Overview

When we speak of Greenpeace, Oxfam, Amnesty International, or Doctors Without Borders, we are speaking of global civil society actors. We see these groups advocating for environmental sustainability, for reducing global inequity, for fighting political persecution, for providing life-saving medical aid in places of conflict and facing epidemics. These groups represent the ‘third sector’ of international society, a distinct category of actors in international politics. States are the ‘first sector’ of international society. As we have seen in the module discussing political globalization, states hold a privileged position in the international system and have a legal monopoly on the use of violence. They also have legal personality, allowing them to enter into binding international agreements and create international institutions. In many ways they define the frame of international politics. Multinational Corporations (MNCs) are the ‘second sector’. As we have seen in the module discussing economic globalization, Walmart is the 10th largest global economy. This demonstrates that MNCs are increasingly important actors in the international system. They use their economic might to influence the international system as framed by states. Global civil society represents the interests of the ‘people’. However, of the three sectors, global civil society is the least well defined. It is a concept that builds on the civil society literature but as extended to the global level. The term civil society is associated with ideas of democracy and representation of the citizenry. It is associated with defining and defending the interests of people against the state and corporate interests. However, doing so is more complicated at the global level, with the interests of all three sectors, but especially the third, being less clearly defined. This module will explore the concept of global civil society. It will begin with a discussion of the concept itself, looking at how it has been defined and the debates over the definitions. Next it will look at the role that global civil society has played and the context within which that role developed. Finally, it will close with a critical evaluation of the concept and role of global civil society. Before moving on, it should be noted that this discussion of global civil society is important. As we have noted throughout this course, the world is becoming more interconnected: technologically, economically, politically, and culturally. In this more interconnected world there is a need for the ‘people’ to have a voice. The question of this module: does global civil society fulfill this need?

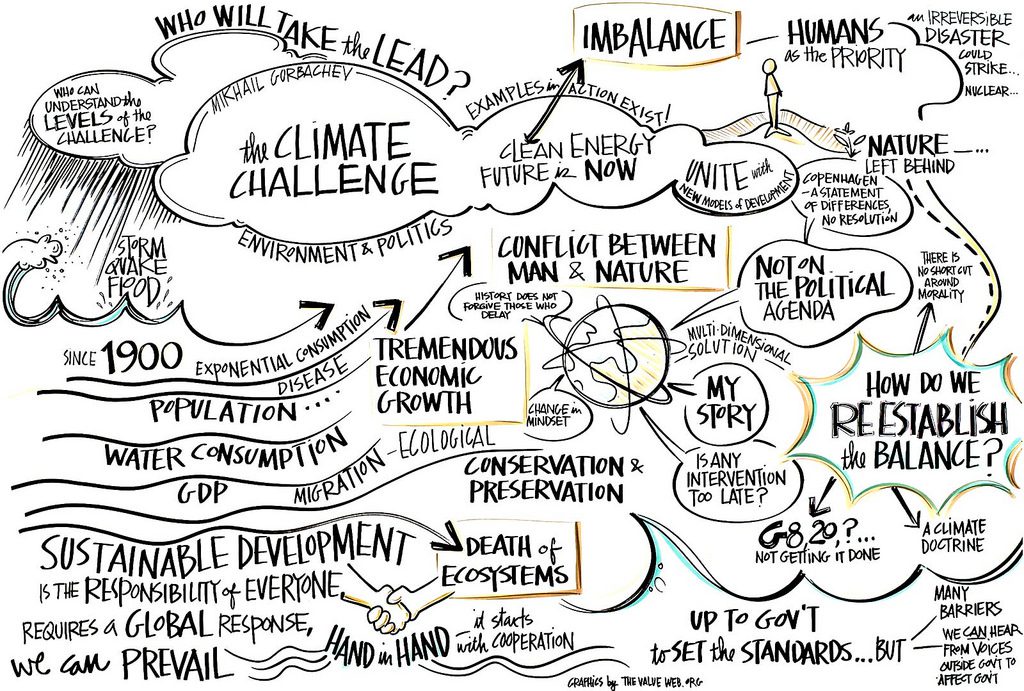

Figure 11-1: Source: https://flic.kr/p/8eBf3X Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of By The Value Web.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe the link between civil society and global civil society

- Distinguish between the three narratives of global civil society: the liberal tradition, the sociological tradition, the neoliberal tradition

- Critically assess the democratic credentials of global civil society

- Critically assess the complicity of global civil society in maintaining the structures of contemporary globalization

- Read McGlinchey, chapter two in McGlinchey

- Read Traisbach, chapter five in McGlinchey

- Take the quiz “How well do you know your NGOs? https://www.goodnet.org/articles/how-much-do-you-know-about-nonprofits-quiz

- Complete Learning Activity #1

- Read Dinyar Godreg’s article “NGOs – do they help?” https://newint.org/features/2014/12/01/ngos-keynote

