Overview

Environmental issues are one of the most vexing global problems today. The air we breathe, the water we drink, and the land that sustains us are universal needs. Every person in every place depends on a healthy environment. Some environmental problems are primarily domestic and can be attended to by domestic law, but others are transnational or even global and require bilateral or multilateral responses.

Figure 10-1: Source: https://flic.kr/p/p7Wi7U Permission: Courtesy of United States Government Work.

Take for example the Cuyahoga River fire of 1969. On June 22 of that year, a river in the United States caught fire. It was not the first, nor the worst, nor even the last river to catch fire, but it captured the imagination of the US and sparked federal environmental legislation. The fire was made possible by the unregulated dumping of industrial waste into the river, a common practice occurring in many American rivers. This was a local event, caused by local pollution, and was addressed by state and national legislation. This fire was a major impetus for the creation of the Federal Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency in 1972, and the drafting of the Clean Water Act in 1972.

However, the pollution of the Cuyahoga River was also of international concern as the river empties into Lake Erie, one of the Great Lakes that border both the US and Canada. A bilateral agreement to tackle such pollution, ‘The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement’, was reached in 1972 and was last amended in 2012.

Figure 10-2: "Great Lakes From Space" Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Lakes_from_space.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of SeaWiFS Project, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, and ORBIMAGE.

However, dealing with issues at the global level is much more difficult. As we will see, there are issues in defining the problem, identifying solutions, and getting agreement on implementing them. Making the issue even more pressing is the argument that achieving solutions to these environmental issues is quickly becoming existential: literally a question of life and death for everyone on the planet.

Like the other topics we have covered in this class, globalization has impacted environmental issues. The birth of the industrial age, exponential population growth, the rise of global trade, the promotion of a consumer lifestyle… they have all led to a situation where the planet’s carrying capacity is at, or has already exceeded, its limit of sustainability. Moreover, if everyone on the planet consumed as much as the average American or Canadian, we would need four planets to sustain us. If we use the United Arab Emirates as the baseline, we would need almost five and a half planets. Environmental issues manifest in climate change, deforestation, fish stock collapse, desertification, air pollution, and access to clean drinking water. The sources of these problems increasingly require a global response. In this module, we will take a brief look at the rise of global environmental issues, look at the responses they have generated, and conclude with a discussion of climate change as perhaps the most pressing global environmental issue.

Figure 10-3: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AWorld_map_of_countries_by_ecological_footprint_(2007).svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Jolly Janner.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Define contemporary global environmental issues

- Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of global responses to environmental issues

- Explore the issue of climate change and the problems of agreeing on a global response

- Read Pacheco-Vega, chapter fifteen in McGlinchey

- Take the survey to assess your ecological footprint: http://www.footprintcalculator.org/

- Complete Learning Activity #1

- Watch the TEDx video ‘Environmentalism, Urgency, and Seizing the Day’ by Andrew Wong: https://youtu.be/0q3K2p_Oobg

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Watch “25th Anniversary Documentary – Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer” https://youtu.be/7nY6exEIP4A

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Watch James Hansen’s TEDx talk Why I must speak out about climate change” https://www.ted.com/talks/james_hansen_why_i_must_speak_out_about_climate_change?utm_campaign=tedspread–b&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling

- Ambient global temperature

- Bilateral

- Climate change

- Compliance

- Earth Summits

- Epistemic communities

- ‘Free ride’

- Friends of the Earth

- Global commons

- Global environmental governance

- Global warming

- Greenhouse gases

- Greenpeace

- Kyoto Protocol

- Montreal Protocol

- Multilateral

- Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

- Ozone layer

- Paris Agreement

- Planet’s carrying capacity

- Romanticism

- Sierra Club

- Silent Spring

- Sustainable development

- ‘Tragedy of the commons’

- UN Environment programme

- Pacheco-Vega, Raul, chapter fifteen, “The Environment” In International Relations, edited by Stephen McGlinchey, 163-171. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2017.

Learning Material

Before moving on, let us assess your ecological footprint

- Take the this survey to assess your ecological footprint: http://www.footprintcalculator.org/

- Post your score on the live poll

Figure 10-4: “Cambio-climatico” Source: via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACambio-climatico.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0. Courtesy of Inchi9.

Some of the earliest environmental movements in Europe sprang from Romanticism, a humanist movement focused on the beauty of nature and human emotion. These romantics challenged the predominant view of nature as a resource to be utilized by humans for their own interests. Instead, they saw beauty and interdependency between humans and the environment. More substantively, environmental movements expanded during the industrial revolution of the late 19th century which generated increasing environmental externalities: deforestation, unrestricted air pollution, and disposal of industrial waste. This led to the befoulment of the rivers, the lakes, the land, and the air.

Figure 10-5: “Sierra Club” Source: https://flic.kr/p/8HEQgi Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Cliff.

It also motivated early conservationists like Henry David Thoreau, who argued we must live in harmony with nature, and John Muir, who established the Sierra Club in 1892. The Sierra Club was one of the earliest national environmental pressure groups in the US. It was founded to protect the Sierra Nevada, hence the name, but expanded to look at land management, infrastructure projects, and environmental issues across the US.

In Canada, early naturalists included Samuel de Champlain and Catherine Parr Traill who documented the flora and fauna they encountered during their exploration and settlement in Canada. The early 20th century saw movements to protect endangered species, from buffalo to whales. Many countries instituted national policies to protect aspects of the environment and regulate industrial waste. An important early effort at international conservation was the 1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. It evolved from simply regulating the whaling industry to trying to enforce a moratorium on whaling altogether. This shift remains contentious to this day with Japan, Norway, and Iceland still operating whaling fleets.

Figure 10-6: “Silent Spring” Source: https://flic.kr/p/2AZjGs Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Frank Hebbert.

