Overview

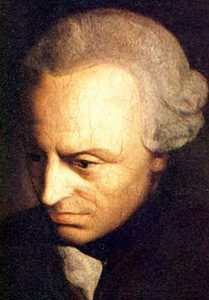

Figure 6-1: "Immanuel Kant" Source Permission: Public Domain.

In the past couple of modules, we have looked at some different means to determine whether a policy or action can be considered ‘just’. In our discussion, we introduced the consequentialist perspective of Utilitarianism. Bentham and Mill sought and defended a secular means to adjudicate the ethics of a policy or action via welfare or happiness. This was contrasted with Libertarianism which disagreed with the argument that it is the outcome that matters. For Libertarians, it is respect for individual rights and the defence of absolute self-ownership that determines if a policy or action is just. Next, we looked at the idea of the free-market and its claim on promoting justice, including its link to both Utilitarianism and Libertarianism. In this module, we turn to Immanuel Kant. In dealing with Kant, we are switching gears a bit. Kant isn’t speaking directly to the issue of justice; however, his work will become the basis for others that do. Kant is asking the question: what gives an act moral worth?

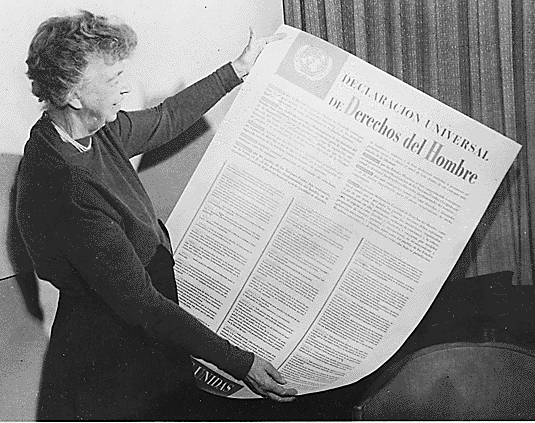

In attempting to answer that question, he examines the concepts of freedom, duty, human dignity, universality, and the capacity to reason. In the end, and through some very stringent conditions for each of these concepts, he arrives at an ethical test called the categorical imperative. Kant argues for the application of this test to all of our actions, even if (or especially when) such action goes against our self-interest. He believes this could lead one to a righteous life. Further, Kant argues that this test is universal to all people and in all places because it is derived from the human capacity to reason. This makes it possible to discover a universal law of morality. It is the process by which Kant arrives at this conclusion that will be the focus of this module. And while Kant is not speaking primarily about justice, his position on the categorical imperative has had a strong influence on important contemporary debates on human dignity and value as well as the implications of this in our increasingly globalized world. We can see this in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the debates around the treatment of refugees, and global climate change amongst many other contemporary issues.

Figure 6-3: "Eleanor Roosevelt with the UNDHR" Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Eleanor Roosevelt with the UNDHR.

Moreover, we will see in the next module the influence of Kant on a more contemporary political philosopher, John Rawls. However, we will also see that there are some problems with the application of Kant’s categorical imperative. The most common critique is that it is too rigid and too difficult to implement. That it is black and white, without the ‘grey area’ that typifies the real world. The universality of Kant’s categorical imperative is also critiqued as being potentially problematic. In order to explore the thoughts of Kant and its application to our discussion on justice, this module we will first look at Kant’s ideas on morality and freedom. This will be followed by his argument for the categorical imperative. Finally, we will close with a discussion of Kant’s thoughts on justice.

When you have finished this module, you should be able to do the following:

- Discuss Kant’s ideas of morality and freedom

- Apply the concepts of morality and freedom to Kant’s categorical imperative

- Debate the meaning of the categorical imperative to the concept of justice

- Read Chapter 5 in Michael Sandel’s Justice

- Take the Quiz “Are you a Kantian or a Utilitarian? https://www.proprofs.com/quiz-school/story.php?title=are-you-a-kantian-or-utilitarian

- Post your Quiz Results on the Live Poll App

- Watch the video “Are your actions good? (Kant vs Mill) – 8 bit Philosophy” https://youtu.be/Ngp1Qd8D2PQ

- Read “Germany Scraps Plane Shoot-Down Law” https://www.cbsnews.com/news/germany-scraps-plane-shoot-down-law/

