Overview

Figure 6-1: A linear, rational process. Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/cycle-recycling-recycle-arrows-150947/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of OpenClipart-Vectors.

So far, in Modules 1-5, we have introduced a variety of frameworks to conceptualize and operationalize comparative public policy. In Module 1, we looked at the policy cycle and why public policy matters. In Module 2, we looked at the logic of comparative politics and some of the dominant approaches to explaining differences, including the cultural, economic, political, institutional, and critical approaches. In Module 3-5, we introduced the utility of looking at policy issues through the lenses of ideas, interests, and institutions, as individual approaches while recognizing these three variables are, in many ways, mutually constitutive.

However, the approach taken so far is, in many ways, a bit misleading. For example, it may seem that public policy is a relatively linear process: problems are identified and put on the agenda by decision-makers, bureaucracies and epistemic communities suggest solutions, decision-makers debate the options, identify the best solution, and implement it. This linear conception is very clean and precise. It is very rational. It meets most people’s standards of the ‘right way’ to solve policy issues.

In practice, public policy is rarely so neat. Rather, it is often the case that policy issues, policy solutions, and the political context are operating independently of one another or even at cross purposes. A new policy may start as a ‘pre-packaged’ solution looking for a problem to solve. It may start as a shift in the political context, where decision-makers are looking to make their mark on the policy agenda. It may start as a sudden threat or opportunity that decision-makers face, but one in which the lack of feasible options stymies a 'solution.' Each of these examples runs counter to the neat image we often have of the linear policy process. Instead, it suggests that public policy is a complex process.

Figure 6-2: A complex process. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/question-mark-labyrinth-lost-maze-2648236/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of AbsolutVision.

Moreover, it may seem that all policy issues are simply waiting for ‘their turn.’ That policy-makers will eventually address all policy issues. They will do so rationally, finding the optimal solution and without bias. However, this is one of the biggest misconceptions of public policy. While deeply significant to some people, many policy issues have difficulty making it onto the institutional agenda of decision-makers. Such issues may linger in narrow segments of the systemic agenda for an indeterminant period, and ‘their time’ may never arrive regardless of how important they may be for specific sub-sections of the polity. Policymakers have to balance a wide variety of demands made by their constituents, the civil servants acting on their behalf, their political party, and even their preconceived ideas of what is appropriate. In the end, policymakers have to decide where to spend the resources at their disposal by choosing how much, if anything, to commit to these demands.

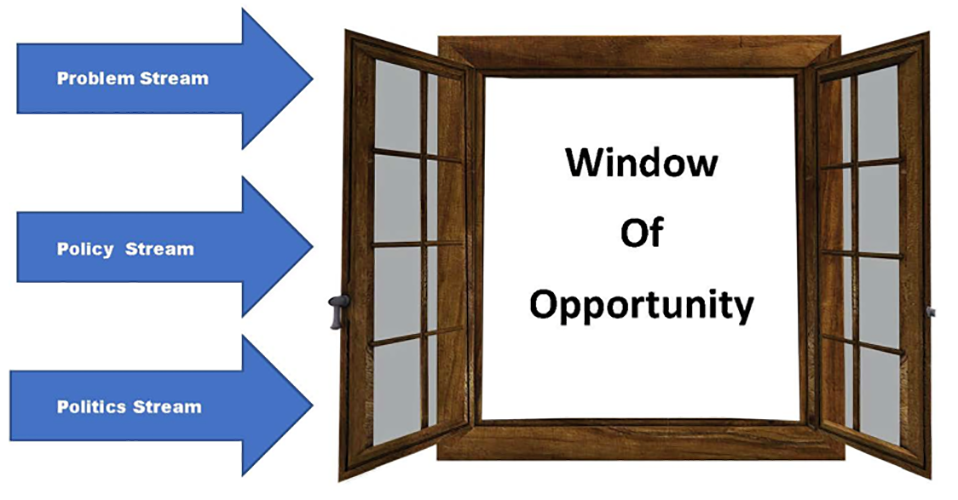

Both policy complexity and the selection of policy issues point to an important factor that we have alluded to but are not directly engaged with: politics. Therefore, in this module, we will turn to the concept and role of politics in the public policy process. Specifically, we will introduce the multiple stream approach (MSA) to public policy. More specifically, we will introduce the concept of a ‘policy window’ as defining that moment when an issue, a solution, and political will align to address a policy issue.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define the concept of ‘politics’ in public policy.

- Disaggregate aspects of public policy decision making into the problem, policy, and politics streams of the multiple streams approach (MSA).

- Critically analyze the concept of a ‘policy window’.

- Assess the comparative potential of policy through the multiple streams approach.

- Politics

- Civic disconnect

- Authoritative allocation

- Scarce resources

- Political community

- ‘Rational’ policy response

- Multiple stream approach (MSA)

- Problem stream

- Wicked problem

- Attention

- Sustained attention

- Focusing event

- Policy stream (or solution stream)

- Deregulation

- Devolution

- Epistemic community

- Off-the-shelf policy solution

- Feasibility

- Policy entrepreneur

- Politics stream

- National mood

- Policy window

- Consequential coupling

- Doctrinal coupling

- Policy universality

- Problem stream

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

Cairney, Paul, and Nikolaos Zahariadis. “Multiple streams approach: A flexible metaphor presents an opportunity to operationalize agenda-setting processes.” Handbook of public policy agenda setting (2016): 87-105. Available at https://paulcairney.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/cairney-zahariadis-multiple-streams-2016.pdf. [Online link]

Tenove, Chris. “The Meme-Ification Of Politics: Politicians & Their ‘Lit’ Memes”. The Conversation, 2019. Available at https://theconversation.com/the-meme-ification-of-politics-politicians-and-their-lit-memes-110017. [Online link; for Learning Activity 6-2]

Hallsworth, Michael, and Mark Egan. “What Should Government Pay Attention To?”. The Behavioral Insights Team, 2018. Available at https://www.bi.team/blogs/what-should-government-pay-attention-to/. [Online link; for Learning Activity 6-3]

Learning Material

Introduction

Figure 6-3: Political promises. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/silhouette-balloon-promise-774835/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

In this module, we will be bringing together many of the threads that have been introduced so far through the concept of politics. However, it is important to note right from the start that just the word ‘politics’ is contentious these days. There is a growing sense that politics has become synonymous with under-handed tactics, top-down bullying, elitist debates, money, and corruption. It has become ‘something’ done by ‘those people over there’. Many seem to think that what ‘those people’ are doing has nothing to do with ‘us’ or, if it does, there is nothing ‘we’ can do about it. To support this thesis, we can look to the steady decline in voter turnout across established democratic countries and the steady decline in political party participation.

However, this is a highly problematic proposition as summed up nicely by a quote attributed to Mahatma Gandhi: “anyone who says they are not interested in politics is like a drowning man who insists he is not interested in water.” Politics play a determinative role in almost everything we do: from the domestic and international institutions that shape our behaviour, through to the tuition we pay at university, to who does what in our homes. Likewise, politics is determinative in public policymaking. It shapes both systemic and institutional agendas, the process of policy formulation, the criteria for policy adoption, the means of implementation, and even the form of evaluation. Parties’ political platforms during elections are potential points of divergence in policy paths. Politics shape, and are in turn shaped by, cultural ideas of what is appropriate of particular actors, in particular places, in particular times. Politics is the modus operandi of interest group advocacy. The institutions of public policy, both formal and informal, are an exercise in politics. Moreover, how politics operates in all of these aspects of public policymaking differs between place and time – opening the door to interesting comparative questions.