However, the modern environmental movement really began to take shape in the 1960s, often dated to the publication of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring in 1962. The book detailed the negative impact of pesticides on the environment and by extension the threat that human activity was, and many would argue still is, posing to our own food chain. Essentially, she argued we were killing ourselves by polluting the very things that sustain us: food, air, and water. The book proved a tipping point in the US, generating a debate in the general public about the need to regulate behaviour to protect the environment, and in particular economic activity. In the 1970s, important and influential interest groups emerged, like Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace. They pursued public campaigns to protect wildlife, highlighting for example the plights of tigers and the deeply troubling ivory trade. Friends of the Earth was founded as an international anti-nuclear movement but quickly evolved to cover global issues from desertification and the melting of the polar ice caps to issues of economic justice and critiquing neoliberal economics.

Figure 10-7: “Friends of the Earth” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AFOE_horz_logo.png Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of FOE, US.

Figure 10-8: “Greenpeace Logo” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGreenpeace_logo.svg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Stichting Greenpeace Council.

Greenpeace started in Canada as an anti-nuclear group, specifically the testing of nuclear weapons on the Alaskan island of Amchitka. It has evolved into one of the most preeminent international environmental groups, now based in the Netherlands with offices in 40 countries and almost three million members.

Figure 10-9: “Greenpeace Paises” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGreenpeace_paises.PNG Permission: CC BY-SA 2.5 Courtesy of Tappoz.

Figure 10-10: “Maurice Strong” Source: https://flic.kr/p/cgXreW Permission: CC BY NC ND 2.0 Courtesy of Sergio Greif.

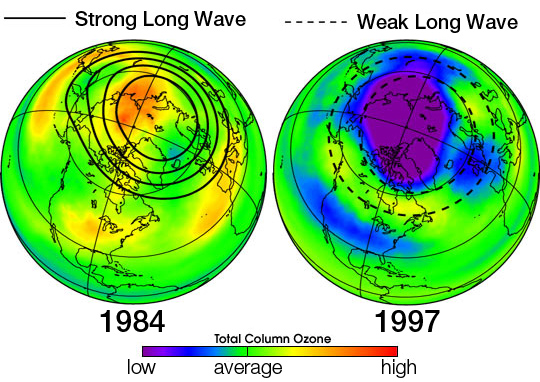

At the international level, the first UN Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm in 1972, led by Canadian under-secretary Maurice Strong. This was the first of what would become known as Earth Summits, conferences held every 10 years to generate ideas and assess progress on sustainable development. The inaugural Earth Summit in 1972 produced the first ‘state of the environment’ report. It also led to the establishment of the UN Environment programme. In the 1980s, epistemic communities begin to form around light pollution, ocean pollution, noise pollution, air pollution, et cetera. Some of these communities were relatively isolated, constituted by marine biologists or astronomers for example. However, the discovery of the hole in the ozone layer created a more substantial and global response. The hole was caused by Chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, and was strongly linked to the increase of UV-B radiation and a subsequent threat of skin cancer. CFCs were commonly used in refrigerants, aerosol propellants, and solvents. The common narrative at the time linked everyday actions like cooling our cars and creating big hair styles were increasing our chances of dying. A narrative very similar to that generated by Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring. The result was the total ban on CFCs via the Montreal Protocol in 1987.

Figure 10-11: “Uars Ozone Waves” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AUars_ozone_waves.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of NASA.

Figure 10-12: “Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Brundtland” Source: https://flic.kr/p/agcp4w Permission: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Courtesy of World Economic Forum.

Another important event in the 1980s was the 1983 UN World Commission on Environment and Development led by former Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Brundtland. The Commission produced the Brundtland Report which first established the idea of ‘sustainable development’.

An important aspect of sustainable development was recognizing the need to reconcile both the environmental and economic aspects of development. The meltdown of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor in 1986 sparked substantial opposition to nuclear energy, something recently brought back to the world’s attention with the 2011 nuclear disaster in Fukushima.

Figure 10-13: “Chernobyl Disaster” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AChernobyl_radiation_map_1996.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.5 Courtesy of CIA Factbook, Sting (vectorisation), MTruch (English translation), Makeemlighter (English translation)

Figure 10-14: “Fukushima Daiichi Disaster” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ATowns_evacuated_around_Fukushima_on_April_11th%2C_2011.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Mayhew.

] In the 1990s, global warming and the north/south divide became hot environmental topics and were directly addressed at the third Earth Summit held in Rio de Janeiro, 1992. One of the outcomes of the 1992 Earth Summit led to the Kyoto Protocol which sought to cut CO2 emissions in an attempt to halt global warming. An important point of contention between these two issues was, and continues to be, the tension between the Global North and the Global South on CO2 emissions. The North has traditionally hesitated to commit to binding targets on reducing carbon dioxide emissions due to fears of harming their economic competitiveness. While at the same time, much of the South was given exemptions from the Kyoto Protocol in order to facilitate their economic development. This tension remains an important obstacle to a meaningful global response to environmental issues. Since the 2000s, environmental policy has become mainstream. Environmental debates have become an important part of the elections in both the Global North and South. Government policy is increasingly critiqued through an environmental lens. Movements have globally coalesced around environmental issues, including species protection, combatting all forms of pollution, desertification, and nuclear proliferation. Perhaps the most visible environmental issue has been global climate change. The global scientific community has predominantly concluded that global warming is unequivocal and that it is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause. In response, there have been significant advancements made in environmental protection, including the creation of nature preserves on land and in the ocean, the recovery of endangered species from sea turtles to giant pandas, and organized resistance to environmental threats like Dakota Access Pipeline. Many of these achievements are either localized, requiring at most bilateral agreements, or linked to very specific causes amenable to narrow policy responses. The outstanding issue has been climate change, a more complex issue with multiple causes, variable impact, and a serious lag in cause and effect. The Paris Agreement, reached in 2015, was intended to be a significant step towards addressing climate change. However, as we will see in the following sections, its status is in doubt with US President Donald Trump’s decision to pull out of the agreement. Today, there is a wide spread recognition that environmental protection is the responsibility of us all, both individually and collectively. Individually, people are increasingly making choices based on their environmental footprint. Collectively, local and national governments are putting policy in place to achieve environmental sustainability. However, there has also been a recognition that contemporary environmental issues are global, requiring bilateral and multilateral responses. It is to global environmental governance that we turn to now.

