Overview

In our last module, we saw the birth and the extension of the modern state system from the Peace of Westphalia to the world. Before that, we examined economic globalization. In this module we will be looking at cultural globalization which is intimately connected to the past two modules. For some, cultural globalization is the vessel within which the particular forms of economic and political globalization occurred; that this was a Eurocentric form of globalization, or born and spread via force and imposition. Others see cultural globalization as a contested space, where there is an ebb and flow of cultural tension that could even lead to war. Still others see cultural globalization as a process of hybridization: that the mix of culture and globalization leads to cross pollination across time and place. It is important to engage with these questions surrounding cultural globalization. If the first position is right, that cultural globalization is a form of homogenization, then the other processes of economic and political globalization are highly problematic. That does not mean the values embedded in contemporary economic and political globalization are without value; a debate on these values is a separate but important topic. Rather, that the process of globalization reflects the values and norms of one particular part of the world. If the second position is right, that cultural globalization is a contested space that could lead to conflict, the implications are very different. It would mean that the national and ideological borders that had defined the Cold War are shifting to new borders defined by cultural clashes. If the last position is right, that cultural globalization is a process of intercultural exchange, the world is a more complex place. Such exchange may be driven by colonialism, migration, technological advances, and economic integration to name a few. That does not exclude the role of power, particularly when culture is exported via colonialism and imperialism. But it does argue that culture is resilient and is malleable, that the cultural world is multi-polar, with different cultural forms and actors having differing influence in different parts of the world. In a sense, engaging in the questions of cultural globalization informs how we understand the narrative of globalization.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Distinguish between the three positions of cultural globalization

- Discuss the implications of each position

- Apply the debate between these positions to the construction of the globalization narrative more broadly

- Read Steger, Chapter 5

- Read Rees in McGlinchey, Chapter 9

- Take the World Country Quiz at globalquiz.org http://en.globalquiz.org/top-culture-facts/

- Complete Learning Activity #1

- Watch the Al Jazeera video “Edward Said – Framed: The Politics of Stereotypes in News” https://youtu.be/4QYrAqrpshw

- Watch the video “Orientalism in Western Popular Music” https://youtu.be/ieqv2RdYeiY

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Read the Washington Post opinion piece “Trump’s dangerous thirst for a clash of civilizations” (available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trumps-dangerous-thirst-for-a-clash-of-civilizations/2017/07/06/fb5398ea-6282-11e7-a4f7-af34fc1d9d39_story.html?utm_term=.f2362d6efd21)

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Watch the video “The Convergence of Cultures: Shaping Great Cities” https://youtu.be/h8RyNCXVaUE

- Watch “White Party – A lesson in Cultural Appropriation” https://youtu.be/Ipx3fKn4G3U

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Complete Discussion Questions.

- 9/11

- Americanization

- cultural appropriation

- cultural diffusion

- cultural globalization

- Eurocentric

- Global War on Terror (GWOT)

- globalization

- Greenwich Mean Time

- Hegemonic

- Hybridization

- Jihad vs McWorld

- modernity

- Orientalism

- The Conflict of Civilizations

- western cultural imperialism

- ‘white man’s burden’

- world cities

- Steger, Chapter five, “The Cultural Dimension of Globalization” in Steger, Manfred S. Globalization: a Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Rees, Chapter nine, “Religion and Culture.” In International Relations, edited by Stephen McGlinchey, 98-111. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2017.

Learning Material

Figure 5-1: Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clifford_Geertz Permission: Courtesy of Randall Hagadorn.

As we have done in the past two modules, our first task is to define cultural globalization. Culture is notoriously difficult to define. As Steger points out, it can be used to define the totality of human experience. This is legitimate in the sense that culture embodies history, language, norms, values, and processes of socialization to name just a few aspects. Culture provides meaning to our lived experiences. Clifford Gertz (1973) argues we are,

…incomplete or unfinished animals who complete ourselves through culture…

However, such a broad definition is problematic in that it simply encompasses too much. It is not possible for us to explore everything that gives meaning to life, to every person, who lives everywhere. I am not sure it is even possible for us to accomplish this in our own individual lives. Therefore, we need to arrive at a working definition of culture. Steger posits the ‘cultural’ as the process of symbolic construction, articulation, and dissemination of meaning. Our working definition of globalization is the expansion and intensification of social relations and consciousness across world-time and world-space. Combining the two, and the preceding discussion of differing views of cultural globalization, it is posited that cultural globalization is the expansion and interaction of cultural constructs that may dominate, compete, or cross fertilize with other cultural constructs. Our goal in this module is to explore these different understandings of cultural globalization. Is cultural globalization a process of global homogenization and domination? Does it define the new boundaries of global conflict? Or does it describe the process of hybridization that has given us New York pizza and salsa music?

