Developed by:

Dr. Martin Gaal – University of Saskatchewan

Overview

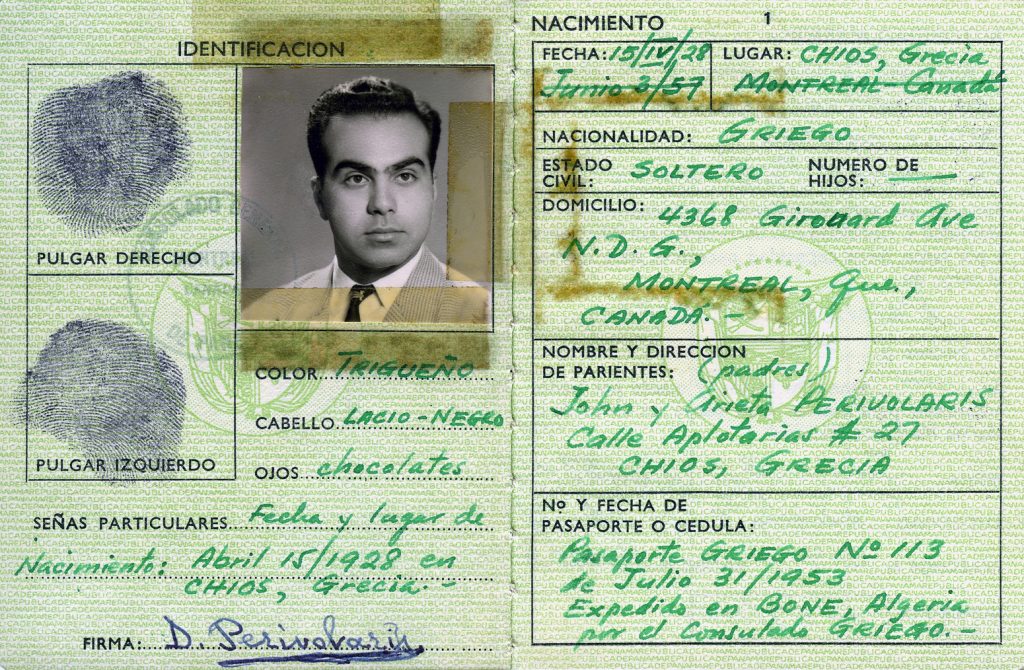

Figure 9-1: ID Issued by the Panamanian Consulate, Montreal, Canada, 1957. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/dr_john2005/2587236104/ Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of John Perivolaris.

In the last module, we applied our frameworks of comparative public policy to the issue of environmental policy. We noted that environmental policy was polarized in nature, with little middle ground, creating a dilemma for policymakers.

In this module, we turn to another contentious policy issue and one with an international dimension but with a distinctly more national decision-making context: immigration and citizenship. Immigration and citizenship is perhaps an even thornier issue area for decisionmakers than environmental policy as it speaks to issues of belonging, identity, rights, and obligations. The positions that people hold on immigration and citizenship can be quite intractable. Some perceive immigrants as a threat to jobs and a threat to cultural homogeneity. For others, immigrants are a necessity to balance an ageing demographic and to fill gaps in the labour market that locals are unwilling to do. Still, others see immigration policy as a humanitarian obligation and a means to offer refuge to those at risk from persecution or struggling to survive human-made or natural disasters. Even the terminology used in debates on immigration is loaded and contentious. Those who are more pro-immigration use terms like refugee, irregular migrant and asylum seeker. Those who hold more anti-immigration views tend to use terms like illegal migrant, economic migrant, and even potential terrorists. These debates are further embedded in a global dialogue on the rights of migrants and the application of international humanitarian law. Policymakers find themselves caught in this debate between competing narratives of immigrants as a threat, as an opportunity, and as a humanitarian responsibility.

Therefore, in this module, we will start with an overview of immigration as a policy issue and contextualize this with the Canadian example. Next, we will look at immigration as a public policy issue, both as a standalone case study and as a systemic study of immigrants and immigration processes. Finally, we will examine immigration policy through the frameworks of comparative public policy covered in this class so far: the policy cycle, the role of ideas/interests/institutions, the multiple streams approach (MSA), and critical perspectives. We will close the module with some examples of comparative public policy research on immigration policy.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define the field of immigration policy.

- Operationalize the concepts of push factors and pull factors in migration.

- Explain the narratives of migration and immigration in Canada and more generally.

- Situate the domestic and international influences on immigration policy.

- Critically assess and apply the tools of comparative public policy analysis to immigration policy.

- Immigration

- Citizenship

- Humanitarian obligation

- Persecution

- Refugee

- Irregular migrant

- Asylum seeker

- Illegal migrant

- Economic migrant

- Sovereignty

- Borders

- Permanent residents

- Push factors / Pull factors

- Sending states / Receiving states / Transition states

- Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program (PSR)

- Case study approach

- Immigration control

- Immigration integration

- Immigrant-settler states

- Proximity

- Public perception

- Contact theory

- Social level indicators

- Threat theory

- Jus soli / Jus sanguinis

- Global Compact on Migration

- Read the Required Readings assigned for this module.

- Proceed through the module Learning Material, completing any additional readings and watching any videos in the order presented.

- Complete the Learning Activities as you encounter them. Some of these will prompt you to complete written responses in your Learning Journal (see Canvas for more details).

- Review the Learning Objectives and the Key Terms and Concepts for this module. Check any definitions with the Glossary.

- Complete the Review Questions and check your answers against those provided. If you have additional questions, please contact your instructor.

- Use the Supplementary Resources sections at the end of this module for further information.

- Check the Class Syllabus for any additional formal Evaluations due or graded activities you must submit.

Freeman, Gary P. “National Models, Policy Types, and the Politics of Immigration in Liberal Democracies.” West European Politics 29, no. 2 (2006): 227-47. Available at https://library.usask.ca/scripts/remote?URL=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01402380500512585?casa_token=z-OZZieklM8AAAAA%3AicGzaEJzDLPQQm-Map0a9nGLmSTXHvFLS_V76zsYh4Vbr18H-Pi4Y0LW3RQCTpfdrgHeKUkaX8ozjgo [Online]

Anne Gallagher. “We need to talk about integration after migration.” World Economic Forum, 2018. Available at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/10/we-need-to-talk-about-integration-after-migration/ [Online; for Learning Activity 9-4]

Sergi Pardos-Prado. “What’s the best way to integrate immigrants.” The Conversation, 2017. Available at https://theconversation.com/whats-the-best-way-to-integrate-immigrants-reward-effort-and-dont-make-their-lives-difficult-83679 [Online; for Learning Activity 9-4]

Learning Material

Introduction

Public policy operates across a broad range of policy contexts and issues. Decisionmakers deal with local pollution policy, regional employment policy, provincial health care policy, national gun policy, and international climate policy. This diversity highlights how policy guides and determines so much of the lives of citizens within a country. An essential characteristic of the state, something that distinguishes it from other actors, is the possession of sovereignty. A sovereign state infers that no higher authority can legally compel the state to act. Sovereignty also requires clearly defined geographic borders, and it is the state’s responsibility to police and defend these borders. Therefore, a state has the sole legal authority and responsibility to deal with the complications that arise from its geographical borders, including the natural migration flows of human beings.

This responsibility raises all kinds of important policy questions. Under what conditions should outsiders be permitted to cross the border and enter the country? What national and international norms and laws regulate what outsiders can do within the state if admitted? Can they become citizens? If so, what is necessary to do so? How does the existing citizenry feel about this? Does it matter where the prospective citizens come from? What benefits can new citizens and those applying for citizenship have access to? These questions highlight the contentious nature of immigration and citizenship policies.

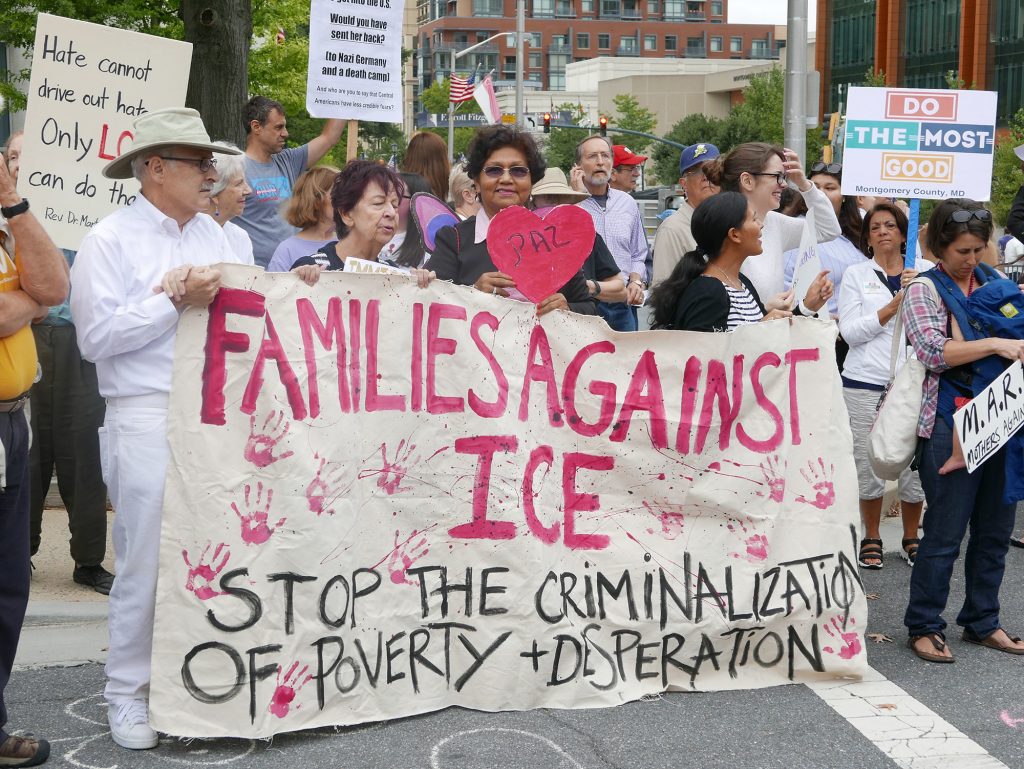

Contemporary immigration and citizenship policies have become even more contentious with current events: the perceived threat of terrorism and the resulting fear of outsiders post 9/11; the large increase of irregular migration to Europe following the Syrian Civil War in 2015; the impact of President Trump’s immigration crackdown on irregular migration flows to Canada; the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Events such as these have raised the stakes in immigration and citizenship debates. Yet, at the same time, the developed economies require skilled labour. Many are faced with declining and ageing populations, which suggests a need for a more liberalized immigration policy. Policymakers often find themselves stuck between anti-immigrant and pro-immigrant advocacy groups.