- Complete Learning Activity #2

- Watch Mark Woolman’s “The categorical imperative” https://youtu.be/c_a00tW61I0

- Watch the BBC Radio 4 video “Kant’s Axe” https://youtu.be/x_uUEaeqFog

- Complete Learning Activity #3

- Watch “Climate Deal in Paris: Everything you need to know” https://youtu.be/qdqPoX9IV9A

- Read “Philosophy and climate: Kant at Le Bourget” https://www.thelocal.de/20151208/kant-at-le-bourget-philosophy-and-the-climate

- Complete Learning Activity #4

- Categorical imperative

- Duty

- Emotivism

- Ends

- First principles

- Freedom

- Human dignity

- ‘Humean’ problem

- Hypothetical imperative

- Kingdom of Ends

- Means

- Morality

- Reason

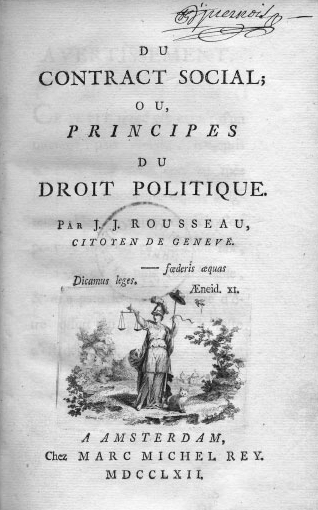

- Social Contract

- Supreme principal of morality

- The first formulation of the categorical imperative

- The second formulation of the categorical imperative

- The third formulation of the categorical imperative

- Universality

Read Chapter 5 in Michael Sandel’s Justice [Textbook]

Read “Germany Scraps Plane Shoot-Down Law” https://www.cbsnews.com/news/germany-scraps-plane-shoot-down-law/[Online]

Learning Material

Figure 6-4: “Kant and Friends at Table” Source Permission: Public Domain. Courtesy of Emil Doerstling.

However, Kant came to philosophy late in life and he only published the first of his influential works, Groundwork, at the age of 57. His earlier academic work included publications on astronomy, mathematics, and geology. So how did Kant come to be so foundational to political philosophy?

Figure 6-5: “David Hume” Source Permission: Public Domain.

Kant was motivated by the work of David Hume, stating Hume’s work had woke him from his ‘dogmatic slumbers’ and that his most influential work, the Critique of Pure Reason, was the solution to the ‘Humean problem’ of scepticism towards inductive reasoning. Hume’s scepticism of inductive reasoning influenced his position on morality and can be seen in his promotion of an early form of ‘emotivism’ which argues we cannot know objective moral facts but only our reaction to situations. This means that moral statements are really statements about our personal reaction to situations. Kant struggled with Hume’s sentimentalism, and as he sought an answer to the question of what gives an act moral worth, he moved further and further away from Hume’s position.

However, in order to facilitate an easier discussion of this tension, let us move from Hume to someone we have already discussed and who built on Hume’s ideas: Jeremy Bentham. To review: Bentham’s Utilitarianism is consequentialist, determining whether an action or policy is good, moral, or just based on its outcomes. If an action or policy produces the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number of people, it is good, moral, and just. Kant, on the other hand, sought to discover the supreme principal of morality and believed that it could be found through reason.

Hence his reaction to Hume! He did not argue that humans do not feel pleasure and pain, but he does deny Bentham’s assertion that pleasure and pain are our sovereign masters. Instead, he posits that humans are not merely animals; we are not necessarily slaves to our desires. Humans are rational beings with the capacity to use reason and therefore have the capacity to act and to choose freely. Kant thus argues reason can be our sovereign master and that with its application we can discover moral law. In the process of doing so, Kant also stakes some pretty strong claims on individual rights. He argues, as rational beings, every individual is worthy of dignity and respect. Every individual deserves to be treated not as an object, nor as a means to some end that another wants. Rather, every individual, in having absolute value, deserves to be treated as an end in and of themselves. As we will see in the final section, this has some important implications for universal human rights. But how do we get from Kant’s view of humanity to answer the question of what gives an act moral worth? To get that answer, we need to look at two pieces of the puzzle. First, we will look at Kant’s view of freedom and morality. We will then look at his argument on the categorical imperative. Using these two sections, we will conclude with a brief look at Kant’s take on justice.

