Developed by:

Dr. Martin Gaal – University of Saskatchewan

Overview

Figure 8-1: Environmental policy. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/climate-change-earth-globe-2390347/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Noupload.

In Modules 1 through 7, we have been looking at the definition, theories, and levels of analysis at work in the field of Comparative Public Policy Analysis. Module 7 concluded with a look at the impact of globalization and the addition of an international level of decision making on public policy analysis. In the next four modules, we will be looking at specific policy issues in more depth.

In this module, we will be transitioning from a look at the global level of policy making to our first policy issue – environmental policy. This is perhaps the most appropriate policy issue to start with as it is the most ‘global’ of the policy issues we will be looking at. The module will begin with an introduction to the concept of environmental governance and environmental policy. More specifically, we will look at the long history of environmental issues that can be traced back to ancient times and the move towards the contemporary environmental policy context. In the contemporary policy context, we will note the expanding circles of policy making from domestic policy, to bilateral agreements, to multilateral agreements. We will also introduce some specific theories of comparative environmental policy. After introducing environmentalism as a policy area, we will examine it through our frameworks of public policy analysis: the policy cycle, ideas, interests, institutions, the MSA, and critical perspectives. Finally, we close by looking at carbon emissions as an environmental policy issue and suggest some of the ways it can be examined comparatively.

The structure of this module will also frame our next three modules: policy areas, application of policy analysis frameworks, and some suggested means of comparative analysis.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define the field of environmental policy.

- Explain the trends towards globalization (i.e., multi-level governance) and localization in environmental policy, and how this connects to different levels of policymaking (national, bilateral, and multilateral).

- Situate the following concepts within comparative environmental policy: environmental management, environmental justice, postmaterialist value change, Green Theory.

- Critically assess and apply the tools of comparative public policy analysis to environmental policy.

- Environmental policy

- Environmental management

- Bilateral agreements

- Multilateral agreement

- Multi-level governance

- Decentralization

- Industrial pollution

- Development projects

- Existential threat

- Paris Climate Agreement

- Environmental justice

- Postmaterialist Value Change

- Urbanization

- Green Parties

- Green Theory

- Capitalism

- Transnational

- Cosmopolitan

- Carbon emission reduction strategies:

- Cap and trade system

- Carbon tax

- Offset mechanism

- Comparative environmental policy

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

Steinberg, Paul F., VanDeveer, Stacy D. “Bridging Archipelagos: Connecting Comparative Politics and Environmental Politics,” Comparative Environmental Politics – Theory, Practice, and Prospects. Cambridge; London: MIT Press, 2012. [See file in Canvas]

Funke, Franziska and Mattauch, Linus. “Why is carbon pricing in some countries more successful than in others?” Our World In Data, 2018. Available at https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-pricing-popular. [Online link; for Learning Activity 8-4]

Learning Material

Introduction

What is the connection between the environment and comparative public policy? At what level of analysis does environmental policymaking occur? Who are the stakeholders in the debate on environmental issues? How can the local impact and global scale of many environmental concerns be reconciled? These are some of the questions that we are going to tackle in this module.

The module will begin with a bit of substance by addressing the questions ‘what is environmental public policy?’ and ‘how has environmental public policy evolved?’ We will trace the existence of environmental concerns as far back as policymaking records exist. However, we will also note a couple of important nexus points where environmental public policy fundamentally shifted trajectories, such as the mainstreaming of environmental consciousness in the 1960s and the globalization of environmental policy in the 1980s. We will examine the national, bilateral, and multilateral forms of environmental public policy debates. This breadth of policy context, in turn, highlights both the local and global aspects of environmental policy as well as the trends towards multi-level governance and decentralization.

After introducing the topic of environmental policy, we will examine it through our frameworks of comparative public policy analysis: the policy cycle, ideas, interests, institutions, the MSA, and critical perspectives. We will assess the highly polarized interests involved and how they play out in the policymaking cycle. More specifically, we will introduce theories of post-material change, environmental justice, and Green Theory. We will examine the formal and informal institutions that shape the policymaking process. We will finish the module by looking at carbon emission reductions policies in a comparative fashion.

Before moving on, let us assess your knowledge of policy options for global climate change.

Take the CNN Quiz “The most effective ways to curb climate change might surprise you”, found at: https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2019/04/specials/climate-change-solutions-quiz/. Don’t worry if your score is low – this is a tough quiz.

On the following Padlet board, add a post with the following:

- Your score out of 100%.

- One policy that surprised you.

- How we might research that policy option in a comparative way.

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include:

- Your Padlet contribution

- The best Padlet contribution by one of your classmates and why you think this is a strong contribution

What is Environmental Public Policy?

While not entirely new, environmental governance began to take shape in its current form in the late 1960s and 1970s in the developed world. It has rapidly evolved and formed significant linkages with many other government policy areas. This statement does not suggest that governments were not involved in policies that affected the environment before the 1960s – they clearly were. The exploitation of natural resources has long been an aspect of governance – long before developing what we would recognize as an explicit environmental policy. For example, in Canada, think of the explicit constitutional right for provinces to control natural resources and the policy flowing from that, a right grounded in the Constitution Act of 1867. Property law is another example of a policy that impacts the environment that has existed for a very long time.

There are numerous examples of policy decisions having drastic effects on the environment: where cities were built, the decisions for redirecting waterways for human settlement, how garbage and sewage were disposed of, just to name a few. However, the difference between these historical examples and the contemporary policy environment is the concrete and explicit nature of the connection. This explicit connection can be seen in two ways:

- First, contemporary environmental policy often starts from the premise of protecting or regulating the environment and not as a secondary policy concern. For example, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act of 1999 stipulates the Government of Canada must “exercise its powers in a manner that protects the environment and human health, applies the precautionary principle that where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation, and promotes and reinforces enforceable pollution prevention approaches.”

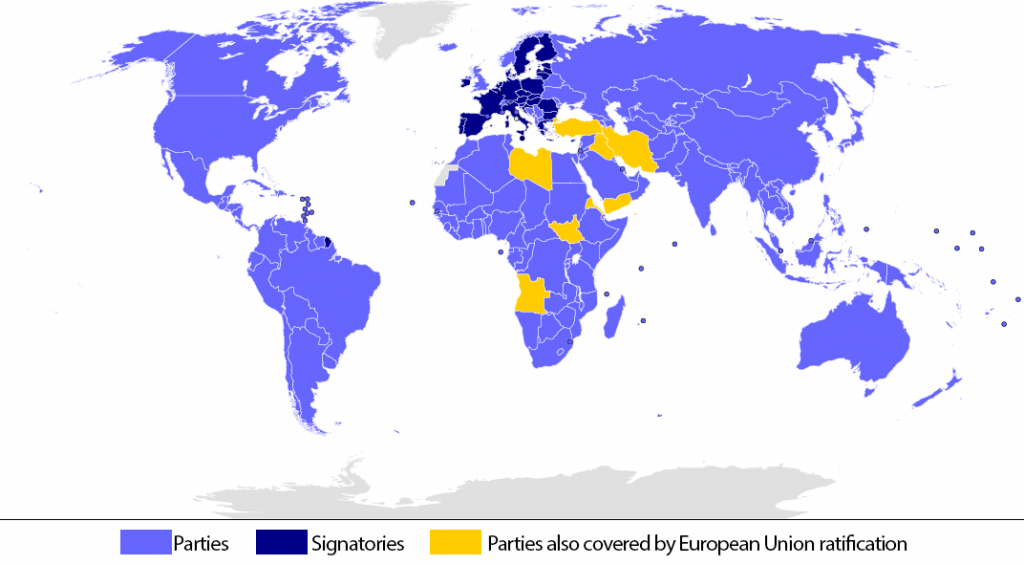

- Second, the explicit connection between the environment and government policy can be seen in the inclusion of environmental provisions in a wide variety of policy areas. This is supported by looking at any newspaper in any city at any time, where we see environmental policy concerns included in the deliberation of economic policy, manufacturing policy, resource extraction policy, urban planning policy, and the list goes on. Environmental policymaking has also gone global, with institutions like the UN playing a role in pushing for environmental agreements, facilitating the drafting of international environmental law, and monitoring environmental compliance. A good example of this is the Paris Agreement, which established goals, monitors progress, and enhances transparency.

Figure 8-2: Signatories and parties to the Paris Agreement. Parties: A state that has given explicit consent to an international agreement Signatories: A state that has agreed to negotiate in good faith towards the goal of an international agreement Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ParisAgreement.svg#/media/File:ParisAgreement.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of L.tak.