In order to operationalize the concept of politics in this module, we are going to use the multiple streams approach (MSA), first introduced by Jon Kingdon (1995). The MSA suggests that public policymaking is non-linear and constituted by distinct and possibly divergent streams: the problem stream, the policy stream (or solution stream), and the politics stream. According to Kingdon, all three of these streams must come together for a ‘policy window’ to open and allow for the potential of policymaking.

Figure 6-4: The Multiple Streams Approach (MSA) and the Policy Window. Permission: Courtesy of course author Martin Gaal, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan, based on https://pixabay.com/illustrations/window-open-window-glass-outlook-1798492/

The first two of these streams, the problem stream and the policy/solution stream, are necessary conditions for policymaking. However, as we will argue in this module, the third political stream is determinative – there must be political will for policymaking on specific issues.

The module will begin with a definition of politics, which is highly contested like many of the concepts we have dealt with in this course.

The next section introduces the multiple streams approach, looking at the problem stream, policy stream, politics stream, and the concept of a policy window. We will also look at how the MSA opens public policy to comparative questions.

Before moving on, let us assess how you feel about politics. Think about one word which you believe is the best synonym for politics. Write this down on the following Padlet board. On this board, you can also “upvote” / “downvote” posts that you agree or disagree with.

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include:

- Your Padlet contribution

- The Padlet contribution by one of your classmates and why you think this is a strong contribution

What is Politics?

Figure 6-5: The ballot box. Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/ballot-box-box-poll-election-vote-32384/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Clker-Free-Vector-Images.

What is politics? Why should we look at politics when discussing public policy? Like many of the concepts introduced in this course, defining politics is not simple. The broadest definition of politics would encompass almost all human interaction, putting into question the concept’s utility. The narrowest definition would restrict the concept of politics to the formal practice of governing, omitting much that shapes many aspects of public policy, including those informal institutions we spoke of in the last module. Making an operational definition even more problematic is the increasingly negative view of politics held by the general public. Many people associate ‘politics’ with power-hungry individuals, seeking to satisfy their self-interested preferences. People see the power of ‘money’ to buy influence through campaign contributions or lobbyists. They see politics as something disconnected from themselves, as a contest between powerful actors fighting amongst themselves with little regard to the lived experiences of those they purportedly represent. Many believe that their ability to influence politics is limited to voting every four years.

This trend towards a civic disconnect is problematic for a healthy democracy, and it is problematic for our focus on public policy. If public policy matters, as asserted in Module 1, then it is crucial that people are engaged in the process. We argued that public policy plays a determinative role in issues that affect our quality of life. These issues include a vast array of topics: food safety, a clean environment, affordable housing, accessible healthcare, quality education, tax rates, tuition costs… the list goes on. These are all issues that deeply impact citizens’ lives. If public policy matters, if politics deeply impacts public policy, and if people see politics pejoratively, then people may be alienated from the process of public policymaking. Therefore, it is very important to define politics and assess its role in public policymaking.

Figure 6-6: Civic disconnect. Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/KVOtJAxULK4 Permission: Public Domain. Photo by Pawel Czerwiński on Unsplash

The working definition of politics in this course builds on the work of David Easton (1953): politics is the authoritative allocation of scarce resources in a given political community. It is useful to break this definition down into its constituent elements:

- The idea of ‘authoritative allocation’ means someone individually or collectively has the right to decide who is going to get what.

- The idea of resources refers to inputs, including money, time, labour, and natural resources. It is important to note that these are ‘scarce’ resources, meaning they are finite in quantity, requiring tough decisions on where to allocate them.

- Finally, the idea of a ‘given political community’ bounds the decision making to a select group, such as the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, or Canada.

There are some notable implications of this definition. First, if resources are scarce, that means there is competition for these resources. Second, if there is a competition for resources in a society, there must be a means to adjudicate their distribution. Finally, for decisions about distribution to be accepted, they must be seen as legitimate. Collectively, this is the realm of politics.

Figure 6-7: The University of Saskatchewan. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/curacumba/7491545734/in/photolist-cq18xC-nb4UdF-nsxTMB-hb1Mtk-rJQiFQ-rM1Dfd-FKcbcC-cRq3Af-rM1CAs-ruEUfB-qQkqat-ruEVWH-cRqhE7-ruETMx-rM8caM-eiXGXS-cRq8yQ-ruxmqs-rJQjow-qQkpJP-rM31dx-rsNwAP-ruyxzm-rsNxBX-ruEVhg-nsgQhu-nb4yXQ-nsxSt4-nsxR52-nb4rSV-nsAtB5-nqvx87-nb4BR5-nb4wec-nb4BPQ-nqvsXy-nb4Bob-2gStQQ3-2gStYQ1-rsNwSa-ruyycy-rM8cna-qQks3X-ruyyso-ruxo8A-rM1G3Y-rM33qZ-rM1Gzj-rM1FB7-FKceGo Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Kyla Duhamel.

Harold Lasswell (1958) sums this up in a more pithy way to define politics: who gets what, when, and how. It is interesting to note how much this definition overlays our working definition of public policy: whatever the government chooses to do or not to do. For example, in Canada, the federal and provincial governments have the authority to decide who is going to get what based on the constitution and the legitimacy conferred by democratic elections. The government must decide which public policies they are going to commit to providing some of their finite resources. And, by necessity, which public policies they are not going to commit to providing some of their finite resources. For example, should the government invest heavily in environmental policies in pursuit of meeting its international commitments, like those agreed to in the 2015 Paris Agreement, and in mitigating the ‘climate emergency’? Or should the government invest heavily in developing its natural resources in pursuit of economic growth? Or should the government try to balance its pursuit of environmental policy and economic policy? Is this even possible? It is not possible to answer these questions without bringing politics into the conversation.

Figure 6-8: Keystone XL Pipeline Protest at the White House, Washington, DC, November 6, 2011. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/tarsandsaction/6320926426/in/photolist-aCypd7-aCynSj-aCvEKK-aCvE1r-aCyoq7-aCyoib-aCymgo-dZ7o1z-hDUQ1i-WP14ZT-Uh43hx-aiseZP-aiv3cy-U5tXGP-aiv34J-aisf2n-aiv3eq-aiseU4-27QXoBJ-aiseQi-23j9CM8-Rty1u3-Zs9isH-RuN8tw-U5u1wX-dVnX4W-af4gty-DmgcFC-U5tYLn-aCypxU-aCvHPr-RKhtsu-RC69YV-RzoFam-Qwpk7w-RNThw2-26KhpeL-RKhtdm-aCMtoL-aCvHLD-RKhtaq-RC6a3x-aCynWS-RzoF75-aCyotU-aCyo1h-aCymH7-aCyo59-aCymCy-QwpjXU Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of tarsandsaction.

However, it is arguable that our application of the working definition of politics is too narrow since decisions about who gets what, when, and how are not restricted to Ottawa, Regina, Saskatoon, or the Board of Governors at the University of Saskatchewan. Rather, these decisions are made between couples, friend groups, families, churches, and other bounded communities. These private decisions are, therefore, also deeply political. For example, in many families, the allocation of chores to children is heavily gendered. It is more common for boys to mow the lawn and take out the garbage, while it is more common for girls to do the dishes and other household chores. Moreover, these decisions influence what individuals and communities believe to be right, proper, and good. These perceptions, in turn, influence what the government believes they should do, what decisions are right, and how they should allocate the resources at their disposal. This connection between the private and the public links the realm of personal politics to our more formal definition of public policy as what governments choose to do or not to do. Going further, we can extend the impact of politics if we include all the groups that are trying to influence both formal and informal decision-makers: the lobbyists, the interest groups, and the social movements, for example.