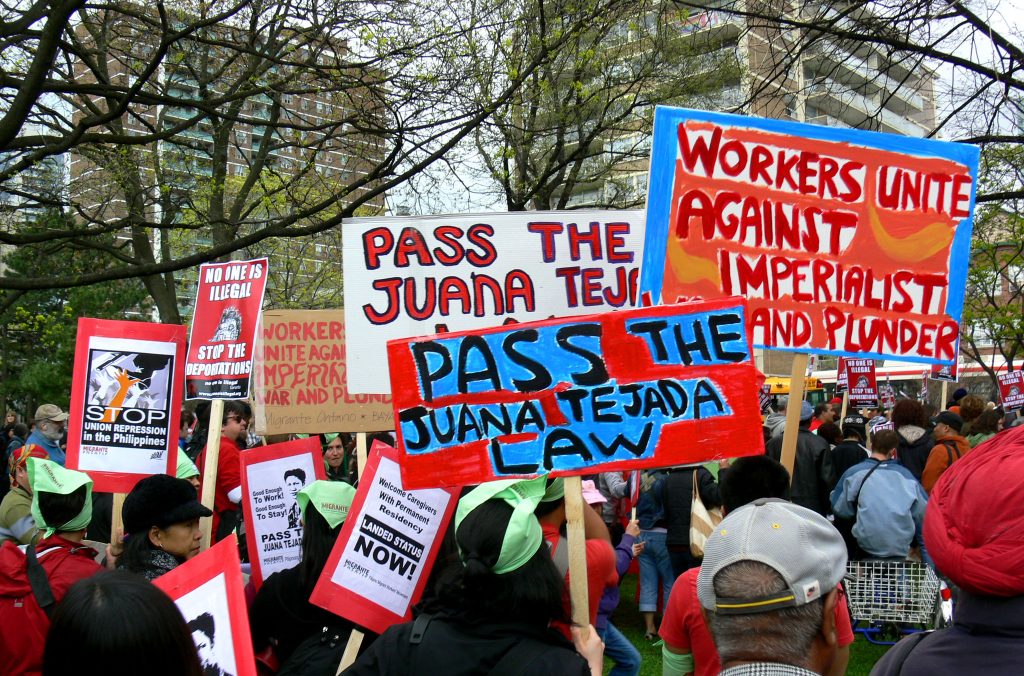

Figure 9-2: Anti-immigration. Source: https://flic.kr/p/o71tyL Permisson: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of A Jones. |

Figure 9-3: Pro-immigration. Source: https://flic.kr/p/2hf3ux3 Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Susan Melkisethian. |

Before moving on, let us assess how much you know about immigration to Canada.

Take the Canadian Citizenship test: http://canada-citizenshiptest.com/free-canadian-citizenship-hard-questions.php

On the following Padlet board, add a post with the following:

- Your score out of 20.

- Did any of the questions surprise you?

- Do you think these are good examples of things that prospective Canadian citizens should know? Why or why not?

In your Learning Journal, you will need to include:

- Your Padlet contribution

- The best Padlet contribution by one of your classmates and why you think this is a strong contribution

Immigration Policy and the Canadian Context

Immigration policy is, at root, the terms and conditions by which the state will admit foreigners into its borders. Not all foreigners seeking entry are immigrants, as most people crossing borders do so for a limited duration. For example, some may be seeking to enter the country as tourists or for business purposes. Others may be seeking to enter the country for a significant duration but may not be staying permanently, such as students or those arriving for a temporary family reunion. Immigration policy pertains to those seeking to enter the country to become permanent residents (PR) or full citizens. Permanent residents have the right to reside in the receiving state for an undefined duration as long as they adhere to the rules and maintain their status. Those seeking citizenship are applying to become full and equal members of the state they seek to enter. The differences between a permanent resident and a citizen vary between countries. In Canada, for example, there are three main differences between a permanent resident and a citizen:

- PRs cannot vote nor run for office.

- PRs they must renew their status as a permanent resident typically every five years.

- PRs can lose their status if convicted of a serious crime.

However, PRs have full access to all other rights and freedoms enjoyed by citizens.

Figure 9-4: A newly-landed Canadian Permanent Resident. Source: https://flic.kr/p/wCpJBK Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Ross.

Foreigners seeking to become permanent residents or citizens of the receiving state do so because of push factors or pull factors:

- Push factors include all of those circumstances that make staying in their home country untenable, for example, natural disasters, war, or persecution for their politics, identity, or sexual orientation.

- Pull factors include all those circumstances that attract people to the receiving states, for example, economic opportunity, greater individual freedom, or family reunion.

Most foreigners entering the receiving country do so through regular migration channels, especially those visiting for a short duration. Regular migration channels are constituted by domestic and international laws, norms, regulations, policies, and traditions. Applying to enter a country through regular migration channels typically involves visiting the destination country’s embassy and applying to visit for either a limited duration or to seek permanent citizenship. Here, the applicant can be advised on visitation rules, permanent residency, or citizenship and make any formal application required, including submitting any necessary documentation. For citizens of some states seeking to enter other specific states for a limited time, this may be unnecessary due to agreements between the sending states and receiving states. For example, citizens of the United Arab Emirates have the world’s most powerful passports, allowing holders to enter 118 states without a visa and to receive a visa on arrival in 60 more. Canadians also hold a powerful passport, allowing holders to enter 116 states without a visa and receive a visa on arrival in 52 more. Compare this to Afghanistan, Iraq, or Syria, which requires their respective passport holders to apply for a visa in advance in 163, 161, and 158 states, respectively (for more information, visit www.passportindex.org).

Figure 9-5: A passport stamp. Source: https://pixabay.com/images/id-1143491/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of jackmac34.

Again, the vast majority of those seeking PR or citizenship to Canada do so through regular migration channels. In 2019, 310,000 immigrants used these channels to settle in Canada. However, some foreigners enter the receiving country through irregular channels and are therefore labelled irregular migrants. It is important to note that it is incorrect to use the term ‘illegal’ migrant for two reasons. First, some people, like asylum seekers or refugees, have a legal right to make an immigration claim but may not go through regular migration channels. Second, even if a migrant breaks the law of the receiving state, they as a person do not become ‘illegal’; rather, we can say their actions are illegal. In 2019, 16,077 irregular migrants entered Canada.

Figure 9-6: “No one is illegal!” sign for May Day of Action. Source: https://flic.kr/p/6jTZJZ Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Tania Liu.