The Historical Roots of Modern Environmental Policy

It is useful to look to historical antecedents to understand the place of environmental concerns in contemporary policymaking. There are explicit references to environmental policy in ancient civilizations, for example, the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh (1800 BC) made reference to the divine retribution that occurred for cutting down sacred trees. More specific environmental policy can be found in the Ancient Greek writings of Plato, who noted the impact of deforestation and soil erosion. There is a strong emphasis on ecological balance in many Indigenous world views. In Medieval times, monarchs like King Edward I (1306) sought to fight smog by limiting the burning of coal. In the 18th century, early versions of ‘sustainable development’ began to emerge due to the clear detrimental effects of over-logging. Early in the 20th century, the first signs of comprehensive and coordinated environmental policy in the developed world emerged, seeking to protect “natural endowments” – such as natural parks and reserves. These were conscious efforts to protect the wilderness from the encroachment of human settlement and utilized a discourse that framed the natural world as having intrinsic value rather than simply being a resource for human exploitation. Other early efforts were driven by perceived environmental threats, like the ‘dust bowl’ of the prairies, which was created by poor land management. These are examples that highlight the shifting environmental norms in the early 20th century.

Figure 8-3: Dust storm approaching Stratford, Texas, 1935. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dust-storm-Texas-1935.png#/media/File:Dust-storm-Texas-1935.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of NOAA George E. Marsh Album.

Yet in developed countries, it wasn’t until the 1960s that a broad-based and popular “environmental consciousness” began to coalesce. In the US, two events crystallized this popular adoption of an environmental consciousness:

- Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring; Silent Spring linked the indiscriminate use of pesticides to environmental degradation and, more specifically, the poisoning of the food chain. Carson was essentially arguing we were poisoning ourselves through our economic activity and lack of adequate government regulation.

- The Cuyahoga River fire in 1969 was one of the most polluted rivers in America since it had been a dumping ground for the industrial activity of Cleveland, OH. In 1969, the river caught fire, albeit not for the first time, with flames reaching over five stories high. The fire caught the imagination of the American public and stimulated pressure for the creation of environmental regimes and ministries.

Figure 8-4: The Cuyahoga River fire, 1952. Source: https://clevelandmemory.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/press/id/605/rec/7 Permission: Courtesy of The Cleveland Press Collection, photo credit James Thomas.

This marks the beginning of the modern era of environmental policy. For example, the United States created the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970. A year later, Canada created a ministry for the environment. The creation of these specific departments coincided with a large increase in the amount of environmental policy passed. Since the 1970s, environmental policy has dramatically increased in terms of breadth and depth. In terms of breadth, almost every policy decision in every policy area is now evaluated for its potential environmental impact or requires an environmental assessment. In terms of depth, environmental policy is now being created, supported, opposed, and applied from the most localized grassroots movement to truly global agreements, For example, we see increased advocacy for local sourcing of food to the Paris Climate Agreement.

From Local to Global

Figure 8-5: Logo for United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:UNEP_logo.svg#/media/File:UNEP_logo.svg Permission: Fair Use.

This early mobilization of environmental policy was primarily national and focused on establishing central regulatory institutions for environmental management. The foremost concern of these agencies was to gain control of the ongoing issue of industrial pollution. Slowly the regulations and efforts became more complex and increased in scale. By the end of the 1980s, environmental policy began to focus on the long-term management of environmental burdens and the integration of environmental concerns in other governmental agencies. Perhaps the most important change was the increasing environmental presence in economic policy by national decision-makers. It is also notable that the list of stakeholders also broadened to include business interests, NGOs, social movements, and epistemic communities at both the domestic and international levels.

While this early mobilization of environmental policy was national in nature, it is wrong to conclude there was no international component. Environmental issues do not recognize borders. In 2011, when the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor melted down in Japan, the radiation did not stop at borders, nor did the radiation from the Chernobyl reactor nearly 30 years before that. Climate Change, one of the most pressing contemporary policy issues, is truly global. And we have known the mechanics of ‘global warming’ since Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier published on the subject in 1822 and Nils Gustaf Ekholm coined the term ‘greenhouse effect’ in 1901. Important international actors include global environmental NGOs like Greenpeace, founded in 1969, and the UN, which created the United Nations Environmental Programme.

However, even internationally, most early environmental policy was localized between bordering states and resulted in bilateral agreements such as the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty signed between Canada and the United States to resolve the use of shared waters. Things began to change in the 1980s, especially with the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986, which highlighted the global context of environmental policy, and the signing of the Montreal Protocol in 1987, a multilateral agreement to combat the hole in the ozone layer by agreeing to a comprehensive ban on the use of Chlorofluorocarbons. Events such as these played a similar role that Carson’s Silent Spring did in the 1960s, in that they facilitated the expansion and mainstreaming of global environmental networks and established a nascent global environmental consciousness.

Figure 8-6: Global Climate March, Berlin, 2015. Source: https://flic.kr/p/Bu4NLJ Permission: Fair Use.

The above argument implies that environmental problems can be highly localized or globalized, both in terms of the geographical impact of the problem as well as the cause. A single industry polluting a particular river is a localized environmental problem. This becomes international when borders are crossed, like the Canada US Boundary Waters Treaty and global when it affects the entire planet, like anthropogenic climate change. Therefore, environmental problems operate at many different environmental scales, and the policy responses are multiscale themselves. For instance, in the United States, cities and states have responded to a Federal Government that has dragged its feet on climate change policy by adopting numerous ambitious policies that reflect local contexts. This, in turn, has increased pressure on that higher level of Government to act. For example, US states like California have enacted environmental policies that have forced other states and the Federal Government to react. Dalton, Recchia, Rohrschneider (2003) surveyed environmental groups worldwide. They found widespread engagement with the Government at national and local levels, suggesting that environmental NGOs do not ignore subnational levels of Government in their advocacy. This has meant social actors need to use multi-level advocacy with cross-border collaboration between NGOs. Similarly, MNCs and IGOs use multi-level advocacy and coalition building. Environmental policy is now operating at every level of decision making, from municipalities, local NGOs, and businesses, to IGOs, global NGOs, and MNCs.

Figure 8-7: Indigenous youth protest. Source: https://flic.kr/p/2hYRB1Z Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of John Englart.

Watch David Wallace-Wells TEDTalk “How we could change the planet’s climate future” https://www.ted.com/talks/david_wallace_wells_how_we_could_change_the_planet_s_climate_future?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How does Wallace-Wells describe the current Climate Change challenges that we face?

- Why does he argue this is not a problem of centuries but a problem of his generation?

- Why does he argue there is a silver lining to this challenge?

- Why does he argue the obstacles to achieving solutions to climate change are human ones?

- A core argument in the TEDTalk is about transformation with new technology, new infrastructure, and, ultimately, new politics. Considering this,

- What do you think this means for public policymaking?

- How might the two trends of environmental policy, globalization and localization, shape policymaking in the future?

Trends in Environmental Public Policy

Globalization

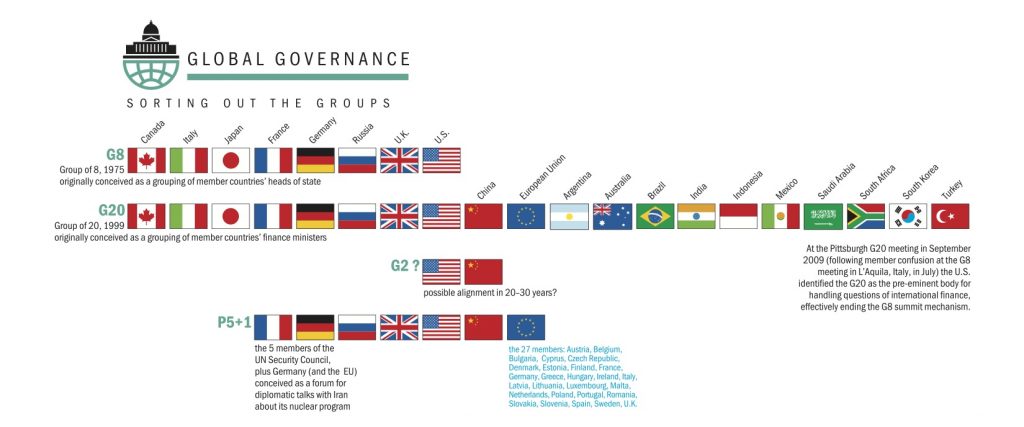

One trend of environmental policy is towards multi-level governance. National governments remain the privileged actors in politics both in terms of domestic policy and global governance. Environmental policy is not excluded from this. However, just like many other policy areas, there are pressures from above and below that make environmental policy more multi-level. On the one hand, there is a trend for regulatory responsibilities to be increasingly directed to the international level by the forces of globalization. This makes sense given the challenge things like pollution pose to borders or the impact of local emissions on global changes to climate change.

The most formal example of an environmental policy above the sovereign state can be found in the European Union, where environmental regulations and standards have taken a supranational character. In the EU, the European Commission manages many environmental policy areas, which takes a lead role in drafting and monitoring regulations and directives. The supranational aspect of environmental policy in the EU means that France, Germany, or Poland must abide by these policies regardless of their domestic political interests or constraints. At the interstate level, multilateral agreements have been signed to tackle problems that are global in nature, for example, the aforementioned Montreal Protocol (1987), the troubled Kyoto Protocol (1997), and the current Paris Climate Agreement (2015). Working in the background are a number of international bodies, like the UN Environmental Program, which seek to share scientific knowledge, monitor state compliance, and model environmental outcomes. These are all examples of the increasingly international nature of environmental policymaking.

