules, and procedures of the institutions of global governance.

The case study in Module 4 on Canadian environmental interest groups has a similar mutually constitutive logic. These groups had to decide how best to deal with the new Government of Justin Trudeau in 2015. Should they seek to be insider-groups with the ear of the government, even if this would compromise their independence or should they remain an outsider-group, keeping their independence intact but at the cost of influence? Interests are clearly at play here, but to a lesser degree, so are ideas and institutions. Ideational factors like cognitive paradigms and normative expectations would weigh heavy on such a decision. Institutional factors would also be at play. From the perspective of historical institutionalism, the election itself may be a critical juncture, which might shift these interest groups’ policy path. From the perspective of rational choice institutionalism, the government structure and the formal/informal policy processes structure how interest groups seek their preferences. Sociological institutionalism would examine the perception of the appropriate behaviour of environmental groups in their dealings with the government.

The case study in this module looked at LGBTQ public policy. From the perspective of historical institutionalism, the LGBTQ policy was deeply influenced by the historical contingency of British colonial rule. It was argued that between 1867 and 1969, as well as from 1969 onwards, there was path dependency on LGBTQ public policy. Rational choice institutionalism would look at how both the government and LGBTQ advocacy groups sought to achieve their preferences both before and after 1969, given the institutional constraints. Sociological institutionalism asks questions of what actions are appropriate for whom in given contexts. However, it is also very clear that ideational factors play a crucial role in LGBTQ public policy: framing, setting cognitive paradigms, and acting on dominant normative expectations. Interests are also clearly at play, especially advocacy groups’ role in fighting for non-discriminatory social policy. The point is that while ideas, interests, and institutions do provide insight into particular aspects of public policy, all three are mutually constitutive.

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the concept of the role that ‘institutions’ play in the public policy process. Despite the mutually constitutive relationship between ideas, interests, and institutions, it is still useful to look for cases where institutions have played an interesting role in the public policy process. We discussed how institutions function, both formally and informally. Formally, institutions act like a building that guide what we do. Informally, institutions guide how we do it. To be more precise, we defined institutions as both formal and informal rules. We see institutions in regular patterns of behaviour and in the rules and norms that influence and structure political behaviour.

Next, we looked to the dominant institutional approaches to public policy, including historical institutionalism, rational choice institutionalism, and sociological institutionalism. From this, we noted the importance placed by historical institutionalism on understanding historical contingency, path dependency, and critical junctures. From rational choice institutionalism, we noted the importance of exploring the relationship between structure and preferences. From sociological institutionalism, we noted the importance of understanding how norms shape what is deemed appropriate behaviour of actors in given roles and how these reflect institutional norms, values, and processes.

Finally, we closed with a case study that looked at institutional aspects of LGBTQ public policy. With this module, we finish looking at the mutually constitutive triad of ideas, interests, and institutions.

In the next module, we will be turning to politics’ role in shaping comparative public policy.

Review Questions and Answers

A building represents structural conditions that constrain or enable behaviour both formally and informally. Formally, a building has floors, stairs, hallways, doors, and rooms. This influences the most efficient means to navigate the building to a classroom, for example. Institutions play a similar role in public policy that the building plays in navigating the pathway to our classroom: they enable or constrain how we act. But how we navigate that space, is often deeply influenced by less formalized institutional structures. Whether we hold the door open for others, whether we walk on the right side of the ramp or the hallway, where we sit in the class, these are all influenced by socially driven norms: perceived standards of acceptable practice that are often derived through group interaction over time. There are also informal institutional structures in the public policymaking process. Every collective of people, from a friend group to a country, have socially derived norms. These norms are deeply influential at a conscious and subconscious level. They enable or constrain behaviour by shaping standards of appropriate behaviour.

In historical institutionalism, institutions are treated as formal rules, compliance procedures, and standard operating procedures that structure conflict or shape behaviour and outcomes. The core premise of historical institutionalism is that decisions that are taken at the formation of an institution shape its future trajectory and shape the policy outputs associated with the institution. The three key concepts at the core of historical institutionalism are a historical contingency, path dependency, and critical junctures:

- Historical contingency refers to the idea that past events and decisions contribute to the formation of institutions that influence current practices.

