Overview

In module one, we examined the different aspects of the Canadian narrative. We examined the dominant story of Canada as an inclusive and multicultural state domestically and as a human rights champion abroad. We questioned this narrative with some darker examples of Canadian history and some contemporary issues of equity. The purpose of this interrogation was to demonstrate the need to understand and be critically aware of questions of justice. In this module, we turn to the interrogation of the concept of justice itself as examined through our text “Justice: what’s the right thing to do?” by Michael Sandel.

Figure 2-1: "Michael Sandel" Source Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0 Courtesy of Akshaysinha100.

In this module, we will introduce and problematize the concept of justice. As we introduced in module one, most people have an intuitive understanding of justice. It is related to ideas of fairness and equality. It is understood to be a necessary, if perhaps an insufficient cause, of a ‘good society’. However, people understand both justice and injustice differently. Sandel suggests that the three dominant strains of justice revolve around the concepts of welfare, freedom, and virtue. We will discuss these three conceptions of justice and the ideological approaches that seek to give rigour to them. The purpose here is to introduce these perspectives in a comparative fashion. This will establish the basic framework for the remainder of the course to discuss and problematize the concept of justice. From this comparative framework, we will delve much deeper into each perspective in subsequent modules. Ultimately, at both the end of the book and at the end of this course, we will bring the discussion of justice back to the questions how this informs our understanding of the common good, and what this means to understanding the narrative of Canada. Finally, the last goal of this module will be to introduce the value of looking at Justice through the heuristic of moral dilemmas. Moral dilemmas force us to confront what we believe to be true, right, moral, and just. They intentionally put our convictions to the test, pushing us into dialectic reasoning between our principles and hard cases. In finding a synthesis between them, we are better able to understand and pursue justice both individually and collectively. This will allow us to better define the good life.

Figure 2-2: "What is the good life?" Source Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Quinn Dombrowkski.

- Debate the meaning of justice

- Contrast the three approaches to justice: utility, freedom, and virtue

- Apply the concept of ‘moral dilemma’ as a means to define and seek out justice in politics and law

- Read Sandel’s Justice Chapter 1

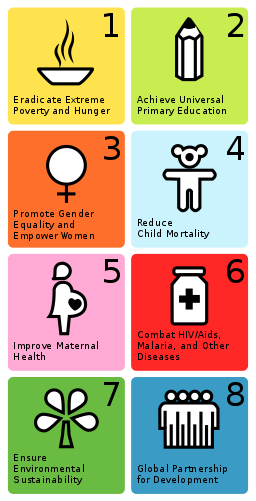

- Take the “Are you an Activist’ Quiz: Become a factivist! (globalgoals.org)

- Complete learning activity #1

- Watch the CBC News video “Bill 62: How Québec’s face-covering ban will work” https://youtu.be/b90FvQdj3v8

- Watch the Global News video “Exclusive Ipsos poll reveals support for Bill 62 highest in Quebec” https://globalnews.ca/video/rd/1083357763711/

- Complete learning activity #2

- Read the BBC Ethics Primer on The Ticking Time Bomb Scenario http://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/torture/ethics/tickingbomb_1.shtml

- Complete learning activity #3

- Watch the trailer for “The Fruit Machine” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-GJpLSGzGgo

- Complete Learning activity #4

- Burqa/Niqab

- Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- Individual Freedom

- Moral dilemmas

- Price gouging

- Pride events

- The ‘fruit machine’

- Virtue

- Welfare

Michael Sandel, Justice “Doing the Right Thing” pg. 3-30 [Textbook]

Learning Material

The purpose of this module is to interrogate the concept of justice. To ask how justice is understood differently and the implications of those differences. It seeks to ground this debate in different philosophical traditions. In so doing, we will be providing rigour to our discussion of the question at the heart of this class: How should a society be organized and governed? In other words, by understanding justice, we are able to better discuss and question contemporary forms of social organization, including the state, politics, and law. In the process, you will be asked to question your own definition of justice and the values that you hold individually as well as the values we espouse collectively. This will provide a theoretical framework for this course which will be applied to the social construct of Canada as introduced in module one.