Figure 8-8: Global governance – sorting out the groups. Source: https://flic.kr/p/cRvDh9 Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Future Challenges.

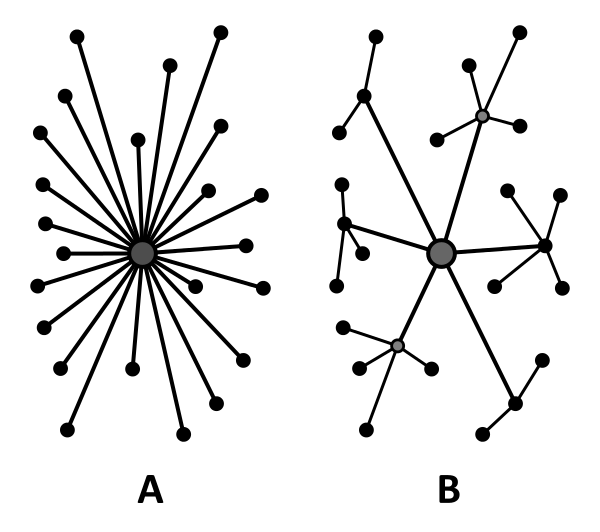

Decentralization

Figure 8-9: Centralized (A) and decentralized (B) systems. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Decentralization_diagram.svg#/media/File:Decentralization_diagram.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Kes47 (?).

The globalization of environmental policy has also been accompanied by a second trend, whereby environmental decision-making processes are decentralized. Instead of looking to the international level, national governments have been transferring a great deal of authority over environmental issues to local provinces, townships, and local user groups. Decentralization of environmental policy occurs when a problem is localized, or the solution to the problem is best found or managed by local decisionmakers. Local decision-making can be more efficient when local actors better understand the context and/or the different policy instruments at their disposal. Decentralization can take several forms. It can be the decentralization of political authority whereby local polities can make and implement policy. The decentralization of policy can also be administrative, where localized agents are given responsibility for implementing the policy. Finally, decentralization can shift decision making from the public to private actors through privatization or deregulation.

These two trends of globalization and decentralization, taken together, illustrate both the complexity of environmental policymaking and the immense role for comparative public policy analysis.

Watch Christiana Figueres and Chris Anderson’s TEDTalk ” How we can turn the tide on climate” https://youtu.be/NUFEBioLPf8

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- How does the video highlight the two trends involved in environmental policy?

- Use Canada as the base unit of analysis and pick one of the five policy solutions introduced in the video: power, built environment, transport, food, and re-greening the earth. Discuss:

- What is the international aspect of the policy solution?

- What is the national aspect of the policy solutions?

- What is the local aspect of the policy solution?

- What are the opportunities and obstacles presented by the multilevel aspect of these environmental policy solutions?

Applying the Frameworks of Comparative Public Policy Analysis

Turning back to our frameworks and theories of comparative public policy analysis, let us see how they apply to global environmental policy. Recall the following frameworks from earlier modules:

- The Policy Cycle

- The roles of Ideas, Interest, and Institutions

- The Multiple Stream Approach (MSA)

- Critical Perspectives

- Comparative Public Policy

Let’s look at each of these more closely.

1. The Policy Cycle

In Module 7, we discussed how globalization’s institutions, practices, and processes complicate policymaking. Globalization has introduced a new policymaking level, with international institutions claiming some policymaking space, empowering new actors, and raising new issues. All of these are relevant to global environmental problems and can be seen in the policy cycle, most notably in the agenda-setting, decision making, and evaluation stages.

The Agenda-Setting Stage

Figure 8-10: The Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River, China. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ThreeGorgesDam-China2009.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Le Grand Portage.

In the agenda-setting stage, environmental issues took a more prominent place in the systemic agenda in the 1960s and 70s, with individuals and interest groups pressuring their respective governments to tackle localized issues. In developed countries, these localized issues were often about industrial pollution or nuclear power. In developing countries, local issues were often opposed to large development projects, especially around hydroelectric power such as the Three Gorges Dam in China and the Yacyreta Dam located between Argentina and Paraguay. However, we should also note this opposition to infrastructure projects is not strictly a developing country issue, as is evident in Canada with the notable opposition to the James Bay project in Quebec and the Site C project in BC. From the 1980s onward, this environmental pressure has globalized, partly in reaction to issues and events that demonstrated the global implications of environmental issues – think back to the examples of the Chernobyl nuclear accident and the threat of UV radiation created by the hole in the ozone layer. More recently, the globalization of environmental policy has been driven by the global impact of deforestation, air/water pollution, increased recognition of Indigenous rights and the impact on Indigenous peoples, and global impacts like global warming and climate change. However, it was also driven by environmental NGOs and the epistemic community that identified and advocated for solutions to global environmental issues like ozone depletion, global warming, climate change, the dangers of nuclear power, and Indigenous rights. These activists and policy entrepreneurs have been largely successful in that environmental issues have moved to the institutional agenda in most states on most issues. Moreover, this activism is increasingly global in nature, with environmental NGOs and networks connecting people worldwide and through the institutions of global governance, like the UN. However, this success is qualified in that many issues, while recognized, have not been adequately addressed, at least not by the standards of their advocates.

The Policy Formulation and Decision-making Stages

Figure 8-11: A sandblasting truck works next to a pipeline. Source: https://flic.kr/p/bveYnZ Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Jason Woodhead.

At the policy formulation and decision-making (i.e., policy adoption) stages, environmental concerns are recognized, and environmental activists are heard. However, they represent one voice of many and are advocating for one issue that impacts many. Decision-makers are also being pressured by other actors, most notably business interests. They need to weigh the costs of the environmental issues/policies against other competing interests such as employment, taxation, and social welfare. This is problematic for environmental activists as they believe their issues to be an existential threat, and half-measures will fail to address their concerns. It is also problematic for decision-makers since they need to balance the multiple and, at times, incommensurate demands being made by their constituents.

For example, pipelines are a politically contentious issue in Canada. Environmental advocates see the approval of more or expanded pipelines as a betrayal of Canada’s commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement since such capacity building facilitates a greater carbon footprint. Advocates of the energy industry see the failure to approve more or expanded pipelines as a betrayal of the workers and companies in the oil and gas sector and the provinces who depend on resource royalties. Indigenous peoples and their advocates in Canada are divided between those who see pipelines as an environmental threat to Indigenous lands and those who see pipelines as a means for economic empowerment. These tensions are embedded in a wider societal debate around Canada’s role as an energy power and environmental actor.

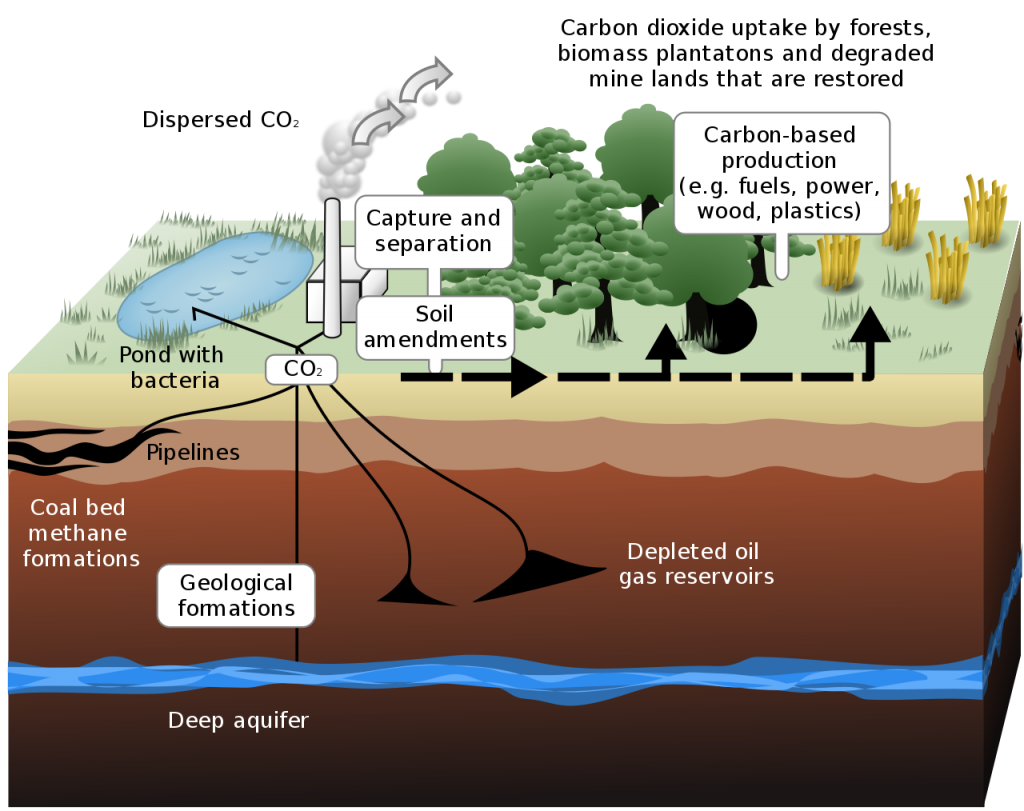

The Policy Evaluation Stage

Many of these tensions come to a head in the evaluation stage of the policy cycle. An administrative evaluation will judge whether a policy has met its intended purpose, whether an explicit environmental goal or an environmental regulatory component in another policy area. For example, the University of Saskatchewan may evaluate whether its sustainability policies meet its projected goals and at the projected cost. The Province of Saskatchewan would take a similar process on its Carbon Sequestration project, the Canadian Government on its carbon pricing policy, and the UN Environmental Program on the Paris Climate Agreement. These evaluations are primarily internal by nature, but different political jurisdictions will have different rules on how these evaluations are released.

