Overview

In module three, we looked at utilitarianism and its attempt to operationalize the concept of justice by maximizing welfare. As a theory of ethics, utilitarianism is consequentialist, relativist, and teleological, meaning a policy or action is good or ‘just’ based on outcomes. That each action or policy is judged in isolation, not based on a set of scriptures or overarching moral narrative. That utilitarianism has purpose, in this case maximizing utility defined by happiness. In this module, we look at a very different approach to operationalizing the concept of justice by maximizing welfare: Libertarianism. Yet, there is a natural connection between, utilitarianism, especially the variant espoused by J.S. Mill, and that of Libertarianism. In seeking to answer the critics of Bentham, and in order to save our poor Christian that we repeatedly sacrificed to the lions, Mill distinguished between higher and lower pleasures. One of those higher pleasures was the defence of individual rights which Mill argued held a privileged place in society. He noted that this privileged place was evident from the degree of sanctions imposed on those who breach basic rights. He also posits, as we saw in Module 3, that the defence of basic rights is both a necessary element of justice and a necessary means to secure the general happiness. But, as Sandel notes, does Mill’s emphasis on basic rights operate independently of utility? If so, then the internal logic of utilitarianism is suspect, and this suggests we should examine other conceptualizations of justice. Like utilitarianism, Libertarianism also looks to individual rights as a defining feature of justice. It is argued such rights are the fundamental unit of morality and ethics and actively opposes any infringement of individual rights. Most specifically, Libertarians oppose limitations imposed by the state and rail against its paternalism, especially the imposition of morality legislation and wealth redistribution. For Libertarians, justice is not based on outcomes like utilitarianism, justice is defined through a defence of individual liberty. Libertarians recognize the inherent right of humans to exercise free will to guide their lives and on the right of individuals to own the successes and failures that are derived from this. Libertarians look to minimizing the role of government, maximizing personal freedom, and promoting personal responsibility. In this module we will look at Libertarianism and its conception of justice.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the basic principles of Libertarianism

- Debate the concept of self-ownership

- Apply the principles of Libertarianism and self-ownership to the idea of justice

- Read Chapter 3 in Michael Sandel’s Justice

- Take the “World’s Smallest Political Quiz”: https://www.theadvocates.org/quiz/

- Post your Quiz Results on the Live Poll App

- Complete Learning Activity #1

- Read: https://www.theadvocates.org/2014/12/eyeball-lottery-powerful-argument-self-ownership/

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Watch the Broadbent Institute’s video “Wealth Inequality” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zBkBiv5ZD7s&feature=youtu.be

- Watch the TheRulesOrg’s video Global Wealth Inequality: https://youtu.be/uWSxzjyMNpU

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Altruism

- Civil liberties

- Collectivism

- Free-markets

- Free-riding

- Free will

- Inherent rights:

- Limited government

- Morality legislation

- Natural harmony of interests

- Non-aggression principle

- Objectivism

- Paternalism

- Public good

- Respect for personal property:

- Self-ownership

- Social contract theory

- Spontaneous order

- Wealth redistribution

Michael Sandel, Justice, “Libertarianism” pg. 58-74 [Textbook]

“The Eyeball Lottery” https://www.theadvocates.org/2014/12/eyeball-lottery-powerful-argument-self-ownership/ [Online]

Learning Material

Figure 4-3: “John Stuart Mill” Source Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 4-4: “Adam Smith” Source Permission: Public Domain.

Figure 4-5: “Thomas Jefferson” Source Permission: Public Domain.

By collectivism, Libertarians are referring to the move towards government control and regulation of the national economy and civil society, with the strongest form of collectivism argued to include communal ownership of resources. In response, economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman argued that government intervention in the economy to address inequality would necessarily be coercive, counter-productive, and ultimately illegitimate.

Figure 4-7: “Friedrich Hayek” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 3.0

It is coercive since any governmental interference in economic and social systems is backed up by the threat of force – if you do not comply, the state may compel you or punish you. It is counter-productive since any government intervention is at best inefficient and at worst results in the opposite outcome desired. For example, a Libertarian might argue that contrary to its intent, minimum wage laws will result in more job insecurity and vulnerable people being less well off. Ultimately, Libertarians argue such intervention is illegitimate since it requires the government to infringe upon individual rights even when the exercise of such rights does no harm to anybody else. For example, forcing someone to save for their retirement via the Canadian Pension Plan violates their individual right to exercise free will, to determine when and how to spend what they have earned. Perhaps the two most important influences on contemporary Libertarianism are Ayn Rand and Robert Nozick.

Figure 4-10: “Robert Nozick” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Harvard Gazette.