- Before moving on, let us assess if you are a Kantian or a Utilitarian.

- Take the Quiz https://www.proprofs.com/quiz-school/story.php?title=are-you-a-kantian-or-utilitarian

- On the live poll app post whether you are a Kantian, Utilitarian, or Kantarian.

For Kant, freedom is by definition the opposite of necessity. Freedom is to act autonomously. Autonomy is the capacity to deliberate, to reason, to choose freely without compulsion. If I am driven to act by the laws of nature, feel compelled to act by social norms, or even seek pleasure/avoid pain, I am not acting autonomously, I am not acting freely. Rather I am acting on inclination and Kant calls this heteronomy. He defines this is the opposite of autonomy. When I am acting according to heteronomy, I am choosing a means to a given end. I am choosing to eat a steak in order to satiate my hunger. I am choosing to not smoke in a restaurant in order to avoid social approbation. I am choosing to use another human being in order to feel pleasure. I am choosing to not run a marathon to avoid pain. In all of these examples, I am choosing a means to an end. In contrast, Kant argues autonomy is to act according to a law I give myself; to choose the end itself and for its own sake. And this is something he believes that only a rational being can do, only a human can do.

By linking freedom to human will, we see Kant beginning to pivot to morality. When acting autonomously, we are exercising our capacity for reason. Our capacity to reason sets us apart, and as such, indicates we are endowed with inherent worth and dignity. This inherent worth and dignity requires us to not treat ourselves nor others as simply means. We must treat ourselves and others as ends in and of ourselves. This is Kant’s critique of Utilitarianism. Utilitarianism is ok with any means as long as the ends increase happiness. If we must sacrifice the Christians to the lions to maximize societal happiness, so be it. The ends justify the means. But if each individual has inherent worth and is an end in and of themselves, it is impermissible to treat them as a means for the general happiness. We must respect human dignity. Further, it is the treatment that gives moral worth, not the consequences. It is not the consequences of sacrificing the Christians to the lions that needs to be assessed to determine its morality but the treatment of the Christians themselves, the motivation to sacrifice them. For Kant, moral worth is determined by motive, by intention, by the quality of the will. This requires not only doing the right thing but to do the right thing for the right reason.

Figure 6-9: “Master Cheng Yen Start with good intentions and one will head in the right direction” Source Permission: CC BY-SA 2.0 Courtesy of BK.

Take John Stuart Mill for example. Contrary to Bentham’s logic, Mill might decide to not sacrifice the Christian to the lions because in so doing he would be violating higher pleasures and reducing aggregate happiness. But according to Kant, he is still not acting morally. He is not acting morally because he has the wrong intention. The right intention, the moral intention, is to treat the Christians as people with inherent worth, as an end in and of themselves. For Kant, it is important to not only conform to the moral law but to act for the sake of the moral law. So according to Kant, what makes an action morally good? In order to answer this question, it is important to note that Kant is not looking for an answer for him, or me, or you, individually. He is looking for an answer that applies to all rational human beings. He is looking for an answer grounded in first principles, a foundational position that cannot be deduced from another assumption. For Kant, the foundational principle of morality can be found through human reason. He argues that a moral act requires a good will, a good intention, a good motive. And that a person’s will is only good when they are motivated by duty. Kant contrasts duty with inclination. To act on inclination is to act on appetites, on natural laws. It is to choose a means to an end not determined by us. When we act from duty, we are willing the right thing out of respect for ourselves as rational law giving beings. It may even require doing so when it is against our self-interest. And in such cases, we clearly see the necessity of autonomy in acting morally. Here we see freedom and morality come together for Kant.

Watch the video “Are your actions good? (Kant vs Mill) – 8 bit Philosophy”

Read “Germany Scraps Plane Shoot-Down Law” https://www.cbsnews.com/news/germany-scraps-plane-shoot-down-law/

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What is the difference between Kant and Mill on determining the moral worth of an action?

- How does Kant define duty?

- How does Mill see pleasure?

- What are the implications of each position on morality?

- In Germany, the courts struck down a law that would allow the government to shoot down a hijacked airliner

- The argument was made that the law was “incompatible with the fundamental right to life and with the guarantee of human dignity”

- What would Kant and Mill say about this decision?