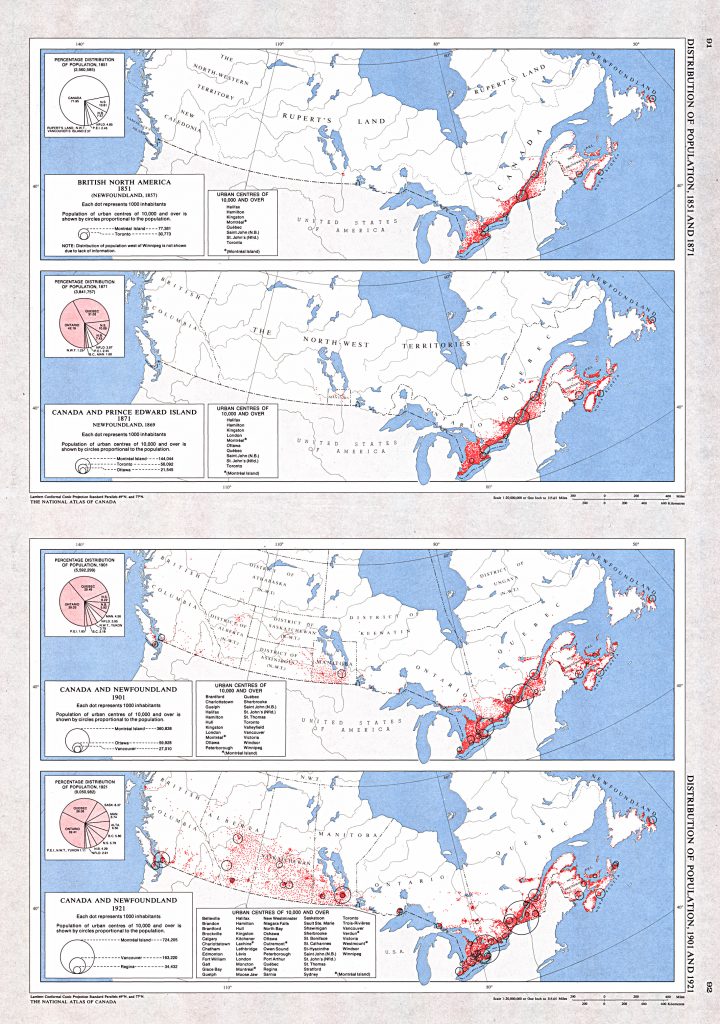

It is also important to note that immigration is one of the oldest human activities, constituted by slow shifts in nomadic patterns and the pull of rising metropoles and sudden shifts due to changes in the environment or invasion by other peoples. Immigration policy, while not as old, does reach as far back in history as organized political units. Ancient China, Rome, Greece, Egypt all had policies to control who could enter their borders and what the rights and responsibilities of these foreigners were. The Ottoman Empire is an interesting example. While being a dominant Muslim empire, Başak Kale (2014) argues the Ottoman’s liberal immigration policies had created a multi-faith and multi-ethnic polity that existed through the 14th to 19th centuries, albeit a bit less tolerant after the failed siege of Vienna in 1639. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Europeans migrated through exploration and imperialism, which turned to outright colonization in the 16th through 19th centuries. However, in general, immigration policy was much less onerous and structured before the 20th century. For example, up to the late 19th century, important contemporary receiving states like Australia, Canada, and the US tended only to bar entry to those who would pose an obvious burden on the state.

Figure 9-7: A collection of four maps showing the distribution of population for 1851 (Newfoundland 1857), 1871 (Newfoundland 1869), 1901 and 1921 by historical region. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canadian_pop_from_1851_to_1921.jpg Permission: CC BY 2.5 Courtesy of Natural Resources Canada – The Atlas of Canada.

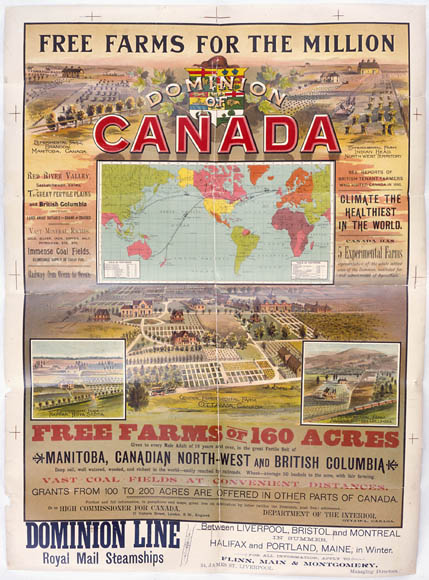

Canadian immigration policy is an instructive example of policy evolution through the 20th century. In the 1880s, open immigration policy began to change as race-based policies were put in place to discourage and limit immigration from Asia, with the ‘Chinese Head Tax’ being a prime example. In 1910, Canadian immigration policy gave the Government the ability to control immigration based on race, occupation, and the potential for assimilation. By the end of World War One, open immigration policies closed in Canada and most other major destination states. After World War Two, several trends emerged in immigration policy in Canada and other major recipient states:

- First, immigration policy became more open as receiving states sought skilled labour to contribute to the post-war economic boom. However, that did not mean that all immigrants were treated as equals. A strong racial hierarchy remained in force, as evidenced by the 1952 Immigration Act, which put the UK, the white Commonwealth states, the US, and France at the top of the immigration priority hierarchy. Next came immigrants from Western, then Southern and Eastern European states. Finally, Asian states were at the bottom of the hierarchy.

- Second, the onset of the Cold War in the 1950s and Canada’s new international orientation shifted Canadian immigration policy towards political considerations. In 1956, with a Ministerial exemption, 37,000 Hungarian refugees were allowed to settle in Canada. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, 100,000 Indochinese refugees (also known as Vietnamese ‘Boat People,’ although that term is no longer in use) resettled in Canada.

- Third, as overt racial screening became untenable in the 1960s and the scope of the welfare state was put squarely on the institutional agenda, immigration policy became defined by the ability of applicants to fill economic needs. This economic focus has led to the adoption of a points-based or merit system for immigration.

- Fourth, in the late 1970s, the idea of humanitarian obligations emerged part in parcel with debates on Canada’s official adoption of multiculturalism and the adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Figure 9-8: Poster advertising free farms for settlers. Source: https://flic.kr/p/WLhApQ Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of BiblioArchives/LibraryArchives.

Taken together, we can see that Canadian immigration policy had been pushed and pulled by four trends: the need for skilled labour, a fear of cultural difference, geopolitical considerations, and the inclusion of humanitarian goals. This means that contemporary immigration policy has remained a contentious policy area that can whipsaw back and forth quite quickly. For example, during the economic recession of the 1980s, the anti-immigration sentiment was common and influential. At the same time, pro-business lobbies were still seeking skilled and, at times, cheaper labour and were, therefore, advocating for more open immigration policies, as were diaspora communities and humanitarian groups. As the economy improved in the mid to late 1990s, these pro-business advocates overcame the anti-immigration voices. The pro-immigration positions were reinforced with the Government’s recognition of the threat posed by declining birth rates and the prospect of an inverted population pyramid. However, the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001 once again empowered the anti-immigration movement; this time, their argument was strengthened by the securitization of foreigners, where non-Canadians, and in particular people living in dominant Muslim countries, were typecast as dangerous and as potential terrorists. Similar debates occurred with the increased number of refugees generated by the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts, and even more so for the refugees flowing out of the Syrian conflict. President Trump’s nationalist and racist rhetoric amplified the anti-immigration voices in Canada and seemed to legitimize their concerns. More recently, President Trump’s anti-immigration and anti-foreigner policies have had a more direct influence on Canadian immigration debates – specifically, undocumented migrants and asylum seekers in the US, fearing deportation or the forcible separation of their families have chosen to become irregular migrants crossing the Canadian border. This has renewed the immigration debate in Canada.

Politically, the American policies have put the Trudeau Government in a contentious position. On the one hand, dealing with the increased number of irregular migrants in a welcoming and humanitarian way has some benefits. First, there are political benefits in capitalizing on the anti-Trump feelings broadly held in Canada. Second, it gives some substance to the Government’s claim on Canada’s liberal international legacy and conforms to the anti-discriminatory framing of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. On the other hand, these irregular migrants are crossing the border illegally because of the Canada-US Safe Third Country Agreement, which closes the regular migration channel for many applicants since migrants are required to request refugee protection in the first safe country they arrive in. The anti-immigration advocates have used the illegality aspect to generate angst among Canadians who see themselves as a country of rule-abiding citizens.

Figure 9-9: RCMP constable at US border telling asylum seekers at the end of Roxham Road in Champlain, NY, that this is not a legal entry into Canada and that they must go east to the Lacolle crossing if they do not want to break Canadian law. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RCMP_telling_asylum_seekers_attempting_to_cross_border_that_they_must_enter_Canada_somewhere_else_since_this_is_not_an_official_entry_point.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Daniel Case.

However, before wrapping up this section on Canadian immigration policy, it is useful to introduce one novel aspect of Canadian immigration policy – the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program (PSR). In response to the Indochinese refugee crisis in the mid to late 1970s and the appetite by Canadians to help, the Canadian Government created the PSR. The PSR stipulates that for every refugee that private citizens sponsor for resettlement in Canada, the Government will publicly sponsor one refugee. Individuals, groups, or organizations can undertake this private sponsorship. Sponsors must provide financial and settlement assistance for at least one year, although the relationship between sponsor and refugee often lasts much longer. This support includes providing the basic requirements of food, shelter, and clothing and emotional support, coaching on how to deal with government policies, registering children for school, finding language support, et cetera. The program has resulted in over 275,000 refugees settling in Canada. From a policy perspective, the program is quite interesting. It facilitates buy-in from Canadian citizens, diversifying criticism from some groups who might oppose increased refugee settlement. Perhaps, more importantly, it is a way for decisionmakers to gauge public interest in accepting refugees. While Canada was the first state to create a PSR policy, Australia, New Zealand, and the Netherlands are working on their own PSR policies and the UK has implemented its version in 2020.

In the end, perhaps Reg Whitaker says it best: “Canada, it would seem, is a country of immigrants that has never quite made up its mind about immigration.”

Figure 9-10: Indochinese Refugees Arriving in Canada, 1978. Source: https://flic.kr/p/U8DefY Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of manhhai.

Watch the following videos:

‘Canada’s Immigration History’ https://youtu.be/zUQn7JTLoME

*This video shows foreign-born immigrants in Canada differentiated by country of origin from 1919 to 2019

CBC – ‘How is Canada’s immigration system different from the US?’ https://youtu.be/sgvqYkd3Vu0

CBC – ‘Poll: Canadians have conflicted views on tolerance and immigration’ https://youtu.be/LoA4V6Z5JGU

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- a. What did you notice in the visualization of Canadian immigration data?

b. How have things changed over time? - a. How is Canada’s immigration system different from the US?

b. What are the strengths and weaknesses of each? - a. How is public opinion divided over immigration?

b. What explains this division? - How do you think this history and these tensions in Canada have, or will, influence Canada’s immigration policy?