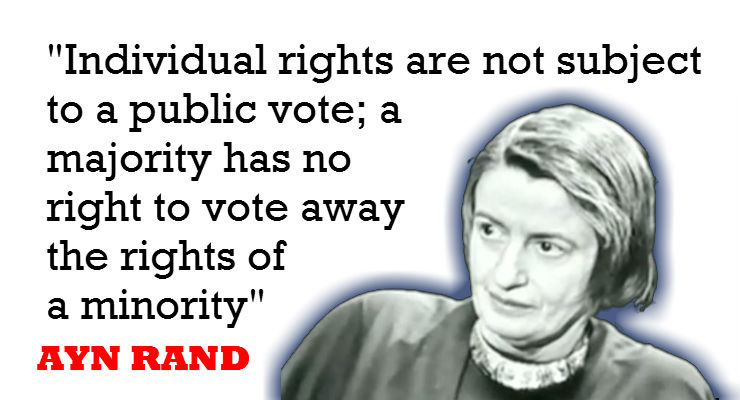

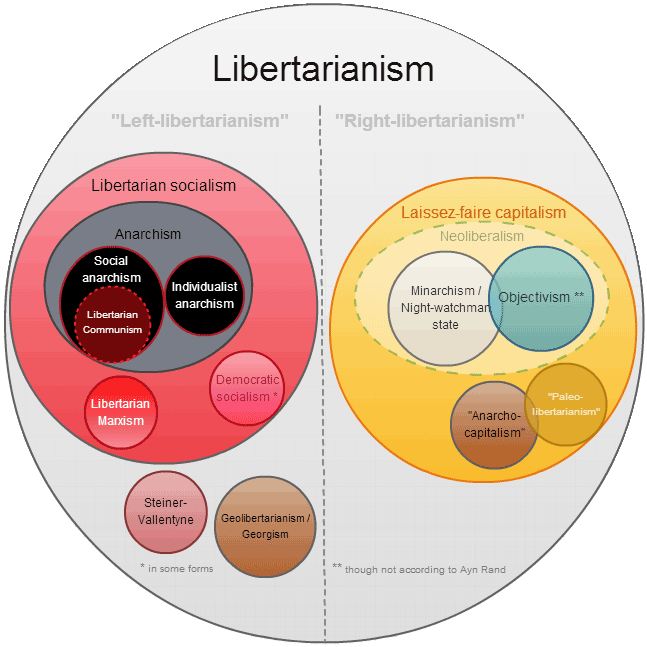

While Rand specifically disavowed the Libertarian movement of her time, the themes of her writing have been very influential for Libertarians. Specifically, in Atlas Shrugged, Rand problematizes the connection between altruism and political collectivism, which she argues inevitably leads to tyranny. Instead, she posits ‘objectivism’ as more practical and ethical. Objectivism argues individuals should regard their own happiness as the metric of what is right and good and that individual reason is the only guide to morality. In this, we see strong support for individualism, free exchange through capitalism, and limited government to support both. Nozick argues that individual rights are so fundamental that the question becomes not what the state should do but rather what, if anything, the state can legitimately do. He concludes that the only legitimate role of the state is enforcing contracts, protecting people from the use of force, and guarding people against fraud and theft. From these ideas, modern Libertarianism took its current form. Theoretically, Libertarianism is fairly simple and consistent – maximize individual freedom. In practice, there are inconsistencies between those on the right and those on the left. Those on the right may support a very limited state and be in favour of free markets, but they often are less consistent on the issue of civil liberties: abortion, pornography, prostitution, and sexual orientation. Those on the left also question the legitimacy of the state but they are more consistent on the issue of civil liberties. However, they also question other forms of power, specifically in the free-market where corporations and management exercise considerable coercive power.

Figure 4-11: “Libertarianism” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Finx.

In this module, we are going to first look at the basic principles of Libertarianism, followed by an examination of the core concept of ‘self-ownership’, and conclude with a look at the connection between Libertarianism and justice.

Before moving on, test your Libertarian inclinations:

Take the “Political Quiz”: political quiz (polquiz.com)

On the live poll app select:

[yop_poll id=”14″]

When introducing Libertarianism, the discussion can get quite complicated. As mentioned earlier, in practice there are inconsistencies between left-wing and right-wing Libertarians. But for its proponents, there is a core set of principles that they mostly agree on. In this section, we are going to first introduce this broad set of principles and conclude with the two core principles: the ‘non-aggression principle’ and ‘respect for personal property’.

The broader set of Libertarian principles begin with individualism and individual rights. Libertarians posit the individual as the basic unit of social analysis. Individuals are conscious agents. They are able to make rational decisions. And they are responsible for the outcomes of those decisions. Therefore, the source of morality and ethics within society is based on the recognition and application of the importance of individualism. The key to this argument is the primacy of individual rights. Morality and ethics in society are based on the protection of these rights, specifically the right to be secure in one’s life, liberty, and property. These are inherent rights since they are derived from simply being human and are not conferred by some other authority. If these are inherent rights, any breach is highly suspect – whether it is by a criminal or the state itself.

At the heart of this position is the Libertarian’s deep skepticism of power, especially state or government power. While many non-Libertarians see the state as a protector of rights, Libertarians see this as a naïve and dangerous proposition. They argue the state is erroneously held to different standards than individuals and is given more coercive instruments of authority that extend into areas that infringe on individual rights and liberty. Libertarians argue only a very minimal state is necessary to protect people’s life, liberty, and property. They disagree with the proposition that to be safe, we need regulatory bodies and government officials to ensure labour, environmental, or health standards are being met; that we need progressive taxation to ensure a more equitable distribution of resources; that we need the state to achieve a degree of equity in society. Libertarians are deeply skeptical of all of this. They see the state as being constituted by people and believe that it has no greater moral or ethical authority than individuals do. They, therefore, argue for a very limited form of government that should have no greater coercive authority than is necessary to ensure individual liberty. Yes, the ‘rule of law’ is necessary but not to impose particular visions of the ‘good life’. Instead, the rule of law should be applied in order to protect people from the use of force, to ensure contracts are enforced, and that people are protected from fraud and theft.