Figure 8-12: Schematic showing both terrestrial and geological sequestration of carbon dioxide emissions from a biomass or fossil fuel power station. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carbon_sequestration-2009-10-07.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of LeJean Hardin & Jamie Payne. Woodhead.

More public and more contentious are judicial evaluations. For example, the provinces of Alberta, Ontario, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan have all challenged the constitutionality of the Federal Government’s carbon pricing policy. The Supreme Court of Canada may uphold the carbon policy as constitutional or strike it down either in part or whole. This will not only deeply influence carbon policies, but it will also be fodder for political evaluations, which we will discuss in the next section. While there is no world court for judicial evaluation of environmental policies, IGOs do monitor and report on the progress of national policies to meet agreed to standards such as those agreed to in the Paris Climate Agreement and will also feed into political evaluations, albeit less influentially than those of the courts. International monitoring also includes keeping an eye on national judicial evaluations as this will impact whether countries can meet their global commitments.

Figure 8-13: The Supreme Court of Canada. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Nine.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of James McCaffrey.

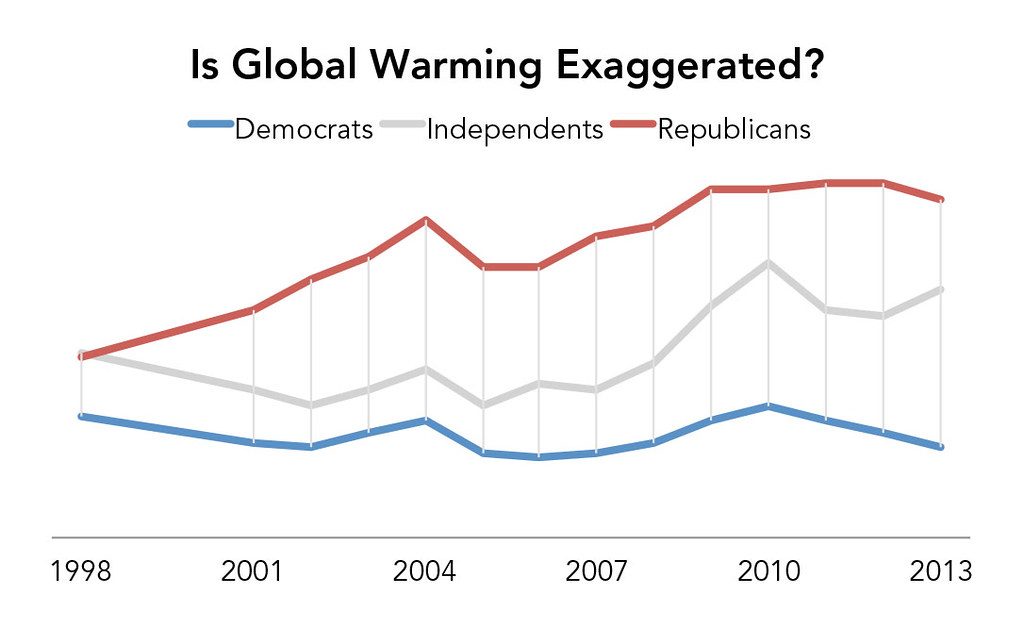

For many policy areas, especially contentious areas such as the environment, policymakers are keenly aware of the importance of political evaluations. Political evaluations refer to the assessments taken by all stakeholders, particularly political parties, to ‘take the measure’ of the public. In the case of Canada’s carbon pricing policy, the Federal Government will seek to assess the opinions held by the nation at the aggregate level, provincial variations, and key constituencies. The provinces will undertake a similar review but at the provincial and municipal levels. NGOs and MNCs will seek to influence the public mood and therefore influence the political evaluation of policies. At the international level, IGOs, NGOs, MNCs and countries all play a two-level political evaluation. They are monitoring the public mood in key countries. For example, when dealing with environmental policy, the US, China, India, and the EU are important as they represent key economic actors, institutional players, and populations. In the end, political evaluations can often be the key variable that determines what types of environmental policies are put in place and how robust they are in terms of design and practice.

Figure 8-14: Poll results for “Is global warming exaggerated?” Source: https://flic.kr/p/eqbNoi Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Third Way Think Tank.

2. The roles of Ideas, Interest, and Institutions

Ideas

Figure 8-15: An Amazon UK warehouse. Source: https://flic.kr/p/vKxjC Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of D K.

There has always been a strong ideational component of environmental policy. Early environmental advocacy pushed back against powerful cognitive paradigms like the industrial revolution and modernity. These paradigms shaped a narrative of humanity sitting atop a world of bounty ready for the taking, to be transformed through science and innovation into products that would tame the wildness of the world. Early advocates like the Sierra Club or the National Audubon Society challenged these ideas by positing that nature had its own intrinsic value. Carson’s work, Silent Spring, challenged the idea that industrialization and modernity were benign to our well-being. The Chernobyl nuclear meltdown, ozone depletion, global warming, and climate change were, and are, used to challenge the idea that environmental policy is a national issue. These cognitive challenges have also posed troublesome to normative frameworks, especially in the West and/or Global North. Actors like the EU and Canada are troubled by how their environmental policies at home and abroad are dissonant to their image of being good international citizens. Advocates for change frame this dissonance to challenge the world culture defined by resource extractions, global supply chains, and mass consumerism.

Figure 8-16: The National Black Environmental Justice Network at a demonstration. Source: https://flic.kr/p/pkEBSJ Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Joe Brusky.

One interesting idea used to frame global environmental policy is environmental justice. This is central to the environmental movement and involves two critical ideas: fair involvement and fair treatment. Fair involvement means that the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws rightfully involve all people they could impact. Fair treatment means that no group of people, whether defined by race or socioeconomic factors, should bear the unequal burden of the environmental problems caused by environmental policy.

The idea of environmental justice entered mainstream discourse in 1982 when community members in the largely African-American Warren County, North Carolina, were protesting the disposal of PCB-tainted soil in a new landfill. This protest saw long-standing civil rights organizers join forces with environmental activists, creating a new coalition that influenced one another. Civil rights organizers criticized the environmental organization’s leadership for being largely white and for perceiving the environment as “wilderness,” as something apart from humans and in need of protection. They argued the environment should instead be perceived as something where people “live, work, and play”, and that activism needed to focus on how environmental risks threaten the everyday life of ordinary people and how poor and racialized people disproportionately felt these risks. This included various injustices, such as unequal enforcement of existing laws meant to protect them, higher levels of exposure to harmful environmental degradation, and practices that excluded their meaningful participation in decision-making practices regarding these policies.

This idea of environmental justice has also become a central plank in demands for global policy responses to the threat of climate change since the worldwide distribution of the causes and problems of climate change are unequally distributed. Small states and some developing states tend to be low carbon emitters and are nonetheless highly vulnerable to the predicted impacts of a warming climate. Think of small island states, like the Maldives or Tuvalu and Nauru, that exist close to sea level and could potentially be inundated by rising sea levels. Attempting to mitigate such risk is not only prohibitively expensive, but it could also pose an existential threat. The costs of climate change will be borne unequally between states and also by people within states. Climate instability, such as heatwaves, increased air pollution, flooding, or other hardships, will disproportionately affect those without the resources to migrate those impacts. Moreover, potential policies meant to reduce carbon emissions might have a doubly negative impact on marginalized or precarious groups. For example, increased energy costs due to a carbon pricing policy will largely be borne by communities least able to absorb the increases. For environmental justice, a policy meant to address the unequally distributed risk of climate change must not unequally distribute the burden of addressing it.

Figure 8-17: Malé, capital of Maldives. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Male-total.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Shahee Ilyas.