- Which position do you find most convincing and why?

For Kant, this answers the first question on the possible subjectivity of morality. These ideas are further developed in Kant’s idea of the categorical imperative. He argues that there are two types of reason: instrumental reason and pure practical reason. Each type commands the human will differently. Instrumental reason leads to a hypothetical imperative: if you want X you must do Y. It is a conditional imperative since Y is only produced on condition of doing X. For example, if I have no money but am in dire need of it, I must lie to my friend to get it. Pure practical reason leads to a categorical imperative: do Y because it is a good in and of itself. It is an unconditional imperative. For example, I tell the truth because it is the right thing to do. Kant argues only a categorical imperative can be an imperative of morality.

Figure 6-11: “Morals” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Courtesy of arnoKath.

In his writing, Kant gives several formulations of the categorical imperative, but we are going to look a two here which build on the arguments introduced so far. The third formulation will be discussed in the next section. The first formulation of the categorical imperative: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”.

When Kant says ‘maxim’, he means a fundamental rule or principal. So if we take a principle of action and universalize it, is it sustainable? For example, is it morally permissible to lie? Is it morally permissible to lie in dire need? To test this position, we should universalize the maxim of telling a lie. If everyone lies, truth would become unknowable and lies would no longer serve a purpose. The universalization of the maxim would render the act of telling a lie meaningless and unsustainable. It therefore fails the test. The second formulation of the categorical imperative: “Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end.”

Remember, Kant is looking for a supreme principal of morality, a universal understanding of morality. This means we cannot base moral law on particular people and circumstances. So what can we base moral law on? Kant believes that humanity, as constituted by rational beings, has absolute value. Therefore, we can not treat a person as a relative value, as a means to achieve our particularistic ends. Everyone has the capacity to reason, and therefore is due dignity. Consequently, we must respect people universally, we must treat people as ends in and of themselves. Let us apply this to our example of telling a lie in dire need. This failed the test of the first formulation of the categorical imperative, how about the second? If we tell a lie to advance our own interests, we are using others as a means to do so. We have not respected their humanity, their dignity. We have put our interests above others. Telling a lie, even in dire need, thus fails the second formulation of the categorical imperative. If we put these two formulations of the categorical imperative together, we see that according to Kant, an act is only moral if it can be universalized and if we treat humanity as ends.

Watch Mark Woolman’s “The categorical imperative”

Watch the BBC Radio 4 video “Kant’s Axe”

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal:

- What is the categorical imperative?

- How does it relate to reason and duty?

- What does Kant suggest you do if a dodgy person shows up at your house looking for your friend?

- Should you lie and protect your friend?

- Should you tell the truth even if that may endanger your friend?

- According to Kant, what are the moral implications of each position?

- How does this shed light on the categorical imperative?

- Is Kant’s idea of the categorical imperative too demanding?

- What would you do in the case of Kant’s Axe? Why?

It should not privilege particular groups, particularly constitutionally, over others as this would fail to respect the right of individuals to pursue their own ends. It would be based on particularistic notions of happiness, welfare, and justice. On the other hand, Kant is seeking a universal constitutional framework which creates space for, and mitigates tension between, individual freedom. For this reason, Kant introduces an interesting take on the social contract. A social contract is some form of agreement between members of a political community, where most often some trade-offs between individual freedom and governmental protection are agreed to. It is a statement of reciprocal rights and obligations between citizens and the state.

