Overview

As we have seen in the previous two modules, global interconnectedness is intimately connected to the idea of economics. The early Silk Road connected the Korean Peninsula to the Mediterranean, with its trade routes driving transformation of the societies through the introduction of new languages, religions, and culture. Technological innovation drove the industrial revolution, connecting metropoles with colonies through global trade routes. Some of the most innovative contemporary drivers on the internet are e-commerce merchants, connecting businesses to consumers globally in a digital world. Therefore, it should be no surprise that economics dominates the contemporary narrative of globalization. However, this is a very specific narrative of globalization that is rooted in the post-war ideas of a liberal economic order. The argument is that as we deregulate and connect markets through free trade, we specialize and innovate, and as a result, efficiency is enhanced, poverty is reduced, and the world is a more stable and peaceful place. And there is some data to support this – for example, global poverty has been reduced. But it is not the whole story as growing inequality demonstrates or the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. For some, economic globalization is seen as the saviour of the world’s poor, whose logic will eradicate extreme poverty and transition us to an almost borderless world of peace and prosperity. For others, economic globalization is a game whose rules have been written by the rich for the rich, whose logic will ensure that the game is rigged to keep the status quo. In order to address some of these issues, this module will begin with a look at the dominant narrative of economic globalization. We will then look at the structure of the post war global economic order and the issues it has generated. Finally, we will examine some other narratives surrounding globalization.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Outline the main ideas that constitute the liberal economic order

- Identify the main institutions and processes of the post-war economic order

- Expose some of the contemporary problems with the post-war economic order

- Discuss alternative models of economic globalization

- Read Steger Chapter 3

- Read McGlinchley Chapter 8

- Complete Learning Activity #1

- Watch the TED talk by Richard Wilkinson: How economic inequality harms societies. https://www.ted.com/talks/richard_wilkinson?utm_campaign=tedspread–a&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Read Parag Khanna’s article “These 25 Companies Are More Powerful Than Many Countries” in Foreign Policy: http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/15/these-25-companies-are-more-powerful-than-many-countries-multinational-corporate-wealth-power/

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Read Salman Sakir’s article “Globalization is only a good thing if it benefits all groups of society”. http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/salman-sakir/globalization_b_5992002.html

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Complete Discussion Questions

- Bretton Woods System

- economic nationalism

- embedded liberalism

- Extreme poverty

- Foreign Direct Investment

- General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

- global inequality

- Global South

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD)

- International Financial Institutions (IFIs)

- International Monetary Fund (IMF)

- Latin American debt crisis

- liberal economics

- liberal economic order

- mercantilist

- Multinational Corporations (MNCs)

- neoliberalism

- Organization of Petroleum Exporting States (OPEC)

- Stagflation

- Structural Adjustment Programs

- Transnational Corporations (TNCs)

- Washington Consensus

- World Bank

- World Trade Organization

- Steger, Chapter three, “The Economic Dimension of Globalization” in Steger, Manfred S. Globalization: a Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Walzenbach, Günter. “Global Political Economy.” In International Relations, edited by Stephen McGlinchey, 87-97. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2017.

Learning Material

What is economic globalization? We have a working definition of globalization as the expansion and intensification of social relations and consciousness across world-time and world-space. Economics has to do with the production of goods, the provision of services, the system of their exchange, and consumption. Putting the two together, economic globalization refers to these processes having a global frame; that economics is being organized on a global scale. This leads to the next question: how has economics been globalized? What form has it taken and why? What are the implications of this particular form of economic globalization? These are fundamental questions to human welfare. This module will look at the liberal ideas that have informed contemporary economic globalization. It will then look at the institutions that have shaped it, the problems that have been generated, and then ask you to think about why economic globalization has taken this form and whether this is appropriate.

One of the issues that we will be tackling in this module is global inequality.

Before moving on, let us assess your knowledge of inequality

- Take the Oxfam inequality quiz: http://www.oxfam.org.uk/education/resources/inequality-quiz

- Post your score out of 12 on the poll below. Your score will be anonymous.

[yop_poll id=”2″]

In the latter half of the 19th century, the global economy was highly influenced by liberal economics: an emphasis on the free market and a laissez-faire policy of minimal government intrusion into the economic affairs of individuals and society. It was rooted in the belief that a free individual had the requisite rationality to make the best decision for themselves. As each individual maximized their own individual welfare, society as a whole would benefit. That didn’t not mean that the government did not have a role to play; rather, the government should restrict its activities to enforcing contracts and the maintenance of order. In terms of international economics, there was a preference for free trade as the market, absent political interference, was argued to be self-correcting. If a country ran a deficit in trade/services, there would be a net outflow of gold. This would result in a devaluation of their currency and would subsequently make exports less expensive. Cheaper exports would lead to increased competitiveness and restoring equilibrium in the balance of trade. This very liberal international economic order had been supported by the dominance of the British in the international economic order. However, the unification of Germany in 1871 challenged this economic order with the adoption of mercantilist policies. Further, as tension rose between the European states, nationalism and protectionist policies took hold. The global economy was increasingly seen as another realm of national conflict. Both World Wars, and the Great Depression during the inter-war years, were characterized by illiberal policies.