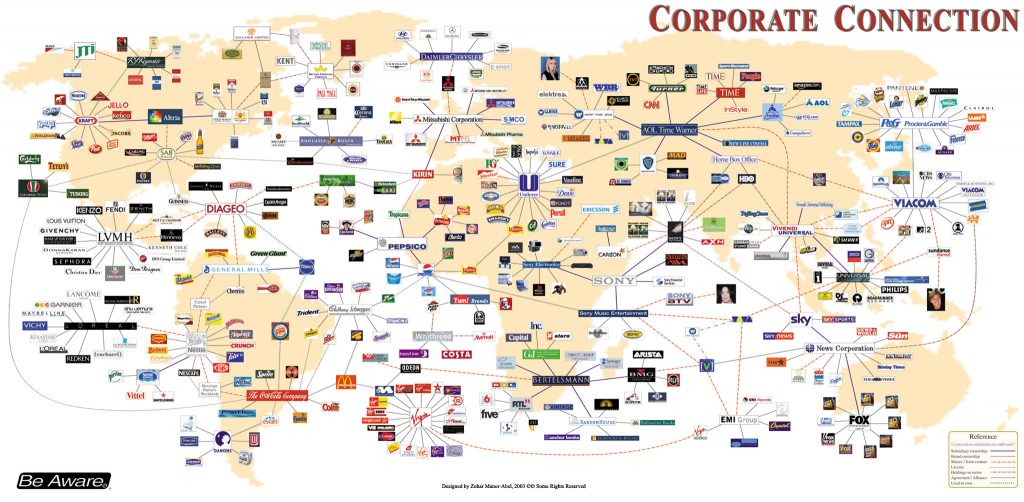

Interests

Most environmental policies are driven by advocacy rooted in people’s interests. This is because most environmental problems are highly localized in their impact. People feel it where they live or are worried about how it will impact where they live. These environmental problems can also start locally, such as industrial pollution, the effluent that created the Cuyahoga River fire, or soil erosion from deforestation. Other environmental problems are regional, such as the impact of the Fukushima reactor meltdown or acid rain, while others are global, such as ozone depletion, global warming, or climate change. Yet even the regional or global environmental problems have a localized impact. In addition, there is a class dimension of environmental impact, as those who pay the costs of environmental problems tend to be disproportionately less wealthy and less powerful. This means that the mobilization of social interests is a key aspect of environmental politics. In order to protect their interests, those affected by environmental problems have mobilized to oppose practices, laws, or conditions they deem to be unfair or immoral. And those who benefit from the environmentally damaging practices or who are unwilling to pay the cost of mitigating environmental challenges will, in turn, push back against their advocacy. Some of these environmental problems include those that negatively impact health, and these environmental health issues usually require collective action to respond to. This is another reason why social mobilization and non-state actors are key to the study of environmental politics.

Figure 8-18: Corporate connections. Source: https://flic.kr/p/9Afpv Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Zohar Manor-Abel.

Figure 8-19: Generational change. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/the-eleventh-hour-time-for-change-1156776/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Alexas_Fotos.

Ronald Inglehart’s theory of Postmaterialist Value Change, published in his 1977 book The Silent Revolution, is an influential theory that explains why environmental interests change or rise in prominence. Inglehart broadly based his theory on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The idea is that an individual will first prioritize those things that are in short supply. However, in the absence of material scarcity, an individual will prioritize “post-materialist” values, such as freedom of speech, quality of life, or environmental protection. This shift of values occurred in developed countries during the post-war economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s, which partly explains why Carson’s book was so catalytic in 1969. Developing nations, in contrast, often still place more value on “materialist” needs. China’s 2017 policy banning the importation of material waste, particularly plastics, is an interesting test case for Inglehart’s theory. As China became wealthier and the environmental impact of industrialization became harsher, the Government has rebalanced policy priorities away from wealth towards environmental protection. However, this theory has been challenged by a wave of recent scholarship that has been unable to find empirical evidence to support the notion that the citizens of less-developed states place less importance on environmental issues. In some cases, there is evidence suggesting the exact opposite. Indeed, increasing levels of environmental activism worldwide in both developed and developing countries have been accompanied by public sentiments of concern for those matters. The health of environmental systems is increasingly a global interest of both developed and developing countries. Like we suggested in Module 3, this might also reflect the internalization of a world culture that has embraced environmental concerns.

Institutions

The three institutional approaches introduced in Module 3 provide insight into environmental policy.

Figure 8-20: Path dependency. Source: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/arrows-direction-production-planning-1577983/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Historical institutionalism makes a persuasive argument that certain critical junctures have shifted the path of environmental policy. For example, early 18th century problems like industrialization and urbanization motivated policy responses for waste management and early 19th-century environmental advocates sought to protect natural spaces by creating national parks. In the 1960s, industrial waste and concerns over human health created the context for the modern environmental movement. In the 1980s, fears of nuclear meltdowns and ozone depletion facilitated global environmental policies. These critical junctures are nexus points where the path dependency of environmental policy shifts dramatically.

Rational choice institutionalism is useful in explaining the intent, and the struggle, behind the global framework for environmental governance. The Montreal Protocol, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Climate Agreement have all tried to institutionalize environmental policy that shifts what rationality entails. This means trying to curb the ‘tragedy of the commons’ by finding agreement on norms, monitoring compliance, and building trust between actors. This was largely successful in the Montreal Protocol but largely failed in the Kyoto Protocol. The relative success and failure of each can be explained by the simplicity and certainty in the Montreal Protocol and by the complexity and uncertainty in the Kyoto Protocol. At a more general level, this tension is due to the lack of supranational authority that can enforce global environmental policies. Yet, we still see how both formal and informal institutions influence expectations of behaviour and shape rationality calculations.

Figure 8-21: Influence. Source: https://flic.kr/p/9iiK4b Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Sean MacEntee.

This leads to sociological institutionalism. Domestically, we have seen an internalization of environmental norms, as demonstrated by every kindergarten child chanting “reduce, reuse, and recycle.” There is a ‘logic of appropriateness’ at work that demands that we individually and collectively seek ways to protect the environment. Internationally, there is growing pressure to find solutions to global environmental problems like climate change. For individuals, we hear the mantra of ‘think global but act local.’ States face mounting pressure both domestically and from global activists to agree upon and meaningfully enact environmental policy. Yet, while such norms have become embedded in most countries, these norms compete with economic interests and clash with localized cultural practices as well as global practices of consumerism. This has led to tension between what is expected and what has been delivered.

Figure 8-22: Act local, think global. Source: https://flic.kr/p/CqK2eN Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Kevin Dooley.

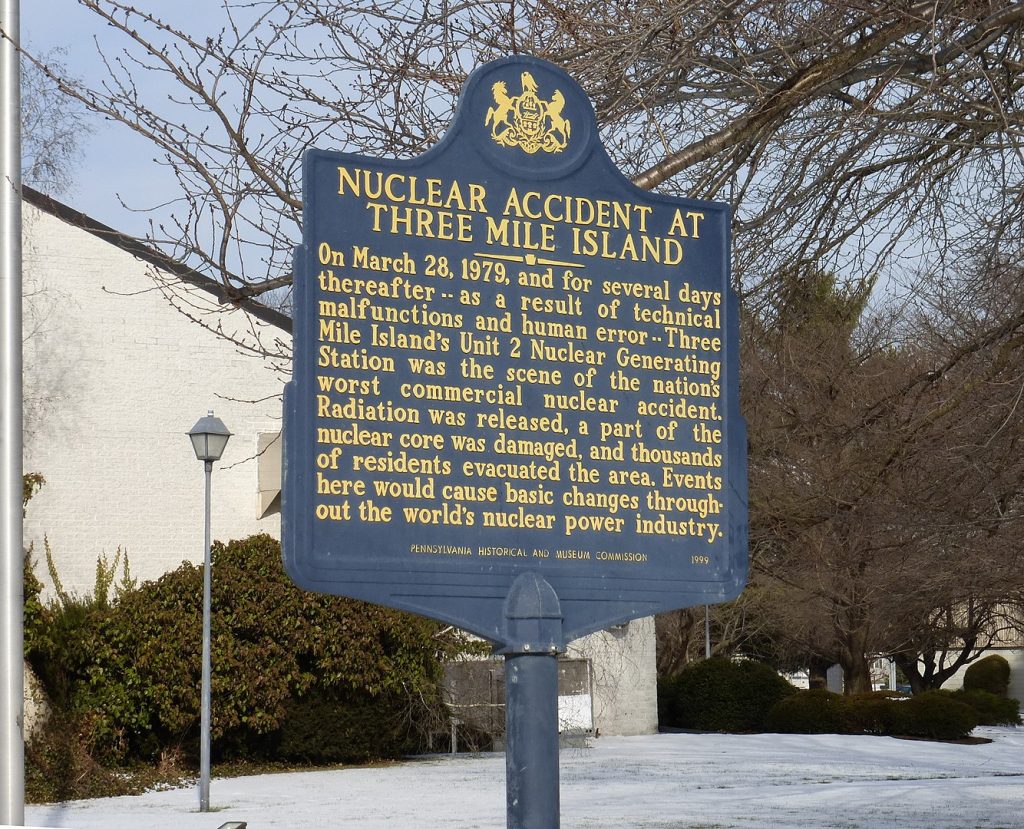

In all of this, perhaps the most visible sign of the institutionalization of environmental concerns can be seen in the global rise of Green Parties, the increased prominence of environmental NGOs, and the internalization of environmental regimes. The number of Green Parties worldwide is a striking testament to the institutionalizing of environmental policy. It demonstrates how political parties have internalized environmental views and the increasing importance of environmental ideas within traditional partisan politics. Green Parties have been increasingly supported by and acted in concert with environmental NGOs. Generally, environmental NGOs tend towards being ‘outsider’ groups, but with Green Parties, these NGOs are often core parts of their institutional structure. They bring voting blocks to Green Parties, advocate in the general public for environmental issues, and monitor and hold accountable both Green Parties and the Government of the day on environmental policies. The output from the rise of Green Parties and environmental NGOs can be seen in the laws, regulatory practices, and enforcement tools embedded in environmental regimes. For example, Scruggs (2003) looked at the performance of political institutions related to the environment. He used quantitative analysis of environmental performance in 17 wealthy democracies, comparing pollution levels, waste management, and clean water, to national wealth, economic structural changes, concern for the environment amongst the public, ENGO activities, etc. However, quantitative analysis of institutional impact is less common as there is often a weak deterministic response to environmental problems. For example, what is even defined as an environmental policy problem? Values and culture very much influence policy problems – for instance, Gamson and Modigliani (1989) note the partial nuclear meltdown at the Michigan Enrico Power Generating Station in 1966 was considered a technical issue for the experts to solve. However, Rochon (1998) notes the response to the Enrico case was not empowered by organized critics of nuclear power. In contrast, when a nuclear accident occurred at Three Mile Island in 1979, the response was highly critical and contextualized as a sustained policy problem. The difference between the two responses was largely due to changes in values and political culture around environmental issues that had been institutionalized both informally and formally in the US.