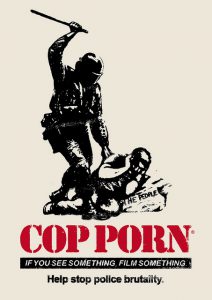

Figure 4-13: “Police Brutality” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Christopher Dombres.

As a corollary to this, Libertarians argue that the state is often unnecessary to provide those things people are looking to the government to provide. They acknowledge that society is constituted by complex ordering mechanisms but believe that for the most part, such mechanisms do not require a strong centralized authority. Rather, Libertarians point to the development of language, laws, markets, and civil society as having developed without, or even in opposition to, strong centralized authority. This is because Libertarians believe that there is a spontaneous order to society that coalesces out of the daily actions of individuals who interact with others to achieve their goals. Foremost of these goals are security and prosperity which form a natural harmony of interests for all people. Everybody wants the right to live their lives as they see fit. To work as much or as little as is necessary to achieve this. Libertarians believe that there is no valid ethical or moral argument to interfere in this spontaneous order and natural harmony of interests.

That is not to say everybody will agree with everybody and everything all the time. Libertarians recognize that people’s interests will conflict. But they do argue that there is a better way to resolve such conflict than a default position of referring all conflict to the state: the free-market. Free markets are an example of a spontaneous order, whereby people freely exchange goods and labour to foster peace and prosperity. This exercise is based on the ideas of private property and exchange, which Libertarians posit as the basis of a free society. You have the right to sell or trade what is yours, including your labour, for whatever you and the other party find acceptable. Further, this exchange is not limited to the pursuit of wealth but is argued to be a more efficient mechanism to alleviate poverty and foster cultural richness in society than state-directed activity. If people value the fine arts or other cultural activities, they will fund them. If they are not funded, they will perish by the logic of the free market. If people wish to address questions of poverty, they will donate money to charities of their choice.

Figure 4-16: “Thailand. Ratchaburi. The floating market.” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Vladimir Tkalčić.

Figure 4-17: “The Grand Bazzar in Istanbul” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Taehyun Kim.

Libertarians view the intervention of the state in such spontaneous orders as both inefficient in outcomes and costly in practice. It is inefficient because the red tape, the bureaucracy, and the Machiavellian nature of party politics make policy and action slow, expensive, and often unfit for the purpose it was devised for. Think about the Canadian Pension Plan (CPP). It was created in 1965 as a means to provide regular income to contributors upon retirement at age 65. The CPP was motivated by the increasing trend of poverty noticed among retired Canadians. It is a compulsory contributory plan, meaning individuals must pay into the program based on their income. This also means that it is your money that you eventually get back. However, we regularly hear the CPP is underfunded and that the government can’t afford such programs. On the other side, we hear of high public pensions creating the very problem of underfunding. For years, the CPP has been a hot potato thrown back and forth between Liberal and Conservative governments, each reluctant to take measures to address chronic underfunding. The Libertarian Party of Canada concludes that the CPP is a “fraudulent, virtually bankrupt, and increasingly inadequate and oppressive” regime.

Figure 4-18: Source Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

Ultimately, if Libertarian principles are applied to their logical extension, its advocates believe a more just, ethical, prosperous and peaceful world can be created. Two core principles are often cited as the means to do so in practice: the non-aggression principle (NAP) and ‘respect for personal property’.

The NAP and ‘respect for personal property’ form the foundation of Libertarianism in practice. Libertarians argue they are so fundamental that they are two of the first things almost everybody teaches their children: don’t hit and don’t steal.

Figure 4-19: “kindergarten-4341” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Howard County Library System.

Further, it is argued that if these principles are taken to their logical conclusion, we would arrive at a peaceful and prosperous world constituted by individual liberty. The NAP means you are not morally allowed to initiate the use of force against a person or their property. You may of course defend yourself from others using force against you, but you cannot morally initiate the use of force. If we think about the NAP in our personal lives, it makes sense. We should not use force to deprive people of their property nor to damage it. This sounds simple but it is really quite far-reaching if taken to its logical conclusion. Think about the state. Libertarians see the government as merely constituted by individuals. As such, the people who represent the government have no greater right to initiate the use of force than any other person. When the government passes and enforces legislation that does anything more than protect an individual’s liberty, they are initiating the use of force since noncompliance is punishable by the police and the courts. When the government punishes someone for not wearing a helmet while riding a motorcycle or using illegal drugs, they are initiating the use of force. Such behaviour may pose a threat to the person riding the motorcycle or using the drugs, but they are not harming others. These lawbreakers have not initiated the use of force. But when the state intervenes to compel individuals to act in particular ways, force has been initiated. For Libertarians, if that use of force cannot be justified by defending individual liberty, it is illegitimate and immoral.