To this end, this module we will look at the concept of justice and why it is so contested. All claims of justice stake a claim on what is right, fair or equitable. But righteousness, fairness, and equity are not universally held ideas. Are they based on the rights of the individual? Are they defined by the values held by the majority within a particular society? Are they contextual, defined in relation to the person or group in question? Do the ends justify the means even if that requires sacrificing the innocent? Do numbers matter? Is the sacrificing of one innocent life ‘just’ if it saves two innocent lives? Twenty innocent lives? Two hundred innocent lives?

Figure 2-3: “Thinker” Source Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Backdoor survival.

These are the tough questions that will allow us to interrogate our beliefs in a dialectical fashion. In order to address such questions, we need to look at the philosophical traditions that seek to address such questions. Chapter One, “Doing the Right Thing” in Michael Sandel’s Justice, we are introduced to three positions. The first position defines justice through utility. From this perspective, justice is achieved by providing the greatest good for the greatest number of people. The second position argues that justice can only be achieved by maximizing freedom, by treating individual rights as an end in themselves rather than a means to be sacrificed for the greater good. The third position argues justice should be premised on virtue or being a ‘good citizen’. This position posits that action is ‘right’ or ‘just’ if it supports the collective understanding of the ‘good life’ and the ‘common good’. These basic positions form the framework of Sandel’s book and of our course. They will be explored in much more detail in subsequent modules but we will lay out their basic positions in this module. Finally, we look at the utility of moral dilemmas as a means for us to interrogate our own beliefs in a dialectic fashion with reason. This is the crux of what we are seeking to achieve in this course: to ask and answer hard moral questions in order to better understand what kind of society we want to live in and perhaps suggest a means of achieving such a society.

Before moving on, let us assess what kind of social agent you are.

Take the ‘Are you an Activist’ Quiz Become a factivist! (globalgoals.org)

Based on the results of the quiz, post one action below that you may take in order to be an ‘activist’?”

Use the results of this poll to guide an entry in your Journal.

- Do you agree with the assessment of the poll?

- Why or why not?

Figure 2-4: “MDGs” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 4.o Courtesy of Kjerish.

Figure 2-5: “Ally Burr from Liverpool. Patch 1 of 2” Source Permission: CC BY 2.0 Courtesy of craftivist collective.

While at the same time, the richest 1% had accrued more wealth than the other 99%. In 2017, Oxfam International reported that 8 men own the same wealth as half the world’s population, that is over 3.5 billion people. What would the welfare principle of justice have to say? Does the happiness of the 1 billion people lifted out of poverty outweigh the unhappiness generated by a vast increase in global inequality? Many people would say yes, such policies are on the whole ‘just’. But many would also acknowledge that the inequality of the system still makes them uneasy, that it seems unjust for the rich to gain disproportionately from the system.

Let us look at another example. Should justice be defined by the strongly held beliefs of the majority in a given community? Even if those beliefs infringe upon the rights of minority groups? Should maximizing the happiness of the many outweigh restrictions to be born by the few? There has been a recurring debate in many western countries, including Canada, on whether to ban Islamic dress in particular contexts, most notably the Niqab or Burqa.

Figure 2-6: “Niqab” Source Permission: CC BY 3.0 BR Courtesy of Marcello Casal Jr.

Figure 2-7: “Herat Afghanistan” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Marius Arnesen from Oslo, Norway (Behind cotton bars – Herat Afghanistan)

There is a tension in this debate between the liberal individualism in many western democratic states and the perception of practices that make some people uncomfortable. From the welfare perspective, the question is this: does the happiness generated for the majority of the population by a Niqab and Burqa ban outweigh the unhappiness generated for the minority who are affected? In 2011, France was the first European country to ban the full-face Islamic veil in public. The penalty for doing so is a 150 Euro fine. This policy was built on the earlier 2004 ban on Muslim headscarves and other ‘conspicuous’ religious symbols in schools. In 2011, Belgium banned any clothing that obscures one’s identity in public places. In 2017, Austria banned full-face veils. Other countries, including Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, and the UK, while not enacting national legislation, have banned Islamic face-covering in particular cities or in particular contexts like schools or courts.