If we take all this together, it is clear that politics plays a fundamental role in public policymaking. However, as a simple function of this breadth, it can be difficult to operationalize politics in public policy analysis. One useful way to deal with this dilemma is to use the multiple streams approach (MSA) to public policy analysis and, more specifically, how the problem stream, policy stream, and politics stream all need to come together in a policy window for policy movement. The MSA is the subject of the next section in this module.

If you haven’t already, read the Chris Tenove article (also listed in the Required Readings section of this module):

- “The meme-ification of politics”, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/the-meme-ification-of-politics-politicians-and-their-lit-memes-110017

Next, use a meme-generator site, like the one found at https://imgflip.com/memegenerator, to make a meme that applies ‘politics’ to the public policy issue that you have chosen to focus on for your Podcast and Policy Brief assignments in this course.

Lastly, share your meme to the following Padlet board.

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include:

- Your Padlet contribution

- The Padlet contribution by one of your classmates and why you think this is a strong contribution

Multiple Stream Approach (MSA) to Public Policy Analysis

Figure 6-9: Limited time. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/deadline-stopwatch-clock-time-2636259/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of AbsolutVision.

Almost every day, we see policy announcements by various levels of government. The University of Saskatchewan may announce a new policy on tuition. The City of Saskatoon may announce a policy on backyard fire pits. The Saskatchewan Government may announce a policy on carbon pricing. The Canadian Government may announce a policy on environmental regulations. These policy initiatives have direct implications for how we live, work, and study. The debates over these policies, both while being drafted and after implementation, make public policymaking seem immediate and rational, albeit also contentious. It appears to the general public that someone raises an issue, professionals discuss solutions, policymakers choose the best option, and bureaucrats implement them. This rational process closely resembles the ideal ‘policy cycle’ we discussed earlier.

However, this is misleading. Policymakers may choose not to address many policy issues on the systemic agenda, leaving them in limbo for an indeterminate amount of time. Conversely, policy issues may unexpectedly make it to the institutional agenda due to a sudden change in circumstances. In this case, decision makers may not have the time or information necessary to fulfill the demands of a fully ‘rational’ policy response. In response, actors both within government and the wider policy community may pitch existing policy options to these ‘new’ problems to further their narrowly defined interests.

It is important to note a couple of things that emerge when we contrast the ideal type of a linear ‘rational’ policy process with the more chaotic and bounded type of policy process we often see in practice. First, public policy issues and solutions exist independently of each other. There are many problems on the systemic agenda that people are trying to elevate to the institutional agenda. At the same time, many policy solutions exist, looking for a problem to solve. This may seem counter-intuitive, but decision makers and interest groups will often have a preconceived idea of what a policy solution will look like – even if they do not know the specifics of a problem. If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail: if you are an ideological fiscal conservative or environmentalist, every policy problem will look like a fiscal or environmental problem. Therefore, when a ‘new’ policy issue makes it onto the institutional agenda, actors often look to those solutions that have worked in the past and/or are in their narrowly defined self-interest.

Figure 6-10: The institutional agenda. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/finance-accountancy-savings-tax-2837085/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of mohamed_hassan.

Second, politics plays a more significant role in practice than is suggested in the linear and rational policy cycle. If we characterize policymaking as rational, it suggests we are looking for the best or even technical solution to a policy problem. But if policymaking is less rational and more disaggregated than the policy ‘cycle’ suggests, there are more entry points for politics to play a role. The selection of which policies to elevate to the institutional agenda and commit resources to is the definition of politics: who gets what and when. The competition between self-interested groups to offer a policy solution is deeply political, as is the decisionmaking. To explore the political nature of public policymaking and suggest the means of comparative public policy analysis, we will introduce Kingdon’s multiple stream approach (MSA). Specifically, we will look at his argument that public policymaking requires an alignment of a problem, a solution, and political will. When these elements are all aligned, a window of opportunity opens for policymaking to happen.

Figure 6-11: Aligning a problem, a solution, and political will. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/idea-plan-action-success-concept-1855598/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

In the following sections of this module, we will examine the streams of the multiple stream approach:

- The problem stream;

- The policy stream; and

- The politics stream,

and the potentially following policy window.

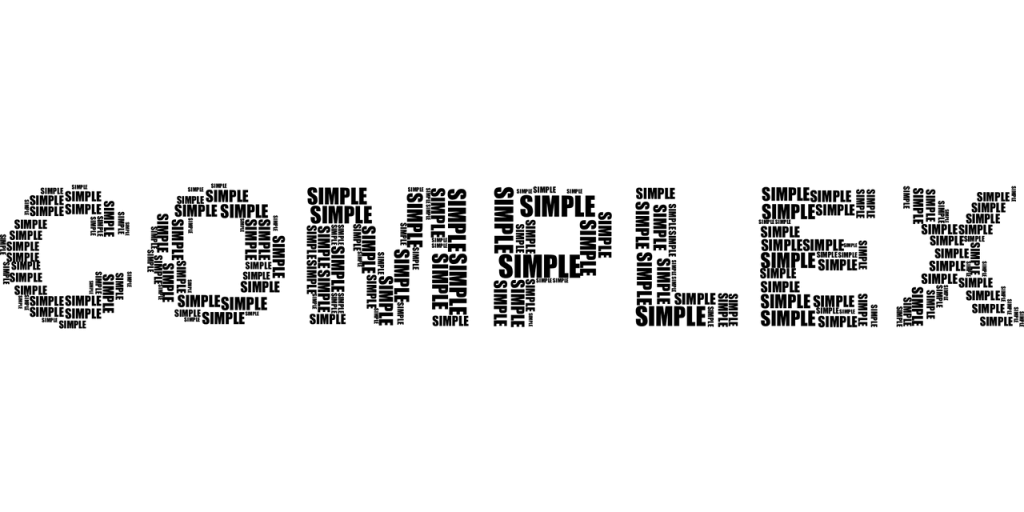

MSA stream 1: Problem Stream

If we were to take a brief survey of those policy issues on the systemic agenda, we would find a myriad of problems that individuals and groups believe the government ‘must’ address – these myriad problems constitute the problem stream. Some of these problems are common to almost all governments in all places. For example, the government must grow the economy and facilitate citizen’s prosperity. At the same time, the government must also protect the environment and save future generations from the worst impacts of climate change. As another example, many argue the government must provide robust social services to invest in a country’s human capital and provide a minimum standard of living for its citizens. At the same time, others argue the government must balance the budget and not mortgage the prosperity of future generations. Balancing such dichotomous expectations is what Rittel and Webber (1973) call a ‘wicked problem.’ These are complex problems with no easily defined solutions, unlike physics or math, and rarely have a clear policy path forward.

Figure 6-12: A wicked problem. Source: https://pixabay.com/vectors/simplex-simple-complex-abstract-2730769/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of GDJ. Web

On top of these more generic problems, the government must address those unexpected or externally driven problems which arise. For example, western Canadian provinces have had to address the problem of increasingly frequent, extreme, and costly forest fires. In 2019, the Canadian and Saskatchewan governments had to deal with the Chinese Government’s decision to ban Canadian canola, pork, and beef in retaliation for the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou. Governments from around the world took drastic measures in responding to the events of September 11th, 2001, when Al Qaeda hijacked airplanes to take down the Twin Towers in New York City.