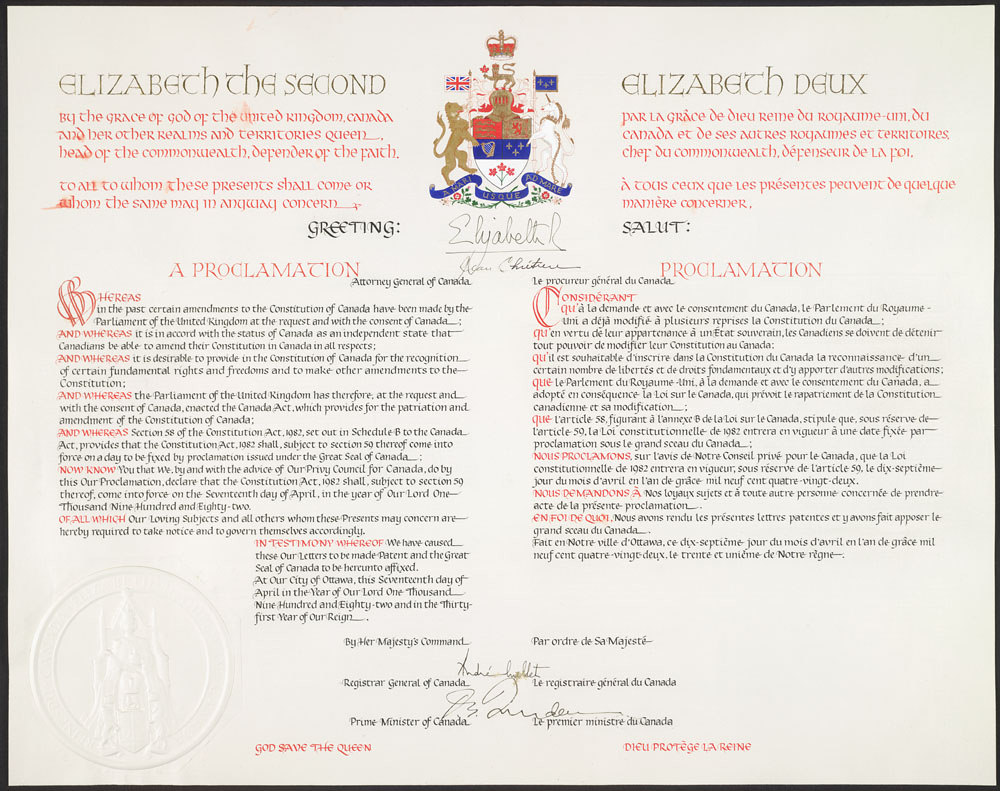

This idea of the social contract is closely associated with Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Kant’s social contract is a bit different. The above authors generally conceive of such a contract as having been negotiated and agreed to by real people; between citizens and state representatives. For Kant, this is neither practical nor welcomed. In terms of practicality, think of Canada. Who agreed to our constitutional arrangements? Was it ‘the Founding Fathers’ in 1867? The British North America Act was more a rule sheet for a British Dominion. Was it via the Treaty of Westminster in 1931 whereby sovereignty more fully came to rest in Ottawa? Or was it not until 1982 and the patriation of the Constitution by the Liberal Government of Pierre Trudeau?

Figure 6-15: “Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada / Bibliothèque et Archives Canada.

Figure 6-16: “San Marino” Source Permission: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Courtesy of Rajesh Pamnani.

And whatever date/person you pick, why should we be obligated to their vision of the ‘good life’? Now, try a similar exercise for San Marino, a city state in Italy that has been independent since 301 AD. However, more importantly for Kant, the moral principles which underpin such constitutional arrangements cannot legitimately be based on the desires of individuals or even communities. A moral and just constitution can only be based on an ‘idea’ of reason, whereby every piece of legislation should be framed so as to be logically consistent with ‘the united will of a whole nation’. He calls this the idea of collective consent. Just as he sought universality in conceptualizing the supreme principal of morality, Kant sought universality in the social contract and believed this discoverable through reason. We can get a glimpse of what Kant meant by this through his third formulation of the categorical imperative: the Kingdom of Ends. (Sometimes also called the Realm of Ends) This third formulation of the categorical imperative states: ‘all maxims as proceeding from our own lawmaking ought to harmonize with a possible realm of ends as a realm of nature.’ This formulation of the categorical imperative again stresses the autonomy of the individual, demanding that we regard ourselves as law-giving. It has been suggested that Kant is reacting to Rousseau’s ideal society whereby each citizen is both sovereign and subject; whereby each citizen is both the source of law and subject to the law.

Figure 6-17: “Social contract” Source Permission: Public Domain.