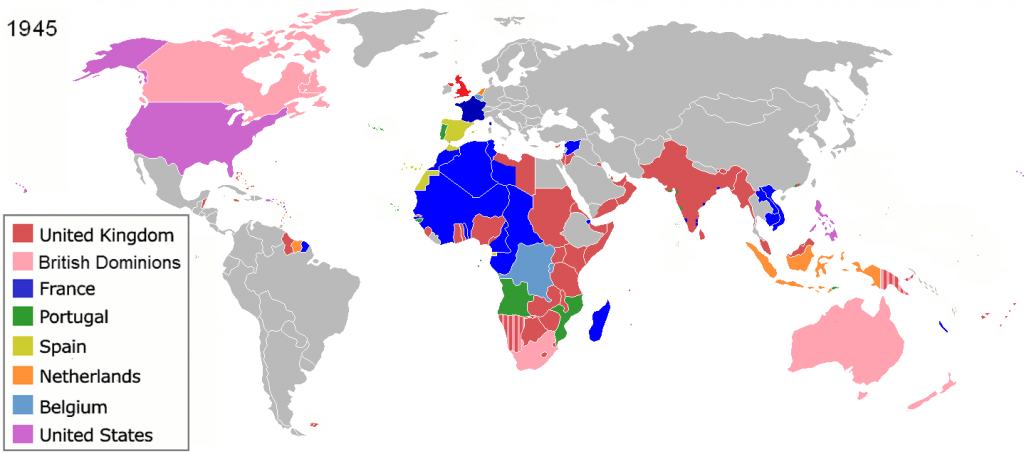

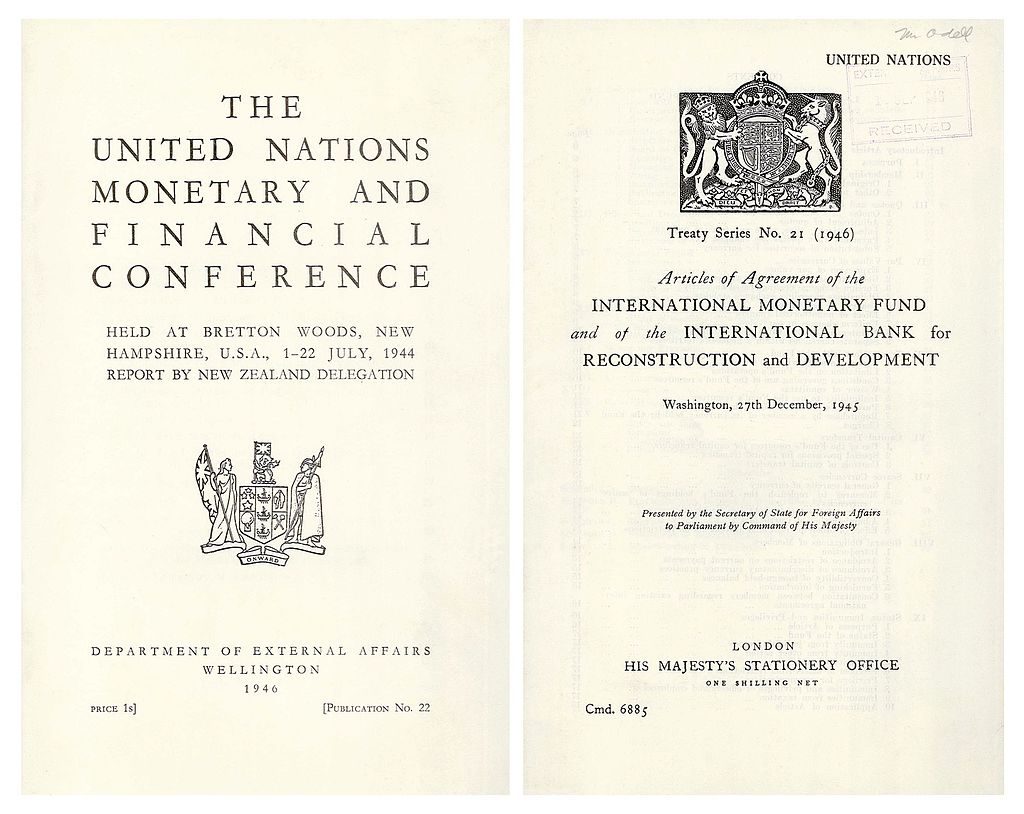

However, as American and British policy makers began the serious work of planning for the post-war world, they confronted two principle issues. First, Europe was devastated and would need to be rebuilt but European states lacked the resources to do so. Second, they needed to construct a global monetary and trade system that would avoid the instability and economic nationalism witnessed during the inter-war years. In 1944, at Bretton Woods, it was proposed to create three international institutions to manage a new global economic order.

Figure 3-1: Source: https://flic.kr/p/9JeYnq Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Mike Licht.