Before moving on, let us assess your knowledge of world geography and facts.

- Take the World Culture Quiz at globalquiz.org http://en.globalquiz.org/top-culture-facts/

- Post your score on the Poll below. Your score will be anonymous.

[yop_poll id=”5″]

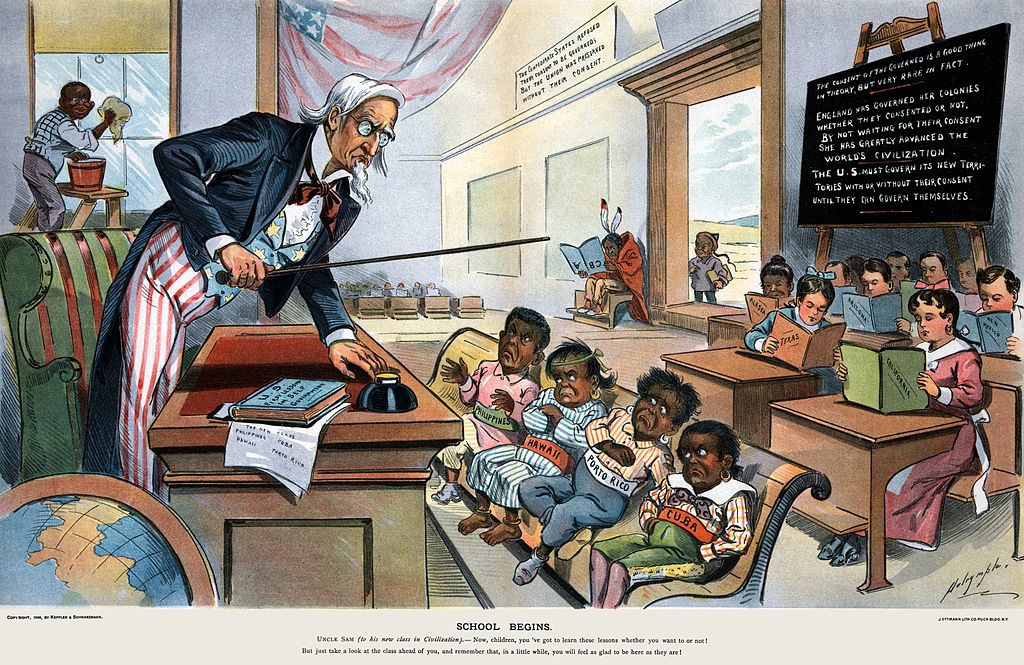

Figure 5-2: “School Begins” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ASchool_Begins_(Puck_Magazine_1-25-1899%2C_cropped).jpg Permission: Public Domain, Courtesy of Louis Dalrymple (1866-1905), artist Puck magazine, publisher Keppler & Schwarzmann.

Colonialism not only exported the economic and political structures of the metropole, it also exported the metropole’s culture. The colonial powers represented a form of European universalism. The British, the French, the Spanish, and the Portuguese portrayed their states, and Europe more generally, as advanced military and economic powers whose superiority rested on a superior culture. This is often summed up with the now much discredited ‘white man’s burden’, coined in Rudyard Kipling’s poem about the Philippine-American War.