For Kant, this third formulation of the categorical imperative means that we must think of the political community as being collectively constituted by rational human beings. That in this political community, we must be governed by laws that all could arrive at because of our universal capability for reason. This links Kant’s idea of autonomy to acting collectively in society. It also suggests an interesting thought experiment. What would a kingdom of ends look like? If all members of the community both personally abide by the first two formulations of the categorical imperative and use these formulations in drafting legislation, what would it look like? Where all actions are based on universalizable principles. Where all actions treat are fellow members as worthy ends in and of themselves. These are goals and limitations which we autonomously seek and impose on ourselves. Kant believes this would constitute a righteous society. Now consider the limitations of that political community? Since Kant believes it is based on the universal capability of all human beings to reason, there is no political limitation to the community. This raises the question, according to Kant, what are our obligations to others in the global community? When discussing both the moral basis and practicality of world peace, or as he states Perpetual Peace, Kant posits the ultimate moral community is co-terminus with the world community; it includes everyone. He argues the ideal political order would be a federation or league of nations with each upholding the third formulation of the categorical imperative. Thus, we can infer that for Kant, justice is connected to the supreme principal of morality and based on both personal and collective action that observed the categorical imperative.

Watch “Climate Deal in Paris: Everything you need to know”

Read “Philosophy and climate: Kant at Le Bourget” https://www.thelocal.de/20151208/kant-at-le-bourget-philosophy-and-the-climate

Use the following questions to guide an entry in your Journal

- What was the Paris Climate Summit?

- What was in the Paris Climate Agreement?

- How does Kant see the problem of giving free rein to our autonomy in the world?

- What would climate justice look like to Kant?

- Use the idea of ecological footprints, apply the categorical imperative to climate change?

- You can read about ecological footprints and the per capita ranking of countries here: http://climatepositions.com/ecological-footprint-updates-2014-152-countries/

- Do you think Kant provides helpful insight into tackling issues like climate change?

This module has sought to introduce the ideas of Immanuel Kant and explore their applicability to issues of justice. Kant is not an easy thinker to get a grasp on. Part of this is due to the black and white nature of his writing. Such firm positions make it seem untenable in a world that is seemingly shrouded in shades of grey. Part of this is due to the goal of his writing. Kant is responding to the emotivism of his time. He is trying to discover and elucidate first principles in order to define the supreme principal of morality. That being said, it is worth struggling with. Kant is one of the most influential enlightenment thinkers and is foundational to modern political philosophy. In this module, we looked at his ideas in relation to justice. Much of Kant’s work sought to discover the supreme principal of morality. In reaction to many of his contemporaries who looked to human emotion and a utilitarian logic of pain and pleasure as sovereign masters, Kant sought a more universal answer. He believed that such an answer could be found in the universal human capacity of reason. Kant posits that humans are not merely animals; we are not necessarily slaves to our desires. Humans are rational beings with the capacity to use reason and therefore have the capacity to act and to choose freely. tO rise above our animal desires. Kant thus argues reason can be our sovereign master and that with its application we can discover moral law as defined by duty. Perhaps the most important of Kant’s conclusions is the categorical imperative. Through the three formulations of the categorical imperative that we looked at, Kant argues that to live a righteous life in a righteous society: we must universalize the maxims of our action; we must always treat our fellow humans as ends and never as means; we must apply these processes when drafting the laws applicable to all citizens. But Kant is also critiqued. His definitions are very stringent. His views are very rigid, very black and white. Think of the thought experiment of Kant’s Ax. Kant argued you can not lie, even if in so doing you may think you are protecting a significant other from a man standing at the door with an ax. He argues that if you lie and harm still comes to your significant other, you would be morally responsible. If you tell the truth, you are not morally responsible even if harm occurs because you are responsible for your intentions not outcomes. Finally, while Kant is not directly speaking to the issue of justice, his insight on living a righteous life gives us much to consider. It also gave others much to consider, such as John Rawls who will be introduced in the next module.

Review Questions and Answers

Glossary

Categorical imperative: is the moral obligation that applies unconditionally to all actors and does not depend on any ulterior motive or end.

Duty: is a moral or legal obligation to perform a responsibility, task or action.

Emotivism: is the argument that we cannot know objective moral facts but only our reaction to situations, therefore, moral statements are really statements about our personal reaction to situations.

Ends: is an inherent value that is not dependent on anything else. It is the goal or objective.

First principles: are a foundational position that cannot be deduced from another assumption.

Freedom: is the condition or state of being at liberty to do what one wants.

Human dignity: is the inherent value or worth of every human.

‘Humean’ problem: also refers to the problem of induction. It is the problem of inductively inferring that the future will resemble the past, the unobserved will imitate the observed.