Figure 6-13: Ground Zero, New York City, N.Y. (Sept. 16, 2001). Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/slagheap/243447330/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of slagheap.

Finally, on top of the more perennial policy problems and the externally driven policy problems, decisionmakers are faced with various demands from lobbyists, interest groups, and broader social movements. In Canada, these could include First Nations treaty claims, provincial equalization payment reform, or universal pharmacare. In the US, these could include gun control, health care reform, or lowering the tax burden. In the European Union, these could be the issue of supranational authority, EU competencies, or social policies. All of these policy issues compete for the attention of the government and decisionmakers.

Figure 6-14: March For Our Lives, a student led rally for gun control in the US. New York City, 2018. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/wasik/40992598351/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of mathiaswasik.

Given the range of policy demands, it is simply not possible for policymakers to devote the attention necessary to address all of these problems. Some problems will remain on the systemic agenda indefinitely. Others will make it to the institutional agenda but fail to progress any further. Still, other policy issues will remain unsolved even with a legitimate effort by the state to address them. Realistically, policymakers can only attend to a select number of policy problems due to limited resources and time. The question then becomes, why these problems and not those problems? Are the demands for clean drinking water by northern communities and, in particular, First Nations Reserves not as important as the demands made by provinces and private companies for pipelines? If they are as important, then why did the government spent 4.5 billion on one pipeline in 2019 when there are 56 long term boil water advisories in effect across Canada? Moreover, the issue of clean drinking water has been a protracted policy problem. The Neskantaga First Nation has had a boil water advisory in effect for 25 years. The Liberal Government of Justin Trudeau has devoted more resources to addressing the problem of clean drinking water on Reserves and promised to eradicate the problem by 2021. But the problem has been on the institutional agenda for nearly half a century. In 1977, then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau promised to provide water and sanitation services that would be on par with non-Aboriginal communities. Nearly 50 years later and many on Reserve are still waiting.

Figure 6-15: Drinking water. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/coaxial/2088705074/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of JoshNV.

Figure 6-16: Confrontation can lead to attention. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/conversation-talk-talking-people-799448/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of kabaldesch0.

A useful way to gauge the likelihood of a policy problem making it to the institutional agenda is via the concept of ‘attention.’ Many policy problems may receive peripheral attention. An official of some sort might make a side comment on a particular problem, especially when confronted by those advocating on its behalf. However, attention in such cases can be fickle and will likely have evaporated by the time the official meets the next person on their schedule. It usually requires ‘sustained attention’ for meaningful progress on a policy problem.

For example, there has been an utter lack of sustained attention to the problem of clean drinking water on reserves. Rather, the problem has started and stopped fitfully in different jurisdictions by different governments, leading to a disjuncture in policy progress. Kingdon suggests that sustained attention is likely when a policy problem resonates with a policy solution already in the back of a decisionmaker’s mind. Then, when confronted by a policy problem, policymakers can draw upon their preconceived notions of what can be or should be done. For example, PM Stephen Harper had strong views on limiting the reach and scope of federal government action. Therefore when an issue of government regulation moved on to the institutional agenda, he and his cabinet were receptive to policies that limited the federal government’s power: from environmental impact assessments and resource extraction project approval to the financial sector, food safety, and telecoms.

Figure 6-17: Former prime minister Stephen Harper. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stephen_Harper_-_Davos_2010.jpg#/media/File:Stephen_Harper_-_Davos_2010.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Remy Steinegger.

Sustained attention may also coalesce via a ‘focusing event’: a critical moment that brings a policy issue front and centre in the public eye. For example, the 2008 financial crisis focused global attention on the US sub-prime mortgage crisis, the European debt crisis, the problems of ‘institutions being too large to fail’, and the risk brought by deep interdependence in the international economic system. The 2011 Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant disaster in Japan focused global attention on nuclear power safety. The 2013 Lac-Mégantic rail disaster focused the public’s attention on the dangers of transporting petroleum products via rail and the woefully inadequate regulation of rail transport. The 2016 Fort MacMurray fire focused the public’s attention on urban encroachment, climate change, and forestry management. These events splashed a policy issue across the news and were the focus of public discussion and concern. In response, the public demands policy responses to these immediate or potential threats.

Figure 6-18: 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Landscape_view_of_wildfire_near_Highway_63_in_south_Fort_McMurray_(cropped).jpg#/media/File:Landscape_view_of_wildfire_near_Highway_63_in_south_Fort_McMurray_(cropped).jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of DarrenRD.

These demands create new questions. Will the attention of policymakers be sustained? If it is, will it be sufficient to achieve meaningful progress on the policy problem? To begin to answer these questions, we need to look at the next component of MSA, the policy stream.

If you haven’t already, read the Michael Hallsworth and Mark Egan article (also listed in the Required Readings section of this module):

- “What Should Government Pay attention to?”, The Behavioral Insights Team, https://www.bi.team/blogs/what-should-government-pay-attention-to/

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- What is availability bias?

- How does availability influence public perception?

- How do decisionmakers use heuristics to decide their policy agenda?

- Why does this lead to policy over-reaction and under-reaction?

- Consider the public policy issue that you have chosen to focus on for your Podcast and Policy Brief assignments in this course. How can this discussion be applied to that issue?

MSA stream 2: Policy Stream

The policy stream (or the solution stream) is where policymakers look to find solutions to those policy problems that they deem worthy of their sustained attention. However, before examining the policy stream, there is one important caveat to mention. The policy stream is, in many ways, distinct from the problem stream. Again, this is counter-intuitive to the linear conception of an idealized public policy process whereby a problem is identified, and the most rational solution is found and then implemented. Instead, the MSA treats the policy stream as independent of the problem stream for two primary reasons.

Reason 1: Given limited time and resources, policymakers must find feasible solutions

Figure 6-16: Deregulation. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/143106192@N03/44194297812/ Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Mike Cohen.

First, as we detailed in the last section, achieving progress on policy problems requires the sustained attention of policymakers. We also noted that decisionmakers, by necessity, had to choose which problems to give their attention to, including perennial problems, problems on the systemic agenda, and those problems suddenly thrust into the news from an unexpected crisis. This often means there are insufficient time and resources to generate fully rational policy responses tailored to a specific problem. Rather, policymakers will first draw upon those policy responses or policy solutions at hand. Some of these will be rooted in their ideological predispositions.

For example, Prime Minister Harper believed the federal government should be limited. Therefore, when faced with an issue dealing with the government’s role in the economy or people’s social welfare, the first policy response would likely be deregulation and devolution. These policy responses were not part of a rational problem-solving process initiated by a new policy problem. They were part of a pre-existing set of policy responses or, at the very least, policy orientation. When policymakers do not have an immediate policy response at hand, they will reach out to the epistemic communities on an issue to see what pre-existing policies are available. An epistemic community can include members of the civil service, researchers, scientists, academics, and interest groups, all of whom have expertise in the study or practice of particular policy issues. Part of this outreach process is applying a filter to see which policies align with the decisionmaker’s ideological position. Almost every member of an epistemic community has ideas about how a policy could be addressed in part or as a whole.

Figure 6-20: Almost every member of an epistemic community has ideas about how a policy should be addressed. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/businesswoman-women-s-power-female-1901130/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Consider these policy solutions as off-the-shelf versus bespoke solutions:

- An off-the-shelf policy solution was created and refined for pre-existing problems. They can be tailored and adapted in a relatively short period of time to address new policy problems.