Watch the TEDx video ‘Environmentalism, Urgency, and Seizing the Day’ by Andrew Wong:

Use the following questions to write an entry in your journal

- What is the ‘urgency’ that Andrew Wong was speaking of?

- How does his sense of urgency contrast with his view of nature as a child?

- How did the trip to the arctic activate his urgency?

- What did this motivate him to do?

- Do you have a sense of urgency?

- If so, about what?

- If not, take a minute and try to identify something that you feel is important.

- Have you acted on this sense of urgency?

- If so, what have you done?

- If not, what lessons can you draw from Andrew Wong’s talk?

There has been significant movement on addressing localized environmental issues through national regulatory bodies. There has also been significant movement on bilateral agreements and treaties that address transboundary issues. However, global environmental issues have been more difficult to deal with, in particular things considered to be part of the global commons: those resources that are owned by no one but accessible to all, like the atmosphere, the seas, and even outer space.

Figure 10-15: “Stamp” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AUsstamp-save-our.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of USPS.

Much of the reason for this is the anarchical structure of global politics, defined by the absence of an overarching authority. In other words, there is no world government responsible for the drafting and enforcement of global legislation to attenuate global environmental problems. If you remember, this is something we spoke of in detail in the module concerning political globalization. Yet these global environmental problems do exist, they are increasingly posing a threat to people around the world, and they increasingly require a multilateral response. However, while there may not be a global government, there is global governance in specific policy niches. Global governance refers to the disparate collection of norms, regimes, and institutions that enables or constrains particular behaviour at the international level. It is constituted by both formal and informal actors. Formal actors include international institutions like UN agencies as well as states which have legal personality. It also includes formal agreements like the Montreal Protocol, and regimes like the Paris Agreement. Informal actors include civil society organizations and the scientific community operating at both the national and international levels. Other informal influences include normative principles which create informal expectations of behaviour. Together, these formal and informal actors and processes guide behaviour on a number of global issues, not the least of which includes global environmental governance.

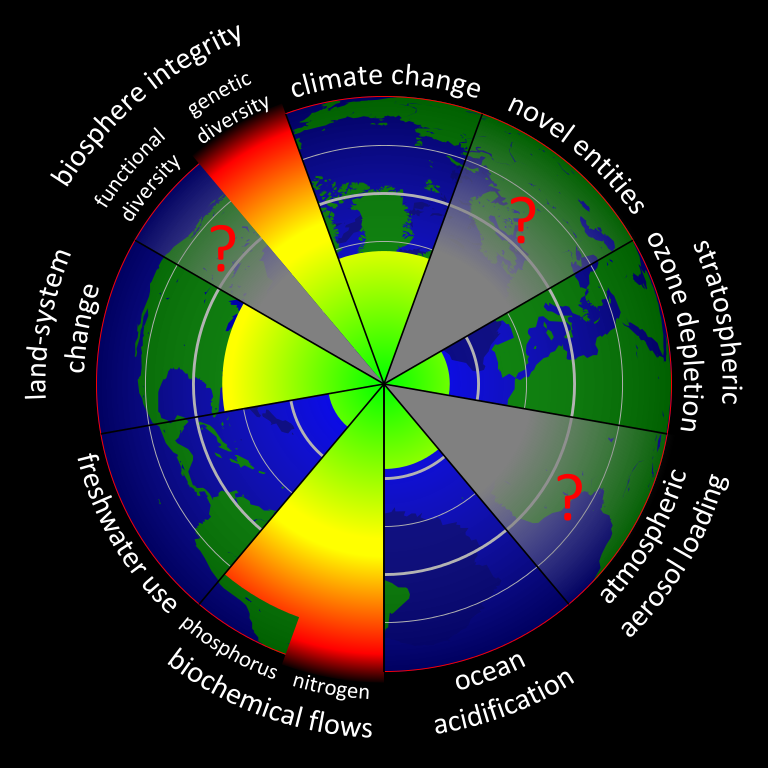

Figure 10-16: “Planetary Boundaries” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3APlanetary_Boundaries_2015.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Ninjatacoshell.

In this section, we will look specifically at governance of the global commons: the totality of actors and processes which seek to regulate behaviour that poses a threat to the global environment. For example, human action has damaged the atmosphere resulting both in specific problems, like holes in the ozone layer, and more general problems, like climate change.