Figure 3-2: Source: http://www.wikiwand.com/en/International_Bank_for_Reconstruction_and_Development Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 3-3: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Colonization_1945.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Anis Katsaris.

Figure 3-4: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_Trade_Organization_(logo_and_wordmark).svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of World Trade Organization.

The third institution was the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which would become the World Trade Organization in 1995. The GATT, and later the WTO, was tasked with fostering trade liberalization by reducing barriers to trade and constructing rules for trade. This would include, under the WTO, a binding trade dispute settlement mechanism. Together, these institutions would support the Bretton Woods System: a negotiated monetary order whereby signatories agreed to maintain their exchange rate within plus or minus 1% by pegging their currency to gold. The US dollar would act as a reserve currency and guarantee convertibility to gold. The three institutions would support states in this goal.

Figure 3-5: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:International_Monetary_Fund_formed_1945_(15839176617).jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Archives New Zealand from New Zealand

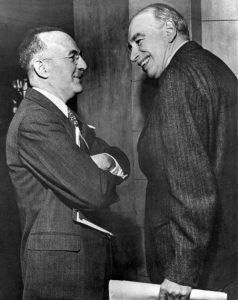

Figure 3-6: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WhiteandKeynes.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of International Monetary Fund.

The two key Architects Assistant Secretary, U.S. Treasury, Harry Dexter White (left) and John Maynard Keynes, honorary advisor to the U.K. This system lasted until 1971 and was called embedded liberalism. Embedded liberalism attempts to reconcile the tension between an open trade system and the welfare state with close to full employment. It was argued that the two were incompatible given the volatile nature of international capital which had a tendency to move quickly to wherever it can find the most profit. This economic system was ‘liberal’ in the sense that it aimed to establish and maintain an open system of international trade and services. But it was also ‘embedded’ in a political and social framework that allowed controls to be placed on capital and therefore provide room for expanding social welfare However, this came to an end in 1971 when Nixon ended the convertibility of the US dollar to gold.

Figure 3-7: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nixon_30-0316a.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Oliver F. Atkins.

The US was facing serious economic problems. There was a surplus of dollars in circulation. The printing press had been utilized to cover foreign aid, military spending in places like Vietnam, and expensive domestic policies. Money was leaving the country via foreign investment. The US did not have enough gold to cover the currency in global circulation, meaning the dollar was overvalued, resulting in foreign exchange runs on the dollar. Without the convertibility of the US dollar to gold, it would not be able to anchor the monetary systems and essentially ended the Bretton Woods system and embedded liberalism.

The global economy in the 1970s was subsequently characterized by uncertainty. The western developed economies entered into a recession due to the oil crises of 1973 and 1979 and the increased competition of Newly Industrialized Countries or NICs. The first oil crisis of the period came via an embargo imposed by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting States, or OPEC, on those states that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War in 1973. The price of oil quadrupled within a year, badly damaging industry and consumer spending.

Figure 3-8: Source: http://en.academic.ru/dic.nsf/enwiki/152956 Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance

with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

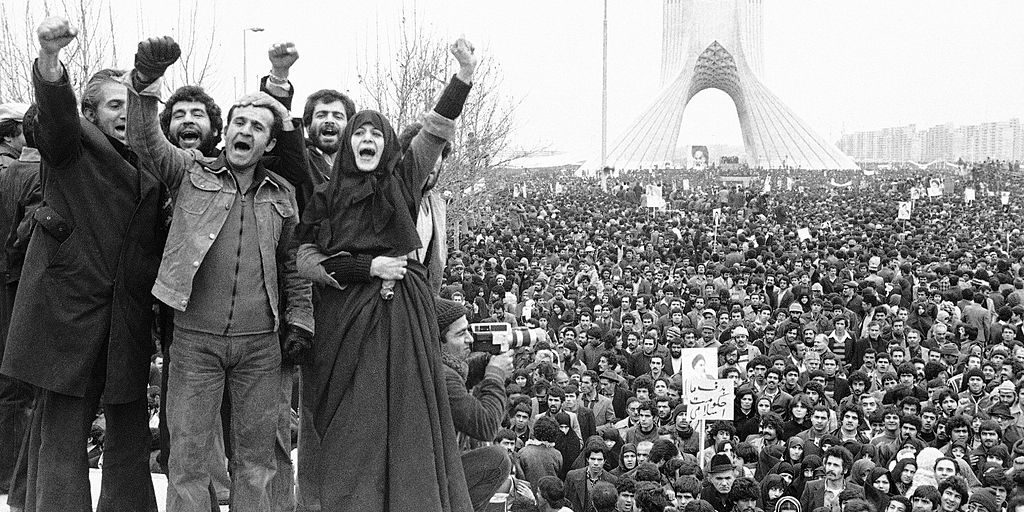

The second oil crisis would occur in 1979 following the Iranian Revolution. While oil supply only decreased by 4% this time, the memory of 1973 sent shockwaves through the western developed economies. The Iran-Iraq War of 1980 further reduced the supply of oil and exacerbated economic challenges in the West.