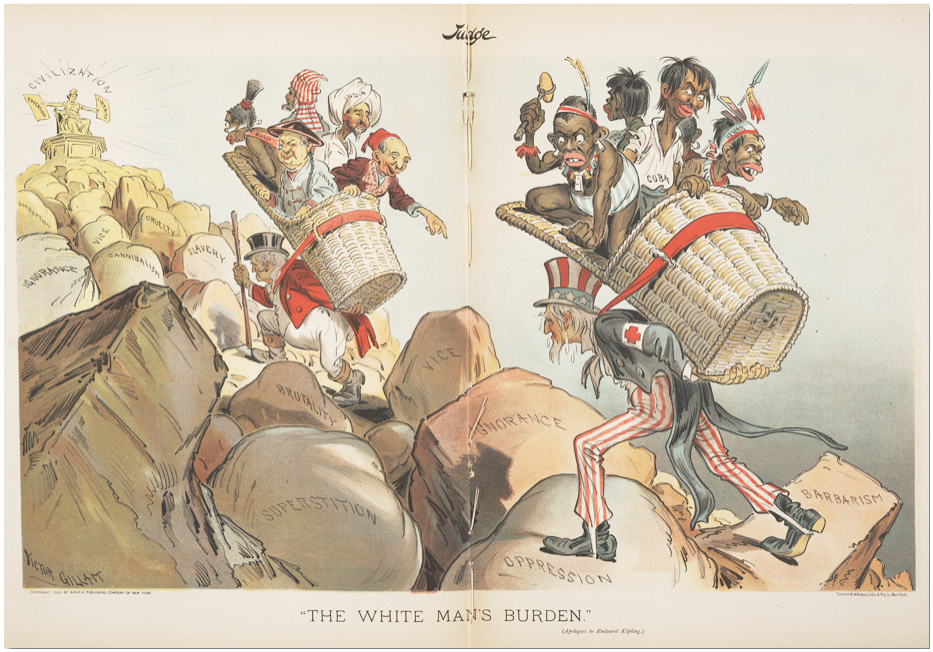

Figure 5-3: “The White Man’s Burden” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3A%22The_White_Man’s_Burden%22_Judge_1899.png Permission: Public Domain, Courtesy of Victor Gillam.

He argued the Americans should colonize the Philippines, even if neither the US government nor the American people wanted to, because of the country’s status. That the US, much like the European colonizers before them, had an obligation as an advanced culture to civilize the Philippines. European and American cultures have since subjugated so many other cultures, leading to what Lévi-Strauss laments as an emerging monoculture or homogenization of culture.

While the physical colonization of the ‘other’ has fallen into disrepute, it is argued that cultural imperialism has continued where colonization has left off. The western culture being exported is multi-faceted. It includes economic aspects, capitalism and the free-market for example. It includes political facets, like representative liberal democracy and individual rights, both of which rest on broader cultural norms and values which privilege liberal ideals of secularism and individualism. This western cultural imperialism thesis is quite pervasive. The world has been carved up into western modeled states through colonialism.

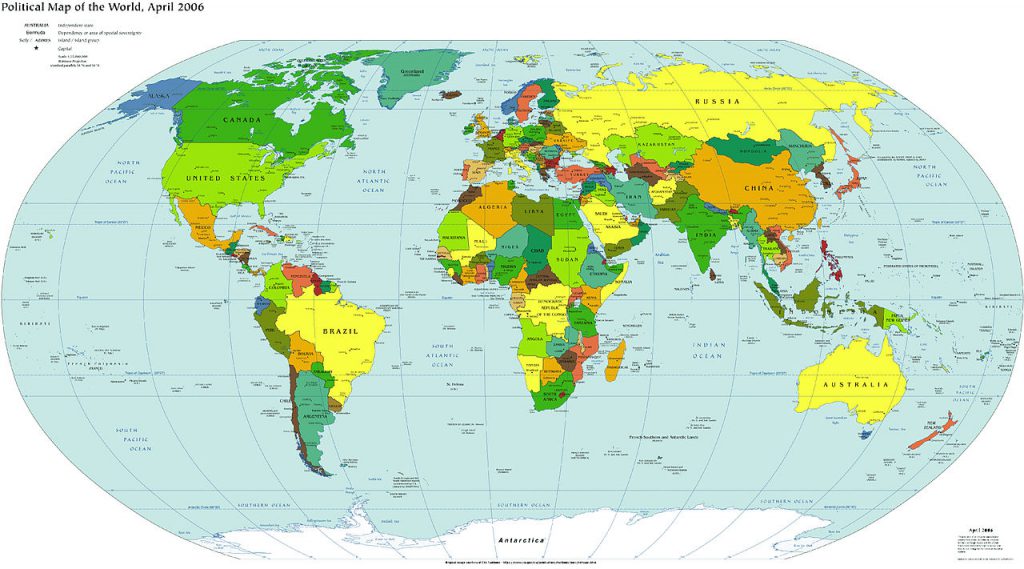

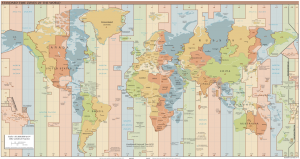

Figure 5-4: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AWallpaper-world-map-2006-large.JPG Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain, Courtesy of Neutravo.

Figure 5-5: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AStandard_World_Time_Zones.png Permission: Public Domain, Courtesy of Hellerick.

Global covenants use the language of the West and the most important institutions of global governance are largely based in western states. The global economy is regulated by western dominated institutions and legitimated by western ideologies. The very definition of global time has been carved into zones, originally based on Greenwich Mean Time, which centers the world on the UK. An important voice in this narrative is Edward Said and his concept of Orientalism: a Eurocentric discourse which defines the world outside of the West as the ‘other’. By its nature, this narrative sets the West as the standard by which all others are to be judged. This ‘other’ is instrumentally characterised as an exotic, if underdeveloped and unchanging, place. This exoticism is the point of the image Said chose for the cover of his book Orientalism.