Figure 4-21: “Police Stop” Source Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Thomas Hawk.

For Libertarians, the NAP extends to a person’s rightfully owned possessions as well. And this bridges us to the second point – respect for personal property. Libertarians argue that individuals have a right to keep that which their labour has created, whether that be goods or some form of remuneration. Individuals have the right to keep, trade, or sell that which they have created or earned as long as it does not infringe on the freedom of others to do likewise. For Libertarians, any attempt to deprive someone of their personal property, or to use it against/without their consent, is an act of aggression. This respect for property rights is crucial for Libertarians for a couple of reasons. First, Libertarians argue people are in possession of inherent rights, including life, liberty, and personal property. Thus, defending these rights is important to the pursuit of achieving the ‘good life’. Second, Libertarians believe both in extremely limited government and spontaneous social ordering mechanisms. Foremost of these mechanisms is the free-market which allows individuals to buy, sell, and trade their personal property. Such exchange allows individuals to have the quality of life they desire within the constraints of their abilities and means. The free-market thus requires individuals to have the right to control their personal property. Again, all of this sounds quite reasonable. But what about when we take it to its logical conclusion from a Libertarian point of view? What about when we look at the degree to which the state respects personal property? From a Libertarian perspective, the government does not respect people’s personal property very well, particularly with the institutionalization of the welfare state. In order to support the welfare state, governments can impose greater taxation or run a deficit.

Figure 4-22: “Loot and Extortion” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of Chris Hoare.

Figure 4-23: “Taxation is theft” Source Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Jukie Bot

Libertarians argue this is unilaterally depriving individuals of their rightfully owned property either now or in the future. Further, they argue this is the initiation of force – the taking of one’s property, in this case, citizen’s money, without their consent and with the threat of being arrested and jailed for non-compliance. Such redistributive policies and taxation are in violation of the NAP and are therefore ‘unjust’.

In your Journal, consider the following example and reflect on the given questions:

Libertarianism is premised upon individualism and individual liberty. Many people would suggest that climate change, however, is fundamentally a collective problem: the cause of climate change is complex and involves the actions of many individuals and institutions, and the harms that arise (and will continue to arise) from climate change (e.g. destruction of farmland, flooding, natural disasters, fires) affect many people and institutions. Furthermore, those most affected by climate change often will be those who contributed least to this problem. Lastly, it seems that collective action will be required to mitigate climate change.

- Does the libertarian non-aggression principle hold in the context of climate change? For example, Bob is a high carbon dioxide (CO2) emitter. If Bob knows that emitting carbon contributes to climate change and that climate change can hurt other individuals (who have never hurt, let alone encountered, Bob), is Bob violating the non-aggression principle?

- More broadly, from a libertarian perspective, should individuals be responsible for the ways in which they contribute to climate change? If so, how? If not, why not?

- From a libertarian viewpoint, would Barney, who has been harmed by climate change (he lost his farm and thus his livelihood to flooding that was the result of increased sea levels), be justified in responding with violence to those who contribute most to climate change (for instance, would Barney be justified in harming Bob, who is a high carbon dioxide (CO2) emitter)?

Figure 4-24: Permission: Courtesy of course author Martin Gaal, PhD Lecturer, Department of Political Studies, University of Saskatchewan.

At a deeper level, both the NAP and respect for personal property rest on the concept of self-ownership: that each person is the moral and rightful owner of themselves, that no one can make ownership claims on anyone else, and no one owes anyone else anything. Self-ownership is connected to the NAP since it is a form of individual sovereignty defined as no higher legitimate authority above the individual.

Therefore, no one has the right to deny your individual liberty unless, in its exercise, you would be denying others the same right. Personal property becomes an extension of self-ownership if it has been legitimately acquired through initial acquisition or free exchange.

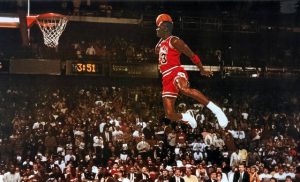

This is important for the functioning of the free-market which is the Libertarian’s primary means of creating a prosperous and peaceful society. The free-market is built on the ideal of people freely exchanging that which they have ownership of – their goods and their labour. But perhaps most importantly for Libertarians, self-ownership is primarily a moral principle since anything less than full self-ownership would be an endorsement of at least a minimal version of slavery. In the text, Sandel builds a contemporary example from Nozick’s argument by asking who ‘owns’ Michael Jordan.

The point of the story is that if the government can compel Michael Jordan to give a percentage of his salary to the government, it is claiming a part of his labour. If the government can claim part of his labour, it is in essence forcing Jordan to give the government part of his time. That means the government is asserting a property right over Jordan. If the government can assert a property right over Jordan, he is not fully free – which by definition means he has been at least partially enslaved. At a certain level, this argument seems frivolous. Nobody in their right mind is going to say Michael Jordan, Beyoncé, or Bill Gates are slaves of the state. But it does make us think about the degree to which we do ‘own’ ourselves and the degree to which others, most notably the state, make claims upon us. The concept of self-ownership stakes a strong claim of individualism and this is a position that resonates with many hotly debated topics today: reproductive rights, privacy rights, sexual rights, end of life rights, et cetera. When does the government have a right to interfere in decisions that affect my body? That affect my conscience? That affect my lifestyle? And who or what has the right to make such distinctions?