Figure 3-9: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iranian_Revolution_in_Shahyad_Square.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Aristotle Saris.

Figure 3-10: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iran-Iraq_war-gallery.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0

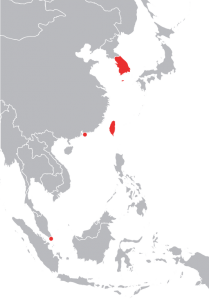

Figure 3-11: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Four_Asian_Tigers.svg Permission: CC-BY-SA-3.0 Courtesy of Zuanzuanfuwa.

The disruption caused by the two oil shocks were compounded by the rise of the NICs, primarily the four Asian Tigers – Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. These four states were able to generate strong growth, especially in the manufacturing of steel which challenged the viability of core industrial centers in the US and Europe.

One of the major outcomes of this was stagflation, particularly in the US. Up until the 1970s, average inflation rates were 2.5% per year. In the 1970s, they were 7.06% with a high of 13.29% in 1979. At the same time, the economy was slowing and unemployment was high. A stagnating economy plus inflation equals stagnation, a situation which greatly restricts the government’s policy options. Policy to address the stagnating economy will further increase inflation and vice versa. embed

At the same time as the western developed economies were struggling, a second problem was brewing in the form of a Latin American debt crisis. Latin American states had been growing rapidly in the 1960s and 70s and states like Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico took out loans for infrastructure programs. They were seen as low risk borrowers while, at the same time, demand from developed western states for loans was in decline due to the financial recession. Finally, the international banks had a surplus of dollars from the OPEC states derived from the oil crisis, motivating them to provide these loans to states in the Global South. However, when the Bretton Woods system ended and interest rates shot up, these states were increasingly unable to service their loans. This was exacerbated by their own economic downturn driven by lower commodity prices and the fact that the loans were denominated in US dollars while their own currencies were depreciating in value. By 1983, the cumulative debt of the region equaled 50% of its GDP. As it became apparent these states may default on their loans, the public and private lenders in the developed western states began to fear economic contagion: that a default in Latin America could threaten the stability of the global economic system. States would default forcing banks into insolvency, leading to a breakdown of the system.

It was in the economic climate of both the stagflation in the developed world and debt crisis in the developing world that a new economic order emerged: neoliberalism, also known as the Washington Consensus. he basic tenets of neo-liberalism are:

- Privatize public enterprises

- Deregulate the economy

- Liberalize trade and industry

- Cut taxes

- Control inflation through the supply of money

- Control, often through legislation, organized labour

- Reduce public expenditures, particularly social spending

- Cut government bureaucracy

- Expand international markets

- Liberalize global financial flows

These policies were implemented both in the developed world, first in the US and the UK, as well as in the developing world. They were implemented at home to arguably boost competitiveness in the global market. Some states in the Global South followed neoliberal prescriptions willingly, Chile for example. But the rest were coerced into the neoliberal economic order via the debt crisis and the policies of the IMF and World Bank. The IMF had reinvented itself after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971; it became the lender of last resort. If no one else was willing to loan a state money, the IMF would step in but with conditions. Similarly, the World Bank would provide loans for development projects but with conditions. During crisis, states turn to these institutions for loans. The conditions attached to these loans were called Structural Adjustment Programs. Essentially, the loans were given as long the states followed the tenets of neoliberalism. It was known this would cause social dislocation in the short- to medium-term, but it was argued these conditions would bring the states back into liquidity. This program would grow exponentially with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, including during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. These policies would create great economic and political instability, first in the global south through the 1980s and 90s and later in the Global North following the 2008 financial crisis. An important outcome of neoliberal policy has been increased inequality both within states and between states. And inequality has played a big role in creating the conditions for the political and economic crises mentioned above. In the next section we will look at the three main developments of economic globalization in an era of neoliberalism that have led to these outcomes.

One of the most detrimental outcomes of neoliberalism is greater inequality in both the Global South and in the Global North. This TED Talk by Richard Wilkinson looks at how inequality impacts us. Rather than looking at ‘the other’, people living in faraway places with much different political, social, and economic norms, this video looks at how income inequality impacts western developed states.

- Watch the TED talk by Richard Wilkinson: How economic inequality harms societies.

- Use the following question to guide an entry in your journal.

- What impact does income inequality have on our society?

- What are the two ways to reduce inequality?

- How do you think inequality is linked to neoliberalism?

Steger identifies three developments in contemporary economic globalization as being most pertinent: internationalization of trade and finance, increased power of Transnational Corporations (TNCs) or Multinational Corporations (MNCs), and the enhanced role of the IMF, World Bank, and WTO also collectively known as the International Financial Institutions (IFIs).

The most immediately perceived facet of economic globalization is the sharp rise of trade. In 1947 there was 57 billion dollars in world trade. In 2016 there was 16.05 trillion dollars’ worth of trade. In 1960, there was 414 billion dollars in the export of services. In 2016, there was 4.93 trillion dollars’ worth of trade.