Figure 2-8: “Stopp Minarettverbot” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of rytc.

This debate has also surfaced in Canada, specifically in Québec and under the federal Government of Stephen Harper. Let’s look at the federal example in a bit more detail. The Conservative Government of Stephen Harper banned the Niqab and Burqa during citizenship ceremonies in 2011, arguing to wear such clothing was antithetical to Canadian values.

In the House of Commons, Prime Minister Harper argued “We do not allow people to cover their faces during citizenship ceremonies. Why would Canadians, contrary to our own values, embrace a practice at that time that is not transparent, that is not open and frankly is rooted in a culture that is anti-women… That is unacceptable to Canadians, unacceptable to Canadian women.”

So, what does the welfare model of justice have to say? From this perspective, to determine if a policy is ‘just’, it is necessary to undertake utility calculus. The ‘right’ choice is the one that maximizes the balance of happiness over those who will be unhappy with the decision. What do the numbers tell us? A public opinion poll by Léger Marketing undertaken in March of 2015, asked 3,000 people a series of questions including some specifically on the Government’s ban of Niqabs and Burqas at citizenship ceremonies. It found 82% of Canadians somewhat or strongly supported the ban, with 93% support in Québec. Only 15% of respondents opposed the ban. For those who supported the ban, the wearing of the Niqab or Burqa seems to be considered an affront to Canadian values and a personal attack against them as Canadians. For the estimated 82% of Canadians who supported the ban, or just over 29 million people, the ban would arguably increase their happiness. On the other side, the banning of the Niqab and Burqa for citizenship ceremonies was estimated to affect approximately 100 women, whose happiness would suffer. From this calculation, the ban is ‘just’ according to the welfare model of justice. Even if we argue that the policy is perceived negatively by the roughly one million Muslim Canadians, the policy would still be considered ‘just’ according to welfare maximization. But for many people, the Niqab and Burqa ban felt unjust. It seemed to be rooted at best in intolerance and at worst in explicit Islamophobia. Practices that were held to be important to a minority group were being attacked simply for the comfort of the majority.

Watch the Global News video “Exclusive Ipsos poll reveals support for Bill 62 highest in Quebec”

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What is Bill 62?

- What is the intent of Bill 62?

- Why do you think there is support for Bill 62?

- Do you think Bill 62 maximizes social welfare?

- Do you think Bill 62 is ‘just’?

We also increasingly see reference to the importance of individual freedom internationally, for example in the UN Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, or the Responsibility to Protect. Although, it should be noted that the Human Rights regime has not always been able to be fully, or even partially, realized in some cases – take the atrocities occurring of the Syrian Conflict for example.

Figure 2-11: “Syria – two years of tragedy” Source Permission: Open Government Licence v1.0 Courtesy of Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

But there have also been significant achievements. Some are concrete, for example, the conviction of Ratko Mladić who was sentenced to life imprisonment by the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia for his role in the Srebrenica massacre during the Bosnian War. Some are less concrete but perhaps more important, the idea of human security versus territorial security and the increasing recognition that peace and security are indivisible from human rights.

As we will see in subsequent modules, one of the strongest positions that defines justice through individual freedom argues that individual rights are not a means but an end in and of themselves. That as reasoning beings, humans have rights that we cannot justify breaching. Think back to our example in the last section, of banning the Niqab and Burqa. From this perspective, the comfort or happiness that the majority may get from such a ban cannot justify the breach of the individual rights of the women who choose to wear the Niqab or Burqa. This tension between individual rights and collective beliefs often sits uneasily in democratic states. Yet, for many, the rights and defence of individual freedom is a prerequisite for a just society. To test this position, let us look at another hard case to put pressure on the idea that justice requires the absolute protection of the autonomy and agency of the individual.