- A bespoke solution is more akin to the rational and linear conception of policymaking whereby each problem is treated as a unique phenomenon, and a solution is custom-tailored to solve it.

The advantage of off-the-shelf policy responses is that there is a known quantity and therefore entails less risk. Decisionmakers assess risk via technical, economic, and public feasibility:

- Technically, is the policy doable? Technical feasibility is assessed by the amount of resources necessary, the knowledge required to do it, and whether the infrastructure is adequate.

- Economically, is the cost acceptable? Economic feasibility is assessed through a cost-benefit analysis.

- Publicly, is there enough support for the policy? Public feasibility is assessed by public opinion and the willingness of the public to bear the cost of a policy.

Think of the comparison made in the last section on pipeline policy versus clean drinking water for First Nations Reserves policy. The decision to buy the Transmountain pipeline may have been an unusual step, but it passes the test of technical, economic, and public feasibility:

- Technically, a pipeline is a pipeline with a relatively known technical application.

- Economically, it was expensive, but the costs were bearable and would be reduced if/when the pipeline was sold.

- Publically, the pipeline was argued to be a part of the national infrastructure to support resource extraction and, therefore, in the public good.

On the other hand, the provision of clean drinking water on First Nations Reserves is problematic on two or all three of these measurements:

- Technically, each of the 56 Reserves with long-term boil water reserves poses technical problems in creating and maintaining water purification systems.

- Economically, the costs are largely a guess due to the technical challenges.

And, until relatively recently, there was little public support for a large investment in First Nation Reserves.

Figure 6-21: A pipeline. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/woodhead/6792697540/Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Jason Woodhead.

Reason 2: Policy entrepreneurs work independently on policy solutions and potentially on solutions for the future

Second, given the need for policymakers to find feasible solutions in a short period of time, stakeholders will often develop policy solutions for future problems or future implementation. Starting within their own companies, organizations, or bureaucratic divisions, actors will tinker with policy solutions to existing problems and those that could potentially arise in the future. They will share these solutions with colleagues, first informally and later in more formal working groups, presentations, and publications. These ideas will begin to disseminate through their networks to other experts, interest groups, and even to decisionmakers themselves. Key to this process is the concept of policy entrepreneur: those individuals and groups that develop and advocate on behalf of policy solutions. Policy entrepreneurs exist in government, interest groups, social movements, and stand-alone interested actors. They care about policy problems and have devoted considerable energy and resources to potential policy solutions. When a policy problem creates an opportunity, these entrepreneurs advocate on behalf of their policy solution. They will likely be unsuccessful the first time, and their ideas may never catch on. But the longer they persist in tweaking, evolving, and pitching their policy solution, the more likely it will become one of those off-the-shelf policy solutions that policymakers will draw on.

Figure 6-22: Innovation. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/innovation-idea-inspiration-4556696/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain.

Key Takeaway

The most important thing to take away from the policy stream is that it acts independently of the problem stream. It is a separate process of different people in different places seeking to generate solutions to problems that they believe to be important. These policy entrepreneurs exist both inside and outside of the government. They create, join, and participate in networks and organizations that may be narrowly focused, such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, or maybe more ideological, such as the Broadbent Institute or the Fraser Institute. Alternatively, they may be part of a government bureaucracy that provides options for decisionmakers. They all create solutions to existing or potential problems, and they advocate for these solutions with policymakers.

The question now becomes, which policies will policymakers choose to address the problems that have their sustained attention? To answer this question, we need to move to the next stream of the MSA, the politics stream.

Watch Ted Halstead’s TEDTalk “A Climate Solution Where All Sides Can Win” https://youtu.be/ta2Wvy9F_gA

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How is Halstead a policy entrepreneur?

- What is the policy problem he is trying to solve?

- What constitutes his policy network?

- What is Ted Halstead’s policy solution to the policy problem of climate change?

- Traditionally, Republicans have resisted taxation for climate change. How does Halstead seek to soften his approach to be more compatible with Republican decisionmakers?

- In the end, how feasible is Halstead’s plan – Technically, Economically, and Publically?

- To what degree does his plan represent an ‘off-the-shelf’ solution to policy problems?

MSA stream 3: Politics Stream, and a Window of Opportunity

As we have discussed, many policy problems are competing for the attention of decision-makers. There is an equal, if not greater, number of policy solutions seeking problems to solve. The nexus through which both of these streams intersect is the policymaker. A policy problem has to gain the sustained attention of policymakers. A policy solution has to be feasible and acceptable to policymakers. In other words, within the politics stream, policymakers have to be:

- motivated to solve a problem and

- recognize a window of opportunity to solve it.

Political Motivation

Figure 6-23: Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pierre_Elliot_Trudeau-2.jpg#/media/File:Pierre_Elliot_Trudeau-2.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Chiloa.

Policymakers can be motivated by their own personal ideology or that of their political party. They come to a political office with a set of goals they wish to achieve. This is deeply political in that these goals define their political platform and are instrumentally part of the political process. Citizens vote for or against candidates based on this platform. For example, PM Stephen Harper came to office with an overarching goal of limiting the federal government’s reach in Canada. PM Harper would likely be motivated by policy problems that resonated with this ideological orientation.

Policymakers are also motivated by the ‘national mood’, which is the general position held by the public on specific policy issues. The national mood can not be reduced to polling as the national mood represents longer-term attitudes, whereas a poll could represent short-term shifts in public opinion. The national mood is also deeply political in that policymakers are highly sensitive towards shifts in public attitudes, especially those that represent longer-term trends. For example, until the 1960s, the national mood was quite discriminatory towards the LGBTQ community. However, due in large part to the work of pro-LGBTQ advocacy groups, the national mood began to shift. This advocacy would tip into the political world with the comment by then-Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau in 1967 that there was “no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.” In 1969, he decriminalized ‘homosexual acts .’ Since then, a series of legislation has sought greater equality for the LGBTQ communities.

In the 2019 Federal Election, the inability of Conservative leader Andrew Scheer to reconcile his personal beliefs with the national mood on LGBTQ issues was problematic.

Finally, lobbyists and interest groups can motivate policymakers on particular issues. They can highlight the severity of a problem or the potential opportunity a policy solution may represent. They can suggest that their membership would be willing to support a person or party that paid sustained attention to a policy problem important to them or advocated for their policy solution. Those lobbying the government are diverse in form and influence. There are grassroots organizations like Idle No More. There are long-standing interest groups like Greenpeace. There are formal representations such as labour unions (Canadian Union of Public Employees), industry representatives (Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers), and even subnational government organizations (Canadian Federation of Municipalities).

Figure 6-24: Idle No More. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/akrockefeller/9741008837/Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of AK Rockefeller.

All of these groups are not only seeking to influence decisionmakers – that is the literal job of a lobbyist – but they are also building networks. They connect different groups both inside and outside the government that share an interest in particular policy problems and policy solutions. Different networks provide differential access to decisionmakers depending on who is in power. For example, the groups representing organized labour have traditionally had more influence with the NDP and groups representing the petroleum sector have more access to the Conservative Party of Canada. In each case, lobbyists and interest groups will try to highlight policy problems that are important to them and their membership. They will try to suggest policy solutions that will enhance their interests and objectives. The role of lobbyists and interest groups is the definition of politics, trying to influence who will get what and how from that limited pool of resources under decisionmakers’ control.