Beyond these numbers, we see the impact of trade in what we wear, what we eat, what we drive, what entertains us, and on what devices. Most products are constituted by resources from one place, manufactured wholly or partially in another place, and shipped to the store where you bought it (or your computer screen if bought online). Behind this process, the product was conceived by someone perhaps in another place altogether, marketed, contracted, insured, and coordinated by more people. The headquarters of the company may be in a different country than where it does its manufacturing, while its financial operation may be in another place altogether. If you had a problem with the product, you may have spoken to a call center located in still yet another country. In all, the products you use every day may have directly or indirectly passed through the hands and minds of numerous people in numerous places. This is economic globalization in trade and services. Companies can seek the cheapest means to acquire resources, manufacture products, pay taxes, and develop markets. Pro-trade advocates argue the benefits of this system accrue to consumers who have more choice and cheaper goods as well as to foreign workers who have the opportunity to raise their standard of living. There is some data to support this argument. For example, the percentage of people living under extreme poverty has been halved between 1990 and 2015. Moreover, a quick look at your grocery store will demonstrate the choice of goods available at a relatively low cost. Those who are critical of the free trade argument point to different statistics. They argue that according to the Human Development Report half of the world’s population still lives on less than 2.50$ a day, or moderate poverty, and 80% lives on less than 10$ a day; that global inequality has reached the point where eight men own the same wealth as the poorest 3.6 billion people. The Internationalization of trade has been less visibly joined by the internationalization of finance through the deregulation of interest rates, removal of capital controls, the privatization of banks/financial institutions, and the growth of investment banking. If we compare international financial assets to global trade the difference is quite stark. In 2014, global trade hit its highest point, 19.17 trillion dollars’ worth of goods. However, international financial assets, which includes stocks, bonds, and all the securities available to invest in, was about 294 trillion dollars in 2014.Now these numbers do include domestic financial assets as well. But with the deregulation of international finance, capital can flow to wherever profit can be made. This is an important point. For the most part, this is not capital being utilized to finance manufacturing, the creation of stuff to be traded and sold. This is speculative finance, where the trading of an economic asset is undertaken in the hope to make substantial gains while acknowledging a degree of risk. Traders are looking for trends and shifts in commodity prices or exchange rates, betting on their future performance. It is highly volatile and highly competitive. And it is prone to bubbles, where trading can expand the value of a good far beyond its actual market value. Which is a problem, as we will see when discussing the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

The second key development has been the increased power of TNCs. Transnational corporations are businesses that have a parent company and subsidiary units in more than one country. In 1970 there were 7,000 TNCs and in 2015 there were 100,000. The top 200 TNCs maintain headquarters in North America, Europe, China, Japan, South Korea, and Mexico. The top TNCs are able to challenge the most privileged political actor in the world – states.

Figure 3-12: Source: https://flic.kr/p/5VKByX Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Stuart Caie.

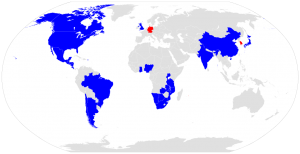

Apple has more reserve cash, 215 billion US dollars, than two-thirds of the world’s states. The top 10 biggest banks control nearly 50% of global assets under management. TNCs were able to become so plentiful and powerful because of the deregulation of labour, resources, and production conditions, particularly in the global south. TNCs use foreign direct investment (FDI) to set up facilities in other countries. In 2016, global net inflows of FDI were 1.757 trillion US dollars. The sheer size of companies like Wal Mart, Apple, Samsung, Royal Dutch Shell, or Volkswagen generates their own economic gravity. They are able to coerce states, shape trade routes, and lobby international institutions. Some even argue that TNCs are so large, they have their own foreign policy. 147 TNCs, which Steger calls super connected TNCs, control 40% of the shares of world’s large blue chip and manufacturing firms. In 2016, the Forbes list of the 2000 largest TNCs had combined revenues of 39 trillion US dollars, profits of 3 trillion US dollars, and assets worth 162 trillion dollars. Of the top 100 top global economies in 2015, 69 were companies and 31 were states. Walmart takes the 10th spot right after Canada.

Figure 3-13: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WalMart_international_locations.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Andershalden.

Figure 3-14: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Walmart_footprint.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Magog the Ogre.

This raises a host of questions. If there are more businesses on the top 100 economies than states, who is making the rules? Who is ensuring these TNCs are socially responsible? Sustainable? These are the questions that are increasingly being asked following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