Figure 8-23: A sign in Middletown, Pennsylvania describing the Three Mile Island accident. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Three_Mile_Island_accident_sign.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Z22.

3. The Multiple Streams Approach (MSA)

Figure 8-24: Planning to frame the debate. Source: https://unsplash.com/photos/vbxyFxlgpjM Permission: Public Domain. Photo by You X Ventures on Unsplash

In the Multiple Streams Approach (MSA) to public policymaking, the key is identifying if a policy window has opened to facilitate a policy response. A policy window is opened when a problem receives sustained attention, viable policy responses have been identified, and the political calculus supports action. There are numerous examples of policy windows opening for environmental issues. We have mentioned several of these already, for example, policy responses to air pollution, industrial waste, risks to our food supply, nuclear accidents, ozone depletion, global warming, and climate change. In each of these cases, all three streams were present, leading to opening a policy window. For example, the processes of global warming and climate change had begun to be recognized as an environmental problem as early as the end of the 19th century. Possible policy responses to global warming and climate change have existed almost as long: from the work of Guy Callendar in 1938, where he demonstrated the link between CO2 emissions and global warming, to the prescriptions of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change formed in 1988. However, for a policy window to open, there needed to be a focusing event that would lead to sustained attention. In the case of global warming and climate change, these include ozone depletion, melting polar ice caps, rising sea levels, changing weather patterns, and extreme weather events. When all three streams come together, a policy window opens, and policy responses are possible: for example, the Montreal Protocol, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Climate Agreement.

However, the extended timelines that connect human behaviour and adverse climate events create a problem for environmental advocates. How to identify focusing events and foster sustained attention on the issue by policymakers? In response, environmental activists have explicitly sought to apply the insight of the MSA. As Rose et al. (2017) argue, environmental policy entrepreneurs have four means to use the MSA. They can:

- Foresee and prepare for emergent policy windows;

- Respond quickly when unexpected events open a policy window;

- Frame knowledge by aligning environmental narratives with contemporary events;

- Persevere in closed policy windows.

In so doing, environmental policy advocates are consciously using the MSA to push their policy agenda forward now and are prepared to do so in the future.

4. Critical Perspectives

Figure 8-25: A man protests against corporate fascism. Source: https://flic.kr/p/AK1jV9 Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Alisdare Hickson.

From a critical theory perspective, environmental policy is deeply intertwined with issues of power, privilege, and coercion. For the most part, critical theory perspective questions ‘what is’ and suggests ‘what should be.’ In terms of global environmental policy, we can trace critical approaches through Green Theory.

Green Theory has evolved in two phases. In the first phase, Green Theory coalesced in western developed states and questioned the idea of human chauvinism and advocated for a more eco-centric view of the world: in other words, they challenged the idea that only humans have intrinsic worth. This began in the 1960s and facilitated the growth of a sub-culture that challenged the role of capitalism, imperialism, and unfettered economic growth at all costs. The second wave was more transnational and more cosmopolitan. In this second wave, Green Theory embraced environmental justice, looking at the variability of costs and benefits of existing economic, political, and social institutions. This is deeply embedded in questions of class, dominance, and power. Green Theory seeks to expose how the wealthy and powerful put in place and defend ideas, processes, and institutions that meet their interests. Green Theory suggests policy alternatives that produce more equitable outcomes both for people and for ecosystems.

5. Comparative Public Policy

What would a comparative research program on environmental policy look like? There are a number of possibilities since environmental policy can be both localized – meaning local pollution causing local impact, and nested – meaning that local pollution aggregates across communities to have a global impact. For example, local coal-fired electric generators may harm local air quality, but it also contributes to global carbon emissions and, therefore, global climate change. Taken together, this means there many potentially fruitful means to undertake a comparative analysis. The first step is to identify what you are seeking to compare: for example, a policy problem, a policy process, or a policy outcome. The second step is to find a meaningful comparison to offer policy suggestions and defend this choice. In undertaking a comparative policy analysis, you will have to identify the similarities, the differences, and the frame of reference for your analysis.

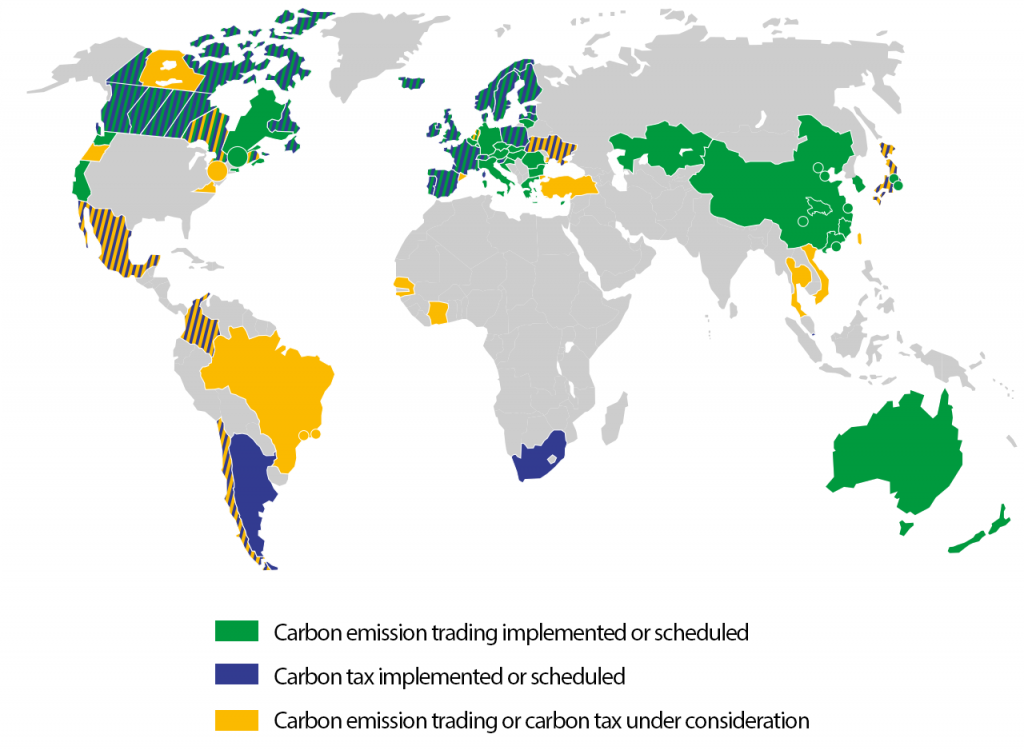

In terms of environmental policy, there is a wide variety of potential comparative approaches. Let us take carbon emissions as an example policy issue. In terms of policy mechanics, you could make a technical comparison of the different types of carbon emission reduction strategies:

- A cap and trade system where emitters can buy and sell emission units to meet needs.

- A carbon tax that sets a price on the amount of carbon emissions.

- An offset mechanism where companies can invest in environmental projects outside their own company and count the reduction in GHG emissions against their own emissions.

- A regulatory requirement for carbon emission accounting in the project approval process.

Such a technical comparison would allow you to identify the most effective carbon reduction policy in a given jurisdiction.

