The film, The Purity Myth: The Virginity Movement’s War Against Women discusses how the virginity movement and virginity discourse shapes people’s experiences and feelings about their sexuality, including if they are even allowed to express their sexuality. This is especially true for young women as the purity myth works to uphold the patriarchy and keep women’s bodies under the control of men.

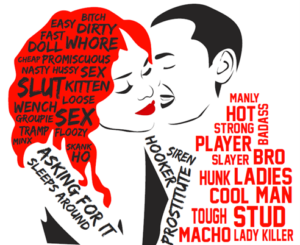

In the film, Jessica Valenti discusses how for those in the virginity movement, and consequently many in wider society, a woman’s worth and character is determined by whether or not she has sex. In this way, women are being reduced to their bodies and sexualities, and “virginity [becomes] the ultimate measure of a woman’s character” (Valenti 9:02). However, as the film states, there remains a double standard between men and women as men’s sexuality is not the primary determinant of who they are. Men are generally celebrated for having sex and this can be seen widely in popular culture, especially in media. As Valenti says, “boys and men aren’t considered less whole when they lose their virginity. They’re not considered damaged goods. And they’re certainly not considered marked for life by this one singe act in the way that women are” (6:57-7:05). In this way, there remains a double standard as men are allowed to express their sexuality and taught that it is good to do so while women are shamed for sexual activities and taught that they are “less than” if they do not remain “pure.”

Additionally, Valenti states that many in the virginity movement see virginity and abstinence as a cure for the over-sexualization and objectification of women in the media. Ironically, the movement itself objectifies and sexualizes women and girls by reducing women to their bodies and upholding the “virgin ideal” (5:05). The “virgin ideal” emerges as the ideal or most desirable woman who “epitomizes the feminine ideal” (5: 26). This woman is innocent and pure and conforms to dominant beauty standards and therefore the male gaze. This includes the woman being “young, white, and skinny” (5:33) as dominant beauty standards remain Eurocentric, racist, fatphobic, and ageist. This ideal teaches young women that they must not only remain “pure,” but conform to this image of the ideal woman to be desirable.

In addition to the discrimination of the “virgin ideal,” the concept of virginity and the virginity movement is heteronormative and cisnormative (McKelle). It assumes that heterosexual sex between a cisgender man and woman is the only valid form of sex. This reinforces the general heteronormativity of society and teaches queer and trans individuals that their sexuality and experiences are not valid or “right” and therefore these individuals are marginalized. As McKelle says, “by forcing sexuality to exist in this small, heteronormative, cissexist, heterosexist box, they can effectively erase the experiences of all people that don’t fit inside of that.”

Furthermore, by demonizing women and their sexualities, the virginity movement is also placing the blame of the objectification of women onto women themselves. There is no regard to the patriarchal and capitalistic ideals that maintain this objectification in media because the movement itself upholds these same harmful values. As Valenti says, purity is “about reinforcing traditional gender roles and restoring the old gender order” (18:56-58). Proponents of the virginity movement oppose feminism and try to reinforce the patriarchal idea that women are, and should be, submissive to men. Moreover, as stated in McKelle’s article, “virginity is a social construction that came about because of the commodification of women.” By objectifying women and treating them as property, the purity myth teaches young women the age-old patriarchal view that their bodies are meant for men.

This patriarchal view that men can and should control women and their bodies is evident in the various methods of the movement. Firstly, the film discusses the phenomena of purity balls where daughters pledge virginity to their fathers and fathers pledge to protect their daughters’ purity. This “pseudo-incestuous” (Valenti 27:57) event which involves a formal dance and the vow of abstinence promotes purity while simultaneously infantilizing and sexualizing young girls by focusing on their virginity (Valenti). In general, purity balls involve men choosing when to “allow” their daughters to have sex (after marriage), thereby reinforcing and teaching their daughters the “antiquated notion that fathers own their daughters and their daughters’ sexuality” (28:08-10). Overall, fathers are exercising their power by taking away their daughters’ own choices about their bodies and teaching them that their sexuality is not their own and their experiences of sexuality need to be limited to what their fathers say it must be.

Another example that the virginity movement uses to maintain “purity” is abstinence-only education which uses intimidation and fear-tactics to teach young people, especially women, to fear sexuality. Even though abstinence education is proven to be ineffective and a public health failure, it is still used in many schools and spreads sometimes straight-up lies about the supposed dangers and immorality of pre-marital sex to promote their patriarchal agenda of “purity” (Valenti).

This harmful messaging done in schools, a major site of children’s socialization, causes the internalization of these ideas and feelings of shame and fear around sexuality. Subsequently, this shapes young people’s views and experiences of their own sexuality and that of others. In turn, they learn to police their own and other peoples’ experiences of sexuality. If people, specifically women, do not conform to the idea of “purity,” there is often “hell to pay” (25:04), and social consequences, such as slut-shaming, work to control and restrain women’s experiences of sexuality (McKelle).

In conclusion, it is evident through The Purity Myth film that virginity discourse and the virginity movement work to shape people’s different experiences of sexuality while reinforcing the patriarchal view that women are inferior and should be submissive to men. Society must rethink the concept of virginity and the value that is placed upon it in determining a woman’s character as Valenti states, “women are more than the sum of our sexual parts and that our ability to be good people has to do with our kindness, our compassion, and our social engagement, not our bodies” (44:24-31).

Works Cited

McKelle, Erin. “5 Reasons Why We Need to Ditch the Concept of Virginity for Good.” Everyday Feminism, 23 Aug. 2013, https://everydayfeminism.com/2013/08/losing-virginity-for-good/.

The Purity Myth: The Virginity Movement’s War Against Women. Directed by Jason Young, Jeremy Earp, Jessica Valenti, and Sut Jhally, Media Education Foundation, 2011. Kanopy.

Attributions

Image 1 : https://bullandbearmcgill.com/dont-you-dare-call-me-a-prude/

Image 5: https://twitter.com/gbvnet/status/1288685750742069250?lang=ca