The third key development has been the increasingly visible and muscular role played by the IFIs. As mentioned earlier, the IMF had originally been set up to help states in a balance of payment crises. This was to ensure that states remain committed to the exchange rate system set up in 1944 and not manipulate the value of their currency for economic advantages. This role came to an end in 1971 when the US cancelled the convertibility of the US dollar to gold, the linchpin of the Bretton Woods system. The IBRD had been set up to finance post-war reconstruction and development projects in Europe. In the 1950s, the mandate of the World Bank was expanded to include providing loans to developing states in the global south, most often recently decolonized states. In order to understand some of the subsequent shifts of the IFIs, it is pertinent to look at how decision making happens. In both the IMF and World Bank, voting rights are weighted to quota subscriptions that reflect the relative size of their economies. This ensures that western developed economies hold the majority of the votes, 57% to be exact. The US holds 17% of the vote by itself while the poorest 165 states have only 29% of the vote. One tangible result of weighted voting is that the head of the World Bank has always been an American and the head of the IMF has always been a European. This is important when the turbulent 1970s hit the developed western economies. The IMF took on the role of lender of last resort. When a state had nowhere else to go, they could turn to the IMF for help. But this help came with conditions called Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs). This achieved two goals. First, it was very important to the western developed economies that the sovereign loans held by states in the global south not default. They feared a contagion effect: if one state were to default, this would take down the banks that are owed money which would start a chain reaction of other indebted states and highly leveraged financial institutions. Second, the SAPs forced open the states in the global south to FDI from the global north, to goods from the global north, and to better terms for the global north to access resources. The World Bank would come to pay a similar role, by adding their own conditions to loans that complemented those of the IMF. While contagion was averted, many economies in the global south have remained heavily indebted and have undergone boom and bust cycles repeatedly. For example, in 2010, developing states paid out 184 billion US dollars in debt servicing but only received 134 billion US dollars in foreign aid. By the 2000s, the IFIs had adjusted their language. Instead of SAPs the IFIs now speak of Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, country ownership, and good governance. And these are important steps towards a more equitable development model. But as we saw in the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2009 Greek Debt Crisis, the IFIs are still at best the domain of classical liberal economists. And if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. For the IFIs if you see a flailing state, it is going to look like a problem of an inefficient economy.

- Read Parag Khanna’s article “These 25 Companies Are More Powerful Than Many Countries” in Foreign Policy: http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/15/these-25-companies-are-more-powerful-than-many-countries-multinational-corporate-wealth-power/

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your journal.

- How was Anderson Consulting able to achieve such success?

- What is a metanational?

- Do you think companies will have more influence than states in economic globalization?

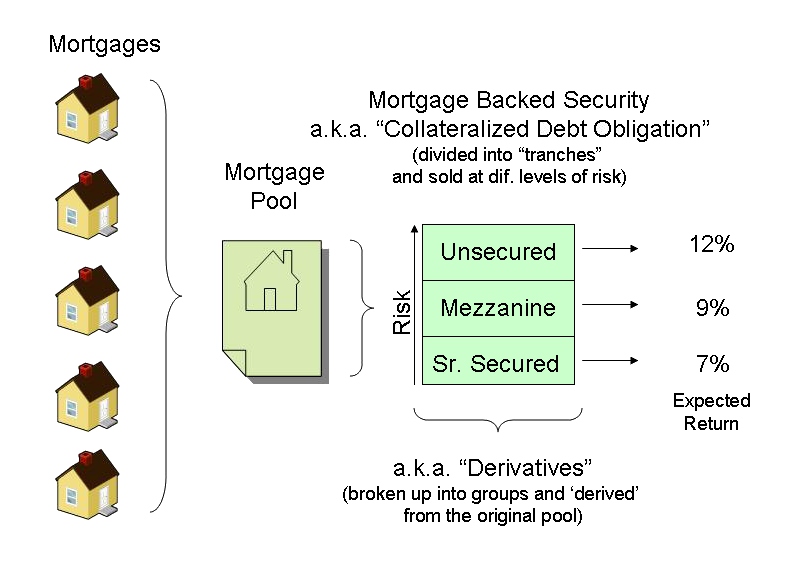

Figure 3-15: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mortgage_backed_security.jpg Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of WTBrooks.

Figure 3-16: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/debt-loan-student-mortgage-1376061/ Permission: CC0 1.0

The buyers of these securities included pension funds, insurance companies, and foreign investors. For example Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, or by their proper names the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), owed 5 trillion US dollars to investors in mortgage obligations. When the crisis grew and began to spread, large companies like Lehman Brothers used short term securities, called commercial paper, to cover debts. When these began to default, the market spooked and everybody sold anything that might have exposure to residential mortgage-backed securities. This became a systemic crisis as trust was gone, lending dried up, and even solid companies that needed access to credit were punished.

Government stepped in with stimulus spending to avoid further contagion because financial institutions had become too large to fail – because of deregulation. The consequences? There was a global recession with high unemployment and contagion to other markets like the Eurozone debt crisis in Portugal, Ireland, Spain, Cyprus, and most importantly Greece.