Figure 2-13: “Explode Bomb Sustainability World Time” Source Permission: CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Courtesy of azwer.

In the ‘ticking time bomb’ scenario, it is posited that a dirty bomb has been hidden in a high-density urban area. If it detonates, estimated casualties number in the thousands, possibly tens of thousands. The leader of the group who has placed the bomb has killed all his accomplices. This means only the remaining leader knows where the bomb is. He has been captured by the authorities. They have discovered on his smartphone a countdown to detonation and there is less than 2 hours to find and detonate the bomb. It has been suggested to bring in a specialist to torture the leader. The authorities recognize that torture may not produce the required information but all other means of finding the bomb have been exhausted. Unfortunately, at this moment, you are the most senior member on the scene and all of your superiors, particularly political superiors, are conspicuously absent. You are aware that to use torture is illegal. The choice to allow the leader to be tortured or not is entirely on you. If you choose to allow the specialist to use torture, there will be no limits placed on them. In so doing, you may get the location of the dirty bomb and therefore save thousands of lives. However, you may also be held to account for your decision, especially if unsuccessful in finding the bomb, and face imprisonment yourself. If you choose not to allow the use of torture, it is almost certain that thousands of innocent people will die. If we apply the welfare model of justice, the answer would be to allow the specialist to torture the leader. The potential happiness of thousands of people dying clearly outweighs the pain or even death of one suspect. However, if we apply the strongest form of the individual freedom model of justice, the answer is no, the lives of the many do not outweigh the rights of the individual. Again, this is intentionally a hard question. What if we make it harder?

In this scenario, the leader has been strapped to a table and connected to a machine that is designed to torture a suspect as a means of interrogation. You have to choose to inflict that pain. You will be the one to torture the suspect. Does this make the choice harder? It shouldn’t according to the welfare model. But for most people, it is harder. Why? How does this influence our understanding of individual freedom and justice?

Read the BBC Ethics Primer on The Ticking Time Bomb Scenario – http://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/torture/ethics/tickingbomb_1.shtml

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What is torture?

- In the ticking time bomb scenario, is torture justified?

- Why or why not?

- Should the torturer or the person who allows the suspect to be tortured be punished?

- Does it matter if they were successful?

- Is it ‘just’ to either use torture or to have it used in the ticking time bomb scenario?

Figure 2-14: “Virtues” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of sarahtarno.

The third perspective we are going to look at is justice defined as virtue. To contextualize this perspective, think back to our discussion of torture and the ticking time bomb scenario. Even if people are uncomfortable with the idea of torturing someone in order to save many more lives, quite a few people would still side with the utilitarian approach that it would be ‘just’ to do so. But what if we make the scenario even harder. What if the only way to break the suspect, to save the many lives that will be lost if the bomb goes off, is to harm his wife or his children. Would you be willing to harm the innocent to save lives? Would you be willing to torture the innocent?

Figure 2-15: “Child’s Eye” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Tom Hickmore.

For those who identify with a utilitarian understanding of justice, the answer should still be yes, but many would be deeply conflicted. Why? The calculus has not changed. The many would still be saved by the sacrificing of the few. But we are less conflicted when we can place the blame on the person we are going to harm or allow to be harmed. This is because, at an intuitive level, many people believe that to harm the innocent is wrong. It is unjust. One way to understand this reticence is by understanding justice as virtue. From this perspective, a policy or action is ‘just’ if it affirms important societal values, or virtues. In other words, if it promotes the common good. While most modern debates on ethics fall into the welfare or freedom camps, there is often a residual element of the virtue argument present. Take the example from the chapter on price gouging after a natural disaster. The welfare perspective might argue that price gouging is ok because in the end, it encourages the provision of much-needed goods and services in a devasted area. The freedom approach to justice might agree that price gouging is ok because it allows the market to operate freely. It allows individuals to place their own value on the goods and services that they freely exchange in the market. However, while both perspectives can defend price gouging, there often remains a mental irritant to agreeing with either position. A sense that while price gouging can be defended, it is still unjust. That it is unjust to reward greed and predatory practices. That such practices and the people that employ them do not contribute to the common good.