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Watch “What is an NGO?” https://youtu.be/PCxJ1Ug0v6s

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Read the Economist article “Sins of secular missionaries’ economist.com/node/276931

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Amnesty International

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

- BRAC

- Civil society

- Counter hegemonic

- Dalit

- Democratic deficiency

- ‘Democratic peace theory’

- ‘First sector’

- Framing

- Freedom House

- Global civil society

- Global hegemonic order

- Greenpeace

- Liberal democratic theory

- Liberal tradition of global civil society

- Multinational Corporations (MNCs)

- Neoliberal imperialism

- Norm entrepreneurs

- Oxfam International

- Red Cross

- Responsible government

- Scottish Enlightenment

- ‘Second sector’

- Society of the Friends of Truth

- sociological perspective of global civil society

- Sovereign Military Order of Malta

- Structural Adjustment Policies

- Suffragettes

- ‘Third sector’

- World Social Forum (WSF)

- World Economic Forum (WEF)

McGlinchey, Stephen, chapter two, “Diplomacy” In International Relations, edited by Stephen McGlinchey, 20-31. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2017.

Traisbach, Knut, chapter five, “International Law” In International Relations, edited by Stephen McGlinchey, 57-70. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2017.

Learning Material

As we have seen in previous modules, the world is shrinking. We have the capacity to observe world events unfolding in almost real time: from crimes against humanity being committed in Syria or Myanmar to world events like the Olympics. We have the capacity to be anywhere in the world within hours, to work, travel, and live anywhere. Our economies are increasingly interconnected. The stock market never really closes, it just chases the clock around the world. The food we buy, the clothes we wear, and the cars we drive are increasingly the product of globalized production and multinational corporations. Our governments are increasingly aware of the actions of other states and global institutions. Politics itself has increasingly been globalized. States and the intergovernmental institutions they have created are increasingly responsible for drafting the norms, regimes, and laws that frame the modern world. But in all of this, where is democracy? Where is the voice of the people? A globalized world is by its nature multilevel. It is no longer a dyadic relationship between a state and its citizens, struggling for a balance between achieving rights/freedoms and security/order. In a globalized world, politics is operating at multiple levels; within states, between states, and at the global level; between people, states, institutions, and corporations; between ‘have’ and ‘have not’ actors. While the interests and influence of states and corporations are better understood, the role of representing the people has fallen to an under-defined concept of ‘global civil society’. For some, global civil society has filled a political role, advocating on behalf of individuals with both states and corporations. For others, global civil society is a force of resistance, fighting hegemonic actors and even ideas. And still others see global civil society as agents of these same hegemonic actors. As we will see, there is evidence to support all three assertions. In this module, we start by tracing the concept of global civil society from its domestic analog and then look at how it is understood. We will then look at how the processes of globalization have created both a need for global civil society and in turn influenced the shape it has taken. Finally, we will close with an analysis of the concept and practice of contemporary global civil society

Figure 11-2: Source: https://pixabay.com/en/smartphone-hand-photo-montage-faces-1445489/ Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of geralt.

Before moving on, let us assess your knowledge of NGOs

- Take the quiz “How well do you know your NGOs?” https://www.goodnet.org/articles/how-much-do-you-know-about-nonprofits-quiz

- Post your score on the live poll below

Before we can dig into the concept of ‘global civil society’, we need to understand how it is rooted in the discourse on ‘civil society’. The discourse on civil society has a much longer lineage in the study of politics. Aristotle mentions it in his work Politics when he refers to the shared community norms of the ‘city-state’. Socrates spoke of the importance of seeking civility in the polis. The Roman politician Cicero spoke of societas civilis, arguing that peace and order were based on the idea of a ‘good society’.

Figure 11-3: “Aristotle” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AAristotle_Altemps_Inv8575.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Ludovisi Collection.

Figure 11-4: “Socrates” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ASocrates_Louvre.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 2.5 Courtesy of Old fund.

Figure 11-5: “Cicero” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ABust_of_Cicero_(1st-cent._BC)_-_Palazzo_Nuovo_-_Musei_Capitolini_-_Rome_2016.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro.

However, these understandings of civil society differ significantly from its contemporary usage as there was little if any distinction made between the state and society. During the Scottish Enlightenment, led by thinkers like Adam Smith, civil society was linked to the role of a commercial society or the market. It was argued that commerce was a means to curb political ambition and enhance civility. Jean-Jacques Rousseau linked civil society to the institution of private property. Hegel identified the market and public law as the pillars of civil society and that such a civil society was the ethical foundation of the state.

Figure 11-6: “Adam Smith” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AAdam_Smith_The_Muir_portrait.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of J.H. Romanes 1945.