Hypothetical imperative: is a conditional command that applies in virtue of having a rational will, but not simply in virtue of this.

Kingdom of Ends: a postulated political community where all citizens live by the categorical imperative

Means: is the avenue to pursue a certain goal.

Morality: is the belief, principle or standard that certain behavior is good and acceptable and others are not.

Reason: is the cause or justification to explain something.

Social Contract: is some form of agreement between members of a political community, where most often some trade-offs between individual freedom and governmental protection are agreed to

Supreme principal of morality: is Kant’s Categorical Imperative to act objectively, unconditionally, and rationally necessary despite the natural desires or inclinations to act contrary.

The first formulation of the categorical imperative: states “act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”.

The second formulation of the categorical imperative: states “act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end”.

The Third Formulation of the Categorical Imperative: ‘all maxims as proceeding from our own lawmaking ought to harmonize with a possible realm of ends as a realm of nature.’

Universality: means that it is true or factual for all similarly situated individuals.

References

Alfano, Sean. “Germany Scraps Plane Shoot-Down Law.” CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/germany-scraps-plane-shoot-down-law/

Blackburn, Simon. 2008. “Kant, Immanuel.” The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, 2nd Ed. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.cyber.usask.ca/view/10.1093/acref/9780199541430.001.0001/acref-9780199541430-e-1744?rskey=Az0TdJ&result=1745

Blackburn, Simon. 2008. “respect for persons.” The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, 2nd Ed. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.cyber.usask.ca/view/10.1093/acref/9780199541430.001.0001/acref-9780199541430-e-2705?rskey=xF3TrO&result=10

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. n.d. Categorical imperative. Accessed June 09, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/topic/categorical-imperative.

Burgess-Jackson, Keith. 2017. “Understanding Kant’s Categorical Imperative.” University of Texas Arlington. https://www.uta.edu/philosophy/faculty/burgess-jackson/Understanding%20Kant's%20Categorical%20Imperative.pdf

“David Hume.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Revised May 2014.https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hume/

Dictionary, Collins. n.d. Morality. Accessed June 09, 2018. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/morality.

Duignan, Brian. n.d. Problem of Induction. Accessed June 09, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/topic/problem-of-induction

Honderich, Ted (Ed). 2005. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usask/reader.action?docID=422618&query

Johnson, Robert, and Adam Cureton. 2001. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. February 23. Accessed June 09, 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-moral/.

“Kant and Hume on Causality.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Revised December 2013.https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-hume-causality/

“Kant and Hume on Morality.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Revised March 2018. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-hume-morality/

“Kant’s Moral Philosophy.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Revised July 2016. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-moral/

Kemerling, Garth. 2011. Philosophical Dictionary: Ubermensch-Utilitarianism. December 31. Accessed June 09, 2018. http://www.philosophypages.com/dy/u.htm.

“Moral Sentimentalism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. January 2014. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-sentimentalism/

Motilal, Shashi, Divya Juyal. 2016. “Human Rights and Public Policy Frameworks: A Kantian Perspective.” Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research 33(2):.241-251.

“Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” United Nations. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/UDHR/Documents/UDHR_Translations/eng.pdf

“Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” United Nations. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html

Velasquez, Manuel, Claire Andre, Thomas Shanks, S.J., and Michael J. Meyer. 2014. “Rights.” Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. https://www.scu.edu/ethics/ethics-resources/ethical-decision-making/rights/

Supplementary Resources

- Attfield, Robin. Ethics of the Global Environment. 2nd ed. Edinburgh Studies in Global Ethics. 2015.

- Bruce, Michael. "Categorical Imperative as the Source for Morality." In Just the Arguments, 217-20. Oxford, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell, 2011.

- O'Shea, James R. Kant's Critique of Pure Reason: A Critical Guide. Cambridge Critical Guides. 2017.

- 2009. “Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 06: ‘Mind your Motive” Harvard university, 55:14, a lecture by Michael Sandel published on 9 Sept 2009. Accessed June 5th https://youtu.be/8rv-4aUbZxQ

- 2009. “Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 07: “A Lesson in Lying” Harvard university, 55:05, a lecture by Michael Sandel published on 9 Sept 2009. Accessed June 6th https://youtu.be/KqzW0eHzDSQ