- Path dependency suggests that institutions, once constituted, exert pressure towards continuity and against change. This is because a lot of effort and resources go into creating an institution. Further, once operational, institutions require more time and more resources. In reaction, individuals and groups subsequently organize themselves around the form and function of these institutions. This makes the prospect of fundamental change risky for decision-makers: they will be opposed by those who benefit from an existing institution; they will be held responsible for the consequences of institutional change; they will potentially need significant resources to draft, pass, and implement new institutional structures; the consequences of policy change are unknown.

- Critical junctures are moments when uncertainty or indeterminacy opens a window for agency and therefore potentially for institutional change. Essentially, critical junctures are moments when changing the trajectory of a policy path is possible.

Together, these three factors provide the explanatory power of historical institutionalism.

Rational choice institutionalism posits actors as bounded by institutional norms, rules, and procedures within which they compete with other egoistic actors to achieve their preferences. From this perspective, institutions may solve collective action problems when there is a difference between individual rationality and group rationality. For example, while there collectively may be a benefit in preserving a common resource, individually, there may be a benefit in overutilization. Institutions may address such collective action problems by providing a forum where actors interact with each other, cooperate with each other, and find solutions to common problems. Institutions also reduce ‘transaction costs’ which are part of collective action problems. In economics, institutions represent a set of formal and enforced rules governing relationships between individuals or organizations. The aims are to maintain the trust required for them to reach agreements and reduce the likelihood that agreements between actors are broken. This reduces uncertainty and decreases the costs associated with wasted effort on joint tasks that are not fulfilled. However, it is important to note from a rational choice institutionalist perspective, that once these institutions are constituted, they frame how an actor seeks to achieve their preferences.

Sociological institutionalism suggests that institutions are less a function of efficiency concerns and more a function of culture and a logic of appropriateness. From this perspective, institutions represent a relatively stable set of norms, rules, and procedures that are rooted in the contextual practices of the specific groups of people. Once constituted, these culturally informed institutions shape how actors interpret the world and inform appropriate ways to act within it. One way that institutions shape interpretations and inform behaviour is through defining the appropriate ‘role’ of actors within particular contexts. Therefore, institutions not only constrain and enable what actors can do, but they also deeply influence perceptions and preferences of what actors should do. This in turn, if deeply internalized, influences what actors believe to be appropriate, good, and right. This suggests an important insight of sociological institutionalism: institutions once constituted are more than the preferences of the actors who created them. From a sociological approach, institutions can solidify over time and will resist change. This is important in that it fosters stability, durability, and continuity.

Glossary

Bill C-150: a bill passed in 1969 by Pierre Trudeau’s government decriminalizing homosexuality.

Collective action problems: a situation where the uncoordinated action of individuals is less beneficial or efficient than coordinated action.

Critical juncture: moments of policy uncertainty that create opportunities for significant change to occur.

Dangerous sexual offender: a label created in 1948 and applied to any person, though mostly males, likely to commit a sexual offence. This label was used to convict people for homosexuality.

European integration: the process of post-war European states cooperating to build institutions that would allow them to leverage their combined economic, political, and security resources.

Formal structures: the legal or procedural rules which establish how public policy is drafted, passed, and implemented.

Group rationality: reason or logic of a group that takes the welfare of the whole as the reference point.

Historical contingency: the idea that past events and decisions contribute to the formation of institutions that influence current practices.

Historical institutionalism: the decisions made during the shaping of an institution shape the future of the institution and its policies.

Individual rationality: reason or logic of an individual that takes the welfare of the individual as the reference point.

Informal structures: those rules or patterns of behaviour that are observable but uncodified.

Institutions: both formal organizations and the informal patterns of rules, norms, and practices that shape the behaviour of actors.

The logic of appropriateness: making decisions based on contextual expectations of the role, held both by the actor and those around the actor.

Mr. Everett Klippert: arrested and criminally charged for being gay in the 1960s, released following the passing of Bill C-150.

Norms: a standard of behaviour that is expected in a group and is usually socially derived.

Path dependency: suggests that once created, institutions prefer to continue on their initial path while resisting change.

Preferences: the order of choice an actor gives to alternatives relative to their context.

Rational choice institutionalism: argues that institutions set structural boundaries within which decision making happens.

Sociological institutionalism: argues that institutions are deeply influenced by cultural context.

Stonewall Riots: 1969 riots in New York City by the LGBTQ community, sparked by police raids on the Stonewall Inn.

Transaction costs: the costs incurred by undertaking an economic exchange.

