Megan F.

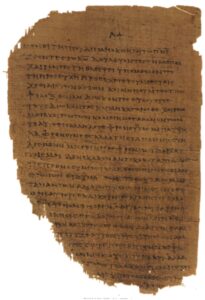

Cipher Manuscript, Folio 1r, courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University Library

A medieval codex with an unknown author and an indecipherable language and script – where did the Voynich Manuscript come from and what does it mean?

Imagine this: you’re rifling through a box of unidentified documents – flipping past loose pages of sermons, financial records, and personal diaries. Suddenly, your hand rests on a thickly-bound codex. You pull it out of the box and run your hands over it, smoothing the centuries-old parchment with your fingertips. Opening it to reveal its pages, you see elegant but unrecognizable writing surrounded by colourful yet rudimentary illuminations. You don’t know it yet, but you’re holding what will soon become known as “The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World” (Hurych).

What is it?

Held at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library since 1969, the Voynich Manuscript (VM) remains one of the world’s most mysterious texts. It is officially named the Cipher Manuscript by Yale, and is classified under the shelf-mark “Beinecke MS 408” (Cipher Manuscript); however its more popular name refers to the rare book trader Wilfrid Voynich who discovered the manuscript in 1912 among miscellaneous texts sold by the Jesuit College of Villa Frascati, just outside of Rome (Hurych). Upon discovering the manuscript, Voynich began seriously studying it and launched what would become more than a century’s worth of public fascination with the enigmatic text (Hurych). Despite decades of research and several compelling discoveries from academics worldwide – including this 2018 study from the University of Alberta – no one has been able to definitively answer the fundamental questions regarding the manuscript:

- Who wrote it?

- What does it say?

- What was its purpose?