Immigration as a Public Policy Issue

Research on Immigration Policy

Research on immigration policy tends to focus on one of two areas. On the one hand, this research may take a case-study approach. A case study approach focuses on how particular states, with particular histories, have created the laws, norms, and processes of policing their borders. These histories are deeply embedded in both domestic politics and those international events that put varying degrees of pressure on a state’s borders. Domestic political debates focus on economic considerations, on how many immigrants should be allowed in, and from which sending states. Internationally, a state may experience increased pressure from a natural disaster, like the Ethiopian famine in the 1980s, or human tragedy, like the ongoing Syrian conflict. Such studies ask specific questions, such as: Why is this identifiable group of people seeking to enter a particular country? What facilitated or obstructed this immigration flow? How well did the immigrants integrate into the country? What are the settlement outcomes? Researchers parse these answers to find causal mechanisms or at least strong correlations, and compare their findings to research in other states. The similarities and differences found between cases can suggest answers to questions about why similar states had different policies or different outcomes; it can also answer questions about why different states had similar policies or similar outcomes; and, it can answer all the possible variations therein. This is an approach we discussed with Mill’s methods of agreement and disagreement.

The other approach starts by looking at the broader processes and definitions of immigration and the larger international context within which migration happens. It looks at the historical background to the legal, political, and institutional form and function of migration and immigration policy. Historically, what patterns emerged in immigration flows? Who was sending, and who was receiving? What international norms and institutions shaped these flows? From this approach, the important questions focus on what defines an immigrant and immigration. What kinds of immigrants are there? – for example, are they economic migrants? Refugees? Asylum seekers? Climate refugees? What are the meaningful differences between them? Are they motivated by push or pull factors? How have the receiving states reacted? What types of policy convergence occur, and between what kinds of states? – for example, what were the requirements to migrate in the late 19th century? Early 20th century? What differences are there between these two time periods? What accounts for these differences? How did significant events and processes impact migration flows, from European colonization and World War One to 9/11 and the Syrian conflict?

Types of Immigration Policy and States

More technically, we can divide immigration policy into two main types: policies that regulate the conditions and numbers by which migrants move across borders (immigration control), and policies that regulate migrants once they arrive (immigration integration). These policies are further divided by the different types of migrants that exist, in terms of who they are, how they arrive, the duration of their stay, and what they will be permitted to do while living in the receiving state. Think of all the different sort of migrants that exist: those seeking permanent residence, citizenship, non-immigrant visas, temporary work visas, asylum and refugees, and those joining family members. This doesn’t even include immigrants that arrive as one type of migrant and then become another – such as entering the country on a temporary work permit, transitioning to permanent residence, then applying to become a citizen.

Figure 9-11: Immigrants on a ship approaching New York City, bound for Ellis Island, with the Statue of Liberty in the background. circa 1915. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Immigrants_Approaching_Statue_of_Liberty.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

We can also divide states into three main types: sending states, transition states, and receiving states. In migration, a sending state would be the country from which a migrant departs, and a receiving state would be the country at which the migrant eventually arrives. There likely will also be states through which a migrant travels but does not intend on settling in – these are transition states. Every state will experience individuals both arriving, transitioning, and leaving. However, what is significant is whether a state is a net receiving or a net sending state, as this will produce different perspectives on immigration.

No state exists today which allows for total, uncontrolled immigration. Each country has its own level of tolerance. Each state must decide how many migrants may enter their state and under what conditions they are allowed to enter. Each state must decide who can become a member of the nation through citizenship, itself a collective construction. As Leitner (1995) argues, this mythology defines who belongs within a country and who does not. Understandably, typical-sending states and typical-receiving states are likely to have different types of mythology regarding nationhood. For example, Citrin and Sides (2008) compare immigrant-settler states like Canada and the United States, with the established states of Europe. There is an accepted truth amongst the citizens of settler states that, aside from Indigenous peoples, the nation is comprised of people whose families at some point were immigrants – that all of “us here” came originally from “over there.” In contrast, most European states tend to define themselves in explicitly ethnic terms, and immigration is most decidedly less part of the construction of national identity.

Figure 9-12: A sign at Pier 21, Halifax. Source: https://flic.kr/p/4BcQDi Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of abdallahh.

Watch the following videos:

‘What’s the Difference Between a Migrant and a Refugee? Migration Explained’ https://youtu.be/vwSOds50Afk

Global News: ‘Poll shows Canadian attitudes on immigration are hardening’ https://youtu.be/FuzIeDTZWKU

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- Describe the current status of global migration.

- a. What is the difference between a refugee, economic migrant, asylum seeker, and internally displaced people?

b. What is the significance of these definitions? - What are some of the pros and cons of immigration?

- a. What are the debates on immigration and refugees in Canada?

b. Why is the language used in immigration debates in Canada important? - What is your opinion on refugees and immigration?

Applying the Frameworks of Comparative Public Policy Analysis

Much like we did in the previous module, we will now turn back to comparative public policy analysis frameworks to make sense of immigration policy. Recall the following frameworks from earlier modules:

- The Policy Cycle

- The roles of Ideas, Interest, and Institutions

- The Multiple Stream Approach (MSA)

- Critical Perspectives

- Comparative Public Policy

Let’s look at each of these more closely.

1. The Policy Cycle

The trajectory and drivers of immigration policy in the policy cycle span both the international and domestic contexts. An essential driver of immigration policy is the necessity of the state to react to international events, specifically crises and international processes that set expectations, norms, and rules on migration. Conversely, domestic attitudes are often determinative of the specific policy responses to migrants and immigration. While certainly not exclusive, the impact of the international context is more influential in the agenda-setting stage. The domestic context is much more prominent in the decision-making stage.

The Agenda-Setting Stage

In the agenda-setting stage, immigration policy is often driven first and foremost by international events and processes. When some form of international crisis happens, there can be a strong ‘push’ factor that results in a surge of migration. For example, the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 created a wave of migration out of Hungary, as did the Ethiopian famine in 1983, the influx of Indochinese refugees in the late 1970s and 1980s after the establishment of communist governments in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, and the Syrian civil conflict in 2011. These migration surges force other states to respond. However, the rationale and type of response vary considerably. The states closest to the affected area often have little choice in responding, and this is often defensive as they seek to manage the crisis. Other, more distant states have more leeway to frame their response.