Figure 11-7: “Jean-Jacques Rousseau” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AJean-Jacques_Rousseau_(painted_portrait).jpg Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 11-8: “Georg Wilhelm Friedrich” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGeorg_Wilhelm_Friedrich_Hegel00.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

However, this understanding of civil society also differs significantly from its contemporary usage as there was little if any distinction made between the market and society. In its contemporary usage, civil society is posited to reside somewhere between the state and the market. It is a social space where the capacity to form a collective voice resides. This literature came into prominence in the post-1989 discussions on democratic transitions of the former Soviet states. It was used to describe those resources mobilized to offer alternatives to a state-controlled society. Nowadays, civil society is often used interchangeably with non-governmental organization, non-profit organization, or community organization. These are autonomous actors constituted largely by volunteers who seek to advance particular interests, values, or identities. They operate in the public sphere on issues such as environmental protection, women’s rights, or reducing inequality. They seek to raise awareness in the general public, apply pressure on stakeholders, and ultimately influence formal governmental policy.

Global civil society holds many of the same traits as their domestic counterparts. These actors reside in the space between governments, commercial actors, and multinational corporations. They are often seeking to influence governments, MNCs, and institutions to address global issues they believe to be important. However, there are also significant differences between the two as well. Civil society groups operate in a bounded social space constituted by itself, the government, and commercial actors. They have a shared history, norms, values, and identities. While they may disagree on policy or goals, they share a common frame to debate them and they operate within a fixed legal framework. Global civil society groups often lack these common frames and operate in an anarchical framework constituted by multiple groups, on multiple levels, with divergent interests. Some global civil society groups are based in developed states, many acting in support of contemporary processes of globalization even if trying to mitigate some of the excess globalization produces. Others are based in developing states and often seek to challenge that status quo. Both groups are interacting with states and MNCs of various capabilities, identities, and interests. The scope of what counts as global civil society and the lack of structural constraints has led to variance in how the concept is understood.

Figure 11-9: “Democracy!” Source: https://flic.kr/p/aPq1Ka Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Judit Klein.

From the literature on global civil society, three traditions or narratives have been identified. The first is the liberal tradition of global civil society, rooted in liberal democratic theory. Global civil society from this perspective seeks to foster western political norms. These norms include a representative and responsible government, an independent judiciary, a respect for human rights, and an open, unbiased media. They often use terms like ‘democratic accountability’, ‘good governance’, or ‘rule of law’. It is argued that the strength of civic institutions and the quality of political society are fundamental to creating and maintaining stable states. From this perspective, it is posited that global civil society acts as a counterpoint to both corrupt or weak government and rapacious multinational corporations. Moreover, as states become more democratic, they join the liberal zone of peace which is also known as ‘democratic peace theory’: that democratic states do not go to war with other democratic states. Thus, global civil society is not only contributing to stable and just states but they are contributing to a more peaceful international system.

A good example of a global civil society organization in this tradition is Freedom House. According to its website, it “is an independent watchdog organization dedicated to the expansion of freedom and democracy around the world.” It one of the oldest such organizations, founded in 1941. It produces three reports, ‘Freedom of the Press’, ‘Freedom of the Net’, and most importantly, ‘Freedom in the World’. This last report, ‘Freedom in the World’, is an annual survey which ranks states as ‘free’, ‘partly free’, or ‘not free’ based on a score which combines assessment of political rights and civil liberties. The NGO also participates actively in advocacy initiatives to promote democracy around the world. There are criticisms of Freedom house, particularly for their connections to the US and most notably the State Department. It has been accused by the Cuban, Iranian, Sudanese, and Uzbek governments as acting as a cover for US interests.

Figure 11-10: “Freedom House” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AFreedom_house_freedom_of_the_world_2018_map.png Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Delfadoriscool.