Alternatively, you could compare the implementation of carbon emission reduction strategies across different jurisdictions, for example, by comparing the application of carbon pricing in British Columbia versus Quebec, two jurisdictions that implemented their own carbon emission plans. Or you could compare BC’s voluntary carbon pricing system against the imposed carbon pricing system in Saskatchewan. You could also compare different national approaches to carbon emission reduction policies, for example, by comparing Canada to Australia or the UK. In each suggested comparison, you would be able to identify similarities and differences in how the respective policy windows opened and possibly closed, how policies were deliberated, selected, implemented, and evaluated. It would be possible to look for cultural, economic, political, and institutional factors that influenced or even explained the similarities and differences. Unpacking these processes would allow for the identification of the ideas, interests, and institutions at play. For example, was the voluntary nature of BC’s carbon pricing policy rooted in cognitive paradigms particular to BC versus SK? Are there informal institutions at work in BC and SK that influenced the receptiveness to carbon pricing? How about more formal institutional factors, like the differences in relations between each province and the Federal Government? Are interest groups at work in shaping the form and function of carbon pricing policies and opposing said policies? Similar questions can be framed in national comparisons, for example, between Canada and the US. It is also possible to compare individual national policies with the norms, processes, and policy prescriptions at the international level. It is possible to evaluate national or even provincial or state policies with international commitments to particular policy goals.

Figure 8-26: Carbon emission trading and carbon tax around the world (2019). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carbon_taxes_and_emission_trading_worldwide_2019.svg Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of World Bank Staff and contributors.

In sum, comparative environmental policy is a significant and growing area of policy research, given the importance of the environment to the lives of human beings. The most relevant research examines how policy can be used to manage the increasing number of environmental problems caused by human activity. However, the sort of problems that must be dealt with and the sort of human activity related to them are exceedingly complex and diverse. In order to make sense of these differences, CEP must utilize theory to make sense of these complex and diverse issues to draw larger conclusions by comparing across jurisdictions. Yet, utilizing theory does not overcome the importance of differences between cases. Quite the opposite: by comparing politics across jurisdictions, we can understand the importance of the political context in determining political outcomes. This approach sits somewhere between theoretical generalization and contextual particularism.

If you haven’t already, read Franziska Funke and Linus Mattauch’s post, “Why is carbon pricing in some countries more successful than in others?”: https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-pricing-popular

Read “Energy Education: Carbon Tax vs Emissions Trading” Carbon tax vs emissions trading – Energy Education

Next, use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- Why do the authors argue carbon pricing is the most effective means to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement on mitigating global climate change?

- Why is political acceptability the biggest challenge of the passage and preservation of ambitious carbon pricing policies?

- Using the material from the readings, suggest a comparative public policy research project on carbon policy pricing using either the MSA or a Critical Perspective.

Conclusion

This module has sought to introduce environmental issues as a comparative public policy issue. We looked at the historical background to environmental policy and how the contemporary policy context emerged from localized issues like industrial pollution to bilateral issues like boundary waters and global issues like ozone depletion and climate change. These shifts imply that environmental policy is diverse, complex, and inherently multi-level. We noted the two trends in environmental public, the trend towards international or even supranational policymaking and the trend towards more decentralized and localized policy making.

We then looked at environmental policy through our frameworks of public policy analysis: the policy cycle, ideas, interests, institutions, the MSA, and critical perspectives. We noted the clear impact of the global influence on environmental policy through the policy cycle in the agenda-setting, formulation, decision-making, and evaluation stages. We noted the diversity of actors involved and the existential nature of the debate for many of these stakeholders through each of these stages. Next, we noted the deeply ideational basis of environmental policy debates and specifically introduced the concept of environmental justice. In terms of interests, we noted the sharp clash between groups seeking to influence environmental policy. More specifically, we examined the theory of postmaterialist value change, which suggests environmental interests are correlated with a constituency’s wealth. In terms of institutions, we noted how formal and informal institutions shaped the form and function of environmental policy nationally and internationally. We noted the rise of Green Parties and environmental NGOs as evidence of institutional shifts in environmental policymaking. In terms of the MSA, we noted the importance of when and how policy windows open to facilitate environmental policymaking. From a critical perspective, we introduced Green Theory and the linkages between the environment and capitalism/imperialism. This led to the adoption of environmental justice at the global level as a critique of the status quo institutions.

We closed this module with a look at potential comparative research on carbon emission reduction policies. In fact, of all the issues we will cover in this course, the environmental policy offers perhaps the broadest range of policy comparison. This breadth is grounded in the fact that every policy is, to a greater or lesser degree, struggling with similar problems, and one policy’s actions can have a dramatic impact on another.

Review Questions and Answers

Environmental management is focused on creating national regulatory institutions to deal with processes and outputs which create local environmental issues. The move towards environmental management arose out of the context of the rising environmental consciousness in the 1960s and 70s driven by things like Carson’s Silent Spring and the Cuyahoga River fire. This consciousness brought a spotlight to the negative impact of industry on the environment. This led to the formation of formal governmental institutions for the environment. For example, the United States created the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970. A year later, Canada created a ministry for the environment. The creation of these specific departments coincided with a large increase in the amount of environmental policy passed. Since the 1970s, environmental policy has dramatically increased in terms of breadth and depth. This increased breadth and depth has moved environmental policy from discrete bodies that manage environmental issues to being incorporated in almost every policy area.

In terms of environmental policy, the national level of policymaking is privileged. This is because the impact of environmental policy is always felt somewhere and the state has the resources, authority, and often legitimacy to craft and enforce a policy response. Think of the pollution emitted by factories that created the Cuyahoga River fire. However, environmental issues do not respect borders. When the impact of environmental issues crosses one border, an effective response requires two states to come to a bilateral agreement. Think of Boundary Water Treaty signed between Canada and the US in 1909. When environmental issues impact multiple states, an effective policy response requires three or more states to come to a multilateral agreement. Think of the Montreal Protocol or the Paris Climate Agreement.

Environmental policy has moved towards multi-level governance, with two embedded trends. The first trend is for global regulatory responsibilities to be increasingly directed to the international level by the forces of globalization. This makes sense given the challenge things like pollution pose to borders or the impact of local emissions on global changes to climate change. The most formal example of environmental policy above the sovereign state can be found in the European Union, where environmental regulations and standards have taken a supranational character.

The second trend is defined by the decentralization and localization of environmental decision-making. Instead of looking to the international level, national governments have been transferring a great deal of authority over environmental issues to local provinces, townships, and local user groups. Decentralization of environmental policy occurs when a problem is localized, or the solution to the problem is best found or managed by local decisionmakers. Local decision making can be more efficient when local actors have a better understanding of the context and/or the different policy tools at their disposal.

Environmental justice is defined by involves two critical ideas: fair involvement and fair treatment. Fair involvement means that the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws rightfully involve all people that could be impacted by them. Fair treatment means that no group of people, whether defined by race or socioeconomic factors, should bear the unequal burden of the environmental problems caused by environmental policy.

This idea entered mainstream discourse in 1982 when community members in the largely African-American Warren County, North Carolina, were protesting the disposal of PCB tainted soil in a new landfill. This protest saw long-standing civil rights organizers join forces with environmental activists, creating a new coalition that began to influence one another. Civil rights organizers criticized the environmental organization’s leadership for being largely white and for perceiving the environment as “wilderness,” as something that was apart from humans and in need of protection. They argued the environment should instead be perceived as something where people “live, work, and play,” and that activism needed to focus on how environmental risks threaten the everyday life of ordinary people, and the way in which these risks were disproportionately felt by poor and racialized people. This included a variety of injustices, such as unequal enforcement of existing laws meant to protect them, higher levels of exposure to harmful environmental degradation, and practices that excluded their meaningful participation in decision-making practices regarding these policies.

Environmental justice became more transnational and cosmopolitan when incorporated as a central plank of Green Theory and in response to the inherent inequality of climate change impact. Small states and some developing states tend to be low carbon emitters and are yet nonetheless highly vulnerable to the predicted impacts of a warming climate. Think of small island states, like the Maldives or Tuvalu and Nauru, that are close to sea level and could potentially be inundated by rising sea levels. Attempting to mitigate such risk is not only prohibitively expensive, but it could also pose an existential threat. This is not only limited to how the costs of climate change will be borne unequally by states, but also by those within states. Climate instability, such as heatwaves, increased air pollution, flooding, or other hardships, will disproportionately affect those without the resources to migrate those impacts. Moreover, potential policies meant to reduce carbon emissions might have a doubly negative impact on marginalized or precarious groups.

Ronald Inglehart’s theory of Postmaterialist Value Change is loosely based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The idea is that an individual will first prioritize those things that are in short supply. However, in the absence of material scarcity, an individual will place more importance on “post-materialist” values, such as freedom of speech, quality of life, or environmental protection. This shift of values occurred in developed countries during the post-war economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s, which partly explains why Carson’s book was so catalytic in 1969. Developing nations, in contrast, often still place more value on “materialist” needs. China’s 2017 policy on banning the importation of material waste, and in particular, plastics, is an interesting test case for Inglehart’s theory. As China became wealthier, and the environmental impact of industrialization became harsher, the Government has rebalanced policy priorities away from wealth towards environmental protection.

However, this theory has been challenged by a wave of recent scholarship that has been unable to find empirical evidence to support the notion that the citizens of less-developed states placing less importance on environmental issues, or in some cases, has found evidence suggesting the exact opposite. Indeed, increasing levels of environmental activism across the world in both developed and developing countries have been accompanied by public sentiments of concern for those matters. The health of environmental systems is increasingly a global interest of both developed and developing countries. Like we suggested in Module 3, this might also reflect the internalization of a world culture that has embraced environmental concerns.