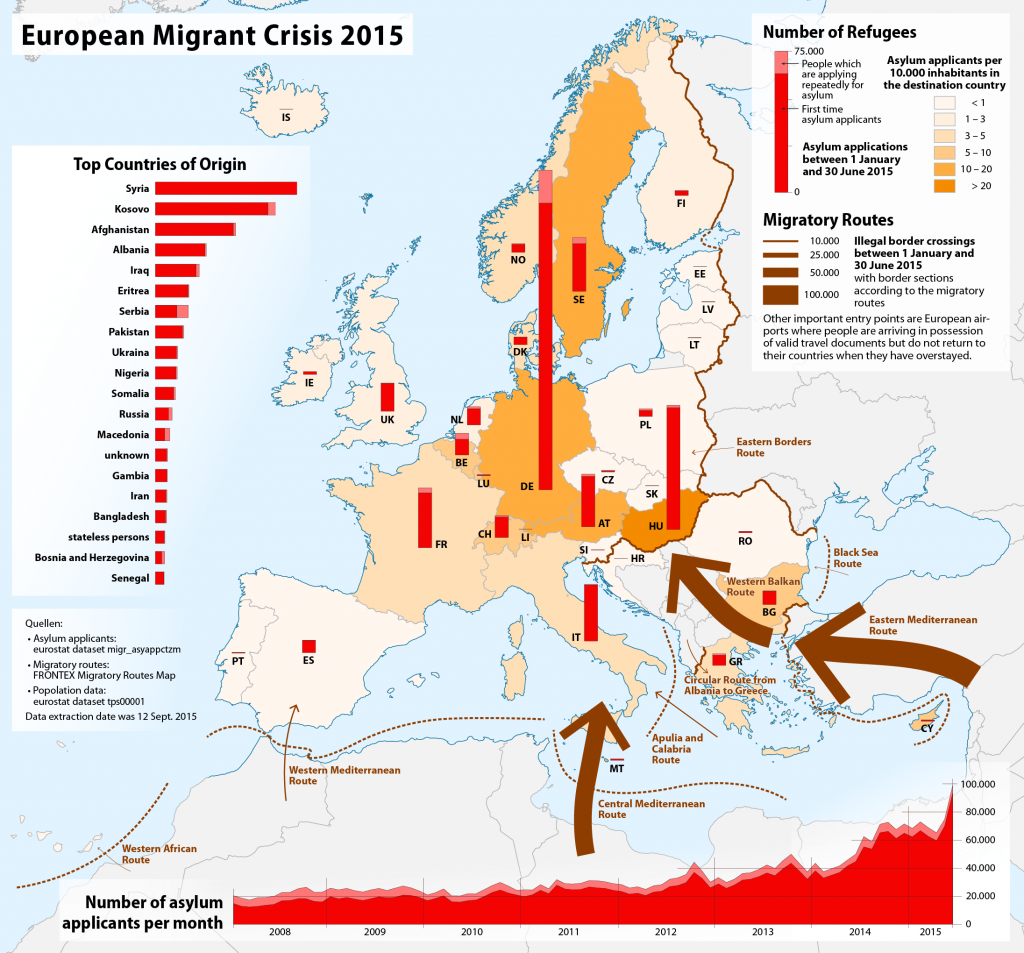

The ongoing Syrian Refugee Crisis is an instructive case. Civil unrest broke out in 2011. In 2012, the UNHCR set up the Zaatari refugee camp in neighbouring Jordan, hosting at its peak 156,000 refugees. By 2013, the UNHCR had registered 1 million refugees with Jordan and Lebanon, taking the brunt of the refugee flow. By 2015, there were 12 million displaced Syrians, 250,000 dead, and 4 million registered refugees. By 2017, more than 5 million people had fled Syria, most through regular migration channels, but an increasing number have become irregular migrants. In 2017, there were 6.3 million internally displaced Syrians, a number that has remained relatively constant for several years, leading to further migratory pressure. Those states neighbouring Syria have become hosts for the vast majority of refugees: Turkey (3.4 million), Lebanon (1 million), Jordan (660,000), Iraq (250 thousand), and Egypt (130,000). Europe is the second-largest destination: Germany (532,000), Sweden (109,000), Austria (49,000), and the Netherlands (32,000). Other significant destination states include Canada (54,000) and the US (33,000). This pattern underscores the point that geographic proximity forces immigration and refugee policy from the systemic agenda to the institutional agenda. More distant states have a greater choice in how, or even if, these crises influence the institutional agenda.

Figure 9-13: The Zaatari Refugee Camp, Jordan. Source: https://flic.kr/p/VCy7hg Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of United Nations Photo.

Beyond push factors, like conflict and disasters, there are pull factors at work in the agenda-setting stage. Globalization’s economic, political, and social processes have created strong incentives for people in less economically developed parts of the world to migrate towards the more advanced economies. This process has only accelerated, especially given the advancements in information and transportation technologies. Information technology has allowed the poorest corners of the world to witness what must seem like obscene levels of wealth in the richest corners of the world. Transportation technology has lowered the cost and access for migration. However, similar to the push factors of migration, proximity plays a role in the pull factors. Proximity explains why the Mexico/US border is such a contentious issue. Mexico has a GDP per capita of 9,700 US$, while the US has a GDP per capita of 63,000 US$. A similar, albeit more complicated, relationship exists between Western Europe and North Africa & the Middle East region, with the former having an average GDP per capita of 57,000 US$ and the latter 8,000 US$. These disparities have resulted in migration pressure on the borders of both the US and Western Europe. However, unlike the more intense and sudden pressure exerted by push factors, pull factors are more sustained and long-term. The slower and more constant pressure of pull factors often frames immigration policy debates. It is a narrative of refugees in desperate need of help, generated from a crisis, that can foster a positive view of migrants and immigration. A narrative of economic and irregular migrants, people who choose to leave their home state, who might break the law of the receiving state, can create a negative view of migrants and immigration. The tension between these positions may also result in apprehension over recognizing immigration as an institutional agenda item. Thus, the Government may prefer to let border control organizations and immigration services handle the issue.

Figure 9-14: A US Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE) truck. Source: https://flic.kr/p/dYAxqi Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Lee Cannon.

The Policy Formulation and Decision-making Stages

At the policy formulation and decision-making (i.e., policy adoption) stages, the international context still plays a role but less so than domestic politics. There is international pressure exerted on policymakers from international NGOs, international organizations, and other states to contribute to resettlement policies in times of crisis. There is also more subtle but consistent pressure being exerted by these same actors to deal with issues of global poverty and inequality as well as the dangers facing the migrants that poverty and inequality generate. However, the influence of domestic actors far outweighs this international pressure in the policy formulation and decision-making stages. On the one side, there are the pro-immigration actors that seek to increase the number of immigrants allowed as well as the number and types of integration services available once they arrive. These include, for example, pro-business groups, humanitarian groups, and diaspora representations. On the other side, anti-immigration groups see migrants and immigration as a threat to their economic well-being, cultural identity, or value systems. The economic climate and proximity to the crisis are often determinative of the balance between these two positions. If the economy is strong, the balance often tips in favour of more immigration versus less immigration. If a proximate crisis creates migration flows, there will be less room to maneuver, forcing a policy response. Moreover, proximity also means there will likely be stronger ties and interest groups involved. In this mix of the economic climate, proximity, pro-immigration and anti-immigration lobbies, as well as international agreements, decisionmakers must craft policy formulations and make policy decisions.

The Syrian refugee crisis is, again, a useful example. For those states most proximate to the crisis, like Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, there is little choice but to formulate and decide on an immigration policy. Not only are they faced with an immediate crisis on their border, but their respective citizens also demand a response. These responses tend to be mixed, for example, by allowing refugee camps to be built but limiting the free movement of those in the camps. Those states further away have more space and time to debate how they should respond to the Syrian refugee crisis. In Germany, which settled the largest number of Syrian refugees outside of the Middle East, the political debate was intense. Chancellor Angela Merkel had the option of not responding since the EU offered a buffer for decision making. Further, there was some political rationale to avoid acting since immigration has been a contentious issue in Germany. On one side, the Government is dealing with the legacy of WWII and has sought to reform its image into a humanitarian and progressive state. Further, supporting a more liberal immigration policy is an ageing population and the need to fill labour gaps. On the other side of the debate, the poor integration of the Turks who settled in Germany through the ‘guest worker’ program in the 1960s and the inequality between former West Germany and East Germany has created a sizeable population hostile towards immigration generally. Chancellor Merkel decided to open Germany to large numbers of refugees, and her party, the Christian Democratic Union, has paid the price. The CDU lost a significant number of seats in the 2017 election, and more far-right and anti-immigration parties like Alternative for Germany gained seats. The Syrian refugee crisis has proven to be a wedge issue in Canada as well, albeit a much less divisive one due to the distance from the conflict and the space for policymaking. These tensions were evident in the debate over immigration and refugee policies in the 2015 and 2019 federal elections and the 2018 Quebec election. These elections have shown that there is a significant anti-immigration constituency but that, on the whole, there is at least a narrow majority that accepts the positive narrative of immigrants and immigration in Canada.

Figure 9-15: Syrian Refugees on the Hungarian Border. Source: https://flic.kr/p/GpjZNb Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Rebecca Harms.

2. The roles of Ideas, Interest, and Institutions

Ideas

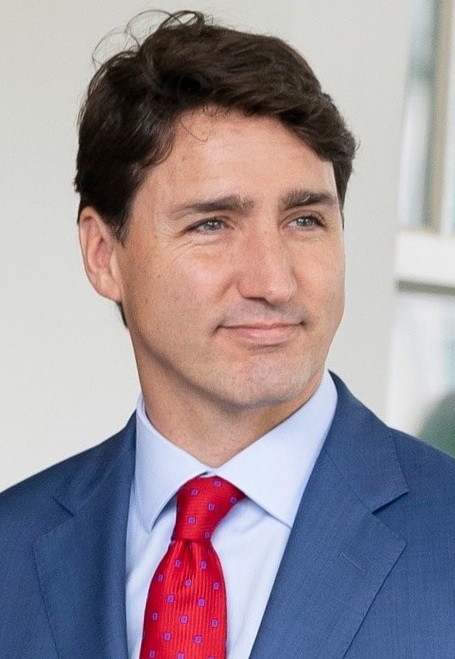

Ideational factors play a substantial role in shaping immigration policies. Immigrants and immigration are not monolithic categories. A refugee is seen differently than an economic migrant, and an immigrant that came through regular migration channels is perceived differently than an irregular migrant. Each of these terms comes with its own narrative. Refugees and asylum seekers are often seen as victims, people who were forced to flee through no fault of their own. They are someone in desperate need of help. An economic migrant, on the other hand, is seen as a person who has made a conscious choice to try to immigrate and who may be bringing specific skills that might compete with citizens in the receiving states. Immigrants who have clawed their way through the regular migration channels are seen as relatively ‘safe,’ having been vetted through the receiving state’s immigration and security services. Irregular migrants are seen as rule-breakers who have ‘skipped the queue’ and may pose a security risk as there is a perception that they have not been fully vetted. Those with a particular agenda will try to frame these narratives for their own gain. For example, in the run-up to the 2015 Canadian election, Conservative MP Kellie Leitch attempted to play on the fear of immigrants when she proposed the tip line for ‘barbaric cultural practices.’ Alternatively, in 2017 PM Justin Trudeau tried to play on anti-American sentiment and pro-immigration constituencies when he tweeted:

To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #WelcomeToCanada

— Justin Trudeau (@JustinTrudeau) January 28, 2017

Both Trudeau and Leitch were seeking to frame immigration for partisan political purposes. This framing speaks to perhaps the most crucial ideational component of immigration policy: public perception.

Figure 9-16: Justin Trudeau visits the White House. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trudeau_visit_White_House_for_USMCA_(cropped)_(rotated).jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of The White House.