The second contemporary issue of economic globalization is the rise of inequality but at the same time a decrease in poverty. By definition, absolute poverty means you do not have the resources to meet the basic needs of life. Things like food and shelter. An important measurement here is the 1.90$/day benchmark of extreme poverty. Inequality on the other hand is the unequal distribution of assets, wealth, and income either within the state or between states. Extreme poverty, has declined. As previously mentioned, extreme poverty has been halved between 1990 and 2015; almost 1 billion people have been lifted out of poverty and it is possible extreme poverty could be eradicated by 2030. However, inequality is growing and is at its highest point in the last three decades. Oxfam has pointed out the in 2016, 8 men own the same wealth as the bottom 3.6 million people in the world. In the developed world, wages are stagnating or even falling while executive compensation is growing. 7 out of 10 people live in a country where income inequality is growing. Other metrics of inequality include gender, health, education, and wellbeing. In OECD countries, women still earn 16% less than men and top female earners earn 21% less. Women are underrepresented in legislatures and top management positions in business. They are also more than one and half times likely to live in poverty. There are inequalities in access to health, by sex, age, geography, and finance. Canada is a good example, access to health care is very differentiated by northern/southern communities, and rural/urban communities for example. Inequality in education leads to lower wages and shorter life expectancies. Overall, inequality has demonstrable impact on both the wellbeing of the individual and of society as a whole. There are no definite answers as to why inequality is growing but the timeline suggests that the shift to the neoliberal economic order has something to do with it. Neoliberalism sought to release the market, constrain labour and state spending. It has created cycles of boom and bust economies. All of which facilitate the aggregation of wealth by the few to the detriment of the many.

The final contemporary issue is the question of who economic globalization serves. Many debate the advantages of global trade and finance, whether benefits trickle down, and how poverty can be alleviated. But are these the right questions? If we see repeated financial crisis and growing inequality, shouldn’t we ask who economic globalization benefits? That is the goal of the last learning activity.

- Read Salman Sakir’s article “Globalization is only a good thing if it benefits all groups of society”. http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/salman-sakir/globalization_b_5992002.html

- Use the following questions to guide an entry in your journal

- What are the pros and cons of economic globalization?

- Do the pros outweigh the cons?

- How can economic globalization benefit all groups?

Economic globalization is how the production of goods, the provision of services, the system of their exchange, and consumption is now operating in a global frame. This module looked at the liberal and neo-liberal ideas that have shaped contemporary economic globalization. It examined the institutions that have supported this international liberal economic order and the impact of the turn to neoliberalism. Importantly, the domestic struggle with stagflation in the 1970s and the international threat of the Latin American debt crisis in the 1980s, are used to explain this turn. The dominant trends of contemporary globalization were explored, specifically the internationalization of trade and finance, the increase of TNCs, and the increased role of the IFIs. Finally, we address the contemporary issues of the Global Financial Crisis, rising inequality, and the question of whom economic globalization serves. That leaves us ready to tackle the next question in Module 4 – political globalization.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Bretton Woods System: the international monetary arrangement, agreed upon by the allied nations in 1944 in Bretton Woods, US, that created the IMF and World Bank and that set up a system of fixed exchange rates with the US dollar as the international reserve currency.

economic nationalism: an ideology which favors policies that emphasize domestic control of the economy, labor, and capital formation, even if this requires the imposition of tariffs and other restrictions on the movement of labor, goods and capital.

embedded liberalism: the global economic system and the associated international political orientation as they existed from the end of World War II to the 1970s. The system was set up to support a combination of free trade with the freedom for states to enhance their provision of welfare and to regulate their economies to reduce unemployment.

Extreme poverty: according to the World Bank, “extreme poverty” is defined as living on less than 1.90$ a day (US dollars). This figure was updated in 2015 from the previous definition of 1.25$ a day.

Foreign Direct Investment: an investment made by a company of one country in another country, in the form of establishing new business operations or acquiring assets in the other country, such as ownership or controlling interest in a foreign company.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT): Multilateral international treaty first created in 1947 and frequently amended (most recently in 1994, called the "Uruguay Round"). GATT provides for fair trade rules and the gradual reduction of tariffs, duties and other trade barriers, for goods, services and intellectual property.

global inequality: financial inequality amongst different people around the world. Global inequality can relate to to income, health, education, access to energy, water, amongst other issues.

Global South: a term that has been emerging in transnational and postcolonial studies to refer to what may also be called the "Third World" (i.e., Africa, Latin America and the developing countries in Asia), "developing countries," "less developed countries," and "less developed regions”

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD): an international financial institution that offers loans to middle-income developing countries. The IBRD is the first of five member institutions that compose the World Bank Group and is headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States.

International Financial Institutions (IFIs): the institutions created at the Bretton Woods Agreement including the IMF, the IBRD (later the World Bank), and the GATT (later the WTO)

International Monetary Fund (IMF): an international organization created for the purpose of standardizing global financial relations and exchange rates. The IMF generally monitors the global economy, and its core goal is to economically strengthen its member countries.

Latin American debt crisis: a financial crisis that originated in the early 1980s (and for some countries starting in the 1970s), often known as the "lost decade", when Latin American countries reached a point where their foreign debt exceeded their earning power and they were not able to repay it.

liberal economics: the classical theories of economics emphasizing the concept of the free market and laissez-faire policies, with the government's role limited to providing support services.

liberal economic order - global free trade establishment. Critics sometimes refer to this as the Washington Consensus, which implies that this system works mostly in the favor of the United States at the expense of smaller countries

Mercantilist: economic theory and practice common in Europe from the 16th to the 18th century that promoted governmental regulation of a nation's economy for the purpose of augmenting state power at the expense of rival national powers

Multinational Corporations (MNCs): has facilities and other assets in at least one country other than its home country. Such companies have offices and/or factories in different countries and usually have a centralized head office where they coordinate global management.