References

Barton, Rosemary. "Justin Trudeau Vows To End 1St-Past-The-Post Voting In Platform Speech". CBC News, 2015. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/justin-trudeau-vows-to-end-1st-past-the-post-voting-in-platform-speech-1.3114902.https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/justin-trudeau-vows-to-end-1st-past-the-post-voting-in-platform-speech-1.3114902

Capoccia, Giovanni. “Critical Junctures and Institutional Change.” Chapter. In Advances in Comparative-Historical Analysis, edited by James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen, 147–79. Strategies for Social Inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Chan, Stephen. "What Is The Future Of Foreign Aid?". The Guardian, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2016/oct/27/what-is-the-future-of-foreign-aid.https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2016/oct/27/what-is-the-future-of-foreign-aid

Clément, Dominique, and Association of Canadian University Presses Issuing Body. Human Rights in Canada: A History. Laurier Studies in Political Philosophy Series. 2016.

"Dangerous Offender Designation". Public Safety Canada, 2015. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/cntrng-crm/crrctns/protctn-gnst-hgh-rsk-ffndrs/dngrs-ffndr-dsgntn-en.aspx?wbdisable=true.https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/cntrng-crm/crrctns/protctn-gnst-hgh-rsk-ffndrs/dngrs-ffndr-dsgntn-en.aspx?wbdisable=true

Fabbrini, Sergio. "The American System of Separated Government: An Historical-Institutional Interpretation." International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale De Science Politique 20, no. 1 (1999): 95-116.

Kohut, Tania. "What Trudeau Said: A Look Back At Liberal Promises On Electoral Reform". Global News, 2016. https://globalnews.ca/news/3102270/justin-trudeau-liberals-electoral-reform-changing-promises/.https://globalnews.ca/news/3102270/justin-trudeau-liberals-electoral-reform-changing-promises/

Larionova, Marina, and Kirton, John J., Editor. BRICS and Global Governance. Global Governance (Series) (Ashgate (Firm)). 2018.

Levi, M. (1997), ‘A Model, a Method and a Map: Rational Choice in Comparative and Historical Analysis’, in Lichbach, M. I. and Zuckerman, A. S. (eds.), Comparative Politics: Rationality, Culture, and Structure, New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 19–41

"LGBTQ Rights and the Citizenship Regime in the Neoliberal Age." In Citizenship as a Regime: Canadian and International Perspectives, 97. Montreal, Kingston; London; Chicago: MQUP, 2018.

Mixner, David. "WHAT STONEWALL MEANS." Variety 344, no. 14 (2019): 94-95.

North, Douglass Cecil. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990.

Ostrom, Elinor. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Pritchard, Trevor. "How The Cold War 'Fruit Machine' Tried To Determine Gay From Straight". CBC News, 2016. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/archives-homosexuality-dector-fruit-machine-1.3833724.https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/archives-homosexuality-dector-fruit-machine-1.3833724

Rau, Krishna. "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual And Transgender Rights In Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2014. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-rights-in-canada.https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-rights-in-canada

Riggs, Fred W. "Presidentialism versus Parliamentarism: Implications for Representativeness and Legitimacy." International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale De Science Politique 18, no. 3 (1997): 253-78.

Smithson, Nathaniel. "Google’S Organizational Culture & Its Characteristics (An Analysis)". Panmore Institute, 2018. http://panmore.com/google-organizational-culture-characteristics-analysis.http://panmore.com/google-organizational-culture-characteristics-analysis

"TIMELINE | Same-Sex Rights In Canada". CBC News, 2012. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/timeline-same-sex-rights-in-canada-1.1147516.https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/timeline-same-sex-rights-in-canada-1.1147516

Supplementary Resources

- Claudio M Radaelli, Bruno Dente, and Samuele Dossi. "Recasting Institutionalism: Institutional Analysis and Public Policy." European Political Science11, no. 4 (2012): 537-550.

- Turner, David. "COMPLEXITY, INSTITUTIONS AND PUBLIC POLICY: AGILE DECISION‐MAKING IN A TURBULENT WORLD ‐ Edited by Graham Room." Public Administration90, no. 1 (2012): 288-90.

- Reich, Simon. "The Four Faces of Institutionalism: Public Policy and a Pluralistic Perspective." Governance 13, no. 4 (2000): 501-22.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. “Institutions in Comparative Policy Research,” Comparative Political Studies 33, 6-7 (September 2000): 762-90.