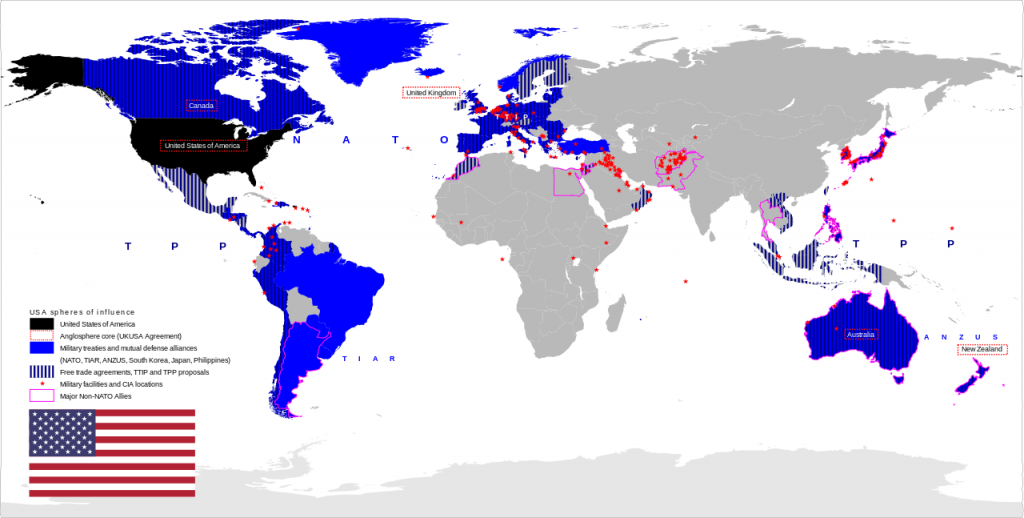

The second tradition comes from a sociological perspective of global civil society. In this narrative, global civil society is seen as a source of popular resistance to both authoritarian states and to class-based institutions and actors, including multinational corporations. As such, there is some overlap with the liberal tradition. Both see global civil society as standing between states and corporations. However, the liberal tradition seeks to reinforce the global hegemonic order based on the principles of liberal democratic norms. The sociological tradition seeks to challenge the hegemonic order, both politically and perhaps more importantly economically. It seeks to challenge political and economic structures which reinforce and thus perpetuate inequity and inequality; for example, the overwhelming influence of American and European states in the International Financial Institutions (IFIs) through representation and weighted voting. Or the ability of large MNCs to overwhelm the regulatory and legislative capacity of smaller states.

Figure 11-11: “US Empire” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:USempire.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Nagihuin.

Figure 11-12: “Brands” Source: https://flic.kr/p/bBRLcy Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of Brett Jordan.

In this way, the sociological position incorporates more radical ideologies and is deeply motivated to seek changes in both domestic and international structures. An example of this counter-hegemonic advocacy can be seen in the World Social Forum (WSF) whose tagline is “another world is possible’.

Figure 11-13: “World Social Forum” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AWorld-Social-Forum.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of merlin.

The WSF met for the first time in 2001 and organized in opposition to the World Economic Forum (WEF).

Figure 11-14: “World Economic Forum” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:World_Economic_Forum_logo.svg Permission: Public Domain.

The WEF is a meeting of the world’s most powerful people, economically, politically, and culturally. Its mandate, according to its website, is to “engage the foremost political, business and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas.” It is by definition an actor seeking to reinforce the hegemonic economic and political norms of the contemporary world. The WSF argues the WEF is a leader of the neoliberal order we discussed in module 3. It seeks to organize advocacy groups, NGOs, and social movements who oppose this neoliberal order. It consciously seeks to build networks between these groups to foster solidarity amongst them and enable coordination of global campaigns. It is by definition counter hegemonic. Critics of the WSF point to its decentralized structure which many argue limit its effectiveness and the overwhelming representation of middle/upper class white members from the Global North compared to voices emanating from the Global South.

The third tradition argues global civil society is an intrinsic part of the processes of globalization. This narrative took on increased saliency in the 1980s and 1990s in response to the rise of neoliberalism. As we discussed in the module on economic globalization, the orthodoxy of neoliberalism put pressure on states to deregulate, privatize, and adhere to market discipline both by cutting expenditures and opening their domestic markets to international competition. States in the Global South were coerced into adopting these policies through the Structural Adjustment Policies of the IFIs.

Figure 11-15: “The World Bank” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AThe_World_Bank_logo.svg Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 11-16: “International Monetary Fund” Source: https://flic.kr/p/pbFR2T Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Global Panorama.

Global civil society actors have attempted to fill the void left by the retreat of the state. NGOs have become providers of social services, health care and education. They have become the defenders of the oppressed, advocating on their behalf in domestic courts and to local governments while at the same time appealing to support from international actors. They play the role of witness, to describe to the world the inequity rampant in many corners of the world. For many people, this role and these actions are framed as virtuous. However, the pursuit of such virtuous goals requires funding. States, both in the Global South but more often in the Global North, are a convenient source for such funds as are MNCs. States and MNCs have an interest in fostering such relationships as global civil society actors can provide greater legitimacy to their actions. They improve the brand image of MNCs. They open doors with local communities, allowing access to resources and partners. In some cases, this relationship is explicit, with NGOs being set up directly by a state or MNC. In others, there may be an intention on the part of the NGO to maintain their independence. But despite even the best of such intentions, funders can and do exert influence on recipients. From this perspective, global civil society is facilitating the processes of economic and political globalization.

Figure 11-17: “Recep Tayyip Erdoğan” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ARecep_Tayyip_Erdogan_2017.jpg Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of US Department of State.

For example, there has been an interesting investigation into the ability of both domestic and global civil society actors to operate in contemporary Turkey under the increasingly illiberal government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

These are organizations that seek to operate independently of the state. However, in order for to operate in Turkey, they need the permission of the government. Once permission has been given, investments are made by NGOs. If the government does not like the direction of programming, they can rescind their permission and deny them access. These groups are thus slowly co-opted and begin working with the state instead of acting as a watchdog against them. These three perspectives on global civil society have vastly different views on definition and practice. However, before we can critically assess global civil society, we need to turn to its historical development. This is the topic of the next section.