While many of these questions may seem more or less settled in Canada, take a closer look at the world around us. Only 60 countries out of 193 provide safe and legal access to abortions. Just south of the border, in Iowa, a current bill has been proposed to make abortions illegal when a fetal heartbeat is detected which can be as early as 6 weeks. Or how about slavery? In 2017, CNN reported on the active slave markets in contemporary Libya, where you can buy a slave for as little as $400 US. This is not human smuggling, where organized criminal syndicates evade law enforcement to undertake illicit activities. These are actual markets that are selling human beings.

Figure 4-29: “Tanzanian Anti-Slavery Monument” Source Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Jon Wiley.

We could also look at the 50 countries which actively suppress religious freedom. Or examples of ethnic cleansing, like that happening in Myanmar.

Figure 4-30: “Burnt down house in northern Rakhine State” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Moe Zaw.

Or the extreme restrictions placed on citizens in North Korea. And before we get too comfortable here in Canada, what are the implications of the Indian Act for the idea of self-ownership. The Indian Act is deeply paternalistic and has severely restricted the rights of Indigenous peoples. For example, Status Indians were one of the last groups in Canada to gain the right to vote in 1960.

Figure 4-31: “Hiawatha Council Hall” Source Courtesy of Nick Nickels/Library and Archives Canada/PA-123915 © Government of Canada.

From this perspective, Libertarianism can seem quite compelling, especially the NAP and principle of self-ownership. However, as we will discuss in the next section, there are implications of this position when thinking about questions of justice.

Read “The Eyeball Lottery” https://www.theadvocates.org/2014/12/eyeball-lottery-powerful-argument-self-ownership/

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What is the eyeball lottery?

- How does the eyeball lottery support the argument of self-ownership?

- What if the donation of an eyeball was voluntary?

- Should it be allowed?

- What if someone wanted to voluntarily donate their heart of their own free will?

- Should that be allowed?

- Would it matter what motivation someone had to make such a donation?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the self-ownership concept?

Having introduced and discussed the foundational principles of Libertarianism, let us now turn to the question of justice. At the most basic level, Libertarians equate justice to liberty as defined by the space created for individuals to exercise free will. Remember the foundational logic of a Libertarian philosophy is premised on individuals as the basic unit of social analysis. Individuals are rational agents and when able to exercise free will, they make decisions best suited to their needs and wants. Moreover, as rational agents making free choices, they own the outcomes of those decisions. If they achieve personal success and prosperity, they own that. If they suffer from the consequences of bad choices, they also own that. Both examples are ‘just’ if they are the result of individuals exercising free will, the only caveat being your exercise of free will cannot impede on the ability of others to do the same. Libertarians do not recognize any higher authority than the individual. The state or other governing institutions have no moral right to impinge on an individual’s inherent rights of life, liberty, and property, even if the purpose of doing so is to address issues of inequality or poverty. To do so would be coercive and ‘unjust’. Instead, they argue that governing institutions are both created by and constituted by individuals and that the purpose of those governing institutions is to protect inherent rights. It is therefore argued that individualism and the protection of individual rights are the basis of morality and justice. This stands in stark contrast to the consequentialist perspective we saw in utilitarianism. For Libertarians, questions of justice do not ask about outcomes, but rather they ask questions about process: have people and their rightfully owned property been treated justly? If so, the outcomes are ‘just’ regardless of any negative social conditions such as poverty or inequality. This tension between outcomes and process will be dealt with a bit later in this section.

Figure 4-32: “Freedom, Liberty, Equality and Justice” Source Permission: CC BY-NC 2.0 Courtesy of Mark K.

If we dig a bit deeper, there are some more nuanced and problematic aspects of Libertarianism and questions of justice. In order to examine these tensions, we will look at some of the core concepts of Libertarianism. Let us begin with one of the core pillars of Libertarianism in practice, the non-aggression principle. As a reminder, the NAP simply states that an individual is not morally permitted to initiate the use of force. To do so is ‘unjust’. And this seems like one of those simple golden rules that we teach our kids – don’t hit. But at the larger societal level, this becomes more complicated, especially the absolutist nature of the claim. What if by initiating a minimal degree of force, larger harm is avoided? For example, what if through a minimal level of taxation imposed on the richest among us, we were able to end world hunger? Or vaccinate the world’s poorest children? Or provide universal primary education? This is certainly the initiation of the use of force, but would it be unjust? Does the absolutism of the NAP make it unworkable?

Figure 4-33: “Malnourished Somali Child in Hospital” Source Permission: This material has been reproduced in accordance with the University of Saskatchewan interpretation of Sec.30.04 of the Copyright Act.

Figure 4-34: “Semana de Vacunación en las Americas 2014 – Paraguay” Source Permission: CC BY-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Pan American Health Organization PAHO.