It is important to add one more point here. In extremis, if policymakers are unable or unwilling to act on policy problems contrary to the national mood, they may find themselves removed from office in the next election. This is the ultimate political check on the process of public policy.

The Window of Opportunity

However, more than just the motivation to act on a policy issue is required to achieve progress. It also requires a window of opportunity. A window of opportunity (or policy window) in the multiple stream approach is space, which may be short-lived, where the problem stream, the policy stream, and the politics stream align. In other words, policymakers have sustained attention on a problem, they have identified a feasible policy response, and there is the political will to carry it through. These three streams come together via coupling to form a window of opportunity. Importantly, a window of opportunity can open in either the problem stream or the policy stream:

- If a window begins to open in the problem stream, there is a consequential coupling: a problem that is looking for a solution. In such cases, policymakers will look to their repertoire of policy responses to see if there is a feasible solution that will have the political backing necessary to carry it through.

- If a window begins to open in the policy stream, there is a doctrinal coupling: a solution looking for a problem. In such cases, the policymaker looks at the problem stream for policy issues to apply their ideological solution.

In either case, when a window of opportunity opens, what had seemed like an intractable problem can suddenly change significantly. Conversely, when a window fails to open, considerable energy can be wasted in trying to force through a policy change.

For example, the election of Donald Trump in 2016 has meant that a variety of policy windows have opened. For those policies that do not require legislative change, President Trump has had considerable success. For example, with the help of the Republicans in Congress and the use of executive orders, President Trump has successfully rolled back, either in part or in full, 85 environmental regulations believed to impede economic growth. For the most part, these are examples of a solution looking for a problem: Trump and Republicans were animated against Federal regulation and were looking for a way to demonstrate their efficacy to their political base. In other areas, like health care reform, President Trump and the Republicans have been largely unsuccessful as they have been moving against the tide of the national mood. While there is only a small point spread between those who approve of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and those who are opposed, there is little agreement on what could or should replace it. In this case, all three streams are in trouble. In the problem stream, it is unclear what policy issue needs a solution. Is it the quality of health care? Access to health care? Is it the public option? There is no agreed-upon replacement to the ACA in the policy stream, most likely due to the lack of clarity in the problem stream. Finally, while there is political support for replacing the ACA by President Trump, the Republicans, and their base, they do not all support the same option. Further, there is weak public support to repeal ACA, especially without a comprehensive replacement. The result has been the failure of President Trump and the Republicans to repeal and replace the ACA.

Figure 6-25: President Donald Trump. Source:https://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/30354791330/in/photolist-NfmeVd-NDDmcA-Nww1xh-MK39tW-MJQMLe-NGQCYF-MJQzua-NGQDVF-MJQCVD-NfkJ13-Nz4f8P-NGQqxi-Nz4cyv-NfkUFS-MJQ73M-NGQpBF-NfkEkC-NGQ3Ng-NfmfoC-NDDv5L-MJQ4D8-NfkBPf-NDDajo-Nfkmf9-NwvYaw-NfksU1-Nz4p8c-NGQzxT-MK3rBo-Nz4kGp-NDD8Fd-MJQdMt-MJQ7PX-LHj5Ed-LjV16A-KPpEFt-LALZK7-KPpVdp-LAM6bs-KPqZ98-LLk8UD-LLk7QV-KPd7aj-KPc6eU-LLk6Bc-KPpYwD-KPcgfq-LjV7eh-LWvCB7-MQUZqq Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Gage Skidmore. |

Figure 6-26: Rally in Support of the Affordable Care Act, at The White House, Washington, DC. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/taedc/32730324780/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Ted Eytan. |

The MSA in Summary

In sum, the MSA offers meaningful insight into the public policy process. For those advocating on behalf of a problem, the MSA provides a fuller picture of what pieces need to be in place to effect change: a clearly identified problem, a doable solution, and the political will to see it through. For a public policy analyst, it allows the disaggregation of the policy process into constituent elements that more closely resembles the reality of policymaking than the rational policy cycle. For the field of comparative public policy, MSA also provides insight, and that is the subject of our last section in this module.

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- Apply the MSA to your public policy issue (i.e., the issue you have chosen to cover in your Podcast and Policy Brief assignments). Describe the following:

- What would constitute the problem stream?

- What would constitute the policy stream?

- What would constitute the politics stream?

- If a policy window has opened, what kind of coupling has occurred?

- If a policy window has not opened, what is impeding it?

Comparative Politics

The multiple stream approach opens up some interesting opportunities for comparative public policy analysis.

First, the MSA has a degree of policy universality that applies to a broad range of policy environments. Kingdon had been looking at the US specifically when establishing MSA, but there is no reason to limit it to the US. When analyzing public policy at the University of Saskatchewan, the city of Saskatoon, the province of Saskatchewan, the federal level in Canada, or even international agreements, there is utility in disaggregating the policy process into the problem, policy, and political streams. More specifically, to the comparative study of public policy, the use of MSA provides a common framework to look at how and why policies have evolved differently in different places and at different times. For example, we could look at how carbon pricing has been dealt with differently provincially in Canadian politics. Was the BC carbon pricing plan a problem in search of a solution? Was the opposition of carbon pricing in Alberta a solution looking for a problem? Can the MSA explain why different windows opened in the two provinces over the same issue?

Figure 6-27: Student climate strike, Vancouver BS, 2019. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/vancouverizer/48812116112/ Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Derek Read.

Second, the MSA provides a different perspective on policymaking that challenges the linear and rational model of decision making. It suggests that many policy problems are looking for solutions. It also suggests many policy solutions are looking for a problem to solve. It highlights how decisionmakers face far more demands for policymaking than is possible. This more chaotic picture of policymaking introduces uncertainty, ambiguity, and competition at the core of agenda-setting. MSA suggests that decisionmakers rarely, if ever, have the time to seek rationally derived policy responses and that they are far more likely to pick policy solutions off-the-shelf. Or conversely, that policymakers may bring their own solutions to the agenda and maybe actively looking for a problem to solve. This chaotic picture of policymaking not only allows researchers to deconstruct policymaking in a variety of polities, but it also allows them to consider why it is different between polities. This recognition of complexity over an ‘ideal type’ of policymaking is useful in every policy context. For example, in China, the Politburo Standing Committee is the preeminent decision making body. It consists of between five and eleven members, including the president and the most influential leaders in China. This body is very opaque and operates in strict secrecy. The degree of influence the PSC wields is dependent on its relationship to the President. However, between the PSC and the President, policy decision making is very centralized. Therefore an interesting question would be to what degree does the centralization of authority in China result in different public policymaking? Does doctrinal coupling almost exclusively drive the window of opportunity for public policy? If so, what happens when a policy is technically challenging but supported by the state?

Figure 6-28: National Emblem of the People’s Republic of China. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:National_Emblem_of_the_People%27s_Republic_of_China_(2).svg#/media/File:National_Emblem_of_the_People’s_Republic_of_China_(2).svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Supreme Dragon.

Finally, the three streams of the MSA allow researchers to compare how problems are identified and measured, how policies are generated and by whom, and how the form and function of the policy windows vary between polities. It allows researchers to compare the particularities of policy development between more centralized polities and more decentralized polities: for example, China, Canada, and the US all have quite distinct institutional pathways of policymaking but must deal with similar policy issues. It allows researchers to compare different forms of multilevel governance: for example, how policymaking in the EU differs from that of the US, Canada, or Germany. In the end, the MSA provides a language and framework with which to compare the complexity of public policymaking: policy problem identification, policy solution generation, policy entrepreneurship, policy feasibility, consequential coupling, doctrinal coupling, and windows of opportunity.