Figure 5-6: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AJean-L%C3%A9on_G%C3%A9r%C3%B4me_-_Le_charmeur_de_serpents.jpg Permission: Public Domain, Courtesy of Jean-Léon Gérôme.

This view of the “Orient” stands in contrast to the dynamic West with its advances in science, economics, politics, and cultural artifacts.

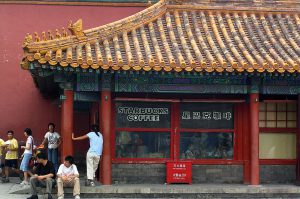

Figure 5-7: “Starbucks at the Forbidden City” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AStarbucks_at_the_Forbidden_City.jpg Permission: CC-BY-SA-3.0, Courtesy of Mr. Tickle

This contrast both elevates the West and justifies historical colonialism as well as more contemporary forms of cultural imperialism. Cultural imperialism is so powerful because unlike colonization which requires armies and physical coercion, it is ideational. If the West is able to convince the ‘other’ that its ideas and values are superior via its books, movies, music, economies, political structures, and institutions, the battle has nearly been won. The ‘other’ has internalized the dominant culture and self-polices its own actions and even values. The dominant contemporary form of cultural imperialism is Americanization.

Figure 5-8: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AAm%C3%A9ricanisation_du_monde.JPG Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Treehill.

It is argued that America has played an almost hegemonic role in terms of the manufacture and dissemination of contemporary western culture. Specifically, American movies, music, and social media are prevalent around the world. American technology firms build the hardware and write the software that powers our digital interconnectedness. The US pioneered global media and the 24 hours news cycle. While other states and their companies have become increasingly competitive, they emulate the American models that preceded them. The American model has become the gold standard by which others are judged and, as such, Americanization continues even when it is non-American companies making technological innovation.

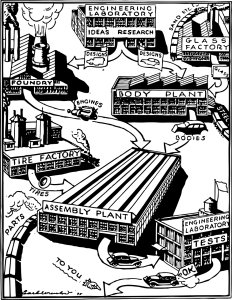

Figure 5-9: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/factory-automobile-assembly-line-35108/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain.

At a deeper level, Americanization has influenced the very basis of social organization by privileging global rationalization via modernity. Modernity depersonalizes cultural relations, replacing it with technocratic processes: the assembly line, mass production, even the organization of our suburban communities.

Beyond, the corporations that have been agents of Americanization, the US Government has constructed a global regulatory framework that privileges the commodification of media and culture, with an emphasis on free trade in information and cultural products. Even in Europe, the impact of Americanization is lamented as American companies from Apple and Microsoft to Uber, Twitter, and Facebook are playing an increasingly important cultural role.

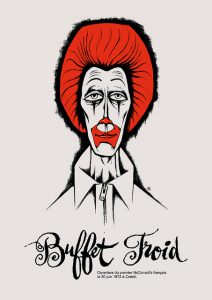

Figure 5-10: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/christopherdombres/6995303316/Permission: Public Domain.

McDonalds, in particular, has been the target of Anti-Americanization, especially in France where one McDonalds was filled with apples, another filled with fowl. In 2000, a French farmer named Jose Bové convinced nine other farmers to drive their tractors through a McDonalds under construction. Another McDonalds was bombed in 2000 leading to a death.

Figure 5-11: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/hive/12522026165/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Jason Wilson.

Other attacks have occurred in Russia, Chile, Ecuador, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Turkey, Spain, and Italy. These attacks highlight the resistance to Americanization and to cultural homogenization more broadly.

- Watch the video “Edward Said – Framed: The Politics of Stereotypes in News”

- Watch the video “Orientalism in Western Popular Music”

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your journal

- What is Orientalism?

- What explicit and implicit stereotypes are created by Orientalism?

- Identify an example of Orientalism in western media today.

- How does Orientalism contribute to cultural homogenization?

Figure 5-12: Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/brampitoyo/5204308566/ Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Bram Pitoyo.

Benjamin Barber coined the phrase Jihad vs McWorld, which argues that the 21st century would be defined as cultural conflict. At the root of this conflict was a tension between tribalism and global consumerism. Global consumerism is McWorld: it is expressed by the extension of capitalism via the large western corporations that saturate the globe with western cultural products. Jihad is tribalism: it is expressed by a refutation of global corporatism and a retrenchment of local values and local culture, possibly but not necessarily even militantly.