Figure 4-35: “Girls’ Education Forum 2016” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of DFID – UK Department for International Development.

Another criticism of the NAP is that it allows harm to come to those you have a duty over. Consider children and car seats, would it be ‘just’ to allow a child to sit unrestrained while driving on the highway? Would it be ‘unjust’ to initiate the use of force against a child if they refused to do so? What about allowing a child to starve to death? If you do not forcibly prevent them from eating, would allowing this to happen, be considered ‘just’?

The concept of self-ownership and its implications for justice also raises some interesting questions. Remember self-ownership means that each person is the moral and rightful owner of themselves, that no one can make ownership claims on anyone else, and no one owes anyone else anything. The most obvious objection to self-ownership as applied to justice is this last point: no one owes anyone else anything. If we encounter a child drowning and we are capable of saving them, would it be ‘just’ to refuse to do so? The strongest position of self-ownership is that a person may choose to help the child and many likely would. But it is not ‘unjust’ if they choose not to.

Figure 4-36: “its awful” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of XXOOPP.

From a Libertarian perspective, justice resides in the freedom of choice because of self-ownership and one’s inherent rights.

A second objection arises with the very concept of ownership. If you ‘own’ yourself, it is implied you can do all the things associated with ownership. For example, you should be able to freely transfer ownership of yourself to another if no coercion is involved. In other words, can you sell or give yourself to another? And would it be just to do so? Take for example the voluntary cannibal in the textbook. Under the principle of self-ownership, would it be just to give yourself to another to be killed and eaten?

A final objection to a rigorous defence of self-ownership is the possibility of inefficient or detrimental outcomes. This is likely when it comes to public good problems and especially in large societies where free-riding is more likely. In some cases, a minimal infringement of personal rights can produce a greater societal good. For example, what if the government imposes a minimal level of taxation for universal health care in order to achieve significant gains in everybody’s quality of life? This would violate the principle of self-ownership since it is imposed, but would such a violation be ‘unjust’?

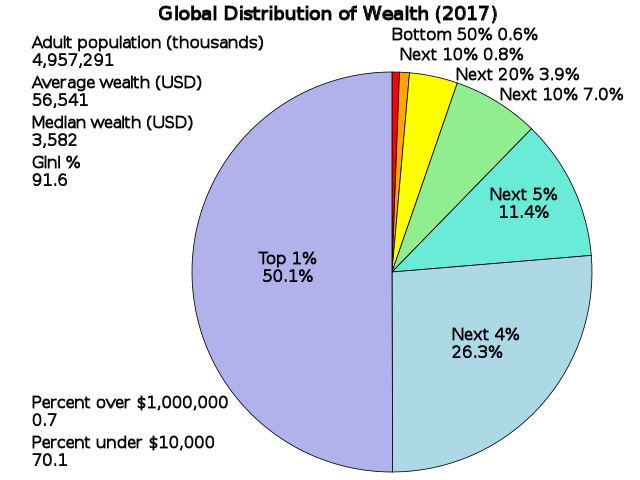

Figure 4-37: “Baby” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of eloisa.

However, when considering questions of justice, Libertarians are most vulnerable on the issues of poverty and inequality. For Libertarians, justice is determined by process: have individuals and their property been treated fairly? Have they been allowed to exercise their free will? Have their inherent rights to life, liberty, and property been protected? If they have, the outcome is just, regardless of what that outcome may look like. This is premised on Nozick’s argument of distributive justice. He argues that if your initial holdings were gained legitimately and your subsequent gains were made via free exchange in the marketplace, the outcomes are just. You are entitled to your personal property and wealth. No one, not even the state, has the right to take what you legitimately own. This means that Libertarians believe a state of inequality is just. They may argue that individuals who do not like a state of inequality can individually volunteer their property and wealth to reduce inequality, but this is a question of preference not justice. What about inequality in Canada and the world today? Globally, 8 men have the same cumulative wealth as the poorest half of the world’s population or approximately 3.5 billion people. In Canada, the top 20% of Canadians control 70% of the countries wealth. The top 10% control 60% of all financial assets which is more than the poorest 90% combined. The richest 86 families in Canada have the same cumulative wealth as the poorest 11 million Canadians. Since 1999, the net worth of the top 20% of Canadians has risen by 80% while the net worth of the bottom 20% has only risen by 38%. If the wealthiest of Canadians legitimately acquired their initial holdings and if those holdings increased through free exchange on the open market, Libertarians would deem both current inequality and the pattern of increasing inequality as just. It is the process that matters, not outcomes.

Watch the Broadbent Institute’s video “Wealth Inequality”

Watch the TheRulesOrg’s video Global Wealth Inequality:

*note: The claim that 300 people have nearly have the world’s wealth has been updated to 8 men in 2018. This video is being used since it correlates with the dates used in the Canada video

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What is the difference between how Canadians believe wealth is/should be distributed and how it is actually distributed?

- How would a Libertarian respond to the first video?

- What do you think about the video and a Libertarian response to it?

- How is wealth distributed globally?

- How would a Libertarian respond to the second video?

- What do you think about the video and a Libertarian response to it?

- In speaking to justice, does it matter if we are looking at Canada or the World?