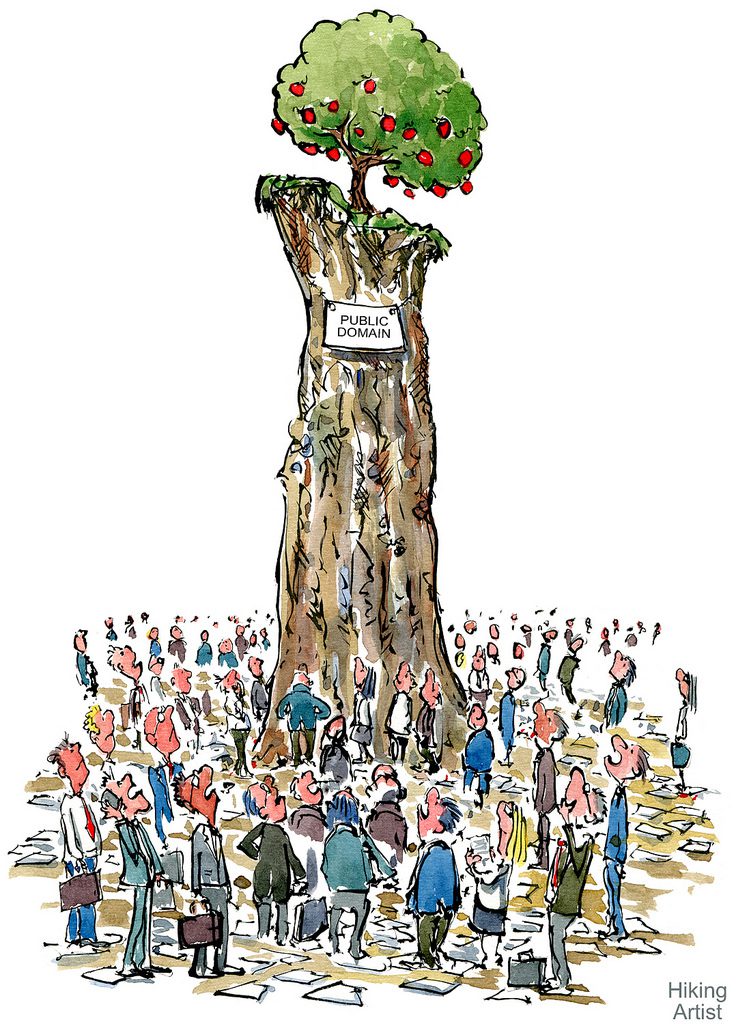

Figure 10-17: “Tragedy of the Commons” Source: https://flic.kr/p/dkd3ym Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Frits Ahlefeldt.

Both the hole in the ozone layer and changes to the climate exemplify the ‘tragedy of the commons’ at the global level, or the ‘global commons’. The ‘tragedy of the commons’ is a situation where unrestricted access to a resource that is owned by nobody, incentivizes overuse and lack of due diligence. Such resources are rapidly depleted and/or polluted.

Within the domestic realm, the ‘tragedy of commons’ can be dealt with by converting it into private property, nationalizing it, or in some way regulating it. However, the first two options are unavailable at the level of the global commons. You cannot privatize the atmosphere. You cannot nationalize the atmosphere. You can only create regimes to govern global commons such as the atmosphere.

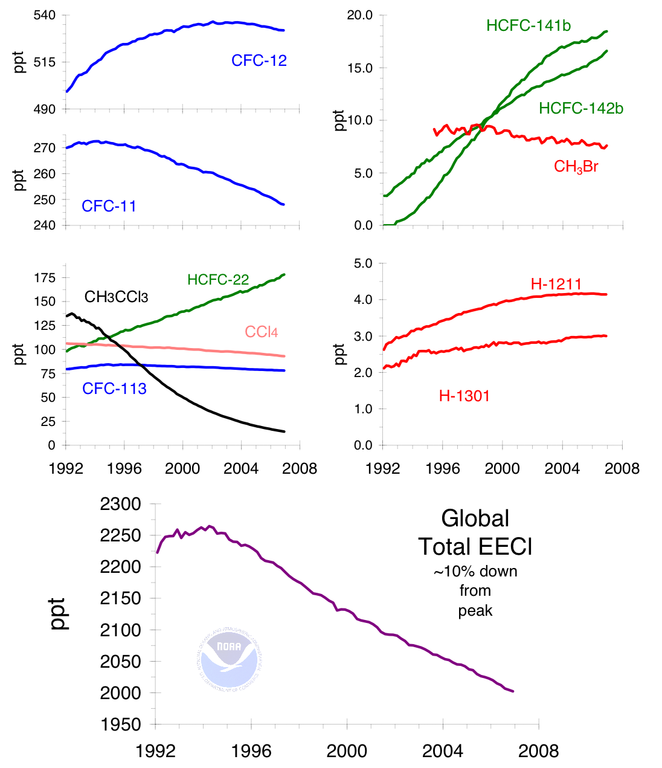

Such governance begins with the identification of an environmental threat often from an epistemic community: a global network of experts which help decision makers to both define and respond to threats. These experts largely include members of the scientific community but may also include activists and civil society organizations. These are people who are deeply invested in particular environmental issues, whether that be the ozone, ocean ecology, or deforestation. They are often the first people to become aware of problems and therefore can act as a tripwire to notify the broader population. This is very much like Carson’s book Silent Spring which alerted the general population to the damage being caused to the food chain and the threat it posed to humans. Once the epistemic community has identified a threat, their members begin to look at it, collect and share data, and try to quantify the problem. If a consensus emerges around the definition of a problem and what is needed to address it, regimes are pursued. These regimes are most often the product of interstate negotiations, the purpose of which is to create environmental policy frameworks. These policy frameworks constitute rules that seek to establish what is acceptable behaviour concerning the exploitation of the global commons. One of the most successful examples of such a regime is the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, better known as the Montreal Protocol. The Montreal Protocol started with the epistemic community noting the adverse effect of Chlorofluorocarbons on the ozone layer. Data was collected and shared, establishing this relationship. It was also noted the hazard that ozone depletion represented, specifically the increase in ultraviolet-B radiation which would lead to an increase in the incidence of skin cancer as well as harming crops and marine life. Consequently, a regime was created to phase out the production of substances identified as negatively impacting the ozone layer.

Figure 10-18: Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Montreal_Protocol#/media/File:Ozone_cfc_trends.png

Permission: Public Domain.

In order to be effective, regimes like the Montreal Protocol have to deal with the issue of compliance. It is very difficult to make sovereign states comply with international agreements since, under the condition of anarchy, there is no overarching authority to compel them to do so. States and other non-state actors have an incentive to ‘free ride’: to benefit from a collective agreement while not contributing towards it or to even operate in breach of it. Mechanisms that are used to encourage compliance range from ‘naming and shaming’ to ‘capacity building’ to incorporating international regimes into domestic law. Naming and shaming involves applying normative pressure on actors to live up to their agreements. Capacity building refers to the provision of funds, technology, expertise, and networks to achieve the desired goal of regimes. This often takes the form of commitments made by actors in the Global North to enable actors in the Global South to play a meaningful role in meeting the obligations of environmental agreements. Finally, the most powerful means to ensure compliance is when international agreements are incorporated directly into domestic law. Referring back to the Montreal Protocol, all three mechanisms are in play. Under the Montreal Protocol, there are systems of reporting and review which facilitate naming and shaming those who breach the rules. The protocol also established a multilateral fund to compensate developing economies in shifting away from the manufacture and use of CFCs. Finally, and most effectively, there has been the internalization of the Montreal Protocol by leading economies, including the US and the EU. The Montreal Protocol is an example of how global environmental governance can work. But as we will see in the next section, the lessons learned from why it was effective may be more limited than many would like to believe.