Comparative Environmental Policy is a significant and growing area of policy research given the importance of the environment to the lives of human beings. The most relevant research examines how policy can be used to manage the increasing number of environmental problems that are caused by human activity. However, the sort of problems that must be dealt with and the sort of human activity related to them are exceedingly complex and diverse. In order to make sense of these differences, CEP must utilize theory to make sense of these complex and diverse issues, in order to draw larger conclusions by comparing across jurisdictions. Yet utilizing theory does not overcome the importance of differences between cases. Quite the opposite: by comparing politics across jurisdiction, we are able to understand the importance of the political context in determining political outcomes. This approach sits somewhere between theoretical generalization and contextual particularism.

Glossary

Bilateral agreement: An agreement made between two countries. In terms of environmental policy, bilateral agreements usually arise over boundary issues like waterways that cross borders or when the actions in one country create negative impact in a neighbouring country.

Cap and trade system: A system of emissions reduction whereby an absolute ceiling on emissions is established and actors whose emissions fall below this cap can sell them to those actors who will exceed the cap.

Capitalism: A form of social organization that privileges private ownership of the economy. In terms of environmental policy, capitalism plays an important role both in two ways. From the perspective of the ‘tragedy of the commons’, capitalism can lead to the over use of common resources and is also suggested as a means to solve the ‘tragedy of the commons’ by suggesting privatisation. From a critical perspective, capitalism has had a coercive impact on the globalization of environmental degradation by privileging consumerism and the exportation of pollution from advanced economies to developing and under-developed economies.

Carbon emission reduction strategies: Any policy intended to lower carbon emissions. In terms of environmental policy, carbon emission reduction strategies are deeply connected to a country’s international commitments to climate change.

Carbon tax: A direct levy placed on greenhouse gas emissions, usually priced per tonne.

Comparative Environmental Policy: The field of study which juxtaposes environmental policy in different jurisdictions to find and assess similarities and differences that explain the deliberation, shape, implementation, and effectiveness of particular policies.

Cosmopolitanism: The idea that all human beings have moral obligations, and for stronger advocates political obligations, based on their humanity.

Decentralization: The transfer of power or authority from the national or central actor to subunits or more localized actors.

Development projects: Seek to provide economic growth in a state. In terms of environmental policy, development projects can come with a high environmental cost.

Environmental justice: Based on two ideas: fair involvement and fair treatment. Fair involvement means that the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws rightfully involve all people that could be impacted by them. Fair treatment means that no group of people, whether defined by race or socioeconomic factors, should bear the unequal burden of the environmental problems caused by environmental policy.

Environmental management: Constituted by the formal institutional arrangements that seek to reduce environmental harm, like the Canadian Ministry for the Environment.

Environmental policy: Can be one of two things. First, it can be the rules put in place by the state for the regulation or protection of any activity with an environmental impact. Second, it can be the rules and/or general orientation of a private organization, most often a company or NGO, to regulate their environmental impact.

Existential threat: A threat to the very survival of something. In terms of environmental policy, the strongest ecological advocates argue that anything less than radical change threatens the survival of a species, including human beings.

Green Parties: A political and institutional response to environmental threats and the coalescing of environmental consciousness. Green Parties became most influential in Europe and emerged in the 1970s and become mainstream in the 1980s, especially after the Chernobyl accident, particularly in Germany.

Green Theory: An environmental variant of Critical Theory, that highlights the structural and coercive nature of the existing economic, political, and social systems, including capitalism, development, and consumerism.

Industrial pollution: The pollution of air, water, soil, food, from industrial activity.

Multilateral agreement: An agreement made between at least three countries and can include all countries. In terms of environmental policy, the most significant multilateral agreements include the Montreal Protocol, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Climate Agreement.

Multi-level governance: Defined by centers of authority and decision-making existing both above and below the state. In terms of environmental policy, multilateral governance is reflected in the trends towards the global influence on policy and the decentralization/localization of policy.

Offset mechanism: A system of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by allowing actors to invest in environmental projects outside their own company and count the reduction in GHG emissions against their own emissions.

Paris Climate Agreement: A 2015 agreement made by COP21 (Conference of the Parties) to the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, that brought all parties into consensus on limiting global temperature change to 2 Degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Further, the parties agreed to pursue a limit of 1.5 Degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Postmaterialist Value Change: A theory that suggests environmental interests are correlated with a constituency’s wealth.

Transnational: A descriptor for a group, network, action, or policy that extends beyond a single state. In terms of environmental policy, this can refer to the networks and social movements that formally or informally work together to advocate on environmental issues.

Urbanization: Describes the movement or trend of people moving from rural and small localities to larger cities.

References

______, Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999. Government of Canada. S.C. 1999, c. 33 https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-15.31/page-1.html

_____, What is the Paris Agreement?, 2018. United Nations Climate Change.https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/what-is-the-paris-agreement.

____, What is Carbon Pricing? The World Bank Accessed on 21 April 2020. https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/what-carbon-pricing.

Brook, Ted. Climate change and Canadian federalism: Examining the constitutional dispute sparked by Parliament’s Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act. Norton Rose Fulbright. October 1992. https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en-ca/knowledge/publications/7b195ef7/climate-change-and-canadian-federalism.

Bullard, Robert D, Glenn S. Johnson. 2000. "Environmental Justice; Grassroots Activism and Its Impact on Public Policy Decision Making". Journal of Social Issues. 56(3): 555-578.

Carraro, Carlo, and Francois Leveque. Eds. 1999. Voluntary Approaches in Environmental Policy. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Cashore, Benjamin, Graeme Auld, and Deanna Newsom. 2004. Governing through Markets: Forest Certification and the Emergence of Non-state Authority. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dalton, Russell J. 1994. The Green Rainbow: Environmental Groups in Western Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dalton, Russell J., Steve Recchia, and Robert Rohrschneider. 2003. The Environmental Movement and the Modes of Politics Action. Comparative Political Studies 36 (7): 743-771.

Dryzek, John S., David Downes, Christian Hunold, and David Schlosberg. 2003. Green States and Social Movements: Environmentalism in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dunlap, Thomas. 1999. Nature and the English Diaspora: Environmental History in the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Gamson, William A., and Andre Modigliani. "Media Discourse and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power: A Constructionist Approach." American Journal of Sociology 95, no. 1 (1989): 1-37.

Hochsetler, Kathryn. 2002. After the Boomerang: Environmental Movements and Politics in the La Plata River Basin. Global Environmental Politics 2 (4): 35-57.

Inglehart, Ronald. The Silent Revolution : Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1977.

Jasanoff, Shelia. 2005. Designs on Nature: Science and Democracy in Europe and the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Luton, Gary. A Historical Survey of Canadian International Treaty Diplomacy. Canada in International Law at 150 and Beyond. Paper No. 18 — March 2018. https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/Reflections%20Series%20Paper%20no.18_Luton.pdf.

O'Neill, Micheal. 2012. Political Parties and the "Meaning of Greening" in European Politics. In Comparative Environmental Politics: Theory, Practice, and Prospects. London: MIT Press.

Oud, Nicole. First Nations renew legal fight against Site C dam after talks end with B.C. government. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/first-nations-renew-legal-fight-against-site-c-dam-after-talks-end-with-b-c-government-1.5261815.

Ribot, Jesse C. 2002. Democratic Decentralization of Natural Resources: Institutionalizing Popular Participation. Washing, DC: World Resources Institute.

Rochon, Thomas R. Culture Moves : Ideas, Activism, and Changing Values. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Rose, David C, Nibedita Mukherjee, Benno I Simmons, Eleanor R Tew, Rebecca J Robertson, Alice B.M Vadrot, Robert Doubleday, and William J Sutherland. "Policy Windows for the Environment: Tips for Improving the Uptake of Scientific Knowledge." Environmental Science and Policy, 2017, Environmental Science and Policy.

Schlosberg, D. and Collins, L.B. 2014. "From environmental to climate justice: climate change and the discourse of environmental justice". WIREs Clim Change, 5: 359-374.

Schreurs, Miranda A. 2005. Environmental Policy-Making in the Advanced Industrialized Countries: Japan, The European Union and the United States of America Compared. In Environmental Policy in Japan, ed. Hidefumi Imura and Miranda A. Schreurs, 315-341. Northampton, Mass.: The World Bank/Edward Elgar.

Scruggs, Lyle. Sustaining Abundance: Environmental Performance in Industrial Democracies. 2003.

VanDeveer, Stacy D., and Ambuj Sagar. 2005. Capacity Development for the Environment: Broadening the Focus. Global Environmental Politics 5 (3): 14-22

Verhoke, Sam. Power Struggle. The New York Times Magazine. 12 January 1992. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/01/12/magazine/power-struggle.html.

Vidal, John. Why is Latin America so obsessed with mega dams? The Guardian. 23 May 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/may/23/why-latin-america-obsessed-mega-dams.

Wapner, Paul. 1995. Politics beyond the State: Environmental Activism and World Civic Politics. World Politics 47 (3): 311-340.