Read Dinyar Godreg’s article “NGOs – do they help?” https://newint.org/features/2014/12/01/ngos-keynote

Use the following questions to write an entry in your journal

- Why does the article question of the altruism of NGOs?

- How are they coopted? By whom?

- What are NGOs good at?

- Where are NGOs failing?

- What does the article suggest NGOs should do?

In order to understand the debates that surround contemporary global civil society, it is important to examine how they have come to play such a prominent role in the processes of globalization. Global civil society has had a long history. Prior to the modern age, civil society was constituted by religious orders, merchant guilds, and scientists. Many of these still exist today.

Figure 11-18: “Coat of Arms of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ACoat_of_arms_of_the_Sovereign_Military_Order_of_Malta_(variant).svg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Mathieu CHAINE.

Consider the Sovereign Military Order of Malta which was founded in 1048. It is currently carrying out social care and humanitarian aid in 120 states.

In the 18th century, many of these groups became more organized and international in form. Some were revolutionary in character, like the Society of the Friends of Truth which acted as a means to connect leading revolutionary scholars across Europe. Others focused on human rights, like the abolitionist movements which sought to ban slavery. Groups advocating for women’s right to vote, like the suffragettes, are other examples. However, probably one of the most famous of these early non-governmental organizations was the Red Cross, founded by Henri Dunant in the 1860s after witnessing the atrocities of the Battle Solferino. He saw the wounded soldiers left to die on the battlefield, essentially treated as cannon fodder, and sought to create change.

Figure 11-19: “Battle of Solferino” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Battle_of_Solferino,_1859.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Levin01.

Other wars generated new actors: Save the Children emerged from the First World War and Oxfam emerged from Second World War. While these organizations and movements were influential, and some continue to be, their numbers and resources were miniscule compared to today. Right now, there are over 20,000 international non-governmental organizations. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has an endowment of 28.8 billion US dollars. BRAC, an international development organization in Bangladesh, has a staff of 120,000.

Figure 11-20: “Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ABill_%26_Melinda_Gates_Foundation_logo.svg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Source: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Figure 11-21: “BRAC logo” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ABRAC_logo.png Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Camille JOLIVET.

This quantum growth in the number and size of global civil society actors can largely be traced to the 1980s. As introduced earlier, in the 1980s neoliberal policies were enforced by the IFIs through Structural Adjustment Programs. This led to a retreat of the state from the provision in public services and representation of societal interests. NGOs partially filled the void that this retreat created. They began to fill niches on human rights, the environment, women’s rights, labour, et cetera. Global civil society is thus a product of the processes of globalization and in turn has used these processes to multiply.

The range of groups counted amongst global civil society, while in many ways divergent, all share a similar path of mobilization. First, they act as norm entrepreneurs, presenting the issues they deem important as problems that require urgent attention. The ultimate goal is to undermine current practices, or norms, and replace them with new practices/norms. For example, Henri Dunant conveyed what he witnessed on the battlefield at Solferino. He argued that wounded soldiers needed rights and protection. Dunant’s advocacy ultimately resulted in formation of the International Committee of the Red Cross and establishment of the Geneva Conventions, establishing new norms which inform new practices.

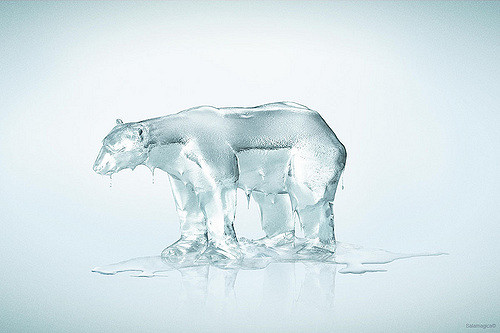

Framing is an important means to accomplish this. An ideational frame acts just a like a picture frame; it sets the context of an issue and draws the audience towards what they want you to believe is important. Think of images of starving polar bears used as a frame to advocate for changes to environmental norms.

Figure 11-22: “Endangered Arctic” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Endangered_arctic_-_starving_polar_bear.jpg Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Andreas Weith.

Second, these global civil society actors operationalize this knowledge through the frames they have created. They create campaigns to raise public awareness or organize protests; for example, the World Wildlife Federation campaign to combat global warming using the image of a melting polar bear or the campaign to combat deforestation using an image of the forest in the shape of a pair of lungs.

Figure 11-23: “WWF” Source: https://flic.kr/p/73xvQ6 Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of salamagica.

They seek to make their issue, whether it be the environment or human rights, a part of the public discourse on a global scale. They make the issue political, requiring political solutions both domestically and internationally. For example, Amnesty International documents human rights issues in 159 countries and has consultative status at the UN. They specifically raise awareness about political prisoners and conduct letter campaigns to highlight their plight.

Figure 11-24: “Amnesty International Torture Cell 053” Source: https://flic.kr/p/4SCxNF Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Cheryl Biren.