Watch “25th Anniversary Documentary – Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer”

Use the following questions to write an entry in your journal

- What are CFCs?

- Why are they problematic?

- What is the ozone and the ozone hole?

- What is the Montreal Protocol?

- Why is it considered one of the most successful international environmental agreements?

- What can be learned from the Montreal Protocol for future environmental problems?

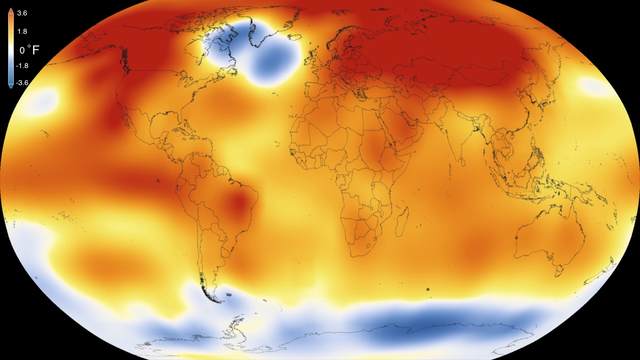

Figure 10-19: “Global temperature anomalies for 2015 compared to the 1951–1980 baseline” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:16-008-NASA-2015RecordWarmGlobalYearSince1880-20160120.png Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of NASA Scientific Visualization Studio

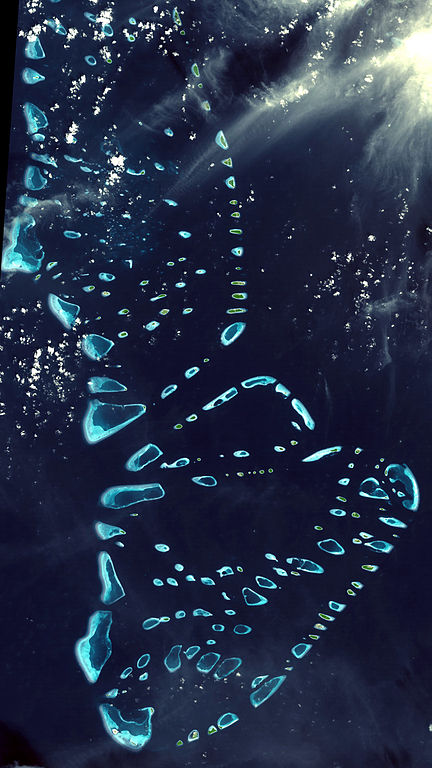

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that current trends in CO2 emissions, a powerful greenhouse gas, will result in a global temperature increase ranging between 1.4 and 5.8 degrees Celsius by the year 2100. The consequences of this temperature increase are debated but are potentially devastating, including rising sea levels, more extreme weather patterns, and a flood of environmental refugees. Take the Maldives for example, an archipelago south of India, which is the world’s lowest lying country.

Figure 10-20: “Maldives Location Map” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AMaldives_-_Location_Map_(2013)_-_MDV_-_UNOCHA.svg Permission: CC BY 3.0 Courtesy of UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

Figure 10-21: Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Malosmadulu_Atolls,_Maldives.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

The UN predicts the islands will be underwater by 2100. So what happens when an entire country sinks beneath the sea? Since 2008, the government has been investigating the possibility of buying a ‘new country’ as a contingency. In 2009, the Maldives government held an underwater cabinet meeting to draw attention to the problem of climate change. If these efforts fail, nearly 400,000 people will become climate refugees from one country alone. To mitigate such risk, the IPCC argues the global community must keep the increase of the global temperature under 2 degrees Celsius.

So far, engagement with the issue of climate change is not that different from the Montreal Protocol. Both climate change and ozone depletion are known problems. They both have identified solutions. However, here is where they part ways. The Montreal Protocol dealt with the problem of ozone depletion by banning CFCs. A simple to understand and simple to implement solution, linked to a concrete problem where alternatives were available. But stopping global temperatures from rising above 2 degrees Celsius is more complicated. Any attempt to mitigate global temperature increases will require making substantive changes to the way we live, the way we work, the way we travel, the way we shop, the way we consume, et cetera… All of which are a product of the globalization we have been discussing in this course: the technology underpinning it, the economy driving it, the culture that glorifies it, the political structure that governs it. Trying to mitigate global warming and climate change drives deep wedges into the current global order: it pits the economically developed world against the developing world and the rich against the poor. It threatens the prosperity of the wealthiest and threatens the livelihood of the poorest. Repairing the hole in the ozone layer could be solved with entrepreneurship. It could be addressed within the current global economic, political, and cultural order. Combatting climate change in any meaningful way will likely require fundamentally rethinking all of these. It will require speaking truth to power.