- To a Libertarian?

- To you?

- Based on this module, do you agree or disagree with the Libertarian understanding of justice? Why?

This module has sought to introduce and problematize the concept of Libertarianism and apply it to the idea of justice. On its face, Libertarianism starts with a very simple proposition: individual liberty is the most important political value and is, therefore, a fundamental element of justice. It gained traction as a response to the increased role that government has played in society with the rise of the welfare state. Libertarians believe such big government is both coercive and illegitimate. The Libertarian argument starts by posting the individual as the basic unit of social analysis: people are conscious rational decision makers who are best able to make decisions for themselves. Moreover, they are responsible for the outcomes of their decisions, whether those outcomes be positive or negative. They argue that individuals have inherent rights to life, liberty, and property. The only legitimate role of the state is to protect those rights, meaning the only legitimate form of government is limited government. This argument is partially based on the idea that institutions like the state are constituted by individuals and therefore should have no more rights or authority than that of individuals. Instead, Libertarianism looks to people’s natural harmony of interests and spontaneous order to fill most of those functions people look to the government to provide. The most important example of a spontaneous order is the free market whereby individuals can freely exchange their labour and property. Within this order, individuals can achieve the degree of success and prosperity that they are able to, as measured by their capabilities and effort. In practice, Libertarianism promotes the non-aggression principle, respect for personal property, and self-ownership. If taken to their logical conclusion, Libertarians argue the application of these principles will create a peaceful and prosperous world based on individual liberty. As applied to justice, Libertarians do not look to outcomes. Rather they look to process: are individuals given the space to make choices based on free will? Are individuals able to freely exchange their labour and property in the marketplace? If these conditions hold true, it is justice. Again, this all seems very straightforward: don’t hit and don’t steal. Allow people to make choices without coercion. But, as we saw, there are questions that challenge this proposition. If people truly own themselves, should they be able to freely give away their lives? Is it just to do so to benefit their family? What about the example of consensual cannibalism, is that just? Is it just to allow the maintenance of inequality both at home and abroad? In contrast to the precepts of self-ownership and in order for ‘justice’ to prevail, do we not have duties towards others? Conversely, is it not more just to minimally encroach on such individual rights to achieve societal goods such as education, healthcare, or poverty reduction. Libertarianism does make some strong and compelling arguments as to empowering free will and limiting the ability of coercive force on an individual’s exercise of free will. However, taken to its logical conclusion, many people may conclude that Libertarianism’s take on what is ‘just’ is still problematic. In the next module, we will look at the role of the market as a means to achieve justice.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Altruism: “Behaviour… motivated by a desire to benefit someone other than oneself for that person’s sake” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [hereafter SEP]). Claims that morality “consists in living for others or for society,” an idea rejected by objectivism (Rand 1957, 1075).

Civil liberties: are personal rights and freedoms that are protected from interference by others, most specifically governmental authorities

Collectivism: is an approach to policy and action which privileges centralised authority. The strongest thesis of collectivism borders on socialism. It is often used to juxtapose policy or action from individualism in methodology, social philosophy, ethics, and the explanation of social phenomena.

Free-market: an economic system which operates largely free from governmental interference. As a system it privileges the setting of prices through the forces of supply and demand. For Libertarians, it is considered an important means to mitigate conflict and allow individuals to achieve prosperity thourgh free exchange.

Free-riding: a problem with voluntary collective action that results because an individual can enjoy the benefits of a group action without contributing towards it.

Free will: a philosophical conception touched on by most thinkers of the past two millennia. Refers to the capacity of rational agents to choose a course of action from alternatives.

Inherent rights: Morality and ethics in society are based on the protection of these rights, specifically the right to be secure in one’s life, liberty, and property. These are inherent, since they are a derived from simply being human and are not conferred by some other authority.

Limited government: a government which is constrained through a written constitution by explicitly limiting the powers that the people delegate to government. The stronger thesis of this idea argues the default position should be that if the government has not explicitly been given a prerogative, it should be prevented from exercising it.

Morality legislation: laws drafted and executed by the government which impose limitations on people’s personal liberty based on morality positions. These may include laws on reproductive rights, sexual orientation, or behaviour such as drinking alcohol, smoking, or using prohibited drugs.

Natural harmony of interests: a Libertarian view that there is a natural harmony of interests among peaceful, productive people in a just society. It stands in opposition to government policy which interferes in this order, benefiting some over others and thereby creating the impetus for political conflict.

Non-aggression principle: is an important Libertarian principle which forbids all forcible interference with any individual’s person or property except in response to the initiation.

Objectivism: is an important part of Ayn Rand’s “philosophy for living on earth.” It is an integrated system of thought which asserts reality is independent of us and that the proper moral purpose of one's life is rational self-interest or the pursuit of one's own happiness. As a corollary, this implies laissez-faire capitalism is the only social system morally consistent with such a position.

Paternalism: is a policy or practice whereby one actor makes decisions on behalf of other subordinate actors and in so doing restrict their freedom and responsibilities.

Public good: in economics, a good which is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. In other words, something where its use by one does not reduce its utility to others and where it is difficult to prevent others from its use.