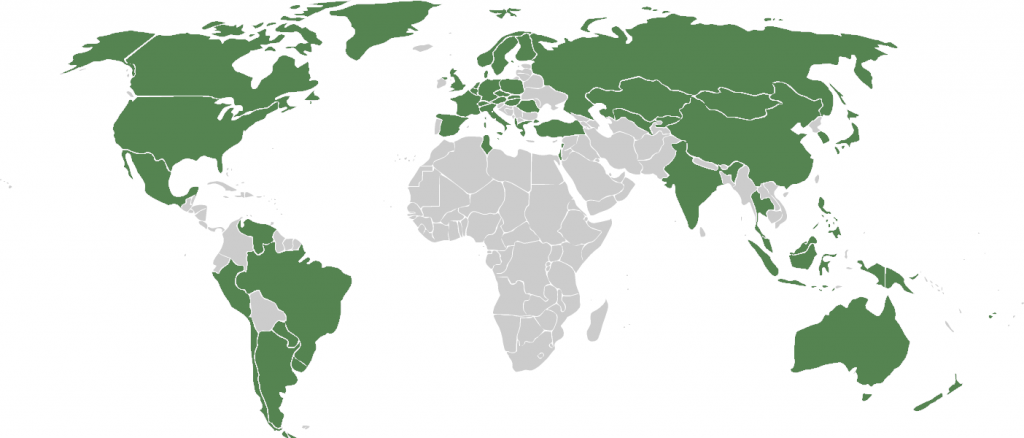

Third, global civil society seeks recognition as the legitimate representative of their cause. They want to be seen as the face of the issue. The most effective means to stake a claim of representation is to have a large transnational membership and to control access to influential networks. For example, Greenpeace has approximately 2.8 million members and 26 offices covering 55 states.

Figure 11-25: “Green Peace” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGreenpeace_paises.PNG Permission: CC BY-SA 2.5 Courtesy of Tappoz.

Such a member base gives Greenpeace power. They can call upon their base for resources. They can mobilize their base for protests. They can ask their base to contact their elected representatives and apply pressure on governments. This path of mobilization has led to global civil society both greatly expanding and playing an increasingly significant role in globalization.

Watch “What is an NGO?”

Use the following questions to write an entry in your journal

- What are the 3000 NGOs doing in Afghanistan?

- How do they describe their mission?

- What must NGOs do to operate in conflict zones?

- Why is community acceptance important?

- What can put NGO workers at risk?

As we have seen, global civil society has become an increasingly visible and powerful actor in international affairs. We also saw that its role is contested. Some see the role as promoting democracy, others a repository of resistance, and still others as an embedded component of globalization itself. We have also seen global civil society have its own narrative. It frames itself as being constituted by altruistic saviours, dedicating their time and putting their lives on the line to defend human rights and promote democracy. However, there are also two serious critiques of global civil society. First, it is argued that global civil society has a serious democratic deficiency. Second, it is argued that global civil society is simply a band-aid solution that masks its complicity in the project of neoliberal imperialism.

The first critique of global civil society centres on its democratic credentials. As we saw in the previous section, global civil society actors often seek to be the face of particular issues, like Greenpeace does for the environment or Amnesty for political prisoners. We also saw that they seek to build a large membership base and transnational networks. This membership and these networks not only give NGOs influence, but they also enable the claim that they are the voice of the people. Either explicitly or implicitly, they claim to be the democratic solution to the problem of global politics. They claim to represent the Dalit, or ‘untouchables’, in India, the miners or agricultural laborers in Latin America, or political prisoners around the world.

Figure 11-26: “School of untouchables near Bangalore” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AA_school_of_untouchables_near_Bangalore_by_Lady_Ottoline_Morrell_2.jpg Permission: Public Domain.

In so doing, global civil society is claiming to be the ‘third sector’, the voice of the people, contending with states and MNCs. But who has given them this right? Have the Dalit consented to representation by global civil society actors? Is there a democratic mechanism to determine which global civil society actor gets to claim such representation? What about the democratic credentials of the NGO organizations themselves? How are decisions made in Greenpeace? Who gets to set the agenda? How are resources deployed? There is no definitive nor effective framework to establish the democratic credentials of global civil society actors. These are deeply problematic questions if global civil society seeks to claim any sort of meaningful representation at the global level.

The second critique of global civil society is that it only offers a band-aid solution to systemic problems. It addresses the worst excesses of the global order but does not fundamentally solve problems of poverty, inequity, democratic representation, and human rights violations.

Figure 11-27: “OXFAM” Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AOxfam_italia.JPG Permission: Public Domain.

This may seem to contradict lofty mission statements like Oxfam International who state they seek “To create lasting solutions to poverty, hunger, and social injustice”. While Oxfam has been operating since 1942, I am not certain they have achieved any of these goals.