For policymakers in receiving states, one of the most important considerations is public perception: is the public favourable to immigration? To what degree? Does it matter where immigrants are coming from? Research in public perception often uses polling to measure public support. However, this polling data comes with an important caveat since the type of questions asked in such polls can vary greatly in terms of bias. For example, a think tank with an anti-immigration disposition may ask, “do you think the recent surge in illegal migration is a threat to Canada?’. This is a loaded question in many regards. It uses terms like ‘surge,’ ‘illegal,’ and ‘threat,’ all of which make immigration sound dangerous. Alternatively, a pro-immigration think-tank may ask, ‘do you think people seeking a better life in Canada, who are willing and able to fill much-needed labour gaps, are a net contributor to Canada’s quality of life?’. This is also a loaded question as it only uses positive terms. A less biased set of questions would disaggregate many of these underlying assumptions. For example, they may ask questions like: “do you think Canada should decrease, maintain, or increase its immigration levels? Should Canada decrease, maintain, or increase its acceptance of refugees? Should Canada decrease, maintain, or increase family reunification? Should Canada use a merit-based system of immigration that scores applicants on their education, language, work experience, age, and whether the applicant already has a job offer?” Beyond polling, research on public perception can also be of a more critical nature, measuring and seeking the basis of racial prejudice, for example. Recently, this critical research has been prominent in the US, seeking to make sense of President Trump’s directives to change Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) policies, especially on family separation.

Figure 9-17: Photo provided by Custom and Border Protection to reporter on tour of detention facility in McAllen, Texas. Reporters were not allowed to take their own photos. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ursula_(detention_center)_2.jpg#/media/File:Ursula_(detention_center)_2.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of US Government – U.S. Customs and Border Control.

According to Ceobanu and Escandell (2010), several ideational factors influence public perception. At an individual level, perception is influenced by identities and values. In other words, perception is influenced by whether the immigrant community has shared historical national roots or religious and/or cultural values. For example, people who have a strong sense of hybrid identity, say French-Canadian, Ukrainian-Canadian, or Japanese-Canadian, would have a more positive feeling towards immigrants from these countries or nearby countries with shared culture or values. Conversely, those with strong nationalist feelings may have a more negative view of immigrants and immigration. However, the predictability of identity and values correlating with a positive perception of immigrants and immigration can be weak. For example, there can be differences between first, second, and subsequent generations of immigrants identifying with the ‘home country.’ There is a lot of variance in the degree of integration and ties with the sending state that can influence this perception. There can also be variance in the role of nationalism in predicting the support of immigrants and immigration. For example, some Canadians take pride in the positive narrative of Canadian immigration policy, including the acceptance of 37,000 Hungarian refugees in 1956, the 60,000 Indochinese refugees in 1979-80, and the 26,000 Syrian refugees in 118 days on 2015. At the same time, other Canadians oppose these same government decisions to accept refugees based on a sense of cultural threat. Tangential to the role of identity and values is contact theory. Contact theory argues that having immigrant friends and acquaintances facilitates positive feelings towards migrants and immigration. However, while there is substantial evidence that substantial interaction correlates with a positive perception of immigrants, it is not necessarily clear what kind of contact is absolutely crucial or merely influential in changing immigrants’ attitudes.

At a societal level, Ceobanu and Escandell (2010) also highlight the role of education in framing the perception of migrants and immigration. Education has been consistently shown to correlate with perceptions of immigrants and immigration in various countries. The higher the level of education an individual has, the less likely they are to express anti-immigrant and anti-immigration attitudes. Some argue this positive correlation is due to the role of education in exposing individuals to a variety of factors that can decrease their hostility to immigrants and immigration. These factors include exposure to different cultures, increased economic security, and higher overall knowledge of others and of global events.

Research into social level indicators of perceptions of migrants and immigration often tries to identify attitude predictors. These broadly fall into four categories: beliefs about the consequences of immigration, beliefs about the size of the immigrant population, where individuals fall upon a left-right ideological spectrum, and degree of attachment to the national or supranational community. What is consistent and rather odd is that there exists a widespread perception overestimating the size of immigrant groups, both in absolute and relative terms to the population. Moreover, those that most overestimate the size of immigrant populations correlates with those who hold negative perceptions of immigrants and immigration on the whole. The left-right ideological scale has generally shown that those who are more consistently right-wing tend to be more opposed to immigration. Increased feelings of nationalism are also associated with negative feelings towards immigration. However, as argued earlier, this direction of correlation can be dependent upon the particular formulation of nationalism that the individual espouses. Conversely, those with more supranational ties tend towards more positive feelings towards immigration. Yet, these indicators are not casual but are more predictive, an important caveat.

Interests

Public perception of immigration may indeed be ideational. Still, the basis of that perception is very often a reflection of whether migration and immigration are believed to be a threat or not. Much like the section above on ideas, Ceobanu and Escandell (2010) identify both individual and social level processes that are rooted in an actor’s rational self-interest. At the individual level, the perception of immigration is very often socioeconomic. Socioeconomic factors have proven to be reasonably consistent in predicting perceptions of immigrants – those individuals who believe their jobs or availability of housing is in active competition with immigrants or immigration tend to have more negative perceptions of either. Whereas those who perceive immigrants or immigration as useful for labour shortages or a means to balance the pressure of declining population trends have a more positive perception of immigrants or immigration. The degree of support or opposition is more pronounced during economic hardship, further supporting the notion that individuals develop these perceptions as a response to their own self-interest.

A correlate to individual self-interest is seen at the societal level through threat theory. This theory argues that competition between groups, whether true or part of a particular narrative, influences the public’s perception of immigrants and immigration. More specifically, threat theory looks at the degree to which the collective interests in the receiving state, be they economic, religious, or cultural, of citizens, are threatened by competition with immigrants. Remember, the crucial question here is public perception – does the public perceive immigrants or immigration as a threat to their interests and identities? Critical variables for threat theory are the size of the immigrant group and the time period of immigration. Large and sudden migration groups are argued to be much more threatening than small groups of diverse immigrant groups arriving over a more extended period of time.

Institutions

Both formal and informal institutions play a pivotal role in shaping immigration policy. Borders and the policies around who may or may not enter a state, the conditions under which a person may cross a border, and the conditions they are allowed to stay are among the most formal and least flexible policy areas. In areas with contested borders or where a threat is perceived, borders can be highly militarized. An excellent example of this is the North Korea-South Korea border area or the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between them. Entering or leaving one area into another is a highly formalized, regulated, and strict undertaking. Any breaking of protocol could result in individual harm or even open conflict. Even crossing a less militarized border, like the US-Mexico border, is still formal – and President Trump is trying to make it more so with his proposed border wall. However, even less contentious borders between Canada and the US are institutionalized, albeit less formally. The Canada-US border is the longest un-militarized border in the world. It has cross-border oddities, including six airports and several buildings that straddle the border. While there are many places a person could walk across the Canada-US border, it is still illegal to do so and could result in arrest, as the irregular migrants crossing the US border into Quebec and Manitoba have discovered.

Figure 9-18: Welcome sign, Canada-US border. Source: https://flic.kr/p/aevn32 Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Cohen.Canada.

Turning to our three institutional approaches of public policy analysis (historical, rational choice, and sociological institutionalism), we can see a strong role of historical institutionalism and sociological institutionalism.

Historical Institutionalism provides a strong lens to explain the trajectory of immigration policy in particular states. One of the most telling institutional constructs to influence immigration policy is its historical contingency: is the state traditionally a sending or receiving state? For example, most European states are far more used to being sending states than receiving states, with the opposite being true for traditional settler states like Canada, the US, and Australia. In traditionally receiving states, generations of citizens identify with immigrant ancestors, accompanying national mythos of immigrants and well-organized pro-immigration interest groups. This sets traditional receiving states apart from traditional sending states. While many countries in the European Union have now shifted from net sending to net receiving states, their different histories create a much different context and political climate when debating immigration policy.

Brubaker (1992) identifies another historically contingent aspect to immigration policy: how one becomes a citizen. He divides states into two main categories, citizenship conferred through jus soli or jus sanguinis. Jus soli (Latin: “right of soil”) refers to citizenship given to those born within the state’s borders. Jus sanguinis (“right of blood”) refers to citizenship given to those born from parents who are already citizens. Taking a state-characteristic-focused approach that linked the citizenship model to the country’s unique history, Brubaker analyzed two cases that were good examples of each type: France and Germany. France was a country that had territory, but not necessarily a common people inhabiting that territory. In response to this, France adopted a jus soli approach, combining the development of public education with military service to create the concept of a French nation. Contrary to this, Germany took a jus sanguinis approach since it had the opposite problem of France: a defined nation of people but spread across different territories.

While these historical contingencies have created path dependencies in immigration policies, it is also important to note the critical junctures that have led to institutional change. For example, a number of states have changed from jus soli to jus sanguinis or vice versa due to changing circumstances. Bertocchi and Strozzi (2006) found that states responded similarly to several factors, such as increasing levels of migration pushing jus sanguinis countries to move towards jus soli citizenship. Conversely, a lack of change in the demographics of a state tended to lead to a mix of jus soli and jus sanguinis citizenship. While states that were jus sanguinis were resistant to adopting different citizenship definitions, an increased level of democracy within the country also promoted the adoption of jus soli citizenship standards. For example, in 1986, Australia adapted its citizenship policies from jus soli, to either requiring at least one parent to be an Australian citizen or that the child resides in Australia until 10 years of age before becoming an Australian citizen. In 1993, France adopted a similar citizenship policy, whereby French-born children of non-French citizens have to request citizenship at the age of majority.