Respect for personal property: Libertarians argue that individuals have a right to keep that which their labour has created, whether that be goods or some form of remuneration. Individuals have the right to keep, trade, or sell that which they have created or earned as long as it does not infringe on the freedom of others to do likewise

Self-ownership: the idea that individuals possess full control rights over the use of an identity, both as a “liberty-right to use it”, and as a “claim-right that others not use it”

Social contract theory: for Libertarians this builds on the view of the Greek philosopher Epicurus. He argued justice is social contract between the members of a society not to do harm to each other and is a requirement to enjoy the benefits of living together in society.

Spontaneous order: while it is easy to assume that order “must be imposed by a central authority,” Libertarian analysis views the most fundamental institutions in human society – language, law, money, and markets – as developing spontaneously (Cato Institute).

Wealth redistribution: are state policies intended to transfer income from some members of society to others. This is most often accomplished through taxation but can also be achieved through things like land reform, monetary policy, or confiscation.

References

Boaz, David. 1999. “Key Concepts of Libertarianism.” Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/key-concepts-Libertarianism

“Canada’s Pension Plan Changes: 5 Things To Know.” Huffington Post. December 2017. https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2017/12/14/canada-pension-plan-changes-5-things-to-know_a_23307265/

Cousins, Sophie. 2018. “The Rohingya Have Fled One Crisis for Another.” Foreign Policy. http://foreignpolicy.com/2018/05/15/the-rohingya-have-fled-one-crisis-for-another/

Coates, Ken. 2008. “The Indian Act and the Future of Aboriginal Governance in Canada.” National Centre for First Nations Governance. http://www.fngovernance.org/ncfng_research/coates.pdf

Cross, Philip. 2016. “The Ugly Truth Behind the Plan to Expand the Canada Pension Plan.” Macdonald-Laurier Institute for Public Policy. https://www.macdonaldlaurier.ca/cpp-expansion-skimming-our-savings-for-unfunded-public-pensions-philip-cross-in-the-financial-post/

Dangerfield, Katie. 2017. “Rohingya crisis explained: Why the minority Muslim group is fleeing Myanmar.” Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/3740246/rohingya-crisis-in-myanmar/

Delahanty, Julie. 2015. “Part of the inequality problem.” Oxfam Canada. https://www.oxfam.ca/news/part-inequality-problem

Elbagir, Nima, Raja Razek, Alex Platt, Bryony Jones. 2018. “People for sale: Where lives are auctioned for $400.” CNN Exclusive Report.https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/14/africa/libya-migrant-auctions/index.html

Erickson, Amanda. 2018. “The many countries where abortion is basically banned.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2018/05/24/the-many-many-countries-where-abortion-is-basically banned/?noredirect=on&utm_term =.ba79468db301

Hardy, Catherine. 2018. “Which state has passed the most restrictive abortion ban in the US? Euronews. http://www.euronews.com/2018/05/02/which-state-has-passed-the-most-restrictive-abortion-ban-in-the-us-

“Global Restrictions on Religion Rise Modestly in 2015, Reversing Downward Trend.” Pew Research Centre. April 2017. http://www.pewforum.org/2017/04/11/global-restrictions-on-religion-rise-modestly-in-2015-reversing-downward-trend/

“Libertarianism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Revised July 2014. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/Libertarianism/

McMahon, Tamsin, Ken MacQueen. 2014. “Canada’s looming pension wars.” Maclean’s. https://www.macleans.ca/politics/canadas-looming-pension-wars/

Merryweather, Aunt. 2014. “What is Left-Libertarianism?” Thoughts on Liberty. http://thoughtsonliberty.com/what-is-left-Libertarianism

Mintz, Eric, David Close, Osvaldo Croci. 2012. Politics, Power and the Common Good. Toronto: Pearson.

Rand, Ayn. 1957. Atlas Shrugged. New York: New American Library.

Rothbard, Murray N. 2010. “The Left and Right within Libertarianism.” In WIN: Peace and Freedom through Nonviolent Action. https://mises.org/library/left-and-right-within- Libertarianism

Russell, Dean. 1955. “Who Is a Libertarian?” Foundation for Economic Education. https://fee.org/articles/who-is-a-Libertarian/

“Statement of Policy.” Libertarian Party of Canada. Last Amended July 2016. https://www.Libertarian.ca/statement_of_policy

Sturgeon, Jamie. “Wealth gap widens in Canada as richest see faster rise in net worth.” Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/2033927/wealth-gap-widens-in-canada-as-richest- see-faster-rise-in-net-worth/

Youtube. 2014. “Wealth Inequality in Canada.” Broadbent Institute. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zBkBiv5ZD7s&feature=youtu.be

Supplementary Resources

- Machan, Tibor R. 2006. Libertarianism Defended. Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

- Nozick, Robert. 1974. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. New York: Basic Books.

- Palmer, David, and Oxford Scholarship Online. 2015. Libertarian Free Will Contemporary Debates.

- 2009. “Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 03: ‘Free to Choose” Harvard university, 55:09, a lecture by Michael Sandel published on 9 Sept 2009. Accessed May 24th https://youtu.be/Qw4l1w0rkjs