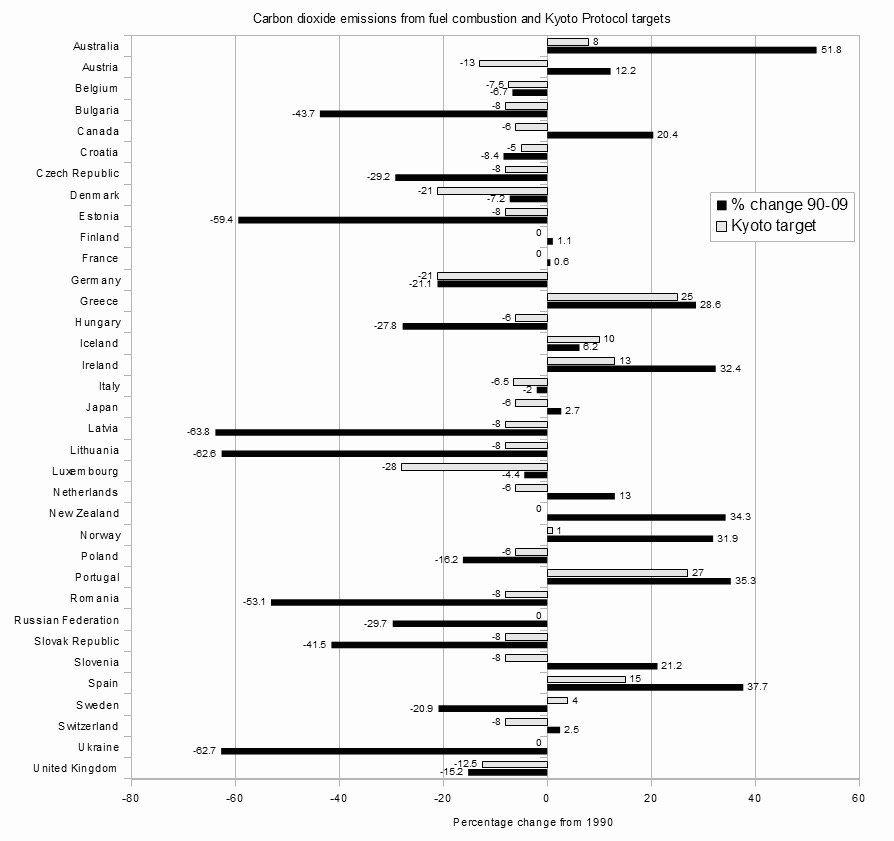

There have been efforts, mostly unsuccessful, to deal with greenhouse gas emissions, global warming, and ultimately climate change. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol committed developed economies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 5.2% below their 1990 levels by the year 2012. The primary mechanism to achieve this was through an emissions trading regime and emission offsetting arrangements. The Kyoto Protocol was criticized from the outset since major emitting countries like China and India were excluded from mandatory emissions reduction targets. This was because it was argued that climate change was a consequence of the early industrialized states and therefore they should lead efforts to cut emissions. It was also argued that they had the means to do so while many developing countries lacked the requisite resources. However, the potential costs of the Kyoto Protocol led the US to renounce it in 2001 and Canada to follow suit in 2011.

Figure 10-22: “Kyoto Parties with first period (2008–12) greenhouse gas emissions limitations targets, and the percentage change in their carbon dioxide emissions from fuel combustion between 1990 and 2009” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AKyoto_Parties_with_first_period_(2008-2012)_greenhouse_gas_emissions_limitations_targets_and_the_percentage_change_in_their_carbon_dioxide_emissions_from_fuel_combustion_between_1990_and_2009.png Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Enescot.

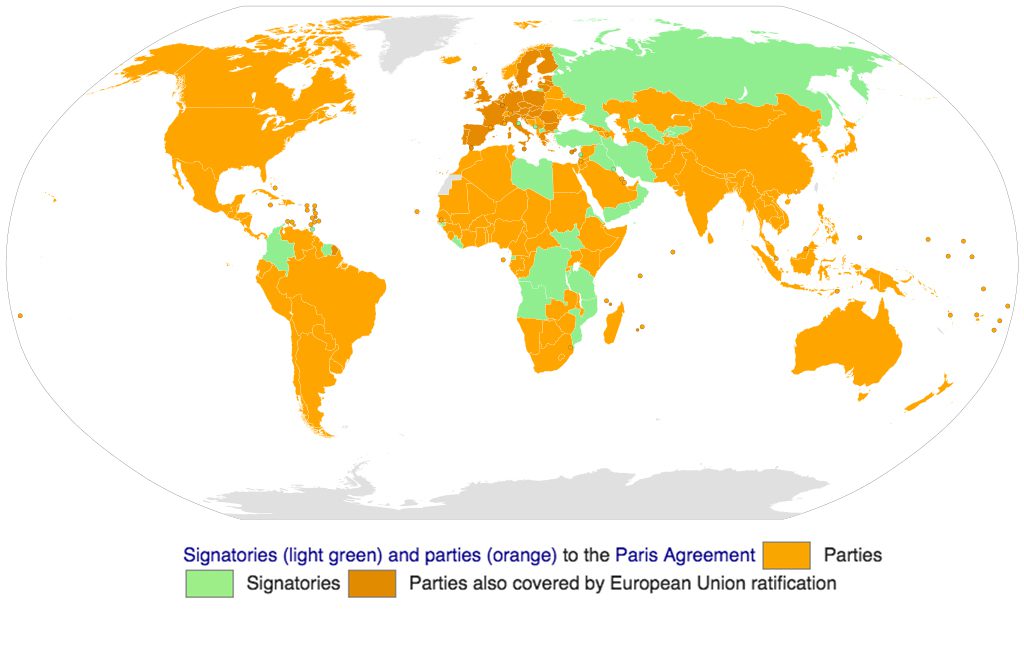

At Doha in 2012, the protocol was extended to 2020 but many important states failed to commit to a second round of emission reduction targets or they have indicated they will not/cannot meet their agreed targets. In 2015, there was a reset of sorts, with a renewed effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and contain global warming outside of the Kyoto Protocol: the Paris Agreement. This time the US and major emitting countries like China and India would be included. The agreement has 174 state parties and has been signed by 195 states in total.

Figure 10-23: “Paris Agreement” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ParisAgreement.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of L.tak.