Figure 5-13: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Teheran_US_Barry_Kent2.JPG Permission: CC-BY-SA-3.0 Courtesy of Robert Wielgórski a.k.a. Barry Kent.

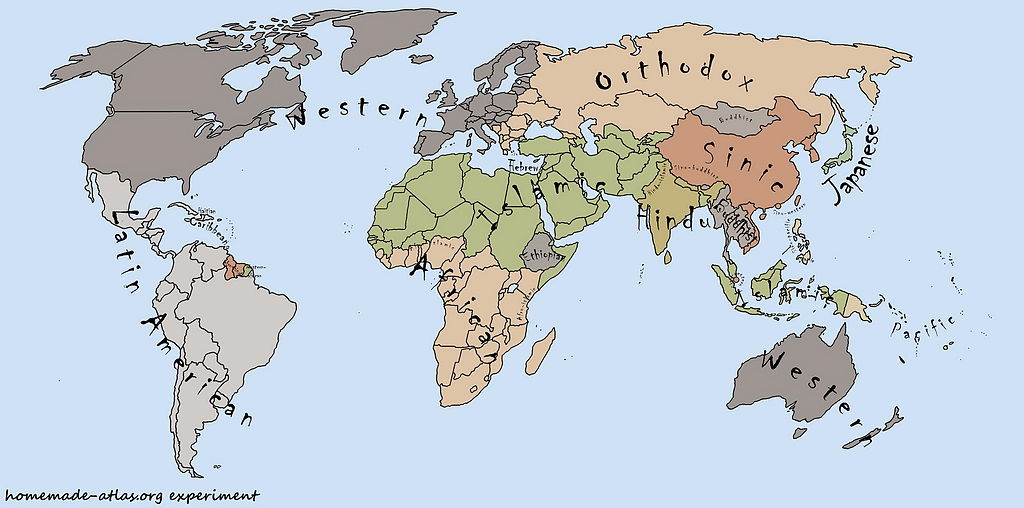

While Barber identified a broad pushback against western cultural imperialism, and in particular its expression through global consumerism, Samuel Huntington redrew the world map into The Conflict of Civilizations. Rather than locate conflict through ideology or economics, he saw the post-colonial world coming into its own and clustering into civilizational opposition to the dominance of western civilization. These others include the Latin American, the Slavic Orthodox, the Sinic, the Hindu, the Buddhist, and the African civilizations. But most importantly, he saw a clash between the western and the Islamic civilizations. Huntington argued the demise of the Soviet Union was crucial as the USSR was a common enemy to both the West and the Islamic world. With its absence, the West and the Islamic World confronted each other.

Figure 5-14: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Civilizations.jpg Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of Ionut Cojocaru.

Figure 5-15: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AWar_on_Terror_montage1.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Poxnar.

Huntington’s thesis would seem to have been validated on September 11th, 2001, or as it is most commonly known 9/11. In the 1990s, tensions had been flaring as the West supported dictatorial regimes in the Middle East for their own national interest and some Islamic states like Iran, and non-state actors like al Qaeda, had pushed back against western meddling. The conflict between Israel and the Palestinians was, and continues to be, a particular rallying point in the Islamic world. However, it would be Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda that would lock the West and much of the Islamic Middle East into conflict. Osama bin Laden was a Saudi national incensed at the presence of US troops in Saudi Arabia during the First Gulf War. After being expelled by the Saudi regime, he began to organize, agitate, and oppose American forces in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Yemen while being sheltered by the Taliban in Afghanistan. When bin Laden and al Qaeda attacked the twin towers in New York, the West embarked on an existential Global War on Terror (GWOT).

The list of enemies in this war started with al Qaeda and the Taliban and now focus on Boko Haram and ISIS. There are many critics of the culture clash narrative and in particular the Clash of Civilizations thesis. But it does highlight the significant pushback against western culture and its homogenizing impact. China has been mounting a significant challenge to western cultural influence. At home, China has erected the Great Fire Wall of China which polices what Chinese citizens can access online. Abroad, China is recreating the new Silk Road. It is investing heavily in Africa. It is working with other states such as Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa to set up a New Development Bank. Russia is challenging western dominance in Eastern Europe, specifically in Crimea and Ukraine. Turkey is reverting to a pre-Atatürk era under Recep Tayyip Erdogan, enshrining conservative values. A pink tide, or shift towards the political left, in Latin America has pushed back against American led neo-liberalism. All of these examples, but most especially the events of 9/11 and those that followed from it, question the cultural homogenization narrative. However, taken to the extreme, the cultural conflict narrative is also problematic in that it essentializes the world into the West versus the rest or civilizational constructs.

