I was first introduced to coding in high school through a computer science 20 class. In this remarkably in-depth class, we learned everything from how to use Scratch to make basic games, all the way up to some introductions to python. This class while not my least favourite in high school (that was an honour reserved, as with many history majors, for math) was definitely in the running. This was not because it wasn’t valuable, as the courses worth was visible in each piece of technology around us, but rather because it seemed to have nothing to do with what I was actually interested in, history. From this experience I believe I developed a sort of binary in my mind in regards to coding, with it falling squarely on the side of things that those numbers and science people dealt with.

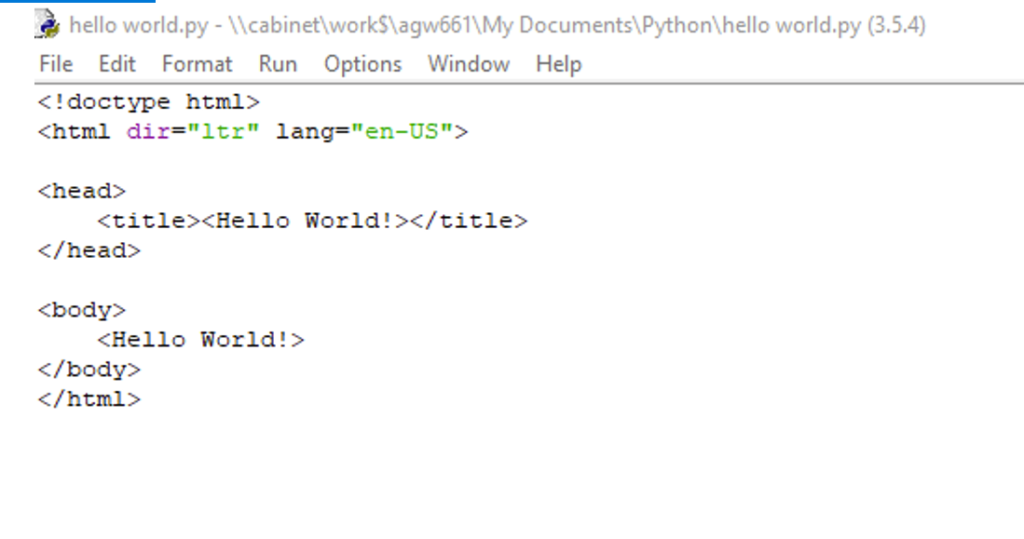

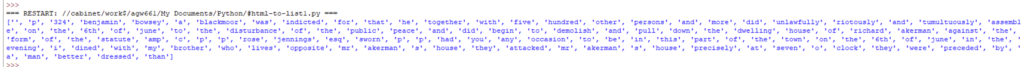

To return to programming after this experience then was not exactly something I was looking forward to then. What had changed this time was the context in which it was presented. Rather than being shown as an end unto itself to accomplish vague tasks it was concretely linked to something that mattered to me the practice of history. This presentation moved away from the more theoretical tasks I had encountered in my high school class to something that could genuinely help my work. I put much of this down to the programming historian tutorials, which while in depth and technical at points, never lost sight of how coding as a tool could help a historian. For example, the idea of using code to scrap html for text was fascinating, and something that not only employed historical examples in the tutorial, but also had a clear application within a historical setting.

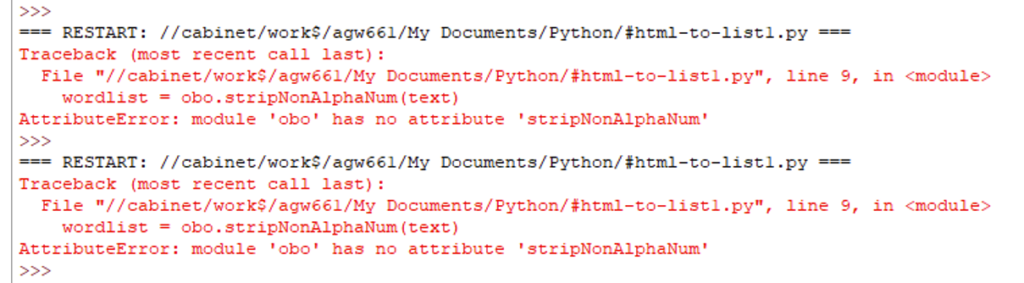

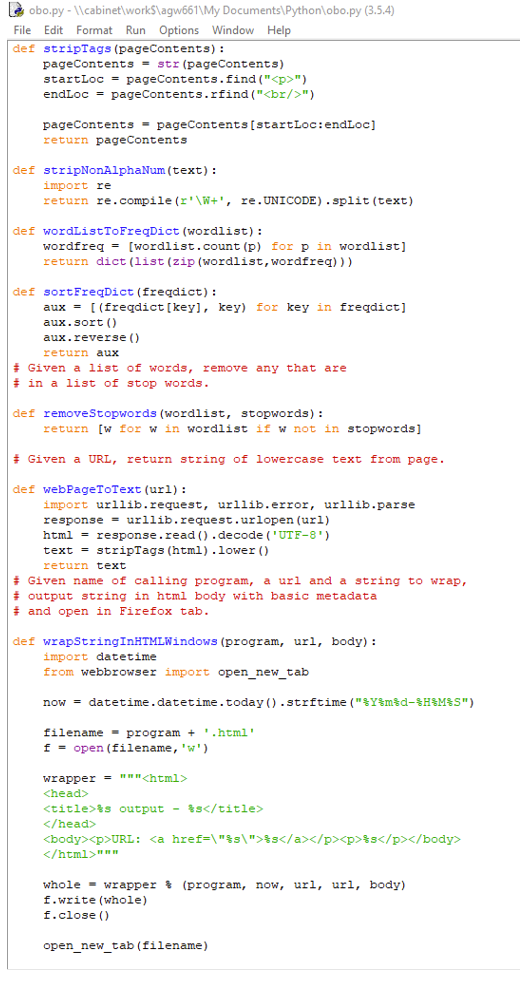

This is not to say that even these relatively clear tutorials had no issues, as everyone with little coding experience in the class encountered a plethora of errors from the major to the minor. This however is to be expected when learning anything for the first time, and overall, it seems we made a decent amount of progress overall.

Despite this progress most of the benefits of coding still seem a long way off from where my skills are now. I would be incredibly hesitant to attempt even simple code within projects contained by the timeframes of university undergrad courses. This is not to say that I didn’t get anything out of the course. Where I found it most useful was in illustrating what kinds of things are possible with code for history. In particular the automation of repetitive tasks on badly designed websites, which I believe at some point or another we have all come across. In addition, I think most importantly it gave me a better chance of conveying my needs of code to someone who has the actual skills to put code together to do a specific task.

I truly believe that coding will only grow in importance as a tool for the historian as more and more text is available in improved OCR. What I think the biggest hurdle this task will face however is in its potential users and in user experience. History generally speaking attracts those that are interested in the humanities and while there is some cross over in interest in other subjects, I think this will be a difficult group to get to buy into the value of coding as a historical tool. Much of this however I believe could be countered with a more simplified user experience from coding languages and systems. While I understand that python is supposed to be one of the easier languages to learn it continues to be far less user friendly than any of the other tools we have explored in this course. If this were to change I believe that buy in would be much higher, but seeing as humanities users make up a relatively tiny slice of their consumer base I doubt that private industry has the desire to pursue this at this point in time.