] It takes effect in 2020 and seeks to keep the increase of global temperature below 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels by the year 2100. While parties to the agreement are able to define their own means to achieve targets, the agreement is comprehensive, seeking to ensure compliance through mitigation, adaptation, and monitoring provisions. In terms of mitigation provisions, it sets out the provisions for a global carbon market. This will allow states to buy and sell carbon assets. In terms of adaptation provisions, it enhances the capacity of states to deal with global warming by increasing resilience to new vulnerabilities. This would be at least partly realized by the establishment of a 100 billion dollar a year climate fund between 2020 and 2025. In terms of monitoring provisions, it sets out a mechanism to track state progress on their climate commitments with formalized checks every five years.

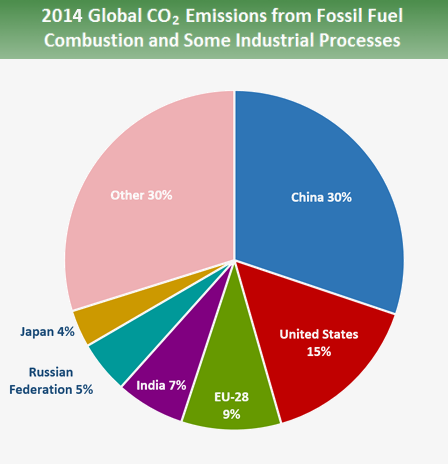

However, the agreement has also been criticized on three grounds. First, the UN Environment Program estimates that the reductions agreed to may not be enough to achieve the goal of limiting global warming to 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels. Thus, while a step in the right direction, many argue that political and economic considerations are taking precedence over the realities of climate change. Second, the agreement does not specify exact means for states to achieve their commitments. Rather each state establishes its own Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to the agreement. If they do not meet their own NDCs, the agreement does not specify any punishments for failing to achieve them. Third, and perhaps most problematic, has been the decision by the US under the Trump Administration to withdraw from the agreement. While they are not able to legally withdraw until 2020, near the end of President Trump’s term, doing so will jeopardize the agreement. The US represents 15% of global carbon commissions.

Figure 10-24: “Global Emissions 2014” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Global_emissions_country_2014.png Permission: Public Domain. Couresty of US EPA.

] It represents a significant pool of financial and entrepreneurial talent that will not be applied to climate mitigation. American withdrawal will put pressure on other states to do the same, especially trade rivals like China, Brazil, and India. Essentially, the possibility of US withdrawal threatens to unravel the agreement. Without universality, or at least having all the major emitting states on board, it will be very difficult to achieve meaningful progress on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, global warming, and climate change.

It is useful to briefly contrast the success of the Montreal Protocol with the failure of the Kyoto Protocol and the fragility of the Paris Agreement. The Montreal Protocol was successful because it identified a clear problem, proposed a relatively simple solution, and put measures in place to build capacity and ensure compliance. The Kyoto Protocol did identify a clear problem but did not propose a clear solution. Moreover, the solutions that were identified came with high costs to be disproportionately born by a few states. Finally, even if these states did meet their obligations, there was no guarantee the desired outcomes would be achieved. The Paris Agreement was more universal and did identify clearer goals. Yet is also suffers from a lack of specificity in the means to achieve them and a lack of penalties for not doing so. However, perhaps most notable, is the fragility of the agreement. If the US or another major emitting state does pull out, the pressure will be intense on other states to do the same. There will be a lot of pressure for states to withdraw from the agreement or fail to meet their NDCs since to meet these levels will require fundamental changes to every aspect of how we conceptualize modern life. And yet, failing to do so poses almost unimaginable risk.

Watch James Hansen’s TEDx talk Why I must speak out about climate change”

Use the following questions to write an entry in your journal

- Why is the issue of climate change so important to James Hansen?

- How does he counter arguments by climate change deniers?

- What does he argue the impact of climate change could be?

- If the climate change science is solid and the predictions of impact are dire, what should be done?

In this module, we have looked at the issues surrounding the global environment, the problems that are manifesting, and attempts to address them. It has been argued that the rise of industrialization, the commodification of the economy, and its spread through western institutions has resulted in environmental problems. Some of these problems are national and can be addresses domestically. Some of these problems are a bit broader, requiring bilateral responses. As we saw in ‘The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement’ of 1987, bilateral agreements are far more difficult to achieve than purely domestic solutions. Today we are facing global problems that require multilateral solutions to establish regimes of environmental governance. As we saw in the example of the Montreal Protocol as a regime to deal with ozone holes, it is possible. But as we also saw with the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, there are obstacles that we do not know how to overcome yet. The objectives of the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement require fundamental changes to our economic, political, and cultural structures. There are powerful interests working against such changes. And yet, if we do not limit greenhouse gas emissions, curb global temperature increases, and deal substantively with global climate change, there is potentially a far higher price to be paid in the future. The global community knows this; what is unknown is how to deal with it.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

1946 International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling: an international environmental agreement protecting all whale species from overhunting and a system of international regulation for whale fisheries to ensure proper conservation and development of whale stocks

Ambient global temperature: global air temperature; the overall temperature of the outdoor air that surrounds us

Bilateral: involving or affecting two parties or sides

Climate change: a change in global or regional climate patterns, in particular a change apparent from the mid to late 20th century onwards and attributed largely to the increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide produced by the use of fossil fuels

Compliance: the act of obeying an order, rule, or request

Earth Summits: United Nations conferences that began in June 1992, at which leaders of the countries gathered to discuss ways of protecting the environment

Epistemic communities: transnational network of knowledge-based experts who help decision-makers to define the problems they face, identify various policy solutions and assess the policy outcomes

‘Free ride’: a benefit obtained at another’s expense or without the usual cost or effort

Friends of the Earth: an international network of environmental organizations in 74 countries, formed to campaign for a better awareness of and response to environmental problems

Global commons: the earth's unowned natural resources, such as the oceans, the atmosphere, and space

Global environmental governance: organizations, norms, policy instruments, financing mechanisms, rules, and procedures that regulate the processes of global environmental protections

Global warming: a gradual increase in the overall temperature of the earth's atmosphere generally attributed to the greenhouse effect caused by increased levels of carbon dioxide, chlorofluorocarbons, and other pollutants