- Read the Washington Post opinion piece “Trump’s dangerous thirst for a clash of civilizations” (available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trumps-dangerous-thirst-for-a-clash-of-civilizations/2017/07/06/fb5398ea-6282-11e7-a4f7-af34fc1d9d39_story.html?utm_term=.f2362d6efd21)

- Use the following question to guide an entry in your journal.

- How is President Trump drawing on the Clash of Civilization narrative?

- Why does Eugene Robinson argue this is misguided?

- How does this question the utility of the Culture Clash narrative?

- Does the cultural clash narrative still retain any insight?

Figure 5-16: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACOB_data_Canada.PNG Permission: CC-BY-SA-3.0, Courtesy of Kransky.

It looks at how ideas flow between cultures through personal contact, economic transactions, and through digital media. It looks at how dominant trends are transformed by local customs to become something altogether new. Hybridized culture creates both a thin global culture and at the same time localized versions. Take language for example. English has increasingly become the lingua franca of international business, international politics, and digital media. But at the same time, localized versions of English are everywhere: in Korea, there is Konglish; in Spain, there is Spanglish; and in China, there is Chinglish. The European Union has its own version of English that works as a via medium for the 28 member states to draft, debate, and pass legislation. Food moves with immigrant communities, changing and adapting to its new home. Just compare a New York pizza and one from Napoli, Italy. Or perhaps try and introduce an American invention, alfredo sauce, to a traditional Italian grandmother.

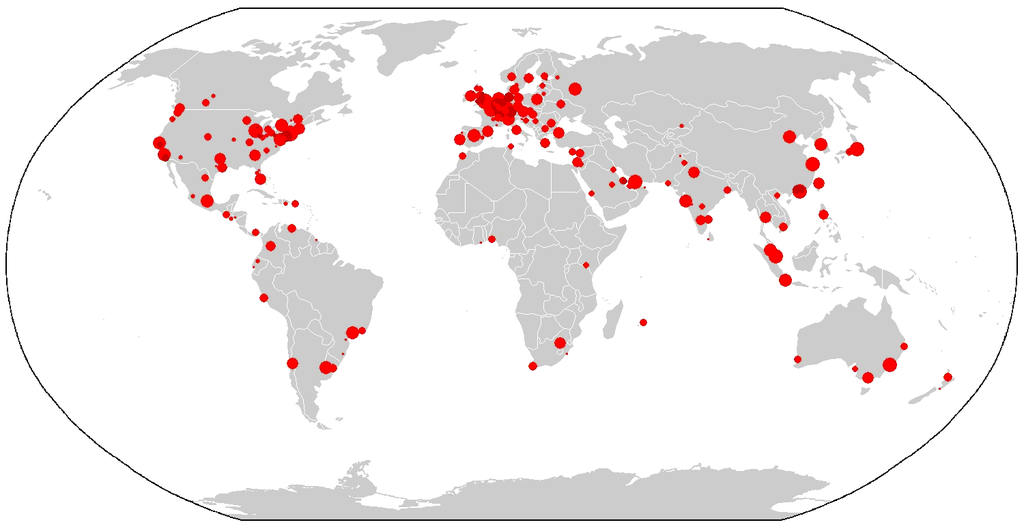

Hollywood has been mirrored in Bollywood and Japanese Anime has been embraced around the world. American pop music has found local expression in Korea through K-pop and Japan as J-pop. It is in music that dynamic cultural flows can be readily discerned. While reprehensible, slavery brought African music to the US and Brazil, leading to the blues, jazz, and rock and roll. Salsa originated in Caribbean but has a strong global following. Winners of the tier one and two 2016 World Salsa Championship included dancers from Brazil, Peru, Panama, the US, Italy, and Mexico. Moreover, local versions of Salsa have emerged including Afro-Latino, Cali, LA, and New York-style. Some musical genres consciously mix and adopt sounds from perceived roots with contemporary styles. Some artists consciously seek out other sounds, creating a stand-alone genre called ‘world music’. Such blending exemplifies glocalization, where a fusion between the global and the local creates a distinctive synthesis. Often at the site of glocalization are the new world cities, places like London, New York, Tokyo, Paris, and Singapore. These are the centers of economic, political, and cultural innovation. This is where large diaspora communities exist, bringing their culture with them and bringing those cultures into contact with others. Some try to recreate the homeland in their new countries. But in doing so, they often create a version that is something a bit different, something new. Others embrace their adopted country and its culture, but once again it is often a hybridized version that emerges as the new culture is viewed and acted upon through pre-existing cultural norms and values.