However, it is possible to understand the lack of systemic change affected by global civil society if we consider them as complicit in supporting the neoliberal processes of economic, political, and cultural globalization. To be clear, it is not argued that these global civil society actors are necessarily corrupt or acting against the interests of those they are trying to help. Quite to the contrary; the good that they do is often recognized. But it is argued that this ‘good’ doesn’t achieve structural change; rather it merely makes the system more palatable by reducing its worst excesses. Many who might radicalize or seek to overturn the status quo are placated by the evidence of ‘progress’. They see groups advocating on their behalf, seeking to redress inequity, and fighting for human rights. Yet at the same time, global elites are amassing record levels of wealth. Take for instance the Oxfam report which argues 8 people have the cumulative wealth of half the world’s population. From this perspective, while NGOs may seek to do good, they embody the norms of the hegemonic elite. They support specific norms that underpin contemporary economic and political structures, such as individual rights, private property, and the efficacy of the market. They support hegemonic cultural norms that give legitimacy to these economic and political structures, norms around democracy and capitalism. Thus, while being a positive force in the world, this narrative of global civil society sees its role as essentially being the good cop to the bad cop role being played by states and MNCs. Together, the good cop/bad cop work to maintain the status quo. Both critiques, that of democratic deficiency and that of being complicit in the neoliberal order, are substantial. They indicate that while global civil society is an increasingly important part of the international order, its intent and impact is less certain.

Read the Economist article “Sins of secular missionaries’ economist.com/node/276931

Use the following questions to write an entry in your journal

- What is the connection between NGOs and states?

- Why is the revolving door between NGOs and states instructive?

- What is the connection between NGOs and the UN?

- What is the connection between NGOs and private donors?

- As NGOs get larger, how do they come to look more like MNCs?

- Assess the comment: ‘The chief aim of NGOs should be their own abolition’

Figure 11-28: “Super Blue 2012” Source: https://flic.kr/p/bEUa23 CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of jason jenkins.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Amnesty International - commonly known as Amnesty or AI, Amnesty International is a London-based non-governmental organization focused working against human rights violations and for the release of persons imprisoned for political or religious dissent.

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – a private foundation founded by Bill and Melinda Gates, said to be the largest private foundation in the US that focuses on global health initiatives, global development initiatives, sustainable economic growth, and improving US high school and post secondary education, among others.

BRAC – an NGO, social enterprise, policy advocate network that was founded in Bangladesh, bringing together activists and changemakers.

Civil society – a community of non-governmental organizations and institutions that manifest the interests and will of citizens.

Counter hegemonic – a social movement that challenges the status quo.

Dalit - a member of the lowest caste in the traditional Indian caste system.

Democratic deficiency – when there is believed to be a lack of democratic accountability and in democratic organizations or institutions.

‘Democratic peace theory’ – emerged from Immanuel Kant’s essay “On Perpetual Peace,” the theory posits that democracies are hesitant to engage in armed conflict with other democracies.

‘First sector’ – in international society, states make up the ‘first sector.’ States hold a legal monopoly on the use of violence and they have a legal personality, allowing them to enter into binding international agreements and create international institutions.

Framing - a set of concepts and theoretical perspectives on how individuals, groups, and societies, organize, perceive, and communicate about reality.

Freedom House – a US-based NGO that analyzes the challenges to freedom, advocates for greater political rights and civil liberties, and supports activists to defend human rights and promote democratic change.

Global civil society - refers to the vast assemblage of groups operating across borders and beyond the reach of governments.

Global hegemonic order – a system created by a hegemon to maintain its dominant position through institutions which are hard to change and more convenient to continue using them than revamp. These institutions tend to favor the hegemon, but provide protection and a stable world order for the rest of the world.

Greenpeace – NGO devoted to environmental activism, founded in the United States and Canada in 1971. It has employed passive resistance in opposition to commercial whaling, the dumping of toxic waste into the sea, and nuclear testing.

Liberal democratic theory – a democratic system in which individual rights and freedoms are officially recognized and protected, and the exercise of political power is limited by the rule of law.

Liberal tradition of global civil society – sees the actor as providing a bottom-up contribution to the effectiveness and legitimacy of the international system as a whole; power is being held to account by the populace.

Multinational Corporations (MNCs) - an enterprise operating in several countries but managed from one (home) country.

Neoliberal imperialism – the spread of neoliberal ideas, including neoliberal globalization, through diplomatic means.

Norm entrepreneurs - individuals, NGOs, states or international organizations which

actively promote a norm and seek initial acceptance for the norm.

Oxfam International – (“Oxford Committee for Famine Relief”) an international organization established in England in 1942 to provide training and financial aid to people in developing countries and disaster areas.

Red Cross - an international philanthropic organization formed in consequence of the Geneva Convention of 1864, to care for the sick and wounded in war, secure neutrality of nurses, hospitals, etc., and help relieve suffering caused by pestilence, floods, fires, and other calamities.