Neoliberalism: a policy model that transfers control of economic factors from the public sector to the private sector. It takes from the basic principles of neoclassical economics, suggesting that governments must limit subsidies, make reforms to tax law in order to expand the tax base, reduce deficit spending, limit protectionism, and open markets up to trade. It also seeks to abolish fixed exchange rates, back deregulation, permit private property, and privatize businesses run by the state.

Organization of Petroleum Exporting States (OPEC): a group consisting of 12 of the world's major oil-exporting nations. OPEC was founded in 1960 to coordinate the petroleum policies of its members, and to provide member states with technical and economic aid. OPEC is a cartel that aims to manage the supply of oil in an effort to set the price of oil on the world market, in order to avoid fluctuations that might affect the economies of both producing and purchasing countries.

stagflation: persistent high inflation combined with high unemployment and stagnant demand in a country's economy.

Structural Adjustment Programs: economic policies which countries must follow in order to qualify for new World Bank and IMF loans and help them make debt repayments on the older debts owed to commercial banks, governments and the World Bank.

Transnational Corporations (TNCs): incorporated or unincorporated enterprises comprising parent enterprises and their foreign affiliates. A parent enterprise is defined as an enterprise that controls assets of other entities in countries other than its home country, usually by owning a certain equity capital stake

Washington Consensus: a set of ten economic policy prescriptions considered to constitute the standard reform package promoted for crisis-wracked developing countries by Washington, D.C.–based institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, and the US Treasury Department.

World Bank: an international financial institution that provides loans to countries of the world for capital programs. It comprises two institutions: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), and the International Development Association (IDA).

World Trade Organization: the only global international organization dealing with the rules of trade between nations. At its heart are the WTO agreements, negotiated and signed by the bulk of the world's trading nations and ratified in their parliaments.

References

Khanna, Parag and David Francis. “These 25 Companies Are More Powerful Than Many Countries.” Accessed October 9, 2017. http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/15/these-25-companies-are-more-powerful-than-many-countries-multinational-corporate-wealth-power/

Lund, Susan, Eckart Windhagen, James Manyika, Philipp Härle, Jonathan Woetzel, and Diana Goldshtein. “The New Dynamics of Financial Globalization.” August 2017. Accessed October 9, 2017. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/the-new-dynamics-of-financial-globalization

O’Brien, Patrick K. and Geoffrey Allen Pigman. “Free Trade, British Hegemony and the International Economic Order in the Nineteenth Century.” Review of International Studies 18, no.2 (April 1992): 89-113. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20097288?seq=22#page_scan_tab_contents

Ocampo, José Antonio. “The Latin American Debt Crisis in Historical Perspective.” Accessed October 9, 2017. http://policydialogue.org/files/publications/The_Latin_American_Debt_Crisis_in_Historical_Perspective_Jos_Antonio_Ocampo.pdf

Oxfam Canada. “Your Questions Answered: Oxfam’s Inequality Report.” Accessed October 9, 2017. https://www.oxfam.ca/blogs/your-questions-answered-oxfam%E2%80%99s-inequality-report

Sanyal, Sanjeev. “The Random Walk: Mapping the World’s Financial Markets 2014.” Hong Kong: Deutsche Bank Research, 2014. Accessed October 9, 2017. https://etf.deutscheam.com/DEU/DEU/Download/Research-Global/47e36b78-d254-4b16-a82f-d5c5f1b1e09a/Mapping-the-World-s-Financial-Markets.pdf

United Nations. “Goal 1:End Poverty in all its Forms Everywhere.” Accessed October 9, 2017. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/poverty/

World Bank Group. “External Debt Stocks, Total (DOD, Current US).” Accessed October 9, 2017.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.DOD.DECT.CD?locations=XM

Green, Duncan. “The World’s top 100 economies: 31 countries; 69 corporations” The World Bank. Accessed Oct 9, 2017. https://blogs.worldbank.org/publicsphere/world-s-top-100-economies-31-countries-69-corporations

Mishel, Gould, and Bivens. “Wage Stagnation in Nine Charts”, Economic Policy Institute. Accessed October 9, 2017. http://www.epi.org/publication/charting-wage-stagnation/

OECD. “Inequality.” Accessed October 9, 2017. http://www.oecd.org/social/inequality.htm

Supplementary Resources

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. Making Globalization Work. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 2006.

- Rivoli, Pietra. The Travels of a T-shirt in the Global Economy : An Economist Examines the Markets, Power and Politics of World Trade. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2005.

- Cammack, Paul. "The UNDP, the World Bank and Human Development through the World Market." Development Policy Review 35, no. 1 (2017): 3-21.