Figure 5-17: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GaWC_World_Cities.png Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of Interchange88.

All of the examples above posit cultural globalization not as being territorially fixed. Neither is it a homogenizing/imperializing force, nor necessarily constituting rigid conflictual boundaries. Rather, cultural hybridization views culture as rooted in particular spaces that may or may not be contained by political borders. These cultural spaces are fuzzy at the edges, blending with neighbouring culturally spaces, and creating new hybrids where they meet. They are also transplanted in new spaces, by the flow of people through migration for example, via traditional media like music and movies, and increasingly through the ideas that flow through the internet digitally.

However, one last tangentially connected point needs to be addressed. Cultural hybridization must be differentiated from cultural appropriation. This discussion is usually rooted in the tension between cultural diffusion and cultural appropriation. Cultural diffusion is the spread of cultural practices from one place to another. Cultural appropriation is the use or adoption of elements of another culture, often by a dominant or privileged culture, without knowledge of the meaning attached to it. More serious forms occur when this appropriation is done for profit and is especially problematic when it concerns significant religious or cultural practices. This often correlates to the Orientalism argument; that cultural dress, practices, and images are adopted because they are seen as exotic or mysterious. An illustrative example has been the appropriation of Indigenous images in the world of fashion. From high fashion in Paris or Milan to the shops in the mall, Indigenous images and traditional styles are blatantly evident. An example of this problematic practice is the use of the headdress in fashion advertising. The headdress is ceremonial and given as a gift from a community to acknowledge role and identity. When used by fashion houses, its meaning is lost and demeaned. It is being commodified by another culture for profit. Further, it is often sexualised, made exotic, reinforcing the Orientalist tradition so prominent in cultural appropriation.

- Watch the video “The Convergence of Cultures: Shaping Great Cities”

- Watch “White Party – A lesson in Cultural Appropriation”

- Use the following question to guide an entry in your journal.

- What is a great city?

- How is the cultural identity of a city formed?

- What is cultural appropriation?

- How do the two videos contrast cultural hybridization with cultural appropriation?

Cultural globalization as a concept is under defined. The first narrative of cultural globalization is defined as a process of homogenization driven by dominant cultures, most often seen as Americanization. For proponents of this position, the perception that Starbucks or McDonalds can be found on every corner of every major city and that movies and music are increasingly American is just the tip of the homogeneity iceberg. Beneath these obvious signs of American cultural imperialism lies the regulatory regimes that privilege western culture. And beneath that layer lies the global internalization of modernity which depersonalizes cultural relations, privileges technocratic processes, and fundamentally reorganizes the values and norms of society. From this perspective, cultural globalization is cultural imperialism. Or paraphrased from the Borg of Star Trek fame, “We are the Americans. Your biological and technological distinctiveness will be added to our own. Resistance is futile.” The second narrative of cultural globalization is defined as a clash, even conflict. Barber’s Jihad vs McWorld and Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations may differ in how they see pushback occurring and its possible consequences, but they do agree that cultural globalization is a space of tension. That the narrative of inevitable homogeneity is over stated and that such attempts at cultural dominance will lead to resistance. For Barber, global consumerism generates parochial and tribal responses. For Huntington, the relative decline in western power and the end of the Cold War will lead to civilizational conflict. He argues this may play out in a variety of ways but the most likely is the West versus Islam and many point to 9/11 and the Global War on Terror as evidence to support his assertions. The third narrative of cultural globalization is defined as a process of hybridization. For proponents of this position, culture may be rooted in particular societies but is not co-terminus with states. Rather, cultural boundaries are fuzzy and they blend with neighbouring cultures, sometimes creating new cultural constructs. Moreover, culture is transplanted via people who move from one place to another and via media which project cultural values and practices. Importantly, world cities have played an enormous role in facilitating the hybridization of culture through music, art, dance, and food. From the hybridization perspective, both globally dominant cultures and locally tribal cultures exist and exercise influence but not alone and not in a determining fashion. Between them and within them exists hybridized cultural constructs that blend both in multidirectional flows. The problem that we confront is which narrative is correct. The answer is that none are completely right and it is arguable all play a role in shaping contemporary cultural globalization in different places and different times. Perhaps the question is not which one is right but rather which logic makes the most sense in specific contexts.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

9/11: the term used to describe the events of September 11, 2001 in the United States; the day on which Islamic terrorists, believed to be part of the Al-Qaeda network, hijacked four commercial airplanes and crashed two of them into the World Trade Center in New York City and a third one into the Pentagon in Virginia. The fourth plane crashed into a field in rural Pennsylvania.