It is also important to look for critical junctures that shift path dependencies in the history of immigration policies of particular states. Take the history of Canadian immigration policy, for example. The need to ‘settle’ the prairies led to the immigration policies of Sir Clifford Sifton, who removed the bureaucratic red-tape and added incentives for immigration from primarily eastern and southern Europe in 1896. This created a critical juncture in Canadian immigration policy that would forever change the identity of the prairies. Another critical juncture that set Canadian immigration policy on a different path was World War Two. This was important for several reasons. First, the need for labour began reversing the restrictive immigration policy put in place in the early 20th century. While there was still a hierarchical and racist element to the changed immigration policy, the path would eventually lead to a more open and inclusive policy. Second, the war changed Canada’s foreign policy orientation. The period between 1945 and the 1960s was the height of Canadian internationalism. In terms of immigration policy, this would be reflected in the decision to facilitate mass immigration of Hungarian refugees fleeing the 1956 Soviet invasion. This decision, in turn, would further shift Canadian immigration policy towards inclusivity. Notably, the racist policies against people of colour, and in particular Asians, that had existed since Confederation were finally dismantled in 1962. By 1971, most immigrants were non-European, and in 1979 Canada facilitated the large-scale immigration of Indochinese refugees.

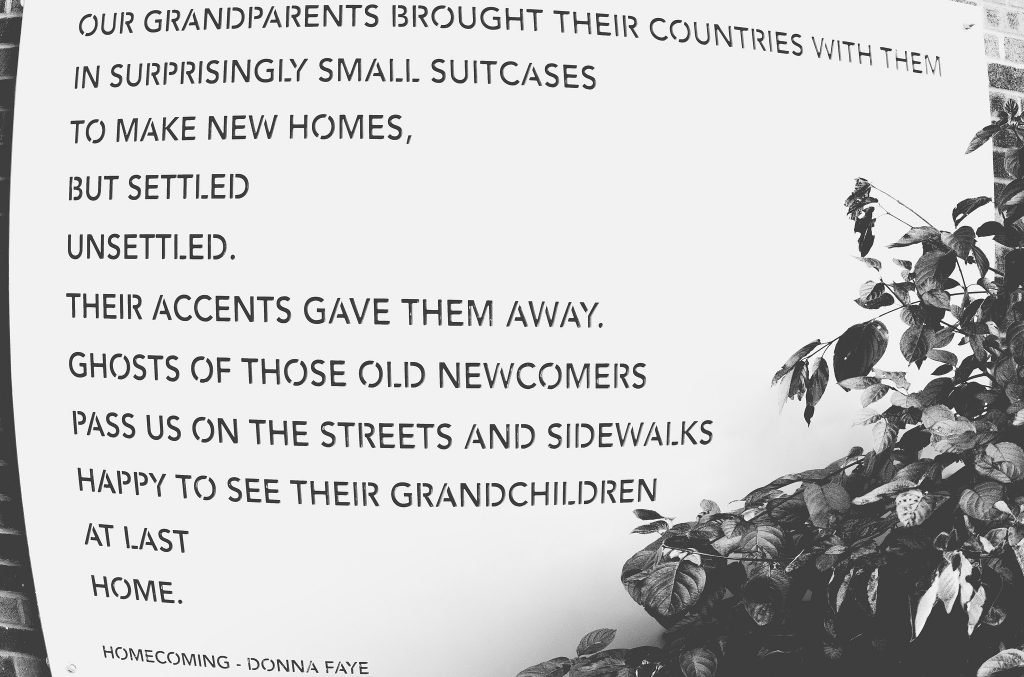

Figure 9-19: Poetry at Marina Park, Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada. Source: https://flic.kr/p/z1Luhx Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Tony Webster.

Rational Choice Institutionalism best explains means to overcome collective action problems and reduce transaction costs by binding actors with structural constraints. The European Union is a good case study of rational choice institutionalism in immigration policy, albeit exposing as many weaknesses as advantages to the EU. When European states were confronted with many Syrian refugees in 2015, there was an incentive for individual states to deny entry for fear of becoming overburdened. This was particularly true for the frontline states of Greece, Italy, Spain, and later Hungary. And there are certainly cases of these states denying entry of refugees and irregular migrants, even cases that may have contravened international law and EU regulations/directives. Regrettably, this has come with a price of many refugees dying in the process of trying to reach Europe. But EU Member States have been under intense pressure to conform to the structural norms, rules, and procedures established by the EU on immigration and refugee policy. Notably, the front-line states have been encouraged to adhere to the rules of refugee claims, and the EU institutions have supplied resources, both monetary and personnel, to help process these claims. They also signed an agreement with Turkey to stem the surge in refugees seeking entry into Greece. The non-frontline states have been encouraged to share the burden of settling such a large number of refugees, and some, like Germany and Sweden, did settle a significant number of Syrian refugees. However, despite the EU institutions seeking to apply structures, incentives, and burden sharing, many states have not fully complied due to domestic political opposition, most notably Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic, and Slovakia. From this example, we can see the role of rational choice institutionalism in shaping, or at least potentially shaping, immigration policy.

Figure 9-20: European migrant crisis. Asylum applicants in Europe between 1 January and 30 June 2015. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_the_European_Migrant_Crisis_2015.png#/media/File:Map_of_the_European_Migrant_Crisis_2015.png Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Maximilian Dörrbecker (Chumwa).

Sociological Institutionalism also comes to bear on immigration policy, domestically and internationally. Sociological institutionalism questions the consequentialist logic of rational choice theories and instead posits a logic of appropriateness. Domestically, we can see this at work in immigration policy. For example, take Canadian immigration policy. The meaning of immigration to Canadian decisionmakers and the Canadian public writ large has evolved. This changing meaning of immigration, in turn, has shaped what the citizens expect of the state in formulating and implementing policy. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, immigration was a means to settle the West, especially the prairies. The Government was expected to recruit suitable immigrants, like farmers, to do so. Post-World War Two, as Canada embraced a more liberal international role, there was an expectation that Canada would contribute to solving crises like the Hungarian refugee crisis or the Indochinese refugee crisis. In each case, the shift in policy can plausibly be explained by a logic of appropriateness. The EU is perhaps the most far-reaching example of sociological institutionalism. The centralization of competencies in Brussels has led to a changing, and at times conflicted, expectations about which level of Government acts on what issues. Security, which is a core aspect of immigration and border policy, is traditionally a state prerogative. The EU has encroached on some of these prerogatives, though not completely and not without pushback. This has led to confusion about what is expected of whom. However, when things become difficult, as during the Syrian refugee crisis, citizens expect their national Government to defend their interests. Internationally, we can also see sociological processes at work, with the UN’s 2018 Global Compact on Migration being a prime example. International organizations like the UN have sought to build norms, rules, and procedures to deal with global issues, including migration. The Global Compact on Migration is a non-binding agreement that seeks to manage the reality of mass global migration. It affirms migrants are party to the same universal human rights and freedoms as all human beings. It seeks cooperation on data collection and sharing to facilitate migration policy better. In the end, it is seeking to establish a normative framework, albeit a non-binding one, on what immigration policy should look like. However, much like the tension found in the EU, there is significant friction with those who look to the state to protect their particular rights over the more universal ideas of rights and freedoms.

Figure 9-21: The Global Compact for Migration. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PR_Logo_GCM.png#/media/File:PR_Logo_GCM.png Permission: Public Domain.

3. The Multiple Streams Approach (MSA)

In the Multiple Streams Approach (MSA) we are looking for how, when, and why policy windows open, or might open, on immigration policy. A policy window opens when there is alignment between a policy problem, a viable policy response, and political will. In terms of immigration, policy windows tend to open in a crisis. For example, the Syrian refugee crisis forced a policy response, first from neighbouring states, then destination states like Germany, and finally, more distant states like Canada and the US. In times of crises, and in particular, for proximate states, the policy response is often more defensive while still trying to uphold humanitarian obligations, even if only at times in principle. Take, for example, the refugee camps set up in Jordan and Lebanon to house the Syrian refugees with the support of the UNHCR. These camps meet the humanitarian obligation to provide protection, but they can become intergenerational places of limbo. The Zaatari Camp in Jordan was created in 2012 to house 35,000 people and peaked at 156,000 people in 2013. Such camps risk becoming near-permanent intergenerational prisons, like Cooper’s Camp in West Bengal that has existed since the 1947 partition of India or Dadaab camp in eastern Kenya, which has existed for 20 years and, at its peak, housed 500,000 mostly Somali refugees. For more distant states like Canada and the US, there is far more room for policy deliberation. For example, the US has securitized Syrian refugees under the Trump presidency, virtually slamming the door on settlement. Canada, on the other hand, settled over 25,000 Syrian refugees in a little over a year. In each case, a policy window opened, but the resulting policy was vastly different. In the US, President Trump chose an anti-immigration stance as the most politically judicious path, and PM Trudeau chose a pro-immigration policy for the same reason. Both for those proximate states, like Jordan, and the more distant states like Canada and the US, a key variable in understanding their respective immigration policies, is political will. In each case, the demands of citizens and interest groups influence the decisionmaker’s will to act and the subsequent form and function of the policy that emerges.

More generally, applying the MSA to immigration policy requires looking at the policy advocates and entrepreneurs seeking to facilitate or obstruct immigration. The pro-immigration groups include business groups, interest groups, diaspora groups, humanitarian groups, et cetera. Conversely, there are interest groups, often classified as nationalist groups, that oppose immigration. Each group seeks to influence public opinion and have policy options available when a policy window opens, often due to a crisis. Therefore, when PM Trudeau tweeted #WelcometoCanada, each side mobilized to influence the public as they did when irregular migrants began to cross over in greater numbers from the US. The MSA provides a means to assess how, when, and why a policy window might open and what might emerge, if anything, in terms of policy.