Figure 2-16: “A damaged building and debris in San Juan, Puerto Rico” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Lorie Shaull.

Justice as virtue is determined by the actions of people as virtuous or not rather than rules to be followed. However, there is also a reason why most contemporary debates on justice often default to the welfare or freedom perspectives. These perspectives offer relatively firm guidance on what we should or should not do: maximize welfare via a utility calculation or respect individual freedom. And these are entirely defensible positions. On the other hand, the virtue perspective is more nuanced and contextual, not easily lending itself to informing specific conduct. This can result from different virtues being at odds. For example, what should one do when honesty and friendship collide or justice and mercy. There is also the problem of relativism: what is a virtue to one community may not be for another across both time and space. This becomes especially problematic when the laws of the state are used to enforce a particular virtue.

Let us take a look at a hard case for the ‘justice as virtue’ position and in particular taking into account the worry of relativism. The tension between virtue ethics and relativism can be identified when we look at the list of virtues across time and space. For example, if we compile a list of virtues in Canada of 1867 and Canada today or Canada today and Myanmar today, they would be vastly different. This is because what is considered virtuous and the ranking of virtue vary widely for each in time and place and therefore what is just, is relative. It is defined by the society in which the action is taking place, most often by the majority. As such, such virtues can also be discriminatory.

Let us consider LGBTQ rights in Canada as an example.

Figure 2-17: “Canada-Gay Flag” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 4.0 Courtesy of Osado.

While under British Colonial rule, homosexuality was illegal in the colonies and the act of sodomy was punishable by death. From Confederation to the 1960s, the laws pertaining to homosexuality were purposefully ambiguous, allowing great latitude to law enforcement. Until 1948, homosexuals could be charged with gross indecency. Between 1948 and 1961, new laws introduced labels such as criminal sexual psychopath and dangerous sexual offender. This last label, dangerous sexual offender, was applied to anyone who is likely to commit a sexual offence thereby making any non-celibate gay person a criminal. In the 1950s and 1960s, the ‘fruit machine’ was used to eliminate gay men in the civil service, the RCMP, and the military. The ‘fruit machine’ would expose subjects to pornographic images and test for pupil dilation. A watershed moment in the rights of the LGBTQ community would come with the case of Everett Klippert. In 1960, Mr Klippert, originally from Kindersley Saskatchewan but raised in Calgary was arrested and plead guilty to 18 counts of gross indecency and served four years in prison. In 1965, he was questioned by the police in regard to an act of arson at a mine in the Northwest Territories. During the interrogation, he admitted to having sex with four men and was again convicted of gross indecency and sentenced to three years in prison. Since Mr. Klippert was a repeat offender, the Crown sought to have him designated as a dangerous sexual offender. After being examined by the prison psychiatrists, he was diagnosed as an incurable homosexual and designated as such. He was sentenced to life in prison which was upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada. He wouldn’t be released until 1971. However, the injustice of Mr. Klippert’s case and the changing social mores in the late 1960s both in Canada and other countries such as the US and the UK, the rights of the LGBTQ community would begin to improve. In 1971, the first protests for gay rights took place in Ottawa and Vancouver. The Pride celebration took place in Toronto in 1972. In 1977, Québec amended its Human Rights Code to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. In 1981, in response to the Toronto Police arresting 300 men in bathhouses, 3,000 people protested in the streets. However, such raids would continue until 2002. In 1982, under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the right to non-discrimination was enshrined in the Constitution. It wouldn’t be until 1995 that the Supreme Court would rule that this right of non-discrimination would apply to sexual orientation. In 1996, this was included in the Canadian Human Rights Act. Many of the provinces would follow suit and, in 1998, the Supreme Court Ruled that Alberta’s human rights legislation must include non-discrimination of sexual orientation. This was based on the trial of Delwin Vriend, a teacher fired for being gay. However, persecution has persisted. For example, due to the scare of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, gay men could not donate blood until 2013. And even now, they can only do so if they have not had sex with a man for at least 3 months. Other victories for the LGBTQ community include lifting the ban on military service in 1992, the right for gays and lesbians to apply for refugee status in 1994, and the right of same-sex couples to adopt children in 1995. In 1999, the rights of common-law relationships were recognized for same-sex couples. In 2005, same-sex marriage was federally recognized.