Americanization: the process by which people or countries become more and more similar to Americans and the United States.

cultural appropriation: The unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society.

cultural diffusion: the spread of cultural beliefs and social activities from one group to another. The mixing of world cultures through different ethnicities, religions and nationalities has increased with advanced communication, transportation and technology.

cultural globalization: the rapid movement of ideas, attitudes, meanings, values and cultural products across national borders.

Eurocentric: centered on Europe or the Europeans; especially reflecting a tendency to interpret the world in terms of European or Anglo-American values and experiences

Global War on Terror (GWOT): After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the Bush administration declared a worldwide "war on terror," involving open and covert military operations, efforts to block the financing of terrorism, new security legislation, and more. The US called on other states to join in the fight against terrorism, stating that "either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists."

Glocalization: Products or services designed to benefit a local market while at the same time being developed and distributed on a global level.

Greenwich Mean Time: the mean solar time at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London. Greenwich Mean Time was formerly used as the international civil time standard, now superseded by Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).

Hegemonic: ruling or dominant in a political or social context. A hegemonic power is in the position of being the strongest and most powerful and therefore able to control others.

Hybridization: The process by which a cultural element such a food, language, or music blend into another culture by modifying the element to fit cultural norms. It is a blending between two or more components.

Jihad vs McWorld: the 1995 book by Benjamin Barber that analyses the conflict between consumerist capitalism versus religious and tribal fundamentalism. The term is used to describe the paradoxical and powerful interdependence of the forces.

Modernity: the development of capitalism and industrialisation, as well as the establishment of nation states and the growth of regional disparities in the world system. The period has witnessed a host of social and cultural transformations such as stratification and exploitation of certain societies.

Orientalism: Edward Said’s concept that powerful people/states interpret less powerful people/states in a way that allows the former to dominate the latter. These attitudes often included thinking of “Orientals” as "the Other" in a way that allowed those from the West to subjugate them.

The Conflict of Civilizations: Phrase used by Samuel P. Huntington in a 1993 journal article and in a later book in an attempt to explain the causes, character, and consequences of divisions among people and between states after the collapse of Eastern European Communism in the late twentieth century. Huntington argues that the primary source of conflict will be people’s cultural and religious identities.

western cultural imperialism: the process and practice of promoting one culture over another. Often this occurs during colonization, where one nation overpowers another country, typically one that is economically disadvantaged and/or militarily weaker.

‘white man’s burden’: from the poem by Rudyard Kupling, the alleged duty of white colonizers to care for non-white indigenous subjects in their colonial possessions.

world cities: a city generally considered to be an important node in the global economic system. It is sometimes called a world centre or global city.

References

- “A Corporation Under Attack.” BBCWorldservice.com. Accessed October 22, 2017, bbc.co.uk/worldservice/specials/1616_fastfood/page8.shtml

- Abreu, Martha. “The legacy of slave songs in the United States and Brazil: musical dialogues in the post-emancipation period.” Revista Brasileira de História, 35 (69), 2015, 177-204. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1806-93472015v35n69009

- Chandler, Adam. “How McDonald's Became a Target for Protest.” The Atlantic.16 April 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/04/setting-the-symbolic-golden-arches-aflame/390708/

- Chausovsky, Eugene. “Why Civilizations Really Clash.” Stratfor Worldview. 10 January 2016. https://www.stratfor.com/analysis/why-civilizations-really-clash

- DeRoche, Annelise. “Appropriation of Indigenous Culture in the Fashion Industry.” 17 October 2016. https://medium.com/@a.deroche/appropriation-of-indigenous-culture-in-the-fashion-industry-6f02387ebd26

- Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures Selected Essays. ACLS Humanities E-Book (Series). New York: Basic Books, 1973.

- Knipp, Kersten. “Erdogan takes on Ataturk.” Deutsche Welle. 11 April 2017. http://www.dw.com/en/erdogan-takes-on-ataturk/a-38391293

- Kopp, Ed. “A Brief History of the Blues.” All About Jazz. 16 August 2005. https://www.allaboutjazz.com/a-brief-history-of-the-blues-by-ed-kopp.php

- Renn, Aaron M. “What is a Global City?” New Geography. 7 December 2012. http://www.newgeography.com/content/003292-what-is-a-global-city

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. A World on the Wane. New York: Criterion Books, 1961.

Supplementary Resources

- Huntington, Samuel P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

- Barber, Benjamin R. Jihad vs. McWorld. 1st ed. New York: Times Books, 1995.

- Hopper, Paul. Understanding Cultural Globalization. Cambridge: Polity, 2007.