Consider your public policy topic (i.e., the issue you have chosen to cover in your Podcast and Policy Brief assignments). Use the following to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How might the MSA provide insight into how your policy topic evolved differently in a different political context?

- How might the complexity of the MSA provide insight into your policy topic? How might your insight suggest a comparative approach to your research?

Conclusion

This module has sought to accomplish two primary goals.

First, it brought a focus to the role that politics plays in the public policy process. It was argued that politics is an important part of not just public policymaking but also to a vital and healthy democracy. Politics was defined as the authoritative allocation of scarce resources within a given political community. This provides an important insight into the process of public policymaking as decisionmakers need to decide which policies to support and which to pass on – an essentially political act.

Second, in order to better understand the role that politics plays in public policymaking, we introduced the multiple streams approach developed by Kingdon. Kingdon suggested that public policymaking is not as straightforward as the rational and linear approach suggests. Rather, he argues that the process is much more chaotic and that there are many more access points for politics to influence the process. He disaggregated public policy making into three streams that run independently of each other: a problem stream, a policy stream, and a political stream. When these streams come together or couple, a window of opportunity opens for policy development. Unlike the linear approach to public policy. MSA suggests that policy windows can open from the problem stream, aka consequentialist coupling, or from the policy stream, aka doctrinal coupling. In other words, there are problems looking for solutions and solutions looking for problems. But what determines whether a policy is acted on? Importantly, we suggest that the key variable in the multiple stream approach is politics. There is politics involved in what problems receive attention. There is politics involved in the preferred policy solutions of decisionmakers. There is politics involved in the national mood of the political community. There is politics involved in the efforts of policy entrepreneurs, interest groups, and lobbyists to influence decisionmakers.

We concluded the module with the suggestion that the MSA also allows for meaningful comparative analysis. While not intended for anything but the American political process, the MSA can offer meaningful insight into other political contexts and in undertaking comparative analysis. It does so by offering a degree of policy universality that can be applied in different contexts. It provides an alternate framework of analysis than the linear and rational approach to public policy. This allows a comparative analysis that is more reflective of actual policymaking. Finally, it allows researchers to use a language and framework that opens comparative questions about policy entrepreneurship, policy feasibility, and where/how policy windows open.

Review Questions and Answers

The working definition of politics in this course builds on the work of David Easton: politics is the authoritative allocation of scarce resources in a given political community. Or put more colloquially, Harold defines politics: who gets what, when, and how. It is interesting to note how much this definition overlays our working definition of public policy: whatever the government chooses to do or not to do. The government must decide which public policies they are going to commit to providing some of their finite resources. And, by necessity, which public policies they are not going to commit to providing some of their finite resources.

The MSA operationalizes politics in the process of public policymaking. In the problem stream there is politics at work in the competition for the attention of decisionmakers. In the policy stream there is politics at work in the ideological predisposition of decisionmakers and in the epistemic communities seeking to influence them. In the politics stream, there is the national mood, the lobbying efforts of interest groups, and, in the end, the ultimate power of the citizen to overturn government. Finally, the MSA concept of a window of opportunity is important. It suggests that while there are policy problems looking for solutions and solutions looking for problems, it is political will that is determinative.

The problem stream consists of all those policy issues seeking to be included on the institutional agenda of decision makers. These include generic problems that all governments face: how to facilitate economic growth, how to protect the environment, how to balance the budget, et cetera. They also include all of those issues that specific interest groups advocate to be put on the institutional agenda. Finally, they include those policy issues thrust into public view by an external force, a natural disaster or the actions by another state.

In order for a policy process to be addressed, it requires the sustained attention of decision makers. Sustained attention is more likely when a policy problem resonates with a policy solution already in the back of the mind of decision makers. Sustained attention can also be facilitated by a focusing event, a critical moment that brings a policy issue front and centre in the public eye.

The policy stream is where policymakers look to find solutions to those policy problems that they deem worthy of their sustained attention.

The MSA treats the policy stream as independent of the problem stream for two primary reasons. First, achieving progress on policy problems requires the sustained attention of policymakers. We also noted that decisionmakers, by necessity, had to choose which problems to give their attention to, including perennial problems, problems on the systemic agenda, and those problems suddenly thrust into the news from an unexpected crisis. This often means there are insufficient time and resources to generate fully rational policy responses tailored to a specific problem. Rather, policymakers will first draw upon those policy responses, or policy solutions, that are at hand. Some of these will be rooted in their ideological predispositions. When a policymaker does not have an immediate policy response at hand, they will reach out to the epistemic communities on an issue to see what pre-existing policies are available. An epistemic community can include members of the civil service, researchers, scientists, academics, and interest groups, all of whom have expertise in the study or practice of particular policy issues. Part of this outreach process is the application of a filter to see which policies align with the decisionmaker’s ideological position. Almost every member of an epistemic community has ideas about how a policy could be addressed in part or as a whole.

Second, given the need for policymakers to find feasible solutions in a short period of time, stakeholders will often develop policy solutions for future problems or future implementation. Starting within their own companies, organizations, or bureaucratic divisions, policy entrepreneurs will tinker with policy solutions to existing problems and those that could potentially arise in the future. They will share these solutions with colleagues, first informally and later in more formal working groups, presentations, and publications. These ideas will begin to disseminate through their networks to other experts, interest groups, and even to decisionmakers themselves.

The MSA is constituted by three streams: the problem stream, the policy stream, and the politics stream. These three streams come together via coupling to form a window of opportunity. Importantly, a window of opportunity can open in either the problem stream or the policy stream. If a window begins to open in the problem stream, there is a consequential coupling: a problem that is looking for a solution. In such cases, policymakers will look to their repertoire of policy responses to see if there is a feasible solution that will have the political backing necessary to carry it through. If a window begins to open in the policy stream, there is a doctrinal coupling: a solution looking for a problem. In such cases, the policymaker looks at the problem stream for policy issues to apply their ideological solution. In either case, when a window of opportunity opens, what had seemed like an intractable problem can suddenly change significantly. Conversely, when a window fails to open, considerable energy can be wasted in trying to force through a policy change.

Feasibility refers to whether a policy is doable. The MSA uses three measurements of feasibility. Technical feasibility is assessed by the amount of resources necessary, the knowledge required to do it, and whether the infrastructure is adequate. Economic feasibility is assessed through a cost-benefit analysis. Public feasibility is assessed by public opinion and the willingness of the public to bear the cost of a policy.