Figure 9-22: Policy advocates and entrepreneurs seek to facilitate or obstruct immigration. Source: https://pixabay.com/photos/team-feedback-confirming-office-2894828/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

4. Critical Perspectives

From a critical theory perspective, immigration is a contentious issue. Some argue for more immigration to offset the harm created by global capitalism based on a cosmopolitan approach to human rights. It is posited that the economically developed states are using less economically developed states in a neo-colonial arrangement to extract resources, acquire cheap labour, and as a market to sell its value-added goods. Immigration advocates from this perspective seek to open immigration policy, ease the restrictions on gaining citizenship, and for the state to bolster services for immigrant integration. Others, especially some Marxists, tend to frame migrant labour as an attempt by capitalists to reduce the bargaining power of domestic workers by increasing the supply and therefore decreasing demand for labour. Therefore, it is argued that a more open immigration policy is never actually about migrants but rather about the interests of capitalists in driving down labour costs, undermining unions, and maximizing profit.

In either case, a critical perspective examines the role of power, privilege, and coercion in immigration policy. For example, while PM Trudeau’s goal of resettling 25,000 Syrian refugees is, on the surface, quite laudable, it loses some of its lustre when you assess the degree to which the settlement services and Government more generally were able to support this number of refugees. Likewise, while some in the US may applaud President Trump’s tougher border controls or reduced refugee resettlement on security or economic grounds, the selective and ineffective nature of the policies suggests this was more about catering to his political base.

Figure 9-23: Protesters demanding rights for immigrant workers. Source: https://flic.kr/p/6jYeUS Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Tania Liu..

5. Comparative Public Policy

What would a comparative research program on immigration policy look like? There are a number of fruitful avenues to be explored, depending on what you are seeking to understand. Three common examples of comparative research on immigration policy include labour economics, immigrant integration, and public perception.

Labour economics and immigration policy intersect on the formal or informal provision of labour. A comparative study may look at how Canada’s temporary foreign worker program compares to the irregular migration in the US used for many jobs. Which provides a more stable labour supply? Which provides a cheaper labour supply? Alternatively, a labour economics research project could compare immigration systems to see which has best met the labour needs of the respective state. This could be a comparison of similar systems, like the merit or point-based system in Canada versus that used in Australia or the UK. Or it could be compared to the US immigration system, which privileges family reunification. Research in Canada could compare the differences between the Provincial Nominee Programs that allow each province to attract skilled workers that fit their particular labour needs.

Comparative public policy research into integration is also a prominent area of research in immigration policy. Integration is a reciprocal process. On the one hand, it concerns the processes and outcomes of state policies that facilitate immigrants in adjusting to their new society. On the other hand, it also involves the degree to which immigrants are able and/or willing to adapt to the host society and the choices they make to do so. Integration research assesses the degree of social inclusion and social cohesion. It measures the ability of immigrants to gain employment, access education, access health care, and participate in civic life. In general, this research seeks to assess how well an immigrant, or an immigrant community, has adjusted to the host state or even flourished. This research can focus on ‘newcomers,’ or include more longitudinal studies that assess multiple generations. An example of a comparative public policy research program on integration policy might look at settlement services and integration outcomes across units. This could be between provinces, say Saskatchewan and Alberta, or across countries, say Canada versus Australia. The goal is to identify the similarities and differences that have led to better or worse integration outcomes.

We introduced the importance of public perception on immigration policy earlier in the module. Essentially, this research program is looking at how the public perceives migrants and immigration, how this perception changes over time, and why it changes. Comparative public policy research into public perception most often looks at longitudinal studies. In other words, they measure public perception of migrants and immigration over time. Researchers juxtapose these data points and seek to understand the degree to which perceptions have changed and why they have changed. For example, researchers might note that comparing Ipsos polls between 2017 and 2018, there was an 8-point increase in the number of Canadians who believe that there are too many immigrants in Canada. If there is no clear answer, a new opinion poll could focus on this issue. Alternatively, a comparative public policy research program might look into how migrants, immigration, or particular immigrant groups are perceived across different units. For example, researchers might note a significantly higher level of distrust of Muslims in Quebec than in BC. They then may seek to understand the reason for this through more polling or historical research.

If you haven’t already, read the following articles:

Anne Gallagher: “We need to talk about integration after migration” https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/10/we-need-to-talk-about-integration-after-migration/

Sergi Pardos-Prado: “What’s the best way to integrate immigrants” https://theconversation.com/whats-the-best-way-to-integrate-immigrants-reward-effort-and-dont-make-their-lives-difficult-83679

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Learning Journal:

- What defines integration and integration policies?

- What are best practices in integration policies?

- Using the material from the readings, propose a comparative analysis research project of integration policies using the Ideas, Interests, and Institutions framework.

Conclusion

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the concept of immigration as a public policy issue. We looked at what defines immigration, migrants, and the context of immigration policy. We introduced important definitions like citizenship vs permanent resident and the differences between a refugee, asylum seeker, economic migrant, and irregular migrant. We discussed the role of push and pull factors in motivating migration both historically and contemporarily. We noted the important role that public perception plays in the processes of immigration public policy decision making. Building on this, we introduced different ways to understand how these perceptions are shaped, including the role of proximity, the role of contact, and the role of threat. We suggested that self-interest is an important variable here. The role of institutions was discussed, especially the roles of historical contingency and critical junctures in shaping the expectations of immigration policy both domestically and internationally. We suggested that to understand how immigration policy might change, it is crucial to look to the policy entrepreneurs and advocates that are trying to open policy windows and shift policies once they do. Finally, we introduced a more critical look at immigration policy that asks questions of power, privilege, and coercion.

Review Questions and Answers

Push factors include all of those circumstances that make staying in their home country untenable, for example, natural disasters, war, or persecution for their politics, identity, or sexual orientation. Pull factors include all those circumstances that attract people to the receiving states, for example, economic opportunity, greater individual freedom, or family reunion. The conceptualization of Push and Pull factors are important to understanding immigration policy since they explain the motivation for people to migrate. This in turn influences the public perception of different types of migrants, and these perceptions are deeply influential on the framing and resultant narratives deployed in immigration debates.

The Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program is a novel aspect of Canadian immigration policy. In response to the Indochinese Refugee crisis in the mid to late 1970s and the appetite by Canadians to help, the Canadian Government created the PSR. The PSR stipulates that for every refugee that private citizens sponsor for resettlement in Canada, the Government will publicly sponsor one refugee. Individuals, groups, or organizations can undertake this private sponsorship. Sponsors must provide financial and settlement assistance for at least one year, although the relationship between sponsor and refugee often lasts much longer. This support includes not only providing the basic requirements of food, shelter, and clothing but also emotional support, coaching on how to deal with government policies, registering children for school, finding language support, et cetera. The program has resulted in over 275,000 refugees settling in Canada. From a policy perspective, the program is quite interesting. It facilitates buy-in from Canadian citizens, diversifying criticism from some groups who might oppose increased refugee settlement.

Contact theory argues that having immigrant friends and acquaintances facilitates positive feelings towards migrants and immigration. Threat theory argues that competition between groups, whether it be true or part of a particular narrative, influence the public’s perception of immigrants and immigration. More specifically, threat theory looks at the degree to which the collective interests in the receiving state, be they economic, religious, or cultural, of citizens, are threatened by competition with immigrants. These two theories seem to stand in stark contrast. However, it is possible that prolonged contact may reduce perceptions of threat. And it is also possible that the degree of threat or suddenness of threat may undermine the benefits of contact theory. In both cases, there are highly subjective elements at work that need to be assessed on a case by case basis.

For policymakers in receiving states, one of the most important considerations in deciding on immigration policy is public perception. Since immigration policy can be highly divisive and is dealing with groups to which decisionmakers have no direct obligation towards, the attitude of the general public can be quite influential. Research in public perception often uses polling to measure public support. However, this polling data comes with an important caveat since the type of questions asked in such polls can vary greatly in terms of bias. Beyond polling, research on public perception can also be of a more critical nature, measuring and seeking the basis of racial prejudice, for example.

Self-interest as a variable in immigration policy operates at the individual level, the societal level, and the institutional level. At the individual level, immigration has a socioeconomic aspect. Socioeconomic factors have proven to be reasonably consistent in predicting perceptions of immigrants – those individuals who believe their jobs or availability of housing is in active competition with immigrants or immigration tend to have more negative perceptions of either. Whereas those who perceive immigrants or immigration as useful for labour shortages or a means to balance the pressure of declining population trends, have a more positive perception of immigrants or immigration. The degree of support or opposition is more pronounced during times of economic hardship, further supporting the notion that individuals develop these perceptions as a response to their own self-interest.

At the societal level, self-interest is seen in threat theory which argues that competition between groups, whether it be true or part of a particular narrative, influence the public’s perception of immigrants and immigration. More specifically, threat theory looks at the degree to which the collective interests in the receiving state, be they economic, religious, or cultural, of citizens, are threatened by competition with immigrants. Remember, the crucial question here is public perception. Does the public perceive immigrants or immigration as a threat to their interests and identities? Critical variables for threat theory are the size of the immigrant group and the time period of immigration. Large and sudden migration groups are argued to be much more threatening than small groups of diverse immigrant groups arriving over a more extended period of time.