Figure 2-18: “March of Hearts crowd on Parliament Hill 2004” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0

Since then, while there have been a series of advances in both the legal and social acceptance of LGBTQ rights, issues remain, particularly around social practices. So, what do we make of this from the perspective of justice as defined by virtue? If virtue and thus justice is defined by the moral position and action of the majority within a particular society, the persecution of the LGBTQ community until 1998 would be considered just. And yet most people today would rightly take issue with that position. Moreover, so would contemporary law which has enshrined non-discrimination based on sexual orientation since 1998. And before we take too much solace in the evolution of social mores in Canada, it is important to think back to the discussion on the Niqab and Burqa ban. In 2015, 82% of Canadians supported a ban on these Muslim garments at citizenship ceremonies. Further Bill C62 in Quebec attempted to impose broader bans similar to those in other European states. Aren’t these policies also discriminatory based on majority norms? Therefore, defining justice through virtue does offer some powerful insight, it can also justify injustice.

Watch the trailer for “The Fruit Machine”

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What is the Fruit Machine?

- To what purpose was it used?

- If justice is defined by virtue, can the persecution of the LGBTQ community be considered ‘just’?

- What are your thoughts on justice as defined by virtue?

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Burqa/Niqab: are both coverings worn by Muslim women. The niqab is a veil for the face that leaves the area around the eyes open. It may be worn with an eye veil. It is worn with an accompanying headscarf. The burqa is the most concealing of all Islamic veils. It is a one-piece veil that covers the face and body, often leaving just a mesh screen to see through.

Charter of Rights and Freedoms: is one part of the Canadian Constitution and was brought into force during the patriation of the Constitution in 1982. The Charter entrenches out those rights and freedoms that Canadians believe are important in a free and democratic society. Some of the rights and freedoms contained in the Charter are: freedom of expression, the right to a democratic, government, the right to live and to seek employment anywhere in Canada, legal rights of persons accused of crimes, Aboriginal peoples' rights, the right to equality, including the equality of men and women, the right to use either of Canada's official languages, the right of French and English linguistic minorities to an education in their language, the protection of Canada's multicultural heritage

Individual Freedom: refers to the position that justice is achieved by respecting the autonomy and agency of the individual

Moral dilemmas: are difficult case studies that make us question our own beliefs with both real examples and contrived thought experiments. Such Moral dilemmas force us to confront what we believe to be true, right, moral, and just. They intentionally put our convictions to the test, pushing us into dialectic reasoning between our principles and hard cases. In finding a synthesis between them, we are better able to understand and pursue justice both individually and collectively

Price gouging: refers to a situation when a seller spikes the prices of goods, services or commodities to a level much higher than is considered reasonable or fair, and is considered exploitative.

Pride events: are celebrations of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer communities. The events have also been demonstrations for legal rights such as same-sex marriage. Many pride events occur annually around June to commemorate the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City. The largest Pride celebration in Canada is held in Toronto. The first Toronto Pride celebration was held in 1981 to protest the bathhouse raids.