Responsible government - refers to a government that is responsible to the people. For example, in Canada it is more commonly described as an executive that is dependent on the support of an elected assembly, rather than on the monarch.

Scottish Enlightenment - the period in 18th and early 19th century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of scientific and intellectual accomplishments.

‘Second sector’ – in international society, multinational corporations make up the ‘second sector,’ and are increasingly important actors.

Society of the Friends of Truth – French revolutionary organization that connected scholars from across Europe to formulate political theories.

Sociological perspective of global civil society - global civil society is seen as a source of resistance to both authoritarian states and to class-based institutions and actors, including multinational corporations by challenging political and economic structures which perpetuate inequality.

Sovereign Military Order of Malta - a Roman Catholic lay religious order traditionally of military, chivalrous and noble nature. Widely considered a sovereign subject of international law, the order maintains diplomatic relations with more than 100 states.

Structural Adjustment Policies - a set of economic policies often introduced as a condition for gaining a loan from the IMF, usually involving a combination of free-market policies such as privatization, fiscal austerity, free trade and deregulation. They have been controversial with detractors arguing the policies are often unsuitable for developing economies and lead to lower economic growth and greater inequality.

Suffragettes – women seeking the right to vote through organized protest.

‘Third sector’ – refers to global civil society, distinct from government and business sectors.

World Social Forum (WSF) - an annual meeting of civil society organizations, first held in Brazil, which offers a self-conscious effort to develop an alternative future through the championing of counter-hegemonic globalization.

World Economic Forum (WEF) - an independent non-profit organisation dedicated to improving global economic and social conditions on a global scale. It is well known for its annual meeting held in January in Davos, Switzerland.

References

Calhoun, Craig (Ed.). Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. Accessed February 18, 2018, http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195123715.001.0001/acref-9780195123715-e-262

Castel, John. “Greenpeace at War.” 11 October 2005. Independent.co.uk. Accessed February 18, 2018, http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/greenpeace-at-war-318919.html

“Civil Society.” 2018. World Economic Forum. Accessed February 18, 2018, https://www.weforum.org/communities/civil-society

“Dalit Solidarity Network UK.” Accessed February 18, 2018, http://dsnuk.org/

Davies, Thomas. “NGOS: A Long and Turbulent History.” 24 January 2013. The Global Journal. Accessed February 18, 2018, http://www.theglobaljournal.net/article/view/981/

Doyle, Jessica. “Between Control and Co-option: The Future of Civil Society in Erdoğan’s Turkey.” 14 June, 2016. NGO Advisor. Accessed February 18, 2018, https://www.ngoadvisor.net/csos-erdogan-turkey-doyle/

Fisher, William F. "Doing Good? The Politics and Antipolitics of NGO Practices." Annual Review of Anthropology 26 (1997): 439-64

Freedom House. 2017. “Freedom House.” Accessed February 18, 2018, https://freedomhouse.org/

Hall-Jones, Peter. “The Rise and Rise of NGOS.” May 2006. Global Policy Forum. Accessed February 18, 2018, https://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/176/31937.html

Krieger, Joel (Ed.). The Oxford Companion to Politics of the World (2nd ed.) Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Accessed February 18, 2018, http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195117394.001.0001/acref-9780195117394-e-0128

Macdonald, Lisa. “What’s Happened to Greenpeace?” 30 April 1997. Green Left Weekly. Accessed February 18, 2018, https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/whats-happened-greenpeace

Noh, Jae-Eun. “The Role of NGOs in Building CSR Discourse around Human Rights in Developing Countries.” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies 9, no. 1 (March 2017): 1-19.

Paul, James A. “NGOs and Global Policy-Making.” June 2000. Global Policy Forum. Accessed February 18, 2018, https://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/177/31611.html

“The 14 Most Influential Sustainability NGOs.” 1 July 2014. Sustainability Degrees. Accessed February 18, 2018, https://www.sustainabilitydegrees.com/blog/most-influential-sustainability-ngos/

United Nations. “Civil Society.” Accessed February 18, 2018, http://www.un.org/en/sections/resources-different-audiences/civil-society/

“What is Civil Society?” 5 July 2001. BBC World Service. Accessed February 18, 2018, http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/people/highlights/010705_civil.shtml

Supplementary Resources

- Baur, Dorothea., and SpringerLink. NGOs as Legitimate Partners of Corporations A Political Conceptualization. Issues in Business Ethics, 36. 2012

- Kamat, Sangeeta. "The Privatization of Public Interest: Theorizing NGO Discourse in a Neoliberal Era." Review of International Political Economy 11, no. 1 (2004): 155-76

- Keane, John. Global Civil Society? Cambridge University Press. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Steffek, Jens., and Hahn, Kristina. Evaluating Transnational NGOs: Legitimacy, Accountability, Representation. Houndmills, Balsingstoke, Hampshire [England]; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.