Greenhouse gases: a gas that contributes to the greenhouse effect by absorbing infrared radiation, such as carbon dioxide and chlorofluorocarbons

Greenpeace: An organization devoted to environmental activism, founded in the United States and Canada in 1971. The NGO has employed passive resistance in opposition to commercial whaling, the dumping of toxic waste into the sea, and nuclear testing

Kyoto Protocol: signed in 1997, an international treaty among industrialized nations that sets mandatory limits on greenhouse gas emissions

Montreal Protocol: signed in 1987, an international treaty designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of numerous substances that are responsible for ozone depletion

Multilateral: agreed upon or participated in by three or more parties, especially the governments of different countries

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs): part of the Paris Agreement, these refer to efforts by each country to reduce national emissions

Ozone layer: a layer in the earth's stratosphere at an altitude of about 6.2 miles (10 km) containing a high concentration of ozone, which absorbs most of the ultraviolet radiation reaching the earth from the sun

Paris Agreement: an agreement within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) dealing with greenhouse gas emissions mitigation, adaptation and finance starting in the year 2020

Planet’s carrying capacity: the maximum number of a species an environment can support indefinitely

Romanticism: a movement in the arts and literature that originated in the late 18th century, emphasizing inspiration, subjectivity, and the primacy of the individual

Sierra Club: an American environmental organization that was one of the first large-scale environmental preservation organizations

Silent Spring: written by Rachel Carson in 1962, this environmental science book documents the adverse effects on the environment of the indiscriminate use of pesticides

Sustainable development: economic development that is conducted without depletion of natural resources

‘Tragedy of the commons’: an economic problem in which every individual tries to reap the greatest benefit from a given resource. As the demand for the resource overwhelms the supply, every individual who consumes an additional unit directly harms others who can no longer enjoy the benefits.

UN Environment programme: the leading global environmental authority that sets the global environmental agenda, promotes the coherent implementation of the environmental dimension of sustainable development within the United Nations system, and serves as an authoritative advocate for the global environment

References

“A Brief History on Environmentalism.” 2 September 2015. The Green Medium. Accessed February 10, 2018, http://www.thegreenmedium.com/blog/2015/9/2/a-brief-history-on-environmentalism

Carrington, Damian. “The Maldives is the Extreme Test Case for Climate Change Action.” 26 September 2013. TheGuardian.com Accessed February 10, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/damian-carrington-blog/2013/sep/26/maldives-test-case-climate-change-action

Conca, Ken, and Oxford Scholarship Online. An Unfinished Foundation: The United Nations and Global Environmental Governance. 2015.

“How Many People can our World Support?” Population Connection. Accessed February 10, 2018, http://worldpopulationhistory.org/carrying-capacity/

Latson, Jennifer. “The Burning River that Sparked a Revolution.” 22 June 2015. Time. Accessed February 10, 2018, http://time.com/3921976/cuyahoga-fire/

Mail Foreign Service. “Maldives Government Highlights the Impact of Climate Change... by Meeting Underwater.” 20 October 2009. DailyMail.com. Accessed February 10, 2018, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1221021/Maldives-underwater-cabinet-meeting-held-highlight-impact-climate-change.html

McDonald, Charlotte. “How many Earths do we need?” 16 June 2015. BBC News. Accessed February 10, 2018, http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33133712

McGrath, Matt. “Five Effects of US Pullout from Paris Climate Deal.” 1 June 2017. BBC News. Accessed February 10, 2018, http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-40120770

Ramesh, Randeep. “Paradise Almost Lost: Maldives Seek to Buy a New Homeland.” 10 November 2008. TheGuardian.com. Accessed February 10, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2008/nov/10/maldives-climate-change

Raubenheimer, Karen and Alistair McIlgorm. "Is the Montreal Protocol a Model That Can Help Solve the Global Marine Plastic Debris Problem?" Marine Policy 81 (2017): 322-329.

Reynolds, Andy. “A Brief History of Environmentalism.” Accessed February 10, 2018, http://www.public.iastate.edu/~sws/enviro%20and%20society%20Spring%202006/HistoryofEnvironmentalism.doc

Schofield, Matthew. “When You’re Only 8 Feet Above Sea Level, Global Warming Isn’t Just an Idea.” 22 February 2016. McClatchy DC Bureau. Accessed February 10, 2018, http://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/world/article61804767.html

Swanson, Timothy M., and Robin A. Mason. "The Impact of International Environmental Agreements: The Case of the Montreal Protocol." SSRN Electronic Journal, 2002.

Tu, Yong. "Urban Debates for Climate Change after the Kyoto Protocol." Urban Studies 55, no. 1 (2018): 3-18.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. “Cuyahoga River Area of Concern” 25 October 2017. EPA. Accessed February 10, 2018, https://www.epa.gov/cuyahoga-river-aoc

Weaver, Andrew J. "Climate Change. Toward the Second Commitment Period of the Kyoto Protocol." Science (New York, N.Y.) 332, no. 6031 (2011): 795-796.

“Working Group II: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability.” 2007. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Accessed February 10, 2018, http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/tar/wg2/index.php?idp=29

Zhang Haibin, Dai Hancheng, Lai Huaxia, Wang Wentao. “U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement: Reasons, impacts, and China's response.” Advances in Climate Change Research 8, no. 4 (2017): 220-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2017.09.002

Supplementary Resources

- Speth, James Gustave., and Haas, Peter M. “Global Environmental Governance.” Foundations of Contemporary Environmental Studies. Washington: Island Press, 2006.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development. Action Against Climate Change: The Kyoto Protocol and Beyond. 1999.

- Zerefos, Christos., Contopoulos, George, Skalkeas, Gregory, and SpringerLink. Twenty Years of Ozone Decline Proceedings of the Symposium for the 20th Anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2009.

- O'Neill, Kate. The Environment and International Relations. Second ed. Themes in International Relations. 2017.