Glossary

Attention: The amount of notice taken on a particular issue by decisionmakers or other sources of authority

Authoritative allocation: Someone who individually or collectively has the right to decide who is going to get what. In politics, this is often determined through a constitution or some form of legitimation such as elections

Civic disconnect: A lack of resonance or even alienation from both the formal aspects of political decision such as voting and participating in party politics and more informal aspects of engaging in community participation

Consequential coupling: The joining of the three streams (problem, policy, and politics) in the problem stream. It is typified by a problem looking for a solution

Deregulation: The removal or lessening of regulatory frameworks

Devolution: Transfer of power to a lower level of decisionmaking

Doctrinal coupling: The joining of the three streams (problem, policy, and politics) in the policy stream. It is typified by a policy looking for a problem

Epistemic community: A community of people who have expertise in the study or practice of particular policy issues

Feasibility: The likelihood of an action or decision being successful. The MSA focuses on technical feasibility, economic feasibility, and public feasibility

Focusing event: A critical moment that brings a policy issue front and centre in the public eye

Multiple stream approach (MSA): A theory that suggests that the problem, policy, and politics streams must come together for a ‘policy window’ to open and allow for the potential of policymaking

National mood: The general position held by the public on specific policy issues that can be measured and change over time

Off-the-shelf policy solution: A pre-existing policy solution that can be adapted quickly to address similar or new problems

Policy entrepreneur: Individuals and groups that develop and advocate policy solutions for current and future policy problems

Policy universality: A public policy analysis framework that is broad enough to hypothetically cover all policy decisionmaking in all polities

Policy stream (or solution stream): The policy stream is one of three streams in the MSA. The policy stream contains the possible policy solutions. However, counter intuitively, the policy stream of the Multiple Stream Approach is independent of the other two streams, where there may be policy solutions to problems that do not yet exist or may be more ideological in nature.

Policy window: The moment when an issue, a solution, and politics will align to address a policy issue. A policy window can open either in the problem stream or in the policy stream. Also called a ‘window of opportunity.’

Political community: A group of people that are clearly distinguishable by others with some form of institutionalized relationship that can deal with the politics of authoritatively distributing resources under its control.

Politics: The authoritative allocation of scarce resources in a given political community

Politics stream: The politics stream is one of three streams in the MSA. It suggests that the national mood, the lobbying efforts of interest groups, and elections play an important role in shaping the motivation and feasibility of policymaking

Problem stream: The problem stream is one of three streams in the MSA. The problem based stream consists of all those policy issues seeking to be included on the institutional agenda of decision makers.

Rational policy response: An ideal type of policy making that suggests a linear process: a problem is highlighted, a process is undertaken to identify policy responses, the best choice is identified and implemented. Importantly, this rarely matches the policy process in practice.

Scarce resources: The finite amount of policy inputs such as time, money, labour, and natural resources

Sustained attention: When notice has been taken on a particular issue by decisionmakers or other sources of authority in a meaningful and engaged way, with the intention of seeking a solution.

Wicked problem: A complex problem with no easily defined solution because of unclear/shifting problem identification, unknown policy responses, an inability to fit into a broader policy environment, and/or unknown consequences

References

Aldrich, Daniel. "The Fukushima Accident In Social And Political Perspective - Paris Innovation Review". Paris Innovation Review, 2011. http://parisinnovationreview.com/articles-en/nuclear-powers-future-in-japan-and-abroad-the-fukushima-accident-in-social-and-political-perspective.

Birkland, Thomas A. After Disaster : Agenda Setting, Public Policy, and Focusing Events. American Governance and Public Policy. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1997.

Boessenkool, Ken, and Sean Speer. "Stephen Harper’S Open Federalism Changed Canada For The Better". Macleans, 2015. https://www.macleans.ca/politics/ottawa/how-stephen-harpers-open-federalism-changed-canada-for-the-better/.

Boyd, David. No Taps, No Toilets: First Nations And The Constitutional Right To Water In Canada. Ebook. Montreal, Quebec: McGill Law Journal, 2011. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/mlj/2011-v57-n1-mlj1824188/1006419ar.pdf.

Brenan, Megan. "Approval Of The Affordable Care Act Falls Back Below 50%". Gallup, 2018. https://news.gallup.com/poll/245057/approval-affordable-care-act-falls-back-below.aspx.

Confessore, Nicholas. "Koch Brothers' Budget Of $889 Million For 2016 Is On Par With Both Parties' Spending Spending". The New York Times, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/27/us/politics/kochs-plan-to-spend-900-million-on-2016-campaign.html.

DeBardeleben, Joan., and Pammett, Jon H. Activating the Citizen: Dilemmas of Participation in Europe and Canada. Basingstoke [England]; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Easton, D. (1953). The political system, an inquiry into the state of political science. New York, Knopf.

Fisher, Matthew. "Commentary: China Does Not Have To Be Canada's Only Partner In Asia". Global News, 2019. https://globalnews.ca/news/5990102/canada-foreign-policy-china-asia/.

Indian Affairs and Northern Development. Report Of The Expert Panel On Safe Drinking Water For First Nations. Ottawa: Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2006.

Jensen M. (2015) Political Impact of the Fukushima Daiichi Accident in Europe. In: Ahn J., Carson C., Jensen M., Juraku K., Nagasaki S., Tanaka S. (eds) Reflections on the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Accident. Springer, Cham

Jung, Christina. "Neskantaga FN Waits To End Longest Boil Water Advisory As Trudeau Promises To Lift Them All By 2021 | CBC News". CBC, 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/neskantaga-prime-minister-bwa-1.5073496.

Kingdon, John W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. 2nd ed. New York: Longman, 1995.

Lane, Kaycie, and Graham Gagnon. "Opinion: The Lack Of Clean Drinking Water In Indigenous Communities Is Unacceptable". The Globe And Mail, 2019. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-the-lack-of-clean-drinking-water-in-indigenous-communities-is/.

Lasswell, H. Politics: Who Gets What, When, How. 1958

Libin, Kevin. "Kevin Libin: What The West Wants Next". National Post, 2011. https://nationalpost.com/opinion/kevin-libin-what-the-west-wants-next.

Morrison, Val. Wicked Problems And Public Policy. Ebook. Montreal, Quebec: National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy, 2013. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/pdf/publications/1841_Wicked_Problems_Policy.pdf.

Popovich, Nadja, Livia Albeck-Ripka, and Kendra Pierre-Louis. "85 Environmental Rules Being Rolled Back Under Trump". The New York Times, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/climate/trump-environment-rollbacks.html.

Rabson, Mia. "Trans Mountain Pipeline Could Lead To $500M A Year For Clean Energy Projects, Liberals Say". Global News, 2019. https://globalnews.ca/news/6075999/trans-mountain-pipeline-liberals-clean-energy/.

Reich, Simon. "The Four Faces of Institutionalism: Public Policy and a Pluralistic Perspective." Governance 13, no. 4 (2000): 501-22

Rittel, Horst, and W. Webber. "Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning." Policy Sciences 4, no. 2 (1973): 155-69.

Solijonov, Abdurashid. Voter Turnout Trends Around The World. Ebook. Stockholm, Sweden: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2016. https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/voter-turnout-trends-around-the-world.pdf.

"Trudeau: ‘There’s No Place For The State In The Bedrooms Of The Nation’ - CBC Archives". CBC, 1967. https://www.cbc.ca/archives/entry/omnibus-bill-theres-no-place-for-the-state-in-the-bedrooms-of-the-nation.

"Voter Turnout At Federal Elections And Referendums". Elections Canada, 2019. https://www.elections.ca/content.aspx?section=ele&dir=turn&document=index&lang=e.

Zahariadis, Nikolaos. "Ambiguity and Choice in Public Policy: Political Decision Making in Modern Democracies." Public Administration Review 63, no. 6 (2003): 746.

Supplementary Resources

- Béland, Daniel, and Michael Howlett. "The Role and Impact of the Multiple-Streams Approach in Comparative Policy Analysis." Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice18, no. 3 (2016): 221-27.

- Cairney, Paul, and Michael D. Jones. "Kingdon's Multiple Streams Approach: What Is the Empirical Impact of This Universal Theory?" Policy Studies Journal44, no. 1 (2016): 37-58.

- Kingdon, John W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. 2nd ed. New York: Longman, 1995.