The ‘fruit machine’: is a device developed in Canada by Frank Robert Wake. It was supposed to identify gay men. It was called a ‘fruit’ machine since fruit was a derogatory term for gay men. The subjects were forced to view pornography. The device then measured the dilation of the subjects, perspiration, and pulse for a supposed erotic response. The "fruit machine" was used in Canada during the 1950s and 1960s in an effort to identify and force all gay men out of the civil service, the RCMP, and the military. Many people lost their jobs and the RCMP collected files on over 9,000 "suspected" gay people.

Virtue: is a trait or quality that is considered to be morally good.

Welfare: is a measurement of economic prosperity and non-economic measurements of social well being.

References

Bader, Daniel. “Virtue Ethics, Mental Illness and Discrimination”, Bipolar Village. Accessed March 30th 2018. https://www.bipolarvillage.com/virtue-ethics-mental-illness-and-discrimination/

BBC News. Jan 31 2017. “The Islamic veil across Europe“, BBC. Accessed March 17th, 2018. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-13038095

Beeby, Dan. Sep 24 2015. “Poll ordered by Harper found strong support for niqab ban at citizenship ceremonies“, CBC. Accessed March 15th, 2018. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-election-2015-niqab-poll-pco-1.3241895

Belshaw, John and Light, Tracy Penny. “Queer and Other Histories” Canadian History: Post Confederation, BC Campus. 2012 https://opentextbc.ca/postconfederation/chapter/hidden-histories/

CBC News. May 25 2015. “TIMELINE | Same-sex rights in Canada” CBC. Accessed March 17th 2018. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/timeline-same-sex-rights-in-canada-1.1147516

Levitz, Stephanie. Sept 24 2015. “Facts about one of the most controversial pieces of clothing: the niqab”, CTV News. Accessed March 5th, 2018. https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/election/facts-about-one-of-the-most-controversial-pieces-of-clothing-the-niqab-1.2579750

Macdonald, Neil. Sept 28 2005. “The niqab debate, let's not forget, is about individual rights”, CBC. Accessed March 28th, 2018. www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-election-2015-niqab-neil-macdonald-1.3246179

Paradis, Patricia and Tasneem Karbani. May 9 2017. “The Significance of the Charter in Canadian Legal History”, LawNow. Accessed March 17th 2018. https://www.lawnow.org/significance-charter-canadian-legal-history/

Ratcliff, Anna. Jan 16 2017 “Just 8 men own same wealth as half the world” Oxfam International. Accessed March 22nd, 2018. https://www.oxfam.org/en/pressroom/pressreleases/2017-01-16/just-8-men-own-same-wealth-half-world

Sorensen, Chris. Feb 16 2014. “Companies march to the beat of their own loonie tune” Maclean’s. Accessed March 21st 2018. http://www.macleans.ca/economy/companies-march-to-the-beat-of-their-own-loonie-tune/

The Global Opportunity Network. “Rising Inequality”, GON. Accessed March 22nd, 2018. www.globalopportunitynetwork.org/report-2017/rising-inequality/

The United Nations Development Program. “We Can End Poverty: Millennium Development Goals and Beyond 2015”, UN. Accessed March 12th, 2018. www.un.org/millenniumgoals/poverty.shtml

Warner, Tom. Never Going Back. University of Toronto Press, 2002.

Wyld, Adrian. March 25 2017. “Niqabs ‘rooted in a culture that is anti-women,’ Harper says”, The Globe and Mail. Accessed March 20th, 2018. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/niqabs-rooted-in-a-culture-that-is-anti-women-harper-says/article23395242/

Supplementary Resources

- Brockmann, Hilke., Delhey, Jan. Editor, and SpringerLink. Human Happiness and the Pursuit of Maximization Is More Always Better? Happiness Studies Book Series. 2013.

- Siedentop, Larry. Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2014.

- Winter, Michael. Rethinking Virtue Ethics. Library of Ethics and Applied Philosophy; v. 28. Dordrecht ; New York: Springer, 2012.